Partners Martin MacLean and Anna Gregson have been featured in ‘Global vaccine patents rise, as data reveals shift in Big Pharma strategy’ in LSIPR, ‘Global vaccine patents up 7% in a year despite US government’s stance’ in Manufacturing Chemist and ‘Vaccine patent applications hit record high, new data reveals’ in Drug Discovery World.

In the articles, Martin and Anna provide commentary on how, despite anti-vaccine rhetoric stemming from parts of the new US administration, the number of vaccine patent applications being filed are still rising steadily after the post-COVID spike, highlighting that traditional vaccine technologies are making way for safer methods following the success of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine.

Read the extended press release below.

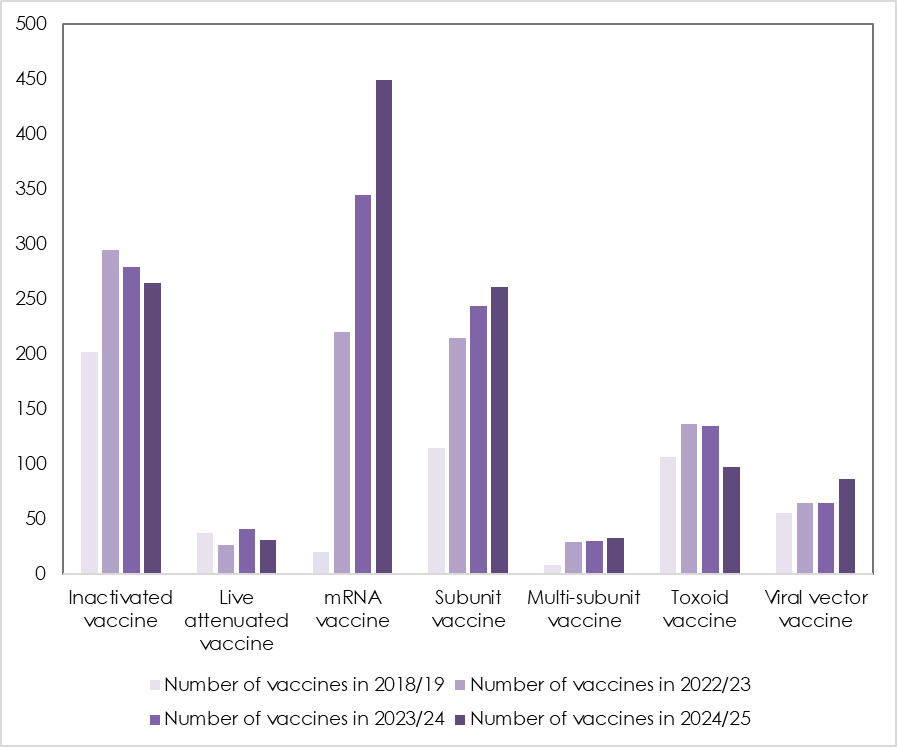

Global vaccine patents applications grew by 7% in the year to June 2025, rising to 1220 from 1135 the previous year, says intellectual property (IP) law firm Mathys & Squire.

Vaccine patent applications increased sharply after the COVID pandemic with 15% growth recorded in 2023/24, when patents applications increased from 983 to 1,135. Even so, the volume of applications is still up 129% compared with 2018/19, when there were just 542.

What is interesting to note is the very clear shift in vaccine strategy that has been adopted by pharmaceutical companies, and in such a short period of time. Traditional vaccine technologies such as toxoid vaccines and attenuated vaccines are being replaced by safer, more agile technologies such as mRNA vaccines.

Patent applications for RNA vaccines now dominate the evolving patent thicket, increasing 31% to 449 in 2024/25, up from 344 the previous year and only 20 in the year 2018/19. RNA vaccines deliver a small immune triggering part of the virus directly into a cell.

Mathys & Squire says vaccine technology is moving away from traditional vaccines to more advanced technologies like DNA and RNA vaccines. Traditional vaccines include ‘toxoid’ vaccine types, which use inactive toxins to prompt an immune response, like the tetanus vaccine, and subunit vaccines use proteins to trigger an immune response.

Consistent with this shift to new technologies, toxoid vaccines saw the sharpest drop in patent applications, with filings down 28% to 97 in 2024/25, from 134 the previous year. Inactivated vaccines saw a 5% drop to 264, from 279 in 2023/24.

Mathys & Squire says the success of the Covid mRNA vaccine shows that using these newer, more agile technologies can deliver effective protection at a lower cost than conventional vaccines. There are also significant safety benefits to the newer technologies.

Traditional vaccines, such as live attenuated vaccines or toxoid vaccines often require the culture of large quantities of the microbes. This requires expensive equipment and reagents and can be associated with safety and containment concerns.

On the other hand, the genetic material used in RNA vaccines is comparatively cheap and easy to produce. Additionally, since RNA vaccines do not contain a pathogen (either active or inactive) they are not infectious, making them safer for patients, clinicians and those involved in their manufacture, says Martin MacLean, Partner at Mathys & Squire.

Anti-vaccine comments from parts of the new US administration may further slow development of vaccines.

Mathys & Squire warns that recent anti-vaccine comments from some US Government officials risks adding to a slowdown in vaccine R&D.

Martin MacLean says: “Vaccine development is an expensive process. Mixed messaging from the Government could deter new investment – and therefore limit the number of new vaccines that can be developed and patented.”

RNA patents boom, and are now the largest number of new patent filings.

* Year end 30 June 2024. Figures are based on international vaccine patent applications published under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) during the 12 months to June 2019, 2023, 2024 and 2025, classified by type: inactivated (264), live attenuated (31), mRNA (449), subunit (261), multi-subunit (32), toxoid (97), viral vector (86).

Managing Associate Richard Jaszek has been featured in WIPR (World Intellectual Property Review) with his article, ‘Is the UK’s £16bn space industry being held back by out-of-date patent law?’

The article highlights how the rapidly advancing innovation in the space sector requires a robust intellectual property framework, the existence of which is ambiguous on account of the territoriality of patent law. According to Richard Jaszek, the UK is at risk of falling behind within the space-tech industry and it’s time to consider whether the nature of our patent law plays a part.

Read the article in full here.

Partner Harry Rowe and Trainee Trade Mark Attorney Tanya Rahman have been featured in Practical Law with their article, ‘Trade mark genuine use: “use it or lose it” Brexit deadline’.

In the article, they highlight the revocation risk for UK and EU trade marks following the upcoming deadline of 31 December 2025, providing vital guidance for reviewing trade mark portfolios, collating evidence of genuine use of trade mark registrations, to mitigate the risk of loss of rights.

This article first appeared in the October 2025 edition of PLC Magazine.

Trade mark genuine use: “use it or lose it” Brexit deadline

Both UK trade marks and EU trade marks (EUTMs) become vulnerable to applications for revocation on the ground of non-use unless they have been put to genuine use for a continuous period of five years in the territory in which they were registered. Before Brexit, this requirement would be fulfilled for EUTMs by their use anywhere in the EU. After 11pm on 31 December 2020, known as IP completion day, any use in the UK of a EUTM, or a UK trade mark that was automatically “cloned” from an EUTM, does not count as use in the EU and, equally, any use in the EU does not count as use in the UK.

This situation has created an imminent revocation risk for trade mark owners, as the five-year period from IP completion day will conclude at 11pm on 31 December 2025. This will leave both UK- and EU-based businesses at risk of not being able to enforce their trade mark rights against third parties that use identical or similar marks in their relevant territories. It is imperative that businesses review their registered trade mark portfolios in advance of this upcoming deadline to mitigate the risk of revocation.

Genuine use

There are typically two instances in which a trade mark owner may need to provide evidence of genuine use of its trade mark registration:

- In response to a revocation action on the ground of non-use brought under section 46(1)(a) or 46(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (TMA), or Article 58(1)(a) of the EU Trade Mark Regulation (2017/1001/EU) (EUTM Regulation). This could be as a counterclaim to infringement.

- In response to a request under section 6A of the TMA or Article 47(2) of the EUTM Regulation for proof of use of a mark that was registered five years before the filing or priority date of an application that is being opposed on the basis of that earlier registration.

In order to constitute genuine use, the trade mark must have been used in the course of trade in respect of the specific goods or services covered by the registration.

Territories. The trade mark must have been used in a real, commercial way, in the territory in which the mark is registered; that is, within the UK for UK registrations and within the EU for EU registrations. It is not sufficient to use the trade mark in a minimal or token manner to seek to circumvent the risk of revocation.

For EUTM registrations, it is not necessary to demonstrate genuine use in every individual EU member state. What matters is that the use is sufficient to establish or maintain a real commercial presence within the relevant market. Therefore, commercially meaningful use in a single member state could be sufficient to qualify as genuine use across the entire EU.

Evidence of commercial use. There must be a clear and consistent chain of evidence demonstrating actual commercial use of the trade mark in connection with the specific goods or services covered by the registration (see box “Documenting genuine use”). However, genuine use is fact-specific and depends on the nature of the goods or services and the relevant market. In some cases, particularly where the goods or services are specialised, a short period of use or limited sales numbers may still constitute genuine use. The extent to which the mark has been used will be considered by reference to the market size of the relevant goods and services to determine whether that use was sufficient for the registrant to have acquired a market share.

Burden of proof. Where non-use is alleged, the burden is on the trade mark owner to demonstrate either genuine use of the trade mark or valid reasons for its non-use. These reasons must be due to exceptional circumstances that are beyond the owner’s control, such as delays caused by regulatory issues.

Variation of form. To best demonstrate the genuine use of a trade mark, it is recommended that the mark is used in the exact form in which it is registered. However, as brands evolve, updates to the visual presentation of a mark are common. Minor changes, such as modernising the design or refreshing the logo, may still be acceptable as long as they do not alter the overall distinctive character of the original registered trade mark. These variations can still constitute genuine use provided that the essential identity of the trade mark remains intact.

Earlier marks. The analysis of genuine use extends to all goods or services that are relied on in proceedings or are targeted by a revocation action. However, both the UK Intellectual Property Office and the EU Intellectual Property Office recognise that where a likelihood of confusion, or the continued validity of the registration, can be established based on only some of the earlier protected goods or services, it may be unnecessary to assess use across the entire specifications.

Subcategories. In practice, if genuine use is demonstrated for goods or services that are clearly identical or similar to those covered by the contested application, or where the revocation action only targets part of the specification, this may be sufficient to support the opposition or maintain the registration. However, evidence of use in respect of only a subcategory of a broader term, such as use in respect of video game software when the term “computer software” is covered, would likely lead to the registration only being considered to have been used for that particular subcategory.

Authorised third-party use. Use of the registered trade mark by a third party, with the owner’s consent, is deemed to constitute use by the owner. Importantly, this consent must have been given before the use took place. A common example of authorised third-party use is that made by licensees. Similarly, use by companies that are economically connected to the trade mark owner, such as subsidiaries or affiliates, may also qualify as genuine use, as long as the use is authorised. Where goods are manufactured by, or under the control of, the trade mark owner and then placed on the market by distributors, whether at wholesale or retail level, this is also generally recognised as genuine use of the registered mark.

Documenting genuine use

Failure to adequately document genuine use can leave registrations vulnerable to revocation. However, proving genuine use of a trade mark presents practical challenges, especially in gathering and organising sufficient evidence to satisfy legal requirements. Trade mark owners should:

- Compile a range of documents that demonstrate actual commercial and genuine use of the mark in connection with the registered goods or services. Suitable evidence may include sales invoices, marketing materials, packaging, labels, product catalogues and photographs showing the mark in use. Providing data on sales volume, turnover and market share further supports the commercial significance of the mark’s use, helping to establish that the use is genuine and not merely token.

- Maintain clear and consistent records over time. Trade mark owners should proactively gather and preserve robust evidence as the trade mark is used, because opposition or revocation deadlines often allow only a short timeframe to collect and file supporting documents, making last-minute evidence collection difficult.

- Analyse whether a trade mark has been used only in relation to some of the goods or services covered by the registration. If this is the case, the use of the trade mark may be insufficient to maintain the registration for the remaining goods or services, potentially leaving those parts of the registration at risk.

Post-Brexit cloning

Before Brexit, the scope of protection of an EUTM registration extended to the (then) 28 member states, including the UK. IP completion day marked the end of the 11-month Brexit transition period during which the UK remained subject to EU regulations. After IP completion day, EUTM registrations no longer offered protection in the UK. However, Article 54 of the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement allowed for EUTMs to become “comparable” UK trade marks.

To address this change, the Trade Marks (Amendment etc) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 (SI 2019/269) inserted a new section 52A and paragraph 1 of Schedule 2A into the TMA, which provided that EUTMs registered before 1 January 2021 would be treated as comparable UK registered trade marks from IP completion day; that is, they would be automatically “cloned”. These comparable UK trade marks maintained the same filing date, priority and seniority as the original EUTM registration, thereby preserving existing rights in the UK without requiring re-examination or refiling.

As a result, trade mark protection became split between the two jurisdictions, requiring efforts to separately maintain enforceable rights.

Genuine use after Brexit

Before Brexit, using an EUTM in the UK generally constituted genuine use of the EU registration. However, since IP completion day, the use of a comparable UK trade mark in the EU no longer qualifies as use of the UK registration. Likewise, only use within the EU now qualifies as genuine use of an EU registration. This means that:

- Comparable UK trade marks may face revocation after 31 December 2025 if they have not been genuinely used in the UK for the relevant goods or services over the preceding five years.

- Owners of comparable UK trade marks cannot rely on use within the EU in opposition proceedings filed after 31 December 2025; proof of use must relate solely to the UK.

Actions for businesses

Trade mark owners should review their trade mark portfolios ahead of the 31 December 2025 deadline and assess whether the use of their comparable UK trade marks and EUTMs still aligns with their current business strategy, and whether that use is likely to be considered to have been genuine.

It is essential that businesses carefully evaluate whether retaining the comparable UK registrations or EUTMs continues to be both necessary and suitable for their business, which involves assessing:

- The trade mark’s ongoing relevance to the brand strategy.

- The trade mark’s role in protecting key products or services.

- Whether the costs associated with maintaining the registration outweigh the benefits that it provides.

By conducting this review, owners can make informed decisions to optimise their trade mark portfolios. Where trade marks have not been used for certain goods or services in the UK or the EU, or if a business has rebranded and the trade mark is no longer used in a way that corresponds to the original registration, particularly where the change affects the distinctive character of the original mark, it may be advisable to file new trade mark applications. However, these filings should be managed carefully to avoid being perceived as “evergreening”, that is, submitted in bad faith solely to bypass the requirement to prove genuine use.

The Enlarged Board of Appeal has recently confirmed in G 2/24 that, after all appeals are withdrawn, appeal proceedings are terminated – even if an intervention is filed during the appeal. A party who intervenes only on appeal does not have the right to continue proceedings after the appeal is withdrawn.

The referring Board of Appeal in T 1286/23 sought clarification with the following question:

“After withdrawal of all appeals, may the proceedings be continued with a third party who intervened during the appeal proceedings? In particular, may the third party acquire an appellant status corresponding to the status of a person entitled to appeal within the meaning of Article 107, first sentence, EPC?”

Background – Interventions at the EPO

Under Article 105 EPC, a third party that is sued for patent infringement may intervene in EPO opposition proceedings – even after the normal 9 month opposition window – provided that the intervention is filed whilst opposition proceedings are pending (or a subsequent appeal is pending). This allows the third party to bring new objections and evidence into the opposition.

The Decision – G 2/24

The Enlarged Board considered the situation where an intervention was filed during appeal proceedings following opposition and then all appeals are withdrawn.

G 2/24 confirms an earlier decision in G 3/04, deciding that such an intervener could not then continue with the proceedings. The Board that referred the question in G 2/24 questioned this approach and indicated an intention to deviate from G 3/04. However, in G 2/24, the Enlarged Board concludes that the legal situation has not changed substantively since G 3/04 in respect of the relevant provisions, and that the conclusion given in that decision still applies.

The Enlarged Board confirms that an appeal is a judicial review of the decision under appeal and is not a mere continuation of opposition proceedings. The principle of party disposition is also reiterated, in that the party has the right to withdraw an appeal (and the Board itself has no right to continue). Under Article 107 EPC, an appeal can only be filed by a party to the original proceedings that is adversely affected by the decision.

This reasoning led the Enlarged Board to decide that the intervener did not have the status of appellant and did not have further rights beyond a non-appealing party in respect of continuing proceedings.

As a result, if the sole appeal is withdrawn (or, should there be multiple appellants, then if all appeals are withdrawn), an intervener that only files an intervention on appeal does not have the right to continue with the proceedings.

Strategic Implications

G 2/24 gives patent proprietors more control over appeal outcomes when they are the sole appellant. For example, if an intervention on appeal raises new issues, the proprietor may opt to withdraw the appeal if they are the sole appellant. With the appeal terminating, this may allow the proprietor to fall back on an amended form of the patent maintained after opposition.

From the intervener’s perspective, it may be more beneficial to intervene in opposition proceedings rather than only on appeal. Whilst the ability to intervene will be determined by the proprietor bringing infringement proceedings, the third party may pre-emptively file an opposition in the first place (which may be filed anonymously).

In any case, intervening on appeal may still be a useful tool. For example, this may force the proprietor to withdraw the appeal and limit the patent to narrower claims.

G 2/24 therefore provides legal certainty confirming that interveners on appeal cannot continue with appeal proceedings once all appeals are withdrawn. This has implications for strategic decision-making in both opposing and defending patents at the EPO.

If you have any questions about your opposition strategy, please contact a member of our team.

We are delighted to announce that Partners Edd Cavanna, Max Thoma and Harry Rowe have been named as 2025 Rising Stars.

The Managing IP Rising Stars guide recognises leading intellectual property practitioners across more than 50 jurisdictions and a wide range of IP practice areas. This prestigious list highlights professionals who are making significant contributions to the field and showing strong potential for future leadership in the industry.

Each year, Managing IP conducts extensive research to compile its rankings, drawing on feedback from IP practitioners, firms, and clients. The process includes detailed surveys, interviews, and an independent analysis of publicly available information, ensuring that the rankings are rigorous and impartial.

Managing IP identifies Rising Stars who have demonstrated exceptional work within their firms and in the broader IP landscape. Being named a Rising Star is a mark of recognition for consistent, high-quality performance and is considered a notable achievement.

For more information on the Mathys & Squire rankings, visit the IP Stars website here.

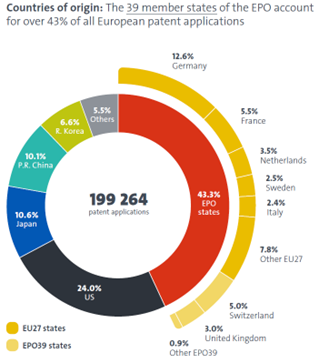

27.3% of all applications filed at the European Patent Office (EPO) in 2024 originated from China, Japan, and Korea. Almost all of such applications claim priority from patent applications filed locally in those countries, which are normally prepared and filed in the local languages. This means that the content of such applications must be translated into an EPO official language (normally English) either when a corresponding European patent application is filed or a PCT application enters the regional phase.

The intricacies of translation

Translation issues can invalidate patents in Europe. Priority claims are only valid if a priority document contains a clear and unambiguous disclosure of a claimed invention. This is a very strict test and minor differences in language can lead to allegations that a claimed invention was not disclosed in an earlier priority application.

Similarly, when a European patent application is derived from a PCT application, whether or not matter is added during prosecution is judged against the content of the original PCT application rather than the content of a translation filed on entry to the regional phase. Again, the EPO’s test for added matter is a strict one – did the original PCT application contain a clear and unambiguous disclosure of a claimed invention? Minor changes in language can result in a patent application failing such a test.

Whenever such issues arise, the EPO is forced to consider the content of documents written in languages other than the working languages of the office. When dealing with languages such as Chinese, Japanese and Korean which are far removed from the European languages with which the EPO is normally familiar, knowledge of how languages work and the quality of translations used can become crucial.

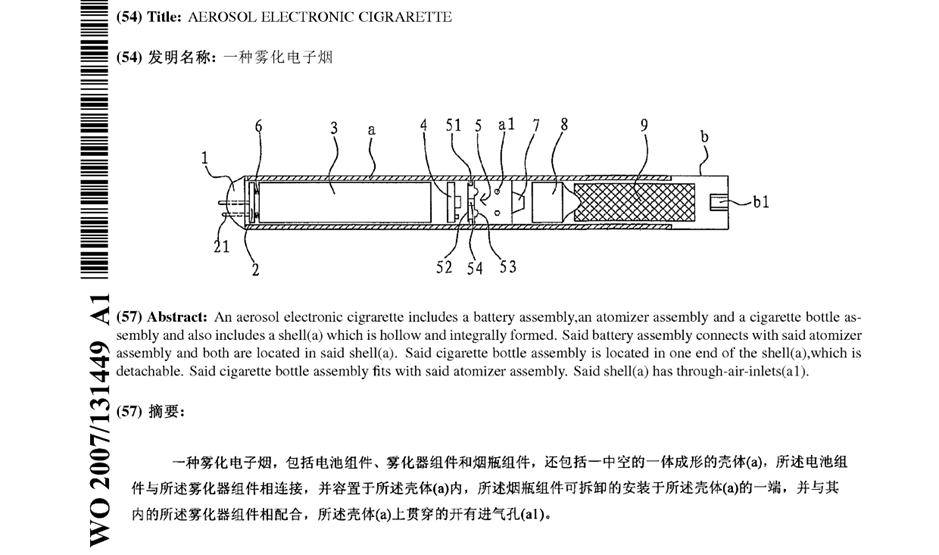

The Opposition against EP2022349

The Opposition against EP2022349, filed by seven Opponents, illustrates how unsatisfactory translations can jeopardise the validity of patents before the EPO.

EP2022349 relates to an early vaporiser design for electronic cigarettes. The patent was involved in litigation in the UK and Germany among various e-cigarette companies in the mid-2010s because it represents an early example of an e-cigarette patent which covered modern e-cigarette designs.

The patent was based on a PCT application WO2007131449, originally drafted in Chinese. Unfortunately, the Chinese text itself was less than satisfactory, and the English translation submitted on entry into the European phase was also of limited quality. This later led to numerous added matter issues under Article 123(2) EPC.

Translation issues and Added Matter disputes

Air Inlet(s)

The Opponents objected that the application did not disclose an electronic cigarette having a single air inlet. The patentee explained that the Chinese characters 进气孔used to refer to the air inlets in the original Chinese implicitly referred to “one or more air inlets” because in Chinese if a specific number of air inlets was to be intended this would need to be made explicit in the Chinese (e.g. 一个进气口 one air inlet or 两个进气孔 two air inlets).

“Perforated” vs “Porous”

The original translation rendered a key term 多孔 (“Duo Kong” two characters literally having separate meanings as “many” and “holes”) as “perforated,” later corrected to “porous.” The Opponents objected that this correction introduced added matter, a point that was upheld by the EPO in a related divisional case.

“Frame” vs “Support Member”

The Opponents objected that 架体 ( “Jia Ti” two characters literally having separate meanings as “frame” and “body”) had a restricted meaning of “frame” and that the translation of 架体 as “support member” added matter.

Conjunctions and Prepositions

Even small linguistic nuances triggered disputes. For example, the location of the air channel in the claim was objected to with an Opponent contending that the original Chinese referred to the air channel being located “in the centre on one end surface of a cigarette holder shell” rather than “in the centre of one end surface of a cigarette holder shell”. This objection was refuted by the patentee with an explanation that in the original Chinese it was clear the central air channel was located in the centre of the surface of the cigarette holder shell.

Resolution and practical lessons

Ultimately the EP Opposition against EP2022349 ended without a formal conclusion on these translation disputes, as the case was withdrawn prior to a final decision. Nevertheless, the case provides a valuable example of issues which can arise when an inaccurate translation is used as well as the manner in which such objections may be overcome – in this case affidavit evidence was filed to explain the differences between English and Chinese.

The EP2022349 Opposition is a cautionary tale for patentees, attorneys, and translators alike. Above all, it reinforces the importance of investing in precise translations and expert linguistic input at the earliest stages of international patent prosecution.

We are delighted to announce that Mathys & Squire has been commended in the 2026 edition of The Legal 500 in both PATMA: Patent Attorneys and PATMA: Trade Mark Attorneys categories.

Patent Partners Chris Hamer, Alan MacDougall, Martin MacLean, Paul Cozens, Andrea McShane, Dani Kramer, Philippa Griffin, James Wilding, Sean Leach, James Pitchford, Andrew White and Managing Associate Oliver Parish are all featured in the 2026 edition of the directory.

Mathys & Squire’s trade mark team also received recognition in the directory. From our trade mark practice, Partners Rebecca Tew and Harry Rowe, Gary Johnston, and Consultant Margaret Arnott have been featured in the 2026 edition.

The firm received glowing testimonials for its patent and trade mark practices:

‘The Mathys team is easy and a joy to work with. They have the experience and requisite background to digest complex scientific matters and undertake well-done patent prosecution. I quite enjoy strategizing together and our collaborative efforts. They are pleasant and appropriate in communications, as well as responsive.’

‘Dani Kramer is a pleasure to work with. He is sharp, provides excellent and cost-effective advice and professional services.’

‘I work with the team around partner Sean Leach, who is exceptionally responsive and technically highly competent, as is his team. Pleasant to work with, always transparent, flexible – highly recommended.’

‘Sean Leach is highly skilled technically, a great communicator, an excellent patent attorney, very experienced and very responsive.’

‘Paul Cozens as a standout partner, and Oliver Parish has impressive technical knowledge.’

‘Fantastic team work from an absolutely top-notch team.’

‘Very skilled and knowledgeable.’

‘They are absolutely committed to working with the customer. James Pitchford is outstanding with his knowledge and ability to apply it to IP writing.’

‘They have exceptional experience and expertise.’

‘They are a go to firm for EPO consultation.’

For full details of our rankings in The Legal 500 2026 guide, please click here.

We extend our gratitude to all our clients and connections who participated in the research, and we extend our congratulations to our individual attorneys who have earned rankings in this year’s guide.

Partner Nicholas Fox has been featured in an exclusive titled “Uptake of Unitary Patents Almost A Third of EU Total” in Law360 and “Report reveals unitary patent strategy of IT and engineering leaders” in the World Intellectual Property Review. This is following Mathys & Squire’s recent report, The Use of the Unitary Patent System in IT & Engineering by Partner Nicholas Fox and Associate Maxwell Haughey.

In these articles, Nicholas Fox offers deeper insights into why industry players within the field of IT & Engineering are becoming more open to the Unitary Patent system, whilst noting that some may still remain cautious on account of certain factors such as the likelihood of patent disputes and the cost of translation.

Read the extended press release below.

EU’s new unitary patents now account for 28% of all new patents granted – but major companies split on patent strategy

The EU’s new unitary patents (UPs) now account for 28% of all European patents granted in 2025 to date, up from 26% last year and 18% in 2023*, says leading intellectual property (IP) law firm Mathys & Squire LLP. Of the 19,000 European patents granted in 2024, 5,300 were maintained as UPs rather than as a bundle of national rights.

Mathys & Squire says that the Unitary Patent System, introduced in 2023, is cost-effective if the objective of patent proprietors is to obtain wide geographical protection in Europe. The cost of maintaining a Unitary Patent is roughly equivalent to the cost of maintaining patent protection in four European countries whilst giving inventors a single patent that applies to eighteen EU member states.

In some circumstances unitary patents can, however, be riskier than maintaining rights as a bundle of national patents. The primary risk is that a single court decision could see the patent revoked in all countries where it has effect.

According to Mathys & Squire’s Use of Unitary Patent System: IT & Engineering report, uptake of UPs varies significantly by technical field. The highest uptake of UPs is in civil engineering, where 39% of European patents granted in 2024 were maintained as UPs, up from 28% in 2023. Within the sectors sampled, the Defence sector had the lowest uptake with only 11% of defence patents granted in 2024 being maintained as UPs, that being an increase from 6% of patents granted in 2023.

Nicholas Fox, Partner at Mathys & Squire and European Patent Attorney, explains that uptake of UPs is typically lower in sectors requiring patents in only a few countries. The Oil and Gas sector is a good example of this. In many cases, oil and gas companies tend to only need patent protection only in the North Sea and hence often only in the UK and Norway. Such companies gain little from using UPs. Businesses in sectors needing broader geographical protection benefit more.

Says Fox: “In many sectors, Unitary patents are fast becoming one of Europe’s main patent types. They’re increasingly displacing the old ‘bundle’ system that requires separate validation in each country. They can be a cost-effective way of securing broad geographic protection for an invention in Europe. Adoption of unitary patents is, however, uneven across different technologies and amongst different companies even when companies operate in similar fields.”

Small businesses make proportionally greater use of unitary patents than large businesses

The slow uptake of UPs in some fields is partly due to translation requirements. In many IT and Engineering fields (e.g. telecoms), European Patents are typically maintained in countries where full translation isn’t needed, including the UK, Germany and France. Maintaining rights only in these countries can be sufficient for many companies operating in these fields.

The need for full translations to obtain a UP can be a significant factor behind the slow adoption rate of UPs in IT and Engineering. For companies with large portfolios, costs can mount up, as patents prosecuted in German or French must be translated into English, and those in English must be translated into any EU language.

This is backed up by research which finds that small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), who normally have far smaller patent portfolios are making greater use of the unitary patent than large businesses. SMEs accounted for just 23% of European patent filings in 2024 but obtained 36% of all UPs. Large businesses accounted for 69% of all European patent filings but only 57% of UPs. Universities and public research organisations account for the remainder of filings and UPs.

Fox says another reason for lower uptake among large businesses is uncertainty over the role of the new Unitary Patent Court (UPC). The UPC centralises patent disputes in a single court with authority across Europe. However, Fox says these concerns should ease as the court builds a track record of high-quality and predictable rulings.

Adds Fox: “Small businesses appear more enthusiastic about the new unitary patent system. The annual renewal fees to maintain multiple national patents account for a bigger share of their budgets than for large businesses.”

“Some large companies have taken a wait-and-see approach to the UPC. The UPC’s rulings have been consistent so far, giving businesses greater confidence in the system. We therefore expect large businesses to gradually increase their use of the unitary patent system.”

“Businesses are still weighing the costs and benefits of the new system. Broad European coverage can be attractive, but in fields with more frequent disputes, the risk of one court deciding everything across Europe is enough to make them hesitate.”

Leading businesses in tech and engineering take sharply different approaches

Mathys & Squire’s research shows significant variations in UP uptake in different sectors and between companies operating in the same sector.

In Automotive and Aerospace, Mercedes-Benz and Airbus have obtained UPs, while BMW, Boeing and Rolls-Royce have yet to meaningfully engage with the new system. Across the wider transport sector, UPs made up 21% of all European patents granted in 2024, up from 14% in 2023.

Similar variations are to be found within the Defence sector. Overall, engagement with the Unitary Patent system in the Defence sector has been limited with only 10% of European Patents in the sector granted in 2024 being maintained as UPs. Many Defence companies have either not engaged at all with the new UP system or have been highly selective in doing so. By way of example, only 6% and 3% of European patents granted in 2024 to Leonardo and Rheinmetal respectively were maintained as UPs. In contrast, BAE Systems chose to maintain 36% of their patents granted in 2024 as UPs and ThyssenKrupp chose to maintain all its European patents granted in 2024 as UPs.

In Digital Communications, UP uptake has also lagged, climbing from 11% in 2023 only to 18% in 2024. Ericson, and Samsung each converted large numbers of their European patents into Unitary Patents. But as with other areas of technology there is significant variation amongst the biggest filers. Some companies, like Lenovo, maintained all of their European patents granted in 2024 as unitary patents, while Google and Microsoft obtained no unitary patents and instead maintained their European patents as bundles of national rights.

The research also shows some large companies vary their level of engagement strategies across different technologies. For example, Qualcomm maintained roughly two-thirds of its semiconductor patents as UPs in 2024. But in the field of digital communications, the share of patents maintained by Qualcomm as UPs was only 30%.

* The 2023 figure shows the share of European patents that were filed as UPs since the regime came into effect

Mathys & Squire Partners Chris Hamer and Laura Clews, and Head of Consulting Lyle Ellis have been featured in “Patents on a Plate” by Protein Production Technology International (PPTI). They provided commentary on how to protect innovations and manage intellectual property in the alternative proteins industry.

The article in PPTI highlights how intellectual property is a crucial pillar of the industry, as innovation within protein production is evolving rapidly in response to growing consumer interest in sustainable and ethical food, from fermentation-based proteins to cell-cultured alternatives. Intellectual property assets, including patents, trade marks and trade secrets, are vital in preventing competitors from exploiting your innovation, but they also play a significant role in shaping how innovation develops.

Partners Chris Hamer and Laura Clews discuss how recent years have seen food companies demonstrating a greater recognition of the importance of IP, for example in attracting investors, as well as the necessity of a robust IP portfolio, spanning multiple jurisdictions, for start-ups in the industry. Head of Consulting Lyle Ellis touches on the tricky balance between maintaining exclusivity and ensuring that key technologies are accessible to others in the sector, evaluating the trade-off between patents and trade secrets.

You can read the full article here.

Partner Max Thoma has recently been featured in Law360 discussing the recent proposal by the UK Government to limit AI generated design applications in ‘Sweeping UK Reforms A Mixed Bag For Simplifying Designs’.

In the article, Max discusses how applicants have previously been able to apply for IP protection on design that have solely been created by AI. The new ruling would aim to prevent the UK design system becoming overwhelmed by a large number of applications, and ensure human-created designs do not have difficulty in being validly registered as a result.

Read the extended press release below.

The UK Government is proposing to change the law to prevent a flood of requests for the registration of completely AI generated designs says intellectual property (IP) law firm Mathys & Squire.

The proposal comes as part of a wide-ranging consultation launched by the Government on the intellectual property laws related to designs. Registering designs with the Intellectual Property Office can protect the appearance, shape or decoration of a product from being copied.

Unlike in other areas of intellectual property, UK design law contains provisions that allow protection for designs entirely generated by computer and without a human “author”.

Max Thoma, Partner, of intellectual property (IP) law firm Mathys & Squire comments: “The Government is worried by the possibility that the UK design system could be flooded with thousands of AI generated design applications. In theory AI tools churning out designs that are then registered could block new products from entering the market and make it more difficult for human-created designs to be validly registered.”

The consultation also proposes the introduction of an examination process for registered design applications in some circumstances. This would mean that some design applications will need to be reviewed and approved by the Intellectual Property Office.

Max Thoma says that this change is being proposed as some designs were being registered when they were invalid. In some cases businesses had been using those invalid design registrations to request the removal of a competitor’s product from online shopping sites.

There are number of other proposals in the consultation document including a proposal to make it easier to register animated designs.