Head of Trade Marks and Partner Claire Breheny has recently been featured in Law360 following the latest Court of Appeal decision between Adidas and Thom Browne in, ‘Adidas Ruling Offers A Warning For Brands On Position Marks’.

The IP dispute involves the sportswear brand and fashion designer brand Thom Browne, who had already brought Adidas to court in 2021 regarding the IP protection of their three stripe design. In the latest edition of the case, the Court of Appeal referenced EU case law to demonstrate that Adidas were not protecting a ‘single sign’, and consequently did not uphold their arguments.

In her commentary, Claire highlights the importance of detail when applying for, and managing, position marks, as evidenced through the case. The example also shows how the court will not overlook ambiguity, and can be treated as a lesson to those considering such IP protection.

To read the full article click here.

As this year’s Nobel laureate Omar Yaghi said, “science is the greatest equalising force in the world.” Yet many communities still face disparities in health, education, connectivity, and economic opportunity. STEM can help close these gaps through robust digital communications that keep people connected and enable rapid relief, voting technologies that make participation easier to trust, cleaner energy systems that use resources more efficiently, interactive tools that enrich learning and public spaces, and accessible health technologies that improve everyday communication and quality of life. With the above in mind, it is inspiring to spotlight black innovators whose patented ideas are already turning this promise of STEM into everyday progress.

Black History Month is as good a time as any to honour and celebrate some of the technical contributions of black people working in STEM to the world we live in, so in this article I explore some modern-day technologies developed by black people solving problems at the core of how we call, vote, hear and play.

Dr. Marian R. Croak

The telephone may have slain distance, but the internet now carries the burden of keeping us reliably connected, and Dr. Marian R. Croak’s work is central to that reliability. An important Voice over Internet Protocol invention, covered by patent US 7,599,359, addresses end-to-end performance monitoring in packet networks to keep calls intelligible under real-world conditions. Croak also helped facilitate small-donor philanthropy at scale with US 7,715,368 on text-to-donate, a mechanism that proved its value during disaster relief efforts in 2010. Taken together with a substantial wider portfolio, these patents form part of the infrastructure that underpins remote work, telehealth, and everyday family calls. [1], [2]

Dr. Lonnie G. Johnson

Dr. Lonnie G. Johnson’s inventive arc spans play and power. The Super Soaker (see US 5,074,437) redefined a consumer category through elegant pressure management. More recently, his Johnson Thermo-Electrochemical Converter (JTEC) filings, for example US 10,522,862, US 11,239,513, and US 11,799,116, relate to solid-state architectures that convert heat directly into electricity via membrane-electrode assemblies. The proposition is straightforward but significant: fewer moving parts, higher potential efficiency, and a route to harvesting industrial waste heat that could materially improve energy productivity. [3]

Lanny S. Smoot

In themed environments, the best engineering vanishes into the experience. Lanny S. Smoot’s portfolio exemplifies that principle. His retractable, internally illuminated“lightsabre” (US 10,065,127) pairs clever mechanics with controlled optics to create an effect that is both theatrical and robust. Across more than a hundred patents, Smoot’s work extends to sensing and interactive systems that allow venues to modulate content in response to guest behaviour, technology with clear applications beyond entertainment, including education and public exhibitions. [4]

Dr. Juan E. Gilbert

Trust in elections is built on processes that are easy to use and easy to audit. Juan E. Gilbert’s recent patents, US 11,334,295 for a transparent interactive interface for ballot marking and US 11,036,442 for a transparent interactive printing interface, are designed to make voter intent visible and verifiable at the point of selection. By allowing users to see exactly what is being printed as choices are made, these systems aim to reduce cognitive load, particularly for voters with disabilities, while strengthening paper-based audit trails. [5]

Prof. Fred McBagonluri

For custom hearing aids, small improvements in modelling and manufacture result in large gains in everyday usability. Prof. Fred McBagonluri’s co-invented filings, US 8,096,383 for tapered vents in ultra-small in-ear devices, US 8,135,153 for automatic wax-guard modelling, US 8,224,094 for left and right side detection of 3D ear impressions, and US 7,979,244 for aperture detection in hearing-aid shells, target pain points that historically caused feedback and user discomfort. The outcome is faster production, better fit, and more consistent acoustic performance. [6]

Summary

It is no secret that black people are underrepresented in STEM, which is why it is especially meaningful to me, as a black person with a STEM background, to see black inventors creating tools that work towards solving the problems above. As a patent attorney, it is even more meaningful to me to see those solutions protected by patents, because that recognition helps turn ideas into scalable innovations, attracts investment, and secures credit for the inventors shaping our future.

References

[1] Marian R. Croak – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marian_Croak_

[2] Brooks Kushman profile (Croak & Jackson): https://www.brookskushman.com/insights/black-history-month-dr-marian-croak-1955-and-dr-shirley-ann-jackson-1946/

[3] Lonnie G. Johnson – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lonnie_Johnson_%28inventor%29?

[4] Black Engineer profile (Lanny S. Smoot): https://www.blackengineer.com/imported_wordpress/1987-beya-winner-receives-100th-career-patent/

[5] Juan E. Gilbert – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_E._Gilbert

[6] Fred McBagonluri – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fred_McBagonluri?

We are delighted to announce that Partner Chris Hamer has been featured in the 2026 edition of IAM Global Leaders.

IAM Global Leaders 2026 celebrates some of the finest patent professionals in intellectual property, highlighting those that demonstrate an exceptional understanding of their specialism and the wider IP landscape, as well as consistent, high-quality work for their clients.

Those that have been chosen as IAM Global Leaders were featured in the IAM Patent 1000 2025 directory earlier this year as Recommended Individuals, in which Mathys & Squire were also ranked in the Gold tier as a firm.

IAM writes: “Chris Hamer is a diligent attorney, known for his timely and detailed advice. He has impressive expertise and know-how in the field, and he has navigated numerous challenging patent filings, ensuring crucial protection is achieved. His strategic approach is highly valued, empowering companies to make informed business decisions.”

To mark his recognition in the directory, Chris has featured in an online interview with IAM in which he shares his expert advice on IP strategy, patent portfolios, oppositions and appeals, and emerging technology within the industry.

Click here to read the full interview on the IAM website.

Is it cute or is it terrifying? No toy has ever caused such a divide in opinion. However, no matter what people think, the impact is the same: everyone has been talking about this mischievous-looking creature. The Labubu was officially the viral sensation of 2025.

Where did Labubu come from – and what now?

The origin of Labubu can be traced back to the mind of artist Kasing Lung, born in China and raised in The Netherlands. His illustrated book trilogy “The Monsters”, published in 2015, unveiled a whimsical world, shaped by his Chinese heritage and fascination with Nordic folklore, and brought various eccentric characters to life, including Labubu.

In 2019, Kasing Lung signed an exclusive licensing agreement with Pop Mart, giving the company commercial operation rights and the ability to transform Labubu from a toy to a powerful IP asset.

However, it was not until 7 years later, at the end of 2024, when the peculiar pet really started jumping into people’s shopping bags. Their scarcity is part of their appeal, with people going to great lengths to track them down, queuing for hours and paying hundreds of pounds for the addictive “blind box” experience. Social media is flooded with people flaunting their Labubus and special-edition Labubus are being sold at auctions for over $100,000.

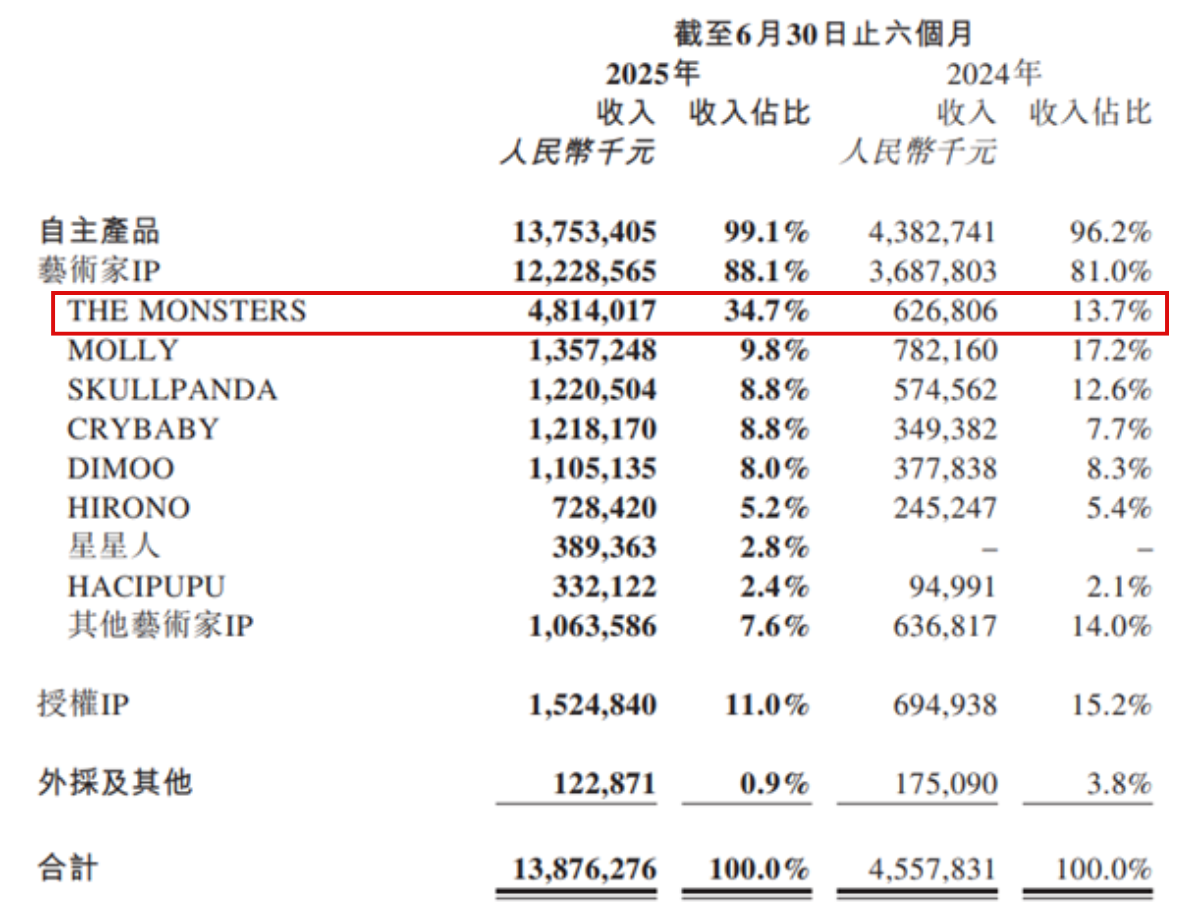

According to Pop Mart’s 2025 Interim Results Announcement, “The Monsters” generated an impressive 4.81 billion yuan (approximately $669.88 million) by 30 June 2025, making it Pop Mart’s most profitable IP.

Pop Mart’s IP strategy

In the toy industry, when products transcend their physical counterparts, becoming distinctive, memorable brands, IP plays a vital role. It allows a story or symbol to become a concrete entity which the owner can safeguard and profit from. With the IP safely in their pocket, Pop Mart was able to spread the Labubu figurines over the globe and watch the money flow in.

Pop Mart displays a robust, multi-layered approach to their IP, encompassing copyright, trade marks, and patents, demonstrating an understanding that design and branding are both highly valuable assets. By 2024, the company held over 1,200 trade marks, 1,600 copyrights and 45 patents.

Pop Mart’s patents mainly cover innovations in product functionality and production techniques, including toy assembly methods, and CNC water transfer printing and related equipment. Design patents, on the other hand, primarily protect the toy’s overall shape, facial expressions, and distinctive visual features such as unique clothing or accessory designs.

After securing its core IP, Pop Mart began taking strong measures against infringers and imitators.

Labubu’s evil twin

It may have seemed like Pop Mart could walk blissfully off into the sunset after hitting the hype sweet spot, but where there is hype, counterfeiters soon follow. The toy industry is a significant victim of the counterfeit market, which in 2022 was valued by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) at $464 billion. Whilst the internet allows a product to gain worldwide popularity, carving a path across the globe also makes it easier for fake versions to appear.

In Labubu land, “Lafufu” has become the widespread term used to refer to the counterfeit toys. “Lafufus” have become almost as sought-after as Labubus for various reasons, including their lower price tag, extra, unique features, or even just a wish to go against the mainstream. They have become so popular that Lafufu manufacturers, small factories which are mainly located in the Guangdong and Hebei provinces in China, are also struggling to meet demand. They may seem like silly, affordable toys but do they represent something more sinister?

Counterfeit goods are a threat to brand value and can seriously harm revenue streams. They can even be health risks to consumers, especially when it comes to children’s toys, as they are often poorly made. Not only are they a threat to Pop Mart and their customers, Chinese authorities are also concerned by what the mass of “Lafufus” means for China’s growing reputation as an IP powerhouse. Labubus are an example of China transforming creativity into business opportunity, rivalling other Asian countries with a significant global cultural influence, such as Japan and South Korea, whilst Lafufus undermine the country’s innovation and prevent fair competition.

Nevertheless, Pop Mart is not giving up. They continue to strengthen their efforts in maintaining their unique position in the market, demonstrating the importance of strong IP protection.

Brand enforcement

A key aspect of enforcing the protected status of a brand is carefully monitoring the market so that you are aware if counterfeit goods appear. Pop Mart has implemented identifiers on their products to make genuine Labubus distinguishable from frauds, such as scannable QR codes, serial numbers and unique packaging design.

Once counterfeit goods are identified, it is important to take rapid action to minimise damage to the brand. Pop Mart’s 2024 Annual Report notes that it “identified more than 10 forged authorisation letters, took down the domain names of 5 overseas websites selling infringing products, initiated 3 infringement lawsuits, and successfully intercepted over 1.3 million infringing products at customs, making every effort to safeguard the Company’s intellectual property.”

In 2019, Pop Mart filed an invalidation request with the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) to challenge the unauthorised registration of the Labubu design patent. The CNIPA panel declared the entire design patent for the Labubu figure (No. ZL201830002145.4), which had been filed and granted to another party in 2018, invalid. The ruling reaffirmed the company’s originality and legitimate ownership of the character’s IP rights.

IP collaboration

Although the internet frenzy may be tailing off, Pop Mart continues to maximise the potential of its IP by forming strategic partnerships with other brands. For example, on the 18th of September, UNIQLO launched a clothing line featuring the “The Monsters” illustrations. This involves drawing up a licensing agreement so that Pop Mart are remunerated for the third-party use of the Labubu brand, as well as to ensure that the use aligns with Pop Mart’s wishes and there is no misuse of their image.

Holding the copyright to his creation, Kasing Lung profits from licensing deals and has now taken Labubu a step further, partnering with luxury Parisian leather brand MOYNAT to release a collection of Labubu-adorned handbags and leather accessories, which became available on the 11th of October.

Conclusion

Some people may think that Labubus have sent the world crazy, but, although their cuteness remains subjective, there is no doubt that they are an insightful case study on business strategy in a digital world, including the necessity of building and maintaining a robust IP portfolio. When the internet means that an individual’s or business’s creation could go viral overnight, a rigorous strategy for protecting IP, as well as surveillance of third-party use, is crucial.

Pop Mart’s success is no coincidence. Its strong IP framework sets a model for the designer toy industry, ensuring early copyright registration, strategic trademark protection and design rights for distinctive products. A vigilant infringement monitoring system allows the company to respond swiftly to counterfeits through legal and administrative action, safeguarding both brand value and market integrity.

The Nobel Prizes are some of the most prestigious awards available to creators, leaders and scientists in the world. Awarded by the Nobel Foundation, the prizes commend those that have achieved greatness in the six available categories: Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature, Economic Sciences, and Peace.

In this article, Associates Max Ziemann, Clare Pratt and Greg Jones examine the innovation behind the laureates that have been granted the Nobel Prizes of this year, discussing the award-winning innovation that have taken home the prizes in their specialist areas.

Nobel Prize in Chemistry by Max Ziemann

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in the field of Chemistry to Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar M. Yaghi for the development of metal–organic frameworks

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) are a type of macromolecule having an extended structure made of metal ions and organic linkers in a repeating pattern. In many cases, MOFs contain large pores within their molecular structures, which are able to take part in ‘host–guest chemistry’, i.e. holding smaller molecules in place within the pores.

Richard Robson first modelled MOF-like structures with metal ions and organic building blocks in 1974 during his time at the University of Melbourne. He considered the potential in linking different types of molecules together to form a diamond-like lattice structure, instead of using individual atoms. In 1989 Robson designed a tetrahedral nitrile containing ligand (4′,4′′,4′′′,4′′′′ tetracyanotetraphenylmethane) which was able to form a co-ordination complex with copper in a repeating tetrahedral lattice providing large pores between the copper centres. Robson theorised that the pores within such structures could be used to catalyse chemical reactions. However, these early MOFs lacked the chemical stability for such a use.

In 1997 Susumu Kitagawa designed a three-dimensional MOF using cobalt, nickel, or zinc in combination with 4,4’-bipyridine to form an MOF structure intersected by open channels and providing spaces that could be filled with gas (methane, nitrogen, oxygen, etc) whilst retaining stability. Kitagawa also pioneered flexible MOFs which can change shape, for example when they are filled or emptied. Flexibility of the MOF structure can lead to significant changes in their physical and chemical properties. This has a major impact on the adsorption and desorption of guest molecules from pores within the MOF which allows for fine-tuned adsorption and desorption in response to external stimuli.

Omar M. Yaghi was responsible for coining the term MOF in 1992. In 1995 Yaghi achieved crystallisation of metal-organic structures using metal ions and charged dicarboxylate linkers, as well as removal of guest molecules to provide a highly stable and porous structure. Yaghi’s lab first synthesised ‘MOF-5’, a MOF of the formula Zn4O(BDC)3 where BDC2- is terephthalic acid. MOF-5 is notable for exhibiting one of the highest surface area to volume ratios of any MOF, at 2200 m2/cm3, which is approximately a football pitch worth of area within the size of a sugar cube. Various analogues of MOF-5 have since been developed with differing dicarboxylate linkers in order to fine tune the dimensions of the cavities.

This combination of properties gives MOFs an enormous potential for gas storage within the pores of the MOF structure. Yaghi’s group have even designed MOFs that are capable of harvesting atmospheric water from desert air simply by trapping water molecules in specialised pores. Flexible properties and enormous surface area to volume ratios allow for very large volumes of gas to be stored and released at will within an MOF structure. MOFs can also be tailored for gas separation, such as carbon capture applications. MOFs therefore have a huge potential in environmentally beneficial technology including both capture and storage of greenhouse gasses (CO2, methane, NOx, etc) as well as storage and controlled release of alternative fuels such as hydrogen.

Kitagawa, Robson, and Yaghi have made considerable scientific contributions to the field of chemistry, which will no doubt continue being developed for key climate change mitigation strategies including absorption of greenhouse gases and providing water security.

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine by Clare Pratt

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi for their groundbreaking discoveries concerning peripheral immune tolerance, the mechanisms by which our immune system spares our own tissues while still defending against pathogens.

A major challenge for the immune system, which encounters countless microbes, bacteria, viruses, and other threats every day, is to ensure that immune responses do not mistakenly target the body’s own cells. When this regulation fails and the immune system attacks self-tissues, autoimmune disease results. The prevailing understanding had been that an immunological process called central immune tolerance, the elimination of any developing T or B lymphocytes that are autoreactive in the thymus, was primarily responsible for preventing such reactions. However, the laureates are recognised this year for uncovering the complementary and crucial role of peripheral immune tolerance.

In the 1990s, Sakaguchi carried out experiments in mice that had their thymuses removed. These mice developed severe autoimmune disease, suggesting that mechanisms beyond thymic deletion were needed to maintain tolerance. Further research led him to identify a subset of CD4⁺ T cells expressing CD25 (the IL-2 receptor α-chain), classed as regulatory T cells (Tregs), which act as a “brake” on the immune response and protect the body from autoimmune attack.

This was followed by work from Brunkow and Ramsdell who, while studying a mouse strain known as scurfy, discovered a mutation in the Foxp3 gene that caused severe autoimmune disease. In 2001, they demonstrated that mutations in the human ortholog, FOXP3, cause IPEX syndrome (Immune dysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-linked).

Two years later, Sakaguchi built on these findings, showing that FOXP3 is a master regulator of the development and function of regulatory T cells, and that these cells regulate immune activity to ensure the body’s defences do not turn against itself.

Their discoveries opened a new field in immunology, peripheral tolerance, and have become vital to the development of new medical treatments. These insights are informing therapies for autoimmune diseases and organ transplantation, where modulating regulatory T cells may improve graft acceptance and reduce the need for long-term immunosuppression. They have also paved the way for novel approaches in autoimmunity and cancer immunotherapy, where targeting regulatory T cells is an area of active clinical research.

The Nobel Prize in Physics by Greg Jones

Awarded to John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret and John M. Martinis for the “discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantisation in an electric circuit.”

Those that are familiar with quantum technology and the associated developments of quantum sensors, computers and cryptography, might already be aware of the pivotal work of Martinis, Devoret and Clarke in this field. Their contributions have been fundamental in helping to bridge the gap between theory and the practical applications of quantum mechanics.

Through experiments performed in 1984 and 1985at the University of California, the future Nobel Laureates investigated the whether quantum mechanical effects could only be demonstrated at a microscopic scale with the examination of only a small number of particles. At that time, a common belief was that quantum mechanics was limited to a much smaller scale, and could not be visibly demonstrated in larger, macroscopic objects.

Using a superconducting electrical circuit (an electrical circuit which has no electrical resistance), the trio used an approximately 1cm2 silicon chip containing a Josephson junction (a thin layer of non-conductive material between the superconductors within the circuit) to explore the outcome when a current passed through the circuit. The measurement of the voltage across the Josephson junction provided direct evidence that quantum mechanics could be an influence in macroscopic systems, by showing that quantum tunnelling had occurred through the Josephson junction, a phenomenon that is impossible through a classical ‘non-quantum’ model of physics.

Their research not only expanded the understanding of quantum mechanics but also demonstrated the potential for practical applications at a larger scale.

We are delighted to be sponsoring the MassChallenge UK Awards 2025 on Thursday 23 October, an event that will mark the closure of their reputable Accelerator Programme.

The evening will look to celebrate the 40 startups and small businesses that have been supported by the programme this year, which has enabled the participants to gain access to C-Level connections, office spaces in The Royal Docks, invaluable mentoring, and much more.

The impressive finalists this year include startups from a wide range of sectors such as AI, health tech, and sustainable food. Each of the businesses have already demonstrated remarkable potential, not only through their innovative ideas, but also through their ambition to create meaningful impact within their relevant industries.

MassChallenge UK will be awarding a total of £20k in cash prizes throughout the event, reflecting their commitment to supporting the startup ecosytem in a way that is significant and meaningful. In this way, the awards are a great opportunity for attendees to gain both recognition and valuable financial support.

Partners Paul Cozens, Andrea McShane, Max Thoma, and Managing Associate Adam Gilbertson will all be attending the ceremony and presenting awards, recognising the achievements of some of the standout finalists.

As a partner of MassChallenge UK, we strongly look forward to celebrating the successes of the growing startups throughout the evening, and we are excited to see what the future holds for each of them as they continue to grow.

To sign up for the event, click the link here.

Find out more about MassChallenge UK here.

To mark Black History Month, we were delighted to welcome Romain Muhammad, CEO of Diversify World, to give an online talk to our Mathys & Squire team.

Romain Muhammad is a public speaker, DEI expert, and recruitment specialist who has over 15 years of experience in corporate leadership. His mission is to encourage more diverse and inclusive work places, which can often be achieved through increased awareness and education. He focuses on topics such as systemic inequality, privilege and anti-racism, which contributes to improved work environments and helps to make meaningful change.

He is the founder and CEO of Diversify World, a company that looks to support underrepresented communities within the workforce through their services of recruitment, consulting, learning and development, and research. Through the Diversify World, Romain works to help organisations ensure they are maintaining a fair and supportive working culture and ensure that talented candidates from marginalised communities do not face barriers to employment.

His impressive collection of awards includes being named in the Emerald Network Top 100 Inspiring Next Generation Muslims 2024 list, as well as being the Top 50 Most Influential Muslim in Europe Winner 2023. He has also been awarded an Aziz Foundation Scholarship and an Honorary fellowship at the Royal Historical society, acting as further evidence to his great work and knowledge. He has also acted as a representative for marginalised communities on multiple occasions and holds a widely recognised reputation.

In his talk, ‘Redefining Narratives’, Romain spoke about the misconceptions regarding Black history and identity, specifically touching on how the UK media and education system has misinformed many of us on the reality of Britain’s history. Through numerous historical examples, such as artefacts and artworks, Romain demonstrated how diversity in Britain was evident centuries before we were taught, directly challenging these mainstream perceptions. It was a truly insightful talk, and our staff were very much appreciative for his time and learnt a lot from the session.

Click here to read more about our Diversity and Inclusion policies.

We are delighted to announce that we have maintained our ranking in the Chambers and Partners 2026 guide, marking our 15th year being recognised in the directory.

The 2026 edition of the Chambers and Partners UK Legal Guide highlights some of the most highly regarded law firms and legal professionals across the country. Each year, the guide is the result of an in-depth research process, during which analysts conduct investigations and hold one-on-one interviews to gather comprehensive insights into various areas of law.

The guide included the following testimonials for Mathys & Squire:

“The team at Mathys & Squire have deep scientific understanding of the biotech sector. They operate as true strategic partners who grasp the scientific nuances of our innovations.”

“Mathys & Squire have people who have a strong grasp of the engineering aspects of our product.”

“M&S have consistently provided the highest quality service and have worked extremely closely with all levels of our organisation.”

Amongst the team, Partner Martin Maclean has also been ranked as a Band 1 Patent Attorney, with the following testimonials:

“Martin always goes above and beyond and provides the best advice.”

“His client service is consistently outstanding. He is responsive, thoughtful and highly attuned to the fast-paced and often unpredictable nature of startup life.”

For more information on the Mathys & Squire rankings, visit the Chambers and Partners website here.

An interview with Partner Claire Breheny was recently featured in ‘Growing interest in non-alcoholic beverages opens new opportunities for brands’ by World Trademark Review. Claire provided commentary on how businesses looking to meet the heightened demand for non-alcoholic and low alcohol alternatives must ensure that their intellectual property strategy aligns with their new goals.

The article explores how shifting to non-alcoholic products is likely to have a positive impact for businesses. Firstly, a more extensive product line means a greater number of potential customers and, secondly, product advertising will be less bound by laws on alcohol advertising, making the brand more appealing to licensees. Claire highlights the fact that the market is still evolving and, despite large brands already offering non-alcoholic beverages, there is space for emerging brands to thrive if they position themselves in the right way.

To read the full article click here.

We are honoured to share that Mathys & Squire is a Silver sponsor of the WIPR Trademark and Brand Protection Summit 2025, taking place from the 28th to the 29th of October in San Francisco. Partner Claire Breheny will be attending the event in person.

The World Intellectual Property Review is the principal online publication for professionals in the IP industry, publishing news and guidance on the current issues facing businesses and legal practitioners.

WIPR organises the Trademark and Brand Protection Summit to connect prominent trade mark experts, including both the largest and most innovative brands and leading outside counsel. The event provides a pivotal opportunity to engage with like-minded peers and discover valuable insights into trade mark prosecution and enforcement in light of recent disruption for brand owners, such as AI and domain-related issues.

The program offers expert-led sessions and interactive panels designed to share a wide range of expertise in the latest legislative developments, strategic approaches to safeguarding your brand and how to maintain a competitive edge in an ever-changing global marketplace. On the 28th of October, Head of Trademarks Claire Breheny will be moderating a panel discussion on “Overcoming the Growing Problem of Domain Squatting and Trademark Misuses Online.” Alongside the other speakers, she will be sharing her in-depth knowledge on using innovative tools to detect infringers, and how to combat infringement cost-effectively and quickly.

For more information on the event, visit the website here.

Contact our team

Claire Breheny – Partner | [email protected]