Mathys & Squire is pleased to congratulate its client, Enapter, on winning the ‘Fix Our Climate’ category at The Earthshot Prize ceremony in London on Sunday 17 October 2021.

The initiative was launched in 2020 by Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, and Sir David Attenborough, with an aim of rewarding organisations dedicated to climate action through project funding, covering five ‘earthshot’ goals for the planet: ‘Protect and Restore Nature’, ‘Clean Our Air’, ‘Revive Our Oceans’, ‘Build a Waste-Free World’ and ‘Fix Our Climate’.

Enapter has developed leading AEM Electrolyser technology to turn renewable electricity into emission-free hydrogen gas that can fuel cars, planes and heat homes. The £1 million prize will enable them to mass produce their technology, expand their team, and invest more in research and development, in a bid to provide 10% of world’s hydrogen generation by 2050. The company, which has a global presence in Italy, Germany, Thailand and Russia, has also recently broken ground on the construction of its new mass production site in Saerbeck, Germany.

Mathys & Squire and Mathys & Squire Consulting have worked very closely with Enapter for a number of years, supporting them in the growth and valuation of their intellectual property portfolio, as they expand and revolutionise the world of renewable energy. We are extremely pleased to hear the news and wish the Enapter team continued success!

The UK government released its National Artificial Intelligence (AI) Strategy on 22 September 2021, following guidance from the AI Council’s 2021 AI Roadmap and other related plans – the Innovation Strategy and National Data Strategy. Among other topics, the National AI Strategy (the strategy) will involve a consultation on AI and intellectual property (IP) with the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO).

Since the AI Roadmap was published in March 2021, the UK government has been encouraged by the AI Council to produce an official strategy. Six months on, the strategy outlines how the UK aims to boost AI capabilities over the next 10 years, with the culminating goal to ‘make Britain a global AI superpower’.

The plan is broken down into three main ‘pillars’:

(i) investing in long-term needs of the AI ecosystem;

(ii) supporting the transition to an AI-enabled economy, while making sure all sectors can benefit from it; and

(iii) ensuring the UK gets the governance of AI technologies right.

Each of these pillars has associated short-, medium- and long-term key actions, along with a promise of a more detailed and measurable plan being released later this year.

One of the short-term plans is to complete a consultation on copyright and patents for AI in collaboration with the UKIPO. The strategy acknowledges that IP plays a significant role in building a successful business by rewarding people for inventiveness, creativity and enabling innovation. IP is noted for supporting business growth by incentivising investment, safe-guarding assets and enabling the sharing of know-how. The strategy further recognises that AI researchers and developers need the right support to commercialise their IP and help them to understand and identify their intellectual assets, providing them with the skills to protect, exploit and enforce their rights to improve their chances of survival and growth.

The strategy also recognises that for the UK to become a ‘science superpower’ and ‘the best place for researchers to innovate’, it needs an IP framework that gives British entrepreneurs, innovators and businesses a competitive edge. Among other things, the strategy promises to evaluate patentability of AI inventions, and to conduct an economic study to enhance understanding of the role the IP framework plays in incentivising AI investment.

The remaining short-term goals focus on supporting the Department of Education in developing AI skills and publishing subsequent AI strategies – the Defence AI Strategy and National Strategy for AI-Driven Technologies in Health and Social Care. Overall, the first three months are focused on data gathering and setting out the foundations for the framework to be implemented.

After the initial three months, the medium-term stage will involve the government looking to analyse all collected data and begin acting on it. The agenda includes a roll-out of new visa regimes to attract the world’s best AI talent and investing in AI programmes for schools, as well as encouraging a wider range of people to enter AI-related jobs. All these measures will ensure the UK has enough qualified workers now, and in the future, to sustain the UK’s new AI-driven economy. In addition, the government plans to publish a white paper on a pro-innovation position on regulating AI, in an effort to govern AI correctly. The strategy realises that AI is not currently unregulated, but it also recognises there are areas for improvement.

The long-term strategy will involve launching a new National AI Research and Innovation Programme to align funding initiatives: updating guidance on AI ethics and safety, as well as considering which machine-readable government datasets can be published for AI models. The government also intends to take on larger challenges, such as encouraging diversity in AI and including trade deal provisions in AI.

A more detailed and measurable plan for the execution of the initial stages of the strategy is expected towards the end of the year.

We will follow with interest the government’s progress in tackling the outlined action plans as part of its strategy to make the UK an AI superpower, and are pleased to see that IP has been identified as an important tool in achieving this goal.

In this article for The Patent Lawyer, Mathys & Squire partner Dani Kramer and associate Dylan Morgan review the response of patent offices to blockchain filings with a particular focus on the United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO), the European Patent Office (EPO), and the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

In the last decade or so, blockchain has become an area of increasing interest both commercially and from a patenting perspective. While blockchain has not yet become a part of daily life for most people, the technology can be applied to many fields and offers the potential to improve various existing technologies. Unsurprisingly, many companies are keen to protect their blockchain developments via patents.

Throughout this article, comparisons between patent offices will be drawn in particular by comparing the treatment of exemplary patent families in the various offices. In general, most of these jurisdictions seem to be amenable to blockchain filings. The exception to this is the UKIPO, which has granted relatively few blockchain patents and has objected to many applications on the basis of unallowable subject matter. Thus, at least for the time being, applicants seeking protection for blockchain inventions in the UK might be best served by pursuing patent protection via the EPO.

Introduction

The majority of patent offices have yet to rule on the patentability of blockchain in any seminal cases, and present guidance from patent offices is typically that blockchain inventions should be treated the same as other computer-implemented inventions.

For example, in a conference report titled ‘Talking about a new revolution: blockchain’ from 4 December 2018, the EPO set out its position that: “… blockchain inventions are essentially computer-implemented inventions (CII), so they are examined by the EPO according to established stable criteria, developed in accordance with CII case law.”. “Realising that blockchain inventions are in fact CII is a big relief,” said Lievens. “We are on known territory. We know how to do this. Applicants will have legal certainty and will get what they expect.”

Other patent offices have taken similar positions, that blockchain inventions should be treated much the same as any other computer-implemented inventions.

Of course, in practice different types of computer-implemented inventions can be treated rather differently by different patent offices. Below, we have compared the treatment of blockchain filings by certain offices to identify any discernible trends.

UKIPO

There have been hundreds of blockchain filings at the UKIPO, with most of these applications being filed within the last five years. Many of these applications have not yet received search or examination reports and so there is a limited pool of filings from which conclusions can be drawn.

However, enough applications have been examined to observe an apparent pattern of UK blockchain filings being rejected on the basis of unallowable subject matter.

An indicative application is GB2555496A, filed in 2017 by Trustonic. Corresponding applications have been filed in Europe (EP3312756B1) and the US (US20180114220A1) – and these applications will be commented upon later.

In a first examination report for the UK application, the Examiner stated:

“I note that the US equivalent to this application has been abandoned following significant amendment, and the EP equivalent granted again following significant amendment (note conflict warning below.) Given also the substantive excluded matter objection, which would not in my view be addressed by either the US or EP form of claims, I have not therefore at this stage completed an updating top up search on this application.”

While this application is still pending, it seems that overcoming these objections will be challenging. This examination report is also interesting because it succinctly expresses a number of conclusions that are borne out of our review of other UK filings. In particular:

- Blockchain filings are likely to draw subject matter objections at the UKIPO.

- The UKIPO seems to take a harsher stance on blockchain filings than other offices.

- The UKIPO is typically unwilling to perform searches until subject matter objections have been addressed.

This being said, certain companies have managed to secure patent protection for blockchain inventions at the UKIPO (e.g. via GB2549085B and GB2561107B).

Filings that manage to achieve grant in the UK are typically linked to a physical system or input; for example, the claims of GB2561107B require the obtaining of biometric data and the comparison of this biometric data to a biometric hash.

EPO

As will be apparent from the Examiner’s comments in the UK examination report cited above, the EPO is generally more amenable to blockchain inventions than the UKIPO.

Indeed, for EP3312756B1 (the EP filing in the above-mentioned Trustonic patent family) the Examiner’s objections were almost entirely related to novelty and inventive step, with the patentability per se of the subject matter attracting very little attention.

This trend is played out across European patent filings. Novelty and inventive step tend to be the determining factors, with patentable subject matter tending to be of subsidiary relevance. This is partially due to the way in which the EPO approaches inventive step – and as with all applications, non-technical aspects are of limited relevance during the determination of an inventive step – but, as a general rule, the EPO seems willing to consider blockchain technologies as being technical and to more readily grant blockchain patents.

Another application that illustrates this difference in approach between the EPO and the UKIPO is EP3577593B1, which was filed by PHM Associates in 2018 claiming priority to a GB application filed in 2017. On the face of it, this is a fairly innocuous European application. Following entry into Europe via a Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) application, the Examiner raised various novelty and inventive step objections. Once these were overcome, a patent was granted by the EPO.

Conversely, the corresponding UK application GB2566741A has thus far received a total of four examination reports from two different examiners, with each of these examination reports objecting to the claims as relating to unpatentable subject matter.

Turning then to an application that has fallen foul of EPO subject matter objections, EP3376456A4 is an application filed by Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corp in 2016 that relates to the determination of whether a party is qualified to add blocks to a blockchain. This application has been refused by the EPO Examining Division and is currently under appeal.

Justifying the refusal, the Examining Division stated:

“The present application relates to decisions for granting the right to generate the next block in a blockchain as typically used in cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin.”…

“This problem is addressed by a blockchain generation and verification method in which the decision for granting the right to generate the next block in a blockchain is based on the number of “transaction patterns”, i.e. the number of transactions with different transaction partners in which a party has participated (e.g. determined in the form of the sum of the number of unique identifiers of transaction partners in the transaction datasets). This is regarded as an index of trustworthiness of the generating party based on the assumption that a transaction is conducted with trust on the transaction partner built by revealing each other’s identities and knowing who the transaction partner is. …”

“The problems which are thus addressed do not appear to refer to a technical solution of a technical problem, but rather address business-related or behavioral considerations for the selection of a parameter in a consensus algorithm.”

This decision makes it clear that not all blockchain applications will be considered by EPO examiners to be technical in nature and hence allowable by the EPO. In particular, those applications that are interpreted to be business methods per se (and inventions relating to consensus mechanisms might be at increased risk of this) are likely to face difficulty at the EPO, unless – as with any computer-implemented or business method invention – it is possible to demonstrate a clear technical effect. As mentioned above, this application is currently under appeal, and the outcome of this appeal might well have implications for future blockchain applications.

In summary, the EPO has shown itself willing to grant blockchain patents – but applicants should be careful in particular to avoid straying towards business methods.

USPTO

Turning to US practice, it is useful to consider again the patent families that have been mentioned previously – the Trustonic, PHM, and Nippon families.

The US application in the Trustonic family (US20180114220A1) received a first Office Action that raised numerous patentability objections. The claims were rejected under 35 USC § 101 as being “Certain Methods of Organizing Human Activity”.

Following a response from the applicant, and the issuance of a subsequent final Office Action, the application was abandoned.

Relevant extracts from that final Office Action include:

- “Applicant also argues that rather than verification of the chain of trust being implicit from the authentication of one stakeholder by another stakeholder, the chain of trust can be verified using a public ledger which tracks the chain of cryptographic identities established for the electronic device to improves the way in which a new cryptographic identity is established for an electronic device. The Examiner respectfully disagrees. The specifics of how the verification works is not reflected in the claims. Besides, transfer token and values of the counter are non-functional descriptive material and are not functionally involved in the steps recited.”

- “Claim 20 recites [a] similar abstract idea. That is, other than reciting “electronic”, “digital” nothing in the claim element precludes the step from practically being organized by human activity.”

In contrast, the US application in the PHM family has received no subject matter objections under 35 USC § 101. Similarly, the US application in the Nippon family received no subject matter objections under 35 USC § 101 and has recently proceeded to grant.

While the Trustonic US application received subject matter objections, it is notable from the above extracts that these objections do not focus on the blockchain aspects. Furthermore, the case file contains an Examiner’s summary of an applicant interview that suggests the objections could have been overcome with further amendments.

More generally, it is notable from a review of US applications that the ‘abstract idea’ objections faced by blockchain inventions at the USPTO seem more likely to be surmounted than subject matter objections at the UKIPO or EPO. For example, US10291627B2 is a patent filed by ARM in 2016 and granted in 2019 and US10803022B2 is a patent filed by Uledger in 2018 and granted in 2020. Each of these filings faced initial subject matter objections that were overcome via amendment and argumentation.

Comparatively, blockchain filings seem to be viewed relatively favourably by the USPTO – and in many cases where subject matter objections have been raised, it has proved possible to overcome these objections.

Summary

In summary, most patent offices seem to be willing to grant blockchain patents – and although they have not been discussed here, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) and the Japanese Patent Office (JPO) also seem to be willing to grant such patents.

As with other computer-implemented inventions it is helpful to show a clear technical effect and to illustrate that any claimed method could not be performed by humans. And as with other computer-implemented inventions, applications that stray too far towards pure business methods are at particular risk of receiving subject matter objections.

The UKIPO is perhaps a notable outlier that views blockchain filings somewhat unfavourably. Therefore, where UK protection is desired it might well be beneficial to seek patent protection by filing an application at the EPO.

This article was published in The Patent Lawyer Magazine in October 2021.

Mathys & Squire is pleased to be ranked in the PATMA: Patent Attorneys and PATMA: Trade Mark Attorneys categories in the latest edition of The Legal 500 – the definitive guide to the legal market. In addition to our firm rankings, we are delighted that a record number of fee earners have been individually recommended in the 2022 guide.

Patent partners Jane Clark, Paul Cozens, Chris Hamer, Alan MacDougall, Martin MacLean, David Hobson, Juliet Redhouse, Andrew White, Philippa Griffin, Dani Kramer, Anna Gregson and Craig Titmus, plus partners Margaret Arnott, Gary Johnston and managing associate Harry Rowe from our trade mark practice, have all featured in this year’s guide. Praise for our attorneys includes:

‘Chris Hamer and his team have put in a very good effort to understand our business and work very well with our inventors, despite their some times difficult mindset. We go to meetings enjoying the discussions and leave the meetings with a very good energy for moving ahead. Problem-solving is a big part of their mindset, highly appreciated by us. Difficulties and issues are for solving with never-ending energy and inspiration.‘

‘Philippa Griffin is a pleasure to work with. She has an exceptional grasp of our company’s technology and is extremely responsive and comprehensive in her analysis and communication of IP strategy.‘

‘Craig Titmus has been incredibly helpful and collaborative, helping us efficiently and guiding us through many scenarios to identify key risks and rewards with each strategy. It has certainly helped us define and secure our IP as well as getting it through the many hurdles international process patents require.‘

‘Andrew White is an exceptional patent attorney. He knows exactly the perfect way to construct a patent application, to consider an examiner’s feedback and to work round it to get the patent grant with minimal deviation from the original scope. He’s the best I’ve worked with in over 15 years.‘

‘Juliet Redhouse is an excellent patent attorney. She is very knowledgeable about both the science and the law, always well prepared for meetings, and easy to work with. I recommend her highly as a superb patent attorney.‘

‘David Hobson is top rate.’

‘What we liked especially was having one point-person to manage our affairs, right from initial no-obligation chat, to engagement, all the way through to resolution of the trade mark issue we were facing. We were very impressed by Harry Rowe’s professionalism from the start. The whole process ran very smoothly and was painless and cost-effective, and we were very happy with the advice we received and the result achieved. We wouldn’t hesitate to recommend Harry Rowe personally and M&S in general in resolving a tech-related trade mark issue.’

The firm also received glowing testimonials for its patent and trade mark practices:

‘The people make the team as they say. This team is made with perfection, collaboration is smooth and with a high mind to understand our business. Their knowledge and experience is outstanding for patent drafting, prosecution and also oppositions.‘

‘I have always found Mathys & Squire to be the most approachable and reactive of all the patent attorneys I have worked with. There is never the feeling that you are ‘on the clock’ and they always go the extra mile.‘

‘Immediate response on urgent situations. Full knowledge on how to deal with minute details that would pose a risk to the trade mark.’

‘Very strong in TMs and design rights both in the UK and worldwide.‘

‘We were very happy with the client service received, the advice given to us, and the result achieved by the lawyers at M&S.’

‘Very robust in terms of their position in the market. High gravitas.‘

‘Always on hand to help and guides us through often complex issues in a professional way with plain English.’

For full details of our rankings in The Legal 500 2022 guide, please click here.

We would like to thank each of our clients and contacts who took the time to participate in the research.

Through years of education and hands-on experience with clients, our team of patent and trade mark attorneys have built expertise in all areas of intellectual property (IP) in the pharmaceutical sector. To celebrate World Pharmacists Day (25 September 2021), Mathys & Squire is assessing the impact and distinctiveness of IP in the pharmaceutical industry.

IP increases company value

One way to protect intangible assets and IP is to obtain patents, which can be used to prevent infringements, as well as boost innovation and drive research and development (R&D). Patents bring reassurance to investors that an invention can be commercially successful, and that the company has exclusive monopoly in relation to a particular product. Specifically, in the pharmaceutical industry, an effective IP strategy provides businesses with confidence that, subject to marketing approval, they will be able to market the drug. This can drive further motivation and importantly, investment. The majority of pharmaceutical company’s value is wrapped up in its patent and trade mark portfolio, so a robust IP strategy is vital to its success.

Use of supplementary protection certificates to extend a patent’s validity

Most patent applications are filed during the R&D stage, so obtaining a patent also gives pharmaceutical companies the space and time needed to develop medicinal solutions and enter clinical trials, without the risk of any associated disclosures preventing them from obtaining a patent. This enables businesses to invest in the long-term, complicated, and risky process of developing medicines, as they have legal measures in place that prevent third parties from using their invention for 20 years.

Another aspect that impacts IP in pharmaceutical companies is the lengthy drug development process and complex requirements to obtain marketing authorisation. With inventions being patented very early on in the R&D process, drugs often make it to the market with only a few years of patent life remaining. Once their drug(s) have made it to market, pharmaceutical companies must also adhere to The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) Code and disclose full details of the chemicals used in a particular drug, which makes the invention vulnerable to copying by competitors when the patent expires. This poses a problem as a patent’s remaining validity may not be long enough to bring a return on the investment, and as a direct response to this, legislators have introduced supplementary protection certificates (SPCs). This IP right has the power to extend a patent’s validity by a maximum of five years and is therefore very popular amongst pharmaceutical companies.

Patents give price setting freedom

IP in pharmaceutical companies is also crucial when it comes to setting the price for a drug. A patent grants a temporary monopoly on an invention, meaning the inventor can charge higher than normal prices, as there is no competition in the market. However, once the patent loses its validity, competitor generics may enter the market, typically at much lower prices. Protecting intangible assets and IP has a direct impact on a business’ profitability, so having a team of experienced patent and trade mark attorneys offering advice is key to a company’s success.

The patent application drafting process gets more complex

Drafting a patent application can be challenging as it can require a lot of detail to convince Intellectual Property Offices that an invention is different from anything else already on the market – i.e. that it is inventive – and at the same time provide enough technical detail for somebody to ‘work’ the invention. Initially, a patent application may be filed with some details omitted, but it is normally advisable to incorporate as much detail (and experimental support) as possible during the first 12 months from filing. Timing is critical because no new information can be added to a patent beyond the 12-month stage. As the full drug development process can take up to 15 years, it is challenging to anticipate the final results of that research phase in the first 12 months. More than likely, there will also be multiple pharmaceutical companies trying to fill the unmet medical demand with their own inventive molecules, which makes it much more difficult to differentiate the proposed offering from existing drugs or patent applications. For these reasons, it is crucial for a pharmaceutical company to have a secure invention capture process in place and to keep accurate lab book notes to allow for effective patent filing.

It is widely recognised that IP rights are essential, especially for pharmaceutical companies, to allow for continued innovation of new medicines. Thanks to the pharmaceutical revolution, people have a longer life expectancy, better life quality and improved comfort of living. Mathys & Squire is pleased to celebrate all pharmacists this World Pharmacists Day, and in particular, our innovative clients in the pharmaceutical industry!

The number of blockchain patent filings has exploded in recent years at almost every patent office, but as of yet there have been very few decisions on the patentability of blockchain above the level of patent examiners. Patentability has mostly been decided by individual examiners following the guidance for more general computer-implemented inventions – and this has led to a degree of inconsistency between patent offices (though of course this occurs with many types of invention) and between examiners at individual offices.

Fortunately, a recent decision of the Australian Patent Office: Advanced New Technologies Co., Ltd. [2021] APO 29 (21 July 2021) casts some light on the patentability of blockchain in Australia and offers guidance that might be followed by other patent offices.

In short – at least in Australia – it seems as though blockchain is by and large patentable subject matter.

The decision relates to the patent application AU2018243625, an application filed by Advanced New Technologies Co., Ltd with a filing date of 21 March 2018 and a priority date of 28 March 2017.

Chronologically:

- A first examination report issued on 23 January 2020 asserted that all the claims were directed to unpatentable subject matter and lacked an inventive step.

- Following some back and forth, the applicant managed to convince the examiner that the claims were inventive, but in a fourth examination report issued on 7 January 2021, the examiner maintained the position that the claims were directed towards unpatentable subject matter (the examiner also introduced a new objection that the specification did not provide a clear and complete disclosure of the claimed invention).

- The applicant responded on 22 January 2021 requesting to be heard in relation to the outstanding objections and filed submissions explaining why these outstanding objections should be withdrawn.

Turning then to the substance of the application, the application states that: “there is a need to solve the technical problem of how to design a method for verifying a transaction request, such that there is no risk for privacy breach of a blockchain node participating in the transaction”.

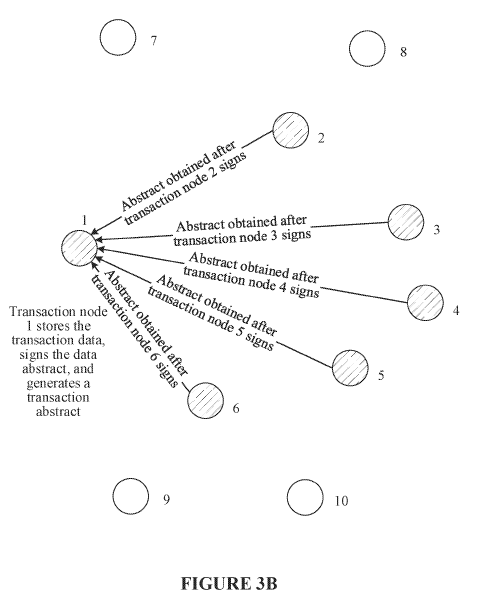

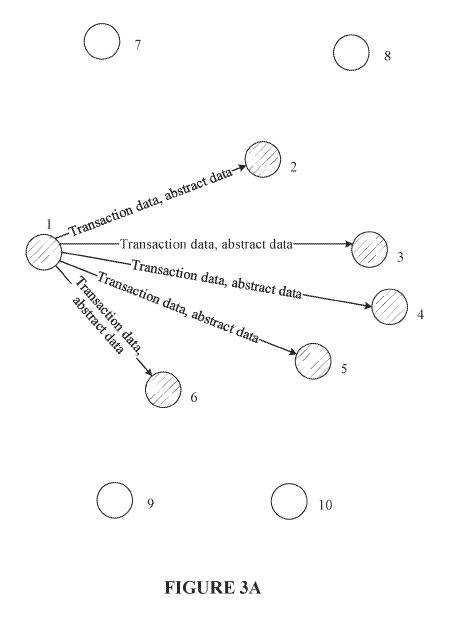

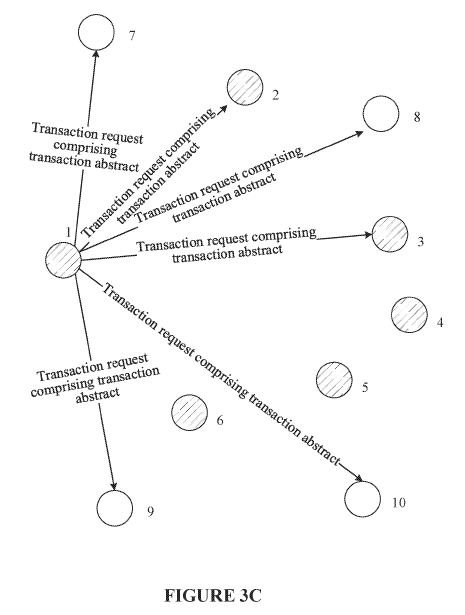

The invention proposed to solve this problem is illustrated by figures 3A – 3C of the application, which are reproduced below:

The claim 1 proposed by the applicant’s submissions is rather long, and therefore is not copied here in full, but essentially the claim relates to the generation and broadcasting of a transaction request in order to “caus[e] the consensus nodes to each save the transaction abstract in the transaction request into a blockchain after the transaction abstract passes the consensus verification”.

The examiner was of the opinion that the invention “concerns the mere implementation of an abstract idea in an unspecified manner within a particular computer/computing environment”.

More specifically, the examiner argued that: “it becomes apparent that the substance of the invention lies in the abstract idea of not sending particular information as part of the transaction processing. Moreover, it is evident from the specification that the substance of the invention lies solely in the content of the data rather than any technical intervention on the part of the inventors.”

Turning then to the decision, the delegate of the commissioner did not agree with this view of the examiner. The standout statement made by the delegate is the statement that: “I can see no reason why technical improvements to fundamental mechanisms related to consensus within a blockchain should not be patentable, even though these improvements might not necessarily be addressing technical problems. In my view, the balance of considerations weigh in favour of finding that the claimed invention is a manner of manufacture.”

This is of course good news for patent practitioners looking to patent blockchain technologies and confirms the patentability of even core blockchain inventions (at least in Australia).

It is worth mentioning that this view (i.e. that blockchain inventions are technical and patentable) is not unusual. Most patent offices are amenable to blockchain inventions to some extent at least, though it is notable that the UK Patent Office tends to view blockchain inventions unfavourably (with only a small number of blockchain patents having made it through to grant in the UK). It is however encouraging to receive such a positive decision from a higher authority than an examiner.

Turning back to the decision, the delegate later stated: “However, I have serious concerns about the inventiveness of the claimed invention. I therefore refer the application back to examination in order to reassess the inventiveness of the claimed invention ….” – so while blockchain inventions seem to contain patentable subject matter, they do still need to be inventive! If anything, the fact that the invention was seen as not at all inventive but was still viewed as patentable subject matter should be viewed as very encouraging.

A conclusion that might be drawn from this decision is that for companies seeking blockchain patents, filing an application in Australia is a good idea. Additionally, examiners at many of the Asian patent offices (e.g. Indonesia and Malaysia, etc.) tend to concur with the decisions of examiners of the Australian Patent Office so this decision could be seen as a positive indication of blockchain patentability across much of Asia. When considering previous decisions by patent offices in Europe and the US, western patent offices are less likely to follow the Australian Patent Office so this decision is of less direct relevance, but is of course still an encouraging sign.

In summary, this decision seems to indicate the Australian Patent Office is amenable to blockchain patents – this is not a surprise, but rather is an affirmation of current practices from a significant patent office.

Mathys & Squire is delighted that partners Anna Gregson, Dani Kramer and Martin MacLean have all been identified in the 2021 edition of IAM Strategy 300: The World’s Leading IP Strategists. Highlighting those who are leading the way in the development and implementation of strategies that maximise the value of IP portfolios, the guide lists individuals from service providers, corporations, research institutions or universities.

Heralded as ‘world-class IP strategists’, these individuals are identified through confidential nominations, followed by extensive research interviews with senior members of the global IP community, including senior corporate IP managers in North America, Europe and Asia, as well as third-party IP service providers. Following this process, only those with exceptional skill sets, as well as profound insights into the development, creation and management of IP value, are featured in the IAM Strategy 300.

The 2021 rankings are available via the IAM website.

We would like to thank our clients and contacts who took the time to provide feedback to the research team at IAM Strategy 300.

We are pleased to announce the appointment of Mathys & Squire’s first Chief Operating Officer (COO) in our 111-year history.

The management board has created the COO role to be responsible for driving forward the firm’s strategic development and growth. The COO will also play a key role in business leadership, improving operational implementation, efficiency and business transformation.

Mathys & Squire has gone through a period of sustained growth in recent years, appointing seven new partners in the last two years. This includes two new partners in the firm’s Munich office as we expand our European footprint.

Appointing a COO to play a larger role in running the business will allow for senior partners to able to spend a larger proportion of their time with clients and growing the firm rather than dealing with day-to-day operational matters.

The firm’s new COO is Jont Cole, who joins Mathys & Squire from property giant JLL, where he held senior roles including Global Strategic Program Director and COO of its Advisory and Alternatives divisions. At JLL, Jont led the coordination and implementation of the firm’s valuation global data strategy and global technology platform. He holds an undergraduate degree in Biochemistry and an Executive MBA from the London Business School.

Chris Hamer, partner and board member at Mathys & Squire, comments: “Jont’s appointment is a significant step in Mathys & Squire’s strategic development. His influence will allow the firm’s experts to focus on growing the business in the long term.”

Jont Cole comments: “I’m thrilled to be joining one of the leading European IP law firms with a superb reputation in the market for both its legal and commercial advice. I’m looking forward to freeing up senior partner time to serve clients even more fully.”

This release has been published in Intellectual Property Magazine, The Patent Lawyer and Legal IT Insider.

In this article for The Patent Lawyer, partner Jeremy Smith provides an update to his earlier comments regarding the South African patent office issuing the world’s first patent for an invention that lists an artificial intelligence (AI) as the inventor (available here), in response to news that the Australian Federal Court has now also handed down a decision that an AI can be named as the inventor in a patent application.

The patent application relates to two inventions: a beverage container having a fractal wall; and a signal beacon, both generated by DABUS (‘Device for the autonomous bootstrapping of unified sentience’) – an AI system created by Stephen Thaler. The patent application was filed with Stephen Thaler listed as the applicant and DABUS listed as the sole inventor, with the inventor field of the application stating that “The invention was autonomously generated by an artificial intelligence”. The court overturned a previous decision by the Deputy Commissioner of Patents of the Australian Intellectual Property Office to refuse the application on the basis that the Australian Patents Act requires the inventor to be human.

In its reasoning, the Federal Court emphasised the difference in requirements between being an owner and an inventor, noting that whilst only a human or other legal person can be the owner of a patent, the inventor is not restricted to being human. Regarding inventorship, the Court commented that “First, an inventor is an agent noun; an agent can be a person or thing that invents. Second, so to hold reflects the reality in terms of many otherwise patentable inventions where it cannot sensibly be said that a human is the inventor. Third, nothing in the Act dictates the contrary conclusion”. This was in disagreement with the Deputy Commissioner, who noted that the ordinary meaning of “inventor” is inherently human, following reasoning similar to that of decisions handed down in other jurisdictions, such as the UK, where the listing of DABUS as a non-human inventor has been rejected.

The court also provided some clarification on the issue of ownership when an AI is listed as the inventor, noting that whilst DABUS is not a legal person and cannot legally assign the invention, the invention was made for Dr Thaler in the sense that Dr Thaler is the owner, programmer and operator of the system that made the invention, and therefore, on established principles of property law, is the owner of the invention.

The news follows the recent development in South Africa, where a patent was recently issued that lists DABUS as an inventor. However, whilst the grant of a patent in South Africa that names an artificial intelligence as inventor also provides for attention grabbing headlines, we need to be careful not to infer too much from this occurrence. Unlike other countries in which patent offices had concluded that an AI cannot be considered an inventor under current legislation, the South African patent office does not carry out substantive examination of a patent application before grant. Instead, potential issues with a granted patent are left to the courts, should the granted patent ever be challenged. Accordingly, the grant of the DABUS patent in South Africa is not an indication that the South African patent office has accepted that an AI can, legitimately, be a named inventor – the patent office may simply not have considered the issue. Nevertheless, the decision by the Australian Federal Court is more significant and seems to open the door for non-human inventors to be named on patent applications in Australia.

As a practical matter, the divergence of approach between the Australian court other those of other jurisdictions raises potential conflicts for applicants wishing to obtain patent protection, in both Australia and elsewhere, for inventions involving the use of AI. For example, there may be scenarios in which it is impossible to name a single set of inventors that is legally correct in both Australia and another jurisdiction, such as the US.

This article was published in The Patent Lawyer Magazine in August 2021.

The recent decision by the European Patent Office (EPO)’s Technical Board of Appeal 3.3.04 in T 96/20 appears, at first glance, to have raised the bar for acknowledging the inventive step of medical use claims in a situation where the prior art discloses that the claimed therapeutic is undergoing clinical trials. However, a broader view suggests that a more nuanced approach is required.

There have been numerous decisions by the EPO’s Boards of Appeal which have demonstrated how clinical trial disclosures can become an obstacle to the patentability of medical use claims.

The Boards have repeatedly recognised the novelty of medical use claims over prior art disclosures indicating that clinical trials were underway, but whose results were not yet reported (e.g.T 158/96, T 715/03 and T 385/07). However, the disclosure that a therapeutic is undergoing clinical trials can nevertheless become a bar to securing an inventive step, even where the results of the trial have not been made available to the public (as discussed in e.g. T 2506/12 and T 239/16).

The decision in T 96/20, at first glance, appears to further raise the bar on inventive step. Here, the Board deems that the disclosure of a Phase II clinical trial protocol for eculizumab (Alexion’s anti-complement component C5 antibody; marketed as Soliris®) for the treatment of the neuromuscular disorder myasthenia gravis (MG), in and of itself, provides the skilled person with a reasonable expectation that the treatment would be successful.

The Board considers that this expectation would stand “unless there was evidence to the contrary in the state of the art”. The Board is not swayed by the appellant’s argument that MG was known to be difficult to treat in humans. In view of the complexity of the complement cascade and its implication in a variety of diseases, the Board also rejects the notion that reports in the art of failures to treat other complement-associated disorders using different types of inhibitors would diminish the skilled person’s expectation of success. Of interest, on this point, the Board states that:

“In view of this complexity, the board is satisfied that the failure of other complement inhibitors to treat diseases unrelated to MG did not necessarily call into question the skilled person’s expectation that MG could be treated successfully with Eculizumab. In fact, in the board’s view, only evidence relating to the same compound and disease would be suitable for this purpose”.

(Reasons 13; emphasis added)

Consequently, the appellant’s medical use claims directed to the use of eculizumab in the treatment of MG are deemed to lack an inventive step by the Board.

The notion that a Phase II clinical trial protocol may provide a reasonable expectation of success is not new. In T 239/16 the Board asserted that a reasonable expectation of success arises because clinical trials are known to be based on earlier preclinical studies (thereby suggesting the success of the therapeutic concerned) and because their approval entails ethical considerations which require that a benefit will arise with “reasonable certainty” (see 6.5 and 6.6 of the Reasons). In that case, however, the class of active agents to which the claimed therapeutic belonged was known to be generally effective in treating the condition in question and the Board decided that there was nothing in the state of the art to lead the skilled person to believe that the claimed once-yearly administration regimen (corresponding to one of the arms in the clinical trial) would not be effective.

The facts underlying T 96/20 are different to T 239/16, in that the claimed medical use is not a specific administration regimen and no effective treatment with the same class of active agents (anti-C5 antibodies) was known in the art. The Board nevertheless comes to the same conclusion, namely that the Phase II trial protocol provides a reasonable expectation that the therapy will be effective. Thus, in T 96/20 the Board seems to be further raising the bar because it appears to endorse a very rigid approach to the assessment of inventive step, in which the disclosure of a clinical trial protocol is automatically deemed to provide an expectation of success which is only diminished if there is evidence to the contrary in the prior art pertaining to the same therapeutic and the same disease.

Reaching such a conclusion would, however, mean disregarding much of the existing EPO case law indicating that a more nuanced approach is required and setting out multiple factors which must be taken into consideration and carefully balanced when establishing whether a prior art disclosure provides the skilled person with a reasonable expectation of success. A useful insight into the thought processes which may underpin the Board’s assessment of the skilled person’s expectations in T 96/20 is provided by decision T 33/19 which was issued by the same Board (3.3.04) in the same composition on the same date as T 96/20. That decision also pertains to medical uses of eculizumab, albeit for the treatment of a different condition (aHUS).

In T 33/19 the prior art did not include a clinical trial disclosure. Instead, the art suggested investigating anti-C5 antibodies as a therapeutic option for treatment of aHUS. The Board considered that this teaching in the art was merely speculative because it was not based on in vitro or in vivo experiments (anti-C5 antibodies had not been tested in an animal model for aHUS) and the art also expressed uncertainty as to the outcome of such a treatment. Thus, the Board concluded that a reasonable expectation that aHUS could be successfully treated with eculizumab did not exist.

The factors considered by Board 3.3.04 in T 33/19 align with those in earlier decisions pertaining to clinical trial disclosures, for example asking whether the therapeutic belongs to a class of compounds that was known to be effective in the treatment of the disease (which it was in T 239/16, but not in T 715/03). In T 96/20 the Board does not provide any written reasoning in response to the Appellant’s argument that, by contrast to T 239/16, eculizumab was the first complement inhibitor approved for the treatment of MG. That does not mean, however, that this factor was ignored by the Board in reaching its decision.

Another factor which is not discussed in the reasoning of T 96/20, but which is important to consider, is that the skilled person has at hand their own knowledge of the clinical trial application process and the varying criteria that must be met in order to receive approval for the different phases of a clinical trial. Whilst it might generally be the case that the approval of a Phase II trial indicates some expectation of success, it cannot be assumed that the level of expectation will be high in all cases. Approval of a Phase II trial does not automatically indicate that Phase I has concluded, neither does it imply any positive therapeutic outcome from Phase I. In reality, Phase I and II may overlap (as seen with the recent trials for the Covid-19 vaccines, for example).

The skilled person also has knowledge that certain clinical trials with specific risk factors may require additional experimental evidence and evaluations prior to approval, e.g. if the drug acts via a species specific mechanism such that animal models are unlikely to be predictive of activity in humans or where target expression differs considerably between healthy subjects and those with the disease[1]. On the other hand, the skilled person also knows that there are situations in which the level of supporting evidence required for Phase I approval is low, e.g. trials involving a known therapeutic for a new indication. The skilled person is also aware of situations in which approval of a drug for use in humans is based on minimal pre-clinical data. For example, it is known that the scientific evidence required for orphan drug designation can be minimal and, in some circumstances, may only be based on in vitro data[2]. In such cases, the expectation of achieving a safe and effective treatment is arguably closer to a ‘mere hope to succeed’ than to any ‘reasonable expectation of success’.

Taking all of the above into consideration, it becomes clear that the question as to whether or not the disclosure of a clinical trial protocol provides a reasonable expectation of success is undoubtedly highly subjective and based on a balance of several factors. To assert that there is automatically an expectation of success in every situation which is only diminished by evidence pertaining to the same therapeutic and the same disease seems to set the bar too high. Moreover, it would neglect all of the above considerations and circumstances which are critical to evaluating the skilled person’s ability to make a rational and informed prediction as to whether the envisaged treatment would be successful. The fact that the same Board was clearly aware of these factors in their decision T 33/19 indicates that the reasoning in T 96/20 is not intended to depart from the earlier case law of the Boards of Appeal in this area.

For this reason, we consider that T 96/20 should not be seen as a radical departure from earlier EPO jurisprudence, nor should it be seen as a reason to disregard the above considerations. It should, however, act to highlight the complexities of EPO practice in this area and as further encouragement (if any were needed) to applicants and patentees to provide as much evidence as possible about the low expectation of success of the skilled person based on the state of the art, especially where that includes Phase II clinical trial protocols.

Summary of factors which may influence the skilled person’s expectation of success

Factors which can contribute to the skilled person’s expectation of success

- The claimed therapeutic belongs to a class of compounds known to be effective in the treatment of the disease (T 239/16 Reasons 6.5)

- The art contains no indication that the claimed therapeutic would behave differently to other compounds from the same class which are known to be effective in the treatment of the disease (T239/16 Reasons 6.5)

- A suitable animal model for the disease exists and the claimed therapeutic has been tested in that animal model (T239/16 Reasons 6.6)

Factors which can diminish the skilled person’s expectation of success

- The claimed therapeutic has a chemical structure and/or belongs to a class of compounds that is dissimilar to those known to treat the disease (T 715/03 Reasons 2.4.3, T 239/16 Reasons 6.6)

- There is no suitable animal model for the disease (T715/03 Reasons 2.2)

- The disease is a complex disorder for which an animal model does not exist and there is an express indication in the art that conclusions as to tolerability and/or efficacy must await the results of the clinical studies (T 715/03 Reasons 2.2)

- Lack of data based on in vitro or in vivo experiments (T 33/19 Reasons 20)

- Evidence relating to a lack of efficacy of the same compound in treating the same disease (T96/20 Reasons 13)

Secondary factors which may or may not influence the skilled person’s expectation of success

- No therapy for the disease has been approved for a long period of time (T 96/20, Reasons 10)

- The drug acts via a complex cascade system and the art contains reports of failed attempts to treat diseases associated with that system, but these failures pertain to different compounds and different diseases (T 96/20 Reasons 12-13)

- Clinical trial success is not certain, or the success rate is low for the disease/class of diseases (T 239/16 Reasons 6.6, T 2506/12 Reasons 3.12.2)

- The therapeutic has not yet been tested in humans (T 239/16 Reasons 6.6)

[1] See, for example, the guidance that is provided under the heading “Applications that need expert advice” found here: Clinical trials for medicines: apply for authorisation in the UK – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[2] See e.g. page 5 of the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) recommendation paper on elements required to support the medical plausibility and the assumption of significant benefit for an orphan designation (EMA/COMP/15893/2009 Final)