Mathys & Squire has been recognised in JUVE Patent‘s UK Rankings in the ‘Patent Filing’ category for the third consecutive year in the fields of ‘Pharma and biotechnology’, ‘Medical technology’, ‘Chemistry’, ‘Digital communication and computer technology’, ‘Electronics’ and ‘Mechanics, process and mechanical engineering’.

As well as a practice-wide recommendation for the firm, four of our partners have maintained their status as Recommended Individuals: Hazel Ford and Philippa Griffin (for ‘Pharma and biotechnology‘), Chris Hamer (for ‘Chemistry‘) and Jane Clark (for ‘Digital communication and computer technology‘ / ‘Mechanics, process and mechanical engineering‘).

Partner Chris Hamer has also received a specialist Leading Individual ranking again this year for his expertise in Chemistry, one of only nine UK patent attorneys noted for their technical speciality – see here.

In its third annual UK rankings since the guide launched in 2020, the JUVE Patent editorial team has conducted research on how external developments have impacted the UK patent market. Based on this research, the UK 2022 Rankings bring together the top-ranked patent lawyers, patent attorneys and barristers who are making a national and international impact.

To see the JUVE Patent UK 2022 rankings in full, please click here.

Update: 21 December 2021

In an update to the September 2021 Court of Appeal decision featured below, the Legal Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office (EPO) has, in oral proceedings held yesterday, confirmed that an inventor on patent applications must be a human being, thus dismissing appeals that an AI should be recognised as an inventor. We await the board’s written decision and reasons, which we will cover once they become available.

In a September 2021 judgment, the Court of Appeal has upheld that, within the current legal framework in the UK, an artificial intelligence (AI) machine cannot be named as the inventor in relation to a patent application for an invention which it created. The full decision is available here: Thaler v Comptroller General of Patents Trade Marks And Designs [2021] EWCA Civ 1374.

Dr Thaler applied for two UK patents in respect of inventions which he claims were created by his AI machine known as DABUS (‘Device for the autonomous bootstrapping of unified sentience’). The applications were considered withdrawn by the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) by failure to identify the inventor and how Dr Thaler derived the right to be granted a patent from the inventor in accordance with section 13 of the Patents Act 1977. Dr Thaler claimed that DABUS was the inventor and that he derived the right to be granted a patent as owner of DABUS. This was first appealed to the High Court in 2020, but was dismissed, and in turn was appealed to the Court of Appeal and came before experienced patent judges, Lord Justice Birss, Lord Justice Arnold, and Lady Justice Laing.

In essence, the court considered three main questions:

- Does DABUS qualify as an ‘inventor’ within the meaning of the Patents Act?

- Is Dr Thaler entitled to apply for a patent in respect of inventions made by DABUS?

- Was it correct that the applications were deemed withdrawn?

1. Does DABUS qualify as an ‘inventor’ within the meaning of the Patents Act?

All three judges agreed that the Patents Act makes it clear that only a person can be an ‘inventor’. The Act does not actually explicitly state this requirement, merely that the inventor is the actual deviser of the invention. Lord Justice Arnold explained that the Act nevertheless implies that the inventor must be a person, supported, for instance, by the dictionary definition of a deviser being ‘a person who devises’. Other indications can be found in the Act, such as section 13(2) which imposes a requirement on the applicant to identify the person whom they believe to be the inventor. In addition, section 13(1) states the inventor has a right to be mentioned as the inventor in a patent – and only a person can have such a right. Moreover, section 7(2) states that a patent may be granted: (a) primarily to the inventor, (b) to any person who is entitled by an agreement or rule of law, or (c) to the successor in title of either (a) or (b) (e.g. to whom the rights have been assigned), but to no other person. Because this is an exhaustive list, it seemingly follows that the inventor must be a person. Therefore, the judges were in agreement that an inventor can only be a person – and DABUS is clearly not a person.

In answer to question (1): No, because an inventor must be a person.

2. Is Dr Thaler entitled to apply for a patent in respect of inventions made by DABUS?

As set out above, section 7(2) provides that a patent can be granted to someone who is not the inventor if they are entitled by virtue of an agreement or a rule of law. Such a rule of law may include the UK legal mechanism that inventions devised by employees will broadly be owned by their employers. Dr Thaler claimed that he had derived the right to be granted a patent by rule of law as the owner of DABUS. This was seemingly based on a principle in property law, where the owner of pre-existing property owns the new property resulting from it (such as the fruit which is produced from a tree). However, Lord Justice Arnold held that this principle did not apply to intangible property such as intellectual property rights like the right to be granted a patent. An example was provided to contrast the fruit tree analogy, where, if person A took a digital photograph using person B’s camera, although person B owned the camera (the original property), person A may own copyright in the photograph and not person B (the new intangible property). Similarly, intangible property such as the right to be granted a patent for an invention resulting from an AI machine would not automatically flow to the owner of the machine. Accordingly, Lord Justice Arnold held that there is no rule of law that would enable Dr Thaler to possess the right to apply for the patent, and therefore he cannot be entitled.

In answer to question (2): Dr Thaler cannot be entitled.

3. Was it correct that the applications were deemed withdrawn?

According to Lord Justice Arnold, it logically follows that, because (i) DABUS is not a person and cannot be an inventor, and (ii) Dr Thaler was not entitled to apply for the patents, Dr Thaler had failed to identify the person whom he believed to be the inventor, and had also failed to provide an indication of how he derived the right to be granted a patent.

It is worth noting that Lord Justice Birss, also a very experienced patent judge, dissented from this judgment and found that, although DABUS was not a person so could not be an inventor, simply because Dr Thaler had filed a statement identifying whom he believed to be the inventor and indicating the derivation of his right to be granted the patent, he had satisfied the requirements necessary. He considered that it is not the function of the UKIPO to substantively examine whether the statement is correct – instead, since the statement honestly reflects Dr Thaler’s belief, it satisfies the statutory requirements. Lord Justice Birss considered that this fulfilled Dr Thaler’s obligations under section 13(2) and the applications should not have been withdrawn.

However, Lord Justice Arnold and Lady Justice Laing did not agree, finding that, although the factual accuracy of the statement does not need to be considered, the UKIPO is entitled to deem the application withdrawn if it clearly does not fulfil the statutory requirements. For example, it was a statutory requirement that the applicant identify the person who he believes to be the inventor, not merely their belief about who the inventor is. In these judges’ view, it was clear that the statements filed did not comply with the legislation because Dr Thaler did not identify a person as the inventor and did not identify a valid legal mechanism for deriving the rights. As a matter of law, and not as a matter of fact, the UKIPO can identify that the statements are defective, and that the requirements have not been met.

Accordingly, on a 2-1 majority, the Court found that the applications were correctly deemed withdrawn, and the appeal was dismissed.

In answer to question (3): the applications were correctly deemed withdrawn.

Comments

The fact that such an experienced patent judge as Lord Justice Birss would have found in favour of Dr Thaler indicates how the concept of AI inventorship is not clear-cut. It must be said that, following this judgment, it appears quite clear that, under current UK law, there is no room for an AI machine to be named as an inventor of a patent. It is worth noting that this decision referenced submissions which relied on where the law ought to be, and not where it is, and from the judges’ comments it is evident that, whether or not an AI machine should be identified as an inventor for a patent, a legislative change is required in order for AI machines to be allowed within the definition of inventor within the Act – and the judges are constrained in this decision by what the law currently is.

This judgment appears logical in that DABUS should not be an inventor because it is obviously not a person (whether a natural person, such as a human, or even a legal person for that matter, such as a corporation). As the inventor cannot have any rights, it follows that there are no rights which can be transferred to the owner of the machine, whether a legal mechanism exists or not. Furthermore, ownership of the machine appears to be a rather arbitrary mechanism to obtain rights from the machine (if such rights could exist). This would raise questions of what would happen if ownership of the machine was transferred, especially with respect to when the invention was devised by the AI machine.

If an AI machine cannot be named as inventor on a patent, in the absence of a change in legislation or at least until the time of any such change, applicants will have to determine how to apply for patents which are created by such AI. This raises the question of whether the owner of the AI could validly be named as the inventor, or whether it is the person developing or creating the AI; training the AI with data; setting the specific technical problem the AI has solved; or even identifying the inventive step of the invention created by the AI. In the UK at least, there is an argument that if the applicant identifies the person that they truly believe to be the inventor (whether that is the owner of the AI or otherwise), the requirements of section 13 are satisfied. This could only be questioned by someone who contests that they are instead entitled to the grant of the patent.

Looking forward, the UKIPO has since commenced a consultation on AI with respect to intellectual property rights. The outcome of this could well be the first step towards a solution to a problem that was likely not envisaged when Parliament decided on the wording of the Patents Act over 40 years ago.

The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) consisted of 12 days of discussions and debates between climate activists, governmental representatives, and politicians. As per the Paris Agreement, the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius has been high on the agenda, with this year’s summit working to transition this from a mere target to an actionable plan. A few weeks on from the COP26 summit in Glasgow, we take a look at some of the agreements.

The topic of clean technologies has been consistently mentioned throughout the summit and has encouraged over 40 world leaders to sign and commit to the ‘Glasgow Breakthroughs’ and the Glasgow Climate Pact. The overall goal of the initiative is to strengthen climate action and speed up the development of clean technologies, allowing the signatories to meet the 2030 targets and 2050 net zero goal.

The ‘Glasgow Breakthroughs’

This set of leader-led commitments aims to accelerate innovation and the deployment of clean technologies in five sectors: power, road transport, steel, hydrogen and agriculture, with a target deadline of 2030. The specific aims include:

Power: To make clean power the most affordable and reliable option to all countries to meet their power needs efficiently by 2030. Despite the official target only being set in November 2021, many companies have already been working on inventions to help implement clean power across the world. For example, OXTO Energy, as mentioned in our earlier COP26 article, has developed flywheel batteries for stabilising the intermittent supply of energy from renewable sources such as wind and solar.

Hydrogen: To make affordable, renewable and low carbon hydrogen globally available by 2030. There are already such initiatives and inventions in place to achieve this goal, Including the work of Enapter, which develops technology to turn renewable electricity into emission-free green hydrogen gas.

Road transport: To make zero-emission vehicles the new normal by making them accessible, affordable and sustainable in all regions. There has already been a shift in this area, with many car brands developing and producing carbon neutral vehicles.

Agriculture: To make climate smart and sustainable agriculture the most attractive and widely adopted option for farmers everywhere by 2030.

Steel: To make near-zero emission steel the preferred choice in global markets, with efficient use and production established in every region by 2030.

Most signatories have already made some progress in the five sectors mentioned above as part of their attempts to meet the Paris Agreement targets and net zero goal by 2050. The ‘Glasgow Breakthroughs’ will contribute to the success of all international climate change plans through a range of international initiatives to drive innovation and scale up the green industry. The commitment – and ideally completion – of these breakthroughs over the next eight years will place signatories on track to reaching all other long-term climate change tackling plans.

Glasgow Climate Pact

Alongside the ‘Glasgow Breakthroughs’, world leaders have signed the Glasgow Climate Pact, with a common theme of technology transfer and its role in the mitigation of, and adaption to, the adverse effects of climate change. The Standing Committee on Patents at WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organisation) has considered the role of patents in the effective transfer of technology and found that the “fundamental elements of the patent system play an important role in the dissemination of knowledge and the transfer of technology”. The ability of the patent system to crystalise a technological development or invention makes it the ideal vehicle to transfer technology internationally. The patent system is also well placed to reconcile the interests of the technology-rich parties and the requirements of those looking to benefit, by balancing a limited monopoly with sufficient disclosure.

Aside from the ‘Glasgow Breakthroughs’ and the Glasgow Climate Pact being signed, COP26 delegates have also addressed the global net zero target by mid-century, producing measurable goals to protect communities and habitats most impacted by adverse effects of climate change, through raising $100 billion every year and finalising the implementation rules for the Paris Agreement. The effects of the summit are set to impact the next few decades and shape the future of the green economy; we wait with anticipation to see these proposals materialise.

In a judgment by the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC) earlier this year, [2021] EWHC 1007 (IPEC) (Claydon), an important question regarding the issue of whether testing a prototype on private property can constitute a prior disclosure was addressed. This decision has important ramifications for how much precaution an inventor must take when conducting tests, especially in sectors involving large commercial equipment. At first glance, this decision seems to run counter to the earlier Court of Appeal decision in [2019] EWHC 991 (Pat) (Hozelock) which had similar circumstances. However, an important distinction is revealed when examining the facts of the two cases.

Hozelock – 17 April 2019

In Hozelock, the invention in question was an expandable garden hose, that the inventor had developed in his garden which was visible from a nearby road. An important point of contention in this case was whether the inventor’s actions amounted to a public disclosure which rendered the patent obvious.

The judge drew a distinction between the scenario where the public is given access to information, in whatever form, but no one takes up the opportunity to look at it, versus the present scenario of Hozelock, where no member of the public could have got access to the information.

The reason no one could have accessed the information is because it was held that if a member of the public had tried to observe the inventor in his garden, the inventor would have simply ceased his activity and concealed the prototypes. This distinction allowed the judge to reach his conclusion that no public disclosure had been made by the inventor in his garden.

Claydon – 22 April 2021

Whilst the Hozelock case concerned a garden hose invention, Claydon involved a tractor pulling a seed drill. This difference in magnitude between the inventions was key to how the decision was made.

In Claydon, the inventor tested the prototype in his farm before filing for the patent. There was a six-foot tall hedge surrounding his farm but it had several gaps, through which anyone could look and take note of his invention. The claimant contended that the prototype could have been seen by anyone from the public footpath, thus gaining enough information to understand the invention.

In his witness statement, the inventor said that he had previous experience of patents and had learned the hard way that public disclosure of his invention would jeopardise the chances of getting a patent granted. With this in mind, he assumed he could prevent anyone who was nearby from seeing it, by simply driving away.

In cross-examination, it emerged that the point of public access from which an observer would have been best placed to witness the testing of the prototype was a point on the public footpath. According to the inventor, the path was very rarely used in 2002, however this statement still implied that the public had access to it.

It was observed in this case that there is clearly a difference between quickly and effortlessly concealing a garden hose in a container versus driving a conspicuous vehicle away from someone whilst on a large flat field. Also of note was the fact that, even if the vehicle had driven away too far for someone to observe, it would have still left behind ‘tines’ in the field which would have given insight into how the seed drill worked.

As it turns out, no one saw the inventor’s prototype. Unfortunately for him, in both UK and European patent law, the standard is not whether the prototype was actually seen, but whether it was made available to the public.

The judge found that a skilled person, standing on the public footpath, would have been able to see the prototype in action and been able to deduce from its appearance and from the appearance of soil left in its wake, features of construction of the prototype. Further, the judge did not believe that the inventor could have feasibly taken action that would have prevented the skilled person from seeing or inferring each of those features, including the alignment of the tines. Therefore, the patent was found invalid because of prior public disclosure.

Practical and legal implications

Both of the aforementioned cases involved a prototype invention being tested by the inventor on private property that was within viewing distance of public property. What ultimately led to the different decisions for these cases was the fact that, in the Hozelock case, the invention in question was small and portable, so in theory, could have easily been concealed if a member of the public was observing the inventor during testing. In the Claydon case however, the invention was large, not portable and was situated in a wide open area and in theory, if a member of the public began to observe the inventor testing the invention, the inventor would not have been able to realistically do anything to effectively conceal what they were doing.

This decision raises the practical question of how inventors can confidentially test and develop large inventions outdoors at their own premises. One may even go as far as claiming that this would contravene the principle of non-discrimination based on the field of technology under Article 27 TRIPS, which states that:

“[…] patents shall be available and patent rights enjoyable without discrimination as to the […] field of technology […]”

In other words, inventions incorporated in larger products might de facto be discriminated vis-à-vis inventions related to smaller ones as there is uncertainty as to whether a large invention can be tested in the field without risking loss of novelty. It seems that this decision falls within the definition of de facto discrimination as, whilst the ruling appears neutral, as it is not formally addressed to a particular field of technology, its actual effect is to impose negative consequences on inventors within industries which require large scale tests. For some this finding is likely to be considered unfair and difficult to justify.

Data provided by Mathys & Squire has been featured in an article published by City A.M. which highlights a 59% rise in global patents for electric vehicle (EV) technology filed with the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) in the last year, compared to filings five years ago.

An extended version of the article is available below, which has also been published by The Scotsman, Renewable Energy Magazine and The Patent Lawyer.

Global patent filings for electric vehicles are rising, while those for petrol and diesel vehicles are falling rapidly as the 2030 deadline for the end of carbon-emitting car sales gets closer.

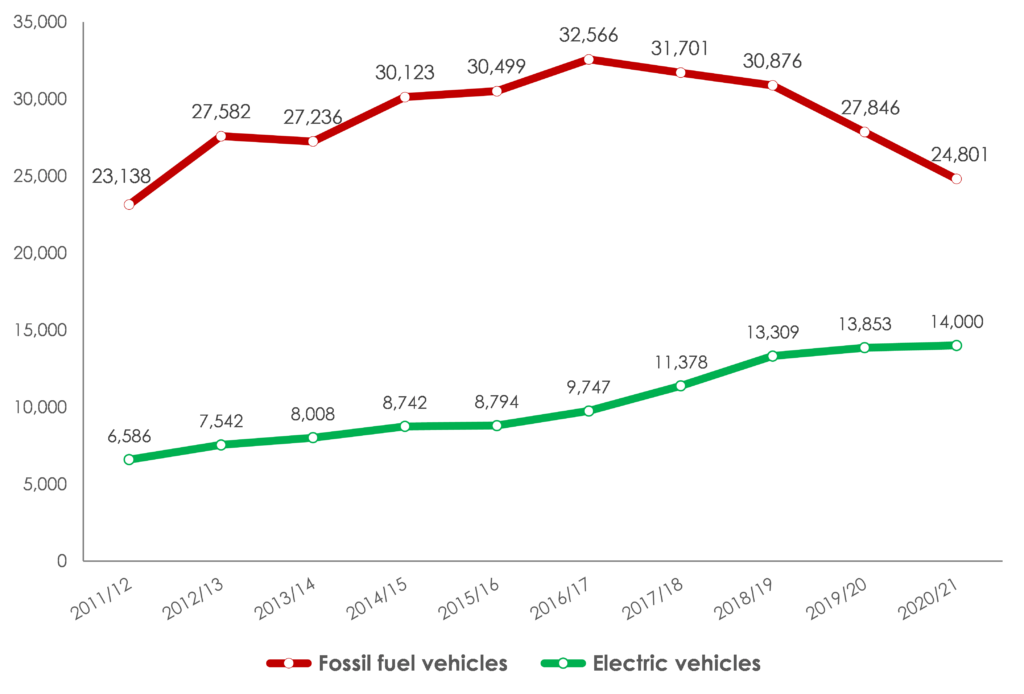

14,000 global patents for electric vehicle technology were filed with WIPO in the last year*, an increase of 59% on the 8,794 filed five years earlier. In contrast, the number of patents for fossil fuel vehicles has fallen to 24,801 in the past year, a decline of 19% on the 30,499 filed five years ago (see graph below).

The figures show that there remains much to play for in the electric car industry. The rise in global patents filed for electric vehicles has been much more gradual, increasing by just 4% and 1% in the last two years.

Sean Leach, partner at Mathys & Squire, says that much innovation is yet to be done to bring truly affordable electric cars to all consumers, as manufacturers must do over the next decade. The cheapest new electric car** available in the UK is currently priced at £19,795, compared to £7,995 for the cheapest new petrol car.

He adds that it will be interesting to see whether patent filings for fossil fuel vehicles fall more quickly as more countries and cities put in place challenging deadlines for the end of new petrol and diesel car sales. The UK, Germany, India, Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden are among the countries that have committed to a deadline of 2030, while the US, Japan, South Korea and Canada have 2035 deadlines.

Sean Leach says: “Electric vehicle innovation has picked up some speed but not as much as many would have hoped.”

“There is still a great deal of research to be done to make choosing an electric car an easy choice for every consumer. Prices are still too high for many people and that simply must change by 2030. Manufacturers are competing to deliver an electric car that sells in the £10,000 range. That will require a great deal of R&D.”

“With the end of new fossil fuel cars now less than a decade away in a number of major economies, some will be surprised to see patents for petrol and diesel vehicles only starting to fall more sharply in the past two years. The product development cycle is long in the automotive industry and it is still going to take some time for a few carmakers to really pivot to electric vehicles.”

US leads the way for electric vehicle patents

Organisations in the US were the most prolific filers of global patents related to electric vehicles last year. Data shows that the US registered 49% of all global EV patents at WIPO (6,827 patents in 2020/21). By these same measures, Chinese filers are the second most prolific, filing 28% of all global electric vehicle patents in 2020/21 (3,901 patents).

The US has long been a hotbed of electric vehicle innovation, with Tesla and businesses in its supply chain playing a key role in commercialising fully-electric cars.

The UK saw a comparatively tiny number, with data showing as few as 65 patents for electric vehicle technology were filed in 2020/21. This makes up only 0.4% of all filings in the category at WIPO. The list of leading UK filers is dominated by lithium-ion battery development businesses, and the Government is hoping to increase UK innovation in this area through the UK Battery Industrialisation Centre in Coventry, which opened in July 2021.

Adds Sean Leach: “This picture is worrying, but statistics alone don’t tell the whole story. UK engineering experts and entrepreneurs are already making the UK a hub for electric vehicle development. The UK Battery Industrialisation Centre is a significant step forward in that regard, but once it has been developed, new technology must be protected if it is going to provide real value to business over the long term.”

“We hope to see the number of EV patents from UK filers rise – there are some very innovative UK businesses in the battery supply chain in this country, and they need to keep pace with their German, US and Chinese counterparts.”

Carmakers begin to move away from petrol and diesel car research – number of patents for fossil fuel vehicles down 20% in two years

* year end 30 June 2021

** excluding two-seater cars and quadricycles

The UK Government announced the start of a call for views on standard essential patents (SEPs) on 7 December 2021.

In brief, the consultation is designed to seek opinions on the issues SEPs raise in relation to market functionality and the balance the current system strikes for industry and innovators, as well as SEP rights holders. The responses will help the UK Government assess whether intervention is required to optimise the UK intellectual property (IP) framework with the aim to promote innovation and competition.

Why is this consultation happening?

A rise in the use of wireless technologies (3G, 4G and 5G), coupled with increasing globalisation of commerce and a need for interoperability, has resulted in the increasing importance of technical standards. This call for views on SEPs forms part of the UK Innovation Strategy published in July earlier this year which sets out the Government’s long-term plan for delivering innovation-led growth.

The consultation also comes in response to the Government’s Telecoms Diversification Strategy where SEPs were identified by the Diversification Taskforce as a potential barrier to diversification of the telecoms landscape. This call for views therefore aims to establish whether government intervention is required and seeks evidence to better understand what the intervention could look like to improve market functioning and promote innovation within the SEP system.

What will the consultation focus on?

The call for views focuses on four specific areas:

- The relationship between SEPs, innovation and competition – in particular, how the SEP ecosystem can support competition and innovation and benefit UK consumers.

- The functioning of the market and competition, including whether the current SEP system creates barriers to innovators.

- The amount of transparency surrounding the SEPs system, including in pricing negotiations.

- The functioning of the patent system and SEP licensing framework, and role of the courts in SEP licensing disputes.

Responding to the consultation

The call for views will run for 12 weeks – opening from 7 December 2021 and closing at 11:45pm on 1 March 2022.

Respondents must submit a completed response form available online to [email protected]. The form sets out 27 questions further breaking down the four key areas described above.

What happens after 1 March 2022?

After the deadline, the UK Government will consider the responses and we can expect the publication of a formal report summary in due course. The call for views states that the information obtained will inform government’s decision on any potential intervention that is required within the SEP ecosystem.

We are pleased to see the attention the UK Government is dedicating to promoting innovation and creativity within the UK using IP frameworks. If any clients or contacts have views on any of the questions the consultation seeks answers on, we would be happy to hear their thoughts.

Good things come to those who wait. After years of seemingly little to no progress and challenging negotiations, and with the Unitary Patent (UP) being on the verge of introduction several times, the time has finally come. Despite many hurdles, unforeseen detours, and some political headwind, the way now seems clear for the UP.

The Unitary Patent and the Unified Patent Court (UPC) seemed set to be on the verge of introduction a few years ago. However, various political imponderables such as Brexit – with the subsequent exit of the UK from the EU and thus also the UP and the UPC – as well as legal hurdles such as the lawsuits against ratification of the UPC before the German Federal Constitutional Court, have delayed its implementation. In July 2021, the long-awaited decision of the Federal Constitutional Court removed the last obstacle to said ratification. Despite federal elections taking place the same year, Germany swiftly ratified, so that the three required states with the highest number of European patents filed – France, Italy and Germany – had thus taken the decisive step towards the UPC and the UP coming into effect. After a range of further national ratifications, the final required national decision is now awaited for 2 December 2021 with the ratification of the UPC being on the agenda of the Austrian Federal Council.

With the political hurdles regarding the ratification process thus overcome, implementation of the UPC and the connected UP can finally commence. However, the main effort still lies ahead: administrative structures now have to be created and the required staff must be hired and trained.

Patent owners will now be able, and are in fact required, to do their part as well, as far as considerations and decisions are concerned. Even if the actual UPC start date is not likely before 1 January 2023, the likely advantages and risks of the new system are already known. As the UP is closely interlinked with existing European patent law in terms of its structure, it is advisable for patent owners to take a closer look at this linkage and to consider its effect on existing patent portfolios as well as on the future filing strategy in more detail.

Due to the multitude of possible patent uses, as well as varied market and competitor scenarios, no general recommendation can be made regarding UPC opportunities and risks. Rather, a detailed analysis of the individual business’ entire IP situation is required. This is the only way to ensure that patent owners are fully prepared prior to the introduction of the UP, both with a view to their portfolio and comprehensive overall strategy. This can range from active use of the UP; to a ‘wait-and-see’ approach while requesting to opt-out; to possible avoidance strategies through national applications. Regardless of the approach, at least there is now some clarity around the long-delayed start of the UPC so that patent owners can get prepared.

Click here to read the above article in German.

Following the order issued on 16 July 2021, the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBA) has now published its full written Decision in G 1/21. The procedural objections raised throughout the earlier part of the proceedings have been covered in a previous article, and so this article focuses on the opinion of the EBA on the status of oral proceedings by videoconference in the context of the European Patent Convention (EPC).

Although the EBA considered it necessary to restrict the referred question to proceedings before the Boards of Appeal, as opposed to departments of first instance, the Decision issued provides general guidance with respect to the circumstances under which oral proceedings by videoconference may be imposed on parties without their consent. The EBA acknowledged that in-person proceedings should be the ‘gold standard’ default, with videoconferencing able to provide a suitable alternative in some cases. The EBA also commented that the parties’ preferences (with good reason) should be given due consideration by a Board when deciding on the format of oral proceedings. Thus it seems that we can expect a return to the ‘old normal’, at least for Board of Appeal proceedings, following the current pandemic.

Scope of the referral

The EBA opened by reformulating the referred question in view of the particular need for clarification in the referring decision (CLBA 2019, V.B.2.3.3). In doing so, they considered that the choice facing the referring Board in T 1807/15 was not between in-person and videoconference, but instead between videoconference and postponement – the question was thus limited to periods of ‘general emergency’, such as the Covid-19 pandemic. However, the EBA has not provided further comment as to which parties able to declare a ‘general emergency’ (or when it is over).

The EBA did consider it appropriate to evaluate compatibility of videoconferencing with the EPC more generally, and not solely in regard to Article 116 EPC, as “the right to oral proceedings is an expression of [the right to be heard under Article 113(1) EPC]”.

Where does videoconferencing stand?

The fundamental question of what legal status is given to a videoconference may usefully be considered in several parts, summarised as follows:

(1) Do oral proceedings by videoconference constitute ‘oral proceedings’ within the meaning of Article 116 EPC?

YES

(2) Is a videoconference equivalent to in-person oral proceedings?

NO

(3) Is a videoconference a suitable format for conducting oral proceedings?

YES

The first of these questions focuses on the interpretation of Article 116 EPC, which is actually concerned with when oral proceedings are to take place, rather than what constitutes ‘oral proceedings’. The EBA considered the term ‘oral proceedings’ to be very general so a broad interpretation, requiring only verbal communication between parties, was adopted. However, it was later noted that a telephone interview would not be ‘suitable’ in the context of the third question. In dismissing allegations about the intention of the legislators of the EPC 1973 and 2000, the EBA stated that the purpose of the Convention is to “provide a system for the grant of European patents with the aim of supporting innovation and technological progress”, and therefore considered that it would be at odds with the fundamental object and purpose of the EPC to exclude the use of newer technologies in the conduct of oral proceedings. It was also pointed out that the use of laptops, PowerPoint presentations, and digital whiteboards would equally not have been envisaged by the original legislators, but these forms of technology have nevertheless formed a useful part of oral proceedings for some time.

On this topic, the Decision makes an interesting point that, if videoconferences were not ‘oral proceedings’ within the meaning of Article 116 EPC, the validity of certain aspects of such videoconferences even with the consent of the parties could be called into question. For example, giving parties the opportunity to make oral requests (in accordance with their right to be heard), or the rendering of an oral decision by a Board, might have different legal status as compared with the same procedural acts performed in-person.

The second and third questions were considered under the same heading in the Decision, but there seems to be an important distinction between them. Specifically, the second question appears to relate to the effectiveness of videoconferencing in general, whereas the third assesses simply whether it meets the needs of users of the European patent system where necessary, e.g. to avoid postponement of oral proceedings in the height of a pandemic. It is noteworthy that the EBA agreed (at least with a number of the amicus curiae briefs) that communication by videoconference “cannot, at least for the time being, be put on the same level as communicating in person”, i.e. it is not equivalent to in-person proceedings. However, the EBA considered that the essential features of oral proceedings can be ensured by a videoconference, namely (as set out in R 3/10) “.. to allow each party to make an oral presentation of its arguments, to allow the Board to ask questions, to allow the parties to respond to such questions and to allow the Board and the parties to discuss issues, including controversial and perhaps crucial issues”. This is consistent with the analysis above with respect to the legal validity of acts performed via a videoconference. The EBA also noted that the extent to which body language can be interpreted (which was a feature of a number of the submissions by those taking a position against videoconferencing, including the appellant) is a matter of degree; the point was made that interpretation of body language could equally be impacted by distance or layout in a physical courtroom.

Thus, the Decision concludes that videoconferencing does provide a suitable alternative to in-person proceedings.

In what circumstances may a party’s request for in-person oral proceedings be denied?

Before turning to this final part of the question, the Enlarged Board noted that oral proceedings are most often held on the request of a party. It was therefore concluded that the choice of format for oral proceedings should be made by the party requesting them, particularly as they could have good reasons to prefer in-person proceedings (since it has been established that these are the ‘gold standard’).

Despite this conclusion, it was considered that the Board of Appeal could overrule the party’s preference in format under certain circumstances. The conditions for doing so as set out in the Decision are that:

(i) there must be a suitable, if not equivalent, alternative (such as videoconferencing); and

ii) there must be circumstances specific to the case which justify the decision not to hold the oral proceedings in person.

The EBA specified that the decision as to whether the specific circumstances justify deviating from a party’s wishes “must be a discretionary decision of the Board of Appeal summoning them”.

Whilst the present Decision may have addressed the issues raised in light of T 1807/15, it remains to be seen how the Boards of Appeal will apply the guidance and to what extent they will exercise their discretion. The Decision does feature statements with which we are now all too familiar, including ‘general travel restrictions’, ‘quarantine obligations’, and ‘other health-related measures’ preventing travel to an in-person hearing, and so there is the potential for some variation in the interpretation of these deciding factors. One helpful point, although seemingly less relevant after over a year of trialling videoconferencing in European Patent Office (EPO) proceedings, is that the decision should not be influenced by administrative issues including the availability of rooms and interpretation, or by intended efficiency gains.

Conclusion

Whilst we might still expect some discussion in the coming months about the suitability of videoconferencing as an alternative to the ‘gold standard’ of in-person hearings in particular cases, the overall impression based on the reasoning of the present Decision is that the EBA envisages the EPO maintaining the status quo for the time being (at least until an end date to the most recent state of ‘general emergency’ is announced). Nevertheless, the Decision has now provided particular terms as a springboard to open discussion with the Boards of Appeal surrounding parties’ particular circumstances, and it will be interesting to see how broadly or narrowly these terms are applied in the coming months, including whether the departments of first instance look to follow the same procedure.

For the moment, it seems that we can conclude that the EBA does not see videoconferencing becoming a ‘new normal’ in its current form, and we hope to see a return to the premises of the EPO for those of us who are keen to do so.

The UK Government officially launched its consultation on intellectual property (IP) and artificial intelligence (AI) on 29 October 2021, as part of the National AI Strategy (see our summary here) which aims to ensure the UK continues to be a world-leader in AI development and deployment.

In brief, the consultation is designed to seek opinions on the issues surrounding IP – in particular copyright and patents – and AI as a tool for innovation and creation. The responses will help the UK Government to design and implement solutions that will tackle these issues and pave the way through our increasingly AI-driven world.

Why is this consultation happening?

This consultation follows the earlier call for views on AI and IP, a response to which was published in March 2021, in which a number of questions were raised regarding the role of copyright and patents to protect inventions and creative works arising from AI.

For example, there was concern that copyright can restrict the development of AI by limiting what sources can be used for developing or training AI. In addition, issues were identified with the patent system that may also act as a barrier to AI innovation or use.

There is also the ongoing debate over whether IP rights can or should be used to protect inventions and creative works partly or wholly arising from AI, and how or to what extent this protection occurs.

What will the consultation focus on?

The consultation therefore focuses on three specific areas to understand these issues in more detail:

- Copyright protection for computer-generated works without a human author. These are currently protected in the UK for 50 years, but the question is: should they be protected at all, and if so, how?

- Licensing or exceptions to copyright for text and data mining, which is often significant in AI use and development.

- Patent protection for AI-devised inventions: should we protect them, and if so, how?

What does the UK Government hope to achieve?

The ambition behind the consultation is to ‘encourage innovation in AI technology and promote its use for the public good’. In addition, the consultation aims to ‘preserve the central role of IP in promoting human creativity’.

Similarly, the UK Government have emphasised that any new measures implemented as a result of the consultation must also meet these goals and be based on the best available economic evidence.

Responding to the consultation

The consultation will run for 10 weeks – it began on 29 October 2021 and will close at 11.45pm on 7 January 2022. Responses must be submitted via a completed response form, available online, to a specially created email address. The form is split into two main sections; one requests information from the responder, and one sets out 21 questions further breaking down the three key areas described above.

What happens after 7 January 2022?

Following the consultation, the UK Government will consider the responses and publish a formal response document in due course. The consultation states that the information obtained will be used to inform government decisions on any changes to legislation that appear necessary as a result and will help to achieve the aims of encouraging AI innovation and implementation, whilst still promoting and protecting human creativity.

The UK Government have also published an Impact Assessment, which provides further information about the consultation and indicates there are no preferred options at this consultation stage. It will be interesting to see whether there is a consensus preferred option from the responses to the consultation, and how the UK Government takes the findings into consideration going forwards.

We are pleased to see the attention the UK Government is dedicating to the role of IP in AI and if any clients or contacts have views on any of the questions the consultation seeks answers on, we would be happy to hear their thoughts.

Thanks to technological advancements and innovation driving change at an increasing rate, business owners are realising that intangible assets and registered rights such as intellectual property (IP) contribute significantly to overall business value. This has therefore sparked the need to understand the value of IP, but – as with all intangible assets – can often be challenging. Mathys & Squire Consulting provides clients with insights into the IP valuation process and a clear understanding of the components of value, as outlined below. Although the valuing of IP can be complex, it is an essential stage to prioritise before engaging in any IP transactions.

A crucial consideration in IP valuation is to understand your business model and to evaluate whether it is most likely to lead to a transaction within reasonable timescales, with a party that has a key position in a strong value chain. It can often be the case that several business model alternatives exist, and numerous factors need to be reviewed to determine the optimum approach to take when valuing IP.

Another aspect to consider is awareness of the assets’ ownership within the value chain (i.e. owned by the customer or sub-contractor). At every step of the value chain, the value of an intangible asset tends to increase, and thus transactions at different levels can yield significantly differing results – both in terms of the level of success of the transaction itself and the ultimate financial outcome.

A further consideration is the reason behind IP valuation in the first place, which could be for the purpose of mergers and acquisitions; securing more funding and investments; asset transfers; infringement-related damage evaluation; or insolvency. All these scenarios call for an IP valuation, but it is likely they will be approached differently. It is therefore crucial to understand the reason for valuation, as it will help determine the most suitable calculation method. Certain circumstances may require a more pragmatic approach than others, and IP valuation should cater to all cases, with the overriding consideration that the IP valuation model is designed to support transaction negotiations.

The flexibility built into the IP valuation process can provide a portfolio’s value at a particular time and market strength. The value of intangible assets and an IP portfolio can fluctuate significantly given changes to the state of the economy, industry trends and market competitiveness. Such valuation should be updated as the business expands or any external changes occur, which could inflate or devalue the asset value.

The industry in which your business operates also has a significant impact on asset valuation. Different industries have varied product development turnaround time, with some being able to market an invention or technology in less than two years, while others may take 15 years to do so. This can directly influence the value of assets in terms of the time to market and market growth. Certain markets also have regulations and de facto standards that businesses must comply with to enter the market. For any new invention, the valuation model needs to take account of ongoing investment required to demonstrate regulatory compliance.

The market context and purpose of intangible asset and IP valuation are key factors in establishing a negotiation position, leading to a successful transaction. Mathys & Squire Consulting has developed a methodology that can be used to enable clients to understand where the key value drivers are within a transaction, which leads to meaningful and efficient negotiations.