When we think of music, we think of melodies, lyrics, rhythms, and genres that define eras and shape culture. From Britpop and Post-Punk to Drum and Bass and Grime, musical expression has continually evolved over previous centuries. But behind the sound lies a parallel story of innovation: the development of the tools and technologies that shape how music comes to life and reaches its audience.

The crescendo of musical patents

From synthesizers to streaming platforms, technological breakthroughs have revolutionised the music landscape. At the heart of this transformation is intellectual property, as patents protect the innovations that drive the music industry forward. What began with relatively simple mechanical inventions has grown into a diverse and rapidly expanding field, reflecting the pace of technological progress in how music is composed, performed, recorded, shared and experienced.

In this article, Associate Clare Pratt highlights a selection of intriguing and pioneering music patents which illustrate the breadth of innovation within the industry.

Instrumental Inventions

In the 19th century, as renowned composers penned melodies still celebrated today, inventors were crafting the instruments that would become fundamental to creating music. Among them was Belgian instrument maker Adolphe Sax. In 1846, he patented a woodwind instrument with a tapered barrel that combined the projection of brass with the agility of woodwinds. He called it the saxophone.

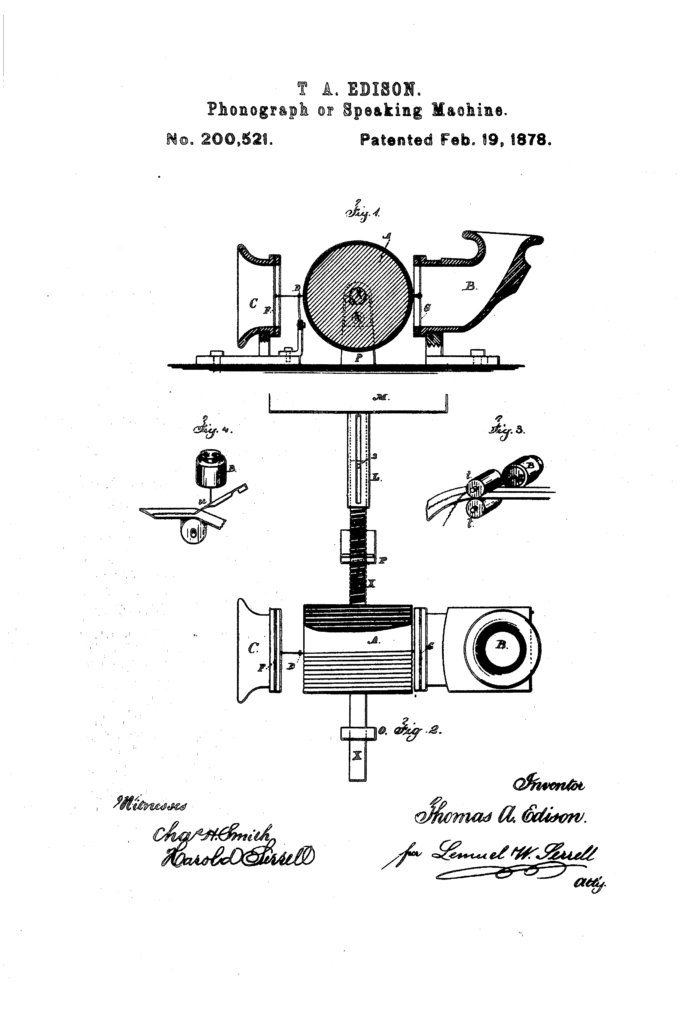

A few decades later, Thomas Edison created the first device capable of recording and reproducing sound, named the phonograph. This enabled music to move from live performance into private spaces, to be enjoyed wherever and whenever. The American inventor patented the phonograph in 1878. Seeking improvements to the phonograph and the graphophone, which Chichester A. Bell and Charles S. Tainter developed, Emile Berliner introduced the flat disc format. In 1887, he patented the gramophone which offered a more practical alternative.

Technological breakthroughs continued into the 20th century. A key moment came in 1932 with the granting of U.S. Patent No. 1,885,001 to H.F. Olson for an “apparatus for converting sound vibrations into electric variations.” This patent marked a pivotal step in the development of the modern microphone.

Together in Electric Dreams

Although experiments with electrically powered instruments date back to the 18th century, it was the widespread adoption of electronics in the late 1900s that truly redefined music. Innovations such as electric guitars and synthesizers fuelled the emergence of entirely new genres, such as rock, disco, and techno, while amplified sound systems allowed musicians to perform in front of huge crowds.

One of the earliest and most influential patents came in 1937, when George Beauchamp secured protection for an “electrical stringed musical instrument”, the first commercially marketed electric guitar. This paved the way for the modern electric guitar. Another pioneer in electric guitars was Ted McCarty, who, as president of Gibson, played a pivotal role in advancing electric guitar design. He oversaw the development of Gibson’s first solid-body models and patented innovations like the “Tune-O-Matic” bridge in 1956, which became a standard feature on Gibson models, and one of his unique guitar designs in 1958.

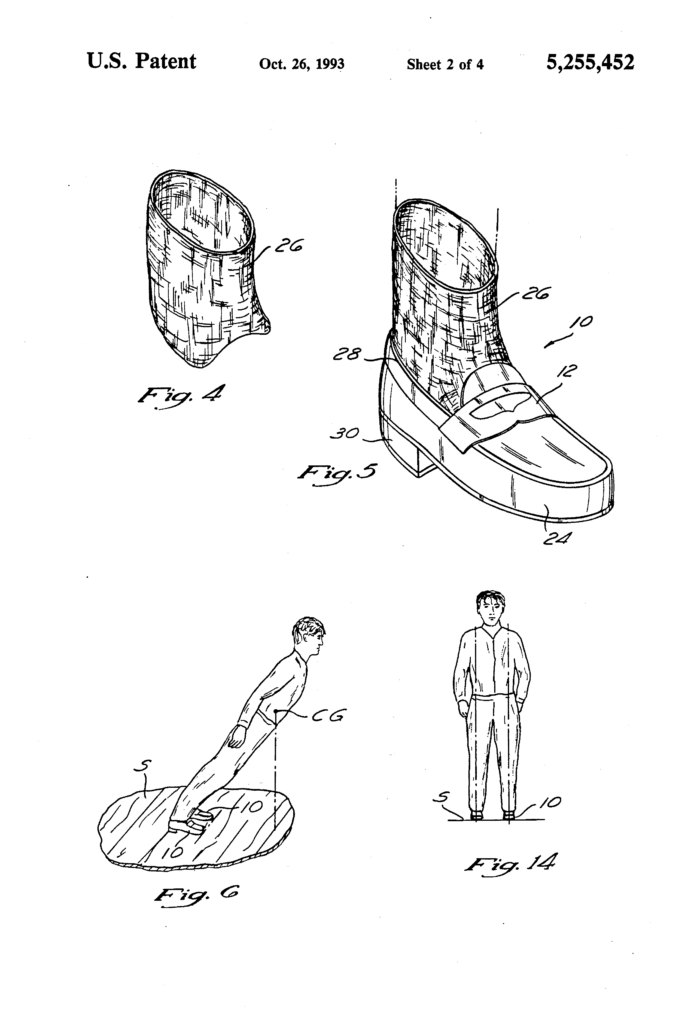

In addition, some of the most creative contributions to music technology have come from artists themselves. Guitar legend Eddie Van Halen received a patent in 1987 for a body-mounted support that allowed him to play his guitar face-up, “to create new techniques and sounds previously unknown to any player.” Similarly, Michael Jackson left his mark not only on pop music but on stagecraft. In 1993, the US Patent and Trademark Office awarded him patent for a shoe with a heel mechanism that latched onto stage pegs. The invention allowed him to lean ‘impossibly’ far forward in his iconic Smooth Criminal move, aptly titled the “Method and means for creating anti-gravity illusion.”

The Digital Turn of the Century

The late 20th and early 21st centuries ushered in a further wave of digital innovations that reshaped how music is made and experienced.

One of the most transformative (and controversial) developments was Auto-Tune. Created by geophysical engineer Andy Hildebrand, Auto-Tune applied techniques used in seismic data analysis to audio processing, enabling automatic pitch correction in real-time vocal and instrumental performances. Hildebrand’s software is protected by U.S. Patents No. 5,727,074 (“Method and apparatus for digital filtering of audio signals”, issued in 1998) and No. 5,973,252 (“Pitch detection and intonation correction apparatus and method,” issued in 1999). While initially conceived as a subtle corrective tool, Auto-Tune became a defining effect in its own right, famously debuting in Cher’s 1998 hit Believe and later revolutionising pop, hip-hop and beyond.

Transforming how we identify music, Shazam, an audio-processor app, was developed in the early 2000s. The app can recognise songs within seconds, even in noisy environments, by comparing audio fingerprints, based on time-frequency peaks, against a vast database. Developer Avery Li-Chun Wang secured patents for the underlying technology, including a “system and methods for recognising sound and music signals in high noise and distortion” and a “method and system for content sampling and identification.”

The Future of Patents in Music

Looking ahead, the intersection of music and technology shows no signs of slowing. Emerging trends are already shaping the next frontier of musical innovation—and intellectual property will continue to play a central role in protecting and enabling this progress.

- AI is increasingly being used for musical composition, mastering and even creating virtual artists. Future patents could focus on advanced AI models that can generate complex, nuanced and stylistically coherent music. Our previous article on AI and music covers the concerns for intellectual property protection which arise with machine learning models.

- Blockchain technology offers a transparent and secure method for tracking music ownership and royalties, whilst NFTs allow artists to create, authenticate, and monetise unique digital assets.

- Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality technologies are redefining live experiences by creating immersive virtual concerts and interactive performances that blend the digital and physical worlds.

As music continues to evolve alongside technology, patents will remain crucial in protecting and encouraging the creative ingenuity that pushes the industry forward. From the early inventions of the 19th century to the digital breakthroughs of the 21st, each innovation has reshaped how we create, share, and experience music. With the rapid rise of AI, blockchain, and immersive technologies, the next era of music promises even more exciting opportunities, as well as presenting significant challenges for inventors, artists and intellectual property law.

Last week, on the 24th April, we hosted an incredible event at our London office in the Shard, a celebration marrying World IP Day, which took place on the 26th April, with our 115-year anniversary.

IP and Music: Feel the Beat of IP

As a firm committed to encouraging and protecting the expression of people’s ideas, we embraced this year’s theme for the 2025 World Intellectual Property Day campaign for our event: “IP and Music: Feel the Beat of IP.” Intellectual property underpins the very core of creativity, allowing ideas to blossom and people’s success to be sufficiently acknowledged – and music is an industry governed by creativity.

Patents are filed for innovative music tech, such as musical instruments or algorithms for generating or modifying music. Trademark registration protects branding, as applied for example to album covers or merchandise, to distinguish one artist from another. And, of course, music itself is an intellectual property asset, gaining copyright and allied rights once it is recorded in some material form.

To explore how intellectual property shapes, protects, and even inspires creative expression in music, we ran a panel discussion, led by Senior Partner Paul Cozens, where our panellists shared their fascinating experience and knowledge.

We heard from: Drew Ellis, Grammy-nominated graphic designer and photographer who created some of the most iconic album covers of all time; Dr Mark Gotham, whose work spans musical composition and computer science; Prof Simon Godsill, who is professor of Statistical Signal Processing in the Engineering Department at Cambridge University; and James St. Ville KC, who is a barrister with a significant music background.

We also invited two of our own attorneys to the panel, Emma Pallister, Chartered trademark attorney, and Dani Kramer, UK & European patent attorney and UK design attorney.

AI: for good or for evil?

Although music has been a universal language since before the 1st century AD (the earliest fragment of musical notation was found on a 4,000-year-old Sumerian clay tablet), the industry is always undergoing change. The last 100 years has seen the most significant transformation with the conception of pop music and the use of electronics. Now the rise of AI begs the difficult questions: what determines music individuality? What makes music, or anything, human? And can intellectual property law balance protection and creative freedom?

At Mathys & Squire, we have many attorneys who specialise in AI and the complex range of implications for managing intellectual property which arise as a result. These span from the extent to which inventors can protect their AI-related inventions to how creations can be protected from unsolicited use by AI or for AI training. Our panellists discussed the broad implications of AI for the music industry and how they can be approached by intellectual property law.

“Good artists copy, great artists steal”

Although this was once said by Picasso, he may have thought differently had he known about AI. AI has transformed the traditional methods of obtaining information. Machine learning models mine information by web scraping huge quantities of data, which trains them to satisfy almost any request. But such capabilities present elaborate legal challenges, as information from human creators is often used without permission.

For example, AI can produce a piece of music almost instantaneously, drawing on sources of existing music to meet user prompts. Last year in the US, Universal Music Group, Sony Music and Warner Records sued an AI model called Suno which creates music described as “original” by the platform. These record companies claimed that the model re-created elements from recordings which they owned, infringing their copyright.

Infringement or inspiration?

A musical composition is an intricate tapestry of external influences. As Dr Mark Gotham illustrated during the panel discussion with his piano rendition of Pachelbel’s Canon (from the 1600s) and Oasis’ ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’ (which builds on the same chord progression like many other recent pop songs), music composition often uses well-known phrases. Therefore, evaluating whether one composition infringes the copyright in another is complicated by the fact that they may both contain references to even earlier works.

But does the popular proverb “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery” still stand when it comes to AI-generated music? According to Damon Albarn, Annie Lennox, Kate Bush and a host of other artists, it does not. These musicians, among others, released an album on 25th February titled “Is this what we want” in protest at a proposed change in UK copyright law relating to AI. A similar sentiment was seen in the House of Lords, when the Peers voted for amendments to the UK Government’s Data (Use and Access) Bill, which were suggested by film director and peer, Baroness Beeban Tania Kidron. The amendments were proposed with the aim of protecting the intellectual property of creatives, ensuring that they are made aware how and when their work is used.

If AI-generated music is indeed an original work, another question follows: who owns it? But this is also a contentious topic, as the list of possible authors is long: the designer of the AI model, the individuals in charge of training the model, the individuals whose work is used to train the model or the individual who inputs prompts into the machine. Furthermore, musical creations consist of many different elements, including the lyrics, the melody and the beat. Licensing arrangements for music are already multi-faceted and, when AI is thrown into the mix, it becomes even more complicated. Copyright law cannot accommodate something which has no clear owner.

The patentability of AI

In addition, AI raises questions about the criteria for patent filing. For an invention to be patentable in the UK, it must: be novel, display an inventive step (i.e. not be obvious to a person skilled in the field), have an industrial application, and solve a technical problem. Pure mathematical method (and hence, sometimes “pure AI”) inventions are not patentable because they lack technical character, and merely specifying the technical nature of the parameters may not be sufficient on its own to remedy this. For an AI invention to be patentable it must have either a technical application or a technical implementation.

In practice, this means that unless the invention is a specific technical implementation of a machine learning algorithm that is particularly adapted to consider the internal functioning of a computer system or network it may be very hard to patent in this space. An argument that the provision of better music is a technical application would be unlikely to be met with success.

A new creative force

Paul Cozens ended the insightful panel discussion with a deciding question. Ultimately, all the panellists agreed that AI can be harnessed as a creative force rather than destroying creativity as whole. However, this is only possible if IP systems develop fast enough to accommodate all the issues which come with it.

In December of last year, the government published a consultation on copyright and artificial intelligence. The consultation presented a framework which would prioritise transparency, requiring AI developers to disclose the material used for training, and allow creators to reserve the rights of their work, opting out from use for data mining.

Just last week, a collective license was put forward by The Copyright Licensing Agency which would enable authors to receive remuneration when their content is used to train AI. The CLA portrayed this as a more viable alternative to the government’s current proposals.

We can stay hopeful that the government is able to develop a legal system which rewards rights holders and gives them control over their work, whilst also supporting the development of AI models by allowing access to high-quality data.

115 years of protecting creativity

World IP Day was also the perfect opportunity to celebrate our firm having been at the forefront of intellectual property law for 115 years. The event showcased our dedication as a firm to align our deep expertise with the cutting-edge of technology, as well as foster a culture of creativity and innovation.

Albert William Mathys founded Mathys & Co. in 1910 with a vision to protect the influx of revolutionary inventions in science, engineering and manufacturing at the start of the second Industrial Revolution. Our firm began in a small office in Chancery Lane, and has flourished into a global IP powerhouse, with hubs across Europe, China and Japan, adapting to every complex change in the legal landscape as we grew.

From protecting internal combustion engines in the early twentieth century to working with AI and life-changing biotech in the present day, we are proud to have 115 years behind us of combining technical knowledge with entrepreneurial spirit and a commitment to immaculate client service, and many more to come.

Below is a recording of the panel discussion for a deeper insight into the fascinating intersection between music and intellectual property.

Since the EU (Community) design system was first introduced in 2002, new technology – in particular new digital innovation – has given prominence to new types of “products” which the EU considers should benefit from design protection.

As part of ongoing efforts to modernise the EU design system, several key changes are being introduced. These changes aim to broaden and clarify the scope of design protection in the EU, while also making the system more accessible and user-friendly.

Non-physical “products”

In particular, as of 1 May 2025, the legal definition of the “products” that are eligible for design protection will now not only encompass products that are physical objects, but also products which materialise in a non-physical form such as graphic works or symbols, logos, and graphical user interfaces. The new regulations also explicitly recognise that animations, such as movements or transitions, of the features of a product can contribute to the appearance of designs and will therefore be explicitly eligible for design protection.

The “Locarno Classification”

Another change will be a simplification of how products are grouped together in design filings. Currently, to file products together as a multi-part design, products must fall within the same “Locarno classification.” For example, designs to a mobile device and a household appliance could not be grouped together in a multi-part application. This classification requirement is being removed, meaning that disparate products or features of the same overall system (with different Locarno classifications) can be filed together in a multi-part design filing. This new approach will reduce the complexity of design filings and will also reduce the up-front cost to applicants by consolidating what would previously have been several design applications into a single design filing.

Design rights holders will also be able to mark their products as having EU design protection by using a circled “D” symbol, similar to the symbols “®” and “©” that already exist for trade marks and copyright.

These changes are welcome, broadening the types of products that the EU design law protects to align with advancements in technology and technology commercialisation which have taken place over the last 20 years.

If you have any questions about obtaining design protection for your products, please contact our designs team.

We are delighted to announce that we have received the Committed Badge from EcoVadis, recognising our ongoing efforts toward sustainability and responsible business practices.

EcoVadis is a globally recognised sustainability assessment platform that evaluates companies on their environmental, social, and ethical performance.

The EcoVadis assessment includes 21 sustainability criteria with a comprehensive review of policies, actions, and results across four main categories: Environment, Labor & Human Rights, Ethics, and Sustainable Procurement.

As part of our commitment to society, our people and the environment, at the start of this year we completed a thorough assessment of our business sustainability practices through EcoVadis, and are now proud to share our results.

Why is it important to us?

Receiving the EcoVadis Committed Medal is a positive step in our ongoing sustainability journey. It reflects the foundational work we’ve done to integrate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles into our operations. This recognition provides an external validation of our commitment to responsible business practices, and it encourages us to continue building on this progress.

Click here to read more about our Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives.

In the past couple of decades, the number of filed European patents related to defence has risen dramatically. 10,582 individual patent family applications were published between 2000 and 2004, whilst 28,307 were published in the last four years. The areas of “wireless communications” and “aircraft and helicopters” showed the largest jump, largely due to recent developments in drones and cyber security technologies.

UK Government’s Investment in Innovation

To encourage the development of these types of novel technologies in the UK, the Spring Statement, led by Rachel Reeves, included a substantial commitment towards innovation for military purposes. Specifically, Reeves has announced that the government will set aside £400 million for innovative technology and has promised to prioritise UK tech firms, in particular start-ups and SMEs.

This funding arrives on the back of other initiatives already established in the UK government’s effort to drive innovation. In December, the Defence Secretary, John Healey, revealed plans to develop a new Defence Industrial Strategy, to be published in late Spring of this year. The strategy will outline the government’s efforts to prioritise defence as one of the eight “growth-driving” sectors. This includes a commitment to supporting UK businesses, creating new venture opportunities through partnerships with the Ministry of Defence, increasing jobs in the defence sector across the UK, and focusing on novel and early-stage technology. A scheme created specifically to link the Ministry of Defence with such technology is the Defence and Security Accelerator, which seeks out and funds innovation to aid UK defence and security.

But as the government calls for a defence ecosystem characterised by growth and innovation – and provides substantial funding to drive this growth – important considerations arise in how defence manufacturers can best manage their intellectual property.

Balancing Protection and Privacy

One obvious consideration is how to handle potentially sensitive, or secret, subject matter and how to protect inventions that might have national security implications. A common fear when pursuing patent applications for military technologies is the risk of Section 22 directions. This is where the UK Patent Office prevents the publication or dissemination of applications containing sensitive subject matter. Another consideration is how best to commercialise technology whose primary use will be by governments during times of conflict.

In practice, these sorts of Section 22 directions are often avoidable. The UK Patent Office’s 2023 filing data indicates that only 35 directions under Section 22 were issued in that year despite a large number of filings by defence companies (BAE Systems alone filed 116 new applications in 2023).

A large reason for this is that technologies originally intended for military applications often turn out to have substantial other, e.g. civilian, use cases. With careful consideration it is often possible to protect an underlying invention that can be applied to these other use cases without publishing any sensitive information. One example of such a technology is the GPS system, which started life as a purely military technology before being opened up to civilian use. By focusing on these alternative uses, it is often possible to obtain meaningful, and commercially valuable, protection, without risking a Section 22 direction.

Building A Strategy for Defence Tech Firms

To summarise, due to the increased funding being made available, the next few years offer the opportunity for substantial innovation in the defence sector. Companies involved in this innovation should be careful to protect their intellectual property while bearing in mind the unique complexities in this area.

Many of the potential pitfalls can be overcome with careful strategizing. If managed properly, the military technologies of this decade could well turn into ubiquitous civilian technologies in the next decade or even sooner. Companies with a strategy that effectively protects their intellectual property in the short term will be well placed to reap the benefits in the long term.

Mathys & Squire partners with the Swiss Startup Association as a Legal Partner to support the IP work of startups and small businesses within their network. Partner Andrea McShane, Managing Associate Aymeric Vienne and Associate Danielle Champagne form our contact team.

The Swiss Startup Association (SSA) is a company dedicated to supporting small businesses with a plethora of networks and resources. With over 1600 startup members, they help encourage the sustainability of the latest innovation and creativity in Switzerland.

Regarding the new partnership, Partner Andrea McShane writes: ‘As an ETH graduate the Swiss start up landscape is close to my heart – and it is such a pleasure to be involved, and to be able to give back in this way. Hopp Schwiiz!’

Through the Swiss Startup Association, Mathys & Squire are offering three different start up packages tailored for the different needs of businesses. As well as this, for SSA members, we are offering a free initial patent filing strategy consultation.

Andrea will also be attending the 2025 Founders Day in Zurich on the 15th of April. Taking place at the Google Campus Europaallee, the event is an opportunity for startups to hear from founders and investors who will share their own experiences, knowledge and expertise to the attending audience.

Click the link here to read more about the partnership.

We are excited to share that our team in Oxford have moved to a new office at Blue Boar Court in the centre of the city. Along with six other science and tech companies, Mathys & Squire have relocated to The Oxford Trust’s new Oxford Centre for Innovation. The official address of our office is now Blue Boar Court, 9 Alfred Street, OX1 4EH.

Opening the office in 2019, Mathys & Squire’s presence in Oxford, an industry hotbed for startups, founders and global brands, reflects our commitment to supporting innovation. The office’s location in the new Centre for Innovation, which sits on the doorstep of University of Oxford’s key academic and research institutions, strengthens our relationship with existing and potential clients.

Mathys & Squire is delighted to have been recognised in JUVE Patent’s UK rankings 2025 for the sixth consecutive year in the fields of ‘Pharma and biotechnology’, ‘Medical technology’, ‘Chemistry’, ‘Digital communication and computer technology’ and ‘Electronics’.

As well as a practice-wide recommendation for the firm, four of our Partners have been recognised as Recommended Individuals: Philippa Griffin, Hazel Ford and James Wilding for ‘Pharma and Biotechnology‘, and Chris Hamer for ‘Chemistry‘.

The JUVE Patent rankings are a result of thorough research conducted by an independent team of journalists, who send out questionnaires and conduct interviews with lawyers, clients, legal academics and judges. In the 2025 edition, UK patent practices, solicitors and barristers who, according to the in-depth research, have a leading reputation in the UK patent law market are celebrated.

To see the JUVE Patent UK 2025 rankings in full, please click here.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into the digital landscape is enabling a fundamental shift in how organisations approach innovation and the commercialisation of intellectual property (IP). As AI technologies continue to advance at an exponential rate, understanding their impact on IP management and monetisation has become essential for maintaining a competitive advantage in the digital sector.

The Power of AI in Digital Innovation

AI technologies are a catalyst for digital transformation, revolutionising how companies process data, automate workflows and accelerate innovation. The applications of AI span from predictive analytics and machine learning algorithms to autonomous systems and intelligent automation platforms. These capabilities enable organisations to process vast quantities of data with unprecedented speed and accuracy, leading to more informed decision-making and accelerated innovation cycles. We also see regular advancements in AI coding abilities across all the major AI platforms, as well as in focused AI coding tools.

Economic analysis highlights AI’s dual role as both a facilitator and disruptor of innovation, challenging traditional IP frameworks to balance incentivisation with societal interests.

Just as the European Patent Office is integrating AI into its everyday tools as it examines patent applications, we recommend that IP owners also integrate AI into their everyday operations. For example, in biomedicine, AI-driven tools are now a key part of drug discovery. Within the university IP commercialisation function, teams, such as at Texas Tech, are finding value in using AI for tasks such as processing invention disclosures, prior art searches, market assessment and contract management.

Furthermore, emerging trends include AI-driven dynamic licensing models, AI agents used for IP commercialisation, finding potential infringers, and blockchain-powered IP transaction systems. We also observe an increase in the pace of advancements in the underlying AI technologies which support many AI-powered deployments within innovating companies.

Strategic IP Management and Optimising IP Commercialisation in the AI Age

At Mathys & Squire Consulting, we recommend organisations carefully consider how to protect and commercialise their innovations, particularly in areas such as proprietary algorithms, data processing methodologies, and novel digital solutions. AI-based technologies have created new opportunities in intellectual property management, and AI related filings continue to increase. However, new challenges have also arisen, as key issues such as ownership and patent eligibility remain contentious for AI-generated innovations.

Beyond filing, companies should consider data ownership, internal processes to avoid risk, staff training on IP and intangible assets, and most of all the company’s intellectual property commercialisation strategy. Success in this domain requires a sophisticated understanding of both technological advancement and how increased revenue can be delivered, whether through direct commercialisation, licensing or sale of unused or unwanted intangible assets.

Why Expert Guidance Matters

For organisations aiming to navigate this complex landscape, expert guidance is crucial. Mathys & Squire Consulting offers the expertise needed to unlock the full commercial potential of the intangible assets and intellectual property which arise from AI-based digital innovations. With a deep understanding of AI technologies, their implications and their commercial potential, our team collaborates with innovators and innovative organisations to recognise and manage your intangible assets, and to optimise your commercial success. Our strategic approach ensures that your organisation can capture and convert its innovative ideas into profitable outcomes.

AI and IP: Next Steps?

Reach out to Mathys & Squire Consulting today to discuss your intangible assets, your intellectual property, how you are using or plan to use AI, and your IP commercialisation strategy.

We look forward to collaborating with you to unlock the value in your AI based innovations.

On 12th March, Mathys & Squire sponsored the 2025 NLIL conference for the second year running, hosted at LSE. Partners James Pitchford and Anna Gregson , Technical Assistant Louis Brosnan and Trainee Trade Mark Attorney Tanya Rahman all spoke at the event.

The Non-Law Into Law (NLIL) Conference was first held in 2024 and returned last week after their debut success last year. The event was tailored to students from a diverse range of academic disciplines studying a total of 117 different degree subjects, and successfully highlighted the various pathways available for those interested in pursuing a legal career, even though they may not be currently studying law.

Hosted at LSE, societies from various universities including Imperial College, Warwick, UCL, Durham and Queen Mary were in attendance, with over 300 tickets sold to students who actively listened and engaged with a series of panel discussions, presentations and interactive workshops.

Photo from the 2025 NLIL Conference

From our Mathys & Squire team, we led an IP Workshop, which presented an introduction to Intellectual Property to the attending students, covering the various areas of patents, trade marks, registered designs and copyright, as well as a Careers in IP seminar, examining the different professional paths within the field.

It was a pleasure to attend the event and our team was extremely impressed with the engagement and enthusiasm demonstrated by the attending students.

Find more about the NLIL conference on their website here.