In this series, our IP experts will reflect on some of Google’s top trending topics throughout the unprecedented year of 2020. In our final article of the series, partner Juliet Redhouse and technical assistant Jonathan Israel explore arguably the most significant of all topics to come out of 2020 – the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing vaccinations.

2020 marked a year of global upheaval following the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the year ended with more positive news following the regulatory approval of a number of vaccines for the start of the largest global vaccination campaign in history.

The world’s most innovative life sciences companies and institutions have risen to the challenge of generating safe and efficacious vaccines for global distribution at rapid speed. The pace at which these vaccines were developed largely arose from the repurposing of existing vaccine technologies to target the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus variant. However, clearly challenges have been overcome in both the design of the vaccine and its large-scale production, which will have resulted in new patent applications in 2020.

With 64 vaccine candidates in clinical development and a further 173 in pre-clinical development (source: WHO), 2021 should see the approval of further vaccine candidates. We are also likely to see continued focus on the emergence of new coronavirus variants. Some innovators have already started to shift their focus towards the development of vaccines tailored to new variants, and these efforts are likely to be accompanied by new patent filings.

We may also see patent filings around the optimisation of vaccine dosage regimens. The majority of the COVID-19 clinical vaccine candidates employ a two-dose regime, in the form of prime and booster doses, which has itself raised controversy over the benefits and trade-offs over lengthening the interval period. Moving into 2021, as the risk from new variants is brought into sharper focus, we may see some innovators adjusting the dosage regimen to compensate. For instance, a third booster dose has already been mooted as a possible future requirement and clinical trials are already planned, while the benefits of adjusting the prime dose have also been explored.

2020 has also seen an urgent need for COVID-19 treatments, which have until now been met by the repurposing of existing medicines. The UK Recovery trial was the first in the world to provide clinical trial evidence of a safe and effective COVID-19 treatment in the form of dexamethasone, a steroid that has been in existence for decades and has a well understood mechanism of action. In 2021, UK approval for antibody treatments tocilizumab and sarilumab has followed. Encouraged by these findings, and with improved understanding of the mechanisms of COVID pathogenesis, innovators are likely to intensify research efforts towards repurposing existing therapies to strengthen the therapeutic armoury. We are therefore likely to see new patent filings centred on further medical uses of existing therapies.

As 2021 moves into brighter times, it is likely that new tools will be required to adapt to a world living with COVID-19. We would particularly expect COVID-19 diagnostics to continue to play an important role, predominantly to monitor local COVID flare-ups and for targeted surveillance of new mutations. As domestic and international travel begins to restart, demand for reliable and rapid diagnostic tests will intensify and further investment and development in this area is likely. Further innovations in the form of protective measures for offices and public transport are also likely to be enhanced for if – and when – the workforce returns to the office.

Previous articles in our 2020 trending topics series include: ‘Tiger King – Murder, mayhem, mullets… and trade mark law‘ and ‘Face masks and design protection‘.

In this series, our IP experts will reflect on some of Google’s top trending topics throughout the unprecedented year of 2020. In our second article, associate Max Thoma considers the small (but mighty) face mask, and how its design might be protected under registered design law.

2020 was notable for many reasons, including the sudden appearance in the Western world of a new consumer article that almost everyone felt a need to acquire – the ubiquitous face mask. From the humble blue disposable medical mask, to the lovingly homemade colourful mask, to the high-end designer models, face masks were everywhere in 2020 and are likely to stay ever-present in our pockets, in our bags and (of course) on our faces, until deep into 2021 at least.

Predictably, the emergence of this new category of products saw designers seeking to impart their own spin on the face mask and file registered designs to protect their new creations. The UK design register shows numerous designs for face masks, together with packaging for such face masks. There are also several registered designs for protective wallets and bags for face masks, along with more exotic items such as combined t-shirts and masks – might such products be a growth area in 2021? Whatever the product, designers should make sure that appropriate registered design protection is sought based on carefully prepared drawings which clearly identify the key features for protection (and, ideally, which ‘disclaim’ features of lower importance).

2020 was also notable in registered design terms for being the final year during which EU registered designs covered the UK. The Brexit transition period expired at the end of December 2020, so it is now necessary for applicants to seek design protection in both the EU and UK separately. Existing EU registered designs were automatically ‘cloned’ in corresponding UK designs upon the expiry of the transition period, so designers with already registered designs should not have lost any rights. Although the need to file registered design applications in both the EU and UK is burdensome, the UK design system is fortunately substantively similar to the EU system and involves very low official fees, meaning that new combined UK and EU design applications involve only a small increase in cost and complexity as compared to filing only a EU registered design application (as most applicants did prior to Brexit).

Whether your new design relates to a face mask or something else entirely, you register it in both the UK and EU separately to ensure its protection. Visit our Brexit page for more information.

Other articles in this 2020 trending topics series include: ‘Tiger King – Murder, mayhem, mullets… and trade mark law‘ and ‘COVID-19 vaccinations‘.

In this series, our IP experts will reflect on some of Google’s top trending topics throughout the unprecedented year of 2020. Our first article, written by trade mark associate Robin Richardson, explores the significance of brand protection, using hit Netflix series Tiger King as a case study.

The 2020 lockdowns were a difficult time for many. Some turned inwards, some turned to exercise, but most turned to Netflix. Of all the popular series and films released throughout 2020 by the world’s largest subscription streaming service, one docu-series truly took the crown from The Crown, and why not – it is after all Tiger King!

For those who have not had the opportunity to ‘Baskin’ all the glory that is the tale of Tiger King, the documentary centres around the rivalry between two individuals, Joe Exotic and Carole Baskin. Joe Exotic (who sports a blonde mullet which would make most 80’s rock stars green with envy) ran a questionably legal big cat zoo in Wynnewood, Oklahoma which drew the wrath of Carole Baskin, a self-proclaimed animal rights crusader who founded an equally questionable big cat ‘rescue’ centre.

The rivalry between the two, which should have centred around the care of big cats, ultimately turned to a personal feud so bitter that it lands Exotic in jail with, amongst other severe animals rights violations, a conviction for attempting to hire a hitman to kill Baskin.

But what exactly does the documentary have to do with intellectual property (IP) law? Well, Baskin’s goal was purportedly to shut down Exotic’s zoo permanently. Whilst Exotic’s own actions may have landed him in jail, it was Baskin’s successful trade mark and copyright disputes which handed her control of Exotic’s zoo in June 2020.

At the centre of the disputes was Exotic who, in his quest to taunt his rival and damage Baskin’s corporation, decided to use her corporation’s trade mark ‘BIG CAT RESCUE’ in relation to a road show exhibiting big cats across the US. Exotic, however, did not use an identical trade mark, instead adding the word ‘ENTERTAINMENT’ to form ‘BIG CAT RESCUE ENTERTAINMENT’, which (unfortunately for him) was not sufficient to avoid an infringement of the registered trade mark. His case was not helped by the multitude of copyright infringements that were levelled against him for the unauthorised use of photographs owned by Baskin and her corporation. In the end, the court ordered that Exotic pay $953,000 in damages (primarily relating to the trade mark dispute) and legal fees. With Exotic unable to pay the order, the court ordered control of the zoo to be handed over to Baskin in June 2020.

Exotic’s actions and Baskin’s success highlights both the strength of trade mark and copyright protection, as well as the dangers of not having a grasp of IP law and the implications of infringement when launching a business or sharing content online. Although the case of Tiger King is unusual, to say the least, it does serve as a reminder that proper counsel should always be sought before using a trade mark or sharing content that you do not own – after all that’s what all the “Cool Cats And Kittens” would do (to quote Carole Baskin)!

Other articles in this 2020 trending topics series include: ‘Face masks and design protection‘ and ‘COVID-19 vaccinations‘.

In recent news, Japanese car maker Nissan has confirmed that it will localise manufacture of its 62kWh battery at its plant in Sunderland. This comes as a welcome boost to UK businesses involved in the automotive supply chain in the North East, many of which the Mathys & Squire team helps to represent.

With the UK government’s commitment that all cars made by 2030 must at least be partly electric, it is clear that electric vehicles are very much part of the future. Nissan’s announcement follows hot on the heels of Britishvolt’s recent news that it would be creating the UK’s first “gigaplant”, creating up to 3,000 jobs, on the site of the former Blyth Power Station in Northumberland. Britishvolt’s £2.6bn investment is a sign of yet further confidence in the expertise and highly skilled workforce in the region.

Having been partners of the North East Automotive Alliance for several years now, and working with some highly innovative businesses in the region, such as Hyperdrive Innovation and BorgWarner, we understand first-hand the skills, expertise and innovation that are coming out of the region and are excited to be working with businesses in the North East to help protect their intellectual property in what is proving to be an international scramble for the investment of future automotive technology.

In this feature by Lawyer Monthly, partners Andrew White and Chris Hamer provide their thoughts on the patent trends to look out for in 2021.

Artificial intelligence – Andrew White

As with recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) looks set to continue to be a trend for 2021. With the publication in Nature in November 2020 announcing that DeepMind’s AI “AlphaFold” will “change everything”, we are likely going to see further developments where AI is used to solve problems relevant to humanity – particular in spaces where AI is used to solve problems in the chemical and life sciences fields, and relevant IP in this area is likely going to more and more relevant as commercial applications come to fruition. Partly in recognition of this, the European Patent Office (EPO) held a Digital Conference in December 2020 on “the role of patents in an AI-driven world”, with the EPO calling AI “one of the disruptive technologies of our time” and recognising that patenting activity in this area has increased dramatically recently.

Patent trends – Chris Hamer

Plant based foods – The growth in this sector is undeniable with the market expected to reach $74.2bn by 2027. With political and social pressure to improve diets, and initiatives such as Veganuary,food manufacturers will invest millions to be able to provide innovative plant based alternatives which truly fool the consumer into thinking they are eating the real thing. Throw into the mix the fact that different countries only have access to certain raw materials and you can see just how difficult the challenge is…

Coronavirus – Much has been written about the vaccines and equipment developed over the last year, and whilst there will continue to be improvements, we expect to see an increase in digital technologies (e.g. virtual reality, network security, digital marketing apps, social media, e-commerce and videoconferencing, etc), which, in the long run, will hopefully drive productivity gains in a new business and social revolution.

Brexit – Now that the UK has officially left the EU, it will be interesting to see if UK and EU law really will diverge as some have feared, or whether the previous decades of harmonisation will generally remain for the foreseeable future.

These comments were first published in the January 2021 edition of Lawyer Monthly Magazine.

At the end of 2020 the German parliament passed (for the second time) the legislation necessary for Germany to ratify the Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA). This followed a ruling earlier in 2020 from the Federal Constitutional Court which nullified the first attempt to implement this legislation due to failure to meet a parliamentary majority of two-thirds as required under the German constitution.

Following the second attempt at enacting the relevant law, it has now been reported that two new complaints relating to the UPCA have been filed with the Federal Constitutional Court. Once again, the court has asked the German President not to bring the legislation into force while these complaints are reviewed. Few details are available regarding the new complaints so far, although it is understood that one of them has been filed by the same party who was behind the previous, successful complaint. It is also understood that a preliminary injunction has been sought by one of the complainants to formally prevent the German government from ratifying the UPCA pending the Constitutional Court’s final decision.

If it comes into force, the UPCA will create a common court system for patent litigation in the participating countries, along with a single patent covering those countries. The project has been beset by repeated delays over the years, and the UPCA cannot enter into force without German ratification. The new constitutional complaints are therefore likely to create further delays. A timescale is not yet foreseeable with any certainty, although the previous constitutional complaint took approximately three years to resolve.

More details will be reported if and when these become available.

Mathys & Squire partners Anna Gregson, Dani Kramer and Martin MacLean have been featured in the inaugural IAM Strategy 300 Global Leaders guide.

The guide shines a light on specialists from the major IP markets across North America, Europe and Asia, with a wide range of expertise in IP-intensive sectors such as high-tech and life sciences. Consisting of interviews with these leading strategists, the guide provides insight into how their careers have developed, their thoughts on key trends in the market and their top tips for other IP practitioners looking to progress.

The full Global Leaders interviews are available here: the ‘commercially savvy’ and ‘ultimate safe pair of hands’ Anna Gregson; ‘highly intelligent, vastly knowledgeable and committed to excellence’ Dani Kramer; and ‘one of the top guns of the UK life sciences patent scene’ Martin MacLean.

There is a range of IP options available to manufacturers looking to protect their treasured recipes, whether through copyright, a trade secret or a patent, but how do you know if your tasty treat is eligible and, if so, which IP right you can secure? In this article, published in Baking Europe in December 2020, managing associate Laura Clews provides a brief overview of the options available, along with benefits and pitfalls of each for you to chew over…

The festive period is now upon us, so thoughts turn to spending time with our families, decorating the tree and, of course, food. At this time of year, food and drink manufacturers provide unique twists on classic treats and decadent desserts designed to tickle every taste bud. It is common to spend more on food and drink during the holidays and perhaps even treat ourselves to some luxury priced goods. Statistics by GoCompare Money predicted that, collectively, British households would spend £4.7 billion on food and drink products over the Christmas period in 2018. Accordingly, for manufacturers that manage to produce the ‘must have’ items of the year, Christmas can be a very profitable time. But how do you prevent other manufacturers copying your culinary creations and reducing your market share? Essentially, is it possible to protect a recipe?

Can I copyright a recipe?

Copyright is an exclusive legal right that arises automatically on the creation of an original work and can be used to prevent others from using or commercially exploiting this work without permission. Copyright protects, amongst other things, literary creations, artistic works, original non-literary written work and the layout of published editions of written works, but does this IP right extend to recipes?

Unfortunately, under UK law, copyright protection does not encompass a collection of ingredients or a list of instructions (such as the method steps contained in a recipe which are considered merely functional). Therefore, following a recipe to produce a particular food or drink product would not infringe any copyright of the original author.

Some copyright protection may be provided in the particular literary expression used to describe the method steps of your recipe, however, this protection would not prevent others from publishing your recipe as long as it has been expressed in a different way.

General concepts or ideas cannot be protected under copyright either, and so producers of next year’s cronut would not be able to prevent other companies constructing and/or publishing recipes to make the same or a similar treat (unless other forms of IP protection are in place).

Copyright protection afforded to an author is dependent on national law and so can vary depending on the country in which the original work is considered, however many countries around the world are Contracting Parties to the Berne Convention. The Berne Convention defines minimum standards of protection under copyright (i.e. the same protection must be given to works originating in other Contracting States as would be provided for works originating in that state) and the minimum duration of protection (generally 50 years after the death of the author with the exception of applied art, cinematographic and photographic works) under copyright law.

Is it best to keep recipes as a trade secret?

Trade secrets encompass any information that is commercially valuable to a company, including secret recipes. In accordance with The Trade Secrets (Enforcement, etc.) Regulations 2018, to ensure that your recipe is covered as a trade secret you simply need to demonstrate that:

(a) it is secret in the sense that it is not generally known among, or readily accessible to, people who normally deal with that kind of information

(b) it has commercial value because it is secret, and

(c) reasonable steps have been taken in order to keep the information secret.

The requirement of ‘reasonable steps’ can include password protecting documents containing essential information and marking them as ‘confidential’, ensuring trade secrets are protected in employment contracts, using confidentiality agreements – such as non-disclosure agreements – when discussing confidential information with anyone outside your company, limiting the number of people with access to the information, and training staff members on how confidential information should be handled.

While there is no uniform legal framework globally for a ‘trade secret’, in general, unfair practices with regards to confidential information, such as breach of contract or breach of confidence, are considered actionable. Similarly, the remedies available for unlawful acquisition and use of trade secrets can vary based on the legal system in place. For example, trade secrets in the US are governed by The Economic Espionage Act (EEA), under which the theft of a trade secret can result in imprisonment and fines.

What are the benefits of trade secrets?

The basic requirements to ensure that your recipe is classed as a trade secret are simple to implement, cost-efficient and provide effective protection in some cases. Furthermore, the protection provided by a trade secret will remain in force for as long as that information remains secret.

In addition, ownership of a trade secret can be used as an effective marketing strategy, creating hype and mystery around your product. Some of the best-known examples of trade secrets in the food and drink industry include recipes for Coca Cola and the KFC coating (containing a blend of 11 herbs and spices). Both companies publicise the extreme methods employed to ensure that these recipes do not fall into the wrong hands, emphasising just how special and unique their products are. For example, Coca Cola states that the only notation of its recipe is stored in a purpose built vault at the company headquarters in Atlanta and only two senior executives know the secret formula at any one time (these staff members are, of course, forbidden to travel on the same plane). Similarly, KFC has publicised that its secret recipe is secured in a vault in Louisville, which has been reinforced with two feet of concrete to ensure that competitors cannot tunnel or drill into the vault.

In the event that a third party unlawfully obtains or uses information classed as a trade secret, possible remedies available to the owner under UK law include: obtaining a court order (i.e. an injunction) to prevent the use or disclosure of the trade secret, recall or destruction of any infringing goods from the market and monetary relief in the form of damages.

What are the potential issues with trade secrets?

Trade secrets can be useful where it is difficult (if not impossible) to derive the ingredients or process used to produce the food or drink product. However, they do not provide protection if another company legitimately produces the same product or manufacturing process. They also do not provide protection if a third party is able simply to reverse-engineer the product.

Further challenges may arise as a result of the UK’s Food Labelling Regulations, which require food and drink products with two or more ingredients (including additives) to provide a list of the ingredients in order of weight (with a few exceptions). Accordingly, if your secret recipe relies on the inclusion of a specific ingredient, you may be required to publicly disclose this information.

For some companies, patents may provide a more reliable form of protection particularly where a consumable product could be reverse-engineered, if the essential ingredients must be disclosed because of UK Regulations, or if there are other competitors/potential competitors working towards the same target product.

What protection do patents provide for recipes?

A patent is an IP right granted by a specific country’s government for a limited time period, typically 20 years from the date of filing. Where a patent is directed to a product, it allows the owner to stop others from making, using, offering for sale, selling, or importing that product within the territory for which the patent has been granted. For a specific process, the owner can prevent others from using that process within the relevant territory without the patent owner’s consent.

What can be protected?

A variety of food and drink inventions are suitable for patent protection – for example where the product has an improved taste, texture or appearance whilst reducing fat or sugar content; a combination of ingredients which produce a synergistic effect; a non-obvious substitution for a commonly used ingredient (for example, E numbers); and methods of altering the flavour profile of products.

Faster or more cost-effective manufacturing methods; methods of producing new products or method steps which provide an unexpected result can also be suitable for patent protection.

In the same way that trade secrets can be used to publicise particular food and drink products, owning a patent can also increase public awareness and interest. In one example, as highlighted in numerous articles/blog posts, Nestlé developed a method of producing porous particles containing sugar which could be used to reduce the sugar content of confectionery without detrimentally affecting the sweet taste expected by consumers (see WO 2017/093309).

What criteria do I need to meet?

In order to obtain a granted patent, most territories require the inventor to at least demonstrate that the invention is novel, involves an inventive step and is capable of industrial application.

Novelty

The claimed invention must not be publicly disclosed before the date on which the application is filed -e.g. publicising your invention on the company website/blog/social media, selling the product, or displaying it a tradeshow (where someone might determine the novel features from the product itself) could invalidate any later filed patent application.

For this reason, it is essential that manufacturers avoid discussing the invention with anyone outside their company (e.g. investors or suppliers) before the date on which the patent is filed, or, if this cannot be avoided, ensure that confidentially agreements are in place beforehand.

Inventive step

The claimed invention must also provide a non-obvious solution to a technical problem in view of what was known before the filing date of the patent application. Essentially, the invention must be shown to go beyond standard development within that field. The assessment of inventive step can vary depending on the particular jurisdiction in question and so it is often beneficial to seek professional advice from a local attorney when determining whether your invention would likely be considered to meet this requirement.

Industrial application

It is necessary also to show that the claimed invention is capable of exploitation within an industry. Most products and processes within the food and drink industry inherently meet this requirement.

What are the potential issues?

Patenting inventions can be a costly process, especially as the number of territories in which you require protection increases, so it is beneficial, particularly for start-up companies, to carry out a critical assessment of where their product or process will be sold. Alternatively, if their company does not intend to exploit the invention, it is important to determine where they are most likely to license the product/process.

As patent protection typically only lasts for 20 years from the date on which the application is filed, it is worth noting that upon expiration, the recipe, product or process can be freely used by other companies.

Whilst there are different options available for protecting the delectable creations developed by food and drink manufacturers, the type of protection best suited to these products can depend on the product itself and, of course, the commercial strategy of the business.

Mathys & Squire is delighted to have been recognised in JUVE Patent’s UK rankings 2021. Now in its second year, the guide brings together UK patent practices, solicitors and barristers with leading reputations in the UK patent law market.

Despite the challenging events that took place in 2020 (the global coronavirus pandemic, Brexit and the UK’s withdrawal from the UPC agreement to name just a few), JUVE Patent’s research has shown that ‘the UK’s patent lawyers have held on tight’ and that the ‘market remains more or less stable’, in the face of adversity.

For the second year, Mathys & Squire has been featured as a recommended firm in the category of Patent Filing – specifically in the fields of pharma and biotechnology; medical technology; chemistry; digital communication and computer technology; electronics; and mechanics, process and mechanical engineering.

Partner Chris Hamer has received a specialist Leading Individual ranking in this year’s guide, one of only 10 UK patent attorneys noted for their technical speciality – see here.

Chris Hamer and Jane Clark have retained their Recommended Individual status for a second year for their expertise in ‘Chemistry’ and ‘Digital communication & computer technology/mechanics, process and mechanical engineering’ respectively, while Hazel Ford and Philippa Griffin have been newly awarded rankings in the 2021 guide as Recommended Individuals in the fields of ‘Pharma and biotechnology’.

To see the JUVE Patent UK rankings for 2021 in full, please click here.

Just two months after the UK Supreme Court’s decision (as reported here) which held that a UK court has the jurisdiction to set global SEP rates, the Shenzhen Intermediate Court made the first decision ever (Guangdong Oppo Mobile Telecommunications Corporation, Ltd v Sharp Corporation) to confirm a Chinese court’s jurisdiction to determine global FRAND rates for SEPs.

Background

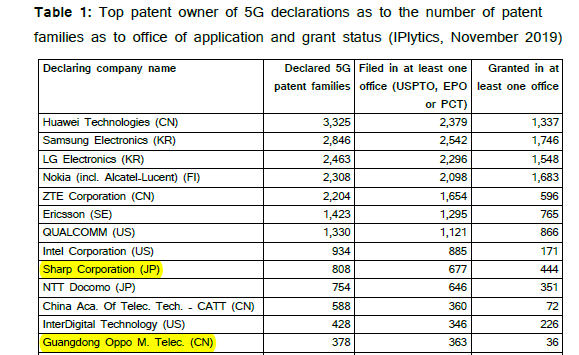

Guangdong Oppo Mobile Telecommunications Corp., Ltd (Oppo) is a Chinese company specialising in electronic and mobile communication products such as smartphones, audio devices and power banks. Sharp Corporation (Sharp) is a Japanese corporation that designs and manufactures electronic products. In the latest 5G patent report released by IPLytics, both Sharp and OPPO ranked as top patent owners of 5G patents (as one indicator of leadership in the telecoms industry) and Oppo was described as a company ‘newly entered into the market’.

Back in October 2018, Sharp sent Oppo a list that included a large number of SEP patents that Sharp was willing to license to Oppo. Oppo and Sharp then started licensing negotiations in February 2019. During the negotiations, Sharp filed patent infringement lawsuits against Oppo in both Japan and Germany for infringing its 4G/LTE patents.

The case

In March 2020, Oppo filed the first instance case against Sharp at the Shenzhen Intermediate Court for:

- Sharp’s breach of FRAND terms during the licensing negotiation, including ‘coercing Oppo into negotiation using infringement injunctions, overpricing and unreasonably delaying the negotiation’;

- global SEP rates of Sharp’s 3G, 4G and Wi-Fi SEP portfolio; and

- a compensation of 3 million RMB (350,000 GBP) for the breach of FRAND terms from Sharp.

The decision

Sharp raised an objection to the Shenzhen Intermediate Court’s jurisdiction over this SEP licensing dispute, arguing that the case should be dealt by a Japan Court, and that the global SEP rates for Sharp’s 3G, 4G and Wi-Fi SEP portfolio is beyond the jurisdiction of the Shenzhen Intermediate Court. The Shenzhen Intermediate Court made a decision in respect of Sharp’s jurisdiction objection in October 2020, as follows:

Whether a Chinese court has jurisdiction over the case

In light of the fact that an SEP licensing dispute is neither a typical contract dispute nor a typical infringement dispute, the Shenzhen Intermediate Court considered a few factors to determine the jurisdiction, such as whether the implementation of the patent or the performance of the contract, is within the territory of China – i.e. whether the SEP licensing dispute is properly connected with China. If one of such actions is within the territory of China, the case shall be deemed to have a proper connection with China and the Chinese court shall have jurisdiction over the case.

In the present case, the plaintiff Oppo is a Chinese company and its production, research and development take place in China. The defendant Sharp is the patentee of the Chinese patents and has property interests in China. Therefore, the court held that the case is properly connected with China and the Chinese court thus has jurisdiction over the case.

Whether the Chinese SEP rates should be separated from the global SEP rates

The court first pointed out that evidently, the previous licensing negotiation between the two parties concerned the global SEP rates of Sharp’s 3G, 4G and Wi-Fi SEP portfolio.

Secondly, the court held that global SEP rates will improve the overall efficiency by solving the dispute between the two parties fundamentally and avoiding multiple litigations in different countries – and therefore such global SEP rates are in line with the intent of FRAND terms and should not be separated from the Chinese SEP rates.

Conclusion

This might be one of the first cases worldwide that involves setting global rates for Wi-Fi SEPs. The consideration of global SEP rates has thus expanded from cellular networks such as 3G and 4G to WLAN.

Perhaps more importantly, this decision holds that a Chinese court is competent to hear issues relating to the setting of global FRAND rates for SEP patents, much like the UK Supreme Court recently held that it was competent to decide on the setting of global FRAND rates for SEP patents. However, this first instance decision was ruled by an intermediate court in China. Therefore, the decision may be appealed, and it will be interesting to see whether this decision will be upheld by the Chinese Supreme People’s Court.