As the use of generative AI becomes ubiquitous, is the patent system ready for an influx of AI generated inventions? And how might it handle AI inventions which are beyond our understanding?

It seems AI is everywhere. If not now, then soon. The patent world is no different. Patent offices are already using AI to improve the subject classification of applications and searches for prior art documents. Patent attorneys are looking to AI to assist with drafting specifications and responses to examiners. As for inventors, the thought of using AI both to assist with the inventive process and to reduce the cost of preparing a patent specification is a tempting prospect.

Earlier generations of AI used deep-learning to discover patterns in existing data and led to some notable (and in the case of DeepMind’s protein structure predictor Alphafold, Nobel-prize-winning) inventions. More recently, generative AI, powered by large-language models (LLMs) and embodied in chatbots such as ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude and others, has taken matters in a more creative direction.

When prompted, LLMs are characterised by fluent, persuasive output, capable of passing the Turing test, confounding users as to whether they are actually interacting with a human. But they can also be notoriously sycophantic and prone to hallucination. In short, there is a fundamental problem: AIs make things up. Convincingly. For an inventor using AI, will it be clear when invention has crossed the line into fantasy?

Almost every patent attorney will at some time in their career receive a call or an email from an inventor who believes they have made a groundbreaking invention. The world’s energy crisis is solved. Interstellar space travel is possible. Machines, once set in motion, operate forever, generating limitless energy with every turn. Often these ‘inventions’ are easily shown to be nothing of the kind; some variant of a perpetual motion machine, violating conservation laws and exhibiting a misunderstanding of basic mechanics or thermodynamics. Others misinterpret more esoteric concepts such as quantum mechanics and relativity.

Occasionally, however, the situation is not so clear cut. Inventors may insist that the accepted laws are incomplete or wrong. And in truth many modern inventions, including much of modern microelectronics, would once have been considered to verge on the magical, contravening the science of earlier times. Might an AI come up with an invention which relies on an incompleteness in an existing physical law or even postulate an as-yet unknown one? If it did, could we understand it? And how would the patent system handle a patent application for such an invention? Whilst the building blocks of LLMs are understood (at least by those who develop them), they are essentially a ‘black box’, with the precise reasoning by which they arrive at much of their output remaining mysterious. How then to differentiate hallucination from insight?

Patent systems long ago formalised their rejections of so-called perpetual motion inventions, as being neither capable of industrial application nor sufficiently disclosed so that they may be carried out. But in most cases these ‘inventions’ were relatively straightforward, in concept if not in detail. Now, as AIs become increasingly powerful, it is not beyond the realms of possibility that at some point an AI will make a conceptual leap to an invention which is at odds with present science. What then?

Patent examiners, at least in the UK, have something of an existing framework to follow. Whilst it predates our current AI era and so does not address them directly, it can be pressed into service to act as a bulwark, sufficient until something better comes along.

The seminal case, albeit an imperfect one, dates from nearly two decades ago, when a US company Blacklight Power were pursuing a pair of patent applications. Both applications claimed inventions which relied on a purported new species of hydrogen. Unlike standard hydrogen, this species required the sole electron to exist in an energy state lower than the lowest possible one as recognised in standard physics. Such “hydrinos” were part of a sweeping new theory – the “Grand Unified Theory of Classical Quantum Mechanics” – proposed by Blacklight’s founder and CEO.

The initial patent examiners were unconvinced, refusing both applications. On appeal, a senior examiner was more circumspect, admitting that his understanding of physics was a long way short of what would be necessary to assess the theory on its own merits or to evaluate the voluminous supporting evidence which had been provided by Blacklight. What was clear, however, was that the relevant scientific community had not taken to the new theory; ever since it was first proposed in the early 1990s it had been studiously ignored – which suggested the theory was probably wrong. A further appeal to the high court clarified what has become the current approach.

Patent applications should only be refused if they are “clearly contrary” to well-established laws, not merely probably wrong. Otherwise, providing there is credible evidence that, on the balance of probabilities, there is a “substantial doubt about an issue of fact” which could lead to patentability – and a “reasonable prospect” of the new theory being proved correct when investigated in detail at at a full trial, with expert witness – then the application should be allowed to proceed.

The question of whether, and how much, benefit of the doubt should be afforded the applicant is a finely balanced one. On the one hand, it would be unfair to the applicant if a patent application was refused but the theory turned out to be true; on the other, “it would be completely wrong and against public interest to bestow upon misleading applications the rights and privileges of a granted patent”. The patent system is inherently scientifically conservative, but there is an acknowledgement that there is the danger of of refusing an application which depends on a disputed theory which may subsequently turn out to be correct. The application stage is necessarily “an imperfect tribunal of fact”. Patent examination is not a peer review process. At the application stage, the applicant may need to be given the benefit of the doubt because an incorrect refusal cannot be remedied at a later stage. Only if an invention is required to “operate in a manner clearly contrary to well-established physical laws” is the patent application to be refused from the outset.

In Europe, the EPO has trodden a somewhat similar path, rejecting patent applications which are deemed incompatible with with the generally accepted laws of physics, and yet keeping the door ajar for “revolutionary” inventions which seem, at least at first, to “offend against the generally accepted laws of physics and established theories”. The focus is on practicalities rather than theoretical considerations. To obtain a patent based on such an invention requires the applicant to provide a description “detailed enough to prove to a skilled person conversant with mainstream science and technology that the invention was indeed feasible”.

For Blacklight, the benefit of doubt was not enough. The evidence was unconvincing and the scientific community uninterested. Both applications were referred back to the patent office and finally refused.

The Blacklight cases provide a salutary lesson for both inventors and patent attorneys. We may be entering a new era of AI-assisted inventions, and the patent system may be willing in principle to entertain the idea of inventions which push against or even cross the limits of existing science, but credible evidence is the key. Where examiners may not understand every nuance of an invention, they will look to experimental evidence and in particular whether the new theory has been accepted in the wider scientific community as proxies for assessing “substantial doubt” and “reasonable prospect”. For patent applicants it is important not be to swept along by AI pronouncements. However convincingly an AI may present a seemingly revolutionary invention, and even if no-one seems capable of understanding it, extraordinary claims will always require extraordinary evidence. Whether it will even be possible to collect such evidence if an AI invention is truly beyond our understanding may prove a defining challenge for the patent system.

The UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) has announced proposed fee increases averaging 25% across trade marks, patents, and designs, subject to parliamentary approval. These changes would represent the first adjustment for design fees since 2016, for patent fees since 2018, and the first increase for trade mark fees in nearly 30 years.

According to the UKIPO, the revised fee structure is intended to reflect the 32% rise in inflation since 2016 and to manage future cost pressures that cannot be fully mitigated through efficiency measures or the use of reserves. The additional revenue is expected to support continued investment in digital infrastructure and service quality, while ensuring the UKIPO remains among the most competitively priced intellectual property offices globally.

The proposed average increases are:

- Patents: 33%

- Designs: 24%

- Trade marks: 23%

Full guidance is expected to be published in early 2026 to assist rights holders and applicants whose fees may fall due around the implementation period. Current fees will remain in place until 1 April 2026, when the new fee structure is scheduled to take effect, subject to parliamentary approval.

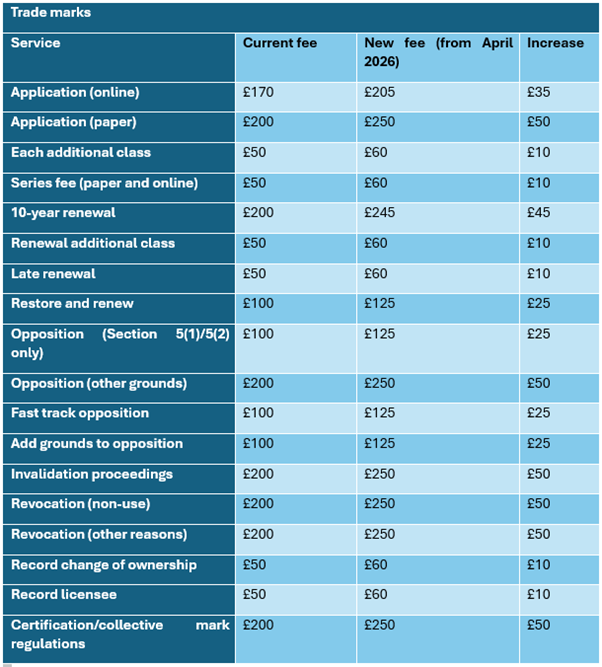

Trade Mark Fee Increase:

Trade mark application fees will rise under the new structure, with the fee for filing a trade mark application online increasing from £170 to £205, whilst paper applications will rise from £200 to £250.

Renewal fees will see also increases across the board – the fee for renewing a trade mark registration will rise from £200 to £245 for both online and paper applications.

Series trade mark applications are also set to increase from £50 to £60. While earlier reports suggested that series applications may be abolished, the proposed fee increase indicates that they are likely to remain in place, at least for the time being. This means applicants wishing to file a series of trade marks will still be able to do so, albeit at a higher cost, reflecting the broader trend of rising UKIPO fees across all trade mark services and we recommend filing sooner rather than later to take advantage of current rates and to account for the potential future phasing out.

Opposition proceedings will become more expensive, potentially leading to more selective or strategic use of opposition proceedings. The fee for filing a notice of opposition based solely on Section 5(1) or 5(2) grounds will increase from £100 to £125, whilst oppositions on other grounds will rise from £200 to £250. Fast track opposition fees will increase from £100 to £125, and the fee for adding grounds to an opposition will rise from £100 to £125.

Applications to start invalidation proceedings will increase from £200 to £250, whilst applications to revoke a mark for non-use or other reasons will also rise from £200 to £250.

The increases in opposition, invalidation, and revocation fees mean that parties seeking to challenge a trade mark, or defend against a challenge, will face higher upfront costs.

The table below outlines the current fees alongside the proposed increases:

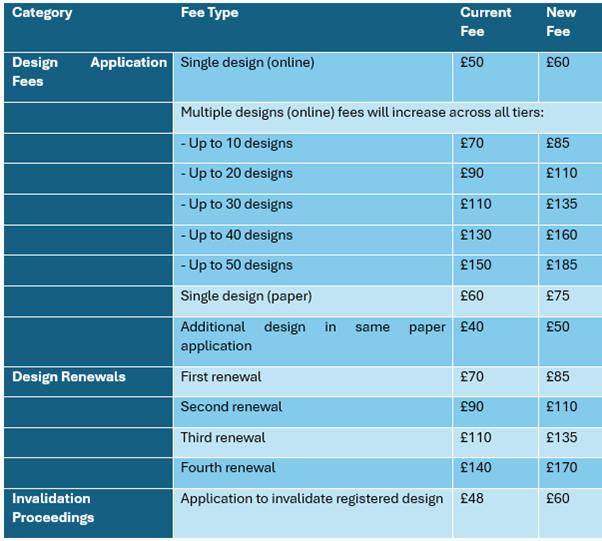

Designs Fee Increase:

The upcoming increase in UKIPO fees for registered designs will have a range of implications: higher filing and renewal costs will raise the overall expense of maintaining design portfolios, particularly for businesses with multiple registrations. Companies may respond by filing fewer variations, allowing lower-value designs to lapse. Smaller designers are likely to feel the impact most, potentially relying more on unregistered rights despite their weaker protection. While the change could reduce speculative filings and ease administrative burdens, smaller businesses may adjust their approach to registered protection, which could influence innovation patterns across certain sectors. Rights holders should consider filing or renewing designs (if able to) before the fee increase takes effect, reassess the value of their portfolios, and adjust budgets and IP strategies accordingly.

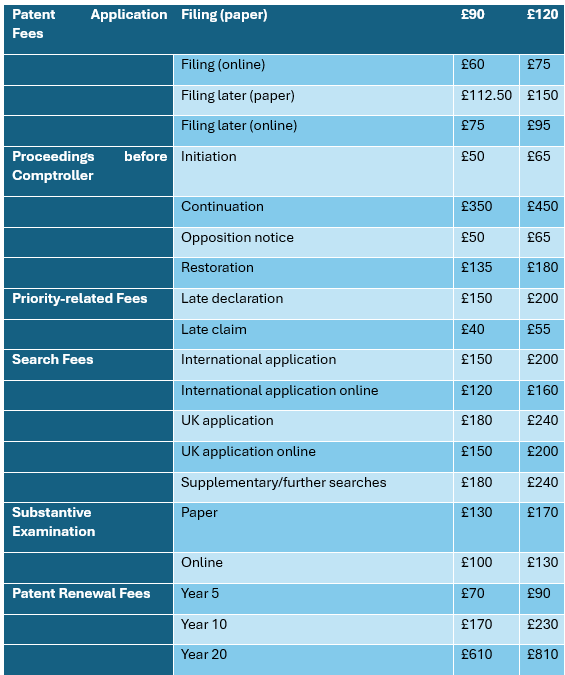

Patent Fee Increase:

The UKIPO is also set to update the patent fee schedule, with all major fees for patent proceedings set to increase. Notably, the total basic fees for filing a UK patent application, including filing, search, and examination, will rise from £310 to £405. In addition, the revised patent renewal fees will range from £90 to £810, depending on the stage the patent lifecycle.

What this means going forward:

Although UKIPO fees will remain at current rates until 31 March 2026, the proposed average increase of around 25% is likely to affect budgeting and the timing of IP activities. Specifically:

- IP Filing strategy: Consider bringing forward planned applications, searches, and filings to take advantage of current fees before the increase. Early awareness allows you to act proactively and protect your brand while avoiding higher costs. We can help assess the impact on your portfolio and provide tailored fee estimates and timeline options.

- Portfolio management: Review the timing of renewals, recordals, oppositions, and cancellation actions that incur IPO fees to determine whether it makes sense to schedule them before 31 March 2026. Businesses that regularly file trade marks, designs or patents should budget for the potential fee rise. The renewal period opens six months before the renewal deadline for trade marks and designs, and three months in advance for patents.

- Decision making/budgeting: This may affect the decision-making process for both potential opponents and respondents, particularly for smaller businesses or individual applicants as they may need to evaluate the merits of a dispute more carefully before proceeding, particularly in cases where the likelihood of success is uncertain. This could alter the overall landscape of IP related disputes in the UK in regard to filing oppositions and invalidity and/or revocation actions. The same is also true for heavy filers and/or oppositions. Internal budgets for the following year will already have (or will soon have) been set and therefore whilst the increases are not necessarily problematic per se, given the number of filings/renewals/oppositions they may file could mean substantial overall increases. Heavy filers/larger businesses will need to factor higher fees into trade mark enforcement and defence budgets, prioritising key cases or exploring cost-effective strategies where necessary.

The UK IPO has updated its payment guide and deposit account terms. You can view the payment guide here and the updated terms here.

If you have upcoming filings or renewals, now is an ideal time to review timelines and budgets and discuss your IP strategy with your patent or trade mark attorney. Our team at Mathys & Squire are committed to delivering exceptional client support and tailoring services to your specific needs. For any questions regarding the UKIPO’s fee increase or assistance with future IP planning, please contact us.

The UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) has proposed fee increases, averaging around 25%, across trade marks, designs and patents, with changes expected to take effect on 1 April 2026, subject to parliamentary approval. These will be the first major adjustments in several years, reflecting rising inflation and supporting UKIPO investment in digital systems and service quality.

However, the new UKIPO fees will still be relatively inexpensive compared to other jurisdictions, maintaining the UK as an attractive territory for securing IP protection.

Patents

All major fees for patent proceedings before the UKIPO will also rise. In particular, the total basic fees for filing a UK patent application (filing, search and examination) will rise from £310 to £405, and the new patent renewal fees will be in the range £90–£810.

Trade Marks

Application and renewal costs will rise, with online filing increasing from £170 to £205 and renewals from £200 to £245. Opposition, invalidation and revocation fees will also increase, potentially prompting more selective enforcement action. Series applications, now rising from £50 to £60, will remain available for the time being.

Designs

Design application and renewal fees will increase across all tiers, affecting businesses with large portfolios. Higher costs may prompt applicants to streamline filings or reassess the value of older registrations. Invalidation actions will also become more expensive.

What Businesses Should Do

Although current fees apply until 31 March 2026, the scheduled increases mean applicants may wish to begin reviewing their IP strategies to:

- Plan budgets early, especially for businesses with high filing volumes.

- Bring filings and renewals forward where possible to secure lower fees.

- Audit portfolios to manage renewals cost-effectively.

- Reassess dispute strategy, as higher opposition and invalidation fees may influence when to challenge third-party rights.

Full guidance from the UKIPO is expected in early 2026. A link to a more detailed article with the full fee increases and implications is provided here.

Gene therapy is revolutionising the field of molecular medicine and the capabilities of therapeutic approaches. Recent developments demonstrate the potential for gene therapy to address some of mankind’s most devastating diseases, unlocking previously unfathomable solutions which could transform people’s lives. As innovation accelerates, strong patent protection is essential to navigate rising IP disputes and safeguard gene therapy advances.

Introduction to gene therapy

Gene therapy is a medical technology which mitigates or eradicates the symptoms of diseases by transferring genetic material to a patient or correcting genetic defects. It can be achieved in several ways.

- Gene replacement delivers a functional copy of a gene to compensate for a defective one, making it especially useful for recessive monogenic diseases.

- Gene silencing reduces the expression of harmful genes, often through RNA interference or CRISPR–Cas13 targeting of pathogenic mRNA.

- Gene editing directly modifies endogenous DNA using tools like CRISPR-Cas9, zinc-finger nucleases, TALENs, or newer base and prime editors. These technologies allow targeted correction or disruption of disease-causing genes with increasing precision.

The genetic material can be delivered to the patient via viral and non-viral systems. For example, viral vectors such as adeno-associated virus (AAV) are preferable for in vivo use due to their safety and tissue specificity. Non-viral systems (such as lipid nanoparticles and polymer-based carriers) usually offer improved safety and flexibility but typically lower delivery efficiency.

Today, gene therapy is applied to an increasingly wide set of diseases. An analysis of patent activity shows that oncology accounts for roughly 32% of the gene therapy market, followed by rare genetic disorders (27%), cardiovascular diseases (15%), and neurological disorders (12%).

Recent innovation in the field

Whilst gene therapy is still predominantly limited to research and clinical trials, with over 250 clinical trials running in Europe and only around 20 therapies on the market, broader clinical adoption is getting closer.

The UK’s Medicine and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) approved the world’s first CRISPR-gene therapy in November 2023 and it is now available on the NHS in England. Named CASGEVY®, the drug (exagamglogene autotemcel) uses CRISPR-Cas9 to alter human stem cells to produce functional rather than defective haemoglobin, treating sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia.

Other advances are also setting the field into motion, such as innovations in delivery methods. Among these, AAVs are emerging as a major force in the gene therapy market. In June this year, Barcelona-based startup, SpliceBio, secured €118 million in a series B finance round to fund their development of AAVs with refined capabilities, able to carry longer genes.

The rapid rise of AI in biomedical research is also transforming how scientists design and test new therapies, including in gene editing. Stanford Medicine researchers have introduced CRISPR-GPT, an AI “copilot” that draws on extensive scientific literature and lab records to propose experimental designs, predict off-target risks, and justify its recommendations.

The patent wars

There are currently over 14,000 patent families related to gene therapy worldwide. Early patents mainly targeted basic delivery mechanisms and methodological approaches, but the focus has grown more specific over time, covering specific disease indications, vector designs and genetic modification techniques.

CRISPR-Cas9 in particular has been the topic of a major dispute over the last decade and the contest for the foundational patent rights is still ongoing. CRISPR-Cas9 was introduced as a programmable gene-editing tool in 2012 by Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, a discovery that later earned them the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Around the same time, Feng Zhang and the Broad Institute demonstrated its use in mammalian cells, triggering a long-running patent battle. This leads to uncertainty and legal risks which impede those who wish to use CRISPR.

CVC

In Europe, one of the two leading CRISPR patent portfolios is held by the team behind the Nobel-winning discovery, collectively known as “CVC” (the University of California, the University of Vienna and Emmanuelle Charpentier). Their core rights are based on the fundamental patent family originating from parent application EP2800811, along with a series of divisional filings. The patents EP2800811 and EP3401400 (one of the divisional applications in the family) were originally maintained by the EPO Opposition Division, but these decisions were appealed. In its preliminary opinions, the Board of Appeal found that neither patent could rely on the earliest priority date because the earliest priority document failed to disclose the essential PAM sequence required by the CRISPR-Cas9 technology, rendering the claims not novel over the Science publication from the same inventors.

CVC decided to withdraw their approval of the granted texts in 2024, effectively revoking both patents to possibly avoid an adverse final decision that could negatively affect their broader CRISPR portfolio (see our relevant article here). The patent family still includes other active members including EP3597749, EP4289948 and EP4570908, with EP3597749 and EP4289948 already facing opposition. We can expect further disputes as the CRISPR patent landscape continues to evolve.

The Broad Institute

On the other hand, the Broad Institute (together with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard College as co-applicants) also obtained early patent rights in Europe based on the patent family originating from parent application EP2771468. The patent was revoked in 2020 on the basis of intervening art that only became citeable due to invalid priority (in which one of the opponents was represented by Mathys & Squire). In this regard, the Board of Appeal held that a priority claim was deemed invalid if a proprietor was unable to show, when challenged, that the applicants for the subsequent application included all of the applicants for the priority application or their successor(s) in title at the time the subsequent application was filed (see our earlier articles here and here).

Interestingly, the recent decision G1/22 issued by the Enlarged Board of Appeal has significantly relaxed the EPO’s approach to “same applicant” priority. The EBA decided that there is a “rebuttable presumption” that the priority applicants approve of the subsequent applicants’ entitlement to priority, regardless of any difference in names (see our earlier article here). The divisional patents EP2784162 and EP2896697, and the relevant patent EP2764103 were originally revoked by the Opposition Division under similar reasons as with EP2771468, but the Board of Appeal have decided to return these cases back to the Opposition Division as the priority entitlement is now considered valid. Opposition proceedings are ongoing, and it will be interesting to see how these cases ultimately unfold.

Recent developments

Other companies have also been entering the legal battlefield in recent years. ToolGen, for example, filed an infringement suit against Vertex’s CASGEVY® therapy in April 2025 in the UK. The ongoing wave of disputes illustrates that the CRISPR and gene therapy patent landscape remains highly competitive. Thus, securing robust patent protection is crucial for companies seeking to commercialise their technologies.

How to protect innovation in gene therapy

Protecting gene therapy technology in Europe requires an early, well-structured patent strategy.

The foundation of any successful patent strategy is a comprehensive freedom-to-operate (FTO) analysis, which should be conducted as early as reasonably possible in the development pipeline. FTO searching allows innovators to identify third-party patents that may block research or manufacture of a gene therapy product. This is especially important in fields such as CRISPR-Cas systems, where multiple parties hold overlapping rights. An FTO review not only helps avoid infringement but can also inform strategic design-arounds, licensing decisions, and the scope of future patent filings.

Equally critical is the issue of valid priority filing, an area that has been at the centre of some of the most high-profile European disputes in gene editing as discussed above. The EPO is well known to be very strict on added matter, and it extends to the assessment of priority validity. The priority filing should include all essential features of the invention and the way for performing the invention that are later claimed. Omissions can result in the loss of the earliest filing date and, consequently, exposure to intervening prior art. Although the recent decision G 1/22 appears to have relaxed the “same applicant” priority rule in Europe, the underlying requirement of adequate technical disclosure remains stringent and fundamental.

Patent drafting

When drafting the patent application itself, a successful strategy typically involves pursuing multiple categories of claims. For gene therapy inventions, this may include:

- Composition of matter claims for the drug product, which might include specific nucleic acid, Cas enzymes, engineered cells, viral vectors, lipid nanoparticles or other delivery vehicles

- Sequence-specific claims for novel nucleic acid sequences

- Medical use claims for using the gene therapy product as a medicament or to treat specific diseases.

- Formulation claims for the specific solutions, buffers or excipients used to stabilise and deliver gene therapy components

- Dosage regimen and administration-route claims for optimised therapeutic windows and dosing approaches

- Manufacturing and process claims for nucleic acid production, cell-expansion protocols, vector-production methods, or purification steps involved in the production of the gene therapy product.

In view of the complexity of gene therapy patents, it is important to seek professional support. The application must be drafted effectively to secure appropriate breadth of protection, while also facilitating a smoother path to grant.

SPCs

Finally, as products approach regulatory approval, innovators might also consider Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs). SPCs extend protection for medicinal products beyond the standard 20-year patent term. This compensates for the time lost during regulatory review. Gene therapy products authorised in the EU may be eligible for SPC protection, provided they meet the regulatory and patent linkage criteria. Our professional team can guide applicants through SPC strategy and the application process (see here for further information).

Gene therapy is advancing rapidly, but its patent landscape remains complex and highly competitive. Careful strategy including strong priority filings, thoughtful claim drafting and early FTO analysis is essential. Robust IP protection allows innovators to focus on advancing therapies rather than defending their inventions.

Three Mathys & Squire Partners, Anna Gregson, Dani Kramer, and Martin MacLean, have been recognised in the 2026 edition of IAM Strategy 300 Global Leaders.

The guide acknowledges those that have showcased their strategic expertise in IP, which has been recognised by clients and colleagues across a range of sectors. Those that have been selected to feature in the prestigious directory have earnt their place through their consistently exceptional work and industry knowledge.

IAM says: Anna Gregson is a recognised leader for strategic IP advisory, leveraging her deep technical expertise in biotechnology to deliver specialised guidance across diverse sectors, including plant biotechnology and diagnostics. Her approach ensures that clients’ IP portfolios are not only technically sound but also commercially resilient.

IAM says: Dani Kramer is a seasoned expert in internet television, software, and AI, with specialised knowledge in semiconductor devices and communication technologies. His career includes securing key patents in the internet television space and managing a portfolio of standard-essential HEVC MPEG patents, underscoring his impactful contributions to this field.

IAM says: Martin MacLean is a distinguished legal practitioner with a robust background in biotechnology and intellectual property. With over 100 EPO hearings under his belt and a remarkable success rate of approximately 90%, he excels in areas such as protein therapeutics, antibodies, and vaccines.

We would like to express our thanks to every client, contact, and peer who dedicated their time to engage in the research process.

The full 2026 edition of the guide is available here.

Partner Samantha Moodie and Associate Clare Pratt have been featured in Life Sciences IP Review and Aesthetic Medicine providing commentary on the increased use of biotherapeutic molecules in the cosmetics industry, following from their own two-part article series.

In the article, they provide insights into the number of international patent applications for ‘bio-cosmetic’ products from 2020 to 2024, highlighting this growing trend and the close relationship between innovation and intellectual property.

They also share expert guidance on how best to utilise IP in this increasingly competitive industry, including best practice advice on drafting ‘use’ claims for cosmetics containing biotherapeutic molecules.

Read the first and second instalments of their related article series titled ‘The Line Between Beauty and Therapy’ in the relevant links.

Read the extended press release below.

Patent applications for ‘bio-cosmetic’ products have doubled to 12,130 in 2024 from 6025 in 2020, says leading intellectual property law firm Mathys & Squire. Bio-cosmetics are a rapidly growing market of consumer cosmetic products containing biological molecules that promote tissue regeneration and repair.

The number of bio-cosmetic applications also grew 9% to 12,130 from 11,130 last year.

Biological molecules, previously used in complex medical procedures, are increasingly finding novel and unique applications in cosmetics aimed at consumers. Examples include:

- The use of stem cell extracts in high-end anti-aging, scar reduction and hair restoration products

- DNA repair enzymes, including genome-editing enzymes, used to correct UV damage in skin cells

- Stimulating collagen production in the body to delay signs of aging

- Exosomes carrying bioactive cargo such as proteins, peptides, lipids, RNA, and DNA used to restore skin volume, rejuvenate the skin and reduce wrinkles.

- Polynucleotides (long chains of nucleotides derived from DNA or RNA) used in high-end cosmetics to promote tissue repair, increase hydration, and improve skin elasticity.

Samantha Moodie, partner at Mathys & Squire, says, “These innovations were previously developed for use in complex medical procedures. However, innovation in the cosmetics industry has begun to use treatments which harness the body’s own biological pathways to boost skin repair and regeneration.”’

“Carrying out research and development in the cosmetics industry can be costly, especially when developing cutting-edge technologies. Patents play a crucial role in helping companies recover these investments by protecting their innovations – as well as helping firms maintain their competitive advantage.”

“The strong uptick in patent fillings shows that cosmetic companies are increasingly looking to the patent system to safeguard their inventions.”

The use of biological molecules in cosmetic applications are a “grey area” between traditional medical and cosmetic uses – careful patent drafting is required to avoid patent law exclusions.

Mathys & Squire add that careful drafting of patent applications, particularly the claims, is required when covering bio-cosmetic technology that often straddles the line between medical and cosmetic applications.

Samantha Moodie says, “Often cosmetic companies have to rely on patent applications that cover a new and innovative use of an already known biological molecule for cosmetic treatment.”

“Uses that have a medical or therapeutic effect are considered unpatentable by many patent offices (such as the European patent office), whereas purely cosmetic uses are allowable.”

“This means that cosmetic companies need to carefully consider the information and data provided in their patent applications as well as the precise language in their cosmetic use claims to avoid unintentionally falling within the scope of patent law that excludes patents for therapeutic or medical uses.**”

Mathys & Squire recommend that companies seeking to protect a new and innovative cosmetic use of a bio-cosmetic product should:

- use clear language to define the “cosmetic” and “non-therapeutic” effects of the product so as to avoid covering any unintended therapeutic or medical applications;

- avoid including statements in the description that relate to or describe any alleged therapeutic benefit of the cosmetic molecule; and

- define the intended user of the bio-cosmetic product as a “healthy individual” to avoid encompassing medical treatment of an unhealthy or sick ‘patient’.

Samantha Moodie adds that, “In some circumstances, it may even be possible to cover cosmetic and therapeutic applications in the same application when a bio-cosmetic product has distinguishable cosmetic and therapeutic effects.”

“In this scenario, a clear definition of the diseases that can be treated should be included alongside data that demonstrates the intended therapeutic effect. In addition, user groups relevant for the cosmetic use and separate data demonstrating the cosmetic effect should also be included.”

*Containing biological molecules such as stem cell extracts, exosomes, polynucleotides, collagen and endonucleases

**Article 53(c) of the European Patent Convention states that patents cannot be granted for methods treating the animal or human body by surgery or therapy, or for methods of diagnosis practiced on the animal or human body.

On the 13th of November, author Ruth Leigh came to our London office in the Shard to join us for this month’s book club and give a talk about her career journey.

Ruth previously worked at Mathys & Squire as one of our support staff and we are pleased to see the success she has achieved following her time here. She has published seven books, including her main book series revolving around the life of the main character, Isabella M. Smugge, an influencer who has just moved to the countryside from London.

We had the opportunity to speak to Ruth about her journey as an author, as well as to look back at her experience at the company twenty-five years ago. In the interview, she looks at how the firm has evolved, highlighting the importance of diversity and inclusion, and shares how her rewarding her time at Mathys & Squire was, putting her in good stead for the rest of her career.

To start things off, can you give us a brief introduction?

These days I’m a full-time writer, but I only started that career full-time in 2022, so it’s still quite new. But I’ve been a freelance writer since 2008. I’ve had an interesting range of careers, looking back. I like to challenge myself, so I’ve done lots of different things.

I’ve been writing fiction since 2021. So far, I’ve written four funny, contemporary books about a TikTok and Instagram influencer, and I’m writing the fifth in the series. I’ve also written a collection of short stories around minor characters in Pride and Prejudice, a poetry book and my latest, a selection of my blogs from 2019-2023.

How long did you work at Mathys & Squire and what did you do?

I came to Mathys & Squire in 1998. Before that, I was working for the Head of Department of Psychology at UCL and it felt like it was time to take a leap. I went to an agency and the job supporting Paul was the first one that came up. I’d never worked in the private sector, and I didn’t know anything about law, but I was used to being in a supportive PA role to quite important people, so it seemed like an obvious progression.

Back then, we were all in one quite small office. I was doing admin work for Paul, but very quickly we started doing other stuff as well. Recruitment was very low key at that time, and rather one-note, so with his encouragement, I added the job of recruitment for Mathys & Squire to my list. I’m delighted to see that some of the staff I helped to recruit are still with the firm. One of our biggest clients was involved in a huge court case while I was there too, so a lot of my time was spent helping with that.

In terms of recruitment, I was very keen to make it more diverse. We were already seen as one of the more go-ahead patent firms, but more diversity was needed. Throughout my time there, I learnt a lot and met some great people, and it was hard work, but I am proud of the fact that by the time I left it looked very different from when I arrived.

In 2003, I was expecting my first child and became a consultant recruiter, working from home. That wasn’t a thing in 2003, so I was breaking new ground there as well.

What was your favourite part about working at Mathys & Squire?

I would say the social life. Our team ended up as quite a big group, so when we managed to get out and about (usually on a Friday evening), we used to have such a good time and I’m still in touch with some of them now, which is lovely.

I do love a challenge and, at Mathys & Squire, every day there was a new one and it really helped me grow positively as a person.

What motivated you to change to a career in writing?

It’s what I’ve always wanted. Apparently, when I was a little child, if anyone said to me, “What are you going to be when you grow up, Ruth?” I would always say, “I’m going to be a writer.” And I think it’s interesting how I worded it. I didn’t say, “I quite fancy being a writer,” or “I might be a writer;” I always said, “I’m going to be a writer.”

And I read all the time. I mean literally all the time. I’d read 15 to 20 books a week if work didn’t get in the way, that’s just my thing. It was the one subject I was naturally good at so it made sense to think that writing would be my career.

My early life wasn’t very happy. When I was 18, I ran away from home to Exeter and I thought, “Ruth, other people have dreams, but that’s not for you. Crush it underfoot and just get on with living your life, that will have to do for you.” So, I put the idea of being a writer to one side and though I would never come back to it again.

I’m glad I did things the way I did and that I didn’t plan it all out, because everything I have done has fed into my writing, including working at Mathys & Squire. I think in book five I’m going to make one of the couples my heroine knows patent attorneys. Why not?

How would you summarise the books you have written?

The main character is called Isabella M Smugge (her name spells out “I Am Smug.”). When I wrote the original blog about her, it was just for fun, creating this ludicrous woman inspired by people I’d seen on social media during lockdown. I’d see these women who were bragging about living their best lives and making banana bread and doing Joe Wicks every morning and I was so sick of it.

I created this character who lives in an incredibly privileged bubble: lots of money, perfect husband, perfect children, perfect house, babbling on Instagram and TikTok about her wonderful life. But I knew that couldn’t be the whole story. So, when I sat down to write the first book, I thought, right, she’s going to have to move out of London to a little village in Suffolk.

She’s narrating it, but she’s an unreliable narrator. She’s telling you how perfect her life is and how everyone loves her, but that’s not the case, and you start to see it through somebody else’s eyes and the cracks start to show. She changes throughout the books, but not too much, because I’m not a fan of books where someone starts off absolutely horrible and by the end, they’re everyone’s best friend. That’s not how it works. Isabella is a lot nicer, but she is still a snob by the time we get to book four.

What is the worst and best part of being a writer?

The worst part is the self-doubt – when you sit there and look at a blank screen and think, “Ruth, you’re a complete fraud. What makes you think anyone’s going to like your stuff?” You spend so much time by yourself, sitting with your own company, and those voices come in and that is hard.

The best bit is when you meet someone or you get an e-mail from a reader telling you that they loved your book and that it touched them. It really matters to me that I can make someone’s life better. People often write to me to say that they’re in a bad place, but that my books are really helping them.

Do you think there are any similarities between your work when you were at Mathys & Squire and your work now?

I’ve never thought about that before, that’s a great question. I think that I often do difficult things in my job now – things that I thought I never could, such as going into a classroom full of 15-year-olds to deliver an inspirational workshop. I can see them thinking, “Great, another boring middle-aged woman banging on about something we hate.” But within five minutes I’ve cracked them. It’s going in and doing something that no one thinks you can do, and that’s what it was like at Mathys & Squire. Within my team, we were doing things we’d never done before, and we were looking at things which seemed unachievable or stupid to even try and trying anyway.

Did you bring anything you learnt whilst working at Mathys & Squire into your career as a writer?

I think it taught me perseverance. I already thought outside of the box, but it increased that quality.

Finally, we can’t end this without touching on the intellectual property side of things. As a writer, copyright protection plays a significant role in what you do. Did you find that you had more knowledge going into it about copyright after working here?

That’s a very interesting question. Yes, it did help me. When I wrote the novels, I was really careful.

With my Issy Smugge book, I work closely with my publisher, who has a set of house rules. When I co-founded a small press and published the other three books through them, no one was telling me what I could write. I had to really think about that, particularly with the Jane Austen book, because I had to know about the law on intellectual property, copyright and public domain. If an author has been dead for seventy years, you can use their words, but there’s something called fair use, so you can’t just quote an entire chapter, because that’s not fair.

Quite often when I’m working with other authors, they’ll ask me questions like that and I’ll find myself talking about IP, and they say, “Wow, how do you know about that?”

I was driving my teenager daughter to college the other day and she was asking what I used to do, so I started describing Mathys & Squire. And I told her about our slightly eccentric client who used to come in every two years with crazy inventions. She was slightly in disbelief that that’s what I used to do. “You did science stuff, Mum? You?” She had a point. I don’t really do science.

I once heard someone say that the patents and trade mark world is like a secret profession. If you say you work in a law firm, everyone knows what you mean. But the minute you mention patents and trade marks, people have no idea what you’re talking about. It’s niche. So, knowing what I knew about trade marks and copyright and inventive step has actually really helped because I’ve not fallen into the pitfalls that other authors sometimes do.

What advice would you give to an artist, whether they’re producing physical art, books or music, on protecting their creation?

You have to check that you’re not infringing copyright. One of the things that’s key in our industry is that you cannot legally quote song lyrics in your books. I got round that, but I did cause my agent some alarm, because I made up a band which appeared in my third book. The editor said, “ Ruth, you can’t do that,” but I explained that it was fine as I invented the band and their back catalogue (one of their songs will be trending on TikTok in book five).

We would like to thank Ruth for taking the time to come back to Mathys & Squire. Mathys & Squire would not function without our support staff, from the people here now to those that have gone but left their mark, and Ruth is just one example of the talent and individuality which we are proud to embrace here.

We are delighted to be the Forum Partner for ELRIG’s UK Forum “Outside the norm”, an event at the University of Warwick, Coventry, exploring engineering biology for drug discovery.

Partner Martin MacLean and Managing Associate Lionel Newton will be representing the firm at ELRIG’s UK Forum “Outside the norm”, taking place on the 13th of November.

Lionel Newton will be delivering a talk that explores how strategic intellectual property (IP) management underpins success in the advanced therapeutics sector. From early-stage spin-outs to clinical development and eventual acquisition, ventures that proactively build and evolve their patent portfolios are best positioned to attract investment, secure partnerships, and sustain competitive advantage. Drawing on real-world experience, including a brief case study, the session highlights how a well-planned IP strategy not only protects innovation but also drives commercial value throughout the therapeutic development.

About ELRIG

ELRIG is a not-for-profit organisation that brings together the global life science and drug discovery community through free-to-attend events. With a network of over 12,000 professionals, it is dedicated to promoting inclusion and accessibility whilst encouraging innovation across the sector. This event will highlight the use of synthetic biology and engineered biological systems in accelerating drug development, discovering new classes of medicines and unlocking previously undruggable targets.

Please reach out to our team if you are interested in arranging a meeting.

For more information on the event, visit the website here.

IPSS Electra Valentine has co-written an article in response to Black History Month, discussing the notion of ‘professionalism’ at work and how we must separate it from Eurocentric standards.

The article examines the discrimination against Black professionals ingrained in what we deem acceptable and ‘smart’ in the workplace, such as attitudes towards natural Black hair, emphasising the importance of allowing and embracing authentic presentation. It highlights that any rules regarding appearance for client contact or formal settings should be limited to reasons of safety, hygiene or product integrity, not style or taste.

The article also features a quote from IP Support Manager at Mathys & Squire, Christine Youpa-Rowe, outlining our firm’s commitment to the Halo Code. The Halo Code is a statement on Mathys & Squire’s stance against discrimination towards Afro hair and an acknowledgement of our staff’s right to embrace all Afro-hairstyles.

You can read the full article here.

Partner Claire Breheny has been featured in ‘New non-alcoholic cocktail brands rise by 19% in two years’ by The Morning Advertiser, ‘Sober curious: How no and low alcohol drinks are redrawing legal lines’ by FoodBev Media and ‘Non-alcoholic cocktails trademarks surge 19% in two years’ by MCA.

In the articles, Claire provides commentary on the growing consumer interest in non-alcoholic beverages which is driving innovation and investment in the industry, as well as shaping trade mark filing activity.

Read the extended press release below.

The number of new alcohol-free cocktail brands being launched in the UK continues to rise with UK trade mark filings for non-alcoholic cocktails jumping 19% in two years to 515 from 433, according to Mathys & Squire, the intellectual property (IP) law firm.

This growth reflects how companies are prioritising alcohol-free product development to meet strong demand from Generation Z consumers seeking healthier, socially-inclusive drinking options.

During the same period, the number of new gin trade marks filed fell 9% from 642 to 582, while rum filings decreased 5% from 662 to 627, demonstrating changing consumer preferences toward alcohol-free alternatives.

However, whisky trademarks moved in the opposite direction, growing 7% from 714 to 761. New trademarks are being filed in order to market more budget whisky brands, with shorter ageing periods, without jeopardising existing upmarket brands.

The surge in non-alcoholic cocktail filings reflects a broader growth in innovation and investment across the broader alcohol-free drinks segment.

Leading companies, including Diageo, are investing significantly in new product launches, alongside marketing campaigns and sponsorships, to capture growth in the expanding alcohol-free market.

Claire Breheny, Head of Trade Marks at Mathys & Squire, says:

“The increase in non-alcoholic cocktail trademarks shows how alcohol free alternatives are being developed for all the main drinks categories.”

“Health trends and Generation Z drinking habits are transforming industry innovation priorities and investment strategies.

“Businesses that fail to innovate effectively risk losing out on one of the fastest-growing and most dynamic market segments in the global drinks industry.”