Data and commentary provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in an article by The Nutraceutical Business Review, providing an update on the growth of the nootropics market.

A condensed version of the article is available below.

The global nootropic market is set to reach a value of $6.61 billion by 2026 at a compound annual growth rate of 13.7%, according to some projections. The term ‘nootropic’ describes a broad category of nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals offering cognitive function benefits. Caffeine is the most recognisable nootropic, but there are other examples that consumers will ingest on a regular basis, such as L-theanine (found in black and green tea), anthocyanins (found in blackberries), nicotine and creatine.

The increasing popularity of nutraceuticals, and particularly nootropics, appears to reflect consumers taking a more active approach to their health and wellbeing, as a consequence of evolving lifestyle choices, increased health awareness, and a shift toward a preventative healthcare paradigm.

Why are nootropics so popular?

Nootropics have established a wide and cross-generational appeal as individuals seek to ‘biohack’ their cognitive function with supplements and functional foods.

Competitive gamers and ‘eSports’ professionals are increasingly using nootropics to improve gaming performance. However, there is also a growing use of nootropics in sports nutrition by athletes, particularly those involved with team sports requiring swift decision making, motor control, coordination and timing. Nootropic sports drinks formulated with herbal nootropics for instance already exist and are marketed as helping improve focus, as well as energy levels.

It is not surprising that nootropics are also being marketed towards working professionals wanting to be more productive and stay focused, as well as to older generations wishing to retain mental acuity and stave off any mental decline.

Innovation driving popularity

Another notable reason for the increasing popularity of nootropics is that they are becoming more convenient and appetising to consume. Nootropic supplements are readily available in the form of chewable gummies, and in a variety of flavours, for those who have ‘pill fatigue’. In addition, nootropics are becoming increasingly prevalent in functional foods and beverages that can be integrated more readily into people’s existing routines. For example, there are nootropic snack bars, protein bars, performance drinks, stimulant-free functional beverages, and even adaptogenic coffee blends and alcohol-free nootropic mocktails.

The growth of personalised/individualised healthcare has also infiltrated the nootropics sector, as innovators have started offering personalised/individualised nootropic formulations determined by algorithms that take consumers’ responses to lifestyle questionnaires and convert them into a tailored formulation.

Protecting innovation

Unsurprisingly, the nootropics market is a hotbed for innovation, as companies fight to distinguish their products from those of their competitors and capitalise on the shift in consumer trends. Branding and marketing strategy play a significant role in the commercial success of such products, but innovators are also recognising the value in protecting their innovations through patents. New European patent applications in the ‘food chemistry’ category increased by 6.1% in 2021 over the previous year, suggesting that the innovation seen in the sector is translating to increased numbers of patent filings year on year.

As with other food chemistry products, there are numerous options for protecting technical innovation underpinning nootropic products through patents. For instance, protecting a new composition or formulation of ingredients (including, for example, a synergistic ‘stack’ of actives), and uses thereof, is often the most desirable protection sought by applicants.

There are also other patent protectable innovations relating to improvements in product bioavailability, organoleptics, shelf life, or for overcoming challenges to meet consumer preferences (e.g. to be derived from sustainable sources or to be vegan). There are also patentable innovations relating to extraction techniques of natural products and processing methods for producing a food product having, for instance, particularly high purity or particularly high active concentration, as well as new uses of known nutraceuticals that innovators may seek to protect.

Use claims (patents) at the EPO – where things can get more complicated

Patenting nootropic products, or indeed any form of nutraceutical product, does not come without its challenges. The European Patent Office (EPO) does not, for instance, distinguish between a pharmaceutical or a nutraceutical product (for example, a functional food with a purported health benefit), which can be problematic when it comes to claiming the use of a nootropic product.

The EPO does not allow claims to methods of treatment of the human or animal body by surgery or therapy and many readers will know that claims relating to a medical use must be formulated in a specific manner to avoid such exclusions to patentability at the EPO. Nutraceutical products which may have a health benefit can fall into a grey area where they might not be intended for the treatment of a particular disease, but a claim to their use might be considered to constitute a method of treatment and therefore, fall foul of the exclusions.

Non-therapeutic / cosmetic method claims are allowable at the EPO, however, the non-therapeutic use must not be “inseparably associated” or “inextricably linked” with a therapeutic use – which is not always clear. Some cosmetic methods can also help prevent disease. One can, for instance, imagine how there might be confusion if a nootropic product may improve cognitive performance in a healthy subject, but may have a therapeutic effect in a subject with a cognitive disorder.

Helpfully, a relatively recent EPO Board of Appeal decision T 1916/19 has clarified that a non-therapeutic method is allowable, so long as there are “realisations” of the claimed method that are purely non-therapeutic. Thus, in the case of the EPO, it seems that there are signs of a permissive approach to the assessment of non-therapeutic method claims, which is likely to be particularly welcome to nootropics innovators and the nutraceutical sector more widely.

Health claims (labelling) in Europe

Innovators in the nutraceutical sector must also navigate EU and UK regulation when seeking to market their innovative products. EU Regulation on food labelling and equivalent UK regulation prohibits labelling of foods with assertions that they prevent, treat or cure human diseases, which is understandable since they do not go through the same regulatory approval as medicinal products do. However, the regulation does allow assertions that a foodstuff “reduces the risk” of disease, provided it is listed on the EC Register of acceptable health claims.

If a nootropic or a nutraceutical product, cannot be marketed in the EU or UK as being useful for preventing or treating a human disease, how much value is there in granted patent claims directed to a medical use of a nutraceutical product? The answer to that is not so straightforward, but it certainly means that applicants should be considering ways to maximise the benefit of such claims, for instance by mirroring the allowable labelling language by referring to “reducing the risk of a disease” in the patent claim itself.

Summary

The nootropics sector is a particularly fast-growing branch of the nutraceuticals market which seems set to cement itself in the public consciousness in the future, if it hasn’t already. It is clear that nootropics have a wide appeal to consumers and the innovations in the sector continue to mean that there are more options available for consumers to integrate nootropic products into their routine, and inevitably more options to ‘biohack’ in a personalised and individualised fashion. Whilst there are certain hurdles for innovators to market such products, it is apparent that they can enjoy the full remit of patent protection for their innovations within the sector, at least as far as Europe and the UK are concerned.

Data provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in an article by Managing IP analysing the increase in demand for free-from foods and the subsequent surge in legislation.

An extended version of the release is available below.

Increased consumer demand for free-from food and drink products, such as non-dairy milk, low or no-alcohol and meat alternatives has seen a raft of new products hit the market in recent years. This change in consumer demand is driven by health concerns and increasing food sensitivities, as well as concerns over the impact of traditional meat and dairy products on climate change, and even long-distance transportation.

Given the huge potential for revenue growth in this market, which is expected to hit $1 trillion by 2026, established free-from brands, new entrants and makers of more conventional products will be fighting for market share. Unilever has announced plans to grow its plant-based meat and dairy products business five-fold to €1billion by 2027.

In an increasingly hotly contested space, brands such as Oatly and Impossible Burger have resorted to legal action over alleged breaches of their intellectual property in a bid to protect their market share. As the market grows, what considerations do brands need to take on board when pursuing litigation?

Assessing potential risks to your IP

On 9 March 2022, Impossible Foods Inc started infringement proceedings against Motif FoodWorks based on its US patent, US 10,863,761. According to Impossible Foods, when starting out, they had a team of researchers analysing which biological molecules make meat look and taste the way it does. As a result, it was discovered that a hemoprotein molecule, soy leghemoglobon (LegH), could be incorporated into plant-based products to provide meaty aromas and create the appearance of “bleeding” in a burger, similar to that of traditional beef products. Impossible Foods state that this molecule is a key ingredient in its products.

The action brought by Impossible Foods centres around Motif’s sale of HEMAMITM – a bovine myoglobin composition which Motif’s website states “tastes and smells like meat because it uses the same naturally occurring heme protein”, along with burgers produced containing the HEMAMITM molecule. Impossible Foods claim that Motif directly infringe their patent (through the sale of the burgers) and indirectly infringes their patent through the sale of HEMAMITM – as Motif are considered to “actively encourage its business partners to make, sell and/or offer for sale the infringing burger”.

Claim 1 of US 10,863,761, refers to “a beef replica product, comprising:

- a muscle replica comprising 0.1 %-5% of a heme-containing protein, at least one sugar compound and at least one sulfur compound; and

- a fat tissue replica comprising at least one plant oil and a denatured plant protein, wherein said muscle replica and fat tissue replica are assembled in a manner that approximates the physical organization of meat.”

In response, Motif FoodWorks has now filed a petition with the USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board to request that the validity of the Impossible Food’s patent be reviewed. It would appear that Motif’s arguments are that the use of heme proteins in meat substitutes was known prior to the filing of this patent.

Motif’s actions in the circumstances are unsurprising and it is essential for companies to critically assess their own IP before commencing any form of contentious action. This ensures companies are aware of and can prepare for any potential attacks against their IP once proceedings begin.

Assess potential damage to reputation

In the June 2021 UK High Court case, Oatly AB/ Oatly UK Limited asserted that Glebe Farm Foods Ltd’s oat milk product, PureOaty (shown below,) infringed five of its registered trade marks, including three word marks (OATLY, OAT-LY! and OATLY) and two device marks (a blue OAT-LY! carton mark, shown below, and a grey OAT-LY! carton mark).

However, the judge dismissed this case stating that “there is no likelihood of confusion between the PUREOATY sign and carton and any of the Oatly trade marks”.

The decision to bring proceedings against Glebe Farm Foods (a significantly smaller competitor), resulted in negative publicity and a social media backlash with respect to the Oatly group. In particular, Oatly received media commentary accusing it of hypocrisy, often based around its 2020 investment from private equity fund Blackstone, which has been linked to deforestation.

While Oatly may have felt it had no choice but to take action against Glebe Farm, as failing to defend trade marks could open the door for other brands to enter the marketplace, the ultimate decision of whether to pursue a third party needs to be weighed up carefully against any potential long-term reputational damage in the marketplace.

A further dispute, relating to the ownership of US 11,058,137, is ongoing between two meat alternative startup companies, Meati Foods (previously Emergy) and The Better Meat Co. Co-founders of Emergy.

Tyler Huggins and Justin Whiteley claim that, while conducting research at the U.S. Department of Energy’s UChicago Argonne National Laboratory (“Argonne”) in Illinois, they developed a new mycelium cultivating process (mycelium being the vegetative part of a mushroom consisting of a mass of branching, fibrous filaments called hyphae), which allowed the cultivated material to maintain a fibrous filament structure. Dr Huggins and Whiteley then went on to assess the use of this material as a meat alternative product. During this time Augustus Pattillo assisted in this research and had access to relevant confidential information before gaining employment at The Better Meat Co. Meati have accused The Better Meat Co. of basing their patent, US 11,058,137, which names Mr Pattillo as an inventor, and their filamentous fungi-based meat alternative product, ‘Rhiza’ on misappropriated trade secrets, as well as proprietary and confidential information belonging to Meati Foods. Meati Foods has requested that US ‘137 be assigned to their company. In response, The Better Meat Co. asserts that the action is simply an attempt to bully a less funded rival within this field. The issue of who owns such information will likely be key as well as the legal agreements and recorded information available from that time.

Given the rapid growth and potential size of this market, it is quite clear that the potential IP clashes will grow considerably in the coming years. However, given the expense of litigation proceedings and potential issues with respect to brand reputation, consideration should be given to other ways of settling disputes.

Alternative means of dispute resolution

For companies who find themselves embroiled in an intellectual property dispute but would prefer not to proceed down the litigation route, there are a range of options at their disposal which could be cheaper, faster and/or more discrete compared to full-blown litigation. For example:

- Offer to buy a licence: Short-term this may be a cheaper option, whereby firms offer to pay an annual fee to continue to use the contested IP.

- Purchasing IP rights: This can be more costly than licensing, especially up front, but brings the advantage of long-term security.

- Opting for mediation: Mediation uses an independent mediator to try and help resolve disputes without requiring court proceedings. This has obvious advantages for smaller players but may also offer advantages to large corporates too. This is especially the case if the IP which they claim is being infringed is not core to their business and they would like to enforce their rights without investing too much time and money. They may also be more likely to agree to mediation if they are less sure of the outcome.

All companies looking to make their way in the field of no/low products need to have a commercial strategy with a number of options should a third party seek to lay down a challenge.

Companies looking to develop new products and protect new and existing IP in this rapidly growing market should make sure they are as informed as possible on the latest IP law developments. With the right knowledge and expert advice they can ensure their products are indeed free from controversy.

We are delighted to announce that Mathys & Squire has maintained its ranking for the PATMA: Patent Attorneys and PATMA: Trademark Attorneys categories in the 2023 edition of The Legal 500. We are pleased to report that we have had a record number of fee earners individually recommended in this year’s guide.

Patent Partners Chris Hamer, Alan MacDougall, Martin MacLean, Jane Clark, Paul Cozens, Craig Titmus, Dani Kramer, Philippa Griffin and Juliet Redhouse, who have been listed in the guide for a number of years, as well as James Wilding, Sean Leach and James Pitchford, who are all newly ranked, are all featured in the 2023 edition of the directory. Joining our team of Key Lawyers this year is Laura Clews, our ‘extremely competent’ Managing Associate.

Alongside our patent practice, Mathys & Squire’s trade mark team has also been recognised, with Partners Margaret Arnott and Gary Johnston, as well as Managing Associate Harry Rowe, all being individually recommended. Of Counsel Rebecca Tew has been listed in the guide for the first time.

The firm received glowing testimonials for its patent and trade mark practices:

‘The most fortunate development of our business was engaging Mathys & Squire. Highly knowledgeable, professional and excellent value for money.’

‘My experience with the Mathys & Squire team has been outstanding. They are organised, responsive, and dynamic. They ensure they have gathered all of the relevant data by virtue of asking the appropriate questions and extracting information that I may have overlooked or not considered.’

‘The Mathys & Squire team has been able to effectively guide us on all of our queries.’

‘Mathys & Squire stands out above all other firms.’

‘Highly targeted advice and in-depth knowledge of how trade marks work. Holistic advice on manoeuvring through other companies’ rebuttals.’

Aside from the excellent firm-wide feedback we received, our Key Lawyers were also praised by all our clients and contacts.

‘Paul Cozens is my primary contact and he brings a wealth of experience that enables him to get to the key issues very quickly. He is supported by a strong team who always deliver high quality outcomes.’

Our main contact, Martin MacLean, has truly extensive experience in prosecuting patent applications through the whole process from filing to award. His support team are also highly competent. It is a pleasure to work with Martin.’

‘Laura Clews and Jane Clark have always been a delight to work with. They are both extremely competent and pleasant.’

‘Craig Titmus brings dedication, knowledge and humour to our meetings. He clearly has a passion for science and our specific products, delivering assignments with a competitive edge. Craig addresses issues head-on, and delivers quality, in-depth reports even when deadlines are squeezed from 3 months to 3 weeks without notice and without flinching.’

‘I have been working with Alan MacDougall for over ten years. Alan is very diligent in his work and has extensive knowledge and experience in the intellectual property field. He always responds in a timely and accurate manner and has been a reliable partner in my business.’

‘Chris Hamer’s unbelievable ability to analyse complicated concepts incorporating chemistry, physics and mechanical disciplines, and somehow render the interaction clear and easy to read, is outstanding. I can say with total transparency that the strength of our patent portfolio is in good part thanks to Chris.’

‘Margaret Arnott is clearly a deeply experienced and highly knowledgeable trade mark attorney.’

For full details of our rankings in The Legal 500 2023 guide, please click here.

We would like to thank all our clients and contacts who took part in the research, and congratulate our individual attorneys who have been ranked in this year’s guide.

The UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) released a guidance note for the examination of patent applications relating to artificial intelligence (AI) inventions. The UKIPO has confirmed that patents can be granted for AI inventions, given they provide a technical contribution to the state of the art.

Following a period of consultation that ran from 7 September to 30 November 2020, the new guidance note details the requirements of AI technologies to meet patentability criteria. As computer programs are specifically excluded from patentability criteria, the new guidance note and accompanying scenarios provide clarity when seeking to patent AI-based technologies.

The UKIPO defines AI as:

“Technologies with the ability to perform tasks that would otherwise require human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition, and language translation”.

In summary, the new guidance note states that:

- AI patents are available for all fields of technology.

- Whilst mathematical methods or computer programs are excluded from patent protection, when the task or process performed by an AI invention contains a technical contribution, it is not excluded.

- An AI invention is likely to provide a technical contribution if it:

- carries out or controls a technical process existing outside the computer;

- contributes to the solution of a technical problem, external to the computer;

- solves a technical problem in the computer itself; or

- defines a new way of technically operating a computer.

- AI inventions are not excluded if they are claimed in hardware-only form (ie. they don’t rely on program instructions or a programmable device).

- AI inventions are likely to be excluded from patentability if they relate to an excluded item, relate solely to processing data, or are a general improvement on a program or conventional computer.

When considering the patentability of AI technology, focus is therefore placed on the technical contribution the invention makes to the state of the art.

Example scenarios

The UKIPO has also released a series of scenarios concerning AI or machine learning (ML) technologies and whether they meet the criteria for patentability. These scenarios focus on the issue of excluded matter and cover a breath of fields and technologies with worked examples of why each invention is or isn’t excluded from patentability.

Particularly interesting scenarios include the training of a neural network, in which the end result of the process and its intended use can be the deciding factor in whether or not it is excluded from patentability.

For example, training a neural network classifier system to detect cavitation in a pump system is allowed. Such a method involves correlating data pairs with class values to produce a training dataset (wherein each class value is indicative of an extent of cavitation within the pump system) and then training the neural network classifier system, using the training dataset and back propagation.

The fact that this process is reliant on a computer program does not exclude it from patentability, since it provides a contribution which uses physical data to train a classifier for a technical purpose – namely, the detection of cavitation in a pump system. The end result of this training, and its contribution, is therefore technical in nature.

By contrast, active training of a neural network is not allowed. Such a process involves determining areas of weakness in the neural network by comparing confidence levels to a threshold, then augmenting the training data with data related to the area of weakness. For example, a neural network used for detecting animals in pictures may struggle to identify cats, so the specimen data may be augmented with additional pictures of cats. This is more efficient than simply expanding the dataset across all elements.

While this method may result in a more efficient training method for a neural network, it does not itself produce a neural network that operates itself more effectively or efficiently. The mere identification of specific additional training data cannot be said to relate to a technical problem. As such, no technical problem has been solved within the neural network, and no technical effect is produced. A claim directed to this would therefore be excluded as a program for a computer as such.

Additional scenarios may be accessed here, and the guidelines published by the UKIPO are available here.

(C) Naomi Korn Associates & Mathys & Squire 2022. Some Rights Reserved. These case studies are licensed for reuse under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike Licence.

The following case study has been taken from the “Implications of Covid-19 on SMEs – Reassessing the Role of IP in Multiple Sectors and Industries” report written by Naomi Korn Associates and Mathys & Squire Consulting, November 2021. This case study reviews the impact on SMEs (small, medium enterprises) of the COVID-19 pandemic since its appearance in early 2020 through the first quarter of 2021. It focuses on the industries most affected by the crisis and whether intellectual property (IP) and IP management may have helped mitigate its impact through adaptation and change.

Sector overview

During the pandemic, social distancing, and a reluctance to use public transport, resulted in a rise in the use of alternative modes of travel. This has included e-bike hire schemes, such as Lime, and ride sharing platforms like Uber.

Analysis

The pandemic has caused a further shift in the wider mobility market with many companies in this space making significant strategic changes towards ACES (autonomous driving, connected cars, electrified vehicles, and shared mobility). Worldwide, there have been more than 420 partnerships signed and the space has seen significant investment, with startups offering mobility technologies receiving $45 billion in 2020 alone.

Micro mobility modes of transport, including lightweight options such as bicycles, e-scooters, and mopeds have grown significantly during this period, whilst the roll out and investment in autonomous vehicle technology has continued to grow during the crisis and is likely to help in the economic rebound post COVID-19 [1]. This technological shift has resulted in the redefining of car lanes to fit more bikes, scooters, and even autonomous vehicles, as well as government incentives across the globe advocating the use of low-carbon transport modes. Companies such as German Colivery, arising from the Government and Vodafone backed “Wir Versus Virus” Hackathon, have developed an online shopping experience connecting self-isolating people with volunteer delivery drivers, who use software optimised routing and several shopping lists on the same route to ensure maximum efficiency.

A number of companies have also developed e-scooters, including UK based company Ginger, which with the help of Enterprise Europe Network, trialled the scooters in a number of cities in the north of England. Ginger also took advantage of coronavirus-related loans and grants. Several other companies internationally, such as the US-based companies Lime and Bird, have large patent portfolios, which we can expect to see grow over the coming months. With the growth of this market, and the increased demand for this technology, businesses are likely to carve a niche for themselves, seeking to protect their position and their brand through enforceable IP rights, such as patents and trade marks.

The transport sector has clearly demonstrated their IP and its application through joining the Open Covid Pledge. Companies such as Uber, have offered patents relating to safe routes for navigation systems, and real-time resource management, to companies trying to combat COVID-19 through royalty free licences. AT&T have also engaged in the pledge through offering their IP relating to the reduction in travel time of emergency transport.

Localised travel restrictions and fear of infection have increased the interest in private vehicle ownership, with a recent McKinsey study indicating that approximately a third of consumers value access to a private vehicle compared to pre-COVID-19. In the United States, 20% of people who did not own a vehicle prior to COVID-19 are now considering acquiring one.

In addition to this, the pandemic has raised awareness of the human involvement in the logistics industry and has sparked interest in the likely need for self-driving vehicles moving forward. In this context, autonomous vehicles, and autonomous driving technology also saw a substantial push in 2020, partially due to their ability to reduce the risk of infection and avoid physical contact.

The autonomous delivery company NURO, was given permission in the US to operate its vehicles on public roads, accelerating grocery deliveries. NURO has also adapted its vehicles to serve in supplying local COVID-19 hospitals with much needed supplies. NURO, which already had a large portfolio of over 30 patents, has recently partnered with Domino’s Pizza to provide autonomous vehicle pizza deliveries, and we can expect this growth to continue as many of the new innovations arising during the pandemic are protected and published. UK-based Oxbotica, an autonomous driving spinout from Oxford University, notes the potential for autonomous vehicle technology in reducing the spread of the virus, but also for longer term benefits in areas such as mining, port logistics and other industrial applications. As a result of its impact in reducing the spread of the virus, the demand for low-speed autonomous driving technology, such as Baidu’s Apollo, is increasing. To support frontline workers in China, the company has made its Apollo open-source autonomous driving platform and related patents available to companies developing vehicles for carrying out disinfection tasks. By growing its network of companies using its AI heavy IP portfolio, currently most of which is through open licensing arrangements, the company is generating an ecosystem of businesses using its technology to fight the pandemic, while at the same time creating a situation whereby its patent portfolio becomes the standard across a number of fields.

Across the transport sector, electric vehicles, e-scooters and autonomous vehicles offer novel solutions to the problems created during the pandemic, not only in terms of potentially reducing the transmission rate of the virus, but also issues surrounding logistics and cargo transport, where ill staff may seriously affect the ability of these sectors to operate.

[1] Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2020): The circular economy: a transformative Covid-19 recovery strategy

Naomi Korn Associates is one of the UK’s specialists in copyright, data protection and licensing support services.

Mathys & Squire Consulting is an intellectual property consulting team that can support all businesses in capitalising intangible assets.

Naomi Korn Associates and Mathys & Squire Consulting are working in partnership across multiple industries to provide innovative consultancy IP support services.

Data and commentary provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in articles by The Manufacturer and The Patent Lawyer, providing an update on the rapid growth in drone patents that have been granted in recent years.

An extended version of the press release is available below.

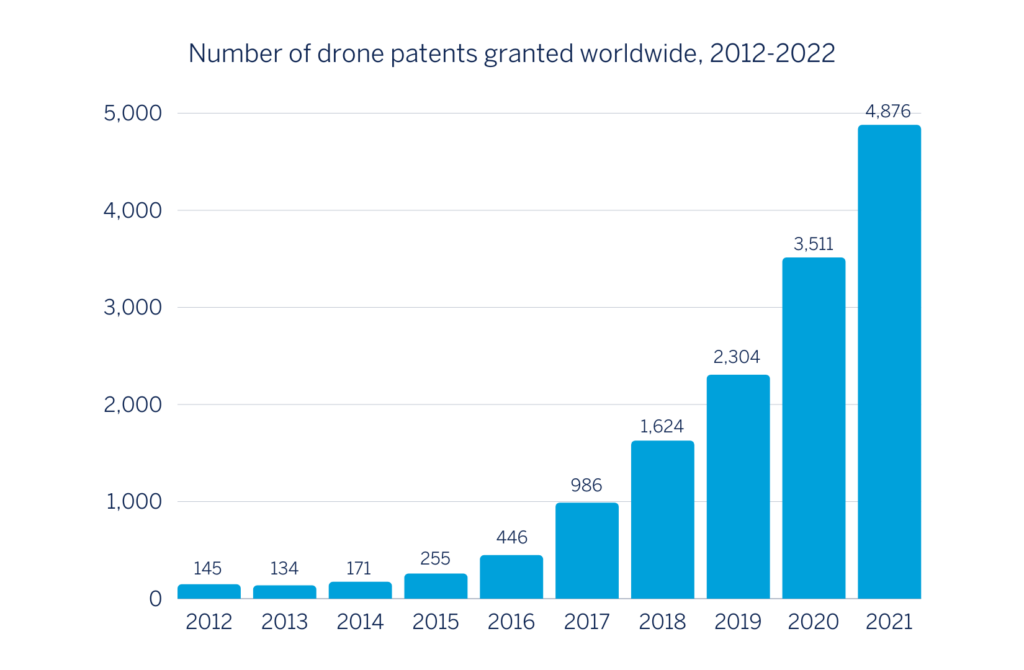

Patents granted for drones worldwide have increased by 39% to 4,876 in the past year*, shows new research by leading intellectual property law firm Mathys & Squire. The figure is up from 3,511 in the previous year and up three-fold from just 446 patents five years ago.

Mathys & Squire says the global drone market is dominated by China. Of the patents granted in 2021, 3,262 (67%) belong to Chinese companies and research institutions. The US trails in second place, with 751 drone-related patents granted in 2021 – 15% of the global total.

Drone technology is being employed across a growing list of sectors, including agriculture, construction, energy, news reporting and delivery of emergency medicine and supplies.

The commercial drone market is predicted to be worth $47 billion by 2029, while estimates suggest the military market could be worth $98 billion by the end of the current decade*. While some of the expected applications in the commercial drone market (such as home delivery services, including fast-food!) have yet to fully materialise, new commercial uses for drones are constantly being developed.

Manufacturers are competing to corner as much of this rapidly growing market as they can by registering patents to protect their often considerable R&D investments.

Andrew White, Partner at Mathys & Squire says: “Drones are increasingly becoming part of everyday life, yet the strong growth in new patents suggests their full potential is still to be realised.”

“Drones are set to play a major role in the global economy in the 21st century. IP in this area is extremely valuable and therefore likely to be hotly contested in the coming years. Companies are spending considerable sums on drone research and will want that investment to be protected with patents.”

Patents related to drone technology granted last year include:

- A fire extinguishing drone for communication wires and other hard to reach infrastructure;

- An unmanned aerial vehicle-based virtual reality touring and sightseeing system;

- A drone-based system for measuring atmospheric pollution;

- A drone-based system for monitoring buildings for cracks and structural weaknesses;

- A drone-based system for pollinating strawberries;

- An amphibious unmanned aerial vehicle for measuring water quality;

- An aerial mask-dispensing machine for use during pandemics;

- A drone-based system to detect oil pollution in water;

- A drone-based system for monitoring the safety of oil and gas pipelines;

- A real-time landslide prediction and early warning system using drones;

- An early warning system for forest fires;

- A drone-based system for filtering factory exhaust gases; and

- An unmanned aerial vehicle capable of drilling blasting holes in rock walls.

*Year ending December 31 2021, Source: World Intellectual Property Organisation

**Source: Fortune Business Insights

***Source: Teal Group

In the latest update on the artificial intelligence (AI) inventorship saga, the legal Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office has now provided their written decision and reasons for dismissal of an appeal that AI should be recognised as an inventor of a European patent.

We have previously covered the decision of the UK Court of Appeal which similarly dismissed an appeal that the very same AI system should be recognised as an inventor of a UK patent, which can be read here.

Whilst many jurisdictions seem to agree with the UK’s and EPO’s position, the South African Patent Office however, was willing to issue the world’s first patent listing with AI as the inventor and the AI’s owner as the owner. Our commentary on this news can be read here.

Background

On 17 October 2018 and 7 November 2018, Dr Stephen Thaler filed two patent applications at the EPO without designating any inventors. In response to the resulting communications inviting the applicant to designate an inventor, Dr Thaler indicated “DABUS” (Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience) as the inventor, with the comment that “the invention was autonomously generated by an artificial intelligence”. Furthermore, Dr Thaler argued that he, as the owner of the machine, had acquired rights to the patent as the employer, followed by a subsequent corrected designation of the inventor asserting that he had derived rights in the invention as the successor in title of the machine by virtue of being its owner.

Both applications were refused by the receiving section on the grounds that: a) designation of a machine as inventor did not meet the requirements of Article 81 and Rule 19(1) EPC, an inventor within the meaning of the EPC must be a natural person; and b) a machine has no legal personality and can neither be an employee of the applicant nor transfer any rights to him.

This decision therefore covers two main topics: 1) whether the ‘inventor’ within the meaning of Article 81 EPC must be a natural person; and 2) to whom do rights within the meaning of Article 60(1) EPC belong if no natural person inventor exists, and how would such rights be transferred.

Main request

The appellant’s main request listed DABUS as the inventor and argued that Dr Thaler had derived the right to the patent as successor in title by virtue of being the owner and creator of the AI inventor.

The Board found the main request to be not allowable because the designation of the inventor did not comply with Article 81 EPC. The Board pointed to the Oxford English Dictionary and Collins Dictionary of the English Language definitions of the word inventor, both of which define an inventor as a ‘person’. There was seen to be no reason to assume that the EPC uses the term in a special way departing from this meaning. When a provision of the EPC 2000 refers to or includes the inventor(s), it uses the terms person or legal predecessor (e.g., Article 60(2) EPC or Article 55(1) EPC), thus, it postulates a person with legal capacity.

The Board felt that there was thus no reason to examine the origin of the right to the European patent, as per Article 81 EPC, second sentence.

Auxiliary request

The appellant’s auxiliary request designated no inventor, instead asserting that the invention was conceived autonomously, and the first sentence of Article 81 EPC thus does not apply. The auxiliary request also included a statement, that Dr Thaler had derived the right to the European patent by virtue of being the owner and creator of the AI inventor.

The Board in fact agreed with the appellant’s argument that the first sentence of Article 81 EPC does not apply in this situation. However, the auxiliary request did not resolve the issue of ownership. Article 60(1) EPC vests the rights in the European patent to the “inventor or his successor in title” as well as deferring to national law in the case that the inventor is an employee. The Board did not agree that being the “owner and creator” of the machine brought the applicant within the rights conferred by Article 60(1) EPC, i.e. the owner and creator is neither the successor in title nor the employer of the machine – in short, a machine has no legal personality and cannot transfer any rights.

This creates a situation where the requirements of Article 81 EPC, second sentence, i.e. the statement indicating how rights are derived from the inventor, cannot be satisfied. Both requests therefore failed to meet the requirements of Article 81 EPC.

Comments

The take-home comment appears to be that a natural person inventor is necessary for the grant of a European patent. Additionally, rights conferred by inventorship cannot subsist in or be transferred from a machine.

This poses a question: should it be possible that a patentable invention within the meaning of Article 52 EPC could be conceived of purely by an AI system? Does this decision rule out patentability of such inventions?

The Board certainly did not rule out the patentability of AI generated inventions per se. Indeed, the Board actually confirmed that the scope of patentable inventions is not limited to human-made inventions, see reasons for the decision paragraph 4.6.2:

“Firstly, under Article 52(1) EPC any invention which is novel, industrially applicable and involves an inventive step is patentable. The appellant has argued that the scope of this provision is not limited to human-made inventions. The Board agrees.”

But, as it stands, designation of either a non-human inventor, or simply no inventor does not satisfy the requirements of Article 81 EPC. It is thus within the rights of the receiving section to refuse such an application. These formal requirements of Article 60(1) and 81 EPC cannot be ignored.

Whilst the Board appeared to take a firm position that formal requirements cannot be ignored, they did however appear to be amenable to a situation where no inventor was named, should none exist, thus disregarding the first sentence of Article 81 EPC. Whilst this may seem contradictory, the logic behind this position was that the purpose of this provision is to confer rights to the inventor, which is not necessary where the inventor does not exist.

Whether this situation is unjust, the Board stated that it is a task for the lawmakers to potentially amend the EPC should a problem exist, and not for the Board to propose a solution to this scenario. Nevertheless, the Board did appear to suggest that the solution is that the owner and creator of the AI system should simply designate themselves as the inventor, see reasons for the decision paragraph 4.6.6:

“The Board is not aware of any case law which would prevent the user or the owner of a device involved in an inventive activity to designate himself as inventor under European patent law.”

Could this be taken as an implicit suggestion that the creator and owner should just designate themselves as the inventor? Even if this approach is the only practical solution, applicants may nevertheless find this to be unsatisfactory. As the use of AI systems becomes more widespread, it seems likely that in a commercial setting the creator, the owner, and the user of the AI may be different people, leaving the rightful owner of the patent unclear. Additionally, the Board’s apparent suggestion may be incompatible with national law. For example, under US law, this could be considered to be a false statement under oath, jeopardising patentability or even risking criminal proceedings.

As the Board state that the ‘user’ could be deemed the inventor, they appear to envision that there must be some degree of human input into an AI generated invention. However, it remains unclear what level of input would be required to make someone the user. Could an action which does not involve inventive skill in of itself, such as inputting a seed value, selecting a preferred outcome, or even just clicking ‘go’, be suitable to impart inventorship onto a user of an AI system?

For now, we will have to await future decisions or changes to the EPC before having any further clarity on AI inventorship before the EPO.

This recent decision by the European Patent Office (EPO) Boards of Appeal (T 2627/17) highlighted the way in which the ‘sufficiency of disclosure’ requirements under Article 83 EPC can lead to different (and perhaps counterintuitive) outcomes for claims to medical uses in general (so called ‘first medical use’ claims) and for claims to specific medical uses (so called ‘second medical use’ claims). In T 2627/17, the Board held that in vitro data in the patent were supportive of the (broader) first medical use claim, but not the (narrower) second medical use claim.

In overview, the patent relates to compounds for use in the treatment or prevention of diseases or conditions that are estrogen sensitive, estrogen receptor dependent, or estrogen receptor mediated (collectively, such compounds are said to have ‘ER activity’). The patent contained in vitro data demonstrating ER activity of a large number of compounds which fall within the scope of the claims in estrogen-dependent breast cancer cell lines. The patent also contained a discussion linking ER activity with estrogen-dependent cancer therapy.

The patent granted with claims directed to compounds per se, use of the compounds in medicine (first medical use), and use of the compounds in the treatment of a wide range of specific conditions including various types of cancer, alcoholism, arthritis, migraines, dementia, and infertility (second medical uses).

First medical use claim

During the appeal proceedings, the appellant argued that the alleged ER activity was not supported across the wide range of compounds covered by the claims.

The Board disagreed, and referred to T 609/02 (Reason 9), which noted that “for demonstrating sufficient disclosure of a therapeutic application, the patent must provide some information in the form of, for example, experimental tests, to the avail that the claimed compound has a direct effect on a metabolic mechanism specifically involved in the disease, this mechanism being either known from the prior art or demonstrated in the patent per se.” (emphasis added).

Demonstration of ER activity, combined with a discussion linking ER activity with estrogen-dependent cancer therapy, was ultimately held to support the (broad) medical use claim.

Second medical use claim

The appellant argued that the ER activity data in the patent were limited to a specific breast cancer cell line, and that these data did not support each of the specific conditions listed in the second medical use claim.

The patentee (respondent) argued that the patent rendered it plausible that ER activity is involved in each of the conditions listed in the second medical use claim, and that each of those conditions were therefore sufficiently disclosed.

The Board decided that the data, combined with the discussion linking ER activity with existing estrogen-dependent cancer therapies, supported treatment of estrogen-dependent cancers.

Regarding the other conditions listed in the second medical use claim, the Board again pointed to T 609/02 (Reason 9) and noted that in vitro data may support a therapeutic application “if there is a clear and accepted established relationship between the shown physiological activities and the disease” (emphasis added). Without evidence of an established relationship between ER activity and the other conditions listed in the second medical use claim, those other conditions were considered insufficiently disclosed.

Outlook

T 2627/17 highlights the considerable importance of establishing a relationship between a biological or a physiological activity and a disease or a condition, particularly when supporting data for that disease or condition are unavailable. Patent applications are often filed before robust in vivo (or even in vitro)data are available, and so investing time at the drafting stage to explain why or how a demonstrated biological activity is relevant to a condition, can pay significant dividends.

T 2627/17 contained a further quirk: even though the second medical use claim was considered ‘bad’ for treatment of conditions other than estrogen-dependent cancer, those other conditions were nevertheless covered by the broader scope of the granted first medical use claim and claims to the compounds per se.

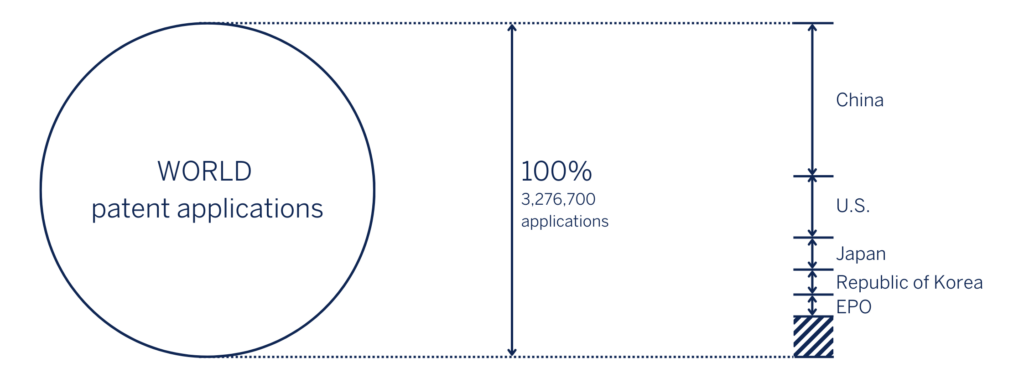

According to the WIPO Statistics Database, in 2020, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) received 1.5 million patent applications, accounting for 45.7% of the world’s total filings (see Fig.1). From a quantity perspective, China has become the top filer of patent applications in the world. However, it is clear that this is merely a stepping stone, with new targets for high-value invention patents being part of the latest five-year plan for the period from 2021 to 2025.

What are high-value invention patents?

The CNIPA considers the following invention types as high-value:

- A patent in the strategic emerging industries;

- A patent with overseas patent family member(s);

- A patent maintained for more than 10 years after grant;

- A patent that realises a higher amount of pledge financing; or

- A patent that wins State Science and Technology Awards or the China Patent Awards.

The 14th five-year plan

China’s five-year plans have been known for their importance to the nation’s economic growth, development, corporate finance, and industrial policies. In the most recent plan (2021 to 2025), China has defined a new indicator as one of the main 20, highlighting the number of high-value invention patents per 10,000 population:

| Category | Indicator | 2020 | 2025 |

| Innovation-driven | 5. Number of high-value invention patents per 10,000 population | 6.3 | 12 |

The number of high-value invention patents is considered to be an objective measure of its innovation performance and its position in global innovation competition. By 2025, it is expected that the number of high-value invention patents per 10,000 people in China will reach 12, which would improve the nation’s innovation performance, hopefully providing powerful support for economic development.

China Patent Awards

Ever since The China Patent Award’s debut in 1989, the award has become the most prestigious and highest award available in the field of patents in China. Winners of the awards are selected in different categories to celebrate innovation across various industries and technologies. Up for grabs are patent awards including 30 Gold Awards, 60 Silver Awards and a number of Excellence Awards, as well as 10 Gold Awards, 15 Silver Awards and numerous Excellence Awards for registered design owners.

According to the CNIPA, during the 13th five-year plan (covering the period of 2016 to 2020), 130 Gold Awards were awarded, and the inventions covered by those awards created sales accounting for more than 1 trillion RMB. Nowadays, the awards are becoming more valuable and competitive, as the winners’ inventions automatically become considered high-value invention patents.

Faster but stricter patent examination in China

On 21 March 2022, the CNIPA also released the ‘Annual Guidelines for Facilitating High-Quality Development of Intellectual Property 2022’. The target for the examination period of an invention patent application has been reduced to 16.5 months, three months less than that for 2021. The target set for an evaluation of a high-value invention patent application has been reduced further to 13.8 months. CNIPA has clearly already taken into consideration its new indicator when examining patents and it is expected for their examination to be more efficient and timelier than that of standard applications.

In practice, however, the reduced examination period may put more pressure on the examiners’ shoulders to make a rushed decision on whether to grant or reject an application. Therefore, the patent applicants may be given fewer opportunities to defend the applications to avoid rejections in the examination process, and instead might have to further pursue the invention in a less ideal re-examination process, with the unintended consequence of reducing patent quality.

With the latest five-year plan underway, businesses in China are already adjusting. The introduction of the new indicator may promote high-value patent filings; however, the new stricter examination process might pose a hurdle to this goal. As per the definition of ‘high-value’ patents, Chinese companies have become keener to build patent portfolios abroad both to establish a foundation for maximising competitiveness as well as eligibility to the ‘high-value’ label. With that in mind, many businesses have resorted to reaching out to patent attorneys, who are able to guarantee the highest chance of ensuring grant of a patent both locally and abroad.

(C) Naomi Korn Associates & Mathys & Squire 2022. Some Rights Reserved. These case studies are licensed for reuse under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike Licence.

The following case study has been taken from the “Implications of Covid-19 on SMEs – reassessing the role of IP in multiple sectors and industries” report written by Naomi Korn Associates and Mathys & Squire Consulting, November 2021. This case study reviews the impact on SMEs (small, medium enterprises) of the COVID-19 pandemic since its appearance in early 2020 through the first quarter of 2021. It focuses on the industries most affected by the crisis and whether intellectual property (IP) and IP management may have helped mitigate its impact through adaptation and change.

Sector overview

The manufacturing sector has been hard hit by COVID-19. A recent report suggested that due to staff furloughs and job losses, customers are likely to curtail spending except for groceries, medicines, and home entertainment. This has a knock-on effect for the manufacturing sector including cars, apparel, textiles, furniture, and appliances as well as the broader business to business industry. Furthermore, the report estimates that across Europe, up to 25% of jobs in the manufacturing sector may be at risk, which equates up to almost eight million jobs across several manufacturing industries. This figure can be multiplied many times over looking at the challenges facing the global manufacturing sector.

Analysis

In the earlier days of the pandemic, there was a global shortage of ventilators, required for treating COVID-19 patients. Similar shortages were observed for PPE, alcohol hand sanitiser and anti-COVID-19 drugs. These challenges resulted in existing producers ramping up production, and many businesses and inventors coming up with innovative solutions and alternative technologies. One technology area that benefited from increased innovation as a result of the pandemic driven demand increase is additive manufacturing and 3D printing. The digital technique allows extreme flexibility in production and easy customisation, meaning that prototypes for new products can be easily generated. As such, this technique has been used to generate specialist parts to help fight the pandemic. Italian company Isinnova produced a 3D printed Charlotte valve capable of connecting to snorkelling equipment, allowing for production of positive air pressure devices from standard snorkelling kit. Likewise, 3D printing has been used to produce mask filters and face shield parts [1]. In this context, German multinational Siemens enabled access to its additive manufacturing network for any parties needing assistance in medical device design and manufacture. Being a partially digital tool, complex 3D printing designs were shared globally online. An obvious issue in this context is infringement of IP rights such as patents, designs or copyright, however, initially it was assumed that good intentions and an ethical approach would prevent potential legal actions or wilful IP theft.

At the beginning of the pandemic, countries across the world experienced severe shortage of hand soap and alcohol sanitisers, caused by a boom in consumer demand and the supply chain unable to cope with it. In the case of PPE, this shortage was caused by panicked bulk buying of unsuitable equipment. Many manufacturing facilities were faced with a level of demand they were not designed for and never intended to deliver for, however it has been noted that many operational changes occurring in manufacturing due to COVID-19 were already underway and the arrival of the pandemic has simply accelerated these processes. This challenge has had several interesting consequences, many of which have impacts on IP rights moving forward.

In the case of ventilators, numerous governments and regulators, temporarily reduced requirements to enable non-medical industry manufacturers to produce ventilators and promoted production under forced collaborative manufacturing arrangements. In the UK, the VentilatorChallengeUK Consortium, comprising businesses across multiple industries was established to meet the increasing and urgent demand for ventilators. The UK government indemnified participants from accidental infringement of IP rights, competition and procurement law and aspects of product failure. Consortium designers and manufacturers were offered an IP indemnity by the UK Government, thus allowing the various partners to push forward with the task of producing ventilators without worrying about potential infringement. While the level of indemnity was not released, it was believed that the government undertook a contingent liability in excess of £3m, which gave consortium members confidence to partner with other firms.

Several governments, such as Chile or Canada, have also gone as far as issuing compulsory licences to produce PPE or ventilators, as well as anti-COVID-19 medication, such as Kaletra in Israel [2]. These compulsory licences have been issued with the caveat that the product being produced is free of charge for emergency use only and future commercial production would require the appropriate licence agreement [3]. The demand for PPE and hand sanitiser has also caused a number of manufacturers to modify their business models, including moving towards ecommerce and teleworking environments, as well as modifying their supply chain and using existing facilities to produce new products to meet demand. Going digital has not simply meant a move to online sales, but the development of a robust digital plan, which offered many SMEs the chance to streamline and automate many aspects of their business, resulting in improving efficiency and reducing costs. This digitalisation, along with new working patterns and shaking up of existing supply chains will create many new offerings for SMEs, especially those who have also carefully managed their cash flows during this period.

In addition to changes in business models, many businesses have also pivoted towards completely new goods and services offerings. Textile manufacturers such as Zara or Prada have produced face masks, while perfume manufacturer LVMH has used their facilities to make hand sanitisers. Many of these expansions into new markets by established companies have been successful in their new activities by growing their existing brand recognition and trade mark portfolios.

Some companies have sought to assist during the pandemic through a more direct use of their IP. The Open Covid Pledge providing a patent pool offering use of COVID-19 related patents is a good example. Under the pledge, companies with patents covering COVID-19 related inventions offered the open COVID-19 standard or open COVID-19 compatible licences to external businesses. The licences are offered royalty free for use by their owners for the duration of the pandemic until one year after its official end, as declared by the World Health Organization.

However, for companies producing crisis critical innovations such as PPE, sanitising gel and medications, the boom in demand has caused an increase in passing off and counterfeiting. In March 2020, a joint international police operation (Operation Pangea XIII) made 121 arrests and confiscated over 34,000 counterfeit surgical masks, ‘corona spray’, coronavirus packages and counterfeit medicines [4]. Similarly, in May 2020, the Italian Guardia di Finanza seized 900 counterfeit children’s masks [5]. With the innovation and licensing programs seeking to exploit all available technologies in the fight against COVID-19, innovative companies may find their IP being infringed, their products being copied, as well as a loss of enforceability of IP where compulsory licences have been granted. These companies will need to ensure that they do not miss out on potential commercial opportunities, but also that they remain sympathetic to the harsh economic and health circumstances, whilst understanding the potential reputational damage suing an infringing party during the pandemic might cause. For example, the non-practicing Labrador diagnostics sued the practicing company Biofire for alleged infringement of two of its patents. However, this misfire from Labrador has caused reputational damage and it delayed the development of potentially useful critical crisis technologies. Labrador diagnostics has since announced a royalty free licence to anyone developing COVID-19 tests, as well as extending the deadline for potential infringing parties to come forward. In another more positive example, truck manufacturer Scania provided some of its manufacturing experts to Swedish company Getinge to enable them to ramp up their ventilator production. In doing so, the company clearly improved the production capacity of Getinge, and thus the fight against COVID-19, without risking the core technology IP of Scania.

The European Commission is also putting in place an action plan to help SMEs impacted by COVID-19 by introducing new licensing tools and a system to co-ordinate compulsory licences [6]. In addition to this, the Commission is aiming to simplify the sharing of information and introduce mechanisms for quick pooling of patents, in order to efficiently meet the needs of those fighting COVID-19. Action points include backing of the Unitary Patent system, optimisation of the use of supplementary protection certifications, as well as the revision of EU legislation surrounding designs and plant variety protection. Furthermore, to directly assist EU based SMEs, IP vouchers will be available for one year to help such businesses manage their IP portfolio. Importantly, the Commission will also investigate methods of support for IP backed financing and seek to support SMEs in this context, in a similar manner to the Japanese government’s support on IP securitisation.

In the context of the current pandemic, when a company believes it is infringing someone else’s IP right, it should contact the relevant IP owners with the aim of securing a licence (potentially royalty free for the duration of the pandemic). Alternatively, companies may decide to drop enforcement of specific patents for the duration of the pandemic, similarly to AbbVie not enforcing Kaletra patents. However, companies failing to be flexible with their IP enforcement and licensing policy during the pandemic may find their products being reverse engineered and alternative, non-infringing products, being developed, thereby causing both reputational damage and loss of market share.

[1]Choong, et al (2020): The global rise of 3D printing during the COVID-19 pandemic, Nature Reviews Materials

[2] Tietze, Frank et al. (2020): Crisis-Critical Intellectual Property: Findings from the Covid-19 Pandemic, University of Cambridge

[3] Baker McKenzie (2020): COVID-19: A Global Review of, Baker McKenzie

[4] International Chamber of Commerce (2020): Disruptions caused by Covid-19 increase the risk of your business encountering illicit trade risks, ICC

[5] Verducci Galletti, S (2020): Challenging times: anti-counterfeiting in the age of covid-19, WTR

[6] European Commission (2020): Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions- Making the most of the EU’s innovative potential, European Commission

Naomi Korn Associates is one of the UK’s specialists in copyright, data protection and licensing support services.

Mathys & Squire Consulting is an intellectual property consulting team that can support all businesses in capitalising intangible assets.

Naomi Korn Associates and Mathys & Squire Consulting are working in partnership across multiple industries to provide innovative consultancy IP support services.