The number of blockchain patent filings has exploded in recent years at almost every patent office, but as of yet there have been very few decisions on the patentability of blockchain above the level of patent examiners. Patentability has mostly been decided by individual examiners following the guidance for more general computer-implemented inventions – and this has led to a degree of inconsistency between patent offices (though of course this occurs with many types of invention) and between examiners at individual offices.

Fortunately, a recent decision of the Australian Patent Office: Advanced New Technologies Co., Ltd. [2021] APO 29 (21 July 2021) casts some light on the patentability of blockchain in Australia and offers guidance that might be followed by other patent offices.

In short – at least in Australia – it seems as though blockchain is by and large patentable subject matter.

The decision relates to the patent application AU2018243625, an application filed by Advanced New Technologies Co., Ltd with a filing date of 21 March 2018 and a priority date of 28 March 2017.

Chronologically:

- A first examination report issued on 23 January 2020 asserted that all the claims were directed to unpatentable subject matter and lacked an inventive step.

- Following some back and forth, the applicant managed to convince the examiner that the claims were inventive, but in a fourth examination report issued on 7 January 2021, the examiner maintained the position that the claims were directed towards unpatentable subject matter (the examiner also introduced a new objection that the specification did not provide a clear and complete disclosure of the claimed invention).

- The applicant responded on 22 January 2021 requesting to be heard in relation to the outstanding objections and filed submissions explaining why these outstanding objections should be withdrawn.

Turning then to the substance of the application, the application states that: “there is a need to solve the technical problem of how to design a method for verifying a transaction request, such that there is no risk for privacy breach of a blockchain node participating in the transaction”.

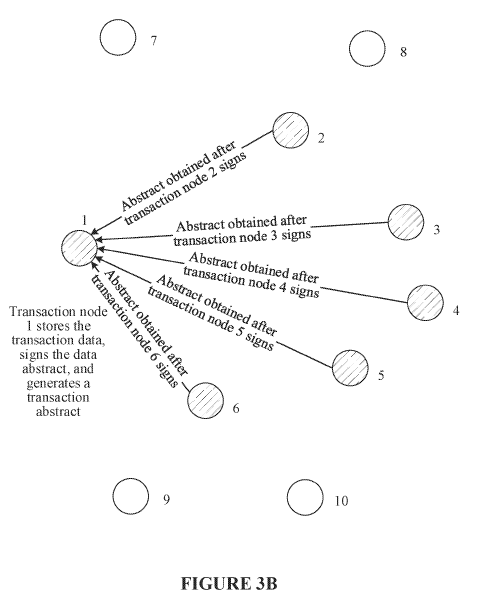

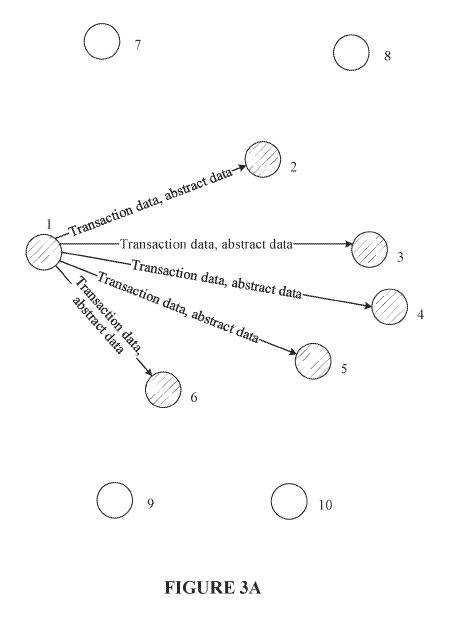

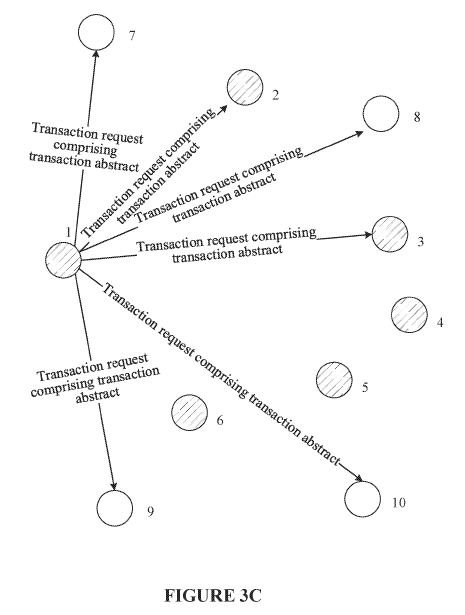

The invention proposed to solve this problem is illustrated by figures 3A – 3C of the application, which are reproduced below:

The claim 1 proposed by the applicant’s submissions is rather long, and therefore is not copied here in full, but essentially the claim relates to the generation and broadcasting of a transaction request in order to “caus[e] the consensus nodes to each save the transaction abstract in the transaction request into a blockchain after the transaction abstract passes the consensus verification”.

The examiner was of the opinion that the invention “concerns the mere implementation of an abstract idea in an unspecified manner within a particular computer/computing environment”.

More specifically, the examiner argued that: “it becomes apparent that the substance of the invention lies in the abstract idea of not sending particular information as part of the transaction processing. Moreover, it is evident from the specification that the substance of the invention lies solely in the content of the data rather than any technical intervention on the part of the inventors.”

Turning then to the decision, the delegate of the commissioner did not agree with this view of the examiner. The standout statement made by the delegate is the statement that: “I can see no reason why technical improvements to fundamental mechanisms related to consensus within a blockchain should not be patentable, even though these improvements might not necessarily be addressing technical problems. In my view, the balance of considerations weigh in favour of finding that the claimed invention is a manner of manufacture.”

This is of course good news for patent practitioners looking to patent blockchain technologies and confirms the patentability of even core blockchain inventions (at least in Australia).

It is worth mentioning that this view (i.e. that blockchain inventions are technical and patentable) is not unusual. Most patent offices are amenable to blockchain inventions to some extent at least, though it is notable that the UK Patent Office tends to view blockchain inventions unfavourably (with only a small number of blockchain patents having made it through to grant in the UK). It is however encouraging to receive such a positive decision from a higher authority than an examiner.

Turning back to the decision, the delegate later stated: “However, I have serious concerns about the inventiveness of the claimed invention. I therefore refer the application back to examination in order to reassess the inventiveness of the claimed invention ….” – so while blockchain inventions seem to contain patentable subject matter, they do still need to be inventive! If anything, the fact that the invention was seen as not at all inventive but was still viewed as patentable subject matter should be viewed as very encouraging.

A conclusion that might be drawn from this decision is that for companies seeking blockchain patents, filing an application in Australia is a good idea. Additionally, examiners at many of the Asian patent offices (e.g. Indonesia and Malaysia, etc.) tend to concur with the decisions of examiners of the Australian Patent Office so this decision could be seen as a positive indication of blockchain patentability across much of Asia. When considering previous decisions by patent offices in Europe and the US, western patent offices are less likely to follow the Australian Patent Office so this decision is of less direct relevance, but is of course still an encouraging sign.

In summary, this decision seems to indicate the Australian Patent Office is amenable to blockchain patents – this is not a surprise, but rather is an affirmation of current practices from a significant patent office.