Colin the Caterpillar is a familiar face in many offices, appearing at birthdays and office celebrations since he first hit the shelves in 1990. In recent years, he has also become well known in the world of intellectual property following Marks and Spencer’s trade mark dispute with Aldi over their look-alike product in 2021-22.

On 28 January 2026, Marks and Spencer released a gluten-free version of Colin the Caterpillar in their Made Without Wheat range. M&S joins other major brands that have released gluten-free versions of popular items, such as Arnott’s gluten-free Tim Tams, General Mills’ gluten-free Old El Paso tortillas, and an expanding range of gluten-free Oreos from Mondelēz, reflecting a growing demand for ‘free-from’ alternatives.

This increased demand is being driven in large part by growing awareness of gluten intolerances and coeliac disease. Coeliac disease is an autoimmune disease affecting around 1% of the population. It causes the body’s immune system to react to gluten, a protein found in various grains including wheat, oats, barley and rye. This reaction damages the lining of the gut and can result in symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and abdominal cramping.

The introduction of free-from alternatives requires the development of new food production methods, recipes and even ingredients, both to replace gluten and to ensure the product is still appealing in taste and texture. This raises the question as to whether food manufacturing companies and household brands can obtain protection for innovation in ‘free-from’ food.

Patenting gluten-free innovation

It is a common misconception that recipes and food formulations cannot be patented. As long as an invention meets the criteria of novelty, inventive step and industrial application, patent protection is possible. The novelty requirement means that the claimed invention must not have been disclosed to the public before the filing date of the application, for example through selling, marketing or public display. In the food industry, inventive step, i.e. providing a non-obvious solution to a technical problem, could be satisfied by a product which has an improved taste or texture despite the avoidance of certain ingredients, a synergistic effect arising from a particular combination of ingredients, unexpected health benefits, or a non-obvious substitution for a commonly used ingredient. Having data to support these effects, whether it be from taste tests or mechanical testing, can be crucial to successfully obtaining patent protection. The requirement of industrial application is generally met inherently by products and processes within the food industry. Patent protection for ‘free-from’ alternatives is common, as inventive solutions are required to ensure the products adhere to the standards of traditional food products without an essential ingredient.

Many hundreds of patent applications relating to gluten-free products have been published, as well as many more for other free-from products. Mondelēz, for example, have several pending patent applications for baked goods (EP4188098A1), aimed at overcoming the dense, crumbly, and sandy or granular texture, poor mouth feel, inferior appearance, and relatively short shelf life it claims are usually associated with gluten-free goods. General Mills have been granted a European patent [A2] [A3] directed to gluten-free tortillas comprising a novel mixture of gluten-free flours (EP3468371B1), with good toughness extensibility and rollability. General Mills have also obtained patent protection for a dough comprising a gel matrix (EP3310177B1) which imparts mouth-feel, viscosity and elasticity properties similar to that of a gluten containing composition.

In addition to composition-based claims, patent protection may also be obtained for inventive processes of manufacture. Several patents exist for methods of producing gluten-free doughs and beers by fermenting the grains with bacteria or yeasts that break down the gluten to acceptable levels.

Patenting treatment for Coeliac disease

Currently, those with coeliac disease must maintain a strict gluten-free diet to avoid triggering the symptoms. However, the risk of cross-contamination during manufacture and food preparation can make this difficult in practice. As a result, many organisations are researching methods of treatment which aim to reduce symptoms or decrease a patient’s sensitivity to gluten, with a number of different treatments currently undergoing clinical trials.

Under the European Patent Convention, methods for treatment of the human or animal body by therapy are excluded from patentability. However, this exclusion does not extend to pharmaceutical products and compositions. Therefore, at the European Patent Office (EPO) pharmaceutical companies typically seek patent protection for drug compounds, formulations, dosage regimens and for specific medical uses rather than the method of treatment itself. Formulating patent claims appropriately therefore plays an important role in obtaining patent protection in these situations.

The timing of patent filing for inventions which will need to go through clinical trials also presents a strategic balancing act. Applicants must file early enough to avoid novelty-destroying disclosures arising from academic publications or the registration of the trials themselves, while also ensuring that sufficient experimental data is available to render the claimed therapeutic effect credible at the filing date. Due to the complexity of these considerations, it is advisable to communicate with your patent attorney who can guide you down the optimal path.

Formulations aiming to treat coeliac disease that are currently undergoing clinical trials fall into several categories. These include:

- Enzyme-based formulations which break down gluten before it can trigger an immune response. An example of this is Latiglutenase, a mixture of two gluten-specific enzymes that break gluten proteins into smaller fragments which do not trigger an immune response. While each of the enzymes had been suggested for use on their own to treat coeliac before, the combination of the two was patentable since it was novel and produced an unexpected technical effect, namely the complete detoxification of gluten.

- Monoclonal antibodies which target specific molecules involved in the immune response and reduce the effect. Ordesekimab and TEV-53408 are two such antibodies undergoing Phase II clinical trials. They both work by targeting the protein Interleukin-15, which is involved in the proliferation of T cells that attack the gut during a gluten response. At the EPO, patent protection can be obtained for antibodies that target antigens which have already been targeted but only where an unexpected technical effect can be demonstrated over the antibodies in the prior art. Such effects can be e.g. surprising improvements in therapeutic activity, stability or immunogenicity, or an unexpected property not exhibited by prior-art antibodies.

- Small molecule-based therapies, such as Ritlecitinib, developed by Pfizer and currently used in the treatment of alopecia. Ritlecitinib is an inhibitor of Janus kinase 3 (JAK3) and TEC-family kinases and therefore modulates immune signalling pathways activated by autoimmune responses. This drug is protected by multiple patents and patent applications relating to the compound itself and its use, as well as to its tosylate salt and its crystalline forms. Filing multiple applications in this way allows protection for subsequent developments and optimisations that are made to an original invention (e.g. the discovery of a useful small molecule), and can be useful for extending the length of protection.

These are just a few of the many treatments being researched. Due to the lengthy authorisation process for medicinal products, much of a patent’s lifetime may be used up before the product can even enter the market. To somewhat mitigate this loss of effective patent term, proprietors of medicinal product patents can apply for Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) in the UK and in each of the EU member states, as well as certain other non-EU European countries. SPCs can extend the term of protection granted by a medicinal product patent up to a further 5 years after expiry of the relevant patent. A further six-month extension may be acquired where certain studies have been performed looking into use of the product for the paediatric population. For further information see our page on Supplementary Protection Certificates here.

The treatment of coeliac disease is a growing field of research, with many hundreds of patent applications published each year in this area. Until such therapies receive regulatory approval, those with coeliac disease will continue to rely on a gluten-free diet, but hopefully, through utilising the advantages of good IP protection, a less dense, crumbly and sandy future is on the horizon.

Click here to read more about our IP expertise in the food industry.

The European Patent Office has released a preview of the amended Guidelines for Examination, which are due to enter into force on the 1st of April 2026.

The amendments incorporate a variety of updates including the addition of information that was previously contained in the Euro-PCT Guide (Part A), the processing of colour drawings (Parts A, C, and H), additional information relating to the use of artificial intelligence (AI) at the EPO (General Part and Part E), the abolition of accelerated search under the PACE program (Part E), a new chapter on the sufficiency of disclosure of further medical use claims (Part F), and reflection on the Board of Appeal decisions G 1/23 and G 1/24 (Parts G and F).

This article will focus on a selection of these updates.

AI Use at the EPO

The use of AI tools is addressed in three places in the updated Guidelines. The first is in the new General Part Section 5, where the EPO’s stance that the parties are responsible for the content of patent applications, regardless of whether a document has been prepared with the assistance of AI, is reinforced. This statement reflects the generative AI guidelines issued by the epi in 2024. The second addition to General Part, Part 5, is the notice that the EPO may use AI to improve the quality and efficiency of its work.

The final addition (E-III, 10.1) relates to the use of AI tools for the creation of meeting minutes of oral proceedings held by video conference before the examining and opposition divisions. The addition states that sound recordings will be made when minutes of oral proceedings are made with the assistance of AI, but that these recordings will not be issued to the parties and will be deleted after the distribution of the minutes.

One well-recognised weakness of AI is its tendency to hallucinate (produce responses that are presented as fact but contain fabricated or incorrect information). Therefore, any outputs generated by AI tools should be thoroughly reviewed to ensure their accuracy before being submitted to official offices. Likewise, any communications from the EPO should be carefully reviewed as AI may have been used to prepare them. Additionally, AI is often unable to correctly summarise complex legal topics, and as such any EPO minutes generated using AI tools should be carefully reviewed by the parties for accuracy. Parties should also continue to make their own detailed notes and minutes from proceedings so that they can be compared with the official EPO minutes.

Colour drawings now permitted

Updates throughout Part A confirm the 5th of September 2025 notice that the electronic filing of colour and greyscale drawings is permitted, including for European divisional applications. Drawings in colour or greyscale filed electronically on or after the 1st of October 2025 will now be published in that format. However, late filed missing drawings, any drawings in translations and drawings filed to remedy deficiencies notified by the Receiving Section must adhere to the format of the original drawings, i.e. they may contain colour or greyscale content only to the same extent as the original drawings.

These additions are a positive change, providing improved flexibility for applicants and ensuring drawings are represented more accurately.

Claim interpretation

In response to G 1/24, which deals with claim interpretation, the EPO has updated the guidance in F-IV, 4.2 relating to interpretation.

The guidelines now state that whilst the claims are the starting point and the basis for assessing the patentability of an invention, the description and drawings are always referred to when interpreting the claims, and not only when there is a lack of clarity or ambiguity. However, the description and drawings cannot be relied upon to bring a restrictive feature into the claim that is not suggested by the wording of the claim. If, conversely, the description provides a special broad definition of a term used in a claim, the claim must be interpreted in light of that broad definition, provided the interpretation is technically meaningful.

These updates align EPO practice with the practice of the UPC and national courts, marking the departure from the previous “claims only” approach. This means that applicants must ensure that the language in the description aligns with the claims, as wording in the description could directly affect claim scope. Additionally, applicants may be in a stronger position to challenge examination objections based on an overly narrow interpretation of the claims.

Products on the Market: G 1/23

In light of G 1/23, relating to products on the market, the guidelines surrounding prior art and enabling disclosure (G-IV 2 and G-IV, 7.2.1) have been amended.

They now state that a product put on the market before the date of filing an application, and all its analysable parts, form a part of the state of the art. The requirement of reproducibility is inherently fulfilled by the fact that the skilled person is able to obtain and possess the product. Technical information about such a product, such as technical brochures and non-patent and patent literature also forms a part of the state of the art, irrespective of whether the skilled person could analyse and reproduce the product.

These updates make it increasingly important for applicants to file patent applications before making any public disclosures, particularly when releasing a product on the market or publishing technical materials.

The full preview of the amended Guidelines for Examination is available on the EPO website.

The Supreme Court has this morning issued a press release announcing its decision in the case of ‘Emotional Perception AI Limited (Appellant) v Comptroller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (Respondent)’. A copy of the judgement can be found here.

In brief, the Supreme Court has allowed the appeal and decided:

- UK courts should no longer follow the four-step test set out in Aerotel Ltd. v Telco Holdings Ltd & Ors Rev 1 [2006] EWCA Civ 1371 (often referred to as the ‘Aerotel test’) for assessing whether an invention, particularly for software and business methods, is excluded from patentability.

- UK courts should, instead, follow the ‘any hardware’ approach endorsed by the Enlarged Boards of Appeal of the European Patent Office (EPO) (decision G 1/19), whereby any hardware element in a claim will convey technical character and avoid the exclusions.

- UK Courts should also follow the EPO’s approach to assessing claims directed to a mixture of technical and non-technical subject matter endorsed by G 1/19; that is, once the “very low hurdle” of satisfying the any hardware approach is met, the next ‘intermediate’ step is to filter out features that do not contribute to the technical character of the invention, viewed as a whole, from subsequent consideration during assessment of inventive step.

- The Court of Appeal’s description of a computer as “a machine which processes information” is too broad, but in light of changing technologies no strict definition is appropriate.

- A program for a computer is “a set of instructions capable of being followed by a computer (of any kind) – which may or may not have a CPU – to produce desired manipulations of data”.

- An artificial neural network (ANN), regardless of how it is implemented, is not itself ‘computer’. However, applying the ‘any hardware’ approach to this case, although the claims of the patent application involve an ANN, they involve technical means and are therefore not excluded for being a computer program as such.

The UK Supreme Court’s adoption of the EPO’s any hardware approach and intermediate step of filtering out non-technical features moves UK and EPO practice closer together. Concerns were raised by the Comptroller that these changes would interfere with the UK’s long-settled approach to assessing inventive step as set out in Pozzoli v BDMO SA [2007] EWCA Civ 588 (often referred to as the ‘Pozzoli test’), in effect requiring the UK to also adopt the EPO’s ‘problem-solution’ approach to assessing obviousness. However, the Supreme Court dismissed these concerns, holding that the problem-solution approach is not the only way of assessing inventive step and that the Pozzoli test “remains a legitimate approach”.

In practice, since almost all software inventions are computer-implemented, the ‘any hardware’ test can be easily met and the assessment of technical character now becomes part of the assessment of inventive step rather than excluded subject matter; UK applications that may have struggled at the excluded subject matter stage might still struggle at the inventive step stage. How in practice the newly adopted ‘intermediate step’ is applied (e.g. how technical character is assessed and how old case law applies) and impacts assessment of obviousness at the UKIPO remains to be seen.

This week, from the 9th to the 15th February, marks National Apprenticeship Week, an initiative led by the UK Government to celebrate the vital role apprenticeships play in developing individuals, strengthening businesses, and supporting wider society.

At Mathys & Squire, we are proud to offer IP Support apprenticeships that nurture enthusiastic, motivated talent and provide hands-on training in the world of intellectual property. Our apprenticeships create clear and accessible pathways into skilled employment, particularly for young people and career-changers who may not follow traditional academic routes.

In this article, we hear directly from our talented apprentices as they share their experiences and reflect on their journey at Mathys & Squire so far.

Victoria Perryman

Victoria Perryman began her apprenticeship in August 2024 and has just sat her final exams.

“Being an apprentice at Mathys & Squire allowed me to begin my career within the IP industry and have hands-on experience with completing day-to-day activities of Intellectual Property Support Specialists, while balancing off-site learning and study required by the Apprenticeship Board. This has helped develop my understanding of the working world, create networks with a range of people, as well as build my personal and academic confidence. My apprenticeship at Mathys has given me so many opportunities and responsibilities which allowed me to enhance and gain valuable skills.

The apprenticeship has been a challenge, especially with trying to balance working, personal and educational life, however, it has been an enriching and rewarding journey from start to finish. Upon reflection of my apprenticeship journey, I can see how this experience and the people I have worked alongside have supported a positive change in myself, enabling me to build up stronger communication and social abilities.

I have learnt the importance of IP in the everyday working world and how many people lack an understanding of the expansive work involved. My newfound knowledge gained about IP has allowed me to view the general world in a different way and appreciate the effort that IP firms, such as Mathys, goes through to enable other businesses to protect their IP works.”

Alexviya Leigh

Alexviya and Tilly-Grace both began at Mathys & Squire in August 2025.

“Joining Mathys as an Apprentice has been a very exciting and rewarding experience. From the very first day, I was welcomed into a supportive environment where collaboration and learning are encouraged. Unlike some roles where Apprentices are limited to observation, I was given responsibilities and the chance to contribute to real work, which has made me feel like a valued part of the team. Balancing work with study has been a little challenging but enriching. I have been able to develop strong organisational skills, learn how to manage multiple deadlines and apply what I have learned from my coursework into a practical setting.

Overall being an apprentice at Mathys & Squire has given me a unique insight into the legal profession and is a solid foundation for my career. The role is challenging, fast-paced, and continuously rewarding, offering both practical experience and academic development. It has confirmed my passion for intellectual property law and provided me with the skills, confidence and perspective to succeed in the field.”

Tilly-Grace Dorking

“For me, starting my professional career with an apprenticeship at Mathys & Squire has been challenging but extremely rewarding and interesting.

I challenge anyone who dismisses apprenticeships as a lesser form of education to spend a day as a Trainee in our firm… I learn something new every day!

One thing I have learnt during my time here is the significance of my role and my department as an Intellectual Property Support Specialist.

Through the training of those in admin/secretarial roles in patents, I have gained insight into how our Attorneys work closely with Intellectual Property Support Specialists and how this fosters a collaborative working environment.”

We are are delighted to announce that Partner Claire Breheny has been mentioned in the 2026 Stand-Out Lawyers List by Thomson Reuters.

Thomson Reuters provides industry-leading insights and trusted expertise for professionals to reinvent the way they work. The list of Stand-Out Lawyers is compiled using a detailed analysis of client nominations from the last four years, narrowing down a large selection of candidates to the lawyers which display exceptional talent.

The life sciences is a rapidly growing sector, tackling issues which closely impact humans. Advances in technology, particularly in the digital sphere, met with an evolving regulatory landscape are reshaping the industry, especially across medical treatments and drug discovery. AI and cutting-edge computer models are accelerating R&D, whilst the EU Pharma Package, agreed in December, marks the first time in over twenty years that there has been a major overhaul of the EU’s pharmaceutical rules.

As technology develops, the number of patent filings are growing in tandem. Crowded patent landscapes mean that a robust intellectual property strategy is key and there may be a shift in the way companies approach their IP in response to the rise in competition. Strong IP protection is particularly essential for life sciences companies. As the process of developing a product is so lengthy, owning IP adds value to a business before there is a concrete product or a source of revenue.

In this article, Associate Max Ziemann unpacks the innovation in medicine and pharmaceuticals which has been gathering momentum in the last few years and will shape the sector in 2026.

The UK Life Sciences sector

The UK life sciences sector has a solid history of world-class research, but to ensure commercial success alongside global competitors, the legal and policy landscape is just as integral as the science itself. As the sector undergoes transformation, the UK government must continue to encourage global investment and innovation.

The Life Sciences Sector Plan, published in July last year, shows the government’s commitment to making the UK a leader in life sciences. The plan covers action points such as building an advanced national health data platform and ensuring the MHRA streamlines regulation and market access.

The UK already has a robust IP regime with specialist IP courts, experienced judges and well-established case law. Looking forward to 2026 and beyond, expedited patent examination and patent term extensions may be the next step to fostering innovation.

Areas to watch

Advanced therapeutics

Innovative medical treatments addressing the root causes of diseases which involve the insertion of biological material into the body, such as cell therapy, or the modification of biological material in the body, such as gene editing, have made major leaps in recent years. This new approach to healthcare represents a clear shift towards personalised medicine, where treatment can be designed with each individual patient in mind. It is bringing us closer to curing some of mankind’s most devastating diseases.

For example, CAR-T therapy has already been successful in curing some forms of leukaemia and scientists are continuing to test its potential. Early clinical data suggests that CAR-T therapies could tackle solid tumours, which are notoriously difficult to treat due to their complex mix of cell types, and scientists are also looking beyond cancer into autoimmune disease. In October 2025, a patient in the UK with multiple sclerosis was the first to trial CAR-T therapy.

Evidently, cell therapy is showing no sign of slowing down, remaining a strong area of interest for investment, and we are likely to see many life-changing breakthroughs in the future. As pharmaceutical companies attempt to bring cell therapies into the mainstream, emerging methods, such as allogeneic as opposed to autologous therapies, may gain traction.

Multi-omics

Multi-omics signify another new frontier of precision medicine. Multi-omic data refers to the combination of information from genomics, epigenomics, proteomics, transcriptomics and metabolomics. The integration of this data can be harnessed to classify diseases, identify biomarkers and discover new drug targets.

Progress in computational models is enabling the rapid evolution and uptake of multi-omics. AI, for example, can efficiently mine huge sets of multi-omic data to identify novel drug targets. This will provide researchers with valuable insights into individual disease biology, informing future development of treatments.

Integration of AI into pharmaceuticals

Multi-omics is not the only area where AI can assist: the use of AI across biopharma R&D is not just a possibility anymore, but a core step. The ability of AI to scour vast databases, extract patterns and carry out predictive modelling is revolutionary in speeding up the drug discovery pipeline. AI can be harnessed at almost every stage from target identification to preclinical assessment.

At the start of this year, UK Basecamp Research shared their collaboration with Nvidia. AI models analysed their dataset of evolutionary information from more than a million designed potential new therapies. This resulted in the first demonstration of AI-designed enzymes that can perform precise large gene insertion in humans.

More and more, pharmaceutical companies are strengthening their AI capabilities through acquisitions and strategic partnerships. It is likely that we have only seen the tip of the iceberg of what AI can do when it comes to healthcare.

You can read our previous article on AI innovation in drug discovery here to learn more about how the integration of AI in pharmaceuticals means that, firstly, companies must consider their IP strategy and, secondly, the broader IP infrastructure must take the use of AI into account.

GLP-1

GLP-1-focused obesity biotechs constitute a huge market, estimated to generate more than $150bn in annual revenue by the early 2030s, and investment remained high in 2025.

Competition between leaders in the industry has already kicked off again in 2026. Novo Nordisk launched Wegovy in tablet form at the start of the year, marking a remarkable step for GLP-1 drugs. Originally self-administered with a weekly injection which had to be stored in the fridge, the oral alternative could make the drug more accessible for a larger group of people.

Keeping apace, Nimbus Therapeutics also announced that they have entered into a long-term licensing agreement with Eli Lilly. This partnership is driven by the goal of developing new oral treatments, as Novo Nordisk has done. They are also planning to use AI to help identify drug candidates, another example of AI’s new key role in drug development.

In addition, GLP-1RA is now attracting attention for purposes beyond tackling metabolic diseases. Clinical trials have shown that cardiometabolic and anti-obesity drugs could even slow down the process of ageing. Other trials are exploring the efficacy of GLP-1RA in specific diseases associated with old age, such as Alzheimer’s. Over the next few years, we may start to see the first wave of ‘longevity’ therapeutics: medication to increase both health span and lifespan.

3D bioprinting

Bioprinting is an exciting new application of 3D printing: the 3D printing of cellular structures from living cells. Its success unlocks many opportunities, such as the creation of tissue-like constructs for grants or scaffolds, modelling of human organs or 3D tumour models, and, beyond medicine, its use is being explored for novel food structures, such as in the alternative proteins sphere.

In March last year, scientists from Newcastle University unveiled a new 3D bio-printer that produces human-like tissue. This has the potential to revolutionise drug development, providing a more accurate alternative to testing on in-vitro cell cultures.

The possibility of printing cells which could actually be inserted into the human body is also being investigated. For example, scientists have printed insulin-producing human pancreas cells, bringing us closer to an off-the-shelf treatment for diabetes that could one day eliminate the need for insulin injections.

An IP perspective

Emerging trends in pharmaceuticals, and in particular New Chemical Entities, will inevitably require a robust IP strategy to be fully commercialised.

Even where developments do not relate to New Chemical Entities, various patent strategies exist to prolong the protection of pharmaceuticals. Second generation patents can be used to cover new medical indications, dosage regimens, methods of synthesis, innovative formulations, combination therapies, treatments of specific symptoms or sub-populations, etc. These tools are of great importance in the pharmaceutical industry, in particular where a large proportion of the original patent lifespan may have elapsed prior to market authorisation of the pharmaceutical.

The integration of AI systems into drug discovery presents a new question of the inventiveness of any intellectual property that arises. Inventions made with the assistance of artificial AI are increasingly facing objections on the grounds of obviousness/lack of inventive step. This means that Patent Offices may be increasingly taking the view that the bar for inventiveness has been raised and is not met by ‘routine’ use of AI systems. A change in policy from Patent Offices worldwide could reduce the value IP generating AI systems if such breakthroughs are no longer seen as suitably ‘inventive’.

The integration of AI systems into drug discovery also presents a new question of inventorship of any intellectual property that arises. The established case law at the UKIPO and the EPO is currently that AI system may not be named as an inventor on a patent (read more here). This means that the default position is that the person using the AI system is the inventor, from whom ownership rights are derived. However, AI companies are increasingly looking towards ‘performance based licencing’ models which could see them share in the financial success of new IP that was developed using their AI systems.

It seems that an AI system capable of producing this type of innovation may in of itself hold a far greater commercial value than the innovations it produces. This means that this system would also require an IP protection strategy. Increasingly, AI systems themselves as well as multi-omics-based approaches may face a trade-off between whether optimal protection is provided by patents and trade secrets. Patents directed towards these kinds of systems are typically not allowable in the UK or Europe, although methods exist for Applicants to avoid these restrictions. Trade secrets on the other hand may last indefinitely and do not run the risk of being denied by Patent Offices, but it is not clear how much value this would hold in such a fast-moving sector. For this reason it seems likely that a combination approach would be the optimum strategy for many innovators.

Emerging trends in life sciences, particularly in the way that research takes place, are fundamentally changing the way that IP protection is used. Value may be shifting from isolated molecules toward platforms, data, methods of use, and integrated digital systems, requiring more combined IP protection strategies.

Partner Nicholas Fox has been featured in ‘UK patent grants drop by 80% as digital upgrade hits processes’ in MLex.

The article explores the sharp decline in UK patent grants following the UK Intellectual Property Office’s rollout of its “One IPO” digital upgrade, which has temporarily disrupted patent granting. Data shows domestic patent grants fell by around 80% in the second half of 2025 as the new system was implemented.

Nicholas Fox commented that the drop is unlikely to significantly affect most UK businesses, as the majority of patents in force in the UK are granted via the European Patent Office, making the reduction in UK domestic grants relatively insignificant.

Read the article in full here.

We are happy to announce that Mathys & Squire is sponsoring the “Hard Tech Investment of the Year” award at the 2026 UKBAA Angel Investment Awards for the second year running. Mathys & Squire will also be part of the judging panel for this year’s nominations which span across 14 categories.

The UK Business Angels Association (UKBAA) is the national trade association for angel and early-stage investment, fostering a tight-knit community of investors. Their annual Angel Investment Awards, taking place on the 9th of July this year, celebrates the role of angel investors, crowd funders and early-stage VCs in driving innovation across the UK, as well as showcasing the businesses they support.

The “Hard Tech Investment of the Year” award showcases those pioneering in sectors such as health & life sciences, engineering and manufacturing, which require extensive R&D and capital. At Mathys & Squire, we are committed to supporting these purpose-led businesses and early-stage investors which are stretching the boundaries of technology.

Nominate someone you admire through their website here. Applications close on the 10th of April.

Find out more about the event and award nominations here.

You can learn more about the partnership between our Scaleup Quarter and the UKBAA here.

World Cancer Day, held each year on 4 February, highlights both the continuing impact of cancer and the remarkable pace of innovation in how it is treated.

Cancer is still the 2nd leading cause of death globally, with the disease causing many complications for treatment, such as its ability to spread throughout the body and the composite nature of tumours. However, there have been many recent advances which are providing hope for victims of cancer, from robotic surgery to advanced cell and gene therapies.

In honour of World Cancer Day, this article will showcase some of the cutting-edge innovations which have the potential to transform patients’ lives, improving accuracy and accessibility.

Innovation in oncology

Cell therapies

Cell therapies have fundamentally changed the cancer treatment landscape by harnessing the body’s own immune system to identify and destroy malignant cells. Among the most transformative developments is CAR-T (chimeric antigen receptor T-cell) therapy. CAR-T therapy has already proved successful in treating certain blood cancers and early clinical data suggests that CAR-T therapies could tackle solid tumours, which account for about 90% of all cancers and are notoriously difficult to treat due to their complex mix of cell types.

Next-generation cell therapies are showing a shift towards “off-the-shelf” treatments. This points towards a future where treatments can be produced and delivered at scale and to a much tighter timeframe, making them more accessible for patients. Mass-production is achieved through allogeneic (as opposed to autologous) sources, meaning the implanted and edited cells originate from a healthy donor rather than the patient.

In December, the New England Journal of Medicine released results of a trial in which patients received “universal” CAR-T cells. The cells were taken from a healthy donor and then genetically modified, generating a storable cache for cell therapy. The universal CAR-T cells showed promising results in treating an aggressive form of blood cancer, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. As this cancer occurs because of abnormal T-cells, it is difficult to target with autologous T-cell therapy.

Scientists are also developing treatments with other types of cells, such as natural killer (NK) cells. NK cells can selectively attack abnormal cells, fighting cancer without triggering an extreme immune response. Advances in synthetic biology are making it possible to generate these cells using donated blood stem cells. Evidence suggests that one donor could potentially provide enough cells for thousands of treatments.

Antibodies and anti-drug conjugates

Antibody-based therapies remain a cornerstone of modern oncology. Monoclonal antibodies such as pembrolizumab, nivolumab, ipilimumab and trastuzumab have become standard-of-care in multiple indications, validating decades of investment in immune checkpoint inhibition and targeted therapy, and illustrating how long-term patent protection has underpinned sustained development in this area.

Recently, the innovation landscape has focused more heavily on antibody-drug conjugates, addressing targets which were previously considered undruggable. ADCs can deliver chemotherapy agents directly to cancer cells, again improving the level of precision to minimise the side effects which come with cancer treatment.

Cancer surgery

Approaches to tackle cancer are not just limited to pharmaceuticals; some tumours can be extracted from the body through surgical procedures. However, surgery is high-risk, and factors such as the position or composition of a tumour makes surgery in some cases impossible.

New technologies such as robotic systems and laser devices could make operating on tumours in places with restricted access feasible. Lasers can destroy tumours precisely without damaging healthy tissue, whilst robotic devices can reach places which traditional surgical tools cannot.

Researchers at the University of Oxford have developed another way to improve accuracy in surgery: a fluorescent dye which highlights cancerous tissue, including tissue which is not detected by standard imaging. This makes it easier for surgeons to find and remove malignant tissue, whilst minimising unwanted damage.

AI and diagnostic procedures

Diagnostics are also becoming more accurate, as well as less invasive. For example, liquid biopsies are non-invasive and can be more informative compared to the traditional method of surgically removing a piece of tissue or a sample of cells from the body for diagnostic purposes. Thanks to technological advances, tumour DNA fragments can be detected in blood samples. Last year, the NHS was the first in the world to implement a new liquid biopsy test for patients with lung and breast cancer, enabling the delivery of more personalised and streamlined care.

AI is becoming a core tool in efficient and effective healthcare, and cancer diagnosis is no different. AI can be used to interpret X-ray, CT, MRI and PET imaging to flag subtle abnormalities early and with high precision. The NHS has launched trials exploring how AI can improve the breast screening system, and it has just been announced that they will also be trialling AI in lung cancer diagnosis – the cancer responsible for the most deaths in the UK.

The combination of AI and less invasive methods of detection has the potential to transform the way we spot cancer in patients, bringing us closer to instant and autonomous screening. This could lead to earlier discovery and, ultimately, better treatment and a lower death rate.

Patent protection in oncology

Innovation in oncology can be costly and time-intensive. Taking a clinical candidate from bench to bedside can take many years and requires substantial investment in research, trials, regulatory approval and manufacturing. Therefore, patent protection is therefore both for securing early investment and for later recouping the costs of developing new treatments.

Patenting a new cancer treatment

A common starting point for patent protection in oncology innovation is a new therapeutic agent. The precise scope of protection available will depend on what new data has been generated, and what is already known about the same or similar agents. In addition, innovators typically build a portfolio of patent applications around a single agent over time. Such applications may be directed to:

- Compositions of matter protecting the therapeutic agent itself, often with broad medical use claims where available. These applications usually provide the strongest protection.

- Further medical uses of the agent. As development progresses, the innovator may discover that the agent is effective in treating a different cancer that was not previously recognised. A new patent application directed to this new therapeutic use may be filed, even if the agent is already publicly known.

- Formulations that improve stability, delivery, tolerability or targeting of the agent.

- Dosage regimens protecting specific dosing schedules or administration protocols of the agent.

Taken together, these different types of patent applications can form a layered protection strategy around the therapeutic agent.

What else can be protected?

Focusing only on new therapeutic agents can risk overlooking other forms of patentable subject matter in oncology. For example, although diagnostic methods are excluded from patentability in some jurisdictions, this does not mean useful protection is unavailable. Instead, diagnostic methods often require more careful claim drafting, for example, by directing claims to in vitro methods. Similarly, while methods of surgically removing a tumour may not be patentable, the tools that enable the procedure are frequently AI-driven technologies, for example, in imaging analysis, which can also form part of a valuable patent portfolio if framed correctly.

Opposition and validity challenges

Given the commercial importance of oncology patents, European patents in this field are frequently subject to opposition at the EPO. The opposition procedure provides a centralised mechanism for third parties to challenge the validity of a patent within nine months of grant. The outcome can often turn on the quality of the technical and legal arguments advanced, and the manner in which the patent is amended and defended. Beyond this period, validity may still be challenged through national revocation actions or centrally before the Unified Patent Court (UPC).

Whilst World Cancer Day is a time to acknowledge the serious impact which cancer still has on many people’s lives, it also reminds us of the extraordinary progress across the oncology landscape. Innovation is reshaping cancer care in ways that were unimaginable only a decade ago, gradually improving outcomes for patients.

Patent protection will continue to play a pivotal role, shaping how discoveries are protected, developed and delivered to patients. As therapies and diagnostics become more complex and interconnected, thoughtful patent strategy will be essential to ensure that innovation translates into real-world impact for patients.

SpaceX is reportedly going public, in what may be one of the largest IPOs ever. What do we know about its patent portfolio? And what can we learn from its patent strategy?

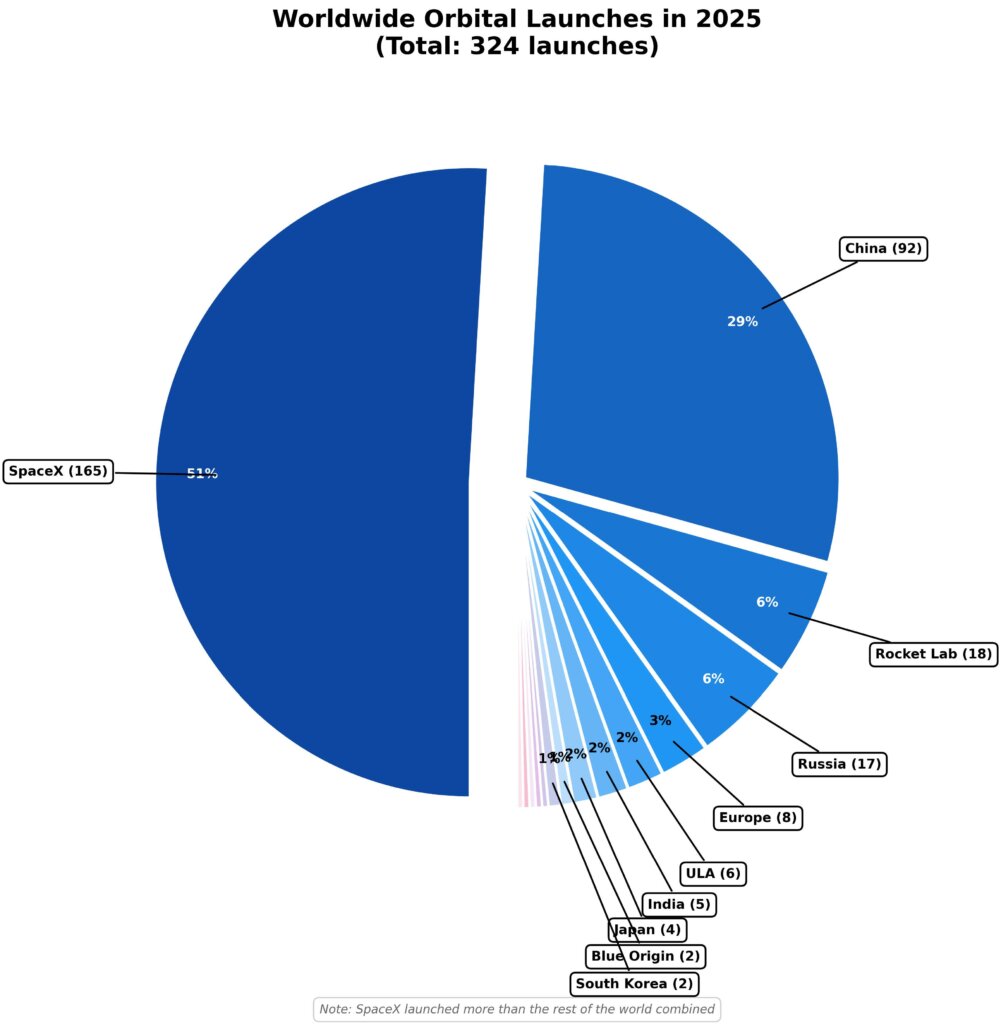

Since its founding in 2002, SpaceX has become the world’s dominant space company. The competition, for now, is not even close. Founded with the aim of significantly decreasing the costs of launching into orbit, saved from bankruptcy by the timely securing of generous government contracts to supply the international Space Station, SpaceX has been a media fixture with dramatic innovations, including the reusable Falcon 9 launch vehicle and the ‘chopsticks’ landing of its successor, Starship. SpaceX now averages 2-3 launches every week; in 2025, it was responsible for 50% of all orbital launches worldwide, 80% of ones in the US. These figures seem only likely to increase in the near term as even competitors find themselves relying on SpaceX to launch their satellites.

Now its CEO, Elon Musk, is said to be pondering taking SpaceX public. With an estimated valuation which has surged in the last year from $400 billion to $800 billion and some think could even reach $1.5 trillion, it would be one of the largest IPOs in history. What the billions expected to be raised from the sale would be used for is anyone’s guess. Some speculations are developing data centres in space to support the incessant demands of AI, aligning Musk’s other ventures xAI and Tesla for an anticipated convergence of AI and robotics technologies, or perhaps space manufacturing, and the stated ultimate goal: Mars. The plans would no doubt be grand.

SpaceX’s patent portfolio

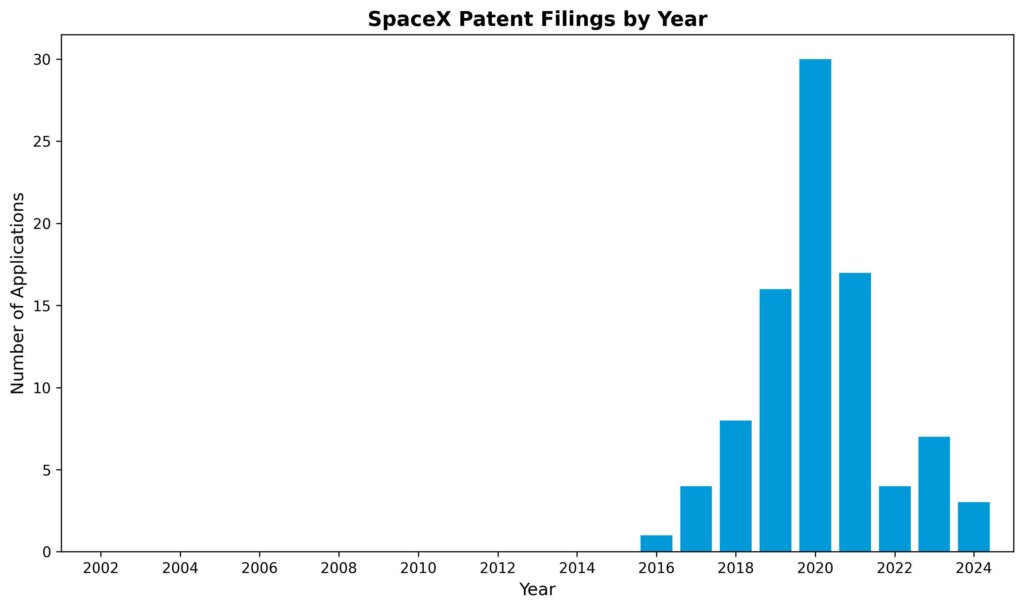

SpaceX’s patenting strategy is perhaps not what one might expect; its patent portfolio

proves to be almost as idiosyncratic as its founder.

What is formally the Space Exploration Technologies Corp has a portfolio of nearly 100 distinct patent families. However, for over a decade of initial development SpaceX was not pursuing patent protection at all. Whatever the truth about Musk’s oft-quoted quip at the time that patents were “for the weak”, this position has evidently changed.

Why the change? Starlink. Since first launching in 2019, the wholly-owned subsidiary, with its constellation of now over 9,000 satellites providing internet connectivity worldwide, has itself grown to a dominant position, being responsible for two-thirds of active Earth-orbiting satellites. Starlink has been critical in providing SpaceX with a steady source of income.

SpaceX’s patent filings now span various technologies relating to satellite communications, including antennas, printed circuitry, transmission systems and waveguides. This makes sense for technology implemented in widely available consumer products. There are even some design patents for the distinctive Starlink antennas. What is notably missing is any patent coverage for the launch systems themselves, whether for the rocket engines (Raptor, Draco), launch vehicles (Falcon, Starship) or spacecraft (Dragon).

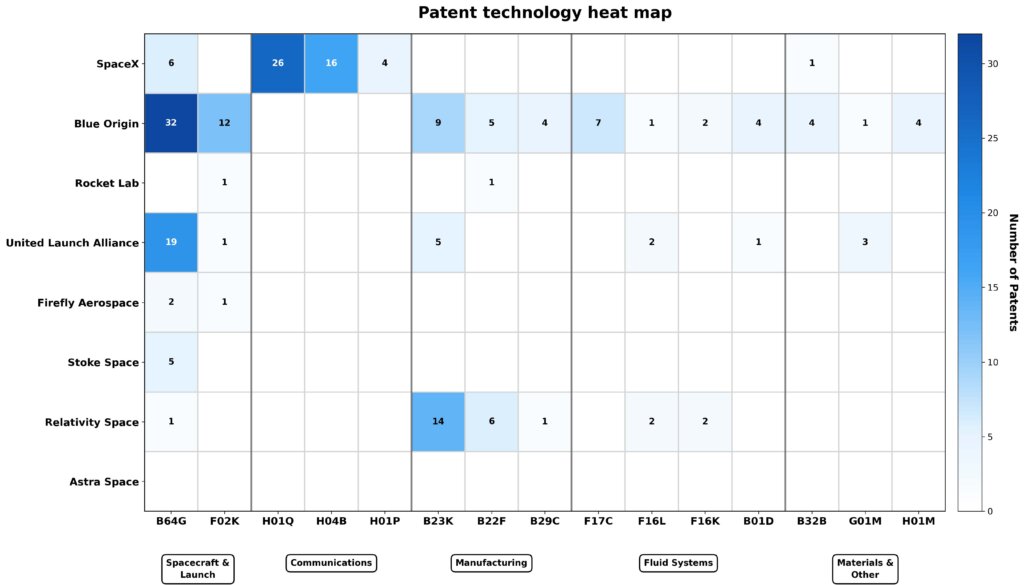

A look at SpaceX’s competitors

SpaceX’s strategy is at odds with its launch start-up competitors, of which there are increasingly many. The burgeoning commercialisation of space has led to a flurry of space start-ups developing launch capability, at least two of which – Jeff Bezo’s Blue Origin and Rocket Lab – feature in the worldwide top-ten of launch providers (ULA, the United Launch Alliance, is actually a joint-venture between established aerospace giants Lockheed Martin and Boeing). Launching into orbit is no longer the exclusive provision of nation states.

When we compare the subject matter of patent filings, we find these competitors – Blue Origin in particular – are seeking patent protection for a broad range of launch-related technologies, including manufacturing, fluid systems and materials. Not so SpaceX, which has focused exclusively on Starlink.

Mapping SpaceX’s patents

Another curiosity is where SpaceX file for patents. As would be expected for a US-based company (and all SpaceX employees are required to be US citizens), initial patent applications are filed in the US. However, interest in patent rights beyond the US is very limited: only a dozen international applications, barely a third of the portfolio pursued elsewhere, essentially only in Germany and Taiwan. This is a highly geographically targeted patent filing strategy: protection for where there is relevant

The lack of patent protection beyond the US suggests perhaps some confidence at SpaceX that any non-US companies will not become commercial competitors within any realistic timescale, even allowing for the maximum 20-year patent term.

An evaluation of SpaceX’s patent strategy

While we can only speculate as to why SpaceX has avoided seeking patent protection for what might be considered its core technology, the lack of a comprehensive patent portfolio adds to the difficulty of assessing the long-term worth of SpaceX. In the near-term, Starlink appears to be more valuable on account of its steady income stream. Yet it is the launch capabilities which are the crown jewels and those appear to be unprotected by patents.

Admittedly, patents directed to the launch systems may be difficult to enforce, especially once launch has occurred and it becomes difficult to secure physical evidence of any infringement. Also, the applicability of patent law in space is not always clear. While the US has amended its patent law to supposedly extend to space, many other countries have not.

A more prosaic reason comes from another Musk quote, that he does not want to provide a “recipe book” for competitors, referencing China specifically; patent specifications require a full disclosure of the pertinent technical details.

Instead, SpaceX appears to protect its IP in launch technology via trade secrets. This comes with its own risks.

Although some SpaceX employees have over a decade of service, a demanding work schedule and culture differences (and despite financial incentives to stay and disincentives to leave) mean turnover rates for those with up to 5 years of experience are high. Employment contracts may have strict IP protections provisions, but know-how and experience may nevertheless simply walk out the door. SpaceX employees would be highly valuable elsewhere, including at legacy aerospace companies.

The spectre of industrial espionage also looms large, something of which SpaceX are evidently concerned: a Russian cosmonaut was recently removed from the SpaceX crew for allegedly photographing a rocket engine and other sensitive material with a smartphone.

The future of SpaceX

Imitation, the sincerest form of flattery, is now a realistic possibility. Several commercial competitors in China, such as LansSpace, have been testing launch vehicles which appear remarkably similar to those of SpaceX. The lack of formal IP protection there leaves everything open to copying.

Starlink, too, is not immune from competition. Others are sensing commercial opportunities; nation states do not want to become reliant on a single provider led by a mercurial CEO. Both are deploying constellations of their own: Amazon with its Kuiper and TeraWave; China (which blocks Starlink) has SpaceSail. Even Europe is getting in on the act with OneWeb. Such is the number of LEO satellites planned that there are genuine concerns that the Kessler Syndrome, where the amount of space debris that makes certain orbits unstable, will become a reality.

The risk to SpaceX’s dominance is clear. And there is form: Tesla is no longer the world’s largest electric vehicle company; BYD is.

Final thoughts

What can we conclude? That for a technology company patents are only one tool. It is entirely possible to operate with a hybrid approach: patents to protect income streams, especially if dependent on technology which is straightforward to reverse-engineer, geographically targeted at potential rival manufacturers; trade secrets for core technology which may be difficult to protect anyway.

There is another reading. SpaceX is sui generis. Whether its patent strategy can be used by other companies is unclear. Few companies can draw on the Musk celebrity which is an intrinsic part of the way SpaceX operates. But technology leads are not eternal; many once ubiquitous companies – Kodak, Blackberry, perhaps now Intel – have found themselves losing their way and being overtaken. Likewise SpaceX’s lead, which may at present appear unassailable, is likely only temporary. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why SpaceX might be going public sooner rather than later.