The launch of Mathys & Squire Consulting follows the exciting acquisition of leading IP consulting firm Coller IP in 2017, when Mathys & Squire sought to develop its IP strategy and valuation service line.

Since this acquisition, the two firms have developed their relationship to a point at which their legal and commercial services fit seamlessly together, and are now in a position to bring these resources in-house, offering clients a one-stop-shop experience for all IP matters under the Mathys & Squire umbrella. From today, 14 April onwards, the existing Coller IP team will be integrated into Mathys & Squire, bringing together the expertise and experience of both businesses.

Commenting on the news, partner Alan MacDougall said: “Having an IP strategy in place is an integral part of any successful business, and we are proud to be able to offer our existing and prospective clients the full range of commercial IP advice and services they need to help their business grow under the Mathys & Squire umbrella. Being part of the innovation environment means we are always seeking to identify innovative ways of enhancing our range of services to clients and help them manage all IP aspects of their businesses.”

For further information, download our Mathys & Squire Consulting services brochure here.

Coverage of the Mathys & Squire Consulting launch has been featured in articles by Intellectual Property Magazine, World Trademark Review and The Patent Lawyer (registrations required).

Like many patent offices, the EPO does not allow applicants to claim methods for treatment of the human or animal body by surgery or therapy (Article 53(c) EPC). Such exclusions are historically founded upon the principles of free exercise of the medical profession. The EPO has, nevertheless, allowed applicants to navigate around such exclusions by protecting new and innovative medical treatments by means of purpose-limited product claims (i.e. “compound X for treatment of disease Y”), where the use to which the claim is directed determines patentability.

The claiming of non-therapeutic (e.g. cosmetic) methods (rather than purpose-limited product claims) is allowed at the EPO. However, such claims have not always been so readily accommodated under EPO practice, specifically where there is the potential for a non-therapeutic method to have an underlying (even if unintended) therapeutic benefit. Once there is considered to be an inevitable therapeutic element to any such method, the exclusions relating to methods of treatment have often prevented applicants successfully pursuing such claims at the EPO, even if there is a legitimate intent not to cover a therapeutic treatment.

However, a recent decision from the technical Boards of Appeal of the EPO – T1916/19 – suggests that the EPO may be becoming more accepting of such claims, which will be welcome news to certain innovators, particularly those operating in the cosmetic, functional food or nutraceutical fields, for instance. This article discusses the background and some of the more interesting developments in EPO case law around non-therapeutic method claims, particularly where the non-therapeutic application is accompanied by a possibility for a potential therapeutic benefit.

In general, a method may only be considered to be therapeutic at the EPO if it involves the curing of a disease or malfunction, or has a prophylactic (i.e. preventative) effect (EPO Board of Appeal Decision T 19/86 holding that both prophylactic and curative treatments of diseases are within the meaning of the word “therapy”). Historically, the EPO has allowed applicants to exclude unpatentable therapeutic treatments from a non-therapeutic method claim by means of a disclaimer. In Board of Appeal decision T 36/83, for instance, a claim directed to “Use as a cosmetic product of thenoyl peroxide” was found to be allowable – the Board considering the “cosmetic” disclaimer to be sufficient to separate the subject-matter of the claim from the medical use of thenoyl peroxide. In particular, the Board in that case commented:

“To avoid any possible conflict with the provisions of Article 52(4) EPC in a use or indication claim, it would have been possible to envisage the exclusion of the non-patentable invention within the meaning of that article by means of a disclaimer. In the present case the Board considers use of the term “cosmetic” to be sufficiently precise.”

The Board’s decision in T 36/83 was influenced by the distinction, clearly set out in the description of the application as filed, between the therapeutic and non-therapeutic methods (Reasons for the Decision point 6). It may therefore, on first sight, seem that there should be no great barrier to the protection of various non-therapeutic methods, if the applicant can rely on disclaimers to exclude any potential non-patentable methods of treatment. However, complexity arises when a method potentially provides for both therapeutic and non-therapeutic effects.

Established EPO case law (e.g. Board of Appeal decision T 290/86) has historically stipulated that non-therapeutic methods must be directed solely to a non-therapeutic effect so as not to encompass anything that falls foul of the exclusions directed towards therapeutic methods. In T 290/86, a cosmetic treatment relating to the removal of plaque from teeth was not considered allowable as this method was considered to inevitably have a therapeutic effect of preventing tooth decay. In taking this line, the Board deviated from an earlier decision – T 144/83 – which concerned a weight loss drug that was able to provide both a cosmetic weight loss effect, as well as a therapeutic cure for obesity. Whilst the Board in T 144/83 acknowledged that the two uses were “adjoined”, it was felt that this should not be allowed to work to the disadvantage of an applicant claiming protection for the cosmetic method.

One notable difference in the formulation of the claims in T 144/83 (appetite suppressant) and those of T 290/86 (plaque removal) was a reference to attaining a “cosmetically beneficial” result in the earlier case, which may have helped the Board reach the conclusion it did. Nevertheless, the use of disclaimers to carve out non-therapeutic methods has had mixed results before the EPO, where there has been the potential for therapeutic effects to accompany the non-therapeutic benefits of an invention. Where non-therapeutic and therapeutic uses have been considered to be “inseparably associated” with each other (T 1635/09), a disclaimer to the therapeutic use in a claim has either been considered to have no effect in isolating the non-therapeutic use or has been considered to mean that the whole subject-matter of the claim is in effect disclaimed so as to be completely void (T 767/12) – leading to a fundamental lack of clarity in either case.

Decision T 1635/09, for instance, concerned use of an oral contraceptive for a woman of fertile age making use of a low oestrogen dosage. Whilst it is worth noting that the EPO does not consider contraception to be a medical method, use of the low oestrogen contraceptive in question was nevertheless seen to encompass a medical treatment because the technical problem solved by the invention was one of reducing harmful side effects, as compared to a higher oestrogen dosage, rather than an increased efficacy of contraception. Thus, although the claim related to a contraceptive use which is non-therapeutic per se, the selected concentrations of active substance defined in the claim simultaneously prevent pathological secondary effects likely to arise in the case of that contraceptive use (and passages in the applicant’s own application outlining the advantageous reduction in pathological side effects were considered particularly relevant). The presence of a “non-therapeutic” disclaimer in the claim was thus considered to be insufficient to overcome an objection under Article 53(c) EPC in view of the inseparable association with an unpatentable method of treatment.

These cases demonstrate that separating therapeutic and non-therapeutic methods in a claim is not always straightforward, and this is particularly the case where the potential therapeutic benefit relates to prophylaxis (i.e. preventative treatment). In decision T 780/89, claims to the use of certain compounds for non-therapeutic immunostimulation were found not to be allowable. The Board in that case took the view that immunostimulation, or stimulation of the body’s own defences, constituted a prophylactic treatment because infection is prevented. Since the therapeutic use could not be separated from the non-therapeutic use, the inevitable therapeutic/pharmacological effect of the active substance could not be cancelled out by the use of the “non-therapeutic” disclaimer.

Nevertheless, in decision T 358/09, use of a “non-therapeutic” disclaimer was allowable and considered able to differentiate a claim directed to a non-therapeutic method of cooling cows to lure them to a milking stall from an excluded medical method of cooling cows as a treatment for overheating. The Board in that case opined that the purpose of therapy was invariably to restore the organism from a pathological state to its original condition, or to prevent pathology in the first place, whereas a non-therapeutic improvement of performance took as its starting point a “normal state”.

However, it is not clear how much consideration was given to the potential prophylactic benefit associated with the method in T 358/09. If prophylaxis is to be defined as preventing a pathological state by maintaining the “normal state”, it would seem that there is a far greater opportunity for overlap of non-therapeutic and prophylactic uses, and in some cases it may be more of challenge to carve out the non-therapeutic use in a claim. Does it, for instance, matter how much at risk a subject might be of developing a disease/pathology, when considering whether a potential prophylactic benefit may also arise as a result of a non-therapeutic method?

Recent decision T 1916/19 could therefore be a welcome development to certain innovators, since it appears to signal that there must be a real possibility of a prophylactic benefit for a healthy subject in order for this to prevent the legitimate claiming of a non-therapeutic method (i.e. for therapeutic and non-therapeutic effects to be considered genuinely “inseparable”). In this decision, the claimed invention related to a non-therapeutic method comprising the application of an anti-microbial composition to the skin for the purpose of improving body odour. Whilst this method is primarily a cosmetic treatment, the Examining Division refused the application at first instance on the basis that pathogenic bacteria would be removed as an inevitable result of carrying out the method. As a consequence, the claim scope was seen to impermissibly cover prophylaxis against infectious agents by the Examining Division, meaning the claim impermissibly embraced a method of treatment.

In following this line, the Examining Division saw therapeutic and non-therapeutic effects of the anti-microbial skin treatment as being “inextricably linked”, i.e.one would occur as an inevitable result of carrying out the other. Nevertheless, on appeal the Board in T 1916/19 ultimately reversed the decision of the Examining Division, accepting the appellant’s arguments that removal of pathogenic bacteria from a healthy person’s skin does not in fact constitute a prophylactic treatment. In reaching its decision, the Board acknowledged (point 4.6.1 of the Reasons) that:

“Undoubtedly, at least some realisations of the claimed method of providing an anti-microbial effect on skin are therapeutic in nature, e. g. in case the composition is applied to individuals suffering from a bacterial skin infection or a wound. There may be also realisations of the method which, depending on the circumstances, may be of a therapeutic/prophylactic nature or not, e. g. applying the composition to the hands…”

The Board, however, went on to state (point 4.6.2 of the Reasons) that:

“Even in case potentially pathogenic bacteria are present on its skin a healthy individual is not likely to develop a pathological state only because of the presence of such bacteria. Not disinfecting one’s armpits or feet may have unpleasant consequences, but will not, as such, lead to a pathological condition.”

Whilst it could of course be argued that the presence of a pathogen on the body poses a non-zero degree of risk in developing a pathology, the Board clearly felt this risk to be negligible, meaning that the claimed method was not “inseparably associated” or “inextricably linked” with a method of prophylaxis and the Board went on to conclude (point 4.6.3 of the Reasons):

Thus, the Board does not share the reasoning of the Examining Division that the claims only define methods in which non-therapeutic and therapeutic effects are inextricably linked.

The Board comes to the conclusion that there are realisations of the claimed methods that are of a non-therapeutic nature, others that are of a therapeutic nature, and others that may be mixed.

In this scenario, the Board considered the disclaimer in the claim limiting to non-therapeutic methods to be allowable and also capable of excluding therapeutic methods, thereby avoiding contravention of Article 53(c) EPC, and the Board remitted the case back to the Examining Division for further examination accordingly.

This case is interesting in as much as the Board acknowledged that there are certain “realisations” of the claimed method that involved therapy/prophylaxis, but it seems that the Board was satisfied that there are alternative “realisations” of the method that do not, ostensibly where the method is applied to a “healthy individual” (presumably exhibiting the “normal state” as referred to in T 358/09 (cow cooling case)).

One question that arises as result of T 1916/19 is to what extent the possibility of prophylaxis can exist before there can be considered an “inextricable link” between the claimed method and a therapeutic/prophylactic treatment. In other words, what proportion of the possible “realisations” of the claimed method need to necessarily involve a prophylactic element, for prophylaxis to be “inextricably linked” with the method? This seemingly puts a focus on the scope of the “healthy individual” to which the non-therapeutic method is applied and whether prophylaxis would be inherent having regard to that subject.

It therefore seems that further development in the case law might be required to understand the full impact of T 1916/19 on the assessment of non-therapeutic methods going forward. Nevertheless, this case offers some reassurance to applicants that the possibility of a prophylactic benefit to a claimed non-therapeutic method does not automatically preclude the allowability of the non-therapeutic method, particularly where any prophylactic benefit might be remote or would not be enjoyed by a healthy subject to which application of the non-therapeutic method is intended. This seems like a pragmatic approach to the assessment of non-therapeutic methods in order to avoid applicants being unfairly disadvantaged and so as not to stifle legitimate innovation.

Another consideration that T 1916/19 opens up is whether applicants can more freely claim a non-therapeutic method, as well as a therapeutic use in treating a specific patient group that could feasibly take a prophylactic (or other therapeutic) benefit (i.e. in certain “realisations” of the method) in the same patent application. The current state of EPO case law does support this possibility. For instance, in decision T36/83, it was stated:

“A product’s first use in a method of treatment of the human or animal body by therapy and also its use cosmetically may therefore be claimed in one and the same patent application”

However, as discussed above, such allowability would appear to be conditional on the therapeutic and non-therapeutic uses not being “inextricably linked” or “inseparably associated” with each other. It also remains to be seen whether the existence of such medical use claims in the same patent application could potentially undermine arguments that any possible prophylaxis in the case of the non-therapeutic method claimed was sufficiently remote from the “healthy individual” to which the non-therapeutic method was directed. Consequently, it is likely that in such cases careful construction of the patent application at the drafting stage will be of paramount importance in placing the application in the best possible position in order for non-therapeutic and therapeutic uses to be successfully claimed in the single application.

We at Mathys & Squire have seen several examples of such cases nevertheless making it through EPO examination. For instance, EP3316876 B1 (“Arginine Silicate Inositol for Improving Cognitive Function”) granted with the following claims:

“Inositol-stabilized arginine silicate for use in treating and/or preventing a cognitive disorder in a subject”; and

“A non-therapeutic method of improving cognitive function in a subject comprising administering inositol-stabilized arginine silicate to the subject”.

In this case, the treatment of a subject in need of cognitive enhancement in order to return to, or maintain, a “normal state”, e.g. patients suffering from dementia, can be separated from healthy individuals simply making use of a method of improving cognitive function over the normal state, meaning that both claims were found to be allowable in the same patent application.

Clearly, the specific technical facts underpinning inventions having both therapeutic and non-therapeutic elements will play a large part in whether a claim to the non-therapeutic method is allowable (and whether therefore an alternative therapeutic use may be claimed in the same patent application). Nevertheless, applicants may be encouraged that the EPO will take a more pragmatic approach to assessing such claims in the future, to the benefit of innovation.

For further information, visit our Life sciences & chemistry page, or contact the author, Michael Stott, directly.

In this article for PCR, Mathys & Squire Partner Andrew White and Technical Assistant Conor McGuinness, look at the patentability of computer games in Europe and the UK and address the common misconception that computer games are not patentable.

It was announced recently that US video game publisher, Electronic Arts has agreed to purchase UK-based video game publisher Codemasters for approximately $1.2 billion. UK-based companies are, therefore, clearly playing a leading role in video game development and publication. The UK consumer market is of similar scale. The UK gaming market is currently the sixth biggest globally with UK consumers spending an estimated £5.35 billion on game hardware and software.

As the UK video game industry looks set to only grow, developing a bespoke intellectual property (IP) strategy is of the utmost importance. Obtaining suitable IP rights provide you with the opportunity to ‘fence off’ your innovations from competitors and potentially lock-in your customers. IP rights can also significantly push up the value of your company.

Patenting computer games in Europe

In essence, a modern computer game is a piece of software describing a set of abstract game rules configured to be executed by hardware such as a PC or a games console. The European Patent Office (EPO) will grant patents to inventions that they consider provide a technical solution to technical problem, but does not recognise, among other things, programs for computers, playing games or mathematical methods, in and of themselves as inventions (Art. 52 (2),(3) EPC).

On the face of it, the ability to obtain patent protection for computer games, therefore, looks bleak.

However, the EPO will consider a computer program product an invention (and, therefore, potentially patentable) if, when it is run on a computer, it produces a further technical effect which goes beyond the ‘normal’ physical interactions between program (software) and computer (hardware) (see Headnote of T 1173/97).

So, when it comes to video games, although patents cannot be sought for the rules of a game in and of themselves, there may be patentable subject-matter in the way the rule of the game are implemented, provided there is some technical effect which goes beyond the ‘normal’ physical interactions between program and computer.

What is patentable?

As an example of what is considered to be patentable, an application claiming a game wherein the probability for a character appearing on a game map was varied was, in contrast to the previous case, found to be patentable. The probability calculation was considered to be technical because it solved the problem of how to modify the game program such that it generated encounters in a less predictable manner (see T 0012/08).

As another example, it was found that a guide display device for use in a video game system was allowable subject-matter. In more detail, the guide display device highlighting a first character so that the player could identify them and also a pass guide mark which allowed identification of a second character to whom a ball is to be passed. The pass guide mark continued to be displayed on the edge of the display area when the second character left the visible area. It was argued that the technical problem here related to conflicting technical requirements, namely: a portion of an image is desired to be displayed on a relatively large scale (e.g. zoom in); and, the display area of the screen may then be too small to show a complete zone of interest. which has to be considered in the inventive step discussion. The Board asserted that resolving the conflict by technical means implies a technical contribution (T 0928/03).

From the above review, it is clear that computer games, or at least aspects of the computer games, are patentable. Bearing in mind the size of the potential UK market, computer game developers and publishers should be actively considering the patentability of their creations, as part of a wider holistic IP review that also includes other IP rights such as trade marks, copyright and confidential information.

This article was originally published in PCR Magazine in March 2021.

A new edition of the EPO Guidelines for Examination (‘the guidelines’) came into force on 1 March 2021. Relevant to life sciences, this edition includes a new subsection detailing EPO practice with respect to the interpretation of terms relating to amino or nucleic acid sequences, as well as a new section on the examination of claims to antibodies.

Terms in relation to amino or nucleic acid sequences (F-IV, 4.24)

In the field of biotechnology, claims often include nucleotide or amino acid sequences that are defined in terms of their percentage identity or percentage similarity (amino acid sequences only) to a specified reference sequence. The new guidelines now provide written guidance on how these different terms are interpreted.

Firstly, they confirm that when an amino acid or nucleic acid sequence is defined by using percentage sequence identity language, this is determined by the number of identical residues over a defined length in a given alignment. If no algorithm or calculation method for determining the percentage of identity is defined, the broadest interpretation will be applied using any reasonable method known at the relevant filing date.

In addition, it is confirmed that amino acid sequences can also be defined by a degree of similarity, expressed as a percentage of similarity. Similarity is considered broader than identity, as it allows conservative substitutions of amino acid residues having similar physicochemical properties over a defined length of a given alignment. The percentage of similarity is determinable only if a similarity-scoring matrix is defined. If no such matrix is defined, a claim referring to a sequence displaying a percentage of similarity to a recited sequence is considered to cover any sequence fulfilling the similarity requirement as determined with any reasonable similarity-scoring matrix known at the relevant filing date.

Finally, for amino acid sequences, the guidelines now state that if a percentage of homology is used by the applicant as the only feature to distinguish the subject matter of a claim from the prior art, its use is objected to under Article 84 EPC unless the determination or calculation of the percentage of homology is clearly defined in the application as filed. However, for nucleic acid sequences, homology percentage and identity percentage are usually considered to have the same meaning.

Antibodies (G-II, 5.6)

A new section, summarising EPO practice and case law on how an antibody may be defined (e.g. by sequence, functional feature, or epitope), and the inventive step requirement for new antibodies binding to a known antigen, has also been included in the 2021 guidelines.

Claiming antibodies

They also outline how conventional antibodies, recombinant antibody derivatives (such as antibody fragments, bispecific antibodies or antibody fusions) or new antibody formats (such as heavy-chain-only antibodies) can be defined in a claim by reference to one or more of the following features:

(a) their own structure (amino acid sequences);

(b) nucleic acid sequences encoding the antibody;

(c) reference to the target antigen;

(d) target antigen and further functional features;

(e) functional and structural features;

(f) the production process;

(g) the epitope; and

(h) the hybridoma producing the antibody.

Definition by structure of the antibody

Conventional antibodies defined by their structure are to be defined by at least six complementary-determining regions (CDRs). CDRs, when not defined by their specific sequence, must be defined according to a numbering scheme, for example, chosen from that of Kabat, Chothia or IMGT. If the claim has fewer than six, it will be objected to under Article 84 EPC because it lacks an essential technical feature. An exception applies only if it is experimentally shown that one or more of the six CDRs do not interact with the target epitope or if it concerns a specific antibody format allowing for epitope recognition by fewer CDRs (such as the heavy-chain-only antibodies which have an antigen-binding region with only three CDRs).

Definition by reference to the target antigen

An antibody can be functionally defined by the antigen it binds to, as long as the antigen is clearly defined in the claims. If the antigen is defined by a protein sequence, no sequence variability and no open language (e.g. ‘comprising’) can be used in the definition of the antigen. Examples of accepted antigen-defined antibody claim wording are:

(i) antibody binding to X;

(ii) anti-X antibody;

(iii) antibody reacting with X;

(iv) antibody specific for antigen X; or

(v) antibody binding to antigen X consisting of the sequence defined by SEQ ID NO:Y.

Definition by target antigen and further functional features

Antibody claims can be further characterised by functional features defining further properties of the antibodies; for example, the binding affinity, neutralising properties, induction of apoptosis, internalisation of receptors, inhibition or activation of receptors. The burden of proof of novelty resides with the applicant and it has to be carefully assessed whether the application provides an enabling disclosure across the whole scope claimed and whether the functional definition allows the skilled person to clearly determine the limits of the claim.

Definition by functional and structural features

Antibodies can also be defined by both functional properties and structural features. It is possible to claim an antibody characterised by the sequences of both variable domains or CDRs with less than 100% sequence identity when combined with a clear functional feature.

Definition by the production process

Antibodies can be defined by the process of their production; for example, either by the immunisation protocol of a non-human animal with a well-characterised antigen or by the specific cell line used to produce them. However, if the process is based on an antigen comprising a sequence less than 100% identical to a defined sequence, it does not fulfil the requirements of Article 84 EPC because the use of variants renders the scope of the antibodies obtained by the immunisation process unclear.

Definition by the epitope

An antibody may be defined by its epitope. If the epitope is a ‘linear epitope’, whereby the antibody interacts with continuous amino acids on the antigen, it needs to be defined as a clearly limited fragment using closed wording, such as ‘an epitope consisting of’. If the epitope is ‘non-linear’ or ‘discontinuous’, whereby the antibody interacts with multiple, distinct segments from the primary amino-acid sequence of the antigen, the specific amino acid residues of the epitope need to be clearly identified.

Inventive step

The new guidelines now state that a novel, further antibody binding to a known antigen does not involve an inventive step unless a surprising technical effect is shown by the application, such as an improved affinity, an improved therapeutic activity, a reduced toxicity or immunogenicity, an unexpected species cross-reactivity, or a new type of antibody format with proven binding activity.

If inventive step relies on an improved property in comparison to the antibodies of the prior art (which must be enabled), the main characteristics of the method for determining the property must also be indicated in the claim or by reference to the description. Notably, in the case of binding affinity, the structural requirements for conventional antibodies inherently reflecting this affinity must typically comprise the six CDRs and the framework regions because the framework regions also can influence the affinity.

An inventive step can also be acknowledged if the application overcomes technical difficulties in producing or manufacturing the claimed antibodies.

A version of this article was published by Life Sciences IP Review in April 2021.

Further to our article in July 2020 on the EPO Enlarged Board of Appeal’s hearing in G1/19, the Enlarged Board has now published its long-awaited decision relating to the patentability of computer-implemented simulations. While the decision specifically relates to computer-implemented simulations, it is likely to have implications for the assessment of technicality and inventive step across the whole field of computer-implemented inventions.

In short, the conclusions are that:

- in principle, computer simulations can be patentable (this was generally as expected/hoped);

- the mere fact that a simulation is based on technical principles underlying the simulated system is not enough to confer patentability (instead the decision seems to indicate that the intended technical purpose resulting in the alleged technical effect needs to at least be implied in the claims); and

- whether or not a design process is involved is irrelevant (as expected).

While the decision appears to indicate that computer simulations in principle may be patentable, it also indicates that in the Enlarged Board’s view most computer-implemented simulations are unlikely to be patentable as ‘most “simulations as such” may have few technical effects as far as input and output are concerned’, unless the intended technical purpose of the simulation giving rise to the alleged technical effect is at least implied in the claims. This appears to be in disagreement with T1227/05, and seems to narrow the scope of patentability of such computer-implemented simulations in future.

The decision in detail

As a re-cap, the Enlarged Board was posed three questions:

1. In the assessment of inventive step, can the computer-implemented simulation of a technical system or process solve a technical problem by producing a technical effect which goes beyond the simulation’s implementation on a computer, if the computer-implemented simulation is claimed as such?

2. [2A] If the answer to the first question is yes, what are the relevant criteria for assessing whether a computer-implemented simulation claimed as such solves a technical problem? [2B] In particular, is it a sufficient condition that the simulation is based, at least in part, on technical principles underlying the simulated system or process?

3. What are the answers to the first and second questions if the computer-implemented simulation is claimed as part of a design process, in particular for verifying a design?

The Enlarged Board slightly re-framed question 2 to only answer [2B] (holding part 2A as inadmissible) as follows:

[2B]: “For the assessment of whether a computer-implemented simulation claimed as such solves a technical problem, is it a sufficient condition that the simulation is based, at least in part, on technical principles underlying the simulated system or process?”

Answer to question 1: Patentability of simulations per se

“A computer-implemented simulation of a technical system or process that is claimed as such can, for the purpose of assessing inventive step, solve a technical problem by producing a technical effect going beyond the simulation’s implementation on a computer”.

The Enlarged Board held that computer-implemented simulations are, in principle, patentable, noting that “no group of computer-implemented inventions can a priori be excluded from patent protection.” The Board further noted that there is no statement in the EPC that a “simulation as such” is excluded as a “non-invention” in the same way that “a computer program as such” is. The Enlarged Board clarified that they understand a “simulation as such” “to be a simulation process comprising only numerical input and output (irrespective of whether such numerical input/output is based on physical parameters), i.e. without interaction with external physical reality”, distinguishing these from physical simulations such as wind tunnel experiments or processes which include the measurement of physical values, which are not simulations as such.

However, when discussing the patentability of such computer-implemented simulations, the Enlarged Board noted that “whether a simulation can solve a technical problem by producing a technical effect which goes beyond the simulation’s implementation, can be understood only in the context of the COMVIK approach” (reasons 49) which is part of “case law developed over decades” (reasons 65). When applying this, the Board noted that it is not decisive whether the simulated system or process is technical or not. Rather, it is relevant whether the simulation of the system or process contributes to the solution of a technical problem. It was specifically noted that computer-implemented simulations should not be treated differently when answering this question.

In order to assess whether the simulation contributes to the solution of a technical problem, under the EPO’s problem-solution approach one must look at the technical effect achieved by the invention, and that in the context of computer-implemented inventions, these must be technical effects that go beyond the simulation’s implementation on a computer – or in other words “any further technical effect going beyond the normal physical (electrical) interactions between the program and the computer on which the simulation is run”. The Enlarged Board further clarified that the technical effect going beyond the simulation’s implementation can be rephrased as a “technical effect going beyond the simulation’s straightforward or unspecified implementation on a standard computer system”.

In so doing, the Enlarged Board touched on the ideas of a “virtual technical effect”, a “potential technical effect” and a “tangible technical effect”, noting that they “fully support the view that a tangible effect is not a requirement under the EPC” and that potential technical effects may be considered if the data resulting from a claimed process is specifically adapted for the purpose of its intended technical use. However, the Enlarged Board noted that “either the technical effect that would result from the intended use of the data could be considered “implied” by the claim, or the intended use of the data (i.e. the use in connection with a technical device) could be considered to extend across substantially the whole scope of the claimed data processing method.” (reasons 94). The Board considered these potential technical effects therefore to necessarily become real technical effects when put to their intended use.

On a positive note the Enlarged Board did indicate that computer-implemented simulations “may contribute to technicality if they are, for example, a reason for adapting the computer or the way in which the computer operates, or if they contribute to technical effects relating to the results of the simulation” and that “the accuracy of a simulation is a factor that may have an influence on the technical effect going beyond the simulation’s implementation and may therefore be taking into consideration in the assessment under Article 56 EPC.”. However, in contrast to this, the Enlarged Board noted that “all a simulation does is provide information about the model underlying it” and that: “it would appear that most “simulations as such” may have few technical effects as far as input and output (which consist of data in “simulations as such”) are concerned.

Answer to question 2: Technical principles

“For that assessment it is not a sufficient condition that the simulation is based, in whole or in part, on technical principles underlying the simulated system or process”.

The Enlarged Board held that it is neither sufficient nor necessary that a numerical simulation is based on technical principles that underlie the simulated system or process, noting at reasons 88 that “the Enlarged Board does not see a need to require a direct link with (external) physical reality in every case” … “While a direct link with physical reality, based on features that per se are technical and/or non-technical, is in most cases sufficient to establish technicality, it cannot be a necessary condition, if only because the notion of technicality needs to remain open” (emphasis added). The Enlarged Board went on to confirm at reasons 141 that “were it sufficient … for the simulation to be based on technical principles, then computer-implemented simulations would hold a privileged position within the wider group of computer-implemented inventions without there being any legal basis for such a privilege”.

When discussing the potential patentability of such simulations in terms of their technical contribution, the Enlarged Board held at reasons 119 that: “It may be that some simulations of technical system do not contribute to inventive step. Conversely, following the COMVIK approach, it is possible to envisage simulations of non-technical system (such as weather simulations) that do contribute to inventive step”. Later at reasons 131, the Board indicated that use of weather forecast data (obtained from a simulation or modelling system) could contribute to inventive step “if the weather forecasting data is used, for example, to automatically open or close window shutters on a building.” However, while the Board stated that technical principles underlying the simulated system or process are not a sufficient condition, it indicated with reference to T625/11 (relating to nuclear fuel rods), which “implied physically controlling the real nuclear reactor underlying the simulation”, that the technical effects or potential uses of the computer-implemented simulation which may give rise to the alleged technical effects need to at least be implied by the claims, holding that “when the COMVIK approach is applied to simulations, the underlying models form boundaries, which may be technical or non-technical … they may contribute to technicality if … they form the basis for a further technical use of the outcomes of the simulation (e.g. a use having an impact on physical reality). In order to avoid patent protection being granted to non-patentable subject-matter, such further use has to be at least implicitly specified in the claim” (emphasis added).

At reasons 124, the Board again noted that: “Only those technical effects that are at least implied in the claims should be considered in the assessment of inventive step. If the claimed process results in a set of numerical values, it depends on the further use of such data whether a resulting technical effect can be considered in the assessment. If such further use is not, at least implicitly, specified in the claim, it will be disregarded for this purpose”.

In an apparent disagreement with the oft-cited decision of T1227/05 (discussed in our earlier article) the Board stated at reasons 128: “in the Enlarged Board’s view, calculated numerical data reflecting the physical behaviour of a system modelled in a computer usually cannot establish the technical character of an invention in accordance with the COMVIK approach, even if the calculated behaviour adequately reflects the behaviour of a real system underlying the system. Only in exceptional cases may such calculated effects be considered implied technical effects (for example, if the potential use of such data is limited to technical purposes)”.

Question 3: The design process

“The answers to the first and second questions are no different if the computer-implemented simulation is claimed as part of a design process, in particular for verifying a design.”

On the issue of whether a design process affects the patentability of simulation inventions, the Board commented that “a design process is normally a cognitive exercise. However, it certainly cannot be ruled out that in future case[s] there may be steps within a design process involving simulations which contribute to the technical character of the invention”. So it seems that at present the EPO would be minded to consider that a design process, if incorporated into a simulation claim, wouldn’t improve the prospects for patentability – but that they can’t say for definite that this may not change in future, and so leave the door open on this for now.

Conclusion

In summary, this rather lengthy and detailed decision seems more negative than positive. In positive terms it holds that computer-implemented simulations are patentable and should be treated no differently than any other computer-implemented inventions. However, the use of features relating to the simulation for supporting inventive step under the COMVIK approach now seems somewhat restricted (compared to that defined in previous case law such as T 1227/05) to cases where there is a need to adapt the computer or its functioning or if there is a further technical use of the outcomes of the simulation, with such further use having to be at least implicitly specified in the claim.

At the heart of many of these complex decisions lies the tricky question of what is and what is not “technical” under European patent law. Whilst the Enlarged Board had an opportunity to give guidance on this specific issue, they refrained from doing so, noting that ‘the term “technical” must remain open, not least in anticipation of potential new developments’. The Board did, however, discuss differences between computer-implemented simulations of a technical system or process and that of a natural process (such as the weather), noting that “a technical system or process implies that an object is created or a process is run with some purpose based on human creativity” – perhaps giving us some closer definition of what the term “technical” might mean.

In this article for Intellectual Property Magazine, Mathys & Squire associate Max Thoma and technical assistant Oliver Parish consider the importance of drawings in determining the scope of a registered design.

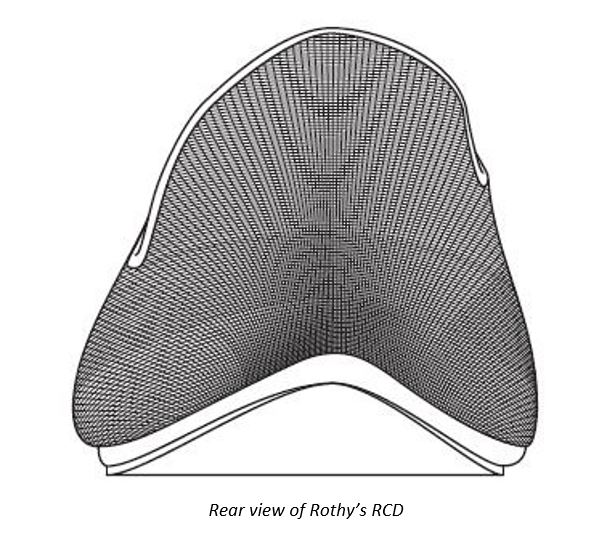

In this recent design case – Rothy’s Inc v Giesswein Walkwaren AG [2020] EWHC 3391 (IPEC) – before the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC), the judge decided that the Austrian company Giesswein Walkwaren AG’s “Pointy Flat” shoe infringed a Registered Community Design (RCD) held by the California-based fashion company Rothy’s Inc.

Background

Rothy’s claimed that Giesswein’s knitted “Pointy Flat” shoe (pictured below) infringed its RCD (also pictured below) as well as its Unregistered Community Design (UCD) rights subsisting in its own knitted “Pointed Loafer” shoe. Both of the “Pointy Flat” and “Pointy Loafer” shoes were made of a knitted fabric.

Giesswein counterclaimed for invalidity of Rothy’s RCD on the basis of two prior designs, the “Allegra K” and the “Bonnibel” shoes (pictured below). Both the “Allegra K” and the “Bonnibel” were made from suede (or variants thereof).

The Registered Community Design

The pivotal issue in dispute was how to interpret the fine black lines shown on the shoe upper in Rothy’s RCD.

The defendant, Giesswein, argued that the black lines merely showed that the shoe is a three-dimensional shape, and that if the black lines did indicate any surface design feature, that feature was a textured appearance generally (including any knitted, woven or animal hide materials, but excluding smooth textures) rather than any specific material.

The claimant, Rothy’s, encouraged the Judge to zoom in on the high-resolution digital images of the RCD which show that the black lines radiate in a circular pattern at the heel and toe of the shoe. Such a pattern, it was argued, is specifically indicative of a knitted fabric rather than a textured appearance more generally.

The judge agreed with the claimant, noting that certain aspects of the patterning of the lines were inconsistent with a woven fabric or unprinted animal hide such as nubuck or suede. The lines were therefore held to indicate a knitted fabric (such as that present in the “Pointy Flat” shoe), rather than any of the alternative textures suggested by the defendant.

The judge went on to find that, whilst knitted fabrics were known for shoe uppers on gym shoes and sneakers, the notional informed user would not be aware that they had been applied to the types of shoe in question. The use of a knitted fabric on such a shoe would thus stand out to the informed user as a significant departure from existing designs.

As such, the judge decided that the “Allegra K” and “Bonnibel” suede shoes of the prior art would produce a different overall impression on the informed user than the knitted shoe of the RCD. For this reason, the RCD was found to be valid.

Similarly, the judge decided that the knitted shoe of the RCD would produce the same overall impression on the informed user as Giesswein’s knitted “Pointy Flat” shoe. Giesswein’s “Pointy Flat” shoe was therefore found to infringe the RCD.

The Unregistered Community Design

For similar reasons, it was decided that the UCD subsisting in Rothy’s own knitted “Pointed Loafer” shoe produced the same overall impression on the informed user as Giesswein’s knitted “Pointy Flat” shoe, and a different overall impression than the suede shoes of the prior art.

However, on the question of whether Giesswein’s “Pointy Flat” shoe was copied from Rothy’s “Pointed Loafer” – an essential criterion for establishing infringement of the UCD – the judge decided that the designers of Giesswein’s shoe had sufficiently explained how the shoe was independently designed. Therefore, Rothy’s UCD was found to be valid but not infringed.

Practical guidance

Rothy’s succeeded in their registered design claim due to their carefully prepared design drawings, which effectively gave them IP protection over the material and texture of their shoes.

This decision serves as a reminder, further to PMS International Group Plc v Magmatic Limited (i.e. the “Trunki” case), as to the importance of the drawings of a registered design. Care should be taken in the preparation of suitable drawings for a registered design application so as to optimise the scope of protection provided. Creative design drawings should also be considered to protect important features. This decision also shows that that a Court may ‘zoom in’ to design drawings to look at subtle details – emphasising the importance of high-resolution images showing such details.

Lastly, while this decision relates to the infringement and validity of Community (EU) registered and unregistered designs (which, following the end of the Brexit transition period, would no longer extend to the UK), it is still relevant under UK practice (as are other decisions relating to EU design law). This because the UK legal provisions governing the infringement and validity of UK registered and unregistered designs are very similar to those that related to EU registered and unregistered designs.

This article was originally published in Intellectual Property Magazine in March 2021.

Women throughout history continue to make their mark creating innovations and discoveries that impact our lives today. To celebrate International Women’s Day 2021, we reflect on inspiring female inventors in each decade since 1910 – when Mathys & Squire was first founded – to demonstrate the significant value that realising new ideas and inventions can bring.

1910s

- 1914: Florence Parpart

Parpart invented and filed a patent for the first modern electric refrigerator, which she initially marketed and sold to companies in America. The refrigerator represented a revolution for conserving food and is today an integral appliance in any kitchen.

1920s

- 1921: Ida Hyde

Hyde created one of the earliest models of an intracellular micropipette electrode, which can be used to stimulate and monitor individual cells. This technology is still widely used in science laboratories today.

1930s

- 1935: Katharine Blodgett

An American physicist and chemist, Blodgett is known for her work on surface chemistry and invented a revolutionary ‘invisible’, or non-reflective, glass coating, which is used in making camera lenses, microscopes and eyeglasses.

1940s

- 1941: Hedy LaMarr

Although primarily an actress, during World War II LaMarr created a frequency-hopping communication system, which could guide torpedoes without being detected. Her work paved the way for the introduction of Wi-Fi, GPS and Bluetooth to the modern world.

1950s

- 1957: Gertrude Belle Elion

Elion helped to develop numerous life-saving drugs for the treatment of diseases such as malaria, herpes, cancer and AIDS. Along with George Herbert Hitchings, she invented the first immunosuppressive drug, Azathioprine which was initially used for chemotherapy patients, and eventually for organ transplants. She was awarded the 1988 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine.

1960s

- 1965: Stephanie Kwolek

In 1965, Kwolek discovered that polyamide molecules can be manipulated at low temperatures to form incredibly strong and stiff materials, which is used to make Kevlar®. Originally Kevlar® was used to create lightweight, strong tyres for vehicles, but today is best known for body armour, such as bulletproof vests.

1970s

- 1971: Evelyn Berezin

An American computer designer, Berezin created the world’s first computerised word processor and founded her own company to bring her inventions to market. The first model was the size of a small refrigerator. She also developed computer-controlled systems for airline reservations.

1980s

- 1984: Rachel Zimmerman

At the age of just 12, Zimmerman invented a device called the ‘Blissymbol Printer’ that allowed people with speech disabilities to communicate non-verbally – using symbols on a touchpad translated to written language. Her invention has been recognised globally and she has received several awards for her achievements.

1990s

- 1991: Ann Tsukamoto

Tsukamoto is an inventor and stem cell researcher who made a significant breakthrough in cancer research. She co-patented a process for identifying and isolating human stem cells found in bone marrow, which is today used to treat blood cancer, saving hundreds of thousands of lives.

2000s

- 2009: Pratibha Gai

Gai created the in-situ atomic-resolution environmental transmission electron microscope (ETEM), which allows for visualisation of chemical reactions at the atomic scale. Her invention has been used worldwide by microscope manufacturers, chemical companies and researchers.

2010s

- 2012: Deepika Kurup

Kurup is a clean water advocate and as a teenager, after seeing children in India drinking dirty water, she invented a water purification system (photocatalytic composite material) that removes 100% of faecal coliform bacteria from contaminated water using solar energy.

2020s

- 2020: Sarah Gilbert & Catherine Green

Gilbert & Green are two of the leading scientists behind the Oxford/Astra Zeneca Coronavirus vaccine developed in record time amidst the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, saving lives and bringing hope to the entire world.

The inventors listed above are just a small selection of the vast number of women who have developed and, in some instances, patented innovative products that revolutionise the world we live in. At Mathys & Squire, we are privileged to work with innovators across a range of highly dynamic sectors and celebrate their significant technical contributions not just on International Women’s Day, but every day.

World Trademark Review has featured Mathys & Squire in its latest edition of the WTR 1000 directory, highlighting the firm’s “professional, responsive and wide-ranging service” and its ‘unimpeachable record in protecting and enforcing the cornerstone brands of top UK and international companies’. Trade mark partners Margaret Arnott and Gary Johnston have also maintained their statuses as recommended individuals in the 2021 directory.

Now in its eleventh year, the WTR 1000 shines a spotlight on the firms and individuals that are deemed outstanding in this critical area of trade mark practice. The WTR 1000 remains the only standalone publication to recommend individual practitioners and their firms exclusively in the trade mark field, and identifies the leading players in over 80 key jurisdictions globally. Mathys & Squire has been recommended for its outstanding work in the trade mark field, specifically in the ‘United Kingdom: England’ jurisdiction, under the ‘Firms: trade mark attorneys’ category.

In this latest edition, published on 15 February 2021, partners Margaret Arnott (recommended in the categories of ‘Enforcement & Litigation’ and ‘Prosecution & Strategy’), and Gary Johnston (recommended in the category of ‘Prosecution & Strategy’), who co-head the Mathys & Squire trade mark team, have received the following feedback:

For more information and to see the full WTR 1000 rankings, please click here.

In a number of recent cases, patent offices have refused to allow artificial intelligence and machine learning systems to be credited as inventors in patent applications. How are patent systems to respond to the advent of potentially omniscient artificial intelligence (AI)?

In this article for The AI Journal, Mathys & Squire partners Sean Leach and Jeremy Smith consider what impact this might have on the law of invention.

The basis of the patent system is that in return for explaining to the world how to make their invention, an inventor is rewarded with a limited monopoly subject to certain requirements. Firstly, the protected innovation must meet an ‘inventiveness’ criteria and, secondly, the innovation must be described in sufficient detail to ‘enable’ a notional skilled person to make the invention. This is to allow others to learn from the inventor’s contribution so as to foster further creativity and discourage secrecy.

In this context, AI presents a thorny problem. If an AI makes an invention, should that AI be named as the inventor? If so, should the AI be sole inventor? These questions might all seem academic, but they raise a significant public policy question: how are inventors and businesses to be rewarded fairly for sharing their innovations?

The question of inventorship: If an AI makes an invention, should that AI be named as the inventor?

Sean: No. The AI is not a person; it does not have legal personality, and never could. People have drawn parallels to the animal rights questions raised when PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) attempted to have a monkey named as the owner of copyright in a selfie it took with a stolen camera. That is an irrelevant distraction. AI can never have legal personality, not only because it is not an ‘intelligence’ in the human sense of that word, but also because it is not possible to identify a specific AI in any meaningful sense. Even assuming the program code for the AI was to be specified, is the ‘inventor’ one particular ‘instantiation’ of that code? Or is any instantiation the inventor? If two instances exist, which is the inventor? The answer to this question matters crucially in patent law because ownership of an invention depends on it.

Jeremy: It may be true that, in the current patent system, an AI has no legal personality and cannot, therefore, be named as inventor. However, that does not mean that the patent system should not be adapted to require an AI contributor to be named in some way – whether as an ‘inventor’ or as something else (e.g. ‘AI contributor’). There may be policy reasons why patent applications relating to AI generated inventions should be made easily identifiable to public. Such patent applications could, for example, incentivise more investment in AIs because the naming of the AI would act as a showcase for an AI’s capability and could be used by the AI’s creators as part of a ‘royalty-per-patent’ business model. At the same time, naming the AI offers the public greater transparency in relation to how inventions are generated and provides a convenient way to track the potentially increasing contribution made by AIs to providing innovative solutions to the problems faced by mankind.

As to the practical question of how AIs should be identified, there are ways this could be formalised – for example by referring to an entry in an official register of creative AIs that an AI would have to be present on for it to be named as an inventor.

Should the AI be sole inventor?

Our shared view is that a human inventor can – and indeed must – always be named. It is through inventorship that the right of ownership is ultimately determined.

The real question is who, whether aided by AI or not, conceived the solution to the technical problem underlying the invention? For example, if an AI is created with the sole purpose of generating an invention to solve a particular problem, then a creator of that AI is probably also an inventor both of the AI generated invention and the AI itself. If someone identifies a problem to be solved and recognises that a commercially available AI can be used to generate a solution to that problem, then that person could also be the inventor of the resulting AI generated invention. This is not different to the situation in which a software design package is used as a tool of the inventive engineer’s trade.

If an AI is set to work within much broader parameters the inventor might be the person who: identifies the required technical inputs for the AI; identifies the best sort of training data and how best to train the AI to solve the problem; or recognises that the output of the AI solves a particular problem.

These questions may seem speculative and somewhat academic, but we believe the answers to these questions genuinely matter in practice. One of the aims of the patent system is to balance the requirements of: allowing innovators to obtain a just reward for their work; ensuring that protection is granted for innovations that are worthy; and encouraging the innovators make their innovation public. As AI technology is increasingly used as part of the innovation process and, at the same time, the AI industry becomes a more significant contributor to the economy, the patent system needs to adapt to ensure that it encourages, rather than stifles, the use of AI in the innovation process.

This article was originally published in The AI Journal in February 2021.

10 February 2021: This article has been updated to reflect our understanding that the Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.02 has made a referral to the Enlarged Board about the legality of holding Oral Proceedings by videoconference without the consent of all parties. The wording of the referred question(s) has not yet been made public.

The EPO has long offered the option of holding Examining Division Oral Proceedings via videoconference, well before the disruptions caused by Covid-19 this year. As a firm, Mathys & Squire has embraced the use of videoconference for Examining Division oral proceedings for many years now and have bespoke videoconference rooms in a number of our offices that are frequently in use.

In our experience, videoconference oral proceedings before the Examining Divisions – of which the firm has held over 250 to date – work well. We have found them to be well suited to a discussion of the technical and legal issues at hand, and a clear dialogue can be conducted between the presenting attorney and members of the EPO. Not only does the use of videoconference have clear environmental benefits in that it reduces the need for air travel, but it also allows an attorney to prepare and present from their preferred location and removes unnecessary distractions.

With the advent of Covid-19, in April 2020 the EPO decided that all Examining Division hearings would be held by videoconference unless there were “serious reasons” not to. Videoconferencing was also offered for hearings before the Opposition Division, provided there was “the agreement of all parties”.

For Examining Division hearings, this was generally widely welcomed in the profession and allowed the prosecution of patent applications to continue despite the restrictions imposed by Covid-19. Having attended many Examining Division hearings by videoconference from home under lockdown restrictions, the authors of this article have personally found the process to be reliable, clear and convenient. Equally, the process appears to have been convenient for EPO Examiners too, allowing them to attend virtually from different locations.

Opposition proceedings

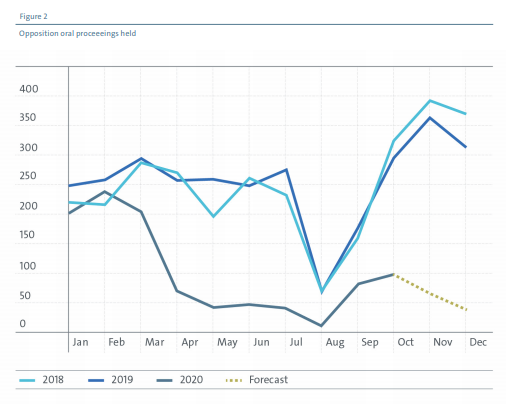

For Opposition proceedings, however, uptake has been low – a progress report published by the EPO noted that the cumulative number of videoconference opposition hearings between May and October 2020 was less than 250, far less than the normal of approximately 250 a month in 2018 and 2019.

This may reflect the greater level of discomfort felt by parties when it comes to relying on a virtual hearing in cases which are contentious (and, hence, more valuable). It might also explain why the largest increase in opposition ‘backlog’ is in the healthcare, biotech and chemistry sector, which has seen a 24% increase in the 12 months to September 2020, versus 15% in mobility and mechatronics and only 7% in information and communications technology.

Faced with this lack of uptake, and to prevent an insurmountable backlog developing, the EPO recently issued a notice (dated 10 November 2020) indicating that as of 4 January 2021 all oral proceedings before both Examination and Opposition Divisions would be held via videoconference, and that videoconference oral proceedings could only be postponed for “serious reasons” and if this was the case they would be postponed until after 15 September 2021. The definition of “serious reasons” is not clear, but an EPO notice indicates that one example of a “serious reason” is where “the demonstration or inspection of an object where the haptic features are essential”. The notice makes clear that “sweeping objections against the reliability of videoconferencing technology or the non-availability of videoconferencing equipment will, as a rule, not qualify as serious reasons in this regard”.

Opposition Division hearings are public, and many of the clients we work with would be interested in attending opposition division oral proceedings, but due to cost and/or travel commitments cannot attend in person. The move to switching Opposition Division hearings to videoconference will allow clients to dial in and watch the proceedings in real-time, thus improving access to justice.

Appeal proceedings

With the switch to videoconference oral proceedings for both Examination and Opposition proceedings, the EPO Boards of Appeal have also been conducting some oral proceedings via videoconference where there is agreement with the parties concerned. The Boards of Appeal confirmed in May 2020 that a videoconference is permissible for an appeal hearing (T 1378/16). From May to October 2020, over 120 appeal hearings have been heard via videoconference; although this is, as for opposition hearings, much less than the total number which would be expected over the same period.

The EPO Boards of Appeal now propose to formalise this change in practice by amending the Rules of Procedure of the Boards of Appeal (RPBA). Following a recent consultation, the Boards intend to add a new Article 15a to the RPBA which would allow the Boards to schedule hearings by videoconference, whether or not the parties to proceedings agree to this. The changes will likely come into effect in April 2021, but the guidance from the EPO suggests that the Boards will start to adapt their practice from January 2021. We therefore expect to see the Boards scheduling hearings by videoconference of their own motion starting early in 2021.

In the consultation on the changes to the RPBA, concerns were expressed in some quarters about a Board insisting on a videoconference hearing if not all parties to proceedings agree to do this. We understand that a question has now been referred to the Enlarged Board of Appeal in case T1807/15 to clarify the extent of the Boards’ powers in this regard. The wording of the question is not yet known.

During 2020, the videoconference facilities at the Boards of Appeal have primarily been set up towards all parties attending remotely (T 492/18 at reason 2.4). However, the possibility of hybrid oral proceedings, in which some parties attend in person and others attend remotely, is permitted under the proposed new Article 15a. In our experience, some Boards have been resistant to hybrid oral proceedings, and it remains to be seen whether the Boards really make use of this option.

The authors have experience of conducting appeal proceedings by videoconference and have found it to be both convenient and reliable.

With bespoke videoconference facilities in our offices throughout the UK, and with an office in Munich, we are well placed to handle both videoconference oral proceedings and also in-person hearings, whether these take place in front of the Examining and Opposition Divisions, or the Boards of Appeal.