In this article for Intellectual Property Magazine, Mathys & Squire partner Juliet Redhouse and technical assistant Angela Stephen examine the different strategies for lengthening patent coverage at the European Patent Office (EPO).

It can be difficult to balance the need to file patent applications early on during drug product development and the length of time it takes to obtain regulatory approval. As patent term is calculated from the date of filing, much of the 20-year patent term has already passed by the time the drug product gets to market. A successful patent strategy needs to extend well beyond the time taken for regulatory approval. This article explores the patent strategies that can assist in extending protection around the drug product.

Patentable aspects of drug development

In addition to the drug product itself, separate patent protection may be obtained for secondary aspects including therapeutic indications, the drug product formulation, methods of manufacturing the drug product and drug combinations. These categories are discussed below, along with examples of what a claim under each category might look like when presented to the EPO.

The drug product

Antibody X against target Y, comprising heavy chain CDRs1-3 of SEQ ID NOs: 1-3 and light chain CDRs1-3 of SEQ ID NOs: 4-6, respectively

For new drug products, the initial patent application will be directed to the drug product itself. Typically, the drug product will be defined by its structure. For example, a chemical compound may be defined by a Markush structure or a specific chemical formula, and an antibody may be defined by the six CDR sequences that are required for binding. At the EPO, there can be some flexibility as to what level of structural definition is required. For example, in the field of antibodies, an antibody may be defined solely by a functional property such as its target epitope, if it is shown that the prior art antibodies do not possess this functional property.

Therapeutic indications

Product X for use in the treatment of breast cancer

It may be possible to obtain separate patent protection for a therapeutic indication following the initial drug product application. However, this can be difficult because treatment of the therapeutic indication with related drug products may already be known and/or data relating to the therapeutic indication may have been included in the initial drug product patent application to support inventive step. A later patent application for the therapeutic indication of the drug should ideally be filed before the drug product patent application is published, so that the latter application is not citable at the EPO as prior art for lack of inventive step.

Product X for use in the therapy of breast cancer, wherein product X is administered at a dose of 0.5-1.0 mg/day

It is well established at the EPO that more specific aspects of a known therapeutic indication may be protected. For example, the particular dosage regimen of a known drug product for a known therapeutic indication may be patentable. In practice, demonstrating an inventive step can be a significant hurdle for dosage regimens at the EPO because determination of the dosage that yields the best effect when the effect as such is already known is considered to be routine. A dosage regimen may, however, be patentable if the prior art teaches away from using the claimed regimen.

Product X for use in the treatment of breast cancer in patients carrying the ABC variant of XYZ gene

In certain circumstances the EPO considers the treatment of a particular patient subgroup with the drug product to be novel over the prior treatment of a broader patient group with the drug product, and the treatment of the specific patient subgroup may therefore be the subject of a later patent application.

Product X for use in the treatment of leukaemia

A later patent application for a new therapeutic indication may be warranted if there is data available supporting that treatment of the new indication with the drug product.

Formulations and crystalline forms

A pharmaceutical composition comprising 2.0 to 5.0 wt % product X, 5.0 to 10.0 wt % excipient Y and the remainder up to 100 wt % water

A patent to the commercial formulation of the drug product can provide another layer of protection. The technical effect of a particular formulation may be related to improved stability or may solve a problem such as low solubility. The scope of protection is likely to be narrow, with the claims limited to the particular drug product. In the case of antibodies, this is often the full sequence of the antibody. The concentrations of the drug product and the components of the formulations are also typically required, often within narrow ranges of the exemplified compositions in the patent application.

A crystalline form of product X having an x-ray powder diffraction pattern comprising peaks at 7.9°, 9.8° and 13.2° ±0.2° 2theta as measured by x-ray powder diffraction using an x-ray wavelength of 1.5406 Å

Patents can also be directed to particular crystalline forms of a drug product, generally defined by reference to peaks in its x-ray power diffraction pattern. In such cases, it is important that a method for obtaining the claimed crystalline form that does not require the use of seed crystal is described in the patent application. The EPO does not accept arguments that crystalline forms are inherently unpredictable and therefore non-obvious, and therefore evidence that the claimed crystalline form is associated with a surprising advantage over the prior art is also crucial. In this respect, evidence of improved filterability and drying characteristics of the amorphous form of a drug substance is not generally accepted, because the EPO considers these to be expected advantages of crystalline forms.

Method of manufacture

A method of purifying monoclonal antibody Y, comprising the steps of…

There may be patentable aspects to manufacturing the drug product, for example to overcome difficulties in large-scale production, or achieving a high level of purity. As for formulations, such improvements are often considered by the EPO to be tied to the particular drug product. The patent examiner may also require very specific details of the method in the claim, unless it can be shown that they are not required for achieving the effect. For example, if an improved purity has been shown using a particular wash buffer composition, this may be required in the claim unless this improved purity is demonstrated using a different wash buffer.

Therapeutic combinations

Composition comprising product X and product Z for use in the treatment of breast cancer

Patents for new combinations of two or more active ingredients can provide useful protection when patent protection for the single active ingredients has expired. To satisfy inventive step at the EPO, synergism of the combination greater than the additive effect of the single active ingredients needs to be shown.

Patent filing strategy

The main factors that influence patent filing strategy are the availability of supporting data and the timing of upcoming disclosures.

Data

A guiding principle at the EPO is that if a technical effect is relied on for the patentability of the claimed subject matter, such as improved binding affinity of the drug product, or improved stability of the formulation, this technical effect must have been made plausible at the filing date of the patent application. If the technical effect of the claimed invention is not rendered plausible in the patent application, then it is unlikely to be taken into account and this will increase the likelihood of the invention being found to lack an inventive step, or lack enablement if the technical effect is stated in the claim. If the technical effect of the claimed subject matter is plausible at the filing date, post-filed data may be filed to support an inventive step. However, plausibility cannot be shown solely by post-filed data.

The nature and amount of data required to demonstrate plausibility will depend on the technical effect being asserted and the scope of the claim. The EPO has been clear that any kind of experimental data for showing plausibility is acceptable, and that in vivo or clinical trial data are not necessarily required. For example, for therapeutic indications, in vitro data is accepted if the observed effect directly and ambiguously reflects the therapeutic indication. In some cases, it may be possible to rely on data that is available in the prior art to demonstrate plausibility.

Comparative data will often be key for arguing an inventive step over the prior art. In particular, patent applications to the drug product formulation should include comparative data over a standard or prior art formulation, and patent applications to the manufacture of the drug product should include comparative data to a standard or prior art protocol. Data showing flexibility on various method steps or formulation components is also desirable, to support breadth for these features in the claim. Comparative data is also important for protecting crystalline forms, to show an unexpected advantage over the prior art forms of the drug product.

Disclosures

A patent application will need to be filed before a public disclosure so that it is novel over that disclosure. Disclosures may be in any form, including conference presentations, journal publications, clinical trial protocols and interim clinical trial results. Clearly, a good publication review system needs to be in place so that the patent attorney is aware of any upcoming disclosures by the technical teams. However, even when there are no planned public disclosures, it can be difficult to keep control of disclosures and maintain confidentiality, and this in particular can apply to clinical trials. It could therefore be appropriate in some cases to file patent applications at several stages of the clinical trial process to try to mitigate this issue.

If there are no planned disclosures, one option might be to retain the knowledge within the company as a trade secret. This could be appropriate for the optimized manufacturing process of the drug product, for example. However, again, it can be difficult to keep control over the disclosures, and the merits of filing a patent application to the manufacturing process should be considered.

Supplementary protection certificates

Supplementary protection certificates (SPCs) are a form of extended protection in Europe for patented pharmaceutical products and agrochemicals after patent expiry. They are designed to compensate for up to five years of patent term that is lost while the product is going through regulatory approval. While a detailed review of SPCs is beyond the scope of this article, as only one SPC can be granted to each patent holder for a particular authorised product, strategic considerations on which patent to nominate for SPC protection, including the strength and scope of the patent, the potential expiry date of the SPC, and the eligibility of the patent for SPC protection, should be borne in mind.

Conclusion

The availability of patents for different aspects of a drug product can extend the patent protection of a drug product beyond the 20-year term provided by the initial product patent. Although the scope of protection generally reduces for the later, more specific patent filings, these patents can still confer meaningful protection of the drug product and provide a barrier to third parties. The precise patent filing strategy will depend on the particular circumstances of each case, including when data will be available to include in the application to support the plausibility of any technical effect that will be important for patentability, and the content and timing of any expected public disclosures.

This article was originally published in the June 2021 edition of Intellectual Property Magazine.

European patents can be opposed by ‘any person’ within nine months of the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent in the European Patent Bulletin. The phrase ‘any person’ includes anyone other than the patent proprietor themselves (G 3/93, G 3/97). Even a person listed as an inventor on a particular patent can oppose that patent (T 3/06).

In a recent appeal at the European Patent Office (EPO) (T 1839/18), the patent proprietor argued that the opponent did not have a legitimate interest in the outcome of the opposition and, therefore, the opposition should be found inadmissible. However, the EPO reaffirmed the principle of ‘any person’ oppositions, stating in the decision, among other things, that any person who starts opposition proceedings provides three main contributions to society at large:

(1) Undeserved monopolies may be revoked or limited to their due scope;

(2) industrial development is fostered in that the direction of innovation is not led astray by wrongfully granted monopolies; and

(3) legal certainty is enhanced.

Given that the opponent can be ‘any person’, this allows potential opponents to hide their true identity by filing the opposition as a ‘straw man’. Filing an opposition as a ‘straw man’ can have a number of advantages and disadvantages.

‘Straw man’ opposition advantages

A potential opponent may wish to avoid alerting the patent proprietor to their interest in the patent potential infringement – for example, the potential opponent may wish to avoid bringing their activities to the attention of the proprietor.

Another reason may be to avoid upsetting an amicable relationship with the proprietor – for example, the potential opponent may be a business partner of the patent proprietor or even a licensee of one or more of the proprietor’s patents.

Additionally, a potential opponent may wish to avoid submitting publicly available arguments regarding, for example, particular interpretations of the patent. In this way, a potential opponent may avoid issues arising from prosecution history estoppel because the arguments filed in the opposition would not be attributed to the company behind the ‘straw man’.

‘Straw man’ opposition disadvantages

In one example, a ‘straw man’ opponent requested the opposition proceedings to be accelerated to provide certainty regarding the fate of the opposed patent before the company behind the ‘straw man’ invested large sums of money into an area which potentially infringed the patent claims. The request for acceleration was denied because the ‘straw man’ opponent did not itself have a legitimate interest in the proceedings being dealt with rapidly. As the company behind the ‘straw man’ was not a party to the proceedings, there was found to be no reason why the interests of a third party should be attributed to the ‘straw man’ (T 0872/13).

It appears in this case that the need for accelerated proceedings was greater than the need for anonymity for the company behind the ‘straw man’. If this had been determined before filing the opposition, then the opposition could have been filed in the name of the ‘true opponent’ which would likely have led to the request for acceleration to be allowed.

In another example, a ‘straw man’ opponent filed experimental evidence which allegedly showed that the patent in suit was not sufficiently disclosed. However, the provenance of this evidence was not provided, presumably because it would reveal the company behind the ‘straw man’, and as such the veracity of the evidence could not be assessed (T 0103/15).

This situation might have been avoided, if before the opposition was filed, the opponent identified that experimental evidence was likely needed to have the patent revoked or limited. Then, the opponent could have arranged for the experiments to be conducted by an independent third party whose identity could have been provided without exposing the identity of the company behind the ‘straw man’.

Conclusion

From the above review, it is clear that oppositions filed under a ‘straw man’ can be beneficial to a potential opponent’s business strategy, but that poor planning of the opposition can lead to unintended negative consequences for the opponent. Therefore, whilst it is certainly worth considering filing an opposition as a ‘straw man’ to obtain the advantages above, care should be taken to identify any potential pitfalls ahead of time to allow appropriate action to be taken to avoid the disadvantages.

Mathys & Squire is pleased to congratulate two of its clients – electric vehicle technology firm, BorgWarner Gateshead and battery manufacturer, Hyperdrive Innovation – following their recent acquisition by Silicon Valley-based company Turntide Technologies.

Backed by Amazon’s Climate Pledge Fund, Bill Gates and Robert Downey Jr, Turntide Technologies develops sustainability technologies that drive down energy consumption and operating costs in buildings, agriculture, and electric transport. The company has confirmed multi-year £100 million investment into BorgWarner and Hyperdrive – both based in the North East of the UK – helping to put the region at the forefront of the UK’s electric vehicle revolution.

Alongside the acquisition, Turntide Technologies has announced the launch of its new UK arm, Turntide Transport, a division focused on modernising intelligent motor systems throughout the commercial transportation industry.

Mathys & Squire has worked closely with BorgWarner and Hyperdrive for a number of years, supporting their IP strategies as both firms have rapidly grown and developed. We are delighted to hear news of this exciting next step and extend our congratulations to both companies, which – through their innovative work and tenacity – are leading the way in the electric vehicle sector.

A new partnership between Mathys & Squire Consulting and deep tech communications firm, Inkvine, has launched today to foster innovation and IP commercialisation and valuation in the technology sector. The partnership will provide client portfolios of both firms with access to the extensive domain expertise of the other, extending collective services to provide client support for long-term IP and market proposition.

Mathys & Squire Consulting – formerly known as Coller IP – is a wholly owned subsidiary of leading European patent and trade mark attorney firm, Mathys & Squire LLP. Together with its parent firm, Mathys & Squire Consulting specialises in providing independent advice and services across all legal and commercial aspects of IP, including due diligence, audits, valuation, training, innovation landscaping licensing, monetisation and competitive intelligence.

Inkvine helps breakout technology firms find their voice and capture emerging markets. Founded by Emily Ross in 2016, the company defines and executes complete go-to-market strategies – from positioning and core communications, to channel and funnel optimisation. Armed with a deep understanding of emerging technologies and backed by a distributed team of technology experts, Inkvine has helped a range of startups, foundations, and platforms cross the chasm from ideation to measurable growth.

Inkvine founder and CEO, Emily Ross, commented: “Intellectual property is such an important area for the companies we work with. Often they push the boundaries of technical capability and innovation and it’s critical that they have expert guidance through the complexities of IP, patents and trademarks, because it makes such a difference to long-term financial success. We are skilled at building brands and communicating remarkability, and IP is a significant part of the communications mix. Having IP expertise to draw on gives our customers clear commercial advantage.”

The two will be collaborating jointly on a number of innovation projects over 2021 and 2022, with the first project scheduled to launch in Q4.

The value of a business’s intangible assets and intellectual property (IP) is key to its ability to support revenues through sales of products/services, franchising, licensing, or through attracting investment and fundraising activities.

However, the value of intangible assets is also relevant when a business goes into administration or liquidation due to insolvency. In both instances, where the business is restructured or its assets are liquidated to satisfy the creditors of the business, the intangible assets can retain a significant amount of value. In the context of the intangible/IP assets adding value to the business, these may include patents, trade marks, registered designs, copyright, trade secrets or databases, and nowadays even software assets. All these assets may also be supported by additional know-how and R&D information held by the business.

In the event of insolvency, the value of these assets is examined in the context of their use by the business, with appropriate discounting for the fact that that they are to be sold in a liquidation. In a pre-pack administration procedure, where the business is still viable, the existing value of the intangible assets may be easier to retain.

The Mathys & Squire Consulting team has many years’ experience in valuing intangible and IP assets in such insolvency and administration scenarios, using a variety of methodologies across a variety of asset classes, including: brand assets, patent portfolios, software assets and client databases – across a variety of sectors including: high-tech, fintech, food & beverage, and entertainment. Fixed prices and fast turnarounds are available to meet client requirements.

Furthermore, the Mathys & Squire Consulting team has a network of experts to build a suitably resourced team for larger or more complex projects.

Our typical valuation processes involve:

- identifying the intangible/IP assets to be valued for the purpose of the insolvency;

- understanding the use of the assets in the liquidated business;

- understanding the potential use and applicability of the IP assets in a new business, through acquisition of the entire business or acquisition of the IP assets alone; and

- benchmarking the IP assets against similar assets valued and sold under stressed sale scenarios.

Our team is very happy to arrange an initial free of charge call to discuss your insolvency IP valuation requirements – please get in touch for more information.

Note: Mathys & Squire Consulting formerly traded as Coller IP – more details are available in this press release.

For US patent attorneys seeking patent protection via the European Patent Office (EPO), European amendment practice and so called ‘added matter’ objections can be a real headache. One particular added matter issue arises from so called ‘intermediate generalisation’. This may occur when a feature is isolated from an embodiment and added to a claim without other features of that embodiment.

It is often the case that, in practice, the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) and the English courts approach the question of added matter and intermediate generalisations more flexibly than the EPO. The recent decision of the High Court in Philip Morris v British American Tobacco (BAT) [2021] EWHC 537 (Pat) does not seem to follow this trend.

EPO v UK ‘added matter’ practice

The EPO Guidelines state that it is only permissible to isolate a feature from an embodiment and add it to a claim if:

(i) the feature is not related or inextricably linked to the other features of that embodiment, and;

(ii) the overall disclosure justifies the generalising isolation of the feature and its introduction into the claim.

Although the UK Manual of Patent Practice (see 76.15.5 in link) defines a similar approach to that set out in the EPO guidelines, in practice the application of standards at the UKIPO is less rigid. This might be because the manual explains a number of real-life practical examples of claim amendments which do not find verbatim basis in an application, but which are not to be objected to as added matter. There are also some significant decisions of the English courts which appear to follow a more liberal approach from that which we see applied by the EPO.

The recent Philip Morris v BAT decision

In the High Court judgment Philip Morris v BAT [2021] EWHC 537 (Pat), [4] the patent in suit included a claim which had been amended based on an embodiment.

“A cigarette (150) for use with a powered aerosol generating device (10) comprising … at least one electrical resistance heating unit (72) … and a controller mechanism (50) including a sensor (60) that is capable of selectively powering the electrical resistance heating element (72) at least during periods of draw…”

In attacking validity, Philip Morris argued that this claim added matter because it didn’t recite a puff actuated sensor which, in the application as filed, was functionally related to the electrical resistance heating unit. In the judgment, the judge stated: “It is not enough that the skilled reader would think that they might be, or were likely to be independent, or that the skilled reader would not know, or would not think about it.”

The patentee, BAT, argued that the original application taught that certain features were optional. The judge accepted that the heater and puff actuated sensors were optional in the embodiment seen in Figure 1 and 2. The claim found basis in the embodiment of Figure 3, the description of which referred back to Figure 1 and said that this was “generally comparable”. However, the judge was not convinced that this was a sufficiently clear disclosure of omitting the puff actuated sensor when using the embodiment of Figure 3 as basis to amend the claim, so the amendment was found to add matter by intermediate generalisation.

The UK judge did not explicitly say that he was applying the EPO test, but we believe the EPO test would have led to the same result. We are, however, less sure of agreement between this decision and the guidance set out in the UKIPO’s Manual of Patent Practice.

In November 2020, the Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof – BGH) issued another landmark decision on FRAND in Standard Essential Patent (SEP) disputes in the Sisvel v Haier case. While the result of the decision – i.e. that the BGH would overturn the decision of the OLG Düsseldorf (which went against the first instance decision) – was announced last year, the legal reasoning of the BGH was not published until March 2021.

In summary, the BGH has strengthened the rights of SEP holders by clearly defining and raising the requirements for SEP users’ willingness to license, which must be complied with in the context of the FRAND conditions:

- The user must actively avoid a ‘patent hold out’ and work towards doing everything necessary on his part to reach a licence agreement. This applies in particular to the obligation to respond to an SEP holder’s offers in terms of time and content.

- The BGH particularly emphasised the content-related part of the user’s reaction. Thus, targeted communication is required, e.g. with active participation in the negotiation with the aim of bringing the process to a successful conclusion.

- The active and targeted negotiation participation is not a one-off, but, according to the BGH’s reasoning, an ongoing obligation, especially for the SEP user.

- In the event that a user of an SEP has delayed the negotiations in the course of the negotiations, he may remedy such delay by making additional efforts towards the conclusion of a licence agreement.

In addition to the above clarifications on the requirements for a licensee in the context of an SEP dispute, the BGH also commented on a potential review of FRAND conditions in the amount of the licence fee. It states that there is no single FRAND rate, but depending on the course of the negotiation and the relationship of the negotiating parties, these can lead to different results. A judicial determination of a FRAND licence contradicts the BGH’s understanding that FRAND means that both parties are willing to reach a compromise, whereby this compromise automatically constitutes FRAND.

In summary, the present case law of the BGH further strengthens the position of the SEP holder. In connection with the latest decisions of the regional courts on the assessment of anti-suit injunctions, the court location in Germany for the enforcement of SEPs is further strengthened.

The Queen’s Speech was held yesterday, 11 May 2021, announcing the UK Government’s plans for the year ahead. We were pleased to see that the Government is planning ‘the fastest ever increase in public funding for research and development’, along with plans to pass legislation to establish the new Advanced Research and Invention Agency.

This is not a completely new idea for this Government; research and development (R&D) was a key focus in the Queen’s Speech back in December 2019, when the Government set out its intention to make the UK a ‘global science superpower’ that attracts brilliant people and businesses from across the world and said it would unveil R&D funding plans to accelerate its ambition to bring R&D spending up to 2.4% of GDP by 2027. The Government flagged back then its intention to create a new approach to funding emerging fields of research and technology by providing long term funding to support visionary ‘high-risk, high-pay off’ scientific, engineering, and technology.

£14.9 billion is currently being invested in R&D in 2021-22, meaning UK Government R&D spending is now at its highest level in real terms for four decades. This investment reinforces the Government’s commitment to putting R&D at the heart of plans to build back better from the pandemic, and includes funding for association to Horizon Europe, investing at least £490 million in Innovate UK in 2021-22. The Government has said it will increase public spending on R&D to £22 billion by 2027.

Over the last 18 months or so, the Government has been finessing some of these ideas for investing in R&D, and this high-risk, high-reward approach now has a name: the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA), which, as confirmed in the March 2020 Budget, will receive £800 million of government funding by 2024-25. ARIA is intended to ‘unleash the potential of the UK’s world-class research and science base’ and more details of those plans were announced this week. It will support ground-breaking technology, with the potential to produce transformational benefits to our economy and society, new technologies and new industries. The plan is to provide a similar model to the Advanced Research Projects Agency set up by the US government in 1958, whose investment in research led to the creation of the internet and the Global Positioning System (GPS).

So how will ARIA differ in its approach from the UK R&D funding currently on offer? One of its aims is to tolerate failure in order to allow for very ambitious research. Whilst this may seem odd, the rewards from accepting a higher level of risk compared to traditional public investment could be very high indeed. As IP attorneys working so closely with innovators, we know that it is not possible to simply predict what the next big technology may be; without the opportunity to fund a range of (potentially absurd) ideas, it may never be found.

The ARIA Bill, which is currently at the ‘report stage’ in the House of Commons, also plans to give ARIA a large amount of autonomy and freedoms over its day-to-day affairs in order to achieve this and encourage investment in areas that do not currently receive public funding (perhaps those that are viewed as too odd or too risky). One of the proposals in the Bill is that the Secretary of State will have the power to dissolve ARIA only after 10 years. This makes sense; if the strategy is high-risk, high-reward, there may be many failures before we see anything commercially successful result from this different approach to funding and we will need to give it time before deciding whether this funding approach has a long-term future for the UK.

The intention is that ARIA will help ensure the breakthroughs of the future happen in the UK. We look forward to seeing the exciting research, inventions and technologies that come out of this new agency.

A recent report published by the European Patent Office (EPO) shows that despite the disruption caused by the COVID pandemic, the number of EP applications filed in 2020 remained stable overall, whilst showing growth in healthcare and life sciences.

Overall, 180,250 applications were filed at the EPO in 2020, which was 0.7% down on the 181,532 applications filed in 2019. Whilst this is positive given the substantial disruption in 2020, we suspect that with the delays associated with the Paris Convention and the Patent Cooperation Treaty, the true effect of COVID is unlikely to be seen in Europe for another year or two.

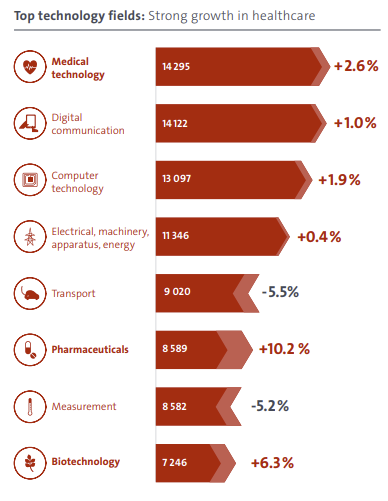

Although the total number of EP applications filed in 2020 was down, filings were up in several technical areas including medical technology, digital communication, computer technology, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology. The graphic below (published by the EPO) shows the change in each technical area.

Given the ageing populations in developed countries around the world, it is perhaps unsurprising that healthcare technologies (including medical technology, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology) have increased.

Similarly, given the significant investment in computer and telecoms technologies by Chinese and South Korean firms, it is unsurprising that digital communication and computer technology were also up – a trend that is likely to continue in the years ahead, given the public’s insatiable desire for greater and faster data transfer for smartphones and tablet devices.

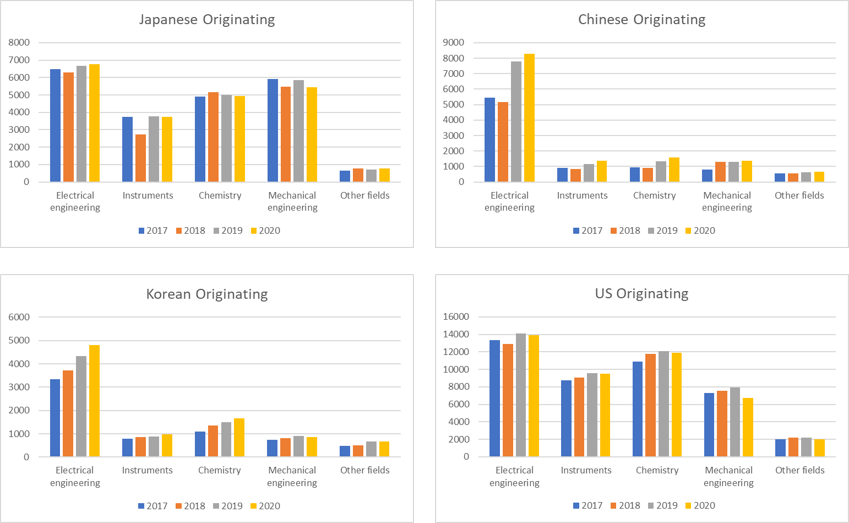

Further analysis of the EPO data reveals some interesting filing trends for applicants based in different countries; the tables below show the filing activity for applicants based in Japan, China, South Korea and the US.

As is evident from these graphs, filings from applicants based in Japan and the US were down overall, whilst for applicants based in South Korea and China, the filings were up in nearly all technical fields. Indeed, the number of cases filed by Chinese applicants in the general ‘electrical engineering’ field has now surpassed those filed in the same field by Japanese companies. At this rate of increase, it won’t be long before Chinese applicants are filing more EP applications than US-based applicants in this technical field.

The rate of filing by Chinese companies in this area clearly demonstrates China’s desire to dominate and control digital technologies (such as IoT and 5G) that will underpin the next technology revolution. Given the importance of these technologies to the future economic prosperity of all countries, it is perhaps unsurprising there is significant political unease in the West with Chinese dominance in this area.

It is clear for anyone watching the energy space, that hydrogen and electric vehicles (EVs) are two areas of significant investment and innovation in recent years, the two forming part of significant global efforts towards decarbonisation of the automotive sector.

In late 2020, German luxury car manufacturer, and part of the Volkswagen Group, Porsche, announced significant investments in electromobility. As a producer of high-performance, high-cost and long lasting vehicles, and under pressure internationally to reduce fossil fuel emissions and environmental performance, the company has announced its investment in the eFuels project, of which it will be one of the principal customers. The project, which is part of the Highly Innovative Fuels (HIF) Project is the product of a partnership between Porsche, Siemens Energy, AME, Enel and Chilean company Enap to produce e-fuels with the aid of wind power at the Haru Oni site in southern Chile. In this context, Porsche has invested €24m and the German Government has invested €9m.

The eFuel technology essentially uses electrolyser produced hydrogen, powered by wind energy, which is combined with atmospheric CO2 to produce methanol. This is in turn converted into a pure gasoline based on licensed Methanol-to-Gasoline (MTG) technology from Exxon Mobil. This green gasoline does not contain sulphur and is produced using sustainable energy sources. The eFuel concept represents an interesting collaborative approach from industry to supply Porsche and its customers with a greener fuel, through use of technology and expertise from a number of companies, while not necessitating engine modifications typically required where methanol is itself used as the automotive fuel. At the same time, Porsche, and its parent Volkswagen, have recently announced plans to open an EV battery cell factory in Tübingen in the southern state of Baden Württemberg, not far from HQ in Stuttgart. This move by Porsche essentially represents a two-pronged approach to minimise its emissions, on the one hand electrifying is future fleet and on the other hand using sustainably produced eFuels to reduce the overall emissions of its existing fleet. Its sister firm Bentley has similarly expressed a potential interest in eFuel technology.

While this approach will allow its existing fleet to continue, it is clear that for Porsche and many of its competitors the industry is moving to electrification, with German competitors such as Audi and BMW already selling pure electric vehicles, and with many more in the pipeline. As such, it is fitting that the majority of patent filings in battery technology over the last 10-15 years has related to EV power storage technology, generally focusing on Li-Ion battery technology, although in recent years redox-flow batteries have been increasingly investigated for stationary power storage. In many cases technical innovations on battery-based energy storage can apply equally to EVs as they do to stationary storage systems.

The wider move towards EVs is reflected in the sharp uptick in plug-in EV registrations over the last two years, which in the UK alone has doubled since 2019, from approximately 250,000 in 2019 to 500,000 in March 2021, with battery powered electric vehicles (BEVs) accounting for most of this growth, whilst plug-in hybrid vehicles have seen a smaller growth. This move is further reflected in the overall market share for plug-in EV of new car registrations in the UK, which was approximately 3% in 2019 and has reached almost 15% in early 2021.

In the wider context of battery development and innovation, the focus is very much on Japan and Korea, with large multinational electronics companies such as Samsung, Panasonic, LG Electronics, Sony and Hitachi in pole position. Toyota and Nissan are the most active automotive players. German company Bosch comes in fifth position of overall ranking of patents filed in the battery technology space. EPO reports indicate that this is heavily influenced by the energy policies in both countries. To strengthen the UK’s position in the field of electrochemical energy storage and battery technology, the Faraday Institution was established in 2017 as the UK’s premium research programme on innovations in battery technology, market analysis and early stage commercialisation. Under the auspices of the Faraday Institution, which is a collaboration of over 20 UK universities and 50 industry partners, new innovations are taking place in Li-ion, solid-state, sodium ion and Li-S batteries. The Faraday Institution recognises that EV technology is growing and the take up of electric vehicles in the UK alone is quickly increasing and is expected to reach 60%-70% in 10 years’ time.

According to recent reports, the UK has recently overtaken France as Europe’s second largest EV market after Germany. This trend looks set to continue, and clearly Porsche is not alone amongst the high-end luxury car manufacturers going electric. Lotus has recently announced a £2.5 billion investment in the UK to retrofit its UK factory for the switch to EV, with the firm planning to sell only EVs by 2028. This interest is clearly demonstrated in the patent portfolio of Lotus owner Geely, with many of the most recent patent filings from the Chinese automotive manufacturer relating to EVs and hybrid vehicle control systems, charging and energy storage system, power conversion and thermal management systems. A similar focus is seen across many of its competitors.

Overall, it is evident across the automotive sector that efforts are being made throughout the value chain towards decarbonisation and reduction of environmental impacts, and EVs will form a significant part of this approach.