Last week saw the release of the UK government’s spring statement which announced new tax breaks for IP owners undertaking research and development (R&D) in the AI, quantum computing, cloud computing, and robotics sectors.

This is facilitated by allowing R&D expenditure on pure mathematics to qualify under the R&D tax relief scheme, with the intention of supporting emerging, technology-driven sectors.

The announcement appears to align with the National AI strategy, released in September 2022, which aims to boost AI capabilities in the UK with the culminating goal to ‘make Britain a global AI superpower’. The Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport and the Office for Artificial Intelligence has also projected that more than 1.3 million UK businesses will use AI by 2040, and spending on AI by UK businesses is expected to reach more than £200 billion by the same date, up from £63 billion in 2020.

This is great news for the UK’s many innovative businesses working in the AI, robotics, and quantum tech space. The Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, also raised the possibility of further innovation relief for future green energy-related schemes.

The R&D tax break is in addition to the Patent Box scheme, a tax relief initiative introduced in April 2013 which offers companies reduced tax rates on profits from products and services covered by patents, in order to recognise innovation in business.

For more information, please reach out to a member of our team.

The final version of the Rules on Representation before the UPC has now been published, and we are pleased to confirm that all our UK, French and German attorneys will be able to represent our clients before the new UPC when it is up and running.

The official rules regarding representation rights can be found here.

More information on the UPC and what its advent means for European patent rights holders can be found on our UPC Hub.

Facebook’s rebranding to ‘Meta’ in 2021 brought renewed attention to the metaverse, a shared virtual environment that, at least according to Meta, is the next evolution of social connection. The metaverse offers the potential to radically change many aspects of life, including learning, working and socialising. The metaverse – and the investment flowing into it – provides opportunities for companies looking to innovate and to protect their innovations.

While the introduction of Meta is relatively recent, the development – and patenting – of metaverse technologies has been ongoing for decades. While some companies already have substantial patent portfolios built up in this space, the metaverse is a huge space, so much room remains for innovation and patenting.

Hardware technologies

In principle, seeking patent protection for hardware technologies for the metaverse tends to be quite straightforward – and there are many existing patents for virtual reality and augmented reality headsets. When seeking protection for hardware technologies, the major barrier is likely to be the need for novelty and inventiveness. While this is far from simple in what has become a crowded space, there are of course myriad areas in which metaverse hardware can be improved.

Software technologies

On the other hand, obtaining software patents for metaverse technologies is likely to be comparatively more difficult from a subject matter point of view, but there is still substantial scope to protect such inventions. Much of the metaverse will be built on simulation, either of the real world or virtual locations and situations. As demonstrated in European Patent Office (EPO) decision G1/19, patenting inventions for simulation can be difficult via the EPO (and, indeed, in the UK). However, such restrictive provisions are not universally applicable. Obtaining protection for these types of inventions in, for example, the US can sometimes be more straightforward.

Future of patents in the metaverse

In any event, getting a patent granted for many of the technologies required to implement the metaverse, and especially the simulations within it, is likely to be possible. As an example, much of the recording of information and transactions associated with the metaverse will occur using blockchains or similar technologies – and as explained in our recent article, obtaining protection for these technologies is currently possible in many jurisdictions.

In short, protecting software inventions associated with the metaverse might not always be easy, but there is certainly room for innovation. While care should be taken to position the software inventions in a patent-friendly manner, there is plenty of scope for obtaining protection for all types of metaverse inventions.

UK companies working in the human medicine, medical diagnostics and medical device sectors now have access to a new £60 million fund to support their manufacturing projects and promote growth in the UK’s life sciences sector.

The Life Sciences Innovative Manufacturing Fund (LSIMF) was launched earlier this month by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and the Office for Life Sciences. A significant barrier to the deployment of emerging technologies is the restrictive up-front costs of setting up production, which the LSIMF aims to mitigate by providing capital grants to companies with projects operating in target fields, including pharmaceuticals (such as cell, gene and nucleic acid therapies); disease diagnostics; and medical devices. The first wave of applications is now open, with a deadline of 12pm on 31 March 2022, and further monthly deadlines on 29 April and 31 May 2022 for two subsequent waves.

To be considered eligible for these grants you must be a UK registered company, and the project in question must be a manufacturing project located in the UK within one of the approved sectors. The published guidance also indicates that an eligible project should have a minimum total cost of £12 million (although BEIS reserves the right to approve smaller projects under certain circumstances). Since this is a capital grant fund, certain intangible costs that would form part of this total (such as R&D) will not be eligible for grant funding.

The application process involves a number of stages, including an interview with an expert panel to discuss the project’s alignment with the fund’s objectives, a due diligence report of the application and ministerial assessment.

For full information on this fund and how to apply, click here.

The European Commission has launched a public call for evidence in response to a proposed reform of the supplementary protection certificate (SPC) system. The initiative will put in place “a unitary SPC and/or a single (unified) procedure for granting national SPCs” in an effort to benefit the health sector by making them more accessible and efficient.

Following an evaluation in 2020, the Commission identified that SPCs being granted and administered nationally is the “main shortcoming” of the current system: “SPC applications are currently filed at the national patent office of each EU Member State where protection is sought and in which a basic patent, to be extended, has been granted. This undermines their effectiveness and efficiency.” The initiative is intended to tackle the following key issues:

- Divergent outcomes of the grant procedures across EU countries

- Lack of unitary SPC protection for the future unitary patent

- Suboptimal transparency of SPC-related information

- High cost and administrative burden for SPC users

Further information about the initiative is available to download here. Feedback can be provided until Tuesday 5 April 2022, please click here to have your say.

For more information about SPCs, visit our webpage here.

Applicants seeking patent protection in European markets have two routes available: via the European Patent Office (EPO), which provides a single examination procedure for all EPC contracting states; or the ‘national route’ which involves filing individual national applications in each country where protection is sought. Whilst there are benefits and drawbacks to both, below are some reasons to consider the national route in the UK.

1. The UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) often grants patents more quickly than the EPO

The UK system provides the option to receive a combined search and examination report (CSER) approximately two months after filing. If a reply that addresses any objections raised in the CSER is filed promptly, it is possible for a patent to be granted in around eight months. This is, on average, much faster than EPO timescales. Furthermore, for inventions with environmental benefits, the UK offers a Green Channel which allows applicants to request accelerated processing, resulting in a CSER being issued in just six weeks.

It is also common in the UK for agreement to be reached on allowable claims by telephone call with the examiner, which can substantially accelerate prosecution, without reliance on written formalities. This may be advantageous to keep a short file wrapper, which can be helpful if the patent is ever litigated.

The UK system has a compliance period of four and a half years from the date of filing, meaning all UK applications must be ready for grant beforehand, preventing ongoing prosecution extending over many years. In practice, examiners may review applications that are close to the end of their compliance period more quickly. While this may be helpful for some, it can be disadvantageous for others who favour long pendency and flexibility to file a series of divisional applications.

2. Acceleration in other territories

The UKIPO is well respected and provides a high standard of examination which can provide a basis for accelerating grant in other territories. Under the Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH), granted UK patents can be used to accelerate prosecution in Australia, Canada, Germany, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, and the United States, amongst others.

3. The UKIPO offers very good value for money

Patent application and associated grant costs in the UK can be lower than in many territories. For example, where the EPO may charge £3,000+ for filing an application, requesting search and examination, as well as grant fees, in the UK it could cost just £310. Renewal fees are also far cheaper at UKIPO than at the EPO.

It is relatively rare to be summoned to a hearing at the UKIPO, unless requested or as a last resort, as opposed to the EPO where oral proceedings are reasonably common. Furthermore, the EPO Guidelines (C-III, 5) permit the issuance of a Summons to Oral Proceedings as the first action in examination. As preparation for a hearing is more expensive than written communications, the UK approach can help to keep costs down during prosecution.

If you are only interested in protection in a few European countries, such as the UK, France and Germany, direct filings with the national patent offices can be more cost effective than a European patent application.

Furthermore, registration systems also exist which allow UK patents to be re-registered in a selection of overseas territories including Hong Kong and Gibraltar. Re-registration can provide a cheap and easy way to obtain patent protection elsewhere.

4. UKIPO procedure is less rigid than at the EPO

The UKIPO gives applicants more opportunity to amend claims than the EPO does, and discretionary amendments are rarely not permitted. The UKIPO also provides options to have more than one claim set searched, and there is no deadline on a second search request, giving applicants the opportunity to be more informed about the potential patentability of their invention(s) and their protection strategies, e.g. before a decision is made as to whether or not to file a divisional application.

There is no hard rule on conciseness in the UK, and multiple independent claims in the same category can be accepted in circumstances which may not be allowed by the EPO, which can again help to reduce costs and obtain a broader scope of protection in a single application.

5. The UKIPO’s inventive step standard can, in practice, be less strict than at the EPO

At the UKIPO, the EPO’s ‘problem and solution’ approach does not need to be followed (although it will be accepted) and the UKIPO inventive step approach is less rigid. Arguments based on the relative age of documents and the commercial success of the invention can be given more weight at the UKIPO than at the EPO.

6. Adding credibility to a patent family

The UKIPO is well respected, so having a patent granted in the UK relatively early on acts as a deterrent to potential infringers in other territories who might be considering engaging in infringing activities, as they may expect you to obtain similar patent coverage in other territories.

7. Streamlined enforcement procedures

The UK offers fast track patent litigation in a specialist court with expert judges and commercially reasonable limits on liability for the other side’s legal costs. If enforcement is necessary, the UK’s Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC) offers procedures that resolve certain cases (limited to claims of <£500,000) more quickly than disputes heard in the High Court. The IPEC has been set up to be time- and cost-effective, and ability to resolve disputes in such a way is highly desirable.

8. Reliable judgments and expert judiciary

The UK Patents Court (Chancery Division of the High Court) consists of specialist judges with IP expertise. There are also several highly experienced IP expert judges in the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court, for hearing more complex cases that reach these higher-level courts.

The approach to claim interpretation taken by the European Patent Office (EPO)’s Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.03 in its recent decision T 1127/16 appears to be at odds with the UK Courts’ doctrine of equivalents, as recently applied in Illumina Cambridge Ltd v Latvia MGI Tech SIA & Ors [2021] EWHC 57.

UK Courts’ doctrine of equivalents

In the UK Supreme Court’s decision in Actavis v Eli Lilly [2017] UKSC 48, Lord Neuberger developed a new approach for dealing with “equivalents” in UK patent infringement. The decision set out a two-part approach to assessing whether a UK patent is infringed by a product or process that is an equivalent variant of that claimed in the patent. This approach involves asking the following two questions:

- does the variant infringe any of the claims of the patent as a matter of normal interpretation; and, if not,

- does the variant nonetheless infringe because it varies from the invention in a way or ways which is or are immaterial?

If the answer to either question is ‘yes’, there is an infringement. Otherwise, there is not.

As an extension of the second question, Lord Neuberger set out three further questions (that have come to be known as the ‘Actavis Questions’) for evaluating whether a variant is ‘immaterial’:

- Notwithstanding that it is not within the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent, does the variant achieve substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the invention?

- Would it be obvious to the person skilled in the art, reading the patent at the priority date, but knowing that the variant achieves substantially the same result as the invention, that it does so in substantially the same way as the invention?

- Would such a reader of the patent have concluded that the patentee nonetheless intended that strict compliance with the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent was an essential requirement of the invention?

The third Actavis question – Illumina Cambridge Ltd v Latvia MGI Tech SIA

The High Court of England & Wales applied the doctrine of equivalents principle in its recent decision in Illumina Cambridge Ltd v Latvia MGI Tech SIA, which related to DNA sequencing technology.

One of the patents covered in this decision claimed a process involving ‘incorporation’ of a nucleotide. It was argued that this claim was infringed by the use of another process involving an allegedly equivalent variant of the claimed ‘incorporation’ step.

However, the description of the patent contained a specific definition of the term ‘incorporation’ as referring to “(…) the joining of the nucleotide to the free 3’ hydroxyl group of the nucleic acid strand via formation of a phosphodiester linkage with the 5’ phosphate group of the nucleotide.” The allegedly equivalent incorporation step did not accord with this definition.

Based on this definition, the judge held that “(…) the answer to the third Actavis question should be in [the defendant’s] favour (…). The reason why skilled person would think that strict compliance with the normal construction of ‘incorporation’ was essential is because the specification has gone out of its way to define that term in a clear and simple way. It is not necessary for the skilled person to speculate about why the patentee may have done that, the fact is that it has been done (Paragraph 396)”.

Therefore, in this decision, the description of the patent was used to impart a narrower interpretation of the claims of the patent, such that they were held to exclude the allegedly equivalent variant by virtue of the third Actavis question.

EPO decision T 1127/16

In this decision, the Technical Board of Appeal considered related issues of claim interpretation, taking an approach that appears to be at odds with the approach taken in the Illumina Cambridge decision.

T 1127/16 was an appeal against a decision of the Opposition Division to revoke a European patent on the grounds that the main claim – as interpreted – extended beyond the content of the application as filed. The claim in question related to a method for handling aircraft communications involving communicating with the ground via a plurality of broadcast networks, arranged in an order of preference and stored within a preference list. The method involved evaluating the highest in preference broadcast network and whether it is available, before transmitting a message. Importantly, the claim involved the following features:

- “(…) evaluating a preference to determine a preferred network of the plurality of transmission networks,

- wherein the preference comprises a preference list identifying a selection of the plurality of broadcast networks in order of preference

- and identifying the highest in preference of the plurality of broadcast networks in the preference list that is available.”

One of the main questions of claim interpretation was whether features (b) and (c) should be read in combination or, as argued by the patentee, separately. If read in combination, the claim defined a preference list that identified both a selection of the plurality of broadcast networks in order of preference, and the highest in preference of the plurality of broadcast networks in the preference list that is available. The Opposition Division and Technical Board of Appeal both considered that there was no basis in the application as filed for such a preference list.

It was argued by the patentee during the appeal proceedings that the skilled person would consult the description to resolve this ambiguity, and that the description would clarify that in fact features (b) and (c) should be read separately, rather than together.

However, the Technical Board of Appeal took a different approach, stating that “(…) the description and the drawings of the patent [do not] have to be consulted automatically as soon as an “ambiguous” feature (i.e. a feature which at least theoretically allows more than one interpretation) occurs in the claim, or where the claim as a whole includes one or more inconsistencies, to resolve that ambiguity or inconsistency. According to such a logic, an applicant could then arguably dispense with providing a clear and unambiguous formulation of claim features (…) in order to be able to fall back on a more description-based interpretation at will during a subsequent opposition proceedings.” (Reasons 2.6.1.)

The Board considered there to be no linguistic problem with reading features (b) and (c) together, and that the repeated use of the verb “identifying” in these features, as well as there being no comma separating these features, would lead the skilled person to read these two features together. The Board also considered this interpretation of the claim to be technically credible, setting out an exemplary implementation of the invention according to this interpretation. On this basis, the Board decided that the claim extended beyond the content of the application as filed and thus dismissed the appeal.

The importance of commas?

Finally, much has been written about how the appeal in T 1127/16 failed as a result of the simple omission of comma between claims features (b) and (c), as set out above. The reality is, perhaps reassuringly, more nuanced.

The patentee in T 1127/16 did in fact file an auxiliary request in which a comma wasinserted between features (b) and (c). Considering this request, the Board nonetheless decided that “(…) despite the presence of the comma, the claim may – linguistically and technically – still be given the same meaning as (…) the main request”. (Reasons 3.2.)

Therefore, it is clear from the Board’s reasoning that they considered the presence or absence of comma between features (b) and (c) to be just one factor contributing to the way in which the claim should be interpreted. In practice, this factor was outweighed by others, such as the repeated use of the verb “identifying”, which were of more importance.

Conclusion

The EWHC’s decision in Illumina Cambridge and the EPO Technical Board of Appeal’s decision in T 1127/16 illustrate differing approaches to using the content of the description of a patent to interpret the claims.

In Illumina Cambridge, the EWHC relied on a definition provided in the description to interpret a key feature of the claim. This decision therefore highlights the potentially significant role the description can potentially play in interpreting the claims – particularly in the context of infringement proceedings – and therefore the care that should be taken when drafting the description, particularly with regard to any definitions of claim wording.

In T 1127/16, the Technical Board of Appeal took a more restrictive view of the role of the description in interpreting the claims, indicating that the description need not be consulted automatically, even when the claims are ambiguous when read in isolation. It is unclear how such an approach to claim interpretation would enable one to answer the third Actavis Question, which necessarily requires the claims to be read in the context of the whole patent to understand whether the reader would have concluded that strict compliance with the literal meaning of the claims was an essential requirement of the invention. Nonetheless, this decision serves as reminder as to the importance of drafting claims that are clear and unambiguous, independently from the description, and as to the potential effects of seemingly minor differences in claim wording.

(C) Naomi Korn Associates & Mathys & Squire 2022. Some Rights Reserved. These case studies are licensed for reuse under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike Licence.

This case study reviews the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SMEs (small – medium enterprises) from early 2020 through to 2021. It focuses on the industries most affected by the crisis and whether intellectual property (IP) and IP management may have helped mitigate its impact through adaptation and change. It forms part of a series of case studies from across multiple industries examining the role of IP and IP management during COVID-19 and lessons learnt. It is aimed at governments and SMEs who are planning business recovery strategies involving IP assets, over the coming months.

Sector overview

The catering and wider food & beverage (F&B) industry worldwide predominantly comprises SMEs. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic this has been one of the worst and most immediately affected sectors, with almost overnight losses of customers, damaged supply chains, significant job losses and financial hardship. For many in the hospitality sector, IP asset largely meant brand assets such as trade marks, and domain names or databases of clients or suppliers. However, the challenges brought about by the pandemic has not only forced business to better utilise and, in many cases, monetise these assets, but more importantly it has also set about a degree of innovation in the industry, accelerating changes already underway but also forcing many business to reinvent themselves and develop new online offerings, new supply chains and new business models. In this context, intangible assets are likely to become increasingly important for this industry in protecting these innovations and helping businesses create a niche for themselves and cement their market position.

Analysis

These changes for SMEs in the F&B industry have included changes in business models, changes in operations and procurements processes as well as fast-tracking digitalisation and accelerating emerging technologies in this sector. The uncertainties have required businesses to be better at managing risks, business performance, and cash flows as well as imagining new routes to revenue generation and prioritisation business models incorporating digitalisation, the latter being an important tool in aiding recovery of this sector moving forward[1]. It is important that SMEs impacted by COVID-19 recognise the impact on their business at an early stage and understand what actions will be required to restart their business and survive the COVID-19 storm[2]. It is clear that IP will be an important part of this process[3].

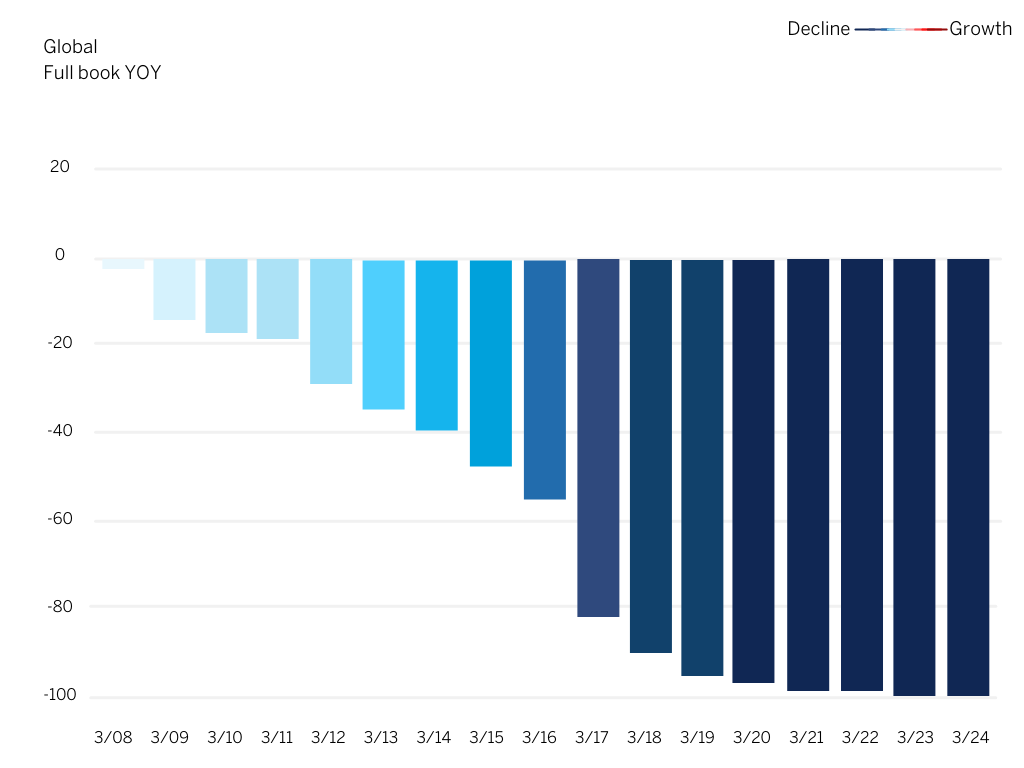

A China Cuisine Association and Deloitte China survey indicated that 94% of companies interviewed have had their dine-in services severely affected – in many cases by an 80% decline in dine-in customers. This is especially evident in the chart below, reflecting the year-on-year change in seated restaurant diners globally during the global spread of the coronavirus in March 2020.

Figure 1: Year-over-year daily change in seated restaurant diners due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic globally in March 2020.

In the UK alone, it is expected that approximately 3.2 million people work in the catering industry and are impacted by COVID-19 job losses, furloughs or pay cuts. Many venues have expanded existing online ordering services by offering food and recipe boxes and supplying customers with fresh ingredients for their favourite meals at home. Some restaurants and cafes are also providing hampers for sale online to customers and may continue to use this as an additional source of income moving forward. With the explosive growth of online food delivery platforms such as Just Eat, Deliveroo and Uber Eats, it is quite straightforward for regular restaurants and cafes to provide such “take away” services, especially to those who may be house bound on a long term basis such as those with existing medical conditions or the elderly.

SMEs and F&B venues across the world are meeting these challenges through automation of process (robotics), development of online ordering and payment systems (e.g. QR codes for online menu access and payment), while also enabling contract tracing, a requirement in many countries during the current pandemic, while others have also introduced innovation air and surface purification technologies to ensure the air present is purified and any viral or bacterial contaminants have been neutralised. Many of these innovations surrounding software platforms, robotics, and food preparation systems are well protected by suitable IP rights and likely represent significant changes in the industry, many of which will continue into the future, with licensing opportunities for these technologies also representing potential additional revenue streams for affected businesses. For example, Creator, a San Francisco based restaurant, already known as innovators due to their robot made hamburgers, have sealed off their restaurant and now deliver their meals via a patent protected pressurised transfer chambers, which avoid ingress of air from outside as well as having a self-sanitising conveyor surface. The company has been granted patents for aspects of its hamburger making robot and has also applied for patents for its COVID-19 inspired food delivery system.

Despite the opportunities in terms of active IP exploitation underpinning innovative business opportunities, IP challenges remain. With ongoing lockdowns and significant economic recession still likely to come, many businesses in this sector may also suffer from potential risk of non-use of their trade marks. Although this period of non-use (which is five years in Europe and three years in the US) may not appear to be immediately worrying, it is not clear if many businesses will continue to meet requirements, especially in the longer term[4]. Moreover, as restaurants expand their delivery activities and dining in becomes only a part of the offering, there may be increasing pressure on F&B businesses to protect recipes through NDAs due to limitations protecting recipes using copyright and trade secrets, as well as the brand of the venue and the personal brand of the chef. This will require the broader understanding of brand assets by the business, the means of protection and, importantly, the means by which the assets can be monetised and deployed to generate revenues. For example, JD.com livestreamed a club experience and partnered with a number of alcoholic drink brands, encouraging viewers to have a drink while watching. This boosted sales of both beer and spirits. This is further demonstrated in the silence of Corona Beer in the face of significant memes and online jokes, shows the company distancing itself and the brand from unfortunate potential damage[5].

Naomi Korn Associates is one of the UK’s specialists in copyright, data protection and licensing support services.

Mathys & Squire Consulting is an intellectual property consulting team that can support all businesses in capitalising intangible assets.

Naomi Korn Associates and Mathys & Squire Consulting are working in partnership across multiple industries to provide innovative consultancy IP support services.

[1] Grant Thornton, Raymond Chabot (2020): Preparing SMEs for a rapid recovery from the COVID-19 crisis, Grant Thornton

[2] Deloitte (2020): Covid-19 – Small Business Roadmap for Recovery & Beyond: Workbook, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

[3] EPO (2021): Study highlights economic benefits of owning intellectual property rights – especially for small businesses, EPO

[4] Allen & Overy (2020) Issues brand owners need to consider during the Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic to protect their IP portfolio, https://www.allenovery.com/en-gb/global/news-and-insights/publications/issues-brand-owners-need-to-consider-during-the-covid-19-coronavirus-pandemic-to-protect-their-ip-portfolios

[5] Accenture (2020): COVID-19:5 new human, Accenture

T 2314/16 helps to clarify the European Patent Office (EPO)’s approach to business methods. The Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.01 made a favourable decision on patentability of an invention relating to influencer reward distribution for an online marketing scheme. This decision is likely to be helpful for applicants innovating in commercial, financial and service industries, which are often difficult to protect at the EPO.

Business methods and the notional businessperson

Subject matter solely relating to methods of doing business or to present information has long been excluded from patentability under European patent law (Art. 52(2)(c) EPC). For example, European patents cannot be obtained for methods of accounting, advertising, or task scheduling as such.

However, for business methods which involve a mixture of non-technical business features and some technical features, patents may be obtained if the technical features (or their interaction with the business features) produce a technical effect and are inventive over the prior art. For example, features such as using a smartphone connected to a server to gather financial data, as well as storing and processing the data to make a decision (such as how much to charge a customer) may be considered technical and therefore, escape the exclusion of Art. 52(2)(c) EPC, despite being business-related.

Nonetheless, the EPO has historically taken a strict approach when determining which features of these mixed type inventions provide a technical effect. For instance, in T 1147/05, Board 3.5.01 rejected arguments that collecting and processing real world data for providing environmental impact information achieved a technical effect.

In the absence of a statutory positive definition of the term ‘technical’ against which to measure features of an invention, as part of their assessment of the inventive step, the EPO considers whether the features lie within the competence of a notional technically skilled person or of a notional businessperson. Those features lying within the competence of a technically skilled person are considered to contribute to the technical character of an invention, and only those features may be considered for inventive step. It follows that if all features are within the remit of the businessperson, there is no ‘invention’ in the legal sense.

However, in reality, the expertise of technically skilled people and businesspeople often overlap, so artificially separating the two for the sake of this legal test can produce grey areas when determining the patentability of subject matter.

Board 3.5.01 attempted to clarify matters in T 1463/11 and T 144/11 by indicating that inventions which simply solve the problem of implementing a business requirement are rarely patentable, again upholding a relatively strict interpretation of the law.

T 2314/16 – A favourable decision on patentability

In June 2016, Rakuten Inc. filed an appeal against a decision from the Examining Division to refuse their patent application for lack of an inventive step.

The application related to distribution of rewards to users of an affiliate marketing scheme, such as social media influencers who endorse products or services. In this scheme, each influencer is allocated an area of an advertisement banner displayed on a website. When a website visitor clicks on the banner, the influencer whose area is clicked on receives a reward. Over time, rewards are collected and then distributed according to the area sizes: an influencer with a larger share of the banner will typically be clicked on more often and therefore receive greater reward. The relative sizes of the areas can be adjusted to match the amount each influencer contributes to the advertising; if one influencer attracts many clicks, their area of the banner may be increased.

The claims refused by the Examining Division essentially specified a web server that provides a web page with the advertisement banner, acquires coordinates of clicked locations on the banner, matches those clicked locations to influencers, and stores associated reward information. The Examining Division found a lack of inventiveness on the basis that the invention’s distinguishing features, when compared to known HTML server-side image maps (which allow web browsers to send click coordinates to web servers), “did not go beyond a mere automation of the business-related aspects”. However, the Examining Division provided no reasoning as to why certain features were deemed non-technical.

In their decision of December 2020, Board 3.5.01 deemed the technical problem solved by the invention to be the implementation of a business method, namely reward distribution. Importantly, they also clarified which features were part of the business requirements and which were part of the technical implementation of those requirements.

In this regard, the Board held that the “specification of the business method ended with how to determine the reward distribution ratio”, and that devising an approach that involved dividing an advertisement display area into sections and allocating each area to an influencer required an understanding of “how a website is built, and in particular how an image map works”. Thus, these features were considered to be within the competence of the technically skilled person, and therefore were part of the technical solution and should be evaluated for obviousness.

The Board went on to state that, when tasked with implementing reward distribution to a number of users and starting from known HTML server-side image maps, the allocation of users to partial image areas would not be obvious to the technically skilled person. Consequently, Rakuten’s application was granted.

Essentially, this decision builds on previous case law by confirming that the remit of the notional businessperson may end with the statement of the business requirements. The features that arise after this in the process of devising the invention may be attributable to a technically skilled person, and thus may be capable of conferring an inventive step.

However, this decision is key: it clearly defines the boundary between the domains of the technically skilled person and the businessperson, and it does so generously to maximise the range of subject matter that may be considered technical. The decision shows that the EPO is willing to grant inventions for business-related methods, as long as the technical solution is non-obvious.

Outlook

This case demonstrates a more lenient attitude to business-related inventions, which will be welcome news for applicants seeking to protect such concepts. Whether this signifies a shift in the general position of the EPO on business methods remains to be seen, but T 2314/16 looks set to become important case law at least for implementations of business requirements. The decision has been included in the latest update to the Case Law of the Boards of Appeal, so a general awareness of its findings can be expected at appeal and perhaps even at other divisions across the EPO.

Further to the announcement of the National Artificial Intelligence (AI) Strategy in September 2021, the UK Government has now launched a pilot initiative, known as the AI Standards Hub, intended to increase UK contribution to the development of global AI technical standards. The new Hub is currently being trialled by The Alan Turing Institute, supported by the British Standards Institution (BSI) and National Physical Laboratory (NPL).

The Hub aims to:

- Grow UK engagement to develop global AI standards – this will be achieved by assimilating information about technical standards and development initiatives in an accessible, user-friendly and inclusive way.

- Engage the AI community– the pilot hopes to foster a more coordinated approach to develop global AI standards by bringing together the AI community through workshops, events and a new online platform.

- Create educational tools and guidance – focusing on education, training and professional development, the initiative aims to help businesses and other organisations engage with creating AI technical standards, and collaborate globally to develop and benefit from these standards.

- Explore international collaboration – to ensure the development of technical standards are shaped by a wide range of AI experts, in line with shared values, the Hub seeks to explore collaboration with the similar international initiatives.

The announcement comes as new research by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport and the Office for Artificial Intelligence projects that more than 1.3 million UK businesses will use AI by 2040, and spending on AI by UK businesses is expected to reach more than £200 billion by the same date, up from £63 billion in 2020.

The Government has also already launched a consultation on intellectual property (IP) and AI as part of the National AI strategy. The consultation period has now closed, and we await the publication of a formal response from the Government in due course.

You can read the full UK Government announcement about the AI Standards Hub here.