Women throughout history continue to make their mark creating innovations and discoveries that impact our lives today. To celebrate International Women’s Day 2021, we reflect on inspiring female inventors in each decade since 1910 – when Mathys & Squire was first founded – to demonstrate the significant value that realising new ideas and inventions can bring.

1910s

- 1914: Florence Parpart

Parpart invented and filed a patent for the first modern electric refrigerator, which she initially marketed and sold to companies in America. The refrigerator represented a revolution for conserving food and is today an integral appliance in any kitchen.

1920s

- 1921: Ida Hyde

Hyde created one of the earliest models of an intracellular micropipette electrode, which can be used to stimulate and monitor individual cells. This technology is still widely used in science laboratories today.

1930s

- 1935: Katharine Blodgett

An American physicist and chemist, Blodgett is known for her work on surface chemistry and invented a revolutionary ‘invisible’, or non-reflective, glass coating, which is used in making camera lenses, microscopes and eyeglasses.

1940s

- 1941: Hedy LaMarr

Although primarily an actress, during World War II LaMarr created a frequency-hopping communication system, which could guide torpedoes without being detected. Her work paved the way for the introduction of Wi-Fi, GPS and Bluetooth to the modern world.

1950s

- 1957: Gertrude Belle Elion

Elion helped to develop numerous life-saving drugs for the treatment of diseases such as malaria, herpes, cancer and AIDS. Along with George Herbert Hitchings, she invented the first immunosuppressive drug, Azathioprine which was initially used for chemotherapy patients, and eventually for organ transplants. She was awarded the 1988 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine.

1960s

- 1965: Stephanie Kwolek

In 1965, Kwolek discovered that polyamide molecules can be manipulated at low temperatures to form incredibly strong and stiff materials, which is used to make Kevlar®. Originally Kevlar® was used to create lightweight, strong tyres for vehicles, but today is best known for body armour, such as bulletproof vests.

1970s

- 1971: Evelyn Berezin

An American computer designer, Berezin created the world’s first computerised word processor and founded her own company to bring her inventions to market. The first model was the size of a small refrigerator. She also developed computer-controlled systems for airline reservations.

1980s

- 1984: Rachel Zimmerman

At the age of just 12, Zimmerman invented a device called the ‘Blissymbol Printer’ that allowed people with speech disabilities to communicate non-verbally – using symbols on a touchpad translated to written language. Her invention has been recognised globally and she has received several awards for her achievements.

1990s

- 1991: Ann Tsukamoto

Tsukamoto is an inventor and stem cell researcher who made a significant breakthrough in cancer research. She co-patented a process for identifying and isolating human stem cells found in bone marrow, which is today used to treat blood cancer, saving hundreds of thousands of lives.

2000s

- 2009: Pratibha Gai

Gai created the in-situ atomic-resolution environmental transmission electron microscope (ETEM), which allows for visualisation of chemical reactions at the atomic scale. Her invention has been used worldwide by microscope manufacturers, chemical companies and researchers.

2010s

- 2012: Deepika Kurup

Kurup is a clean water advocate and as a teenager, after seeing children in India drinking dirty water, she invented a water purification system (photocatalytic composite material) that removes 100% of faecal coliform bacteria from contaminated water using solar energy.

2020s

- 2020: Sarah Gilbert & Catherine Green

Gilbert & Green are two of the leading scientists behind the Oxford/Astra Zeneca Coronavirus vaccine developed in record time amidst the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, saving lives and bringing hope to the entire world.

The inventors listed above are just a small selection of the vast number of women who have developed and, in some instances, patented innovative products that revolutionise the world we live in. At Mathys & Squire, we are privileged to work with innovators across a range of highly dynamic sectors and celebrate their significant technical contributions not just on International Women’s Day, but every day.

World Trademark Review has featured Mathys & Squire in its latest edition of the WTR 1000 directory, highlighting the firm’s “professional, responsive and wide-ranging service” and its ‘unimpeachable record in protecting and enforcing the cornerstone brands of top UK and international companies’. Trade mark partners Margaret Arnott and Gary Johnston have also maintained their statuses as recommended individuals in the 2021 directory.

Now in its eleventh year, the WTR 1000 shines a spotlight on the firms and individuals that are deemed outstanding in this critical area of trade mark practice. The WTR 1000 remains the only standalone publication to recommend individual practitioners and their firms exclusively in the trade mark field, and identifies the leading players in over 80 key jurisdictions globally. Mathys & Squire has been recommended for its outstanding work in the trade mark field, specifically in the ‘United Kingdom: England’ jurisdiction, under the ‘Firms: trade mark attorneys’ category.

In this latest edition, published on 15 February 2021, partners Margaret Arnott (recommended in the categories of ‘Enforcement & Litigation’ and ‘Prosecution & Strategy’), and Gary Johnston (recommended in the category of ‘Prosecution & Strategy’), who co-head the Mathys & Squire trade mark team, have received the following feedback:

For more information and to see the full WTR 1000 rankings, please click here.

In a number of recent cases, patent offices have refused to allow artificial intelligence and machine learning systems to be credited as inventors in patent applications. How are patent systems to respond to the advent of potentially omniscient artificial intelligence (AI)?

In this article for The AI Journal, Mathys & Squire partners Sean Leach and Jeremy Smith consider what impact this might have on the law of invention.

The basis of the patent system is that in return for explaining to the world how to make their invention, an inventor is rewarded with a limited monopoly subject to certain requirements. Firstly, the protected innovation must meet an ‘inventiveness’ criteria and, secondly, the innovation must be described in sufficient detail to ‘enable’ a notional skilled person to make the invention. This is to allow others to learn from the inventor’s contribution so as to foster further creativity and discourage secrecy.

In this context, AI presents a thorny problem. If an AI makes an invention, should that AI be named as the inventor? If so, should the AI be sole inventor? These questions might all seem academic, but they raise a significant public policy question: how are inventors and businesses to be rewarded fairly for sharing their innovations?

The question of inventorship: If an AI makes an invention, should that AI be named as the inventor?

Sean: No. The AI is not a person; it does not have legal personality, and never could. People have drawn parallels to the animal rights questions raised when PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) attempted to have a monkey named as the owner of copyright in a selfie it took with a stolen camera. That is an irrelevant distraction. AI can never have legal personality, not only because it is not an ‘intelligence’ in the human sense of that word, but also because it is not possible to identify a specific AI in any meaningful sense. Even assuming the program code for the AI was to be specified, is the ‘inventor’ one particular ‘instantiation’ of that code? Or is any instantiation the inventor? If two instances exist, which is the inventor? The answer to this question matters crucially in patent law because ownership of an invention depends on it.

Jeremy: It may be true that, in the current patent system, an AI has no legal personality and cannot, therefore, be named as inventor. However, that does not mean that the patent system should not be adapted to require an AI contributor to be named in some way – whether as an ‘inventor’ or as something else (e.g. ‘AI contributor’). There may be policy reasons why patent applications relating to AI generated inventions should be made easily identifiable to public. Such patent applications could, for example, incentivise more investment in AIs because the naming of the AI would act as a showcase for an AI’s capability and could be used by the AI’s creators as part of a ‘royalty-per-patent’ business model. At the same time, naming the AI offers the public greater transparency in relation to how inventions are generated and provides a convenient way to track the potentially increasing contribution made by AIs to providing innovative solutions to the problems faced by mankind.

As to the practical question of how AIs should be identified, there are ways this could be formalised – for example by referring to an entry in an official register of creative AIs that an AI would have to be present on for it to be named as an inventor.

Should the AI be sole inventor?

Our shared view is that a human inventor can – and indeed must – always be named. It is through inventorship that the right of ownership is ultimately determined.

The real question is who, whether aided by AI or not, conceived the solution to the technical problem underlying the invention? For example, if an AI is created with the sole purpose of generating an invention to solve a particular problem, then a creator of that AI is probably also an inventor both of the AI generated invention and the AI itself. If someone identifies a problem to be solved and recognises that a commercially available AI can be used to generate a solution to that problem, then that person could also be the inventor of the resulting AI generated invention. This is not different to the situation in which a software design package is used as a tool of the inventive engineer’s trade.

If an AI is set to work within much broader parameters the inventor might be the person who: identifies the required technical inputs for the AI; identifies the best sort of training data and how best to train the AI to solve the problem; or recognises that the output of the AI solves a particular problem.

These questions may seem speculative and somewhat academic, but we believe the answers to these questions genuinely matter in practice. One of the aims of the patent system is to balance the requirements of: allowing innovators to obtain a just reward for their work; ensuring that protection is granted for innovations that are worthy; and encouraging the innovators make their innovation public. As AI technology is increasingly used as part of the innovation process and, at the same time, the AI industry becomes a more significant contributor to the economy, the patent system needs to adapt to ensure that it encourages, rather than stifles, the use of AI in the innovation process.

This article was originally published in The AI Journal in February 2021.

10 February 2021: This article has been updated to reflect our understanding that the Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.02 has made a referral to the Enlarged Board about the legality of holding Oral Proceedings by videoconference without the consent of all parties. The wording of the referred question(s) has not yet been made public.

The EPO has long offered the option of holding Examining Division Oral Proceedings via videoconference, well before the disruptions caused by Covid-19 this year. As a firm, Mathys & Squire has embraced the use of videoconference for Examining Division oral proceedings for many years now and have bespoke videoconference rooms in a number of our offices that are frequently in use.

In our experience, videoconference oral proceedings before the Examining Divisions – of which the firm has held over 250 to date – work well. We have found them to be well suited to a discussion of the technical and legal issues at hand, and a clear dialogue can be conducted between the presenting attorney and members of the EPO. Not only does the use of videoconference have clear environmental benefits in that it reduces the need for air travel, but it also allows an attorney to prepare and present from their preferred location and removes unnecessary distractions.

With the advent of Covid-19, in April 2020 the EPO decided that all Examining Division hearings would be held by videoconference unless there were “serious reasons” not to. Videoconferencing was also offered for hearings before the Opposition Division, provided there was “the agreement of all parties”.

For Examining Division hearings, this was generally widely welcomed in the profession and allowed the prosecution of patent applications to continue despite the restrictions imposed by Covid-19. Having attended many Examining Division hearings by videoconference from home under lockdown restrictions, the authors of this article have personally found the process to be reliable, clear and convenient. Equally, the process appears to have been convenient for EPO Examiners too, allowing them to attend virtually from different locations.

Opposition proceedings

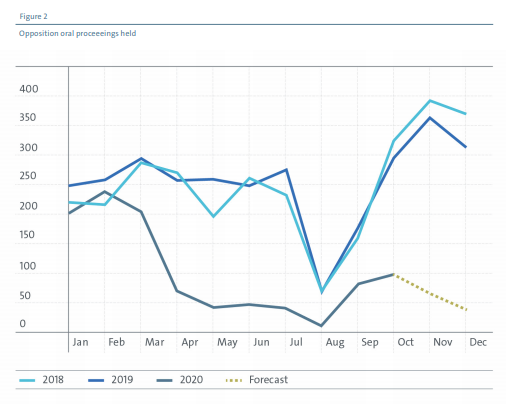

For Opposition proceedings, however, uptake has been low – a progress report published by the EPO noted that the cumulative number of videoconference opposition hearings between May and October 2020 was less than 250, far less than the normal of approximately 250 a month in 2018 and 2019.

This may reflect the greater level of discomfort felt by parties when it comes to relying on a virtual hearing in cases which are contentious (and, hence, more valuable). It might also explain why the largest increase in opposition ‘backlog’ is in the healthcare, biotech and chemistry sector, which has seen a 24% increase in the 12 months to September 2020, versus 15% in mobility and mechatronics and only 7% in information and communications technology.

Faced with this lack of uptake, and to prevent an insurmountable backlog developing, the EPO recently issued a notice (dated 10 November 2020) indicating that as of 4 January 2021 all oral proceedings before both Examination and Opposition Divisions would be held via videoconference, and that videoconference oral proceedings could only be postponed for “serious reasons” and if this was the case they would be postponed until after 15 September 2021. The definition of “serious reasons” is not clear, but an EPO notice indicates that one example of a “serious reason” is where “the demonstration or inspection of an object where the haptic features are essential”. The notice makes clear that “sweeping objections against the reliability of videoconferencing technology or the non-availability of videoconferencing equipment will, as a rule, not qualify as serious reasons in this regard”.

Opposition Division hearings are public, and many of the clients we work with would be interested in attending opposition division oral proceedings, but due to cost and/or travel commitments cannot attend in person. The move to switching Opposition Division hearings to videoconference will allow clients to dial in and watch the proceedings in real-time, thus improving access to justice.

Appeal proceedings

With the switch to videoconference oral proceedings for both Examination and Opposition proceedings, the EPO Boards of Appeal have also been conducting some oral proceedings via videoconference where there is agreement with the parties concerned. The Boards of Appeal confirmed in May 2020 that a videoconference is permissible for an appeal hearing (T 1378/16). From May to October 2020, over 120 appeal hearings have been heard via videoconference; although this is, as for opposition hearings, much less than the total number which would be expected over the same period.

The EPO Boards of Appeal now propose to formalise this change in practice by amending the Rules of Procedure of the Boards of Appeal (RPBA). Following a recent consultation, the Boards intend to add a new Article 15a to the RPBA which would allow the Boards to schedule hearings by videoconference, whether or not the parties to proceedings agree to this. The changes will likely come into effect in April 2021, but the guidance from the EPO suggests that the Boards will start to adapt their practice from January 2021. We therefore expect to see the Boards scheduling hearings by videoconference of their own motion starting early in 2021.

In the consultation on the changes to the RPBA, concerns were expressed in some quarters about a Board insisting on a videoconference hearing if not all parties to proceedings agree to do this. We understand that a question has now been referred to the Enlarged Board of Appeal in case T1807/15 to clarify the extent of the Boards’ powers in this regard. The wording of the question is not yet known.

During 2020, the videoconference facilities at the Boards of Appeal have primarily been set up towards all parties attending remotely (T 492/18 at reason 2.4). However, the possibility of hybrid oral proceedings, in which some parties attend in person and others attend remotely, is permitted under the proposed new Article 15a. In our experience, some Boards have been resistant to hybrid oral proceedings, and it remains to be seen whether the Boards really make use of this option.

The authors have experience of conducting appeal proceedings by videoconference and have found it to be both convenient and reliable.

With bespoke videoconference facilities in our offices throughout the UK, and with an office in Munich, we are well placed to handle both videoconference oral proceedings and also in-person hearings, whether these take place in front of the Examining and Opposition Divisions, or the Boards of Appeal.

In this series, our IP experts will reflect on some of Google’s top trending topics throughout the unprecedented year of 2020. In our final article of the series, partner Juliet Redhouse and technical assistant Jonathan Israel explore arguably the most significant of all topics to come out of 2020 – the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing vaccinations.

2020 marked a year of global upheaval following the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the year ended with more positive news following the regulatory approval of a number of vaccines for the start of the largest global vaccination campaign in history.

The world’s most innovative life sciences companies and institutions have risen to the challenge of generating safe and efficacious vaccines for global distribution at rapid speed. The pace at which these vaccines were developed largely arose from the repurposing of existing vaccine technologies to target the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus variant. However, clearly challenges have been overcome in both the design of the vaccine and its large-scale production, which will have resulted in new patent applications in 2020.

With 64 vaccine candidates in clinical development and a further 173 in pre-clinical development (source: WHO), 2021 should see the approval of further vaccine candidates. We are also likely to see continued focus on the emergence of new coronavirus variants. Some innovators have already started to shift their focus towards the development of vaccines tailored to new variants, and these efforts are likely to be accompanied by new patent filings.

We may also see patent filings around the optimisation of vaccine dosage regimens. The majority of the COVID-19 clinical vaccine candidates employ a two-dose regime, in the form of prime and booster doses, which has itself raised controversy over the benefits and trade-offs over lengthening the interval period. Moving into 2021, as the risk from new variants is brought into sharper focus, we may see some innovators adjusting the dosage regimen to compensate. For instance, a third booster dose has already been mooted as a possible future requirement and clinical trials are already planned, while the benefits of adjusting the prime dose have also been explored.

2020 has also seen an urgent need for COVID-19 treatments, which have until now been met by the repurposing of existing medicines. The UK Recovery trial was the first in the world to provide clinical trial evidence of a safe and effective COVID-19 treatment in the form of dexamethasone, a steroid that has been in existence for decades and has a well understood mechanism of action. In 2021, UK approval for antibody treatments tocilizumab and sarilumab has followed. Encouraged by these findings, and with improved understanding of the mechanisms of COVID pathogenesis, innovators are likely to intensify research efforts towards repurposing existing therapies to strengthen the therapeutic armoury. We are therefore likely to see new patent filings centred on further medical uses of existing therapies.

As 2021 moves into brighter times, it is likely that new tools will be required to adapt to a world living with COVID-19. We would particularly expect COVID-19 diagnostics to continue to play an important role, predominantly to monitor local COVID flare-ups and for targeted surveillance of new mutations. As domestic and international travel begins to restart, demand for reliable and rapid diagnostic tests will intensify and further investment and development in this area is likely. Further innovations in the form of protective measures for offices and public transport are also likely to be enhanced for if – and when – the workforce returns to the office.

Previous articles in our 2020 trending topics series include: ‘Tiger King – Murder, mayhem, mullets… and trade mark law‘ and ‘Face masks and design protection‘.

In this series, our IP experts will reflect on some of Google’s top trending topics throughout the unprecedented year of 2020. In our second article, associate Max Thoma considers the small (but mighty) face mask, and how its design might be protected under registered design law.

2020 was notable for many reasons, including the sudden appearance in the Western world of a new consumer article that almost everyone felt a need to acquire – the ubiquitous face mask. From the humble blue disposable medical mask, to the lovingly homemade colourful mask, to the high-end designer models, face masks were everywhere in 2020 and are likely to stay ever-present in our pockets, in our bags and (of course) on our faces, until deep into 2021 at least.

Predictably, the emergence of this new category of products saw designers seeking to impart their own spin on the face mask and file registered designs to protect their new creations. The UK design register shows numerous designs for face masks, together with packaging for such face masks. There are also several registered designs for protective wallets and bags for face masks, along with more exotic items such as combined t-shirts and masks – might such products be a growth area in 2021? Whatever the product, designers should make sure that appropriate registered design protection is sought based on carefully prepared drawings which clearly identify the key features for protection (and, ideally, which ‘disclaim’ features of lower importance).

2020 was also notable in registered design terms for being the final year during which EU registered designs covered the UK. The Brexit transition period expired at the end of December 2020, so it is now necessary for applicants to seek design protection in both the EU and UK separately. Existing EU registered designs were automatically ‘cloned’ in corresponding UK designs upon the expiry of the transition period, so designers with already registered designs should not have lost any rights. Although the need to file registered design applications in both the EU and UK is burdensome, the UK design system is fortunately substantively similar to the EU system and involves very low official fees, meaning that new combined UK and EU design applications involve only a small increase in cost and complexity as compared to filing only a EU registered design application (as most applicants did prior to Brexit).

Whether your new design relates to a face mask or something else entirely, you register it in both the UK and EU separately to ensure its protection. Visit our Brexit page for more information.

Other articles in this 2020 trending topics series include: ‘Tiger King – Murder, mayhem, mullets… and trade mark law‘ and ‘COVID-19 vaccinations‘.

In this series, our IP experts will reflect on some of Google’s top trending topics throughout the unprecedented year of 2020. Our first article, written by trade mark associate Robin Richardson, explores the significance of brand protection, using hit Netflix series Tiger King as a case study.

The 2020 lockdowns were a difficult time for many. Some turned inwards, some turned to exercise, but most turned to Netflix. Of all the popular series and films released throughout 2020 by the world’s largest subscription streaming service, one docu-series truly took the crown from The Crown, and why not – it is after all Tiger King!

For those who have not had the opportunity to ‘Baskin’ all the glory that is the tale of Tiger King, the documentary centres around the rivalry between two individuals, Joe Exotic and Carole Baskin. Joe Exotic (who sports a blonde mullet which would make most 80’s rock stars green with envy) ran a questionably legal big cat zoo in Wynnewood, Oklahoma which drew the wrath of Carole Baskin, a self-proclaimed animal rights crusader who founded an equally questionable big cat ‘rescue’ centre.

The rivalry between the two, which should have centred around the care of big cats, ultimately turned to a personal feud so bitter that it lands Exotic in jail with, amongst other severe animals rights violations, a conviction for attempting to hire a hitman to kill Baskin.

But what exactly does the documentary have to do with intellectual property (IP) law? Well, Baskin’s goal was purportedly to shut down Exotic’s zoo permanently. Whilst Exotic’s own actions may have landed him in jail, it was Baskin’s successful trade mark and copyright disputes which handed her control of Exotic’s zoo in June 2020.

At the centre of the disputes was Exotic who, in his quest to taunt his rival and damage Baskin’s corporation, decided to use her corporation’s trade mark ‘BIG CAT RESCUE’ in relation to a road show exhibiting big cats across the US. Exotic, however, did not use an identical trade mark, instead adding the word ‘ENTERTAINMENT’ to form ‘BIG CAT RESCUE ENTERTAINMENT’, which (unfortunately for him) was not sufficient to avoid an infringement of the registered trade mark. His case was not helped by the multitude of copyright infringements that were levelled against him for the unauthorised use of photographs owned by Baskin and her corporation. In the end, the court ordered that Exotic pay $953,000 in damages (primarily relating to the trade mark dispute) and legal fees. With Exotic unable to pay the order, the court ordered control of the zoo to be handed over to Baskin in June 2020.

Exotic’s actions and Baskin’s success highlights both the strength of trade mark and copyright protection, as well as the dangers of not having a grasp of IP law and the implications of infringement when launching a business or sharing content online. Although the case of Tiger King is unusual, to say the least, it does serve as a reminder that proper counsel should always be sought before using a trade mark or sharing content that you do not own – after all that’s what all the “Cool Cats And Kittens” would do (to quote Carole Baskin)!

Other articles in this 2020 trending topics series include: ‘Face masks and design protection‘ and ‘COVID-19 vaccinations‘.

In recent news, Japanese car maker Nissan has confirmed that it will localise manufacture of its 62kWh battery at its plant in Sunderland. This comes as a welcome boost to UK businesses involved in the automotive supply chain in the North East, many of which the Mathys & Squire team helps to represent.

With the UK government’s commitment that all cars made by 2030 must at least be partly electric, it is clear that electric vehicles are very much part of the future. Nissan’s announcement follows hot on the heels of Britishvolt’s recent news that it would be creating the UK’s first “gigaplant”, creating up to 3,000 jobs, on the site of the former Blyth Power Station in Northumberland. Britishvolt’s £2.6bn investment is a sign of yet further confidence in the expertise and highly skilled workforce in the region.

Having been partners of the North East Automotive Alliance for several years now, and working with some highly innovative businesses in the region, such as Hyperdrive Innovation and BorgWarner, we understand first-hand the skills, expertise and innovation that are coming out of the region and are excited to be working with businesses in the North East to help protect their intellectual property in what is proving to be an international scramble for the investment of future automotive technology.

In this feature by Lawyer Monthly, partners Andrew White and Chris Hamer provide their thoughts on the patent trends to look out for in 2021.

Artificial intelligence – Andrew White

As with recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) looks set to continue to be a trend for 2021. With the publication in Nature in November 2020 announcing that DeepMind’s AI “AlphaFold” will “change everything”, we are likely going to see further developments where AI is used to solve problems relevant to humanity – particular in spaces where AI is used to solve problems in the chemical and life sciences fields, and relevant IP in this area is likely going to more and more relevant as commercial applications come to fruition. Partly in recognition of this, the European Patent Office (EPO) held a Digital Conference in December 2020 on “the role of patents in an AI-driven world”, with the EPO calling AI “one of the disruptive technologies of our time” and recognising that patenting activity in this area has increased dramatically recently.

Patent trends – Chris Hamer

Plant based foods – The growth in this sector is undeniable with the market expected to reach $74.2bn by 2027. With political and social pressure to improve diets, and initiatives such as Veganuary,food manufacturers will invest millions to be able to provide innovative plant based alternatives which truly fool the consumer into thinking they are eating the real thing. Throw into the mix the fact that different countries only have access to certain raw materials and you can see just how difficult the challenge is…

Coronavirus – Much has been written about the vaccines and equipment developed over the last year, and whilst there will continue to be improvements, we expect to see an increase in digital technologies (e.g. virtual reality, network security, digital marketing apps, social media, e-commerce and videoconferencing, etc), which, in the long run, will hopefully drive productivity gains in a new business and social revolution.

Brexit – Now that the UK has officially left the EU, it will be interesting to see if UK and EU law really will diverge as some have feared, or whether the previous decades of harmonisation will generally remain for the foreseeable future.

These comments were first published in the January 2021 edition of Lawyer Monthly Magazine.

At the end of 2020 the German parliament passed (for the second time) the legislation necessary for Germany to ratify the Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA). This followed a ruling earlier in 2020 from the Federal Constitutional Court which nullified the first attempt to implement this legislation due to failure to meet a parliamentary majority of two-thirds as required under the German constitution.

Following the second attempt at enacting the relevant law, it has now been reported that two new complaints relating to the UPCA have been filed with the Federal Constitutional Court. Once again, the court has asked the German President not to bring the legislation into force while these complaints are reviewed. Few details are available regarding the new complaints so far, although it is understood that one of them has been filed by the same party who was behind the previous, successful complaint. It is also understood that a preliminary injunction has been sought by one of the complainants to formally prevent the German government from ratifying the UPCA pending the Constitutional Court’s final decision.

If it comes into force, the UPCA will create a common court system for patent litigation in the participating countries, along with a single patent covering those countries. The project has been beset by repeated delays over the years, and the UPCA cannot enter into force without German ratification. The new constitutional complaints are therefore likely to create further delays. A timescale is not yet foreseeable with any certainty, although the previous constitutional complaint took approximately three years to resolve.

More details will be reported if and when these become available.