The 27th United Nations Climate Change Convention (COP27) concluded on the 20th of November 2022, two days after the scheduled end of the conference. A total of 14 days of discussions were held in Sharm el-Sheikh, with the climate change issues tackled ranging from a review of current targets for net zero carbon emissions to agreement for a global fund to tackle ‘loss and damage’ incurred as a result of the climate crisis.

The participants consisted of representatives from over 190 countries with backgrounds in politics, activism, and enterprise, to name a few. Following the conference’s conclusion, the ‘Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan’ was released, which provides an overview of the key outcomes from the conference and lays out a climate action plan for the years to come. The decisions made within the plan will have implications for many industries by driving technology trends and corresponding changes in the intellectual property (IP) landscape.

Loss and damage

The primary takeaway from COP27 was the ‘breakthrough’ agreement regarding the ‘loss and damage’ fund for vulnerable countries. ‘Loss and damage’ refers to the costs that are being incurred by communities, largely in developing countries, due to the effects of climate change, including rising sea levels from which they lack the resources to recover. These countries are taking the brunt of the climate change damage, while contributing to it the least.

By 2030, developed nations could be forced to pay anywhere between US$160 and US$340 billion yearly to help developing nations adapt to climate change by funding disaster relief, constructing sea walls or breeding crops that can better withstand drought. All of these adaptation methods will require fast paced innovation to help keep up with the implications of climate change. We might therefore expect to see an increase in inventions and patent applications relating to climate adaptation technologies in the years to come.

Energy

Energy was again a key focal point of the COP implementation plan. Commitments were reiterated regarding the urgent need for parties to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions immediately, deeply, and sustainably across all applicable sectors. This includes increasing the use of low emission and renewable energy, energy transition partnerships, and other cooperative initiatives aimed at reducing our dependence on fossil fuels.

An enhanced commitment was made underlining the urgency to accelerate the transition to clean renewable energy between now and 2030 and to make energy systems more secure, dependable, and resilient. This, accompanied by a commitment to a transitional clean energy mix, point towards further growth in the cleantech sector, which is likely to be accompanied by an increase in the protection of resultant inventions and other IP.

Technology deployment

A new technology executive committee has been established alongside other commitments, in order to more efficiently deploy climate mitigating and adapting technology worldwide. The function of the committee is to support joint work programme activities, including technology needs assessments, action plans and roadmaps for nations worldwide. The plan also highlights the importance of cooperation on technology transfer when it comes to implementing new technologies. Firms and countries are encouraged to engage in cooperative activities in order to spread key innovations worldwide, particularly to those countries requiring most adaptation to climate change. The IP implications from this will likely be seen in an increase in collaborative invention efforts, leading to more joint technology developments and joint patent applications.

Mitigation

At COP27, a new mitigation work programme was launched, aimed at urgently scaling up mitigation ambition and implementation, with governments being asked to revisit and strengthen current targets in their national climate plans by the end of 2023 and accelerate efforts to phase down coal power and phase out fossil fuel subsidies.

The work programme will start immediately and continue until 2030, with at least two global dialogues held each year. This work programme should drive new policies and technologies that will hasten the transition to low emission energy systems, including accelerating the deployment of clean power generation and energy efficiency measures, and we therefore expect to see an increase in innovation in this area.

Conclusions for IP

As COP27 draws to a close and we look ahead to the future, it is clear to see the technology trends that might emerge from the decisions that have been taken, and the impact these trends will have on the IP landscape. Cleantech and emission mitigation technologies will likely see a growth, accompanied by a corresponding increase in the protection of inventions and other IP arising from innovations in this area. As countries adapt to climate change, expect to see more and more innovations aimed at reducing the impact of climate disasters, with a particular focus in countries most affected by it. The increase in financial support for innovation will only encourage further growth and innovation across these sectors and a corresponding increase in the protection of associated IP rights.

The unitary effect and the Unified Patent Court (UPC) system comes with a wider aspect as to validity against national prior rights (national applications with an earlier priority date but a publication after the priority date of the European patent (EP)).

Such national prior rights are not relevant as to the grant of an EP but can lead to national validity issues (e.g. a German prior right might restrict validity for the German validation). For national validations, this can be addressed by either directly filing an adapted claim set for the respective country (e.g. Germany) or amend the claim set during a national procedure (nullity or restriction).

In case the respective country is a UPC member state (e.g. Germany) and the patentee selects unitary effect, no national limitation is available any longer. Thus, to limit the Unitary Patent (UP) against the national (e.g. German) prior right, the full UP needs to be limited with effect for all UP countries. Therefore, additional care should be taken while considering a UP when national prior rights are involved.

In a helpful move to assist applicants in this regard, the EPO is now providing, as a non-binding service, additional information on national prior rights with the Rule 71(3) EPC ‘notice of allowance’ communication. In summary, the EPO will now perform ‘top-up’ searches whilst gearing up to issue a notice of allowance, toward identifying any national prior rights, while providing an indication as to their prima facie relevance. Any researched relevant national prior rights will then be flagged to the applicant, as a courtesy, with the notice of allowance communication. This search will be performed at no additional cost (and without any need to specifically request it) and will be carried out for all EP applications where the notice of allowance communication was ‘triggered’ on or after 1 September 2022.

Thus, this additional top-up search effectively provides an additional layer of quality control. It will remain the applicant’s responsibility to perform a careful assessment of any national prior rights, and take any action considered necessary. The need to act will be particularly important where the UP and the UPC are concerned.

As many practitioners in the field will be aware, the rapid pace in the deployment and use of standardised wireless technologies, such as 3G, 4G and 5G cellular technologies, has seen wider interest in the use of standards and the licensing of patents essential to those standards – so called standards essential patents (SEPs).

In December last year, the UKIPO published a call for views on SEPs and innovation, in the context of challenges faced by industry. The UKIPO has recently published the response, in which six key themes were identified by respondents, namely:

- the relationship between SEPs, innovation, and competition, and what actions or interventions would make the greatest improvements for consumers in the UK;

- competition and market functioning;

- transparency in the system;

- patent infringement and remedies;

- licensing of SEPs; and

- SEP litigation.

The UK Government intends to use the evidence received to date, and to engage further with businesses, to determine what actions it takes next including whether any government intervention is required. It will be particularly interesting to note if the UK Government decides to take any active intervention in the SEP arena, particularly in view of the landmark Unwired Planet decision, which confirmed that English courts are suitable as forums for SEP disputes at a global level.

It is understood that any significant policy interventions will be subject to public consultation, and that further updates are expected in 2023.

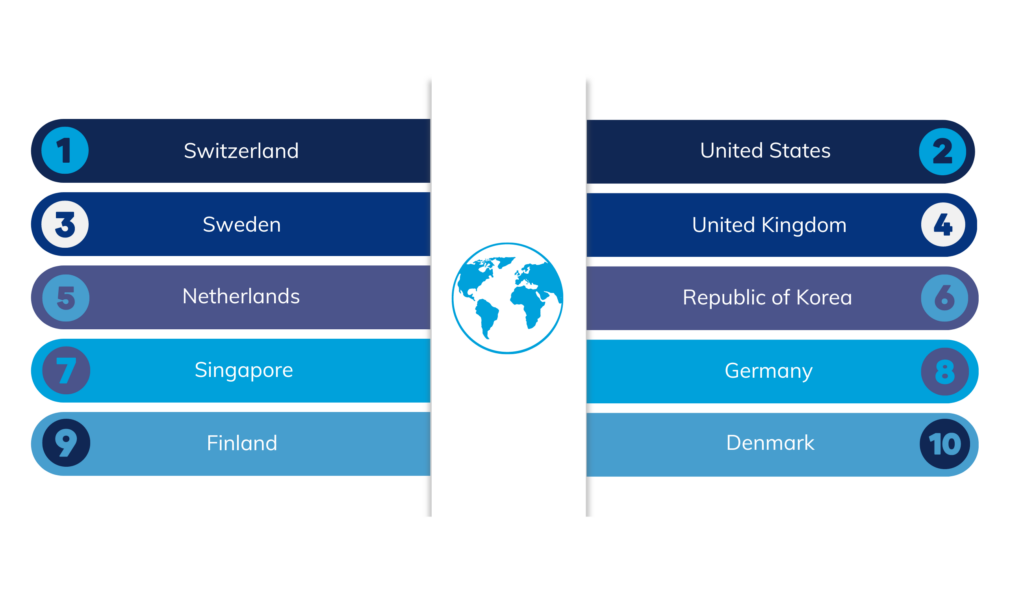

The World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) has officially released the 2022 Global Innovation Index (GII). The GII evaluates 132 countries, aiming to capture the position of their innovation ecosystems, looking at factors such as science and technology, labour productivity, industry diversification and creative goods exports.

For the twelfth year in a row, Switzerland has topped the index, followed by the United States, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. When looking at the countries improving their GII placement, China is quickly approaching the top ten, whilst India has entered the top 40 for the first time.

Global innovation hubs and China’s race to the top of indicator rankings

The GII also looks at the biggest technology innovation clusters for 2022. These ‘science and technology hubs’ look at the innovation centres in the world with the highest density of scientific authors and inventors. For the year 2022, the top science and tech hub is Tokyo–Yokohama, followed by Shenzhen–Hong Kong–Guangzhou (China and Hong Kong), Beijing (China) and Seoul (Republic of Korea). These clusters represent innovation output at a local level, rather than the global scale of the broad GII, and recognise that technology innovation can indeed be a localised phenomenon, shedding light on the communities of innovators worldwide.

It is also of note that Cambridge in the United Kingdom has risen to the global no.1 position in respect of science and technology intensity, that is the sum of patent and scientific publication shares divided by the area’s population. Mathys & Squire’s Cambridge office is proud to support the innovative companies and entrepreneurs that have contributed to this world-leading innovation ranking.

Furthermore, China’s growth within the GII has not gone unnoticed. Climbing to eleventh place in the global ranking indicates China’s recent intentions to foster a more innovative environment for their domestic inventors. When looking more granularly at the specific indicators used to determine the index, China officially ranks first for nine of out of around 80 indicators. These include key innovation areas such as patent by origin, labour productivity growth and PISA scales in reading, maths and science.

Future innovation trends – supercomputing and biotechnologies

China’s recent growth is not the only key takeaway from the GII. The WIPO also produced a list of future innovation trends to look out for, which are referred to as ‘innovation waves.’

The first of two developments is the digital age innovation wave, built around growth in supercomputing and artificial intelligence. The developments within this industry, particularly when considering intellectual property (IP), have already been seen recently in UKIPO’s guidance on inventions created by AI and their patentability. Increasingly, people are considering the future of IP through the lens of AI creations.

The second growth and innovation wave is built around breakthroughs in biotechnologies, nanotechnologies, new materials and other sciences. This trend surrounds the world of hybrid science, whereby the natural environment and modern technology interweave to generate technologically advanced, green solutions. The implications of the growth of nanotechnology stretch far beyond green tech; they possess the capability to expand to engineering and medical device innovations, with future potential to turn science fiction into reality.

It is apparent these two waves indicated by the WIPO will face some serious hurdles when it comes to their diffusion and adoption by sectors worldwide. These innovation waves, alongside growth trends highlighted in the 2022 results, are sure to make for an interesting year when it comes to analysing global development, prior to the 2023 GII. The role of IP during this time will be to ensure inventors have the security necessary to continue working on their new innovations, in order to foster a more fruitful environment for knowledge transfer, creativity and invention.

The United Nations’ 27th Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties (COP) will run from 6 – 18 November 2022 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. The Conference brings together politicians, activists, citizens and business representatives from over 190 countries to discuss tackling global temperature rises, strengthening our ability to adapt to climate change, and an alignment in the flow of finance to help achieve climate action goals.

The climate crisis is one of the greatest challenges facing humanity today. With more frequent and severe climate-related disasters such as floods, wildfires, droughts, and hurricanes, nations around the world are working together to develop solutions that will reduce greenhouse gases emissions and protect our planet for future generations.

At COP27, political leaders from around the world will come together to discuss how we can accelerate climate action globally. They will review each nation’s performance against the targets for reducing carbon emissions to net zero by 2050 and developing renewable energy technologies that help mitigate climate change impacts on habitats like forests and oceans. Additionally, they will be looking at ways to increase climate financing so that vulnerable communities in developing countries can access the resources they need to adapt their infrastructure and build resilience against climate change. Without these resources, these communities are at risk of experiencing devastating impacts such as extreme weather events, food shortages, and water scarcity.

Technological developments offer potential solutions to the challenges of climate change. Innovative climate solutions are emerging every day, from businesses that reduce emissions through carbon capture and storage, to communities that embrace renewable energy sources like solar and wind power.

What are the goals of the COP27 summit?

Since the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015, almost all countries are committed to:

- Keep average global temperature rises below 2°C and ideally 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels.

- Strengthen the ability to adapt to climate change and build resilience.

- Align finance flows with ‘a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.’

Aside from reviewing countries’ progress against these objectives, COP27’s agenda is aimed at achieving further progress in the following areas:

Mitigation

Having reviewed the progress against goals set out in the Paris Agreement (COP21) at COP26, nationally determined contributions (NDCs) proved to be insufficient to limit global warming to the levels agreed in the Paris Agreement. Last year’s summit ended with the introduction of the Glasgow Climate Pact which called for updated NDCs to be made within a year, in preparation for COP27, however very few countries have done so.

This year’s conference recognises that mitigation requires bold and immediate actions and raising ambition from all parties, in particular those who are in a position to do so and those who can lead by example. COP27 hopes that a draft decision on the work programme for urgently scaling up mitigation ambition and implementation by 2030 can be reached.

Adaption

Extreme weather such as heatwaves, floods and forest fires have become an everyday reality for some countries. The ‘Global Goal on Adaptation’ was one of the significant outcomes of COP26, and one goal of this year’s summit is to make further progress towards enhancing resilience and assisting the most vulnerable communities.

Beyond the Global Goal on Adaptation, COP27 aims for an enhanced global agenda for action on adaptation, confirming what was agreed on in Paris and further elaborated on in the Glasgow pact, with regard to placing adaptation at the forefront of global action.

Finance

COP27 aims to make significant progress on the crucial issue of climate finance while moving forward on all finance related items on the agenda. Existing commitments and pledges, announced from Copenhagen and Cancún, through Paris and all the way to Glasgow, require follow up in order to provide clarity as to where we are, and what more needs to be done.

Progress on delivery of the annual $100 billion will build more trust between developed and developing countries, showing that actual commitments are being fulfilled – we hope to see COP27 encourage developed countries to deliver on these historic promises.

Global stocktake

The global stocktake process began at COP26 last year and its aim is to assess progress towards the Paris Agreement’s goal to limit global warming. This two-year process concludes next year at COP28 and the output of the global stocktake should serve as a basis for improved climate ambition. Technical expert discussions on the inputs and outputs of the global stocktake are set to continue at COP27.

The summit has the power to set the course for the future of the green economy. Given the individual national pledges, financial commitments and frequent performance reviews, we expect governments to translate these measures into local policies, trade-offs and grants available to businesses, resulting in a significant increase in sustainable and green inventions. All solutions and innovative concepts helping to fulfil the green agenda and mitigate climate change should be protected, and the best way to do so is with help of intellectual property rights.

Mathys & Squire works with numerous clean-tech clients on green technology breakthroughs and sustainable solutions. We are honoured to partner with companies and inventors who are addressing climate change and whose initiatives further the objectives set forth by COP27.

We eagerly await the results of the COP27 summit to see how they will influence future generations of green technologies.

In honour of the spooky season, we are exploring tales of IP terror for patent and trade mark attorneys. Now is the time to check your closet and cover your eyes, as we take you on a walk through the graveyard of IP despair, and discover what horrors wait for you on the other side of IP law.

Weak trade marks – a scary sight for trade mark attorneys

A trade mark’s essential function is to designate brand origin. This means that it must be capable of distinguishing the goods/services of one undertaking from those offered by other undertakings. Often it is tempting to choose a brand name that ‘sends a message’ about the business; from a marketing perspective, this may even be desirable. However, many brand owners risk falling into the descriptiveness/non-distinctiveness spooky trap. That is, adopting a trade mark that is not capable of protection, and not enforceable.

As trade mark attorneys, we see it time and again. Brand owners will be refused protection for their marks and will struggle to stop third parties from using identical and/or similar names. Who are the main culprits? Usually, it’s purely descriptive words (such as ‘plus’, ‘extra’, ‘ultra’), words describing the business or the goods/services offered, buzzwords characteristic to each industry, and/or combinations thereof.

For example, with the recent sustainability movement, terms such as ‘BIO’, ‘ECO’, ‘GREEN’ and ‘ENVIRO’ have become increasingly popular. Sadly, they are also unenforceable. Accordingly, trade marks such as ‘Bio Cup’, ‘Bio Organics’ and ‘Clean & Green’ have been refused protection. Avoid the pitfalls of descriptive/non-distinctive marks and check with a trade mark attorney whether or not your chosen name is capable of protection.

Patent ownership – keeping skeletons out of your closet

As a patent attorney, I would much rather see someone tricked with silly string on their front lawn than be faced with an ownership scenario gone wrong! Although inventions are devised by inventors, the actual legal owner of a patent application is the ‘applicant’ (later ‘patentee’ once grant is reached) which is typically a business entity employing the inventor(s). In many territories, including the UK, transfer of relevant IP rights from employee to employer is covered under statutory provisions. However, this does not mean that disputes can’t arise, or other situations in which case-specific demonstration of chain-of-title is required.

To be in a position to address future queries or confusion regarding ownership that may arise, it is always sensible to formalise the relevant chain-of-title via assignment documentation, and it is best to do this as early as possible in the process, in case the inventors move on, disbursing like ghouls in the night.

Further complications can arise where (e.g. third party) collaborators are involved, such as: other companies, subsidiaries of a company, a commissioned party, or ‘non-employee’ inventors such as PhD students. Any one the above may have a claim to (partial) ownership and thus, such scenarios should always be investigated and dealt with.

Not policing a trade mark – the nightmare that keeps on giving

Obtaining trade mark registration for your brand and proudly displaying the ® symbol next to it is great. Not policing your trade mark and allowing identical or similar marks on the register – not so great. Business owners will successfully protect their branding by registering the important elements of it as trade marks but will take a passive approach to enforcing them. This can have its own dangers, as seen below:

Competitors creating confusion on the market, loss of trade and damage to reputation

If a brand owner A started a business and registered the brand name and then brand owner B also enters the market with an identical/similar name, consumers may buy from B erroneously believing the products originate from A. This will divert trade from A and result in a loss of profit. Zoinks!

Things can turn even uglier if brand owner B offers products or services of a lower quality than A, as this could adversely impact A’s reputation. Indeed, consumers may be dissatisfied with the service provided by B and attribute the bad experience to A, not being able to clearly distinguish between the two brands. A howling shortcoming, if you ask us!

Lessening of one’s trade mark rights

Furthermore, allowing trade marks on the market and/on the register that are similar to brand owner A’s mark will result in its weakening. Oh-oh! Brand owner B would then be able to argue that A’s mark has low distinctive character (and is more difficult to enforce) since several similar trade marks co-exist without confusion among consumers. Conversely, we note that there is only one ‘Apple’ in the information technology sector, which is unlikely coincidental. If several businesses were allowed to adopt ‘Apple’-derivative names for the same goods and services, the brand would have lost its significance.

Defence to infringement available to third parties

Finally, if brand owner A decides to stop brand owner B from damaging its business and tries to issue infringement proceedings, but brand owner B registered the similar mark in the meantime, B will now have a defence to infringement. This will create an additional hurdle for A, which could have been easily avoided by proper policing. The simplest way to protect against similar marks creeping on one’s business is monitoring the market and setting up a watching service – a literal guardian watching the registers and informing brand owners of any potential dangers.

Prior disclosure – a fright for any patent attorney

There are not many scenarios patent attorneys dread, but one of the most horrifying ones involve invention disclosures prior to patent filing. Picture the chilling scene where a client finds out their invention they have worked on so hard is not patentable anymore because they previously exposed its intricacies to the public. A true nightmare for any attorney – with no application officially filed and the invention now publicly disclosed, the chances of gaining successful IP protection may well have just vanished like a ghost in the night.

Disclosing details of an invention prior to filing a patent application in such a way that the notional skilled person can now recreate it, would prejudice the novelty of an associated patent claim, a key requirement to be patentable. Although so-called ‘grace periods’ exist in certain territories – providing a period of typically 6-12 months prior to filing in which an inventor can disclose without destroying patent novelty – such generic grace periods do not apply at the UK or European Patent Offices.

But fear not, there is a means to hold steadfast against a complete loss of IP protection, as the registered design system does enjoy such grace period. Registered designs offer an alternative to protect certain features of your product, even after disclosure, as long as the disclosure did not occur more than 12 months prior to filing. Although the prior disclosure may render pursuing patent protection untenable, design features (e.g. the appearance) of a product can still be protected. This means any IP vampires wanting to leach off your hard work will struggle to recreate the look of your exact design without facing the wrath of a vengeful design attorney.

Luckily, we have encountered these terrors so you do not have to worry! Follow our advice and you will be safe from the IP ghouls and ghosts aiming to halt and hinder your progress. If in doubt, always reach out to an experienced attorney for advice.

The UK Government has published its annual report on the work of the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) and the role it plays in driving innovation and growth in the UK. In particular, the report identifies the UK as a leading innovator in key areas of green technology and outlines ongoing developments to the UK IP system.

The benefit of IP for the UK economy is clear – with investments in intangible assets now exceeding total tangible investments, the IPO estimates that industries with above average use of IP rights accounted for 15.5% of total UK employment and over half (£159.7bn) of all exported goods in the last year.

The Innovation and Growth Report 2021-22 sets out how the work of the UK IPO has promoted innovation and productivity within the UK and how it supports the UK’s position as a ‘global science superpower’. In particular, their strategy is characterised by two outward facing pillars: delivering excellent IP services and creating a world leading IP environment.

Core IP services

There is an ever-increasing volume of IP activity in the UK, with the last year seeing record numbers of trade mark and design applications (up on the previous year by 16.1% and 71.8% respectively) and the highest number of granted patents in over 30 years. The IPO has also cleared Covid-induced backlogs and examination times for its core IP services. A funding support scheme was launched to help innovative SMEs recover from the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as an IP audits scheme helping businesses fund professional audits of their IP assets.

The IPO has also made progress with the ‘One IPO transformation programme’ for streamlining IP services, with the opening of an integrated digital renewals service for all registered IP rights. They have also developed prototypes for ‘manage IP’ (IP management service) and ‘secure IP’ (digital IP application service) and have performed initial work for ‘research IP’ (searching and analysis tool for UK IP rights) and ‘challenge IP’ (digital hearings and tribunals service). The rollout of these four services under the ‘One IPO’ umbrella can be expected in 2023.

World leading IP environment

The second pillar of the IPO’s strategy is about developing IP policy frameworks for the UK, both domestically and internationally, emphasising the importance of securing post-Brexit trade deals. IP provisions in recent trade deals include a commitment from New Zealand to adopt a reciprocal right to compensation for visual artists, and an agreement from Australia to make reasonable efforts to accede to the Hague agreement on industrial designs. In addition, an innovation collaboration has been agreed with Switzerland and negotiations are underway with India, Canada and Mexico.

Looking ahead, the report identifies several ongoing research projects commissioned by the IPO to create a sustainable, innovative and world leading IP environment. These projects include developing trackers for copyright infringement and counterfeit goods, researching the use of trade secrets in SME communities, and exploring key areas of technology for the future, including metaverse/extended reality technologies, blockchain/NFTs, artificial intelligence (AI) and ‘green’ technologies. There has been a significant increase in worldwide patenting activity for renewable energy and green vehicle technologies (more than doubling in the last five years), with the UK ranked as the top patenting country for offshore wind power and green building technologies. Further analysis on green technologies is due later this financial year from the IPO’s green technologies working group.

Following the consultation on how to handle AI within the patent and copyright systems, the government’s response was published earlier this year, and the IPO has conducted various studies, including on the use of IP to incentivise investment in AI, and the use of AI to enforce IP rights. In September, they also released guidance for patenting AI inventions in the UK.

IP enforcement has also been a major area of work for the IPO, having published their new counter-infringement strategy in February and increasing intelligence capabilities and coordination with law enforcement.

We are pleased to see the ongoing success of the UK IP system and look forward to the upcoming developments and publications from the IPO.

Data and commentary provided by Mathys & Squire, as published in Legal Week, provides an update on the appointment of Unified Patent Court judges.

An extended version of the press release is available below.

The Unified Patent Court – Europe’s new single point of contact for patent enforcement – took a major step forward with the confirmation that 85 of its judges from across the EU have now accepted positions on the court.

Mathys & Squire, the leading intellectual property law firm, says that after years of delay, the Unified Patent Court is now fast approaching and that patent holders worldwide cannot afford to ignore it.

The UPC confirmed the appointment of 85 judges on the evening of October 19 after receiving over 1,000 initial applications for the positions. Mathys & Squire says that the nationalities of the judges reflect where the ‘hotspots’ of patent litigation are in Europe, and where the pool of potential judges is largest. Of the 85 judges appointed, the countries with the greatest representation are:

• Germany 27

• France 17

• Italy 11

• Netherlands 7

• Belgium 5

• Denmark 4

• Finland 4

• Sweden 4

A further judge has both French and German nationality. Austria, Bulgaria, Estonia, Portugal and Slovenia are each represented by a single judge. Three more judges remain to be appointed before the commencement of the court’s operations – one each in Paris, Munich and Copenhagen. Four of the countries participating in the UPC (Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Malta) are not represented by any judges. Other EU countries are not represented as they have not yet agreed to participate in the UPC. Ireland is holding a referendum to decide whether to join the court, which is expected to take place in 2023 or 2024.

Under the UPC, patent holders can enforce a European patent across all participating countries through a single litigation procedure under the regime of the UPC. Estimated costs for such a claim will be slightly higher than litigating in one single country, but the UPC will be able to grant supranational injunctions as well as damages.

Businesses that anticipate having to defend their IP may wish to opt out of having their current intellectual property covered by the UPC. Opting out will prevent competitors from ‘knocking out’ their patent across Europe in a single judgement in the UPC.

The UPC was discussed for a long time and first agreed in 2013 but was held up for years by the domestic ratification processes of the member states. With the appointment of judges, the long-awaited court has cleared one major hurdle on the road to becoming fully operational.

Andreas Wietzke, Partner at Mathys & Squire says: “With the successful appointment of judges, one major obstacle to the operation of the UPC across the EU has been overcome. These judges will play a key role in setting early UPC precedents and determining the future of intellectual property enforcement in Europe.”

“The new court will provide a simplified and cost-efficient patent litigation system for anyone holding a European patent.”

“Businesses with patents pending or granted in Europe can no longer afford to ignore the UPC. They need to ensure they have the right strategy in place to protect their IP and the value of their business.”

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the 2022 Nobel Prize in the field of Chemistry to K. Barry Sharpless at the Scripps Research Institute, Morten Meldal at the University of Copenhagen, and Carolyn R. Bertozzi at Stanford University, for their roles in the development of click chemistry and bioorthogonal chemistry.

In his paper entitled ‘Click Chemistry: Diverse Chemical Function from a Few Good Reactions’, Sharpless noted that traditional means of reconstructing complex molecules found in nature required the use of complex multi-step reactions which were considered to be less efficient and resulted in the formation of considerable amounts of unwanted byproducts. Sharpless proposed a new approach to the synthesis of complex organic structures aimed at accelerating the rate at which new compositions could be formed. With regards to this new synthetic approach, Sharpless noted “The approach derives from a keen awareness of natures preferred methods of synthesis, but does not seek to emulate them too closely. Nature is a matchless creator of C-C linkages and we propose leaving the tough job of C-C bond synthesis as much as possible to her.” The new method of synthesising complex molecules, referred to as ‘click-chemistry’, was based on a process of forming of heteroatom bridges (C-X-C) between molecular building blocks containing the required carbon structure.

Sharpless stipulated that in order to fall under the term ‘click chemistry’, a reaction must “be modular, wide in scope, give very high yields, generate only inoffensive byproducts that can be removed by nonchromatographic methods, and be stereospecific (but not necessarily enantioselective). The required process characteristics include simple reaction conditions (ideally, the process should be insensitive to oxygen and water), readily available starting materials and reagents, the use of no solvent or a solvent that is benign (such as water) or easily removed, and simple product isolation.”

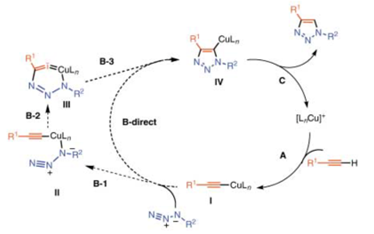

The ‘click chemistry’ process was further developed when Morten Meldal and Barry Sharpless both independently developed a copper catalysed azide-alkylene cycloaddition reaction, in which one reactant comprises an azide functional group and the other an alkylene functional group. In the presence of a copper (I) catalyst the two reactants form a triazole structure (as shown below). By incorporating these azide/alkylene functional groups, different building blocks may be reacted precisely and efficiently allowing researchers to synthesise more complex organic structures.

Proposed catalytic cycle for the Cu1-catalysed ligation, taken from “A Stepwise Huisgen Cycloaddition Process: Copper(I)-Catalyzed Regioselective “Ligation” of Azides and Terminal Alkynes” Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 2002, 41 No. 14.

Bertozzi further developed the ‘click chemistry’ process for the purpose of studying glycans on the surface of cells. Previously, it had not been possible to study glycans, sugar-based polymers which play a vital role in our immune responses, on living cells. The bioorthogonol reactions developed by Bertozzi replaced the copper catalyst previously used – which is toxic to organic cells – with cyclooctyne, an 8-membered alkyne ring. Bertozzi discovered that the strain energy within such compounds could be used to drive the ‘click chemistry’ process in the absence a copper catalyst and without disrupting the normal chemistry of the cell.

This research has made a considerable contribution to humankind as it has enabled new drugs and pharmaceutical compositions to be discovered in shorter time periods. New research into cancer treatment has been based on this development. In particular, studies developing clickable antibodies which target different tumours are ongoing.

UPDATE as of 19 October 2023

The European Patent Office (EPO)’s ‘10-day rule’ will cease to exist from 1 November 2023. From that date, EPO communications will be deemed to be delivered on the same date which they show, rather than 10 days later (as occurs at present). Click here to find out more.

As of yesterday, 13 October, the Administrative Council of the European Patent Office (EPO) has passed “a new package of rule changes intended to adapt the rules of the European Patent Court (EPC) to the digital age”, according to a report from the UK’s Chartered Institute of Patent Attorneys (CIPA). One rule due to change as part of this package is Rule 126(2) EPC, also known as the ’10-day rule’. This will affect the majority of deadlines in proceedings before the EPO.

Users of the European patent system will be familiar with the EPO’s ’10-day rule’. For those unaware, it is a legal fiction that states official communications from the EPO are typically said to have been delivered to the recipient 10 days after the date which they bear. Many deadlines at the EPO are calculated based on the ‘deemed’ delivery date of official EPO communications. From November 2023, EPO communications will be deemed to be delivered on the same date which they show, rather than 10 days later as they are at the moment. This means that from November next year many deadlines set by the EPO will be 10 days shorter than they are at present.

Abolition of the 10-day rule had been proposed earlier this year but the EPO opted not to go ahead with the rule change at that time. Although the EPO has not officially confirmed CIPA’s report at the time of writing, it looks as though a rule change has now formally been agreed.

It is important to note this new rule will not come in to force until 1 November 2023, providing time for users to adapt their docketing systems appropriately. According to CIPA, the EPO will additionally run a publicity campaign over this coming year to assist those concerned in dealing with the coming rule change.

More details of the planned rule change will follow when we receive them, including confirmation of any transitional measures (e.g. for communications issued before the rule change comes into force) as well as confirmation of safeguards which we understand will be put in place in case documents are not delivered on time.