Last month, Amazon released their Brand Protection Report for 2022. Claiming to have invested over $1.2 billion and devoting 15,000 personnel to their brand protection initiatives, we look at some of the statistics and measures highlighting Amazon’s ongoing efforts to scale intellectual property (IP) protection and tackle the problem of counterfeits.

Robust proactive controls

Reportedly scanning over eight billion listings daily, Amazon states that controls such as seller verification and continuous monitoring have reduced the number of ‘bad actor’ attempts to create new selling accounts by more than 50%, year on year.

This will be reassuring for brands knowing that these measures have meant that apparently 99% of listings are proactively removed when suspected of being fraudulent, infringing or counterfeit.

Powerful tools to protect brands

Launched in 2017, Amazon’s Brand Registry provides brands with various automated protections to ensure their IP rights are protected. Amazon reports that these measures have seen a reduction of over 35% in the number of infringement notices submitted by brands compared to 2021.

Amazon also collaborates with the United States Patent and Trademark Office, working to ensure fraudulent applications and registrations are not used to enrol in its Brand Registry. They report that the partnership to date has identified and blocked over 5,000 false or abusive brands from enrolling in the Brand Registry.

Patent holders can also benefit from the Amazon Patent Evaluation Express, which allows neutral evaluation of a potentially infringing product in less time than a traditional lawsuit.

Holding bad actors to account

Amazon’s global Counterfeit Crimes Unit has reportedly succeeded in removing over six million counterfeit products from the global supply chain, claiming more than 1,300 criminals have been pursued through litigation and criminal referrals.

Protecting and educating customers

Partnerships with bodies such as the US Chamber of Commerce and the International Trademark Association show Amazon’s continued commitment to limit the reach of counterfeit goods and educate consumers.

Many brand owners will be keen to register their trade marks on the Brand Registry. Depending on the territory in which the trade mark is protected, brand owners would require either a pending application or registration in order to utilise the Brand Registry.

The Mathys & Squire team is happy to assist clients in filing trade mark applications and obtaining trade mark registrations for this purpose.

Data and commentary provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in articles by Environment Journal and The Patent Lawyer providing an update on the decline in Green Channel patent applications.

An extended version of the press release is available below.

The number of Green Channel patent applications in the UK has fallen by 47% within the last year, decreasing from 313 applications in 2021* to 166 applications in 2022*, says intellectual property law firm Mathys & Squire.

The Intellectual Property Office’s Green Channel was introduced in 2009 to encourage the development of more environmentally friendly technology by providing a quicker route for the patenting of that technology. It allows inventors of eco-friendly products to bypass the years’ long wait and obtain patents two to three times faster than they otherwise would.

The decline in the number of Green Channel applications may be because the benefits offered by the scheme aren’t enough of an incentive for smaller companies.

Posy Drywood, Partner at Mathys & Squire says that a better way of encouraging the development and patenting of green technology would be for the UK Government to pay for fees due to the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) for green patents.

Patent applications submitted through the IPO’s current Green Channel are fast-tracked through the evaluation process. However, the sooner a patent is approved, the sooner patent fees are due.

The Green Channel’s accelerated processing means that applicants have less time to gather the necessary funds, which isn’t always ideal for small businesses that may struggle to pay. In this way, speeding up the patent process could discourage small businesses from using the Green Channel.

Posy Drywood adds: “If we want to see a substantial increase in green technology created by the UK, just speeding up the patent application process is not going to cut it. Small businesses need more than that to make using the Green Channel worthwhile. As green technology is so important to the growth of the UK economy, subsidising green patent applications should be considered.”

“While fast-tracking the application process is a benefit, it also speeds up the time in which applicants have to pay their patent fees. That may be a deterrent to small businesses, especially as we enter into a period of economic uncertainty.”

“In its current state, the Green Channel isn’t working as effectively as it could do to promote more green technology. A better way to encourage greater IP production is to make patenting those products more affordable.”

*Year-end December 31

Owners of retained EU plant variety rights (PVRs) need to take action by 1 January 2024 in order to maintain these rights.

As was widely reported at the time, Brexit affected the protection afforded by various types of community intellectual property, including community plant variety rights (CPVRs).

Applicants with pending CPVR applications have already had to take action to convert their applications into corresponding UK plant breeders’ rights (PBRs).

However, holders of granted CPVRs have not, to-date, needed to take any action, as all varieties granted a CPVR by the end of the Brexit transition period were automatically given protection via a corresponding right under UK legislation. These are referred to by the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) as ‘retained EU PVRs’, and will have the same duration of protection as that remaining for the granted CPVR.

This automatic creation of retained EU PVRs has generated a massive number of new entries (>30,000) in the UK’s Variety Tracking System (VTS) database that require significant administration and management by APHA.

To assist in the management of these retained EU PVRs, APHA has announced that holders of such rights will need to proactively confirm that they wish to retain these rights.

In particular, the holders of retained EU PVRs need to provide APHA with:

- confirmation that they are the correct holder of the retained EU PVR;

- an express indication of which of their retained EU PVRs are to be maintained or surrendered (this information can be provided by completing Annex 1, which has been compiled by APHA and lists all retained EU PVRs, and has been provided by APHA to all rights holders);

- an address for service in the UK or the name and address of an agent within the UK (provided via a completed Authorisation of Agent (PVS11) form); and

- any changes to the details of the rights holder should be recorded on a completed APHA Assignments of Rights form (PVS10), together with a copy of the Community Plant Variety Office register excerpt showing that the EU holder of the rights has changed.

Once this information has been provided to APHA, the VTS will generate a UK grant number for each retained EU PVR, and this will be published in the Seed Gazette.

APHA has indicated that this information should be provided by 1 January 2024. After this date, the controller may formally request a UK address for service or a UK agent. If the information is still not provided for a given retained EU PVR, APHA may terminate said right if satisfied that the holder of the rights has failed to comply with a request under regulation 6 of the Plant Breeders’ Rights (Amendment etc) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019.

In view of the large number of retained EU PVRs that need to be migrated to the VTS, APHA is strongly advising holders of retained EU PVRs to provide the requested information well in advance of 1 January 2024.

If you need any assistance regarding confirming maintenance of your retained EU PVRs, please contact the author, or your usual Mathys contact.

As the Unified Patent Court (UPC) launch date approaches, the question on everyone’s mind regarding the placement of the third branch of the central division has finally been answered. Following Brexit and the UK’s subsequent withdrawal of its ratification of the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court, the UPC had to find a new location to host the central division’s third branch, which had originally been allocated to London.

After years of speculation and only two weeks before the official launch, the UPC has finally provided an update, although maybe not one that was widely anticipated. During a meeting on 8 May 2023, the Presidium of the UPC decided that any actions relating to patents in IPC section A (Human Necessities) will be assigned to the seat in Paris, and those relating to patents in IPC section C (Chemistry) will be assigned to the Munich branch.

Despite previous reports of Milan being all but confirmed as the third location, it has also been rumoured that the Italian, German and French governments are yet to agree on a division of technical classes between the three branches of the court. Given the Presidium’s characterisation of the reallocation of competencies to Paris and Munich as being “provisional”, it seems that negotiations in this respect may still be ongoing even as time runs out on the sunrise period.

As we anticipate the opening of the UPC’s doors on 1 June 2023, we will report on any updates that are released and will continue to support our clients and contacts on their UPC journey.

With two locations in Hertfordshire, Fabio’s Gelato is a family-owned gelato producer and dessert parlour. On 2 May 2023, Fabio’s Gelato posted an announcement of a new gelato flavour, ‘Perky Pig’, coming to its Letchworth parlour. Marks & Spencer (M&S) caught wind of this quickly and sent a letter, dated 5 May 2023, addressing the potentially infringing name of the new flavour.

‘Percy Pig’ – a hero brand

The letter politely explains that ‘Percy Pig’ is one of M&S’s hero brands and they own registered trade marks to protect it. M&S asked Fabio’s Gelato to change the name of the ice cream within 14 days of receiving the letter to resolve the matter “amicably” whilst even suggesting a few potential alternatives. However, M&S also made it clear that it was happy for Fabio’s Gelato to continue using the famous sweets to top the ice cream. Fabio’s Gelato took to social media to share the letter, along with a bag of ‘Percy Pig’ sweets that M&S had sent to “sweeten the deal.”

Rebrand to ‘Notorious P.I.G‘

Provisionally renamed as ‘Fabio’s Pig’, the news gave Fabio’s Gelato so much media exposure that it was decided to host a competition for its Facebook followers to come up with a new name, promising a Fabio’s voucher for the winner. With over 100 entries, the winning name was ‘Notorious P.I.G.’

Small businesses and trade mark infringement

The swift response highlights how important the ‘Percy Pig’ brand is to M&S, acting within three days to prevent any potential brand dilution. However, the way M&S dealt with the situation has received praise, showing an understanding that a smaller business may simply not be aware that their products could infringe other brands’ intellectual property rights.

M&S has shown that matters of trade mark infringement can be solved quickly and amiably between the parties involved. There are benefits of a gentler approach and methods of dispute resolution available to maintain everyone’s best interests. It has even resulted in some good publicity for both parties, showing that a positive approach can result in the best outcome all round.

As for the new ‘Notorious P.I.G.’ ice cream – Fabio’s Gelato is“frantically making more!”

The UK Government has appointed seven high-profile science and technology leaders to the new Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) Startup Board. These non-executive directors include the likes of astronaut Tim Peake, McLaren founder Ron Dennis, Professor of natural sciences Jason Chin (Trinity College, Cambridge), and Shonnel Malani, Managing Partner at Advent International, who will serve as lead non-executive board member.

The DSIT was established in February with a mission to cement the UK’s position as a science and technology superpower by 2030. Since then, it has announced funding of hundreds of millions of pounds for innovation accelerators, continued research into the field of life sciences and the development of laboratories, and has published strategies for growth in the artificial intelligence, quantum, and wireless infrastructure sectors.

The newly appointed non-executive board members will provide strategic guidance and insight as the department focuses on driving economic growth, creating jobs, and improving the lives of citizens through science, technology, and innovation. They will serve for nine months on an initial startup board that will nurture DSIT through its first year of existence, before a permanent board is recruited in due course.

Science and technology Secretary Michelle Donelan expressed the government’s commitment to incorporating the best and brightest minds from the science and tech worlds at every level of decision making in the government. The success of the DSIT, according to Donelan, will play a crucial role in delivering long-term economic growth, which is a priority for the UK Government.

In response to his appointment to the board, astronaut Tim Peake said that “As a former test pilot and astronaut, who has taken part in more than 250 scientific experiments for the European Space Agency and international partners, I hope to bring a wealth of experience of how science, technology and innovation are critical to both learning and development.”

The appointment of these high-profile figures to the DSIT Startup Board demonstrates the UK Government’s determination to advance the country’s science and technology leadership and agenda. It is also an opportunity for the private and public sectors to collaborate on innovative areas that will transform lives and drive economic growth across the country.

The appointment of these non-executive directors brings a wealth of experience and expertise to the DSIT, furthering the department’s ability to achieve its goal of making the UK a science and technology superpower in the coming years.

The European Commission published their proposals for new regulations on standards essential patents (SEPs), compulsory licensing of patents in crisis situations, and revised legislation on supplementary protection certificates (SPCs). These proposals, implemented by the European Commission, will only directly affect the European Union (EU) and not the UK.

Proposed regulations on standards essential patents

Of all of these proposals, the proposed new regulation on SEPs is perhaps the most contentious, having been leaked on 24 March 2023. This was commented on widely in the press and among the global patent community, including in a letter by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI), a post by IP Europe, and a post on LinkedIn by Fabian Gonell, Chief Licensing Lawyer at Qualcomm, who went so far as to say that the “draft regulation would upend patent rights in Europe and have a host of unintended consequences.” By contrast, Apple (an implementer) has been very active in lobbying for the current version of the draft regulation. Commentators have noted that is because the draft regulation would be pro-licensee and anti-patentee, and might well encourage ‘hold-out’ behaviour where an unwilling licensee could delay enforcement.

The proposals include assigning to the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), which currently administers community trade marks and community designs but does not yet have any patent expertise, the task of building an SEP register and a procedure for determining FRAND rates for SEPs. This also includes the option for regular checks (instigated by either implementer or SEP owner) to determine whether a sample of up to 100 patents are indeed essential – although the results of this are not legally binding. However, ETSI noted in their letter that they already maintain their own database of essentiality declarations and also technical specifications. The proposed regulations also impose an obligation on bodies such as ETSI to provide certain information to EUIPO which would place a significant burden on them, in particular relating to known implementations of the standard, which ETSI have said even they do not have the tools or resources to comply with.

With regards to determining FRAND rates for SEPs, this can be initiated upon request by an implementer or SEP owner and is to be completed within nine months and facilitated by ‘conciliators’ which shall be chosen by the parties from a group proposed by the EUIPO. However, commentators have questioned whether any imposed FRAND rate determination by two ‘conciliators’ (and without appeals available) at the EUIPO, an institution that until now has never dealt with patents before, resulting in a non-binding result in a very short timeframe, would work in practice, as it will unlikely be respected in the market.

IP Europe noted that the proposed new regulation is damaging for:

- departing radically from existing precedent, without sufficient data;

- turning over management of SEPs to an agency with no previous experience with patents or standards;

- creating an unpredictable and unbalanced system which will further delay licence negotiations and royalty payments, potentially for many years;

- ignoring the EU’s commitments under the World Trade Organisation’s TRIPS Agreement and TBT Agreement, and the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights to defend patent rights; and

- imposing an artificial and premature cap on aggregate royalties for implementations of a standard with a process that is open to misuse.

Compulsory licensing

The Commission notes that the new rules foresee a new EU-wide compulsory licensing instrument that would complement EU crisis instruments, such as the Single Market Emergency Instrument, HERA regulations and the Chips Act. The Commission states that in light of the COVID-19 crisis, these new rules would further enhance the EU’s resilience to crises, by ensuring access to key patented products and technologies, should voluntary agreements not be available or adequate.

Supplementary protection certificates

The proposal also introduces a unitary SPC to complement the Unitary Patent, along with a centralised examination procedure to be implemented by the EUIPO.

2023 EU SME fund

Concurrently with the proposal, the 2023 SME fund was also announced making vouchers available for SMEs to save up to €1,500 on their patent registration costs.

The European Commission’s proposals for new regulations on SEPs, compulsory licensing of patents in crisis situations, and revised legislation on SPCs have stirred up a lot of debate and commentary within the global patent community. While some, such as Apple, have actively lobbied for the proposed changes, others have expressed concerns about the potential unintended consequences of the regulations, particularly the new regulation on SEPs.

Nevertheless, the Commission argues that these new rules would boost innovation and investment within the EU, enhance the region’s resilience to crises, and support SMEs through the 2023 SME fund. It remains to be seen how these proposed regulations will be received and implemented within the EU and beyond.

The dispute began in 2022 when Lidl launched proceedings against Tesco, alleging that Tesco’s use of its ‘Clubcard Prices’ sign (Fig. 1 – yellow circle in a blue square with the words “Clubcard Prices” in the middle) amounted to trade mark and copyright infringement of its own Lidl mark (Fig. 1 – yellow circle, surrounded by a red ring in a blue square containing the word “Lidl” ) as well as its registration for the same design but without any text (the wordless mark).

Both marks comprise a yellow circle on a blue square, used by Tesco since September 2020 to advertise its Clubcard Prices loyalty discount scheme and indicate which products are eligible, and by Lidl in its main logo.

Lidl alleged that Tesco’s use of the yellow circle against a blue square was intended to deliberately take advantage of Lidl’s reputation as a discount supermarket and that consumers are likely to believe that Tesco’s mark is Lidl’s. Essentially, Tesco is “seeking deliberately to ride on the coat tails of Lidl’s reputation as a ‘discounter’ supermarket known for the provision of value.”

Tesco filed a counterclaim, arguing that:

- Lidl has never made genuine use if its wordless mark and that the registration should be revoked or declared invalid based on non-use.

- Lidl’s application to register the mark was filed in bad faith.

Drawing on arguments from Sky v SkyKick, Tesco alleged that the wordless mark was registered by Lidl as a legal weapon, a product of its trade mark filing strategy. There was, Tesco claimed, no intention by Lidl to use the mark in commerce, only to widen its legal monopoly right.

Tesco also accused Lidl of ‘evergreening’ by filing successive trade mark applications periodically for the wordless mark in 2002, 2005, 2007 and 2021 in order to refresh the grace period and avoid having to prove genuine use, drawing arguments from Hasbro Inc v EUIPO.

Lidl made an interim application to the Court to strike out Tesco’s counterclaim that some of Lidl’s registrations should be invalidated for bad faith and for permission to rely at trial on survey evidence in relation to the distinctiveness of its trade marks. The High Court agreed with Lidl on both counts and claimed that Tesco had not produced sufficient evidence to rebut the presumption that Lidl’s application had been made in good faith. The court held that mere lack of intention to use the trade mark did not constitute bad faith and struck out Tesco’s bad faith counterclaims. Tesco appealed.

Tesco’s grounds of appeal

Tesco argued that the High Court had:

- Failed to apply the correct test to the striking out application under rule 3.4(2)(a) of the Civil Procedure Rules, and that it had also failed to consider that bad faith is a developing area of the law.

- Failed to consider all of the alleged facts and inferences in its bad faith counterclaims in the context of Lidl’s infringement case, considering that no disclosure had yet been given by Lidl as to its intentions when registering the wordless mark.

On this premise, the Court of Appeal granted the appeal.

Court of Appeal decision

While disagreeing with Tesco’s argument that the judge had applied the incorrect test, the Court of Appeal did agree that Smith J had neglected to consider bad faith as growing field of law and failed to properly consider the pleaded facts.

Tesco’s first claim alleged that the wordless mark (first registered in 1995) was applied for without any intention of using the mark, but instead as a way of securing a wider legal monopoly than afforded by the mark used by Lidl since 1987 and registered in 2011 as a mark with text. The Court relied on Ferrero SpA’s Trade Marks [2004] RPC 29 and Target Ventures Group Ltd v EUIPO case T-273/19. In both cases, the proprietors’ registrations of new marks, which were not intended to be used in the course of trade but instead designed solely to extend the scope of existing registrations amounted to bad faith. The Court of Appeal held that it was wrong for the High Court judge to say that Tesco’s allegations were “no more than assertion”, as all allegations must be assumed to be true unless shown to be manifestly unsustainable. Lidl could have presented evidence to show that this allegation was unsustainable but had not done so.

On Tesco’s second claim that the re-filing of the wordless mark amounted to ‘evergreening’ and should be declared invalid, it relied upon Hasbro Inc v EUIPO Case T-663/19, in which the General Court found that Hasbro had acted in bad faith by re-filing its ‘MONOPOLY’ mark to avoid having to provide proof of use. Tesco alleged that Lidl’s re-filing activity supported the bad faith claim.

The Court of Appeal reversed the High Court’s decision to strike out Tesco’s bad faith counterclaims and held that Tesco had raised “sufficient objective indicia to give rise to a real prospect of the presumption of good faith being overcome so as to shift the evidential burden to the applicant for registration to explain its intentions.” Tesco had substantiated its pleadings sufficiently.

Where are we now: back in the High Court and going round in circles

In addition to providing a reminder of the legislative and judicial context for the concept of bad faith, the Court of Appeal’s decision provides useful insight into two specific types of activity that may result in a finding of bad faith: filing for ‘defensive’ marks and ‘evergreening’ marks, as well as highlighting that the concept of bad faith is a developing area of UK law.

We return full circle and on 7 February, the trial began at the High Court which will now reconsider Lidl’s initial claims of trade mark infringement and Tesco’s counterclaims of non-use and bad faith. The case will provide further guidance on various issues, such as the threshold needed to be met in satisfying the bad faith criteria, the process of ‘evergreening’, and what is meant by lack of intention to use a mark. We may also expect guidance on the use of wordless marks as well as the relevance of survey evidence in establishing the distinctiveness of trade marks.

Given the highly anticipated Sky v SkyKick appeal to the Supreme Court in June this year, which will further investigate the notion of bad faith, we can expect to see additional clarity in this area of law and an opportunity to define the rules.

Just like its own mark, Lidl seems to be going round in circles; a discount retailer, well known for invoking recognised supermarket brands with its lookalikes, is now ironically claiming that consumers will think of Lidl when using their Tesco Clubcard. In the meantime, we will keep an eye on both cases as we anticipate the judgements.

The European Patent Office (EPO) has released its 2022 Patent Index, which evaluates trends in the number of European patent applications filed across different technical fields and geographical regions. In 2022, the EPO received a record 193,460 patent applications, representing a 2.5% growth from the previous year.

Increase in European patent applications from non-EPO states

While applications from EPO states remained the same, their overall share of filings fell to 43.4%, the lowest they have ever fallen. This is due to a surge in applications from China, South Korea and the United States. China saw the most dramatic increase in filings, with 15% more applications than last year, whilst South Korea has experienced a 10% growth rate.

Huawei was the leading patent applicant for its fourth year

Huawei continued its reign as the top patent applicant for the second year in a row and fourth year overall. Following Huawei were LG, Qualcomm, Samsung and Ericsson. With the increasing number of patent applications from China, the United States and South Korea, it is no surprise that these countries are where the top four applicants are based.

Another interesting trend that the Index revealed is that a significant share of applications from Europe were filed by SMEs or individual inventors, making up 20% of total filings.

Digital communication, medical technology and computer technology were the top technical fields

Digital communication was the top technical field for European patent applications, whilst also experiencing 11.2% growth from 2021. In fact, there has been a continuous increase in filings in this field since 2019. Medical technology and computer technology were the second and third technical fields respectively with the most patent filings. It is expected that these areas are likely to come together and play an important role in the future in respect of smart health innovation.

The technical field that saw the most growth was electrical machinery, apparatus and energy, with an 18.2% increase in patent applications. Another growing field was biotechnology, with an 11% rise in filings.

Sustainable innovation is the future

With many pledges towards carbon neutrality and investments in clean energy, sustainable innovation is becoming a focus for European patent applications. Patent filings regarding battery technologies have consistently been rising, whilst applications for fossil fuel technology patents have seen a decline. Sustainable innovation is accelerating and is anticipated to continue.

Looking ahead

It is apparent that the rate of innovation and subsequent patent filings are on the rise, with China, South Korea and the United States being partly responsible for the surge. The trends identified by EPO suggest that sustainable technologies are continuously on the rise, expecting an even more staggering increase in the years to come. What is pleasantly surprising to see is the high portion of applications are filed by SMEs, indicating that individual inventors are prioritising protecting their intellectual property. Through Mathys & Squire’s Scaleup Quarter, we cater to the burgeoning startup community and are proud to have worked on some of these applications with our inventive clients.

Data and commentary provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in articles by The Patent Lawyer, City AM, Carbon Pulse and Carbon News providing an update on the rapid growth in carbon capture patents applications.

An extended version of the press release is available below.

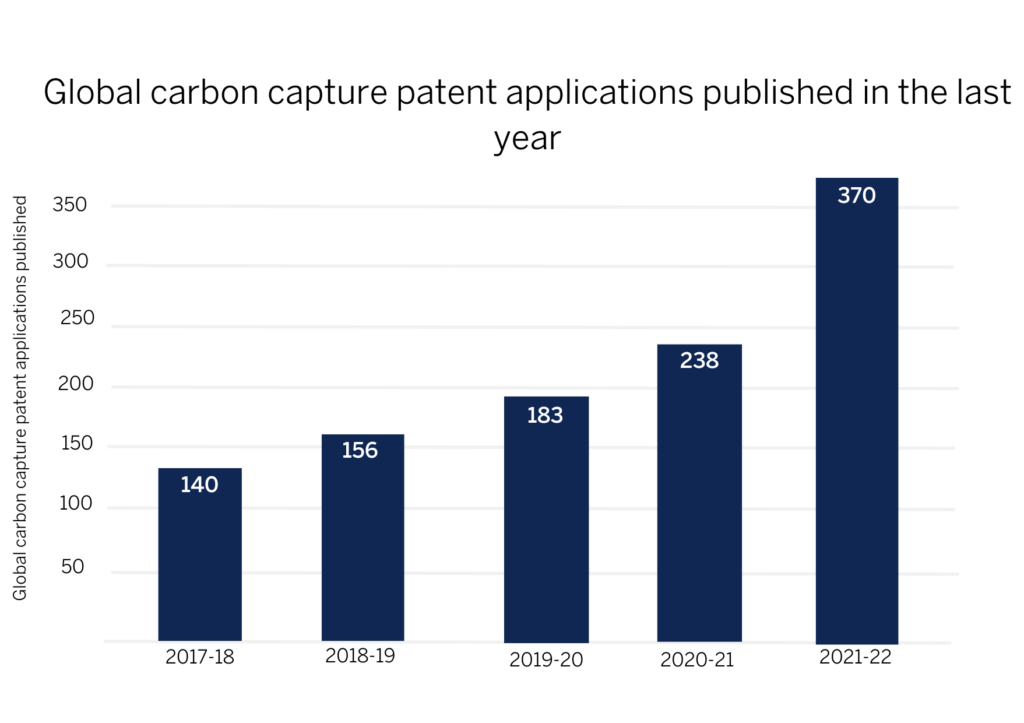

There have been a record 411 global patent applications for carbon capture and storage technology published in the past year*, up 65% from 249 in 2020/21, shows new research by Mathys & Squire, the leading intellectual property law firm.

Carbon capture and storage technology is generally regarded as a crucial tool in meeting CO2 emission targets, and companies are investing heavily in research and development in this area. Crucially, companies are seeking to patent technological breakthroughs to protect their IP and monetise their technology effectively.

While companies across a number of sectors have filed carbon capture patent applications, a key player is of course the energy sector, from which there have been 41 such patent applications published in the past year. Energy companies have identified carbon capture technology as a major tool in their strategies to reduce emissions. Notable filers of carbon capture patents include Exxonmobil, Saudi Aramco and Unilever.

Specialist carbon capture businesses, which have been established in recent years, were nevertheless responsible for 19 of the patent applications published in the last 12 months.

The United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has stressed the importance of carbon capture in reaching global net zero**. This has been reflected in many governments increasing investment in the technology.

The US Government announced $2.6 billion in funding for carbon capture projects in July 2022***, while in the same month the EU announced €1.8 billion in funding for clean technology projects for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, including carbon capture****.

A further example of governments encouraging investment in carbon capture technology is the recent discussions between the US and Indonesian Governments, leading to a $2.5bn carbon capture agreement between ExxonMobil and Indonesian state-owned energy company, Pertamina.

73% of published global carbon capture patent applications originated from China

In 2021-22, 73% of the carbon capture patent applications published (298) were from Chinese applicants – largely from energy companies and universities. The USA came second place with 10% (42), whilst the UK accounted for only five patent applications published, corresponding to just 1.2% of the global total.

China recently opened its largest carbon capture facility in Shandong province, with plans to build two more similarly sized plants announced*****. China aims to be carbon neutral by 2060 and the accelerated investment in carbon capture plants suggests the technology is a core part of its plans.

Innovative examples of recent patent applications related to carbon capture include:

- Carbon capture technology designed to be used in coal-fired power stations

- A method of producing diamonds from carbon captured from the air

- A carbon capture system designed for use in domestic households

Debate remains over whether resources and investment should be focussed only on renewable technologies, or on the development of other solutions in parallel. Some see carbon capture technologies as extending reliance on fossil fuels and hampering a shift to renewable technologies in the long term.

Michael Stott, Partner at Mathys & Squire, says: “Companies have recognised the commercial opportunity in mastering carbon capture technology, which is likely to form a key part of meeting the global net zero objective, and supplementing the progress that continues to be made in the advancement of renewable technologies.”

“Companies are racing to develop their carbon capture technologies and secure their IP. Those that can patent the most effective technologies are likely to have a commercial edge as the global economy transitions to net zero.”

“However, the UK lags behind other parts of the world in developing carbon capture technology. The UK Government may wish to consider whether current funding structures provide enough support to research and development in this vital field.”

“Support for carbon capture technologies doesn’t have to take away from renewables research. When it comes to achieving the global net zero objective, encouraging innovation across a broad range of technology areas can only be to the benefit of posterity.”

*Year end June 30 2022

**IPCC Special Report

***US Department of Energy

****European Commission

*****Sinopec