Videos published on the internet are an increasingly common source of technical information and are used by companies in the same way that marketing literature, user manuals, and educational content have been for some time.

The EPO’s register, and the manner in which evidence is submitted to the EPO, is generally not capable of either receiving video evidence other than by means of a URL.

If decisions of the EPO are to be subject to proper review on appeal, or are to be made properly available to the public, then this problem needs to be solved. The recent update to the EPO Guidelines went some way to address this issue for applications under Examination, but the question of how to deal with it in EPO Oppositions seems to remain open.

The 2023 update to the Guidelines (B-X-11.6 and G-VII-7.5.6) was related to a decision of a Technical Board of Appeal of the EPO in T 3000/19. In that case, the evidence cited by the Examining Division of the EPO in refusing an application was an internet video. The Examining Division cited the URL, gave a screenshot, and quoted some text from the video. They also cited certain video frames by reference to their time stamps. By the time of the appeal, the video in question was no longer available on the internet.

The Board found that the material available on the file “does not provide sufficient evidence to allow the Board to make its own assessment of the relevant evidence.” In explaining that this was unsatisfactory, the Board set out the requirements which should apply to such evidence by reference to the Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers to member states on electronic evidence in civil and administrative proceedings, a publication of the European Commission.

The Board commented that, such evidence “should be collected in an appropriate and secure manner, and submitted to courts using reliable services such as trust services” and using procedures established by member states for the secure seizure and collection of digital evidence.” They also made reference to the need to store such video evidence with standardised metadata and evidence demonstrating when and how it was made available to the public.

Parties wishing to rely on video evidence obtained from the internet, for example in Opposition Proceedings, clearly need to address these issues but the Guidelines do not say how. Opponents should consider creating a secure and verifiable archive of the evidence provided by an internet video disclosure.

They should also ensure that they have some means of verifying that the content of their archive matches the content of the internet video disclosure in case it is later changed or removed from the internet altogether.

According to an announcement this week from the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, agreement has officially been reached to situate a third branch of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) Central Division in Milan. The Milan branch of the Central Division is expected to open by June 2024. This will supplement the two branches in Paris and Munich which opened on 1 June 2023.

Originally the third branch of the UPC Central Division was destined for London, but after the UK withdrew from the UPC system in the wake of Brexit a decision was taken to relocate this branch. Milan has been rumoured to be the front-runner for several years, but negotiations seem to have been protracted. Notably, the announcement from the Italian government does not confirm which technical areas will fall within the competence of the new Milanese branch. London was originally to have competence for cases falling under IPC classifications A and C, relating broadly to chemistry, materials, life sciences and pharmaceuticals. For the time being these have been divided between Paris and Munich, and it is rumoured that those two branches might be seeking to hold on to some of that work even after Milan opens its doors. It is possible that discussions in that respect may be ongoing.

The Central Division of the UPC is the division with competence by default for actions concerning patent revocation and declarations of non-infringement. Other actions including infringement actions and applications for preliminary injunctions are, by default, the competence of the UPC’s Local and Regional Divisions. However, the Central Division has competence for these types of action in some circumstances, for example if the defendant is located in a country which is not party to the UPC Agreement, or if there is no local or regional division with competence to hear the case in the relevant UPC country/countries.

Each of Paris, Munich and Milan also already hosts a local division of the UPC, therefore the addition of a branch of the Central Division is likely to cement Milan’s position as a major venue for patent litigation under the new system.

Mathys & Squire is delighted to be ranked in the latest edition of the IAM Patent 1000: The World’s Leading Patent Professionals 2023 directory – the definitive ‘go-to’ resource for those seeking to identify world-class, private practice patent expertise. IAM undertakes exhaustive qualitative research, identifying top firms and individuals based on their depth of expertise, market presence and sophistication of work. Only those individuals who stand out for their exceptional skill sets and profound insights into patent matters feature in the IAM Patent 1000.

Aside from our firm ranking, 13 of our Mathys & Squire attorneys have been recognised as Recommended Individuals: Partners Paul Cozens, Martin MacLean, Alan MacDougall, Jane Clark, Chris Hamer, Andrew White, Dani Kramer, Anna Gregson, Craig Titmus, as well as James Pitchford. Additionally, Partners Stephen Garner, Juliet Redhouse and Michael Stott have been newly recommended in the guide.

Our attorneys have been praised as “proactive, responsive and accurate. Their communications are clear and easy to understand. The service they provide has been timely, accurate, helpful and courteous, and we have never had any issues with them. They have strong technical capabilities, and they make sure they have the right people doing the work. Their expertise, meticulous attention to detail, follow through and creativity always get positive results”. We are pleased that Mathys & Squire is recommended as “a top choice for prosecution across all manner of technical areas.”

The UK Government announced on 19 May 2023 its long-awaited national semiconductor strategy, setting out a 20-year plan to help secure and grow the UK’s world leading expertise in semiconductor technologies, whilst also strengthening resilience to supply chain disruption and protecting national security.

The national strategy recognises the importance of semiconductors to modern technologies of today and the future, and to the growth of the UK economy. The global semiconductor market, which was valued at $601.7 billion in 2022, is expected to grow by 6% to 8% a year up to 2030. The potential for growth in this industry is therefore huge and the government’s strategy is to bolster the UK’s position in the global semiconductor market by maintaining and building on its strengths.

The national strategy identifies the UK’s strategic and longstanding strengths in compound semiconductors, semiconductor chip design and intellectual property (IP), as well as world-leading research and development (R&D) supported by universities, which will play an important role in the development of new semiconductor technologies. Emphasis is placed on securing the UK an advantage in technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), high performance computers, quantum and cyber, to drive economic growth and future discoveries.

The strategy sets out a number of ambitious initiatives to help secure and grow the UK semiconductor industry, including a commitment to invest up to £1 billion in the sector over the next 10 years, with £200 million earmarked for the 2023-2025 period. The funding aims to, among other things, help deliver a new National Semiconductor Infrastructure Initiative and a specialist incubator pilot for semiconductor startups to improve access to infrastructure and facilities, as well as boost UK commercial innovation for SMEs to help make them seem more attractive to investors, and help new products get from lab to market faster than ever.

The strategy also involves a commitment to strengthen existing collaborations with international partners, such as Japan, South Korea and the US, to help develop skills and capabilities in new areas and improve supply chain resilience. The announcement is timely and comes as other tech ‘superpowers’ including the US, China, Japan and the EU are investing heavily in maintaining their global position in the semiconductor market.

A key takeaway is that supporting further research, innovation and commercialisation in the UK semiconductor sector is central to the government’s plan for growing the industry and the economy.

Innovation naturally leads to the generation of IP, and patents are increasingly being used as an indicator of innovation activity. The UK is currently eighth globally and third in Europe for the number of semiconductor international patent families, behind Germany and France. We expect this to change in the coming years as the success of the strategy should, in part, be reflected in a rise in the number of patent filings on semiconductor technologies.

Although perhaps not as much funding as some might have hoped for, the government’s national semiconductor strategy comes as a welcome boost to the UK’s semiconductor industry.

Mathys & Squire is proud to be ranked as a leading European patent firm by the Financial Times (FT) in their 2023 report.

The annual list is based on recommendations by clients and peers, as compiled by the FT’s research partner Statista. As well as being featured as a leading patent firm, Mathys & Squire has also been recognised in five specialist areas of industrial expertise this year: ‘Biotechnology, Food & Healthcare‘, ‘Chemistry & Pharmaceuticals‘, ‘Electrical Engineering & Physics’, ‘IT & Software‘, and ‘Mechanical Engineering.’

We would like to thank all our clients and contacts who have taken the time to recommended the firm as part of the FT’s research.

To access the full report and rankings tables, please visit the FT website here.

Bioinformatics is a rapidly growing field that combines biology, computer science, and statistics to analyse biological data. The field has become increasingly important in recent years due to the explosion of data generated by advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies.

The field has played a crucial role in advancing our understanding of genetics, genomics, and personalised medicine. However, there is a common misconception that many of the key aspects of these inventions are unpatentable such as features of genomic pipelines e.g clustering or aligning. There are of course, challenges to patenting bioinformatics methods but it can and is being done at an increasing rate.

Rise of bioinformatic-related patents

Patenting in the field of bioinformatics is not new. In fact, the first bioinformatics-related patent was filed in 1988. However, it was not until the early 2000s that the number of bioinformatics-related patents began to increase significantly. This initial increase was driven by the rapid advances in DNA sequencing technologies, which enabled researchers to generate vast amounts of genetic data. These advances led to the development of new bioinformatics tools and methods for analysing and interpreting this data.

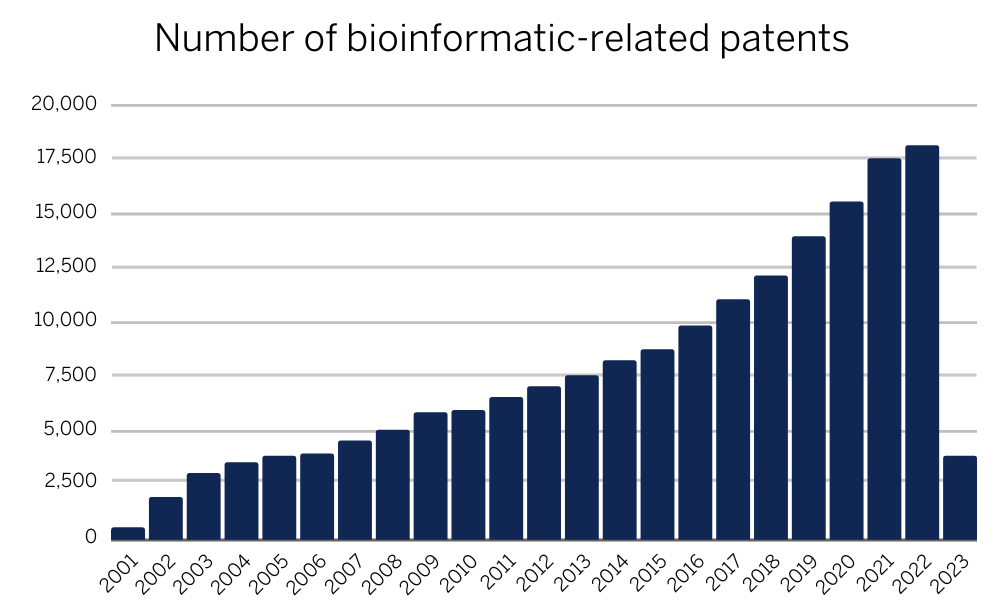

Figure 1: Increasing global trend of bioinformatics-related patents (data acquired from IP Quants)

In recent years, the number of bioinformatics-related patents has continued to increase. According to a report by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the number of bioinformatics-related patent applications increased by an average of 13.2% per year between 2013 and 2018 (Intellectual property protection indicators 2019). From data available since 2001, there has been a year-on-year increase in bioinformatics-related patents with a record-breaking number of patents filed in 2022 at just over 18,000 which is set to be broken again in 2023.

The increase in bioinformatics-related patents can be attributed to several factors.

- First, the growth of the biotechnology industry has led to increased investment in research and development. This has resulted in the development of new bioinformatics tools and methods for analysing biological data, which are often patented to protect intellectual property rights.

- Second, the availability of large datasets, such as those generated by the Human Genome Project, has made it possible to identify new targets for drug development and personalised medicine. These targets can be patented to protect the commercial rights of the companies that develop them.

- Finally, the increase in bioinformatics-related patents can also be attributed to advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning. These technologies are being used to analyse biological data and develop new algorithms for predicting disease risk, drug efficacy, and other important factors.

Growth in the bioinformatics market

The bioinformatics market is also a rapidly growing industry commercially, with a wide range of players offering products and services in the field. The global bioinformatics market in terms of revenue was estimated to be worth $10.1 billion in 2022 and is poised to reach $18.7 billion by 2027. Some of the major players in the bioinformatics market include:

- Illumina: Illumina is a leading provider of DNA sequencing and genotyping technologies. The company’s products are used in a variety of applications, including cancer research, infectious disease monitoring, and personalised medicine.

- Thermo Fisher Scientific: Thermo Fisher Scientific is a global provider of scientific and laboratory equipment, reagents, and services. The company offers a range of bioinformatics products, including software for genomic analysis, data management, and interpretation.

- Qiagen: Qiagen is a provider of sample and assay technologies for molecular diagnostics, applied testing, and academic research. The company offers a range of bioinformatics products, including software for genomic data analysis, interpretation, and visualisation.

To give an example, according to data acquired form IP Quants, Illumina Inc has over 470 patents relating to the bioinformatics field ranging from neural network-based pipeline to deep learning-based approaches, highlighting the diversity of technology available to patent within this field. These are just a few examples of the major players in the bioinformatics market. However, it is not only in industry where we have observed a rise in bioinformatics-related patents. There is a similar trend in academia. For example, the University of California has filed over 2000 patent application between 2002 and 2023, highlighting the academic interest in this field.

As the field continues to grow and evolve, new players are likely to emerge, offering innovative products and services to meet the growing demand for bioinformatics solutions.

Conclusions

The increase in bioinformatics-related patents reflects the growing importance of this field in advancing our understanding of genetics, genomics, and personalised medicine. As the field continues to evolve and expand, we can expect to see even more exciting developments and innovations in the future. It is important for researchers, industry professionals, and patent professionals to stay informed and engaged in this rapidly changing field.

A recent case at the European Patent Office (EPO) Boards of Appeal, T 1806/18, held a known drug dispersed in apple sauce and orally administered to treat its authorised condition could be inventive – despite such a formulation having been disclosed as being administered to healthy individuals in clinical trial documents.

Request

The Appellant-Proprietor appealed the decision of the Opposition Division (OD) to revoke the patent. Claim 1 of the main request read (in simplified form):

“A pyrimidylaminobenzamide of formula (I) … [the compound known as nilotinib] or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, for use in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), wherein the compound … is orally administered dispersed in apple sauce.”

Novelty

A key cited prior art document was a document from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) relating to a paediatric investigation plan (PIP) for nilotinib (document D1). D1 included three clinical study protocols: a first study in which the bioavailabilities of nilotinib capsules and dispersions in apple sauce or yoghurt were to be assessed in healthy adult volunteers, and second and third studies in which paediatric CML patients were to be administered nilotinib formulations (with no explicit mention of a dispersion in apple sauce). Whilst nilotinib was known to be effective at treating CML in adults, outcomes for none of the three trials were known by the priority date of the patent. Even though the studies were to include very young children who would not be able to swallow the capsule formulation, the Board held that “this fact does not allow concluding with certainty that this patient subset will receive the nilotinib/apple sauce formulation” (section 6.10 of the reasons), agreeing with the OD’s finding of novelty.

Inventive step

Of interest, the Board agreed with the Respondents-Opponents’ argument that the first study described in D1 was a suitable starting point for the assessment of inventive step, i.e., that this could be considered as a closest prior art disclosure despite the lack of results.

However, the Board disagreed with the Respondents’ argument that safety issues should not be considered when formulating the objective technical problem (OTP) to be solved because the reported safety issues were related to the specific use of apple sauce and not the distinguishing feature, i.e., the therapy. Instead, the Board approved of the Appellant’s reference to decision T 2506/12, which held that for a treatment to be effective, it must meet the criterion of efficacy and acceptable safety.

The Board then disagreed with the Respondents that the formulation was obvious based on D1 in light of the common general knowledge (CGK). The Board pointed to D6, that provided evidence that formulation with different foods altering the bioavailability of drugs in unpredictable ways was CGK. The Board also pointed to D58, which compared formulations of a different drug product in or with different foods, including in apple sauce, and showed there was differing drug bioavailability depending on the specific food type. D58 reports that the authors were surprised when small amounts of apple sauce caused significant delays in gastric emptying. The Board took this as further evidence of unpredictability and concluded the skilled person would not have been able to predict whether apple sauce would have any effect, and if so, how much, on the oral bioavailability of nilotinib. The Board also held that the skilled person would have been aware of other documents (e.g., D21) teaching that nilotinib can have potentially life-threatening adverse events when taken with food.

In reaching this conclusion, the Board made an interesting comment about the attitude of the skilled person when starting from D1. In particular, the Board agreed with the Respondents that “the skilled person would not have adopted a try-and-see attitude in solving the posed technical problem”, but went on to state that “this does not make the unpredictability of the food effect irrational. The fact that a clinical study is announced in a prior art disclosure does not automatically mean that its outcome was predictable and that a reasonable expectation of success had to be acknowledged.” (section 7.21 of the reasons).

The Board also dismissed the Respondents’ argument that the fact that the PIP applicant in D1 was the originator of the nilotinib capsule formulation would indicate that the applicant had a reasonable expectation of success with the claimed formulation (and that this could be inferred by the skilled person). Whilst the Board did not doubt the credibility of the content of D1, it stressed that “the respondents did not explain why the clinicians of the PIP applicant – despite being aware of the known unpredictability of the food effect of apple sauce on nilotinib – would still have had a reasonable expectation that the nilotinib/apple sauce formulation would exhibit an oral nilotinib bioavailability in healthy human adults comparable to that of the [commercial] capsule formulation” (section 7.52 of the reasons). The Board drew a distinction on the facts over decision T 239/16, which had been cited by the Respondents, on the basis that (i) the closest prior art in that case was a phase 2 clinical study; and (ii) there was no knowledge in the state of the art to diminish an expectation of success in the proposed treatment. By contrast, in the case at issue the closest prior art was a pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers, the result of which was unpredictable.

As there was no reasonable expectation of success based on D1 (or other documents) that the apple sauce formulation would have a comparable bioavailability to the capsule formulation, and hence be effective in treating CML, claim 1 was held inventive, overturning the OD’s decision.

Take home messages

This case further builds on established case law that the disclosure of planned clinical trials or clinical trials without published results do not mean the outcome of such trials is predictable, or that a reasonable expectation for success has to be acknowledged (see, for example, T 239/16). In this respect, it provides some comfort for patentees and innovators, although the Board does stress repeatedly that the correct approach will depend strongly on the facts of the case.

This particular case goes to show that even when a regulatory authority has approved a planned clinical trial in the intended patient group, a claim to the proposed treatment can still involve an inventive step. The case further illustrates how unpredictable effects of drug formulations can form the basis of a valid medical indication claim at the EPO.

Managing IP has released its 2023 guide of the IP STARS legal directory, which recognises the most outstanding practitioners covering several IP practice areas and more than 50 jurisdictions. Each year, the research analysts obtain information through firm submissions, client interviews, as well as online surveys, to identify the leading IP STARS.

We are delighted to announce that Partners Jane Clark, Hazel Ford and Paul Cozens have been named as ‘Patent Stars’ and Partners Gary Johnston and Margaret Arnott, as well as Of Counsel Rebecca Tew have been recognised as ‘Trade Mark Stars.’ Additionally, Partners Philippa Griffin, David Hobson and Andrew White have been featured as ‘Notable Practitioners’ in the latest guide. The 2023 Rising Star rankings are due to be released in September 2023.

The firm is also pleased to have maintained its rankings for ‘Patent prosecution’ and ‘Trade mark prosecution’ in the 2023 directory.

For more information, and to view the rankings in full, visit the IP STARS website here.

Pride Month is a time to celebrate the accomplishments, resilience, and contributions of the LGBTQIA+ community. While progress has been made towards equality and acceptance, it is important to recognise the trailblazing innovators who have left an indelible mark on the world.

From groundbreaking scientific discoveries to transformative technological advancements, LGBTQIA+ individuals have played a crucial role in shaping our society. In this article, we at Mathys & Squire celebrate the achievements of some remarkable innovators and inventors who have inspired change and left an important legacy.

Alan Turing unleashed the power of computing

Alan Turing, a gay mathematician, logician, and computer scientist, is widely regarded as the father of modern computer science. His work during World War II in cracking the German enigma code was instrumental in the allied victory. Alan’s conceptualisation of the Turing machine laid the groundwork for modern computing and artificial intelligence. Despite his brilliance, Turing faced persecution due to his sexuality, reminding us of the profound impact discrimination can have on human potential.

Lynn Conway pioneered microelectronics

Lynn Conway, a transgender woman, is an esteemed computer scientist and electrical engineer known for her invaluable work in the field of microelectronics. Her innovative research on the very large scale integration chip design revolutionised computer architecture. Conway’s work has been instrumental in enabling the development of modern computers, smartphones, and other electronic devices. She is an advocate for transgender rights and has been an inspiration to countless aspiring engineers.

Martine Rothblatt pushed the boundaries in biotechnology

Martine Rothblatt, a transgender entrepreneur, lawyer, and author, has made significant contributions to the fields of biotechnology and healthcare. As the founder of United Therapeutics, Rothblatt focused on developing treatments for pulmonary hypertension. She also spearheaded advancements in xenotransplantation, the transplantation of organs between species, with a focus on utilising pig organs to address the organ shortage crisis. Rothblatt’s work exemplifies the potential for innovation when diverse perspectives are embraced.

Benjamin Barres revolutionised neuroscience

Dr. Benjamin Barres was a transgender neurobiologist, whose innovative work contributed to our understanding of the brain and its functions. His research focused on glial cells, which were once considered passive support cells but are now known to play a critical role in brain development and function. Barres’s work challenged prevailing dogmas and opened new avenues of exploration in neuroscience. He was an outspoken advocate for gender equality in academia and worked to address the underrepresentation of women and transgender individuals in science.

Chien-Shiung Wu transformed nuclear physics

Dr. Chien-Shiung Wu, a lesbian physicist, made groundbreaking contributions in the field of nuclear physics. Known as the ‘first lady of physics’, Wu played a pivotal role in disproving the law of conservation of parity, which had been considered a fundamental law of physics. Her experiments, including one known as the Wu experiment, provided evidence for the violation of parity symmetry in weak interactions. Wu’s work fundamentally reshaped our understanding of the fundamental forces of nature. Despite facing gender and racial discrimination during her career, she persevered and left an indelible mark on the field of physics.

Sarah McBride fighting for LGBTQIA+ rights

While not an inventor in the traditional sense, Sarah McBride, a transgender activist, is an innovator in the realm of LGBTQIA+ rights and political advocacy. As the first openly transgender person to speak at a major party convention in the United States, McBride has been a prominent voice for equality and inclusion. Her work focuses on advancing legislation to protect LGBTQIA+ individuals from discrimination, and she continues to inspire others with her advocacy and commitment to social justice.

Tim Cook revolutionising the technology landscape

Tim Cook is a prominent figure in the technology industry and the CEO of Apple Inc. He succeeded Steve Jobs and has been instrumental in shaping the company’s success. Cook, who is openly gay, has been a vocal advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights and workplace inclusion. Under Cook’s leadership, Apple has continued to innovate and introduce groundbreaking products, revolutionising the technology landscape. Cook’s emphasis on user-friendly design, sustainability, and privacy has garnered praise and contributed to Apple’s continued growth and influence. His strategic vision and commitment to excellence have solidified Apple’s position as one of the world’s leading technology companies.

As we celebrate Pride Month, it is essential to recognise the invaluable work of LGBTQIA+ innovators and inventors who have reshaped the world with their brilliance and courage. From Alan Turing’s pioneering work in computing to Lynn Conway’s transformative research in microelectronics, these individuals have left a legacy that extends far beyond their respective fields. Their achievements serve as a testament to the power of diversity, inclusivity, and the limitless potential of human ingenuity. Mathys & Squire continues to honour and support LGBTQIA+ innovators as we strive for a future where everyone can thrive and contribute their unique talents to building a better world.

Today, 1 June 2023, marks the launch of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) and the Unitary Patent (UP) system after many years of preparation by the European Union and its members. As of today, the UPC has jurisdiction for patent litigation throughout the 17 member states which have ratified the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court (UPCA). From today onward, newly-granted European patents can also be brought into force as Unitary Patents, providing coverage for the 17 UPC member states through a single validation.

Any existing European Patents that have not been opted out are now automatically subject to the UPC’s jurisdiction. However, you can still choose to opt your patents out throughout the initial transitional period of at least seven years, provided that those patents are not subject to litigation at the UPC. Once opted out, patents will be subject to the jurisdiction of the competent national courts instead. Opt-outs can also be registered for pending European patent applications.

During the three-month sunrise period which ended yesterday, a total of nearly 474,000 patents and patent applications were opted out. Although precise figures are hard to calculate, it has been estimated that this represents somewhere between about 40 and 60% of all eligible patents and patent applications, with the number expected to continue to rise now that the court is open for business. It will be very interesting in the coming weeks and months to see how widely the UPC is adopted as a forum for patent litigation instead of national courts, and to see if any sectoral trends begin to emerge.

In other news which was announced at a late stage of the sunrise period, it has been confirmed that (subject to a confirmatory vote by the UPC’s Administrative Committee) Milan will host the third branch of the UPC’s Central Division, which was relocated from London due to Brexit. However, no formal announcement has yet been made as to which cases will be handled in Milan, and it seems that the Milan branch will not be opening just yet. For the time being, therefore, cases at the UPC’s Central Division will be split between Paris and Munich as we reported previously.

With our patent attorneys eligible to practice before the UPC as registered European Patent Litigators, our team at Mathys & Squire is well equipped to assist you in carving out your individual filing and litigation strategy. As we step into the unknown, we are thrilled to watch the new system change patent litigation forever, and to be part of shaping its course.

Read more about UPs, the UPC and opting out of the UPC here.