Following the Decision of the Administrative Council of 14 December 2023, the European Patent Office (EPO) has announced a general increase in official fees, a year after its last fee increase in 2023. A complete breakdown of the increases is available on the EPO website.

Whilst some fees have been left unchanged, others have undergone modest changes of only about 4%. Most notably the renewal fees for the 3rd to 5th year have jumped significantly, ranging from 8 to 30% increases. Interestingly, the 6th year renewal has actually been reduced (2%).

For more information about the fee increases and how they may affect you, as well as to discuss any potential cost savings, please get in touch with your usual Mathys & Squire attorney, or send us an enquiry.

Commentary by Partner Alan MacDougall has been featured in The Patent Lawyer, highlighting differences between the UK and US patent filing process and the importance of protecting research and development investment for banks whenever possible.

An extended version of the press release is available below.

The UK’s biggest banks have filed just a fraction of the patent applications of their American counterparts over the last 10 years, with the top five UK banks collectively applying for just 290 patents while the top 3 US banks collectively applied for 5,027, says intellectual property law firm Mathys & Squire.

The low number of patent applications filed by UK banks is partly due to the lengthy and complex filing process in the UK but also due to a misplaced notion that software is not patentable in the UK. This has resulted in more frequent and more successful filings in the US.

The US patent application process has slowed down significantly over recent years as the number of applications has increased. Even with much longer wait times, it remains markedly easier to obtain protection for a financial services related patent in the US than in the UK.

Whilst obtaining patent protection for software related inventions is possible in the UK, the UK IPO has long been reluctant to grant patents for software that relates to financial products. The strict rules it applies to whether a piece of software is patentable means that relatively few fintech software patents are actually granted in the UK, discouraging the banks from trying in the first place.

Alan MacDougall, Partner at Mathys & Squire, says that it is essential that banks protect their research and development (R&D) investment as much as possible by patenting their technology where they can. In a competitive marketplace, unique technology can set financial services businesses apart from their rivals and help to win and retain customers.

Patent-protected technology can also serve as a significant source of income in itself, as the owners of the technology can then license it to other businesses and can be used as a bargaining tool in the event that they find that their products infringe the rights of others.

While it’s common to see tech companies secure IP with patents, financial services companies frequently do not take the same approach. Alan MacDougall says that “Banks are amongst the biggest investors in tech development in the UK but they are still not being as vigilant as they should be about protecting the intellectual property that their funding helps to generate.”

“We’d never expect a tech company to release a new product without trying to patent it first. Financial services institutions should be thinking about their IP in the same way. They should be trying to protect their IP with patents. Leaving that valuable IP open to being copied reduces the return on the investment from the R&D that the banks are undertaking.”

By default, European patents granted by the European Patent Office (EPO) in effect in countries participating in the Unified Patent Court (UPC) are subject to the jurisdiction of that Court. However, patent proprietors have the option to opt their European patents out from the UPC’s jurisdiction. Such opt-outs are defensive in nature as an opt-out protects a European patent from being revoked in a single court action. Opted-out patents can only be revoked in national proceedings brought on a country-by-country basis.

Given the defensive nature of UPC opt-outs, it would be expected that one factor which patent proprietors will consider when deciding whether to opt patents out of the jurisdiction of the UPC would be the likelihood of revocation actions being brought against their patents. EPO oppositions are by far the most common form of revocation action which are brought in Europe. Hence, EPO opposition rates should provide a reasonable indication of the rate at which revocation actions are sought against patents in different technologies. With that in mind, it would be expected that in general there might be a correlation between EPO opposition rates and opt-out rates in different technologies. But is that really the case?

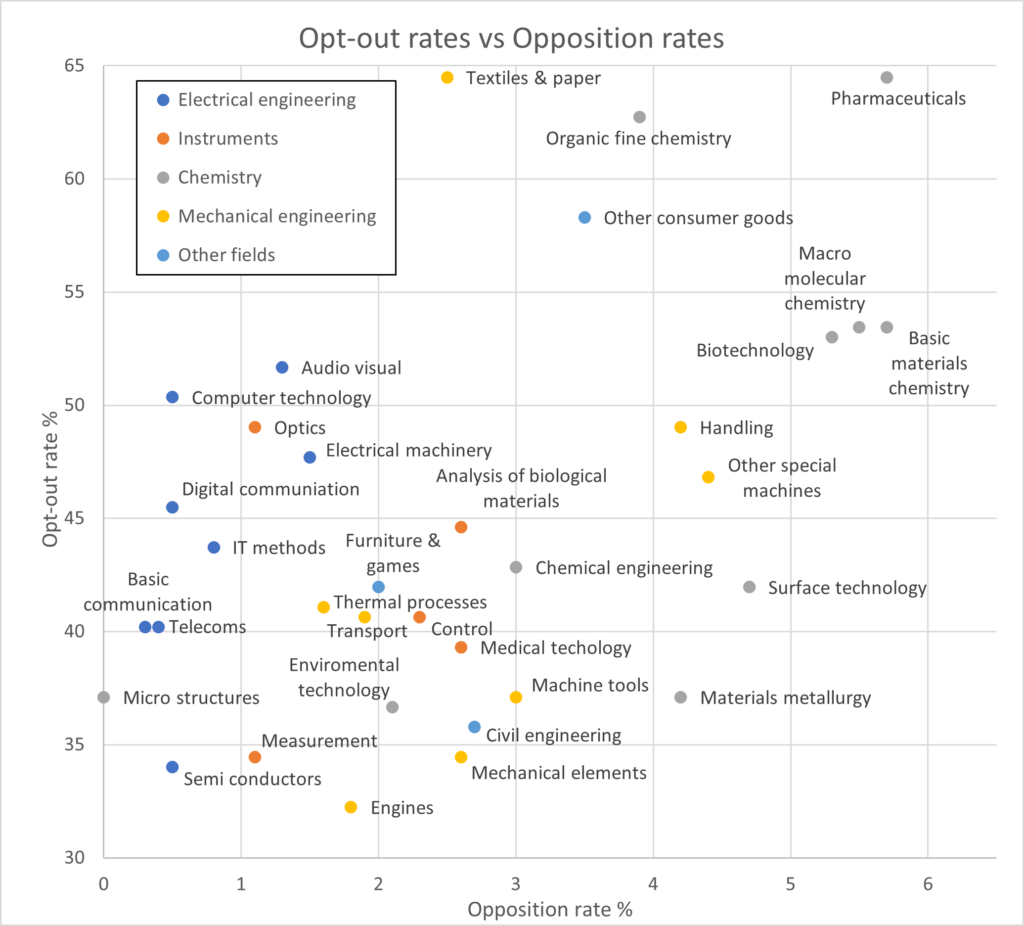

Differences in opt-out rate vs EPO opposition rate across technical fields

The figure below shows the opt-out rate vs. EPO opposition rate for the different technology fields for which the EPO grants patents apart from food chemistry which has been omitted in the interests of clarity due to the exceptionally high rates of opposition filed against Food Chemistry patents.

As can be seen in the graph above, there is relatively little correlation between opt-out rates and opposition rates across technologies as a whole. However, a glance at the graph does demonstrate that there are very few technologies associated with high-opt out rates which are associated with low opposition rates and vice versa.

Part of the problem with considering opt-out and opposition rates across all technologies is that opposition rates vary considerably across technical fields. For that reason, it is worthwhile drilling down and considering patents in related technical fields.

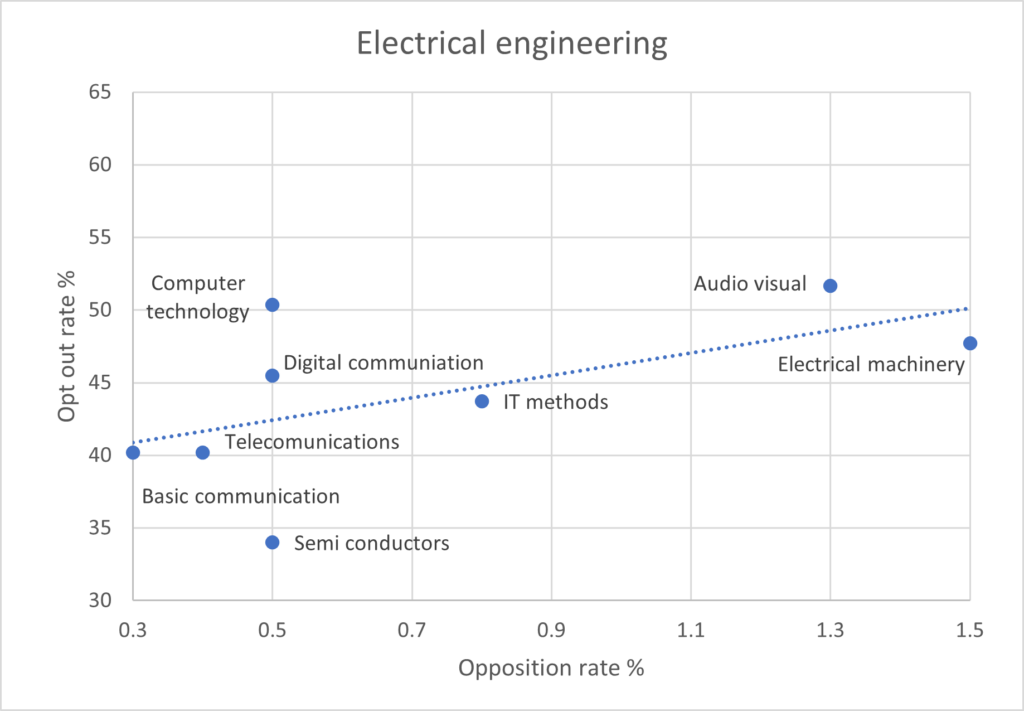

Assessing opt-out rates and opposition rates in electrical engineering fields

The following graph illustrates opt-out rates and opposition rates, but this time only considering technologies in electrical engineering.

When only electrical engineering patents are considered, then a much stronger trend appears with a significant proportion of variation of opt-outs across different fields being correlated with EPO opposition rates. As a whole, across electrical engineering technologies, differences in opposition rate account for around a third of the variation of opt-out rates. As can be seen from the graph above, most of the remaining variation is accounted for by the relatively high opt-out rate of computer technology patents compared with the numbers of oppositions filed against such patents and the relatively low opt-out rate of semi-conductor patents.

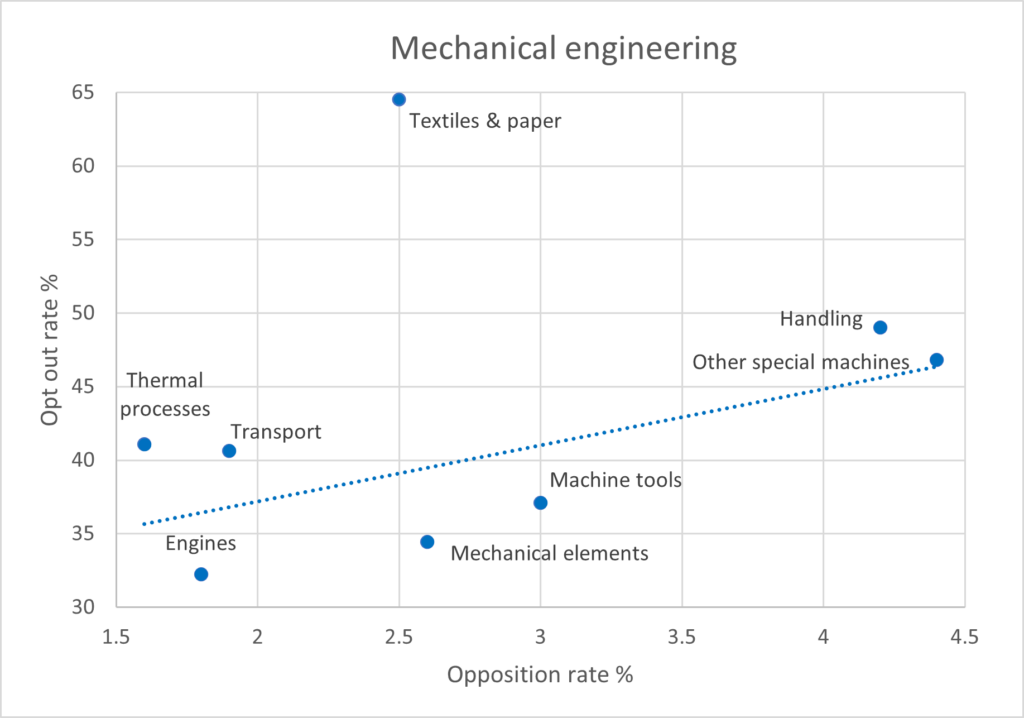

Comparable patterns in patents related to mechanical engineering

Similar trends can also be observed with mechanical engineering patents, with one obvious clear exception, namely patents in the field of textiles and paper, which have opt-out rates far in excess of what might be expected given the relatively low numbers of oppositions which are filed against such patents. In the graph below, the trendline for mechanical engineering patents other than in the field of textiles and paper is shown. If textiles and paper inventions are excluded, the variation in opposition rates accounts for around half of the variation in opt-out rates across mechanical engineering technologies.

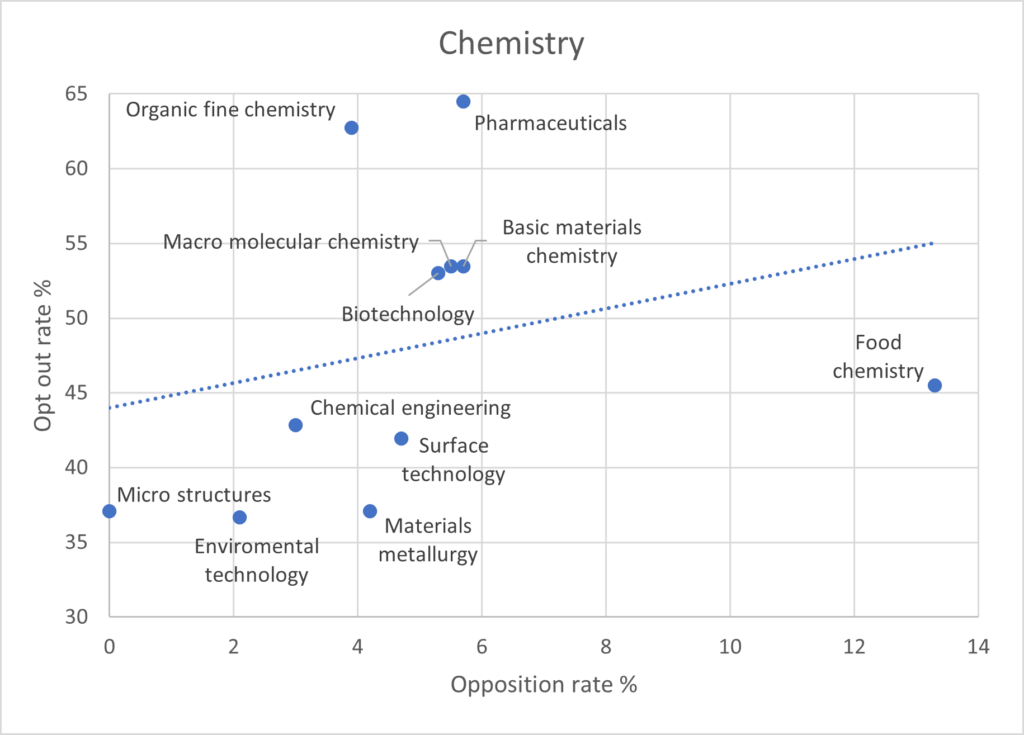

More variation in chemical technology fields

Significantly more variation is to be found in chemical technologies, illustrated in the graph below. Food chemistry has been included in this graph as the higher rates of opposition in chemical technologies as a whole mean that the inclusion of food chemistry with its very high rates of opposition does not cause the opposition rates for other technologies to cluster as would have done in the first figure.

As can be seen in this graph, there is practically no correlation between opt-out rates and opposition rates across chemical technologies, with variation in opposition rates explaining only around 7.5% of the variation in opt-out rates in chemical fields. This suggests that factors, other than the actual likelihood of revocation actions being brought, are the primary factors behind the variation in opt-out rates in different fields of chemistry. Most likely, the significant value of some chemical patents, particularly those in the pharmaceutical field, results in extra caution on the part of patent proprietors in certain fields where the risk of a revocation action is not insignificant, and the potential commercial impact of the loss of individual patents can be very large.

Conclusions

Proprietors’ assessment of the risk of revocation is clearly only one of many factors which proprietors consider when deciding whether to opt their patents out of the jurisdiction of the UPC. The costs involved in filing and registering UPC opt-outs are limited and as a result significant numbers of European patents have been opted-out. If the risk of central revocation is a significant one, it would be expected that patent proprietors are well placed to identify patents which are at risk. However, other factors are clearly of importance and the extent to which out-opts have been risk-based has varied considerably across different technological fields.

Commentary by Partners Nicholas Fox and Alexander Robinson has been featured in Kluwer Patent Blog, Law 360, Managing IP, Solicitors Journal and World Intellectual Property Review, giving an insight into the impact of the Court of Appeal’s order on future interventions in proceedings at the UPC.

An extended version of the press release is available below.

The Unified Patent Court (UPC) Court of Appeal has dismissed an attempt by Mathys & Squire to intervene in a critical test case on public access to documents filed with the Court. An attempted intervention by the law firm Bristows was also dismissed.

Background

In October the UPC’s Nordic-Baltic regional division granted a request by a member of the public to access documents filed at the court in a patent infringement action between Ocado and Autostore. However, access was stayed after Ocado asked the UPC Court of Appeal to overturn that decision, which conflicts with a narrower view taken by the UPC’s Central Division requiring members of the public to prove a “legitimate reason” in order to access such documents.

In November, Mathys & Squire applied to intervene in the Appeal on the basis that Court of Appeal’s decision was likely to be determinative of a separate application for access to documents that Mathys & Squire has filed before the UPC’s Central Division. Bristows likewise applied to intervene in December in view of a pending request that the firm had filed for access to documents at the UPC’s local division in the Hague.

The Court of Appeal’s order

In its ruling (see here), the Court of Appeal interpreted the grounds on which third parties can intervene in an appeal very narrowly, limiting applications to cases where a third party has a direct interest in the wording of an order which the Court might issue.

Specifically, the Court held that an intervention requires a “direct and present interest in the grant by the Court of the order or decision as sought by the party, whom the prospective intervener wishes to support and not an interest in relation to the pleas in law put forward.”

Our application to intervene, and that of Bristows, were both rejected on the grounds that an interest in a decision based on an “indirect interest” such as “similarity between two cases” (e.g. similarity between our request for access to documents at the Central Division and the request for access to documents at the Nordic-Baltic division) was insufficient.

The Court of Appeal’s order sets an important precedent. It means that interventions in proceedings at the UPC will only be allowed in narrowly-defined circumstances. In adopting this narrow interpretation, the UPC Court of Appeal has adhered closely to the practice of the CJEU, where possibilities for interventions by third parties are very limited.

Where next for our application at the Central Division?

The Munich Section of the Central Division has stayed Mathys & Squire’s application to access for documents pending the outcome of the Ocado and Autostore Appeal. We therefore have to wait for the outcome of the Ocado and Autostore Appeal until our application for access to court documents will proceed further.

If the Court of Appeal delivers a decision which provides wide-ranging guidance on the interpretation of the UPC rules on public access to documents, with reasoning which is applicable to most circumstances, this may resolve our concerns about the Court’s current restrictive approach to public access to pleadings and evidence filed with the Court.

It is, however, possible that these issues will not be resolved in the Ocado and Autostore appeal. The circumstances of the access request in the Ocado and Autostore appeal raise specific questions which may cause the Court of Appeal to issue a narrow ruling. We understand that one of the objections that Ocado have raised is that some of the requested pleadings were never properly served and hence do not form part of the court file.

Mathys & Squire have been in contact with the member of the public whose original request for access is the subject of this Appeal. We have provided him with copies of our materials to support his arguments in defence of the public interest in judicial transparency, and wish him the best of luck.

Continuing reservations over speed and transparency at the UPC

Our concerns about the transparency of court proceedings at the UPC persist.

The original request for access to the Ocado and Autostore documents was filed by a member of the public in August last year. Although the Court of Appeal was to hold oral proceedings in mid-February, the hearing has now been rescheduled for mid-March and hence any decision by the Court of Appeal is unlikely to issue much before April. This means that it will have taken over 6 months for the UPC to process what should be a simple administrative request for access to court documents.

According to the UPC’s case management system, 13 applications for access to court documents have been filed since the UPC opened in June. Two of those requests have been rejected, leaving 11 still pending. To date, none of the applications have resulted in members of the public having sight of evidence and pleadings filed with the court.

We will await the outcome of the Ocado and Autostore with interest.

Mathys & Squire is delighted to have been recognised in JUVE Patent’s UK rankings 2024 for the fifth consecutive year in the fields of ‘Pharma and biotechnology’, ‘Medical technology’, ‘Chemistry’, ‘Digital communication and computer technology’, ‘Electronics’ and ‘Mechanics, process and mechanical engineering’.

As well as a practice-wide recommendation for the firm, four of our Partners have maintained their status as Recommended Individuals: Hazel Ford and Philippa Griffin (for ‘Pharma and Biotechnology‘), Chris Hamer (for ‘Chemistry‘) and Jane Clark (for ‘Digital Communication and Computer Technology‘ / ‘Mechanics, Process and Mechanical Engineering‘).

Partner Chris Hamer has also maintained his specialist Leading Individual ranking once again this year for his expertise in chemistry, one of only eleven UK patent attorneys noted for their technical speciality.

Each year, JUVE Patent rankings are carefully researched by an independent team of journalists, who send out questionnaires and conduct interviews with lawyers, clients, legal academics and judges. The 2024 edition brings together UK patent practices, solicitors and barristers, who, according to the in-depth research carried out by a team of journalists, have a leading reputation in the UK patent law market.

To see the JUVE Patent UK 2024 rankings in full, please click here.

The Supreme Court has today confirmed that artificial intelligence (AI) systems cannot currently be named as an inventor on a patent application in the UK. It has also confirmed that an owner of an AI system that creates a new invention is not entitled to a patent for that invention simply by virtue of owning the AI system.

Background

This case concerns two UK patent applications filed in 2018 for inventions allegedly created by an AI system called “DABUS” (Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience). The patent applications were filed by Dr Stephen Thaler (the creator and owner of DABUS), but DABUS was named as the inventor on each application.

Sections 7(3) and 13(2) of the Patents Act 1977 define the inventor of a UK patent application as the “actual deviser” of an invention and that the applicant must identify the “person” they believe to be the inventor. Section 7(2) also states that a patent may be granted primarily to the inventor or to any person entitled by agreement or rule of law, or their successor in title.

Applicants for patents at the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) are therefore required to file a statement of inventorship and, if the applicant is not the inventor, to indicate how they derived the right to be granted a patent.

In the case of Dr Thaler’s applications, he not only indicated that DABUS was the inventor but also maintained that he himself was not an inventor. He asserted that he was entitled to grant of the patents by virtue of owning DABUS.

At a hearing in November 2019, Dr Thaler’s arguments were rejected by the UK Intellectual Property Office on two grounds:

(a) DABUS is non-human so is not a “person” as envisaged by section 7 or section 13 of the Patents Act, and therefore cannot be an inventor, and

(b) Dr Thaler is not entitled to apply for these patents simply by virtue of owning DABUS, since DABUS – not being a “person” – had neither any rights that could be transferred, nor any power to transfer anything that it might have owned.

Accordingly, the applications were held to be withdrawn upon expiry of the period for providing the statement of inventorship.

Dr Thaler appealed this refusal, but his appeal was dismissed in the High Court and subsequently the Court of Appeal in September 2021 (on a 2:1 majority). This was then appealed further to the Supreme Court, who have now also dismissed the appeal.

The Judgment

The Supreme Court considered this appeal to be concerned with the relatively narrow question of how the relevant provisions of the Patents Act 1977 should be interpreted, rather than a broader policy consideration of whether the meaning of the term “inventor” should be expanded to allow AI systems to be named as inventors.

On the first issue of whether DABUS could be named as an inventor, the Supreme Court unanimously found that an inventor must be a natural person. Lord Kitchin noted that, at the time of drawing up the Patents Act, Parliament did not contemplate the possibility that an AI system acting on its own could devise an invention, so the laws are not intended to cover this possibility.

The second issue, namely whether Dr Thaler was entitled to the grant of a patent for the inventions created by DABUS, has also been answered with a “no”. Lord Kitchin explained that since DABUS cannot be and has never been an inventor, and that Dr Thaler has himself admitted that he is not an inventor, there is no link between Dr Thaler and an inventor (i.e. no link of the type provided for in the Patents Act, such as an employer-employee relationship or other succession in title). As the Patents Act provides a “complete code” for the purpose of determining the right to apply for and obtain a patent, which starts with the inventor, then the absence of an inventor must cause the application to fail.

Although Dr Thaler argued that as the owner of DABUS he was entitled to the grant of patents for inventions created by it under the doctrine of accession (in the same way that a farmer owns a calf born to his cow), this argument was also dismissed. The Court held that on the basis that an invention is not tangible property, there is no basis for the application of the principle of accession.

Finally, the third issue considered was whether the UKIPO was correct to treat Dr Thaler’s applications as withdrawn. The Supreme Court agreed with the findings of the lower courts that Dr Thaler did not meet the requirements of Section 13(2) of the Patents Act, so his applications were rightfully deemed withdrawn.

Comments

This judgment is consistent with the current laws on inventorship and entitlement, although as flagged by Lord Kitchin, this is partly due to the fact that they were drawn up some time ago before issues of AI inventorship would have been envisaged. However, with the increasingly rapid development and adoption of generative AI, these issues are unlikely to go away any time soon.

It is worth noting that the Supreme Court emphasised that neither the UKIPO nor the courts investigated Dr Thaler’s assertions of fact, namely that the inventions were generated autonomously by DABUS and that Dr Thaler was not an inventor. Indeed, it is not the function of the UKIPO to investigate the factual correctness of such statements. As recognised by the Supreme Court, the outcome may well have been different if Dr Thaler had asserted that he was an inventor who had merely used DABUS “as a highly sophisticated tool”.

Although corresponding cases in Australia and South Africa found that an AI machine could be named as an inventor, for the time being applicants in the UK will therefore need to identify the human inventors who have devised the invention. In the context of AI-generated or AI-assisted inventions, this still leaves several grey areas in determining who should be named as an inventor – for example, whether it should be the creator, owner or user of the AI system, or even someone who has identified the inventive concept of an invention created by an AI system.

We look forward to seeing how patent law in the UK and overseas continues to respond to challenges posed by AI.

Following an extended 14-day conference in the UAE, the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference(COP28) concluded on the 13th of December 2023. As ever, the annual climate conference beings together delegates from across the world to set the course for the future of the green economy.

Following COP21 and the almost unanimous decision to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5°C, these conferences typically focus on ways and means to meet this target, for instance by limiting the emission of carbon dioxide (one of the largest contributors to climate warming).

A move away from fossil fuels

One major outcome of COP28 was the agreement to transition away from fossil fuels in the energy sector ‘in a just, orderly and equitable manner’. This is to be achieved by a rapid expansion in renewable energy production and exploring emerging technologies such as carbon capture, usage, and storage (CCUS). Being hailed as the most important agreement for the climate since COP21, technologies that address this issue are likely to become a key sector of growth over the coming years.

Whilst the agreement was limited to the energy sector, away from COP28 we have seen numerous developments this year in the decarbonisation of those sectors which are more reliant on fossil fuels; namely the aviation and automotive sectors. The first transatlantic flight by a sustainably fuelled jet airliner took place just two days before the opening day of COP28, potentially paving the way for reducing the emissions of the most difficult sector to decarbonise. Furthermore sustainable fuels continue to see potential in the automotive sector, including in motorsport.

Green Climate Fund

The Green Climate Fund (GCF) was founded at COP17 on the basis of richer countries (historically responsible for the most carbon emissions) providing funding to mitigate the effects of climate change in poorer countries (often disproportionally affected by climate change). COP28 saw the GCF rise to $12.8Bn pledged from 31 countries and forms part of a larger commitment set out at COP15 for developed countries to commit $100Bn per annum towards affected countries. One of the purposes of the GCF is to accelerate and scale up climate innovation, including by encouraging more widespread adoption of proven climate solutions by enhancing financing of climate investments. With the continued growth of the GCF, we might expect more investment to become available for innovators in this area.

Whilst not without its controversies, COP28 stands to reaffirm the importance of cleantech and the potential opportunities for innovation, particularly in the energy sector and in technologies relating to the replacement of fossil fuels in other sectors.

At Mathys & Squire, we work with many cleantech clients on green technology breakthroughs and sustainable solutions. We are pleased to partner with companies and inventors who are addressing climate change and whose initiatives further the objectives set forth by COP28.

The outcome of the test case filed by Mathys & Squire to secure public access to evidence in the Unified Patent Court (UPC) is expected early in 2024. Commentary provided by Mathys & Squire has been featured in JUVE Patent, Law 360, the Solicitors Journal and World Intellectual Property Review.

An extended version of the press release is available below.

The Unified Patent Court (UPC) has now set a schedule for hearing an appeal which is likely to be determinative on the rights of the public to access evidence and pleadings filed with the Court.

Two weeks ago, Mathys & Squire brought a test case before the Munich Section of the Central Division of the UPC arguing that, by default, evidence and pleadings filed with the Court should normally be made available to third parties on request and that access should only be restricted when it is absolutely necessary to protect confidential or personal information.[1]

Mathys & Squire also applied to intervene in an appeal where a party is seeking to overturn the decision of a judge in the UPC’s Nordic-Baltic division to permit a third party to obtain copies of evidence and pleadings.[2]

The appeal pending before the UPC Court of Appeal has now been assigned to the second panel of the Court of Appeal with judge Ingeborg Simonsson being appointed as the judge-rapporteur for the appeal. Ms. Simonsson has been a full time judge in the Swedish courts since 2008 and in 2020 was appointed Judge in the Svea Court of Appeal and the Patent and Market Court of Appeal.[3]

Judge Simonsson has now set a 15-day deadline for the parties to comment on Mathys & Squire’s application to intervene. She will then make a decision as to whether or not to accept Mathys & Squire’s application. The parties will then be given a further 15 days to submit written arguments to the court on the substance of the appeal. An oral hearing will then be held on 15 February 2024.

Nicholas Fox, Partner at Mathys & Squire, says: “We welcome the appointment of Judge Simonsson as judge-rapporteur in the appeal. The Swedish Courts have an exceptionally long history of transparency and openness, and the principle of public access is considered an essential principle of Swedish law. Judge Simonsson will be an excellent judge to consider this appeal.”

The case pending before the Munich Section of the Central Division has been stayed pending the outcome of the Appeal.[4]

Alexander Robinson, Partner at Mathys & Squire, says: “The decision to stay the proceedings pending the Court of Appeal decision supports our arguments that we have a legal interest in the appeal and should be allowed to intervene.”

In the cases being brought, Mathys & Squire are being represented by Nicholas Fox and Alexander Robinson, partners from our London office, and Andreas Wietzke, a partner from our Munich office.

[1] Pending as case no. APP_588681/2023. A copy of the arguments that Mathys & Squire submitted to the court is available here.

[2] Case No. APL_584498/2023,

[3] A biography of Judge Simonsson can be found here.

[4] Preliminary Order UPC_CFI_75/2023

Four Mathys & Squire Partners, Anna Gregson, Dani Kramer, Sean Leach, and Martin MacLean, have been recognised in the 2024 edition of IAM Strategy 300 Global Leaders.

Since its inception, the guide has been a platform that highlights the top experts within the field of intellectual property (IP). Securing a spot in the esteemed IAM Strategy 300 Global Leaders is a testament to a professional’s strategic prowess in intellectual property, as recognised by peers across various domains.

IAM says: Anna Gregson couples a nuanced understanding of patent law with a deep knowledge of the biotechnology and life sciences industries to provide holistic and proactive strategic advice. She leaves no stone unturned in her analyses in order to deliver the best possible result for her clients.

IAM says: Highly experienced patent attorney, Dani Kramer brings a vast knowledge of the law and experience at the European Patent Office. He is the go-to practitioner for providing guidance when dealing with complicated and sensitive cases at the EPO.

IAM says: Sean Leach is a big picture thinker who effectively finds and maximises the commercial value for clients in the hard technology sector. He pairs immense technical knowledge with an understanding of his clients’ commercial goals to deliver top-tier strategic advice.

IAM says: Martin MacLean is a dynamic and agile attorney who masterfully devises creative IP solutions. He goes above and beyond to meet and exceed client expectations and dives into the details of their business to ensure his advice aligns neatly with their commercial goals.

We would like to express our thanks to every client, contact, and peer who dedicated their time to engage in the research process.

The full 2024 edition of the guide is available here.

The UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) has published new guidance setting out that patent examiners should not object to inventions involving an artificial neural network (ANN) under the “program for a computer” exclusion of section 1(2)(c) of the Patents Act 1977.

On 21 November 2023 the UK High Court handed down its judgement in Emotional Perception AI Ltd v Comptroller-General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks [2023] EWHC 2948 (Ch). The judgement related to whether an invention involving an ANN constituted excluded subject matter as a “program for a computer … as such” under section 1(2)(c) of the Patents Act 1977.

The judgement held that the trained ANN of the claimed invention was not a computer program at all and thus did not engage the relevant exclusion. The judgement also held that, in any case, the invention involved a substantive technical contribution going beyond a program for a computer “as such”.

Following this judgement, the UKIPO temporarily suspended their guidelines for examining patent applications relating to artificial intelligence (AI) inventions (see here) and published brief new guidance (see here). Under the new guidance, patent examiners should not object to inventions involving an ANN under the “program for a computer” exclusion of section 1(2)(c) of the Patents Act 1977.

Notably, the judgement did not address whether an invention involving an ANN constitutes excluded subject matter as being a “mathematical method … as such” under section 1(2)(a) of the Patents Act 1977, which is another objection that is often raised in relation to AI and machine learning inventions.

This is a significant development which might, for the time being at least, make it easier for applicants to obtain patents for AI inventions in the UK. It remains to be seen whether the judgement will be appealed.