Mathys & Squire is delighted to announce that our trademark team has been recommended in the 2025 edition of the World Trademark Review (WTR) 1000 guide. Partners Gary Johnston, Rebecca Tew and Helen Cawley and Consultant Margaret Arnott all featured as Recommended Individuals.

The WTR 1000 directory illustrates the depth of expertise available to clients, serving as the definitive tool for those seeking outstanding trademark services worldwide. Now in its 15th year, the WTR 1000 has firmly established itself as the definitive ‘go-to’ resource for those seeking stellar trademark expertise and partners worldwide. Mathys & Squire has been recommended for its work in the trademark field, specifically in the ‘prosecution and strategy’ category. “Mathys & Squire are incredibly easy to work with. The team possess extensive knowledge in all aspects of trademark law, ensuring an exceptionally effective and efficient A-to-Z service.”

Alongside our firm ranking, Consultant Margaret (recommended in the categories of ‘Enforcement & Litigation’ and ‘Prosecution & Strategy’), Helen (recommended in the category of ‘Prosecution & Strategy’), Gary (recommended in the category of ‘Prosecution & Strategy’) and Rebecca (recommended in the category of ‘Prosecution & Strategy), have received the following testimonials:

“Helen Cawley adeptly manages a wide range of instructions. She draws on two decades of experience to provide insightful and proactive advice that helps clients align their trademark strategies with their commercial goals. Cawley’s strategic vision and dedication are poised to make a significant impact on the team and its clients.“

Gary Johnston is “an agile practitioner who seamlessly integrates legal insights with commercial acumen, crafting practical solutions that achieve outstanding results. He recently represented the John Cotton Group in successfully opposing the registration of the mark ‘SNUGGLEMORE’, utilising their established rights in the mark and affirming its reputation and goodwill.“

Rebecca Tew “excels in devising and implementing effective protection and enforcement strategies. She adeptly tailors her approach to meet the unique needs of each client, whether a start-up or a multinational corporation, consistently delivering exceptional service. “

Margaret Arnott “navigates both contentious and non-contentious waters with finesse. Always practical and sensible, she has a knack for crafting business-friendly solutions to any challenge that comes her way.”

We would like to thank each of our clients, contacts and peers who took the time to participate in the research. For more information and to see the full WTR 1000 rankings, please click here.

The UK’s deep tech sector is a rapidly evolving landscape that thrives on ground breaking scientific and engineering advancements. From quantum computing to advanced semiconductor technologies, deep tech companies are driving innovation and reshaping industries. However, while technological breakthroughs are the foundation of deep tech, intellectual property (IP) plays a crucial role in safeguarding innovations, attracting investment, and ensuring commercial viability. This evolving landscape is explored in greater detail in the Royal Academy of Engineering’s State of UK Deep Tech 2024 report.

Despite its strong foundation, the UK’s deep tech sector faces several challenges that could hinder its long-term success:

- Insufficient Public and Private R&D Investment: While government funding supports deep tech research, better alignment with private sector investment is needed to drive commercialisation.

- Lack of Investor Technical Expertise: A shortage of UK-based investors with deep technical knowledge makes it difficult for deep tech startups to secure informed and strategic backing.

- Challenges in Academic-Industry Collaboration on IP: Universities play a key role in IP generation, but rigid IP agreements can hinder spinout success, requiring more flexible frameworks.

- Limited Access to Infrastructure and Talent: A shortage of affordable lab space, advanced manufacturing facilities, and skilled professionals presents significant barriers to scaling deep tech companies.

The Deep Tech Investment Landscape

According to the Royal Academy of Engineering’s State of UK Deep Tech 2024 report, UK deep tech companies have consistently attracted substantial venture capital (VC) investment. Since 2020, the sector has annually secured over £5 billion in VC funding, with healthcare and artificial intelligence gaining the most investment. However, despite this promising trend, the UK still faces significant challenges in scaling deep tech ventures, particularly when compared to the US. One of the key reasons for this is the complex and capital-intensive nature of deep tech, which requires long-term financial backing and industry-specific expertise from investors.

The UK’s venture capital ecosystem has seen an increasing presence of nontraditional investors, including corporate venture capital (CVC) firms and sovereign wealth funds. With 32.5% of UK deep tech VC deals involving no UK investors in early 2024, it is evident that global players recognise the immense potential of the sector. Nevertheless, a gap remains in the availability of UK-based investors with the technical knowledge necessary to evaluate and support deep tech ventures effectively.

Intellectual Property as a Competitive Moat

One of the defining characteristics of deep tech companies is their reliance on strong IP protection. Unlike conventional tech startups that often focus on software solutions with lower barriers to entry, deep tech ventures require significant investment in research and development (R&D) before they can bring products to market. As a result, patents, trade secrets, or other proprietary technologies become invaluable assets that distinguish these companies from their competitors and provide protection on the market.

A well-established IP portfolio serves several strategic purposes:

- Attracting Investors: Investors are more likely to back companies with clear IP ownership, as it mitigates risks associated with replication and competition.

- Facilitating Commercialisation: Patents and trade marks enable companies to license technology, form strategic partnerships, and create monetisation opportunities.

- Strengthening Market Position: Proprietary technologies provide companies with a sustainable competitive advantage, making it difficult for rivals to replicate their innovations.

The UK’s deep tech sector benefits from a strong academic foundation, with universities playing a crucial role in IP generation. However, balancing academic innovation with commercial scalability requires carefully structured IP agreements. Traditionally, UK universities have held significant equity stakes in spinouts, but recent trends indicate a shift toward more investor-friendly policies, allowing startups to retain greater control over their IP.

Challenges in Scaling Deep Tech and IP Management

Despite the clear advantages of IP protection, deep tech companies face several hurdles in managing and leveraging their intellectual assets:

- Complex Patent Landscapes: Navigating the patent process is time-consuming and expensive, requiring expertise to avoid infringement and ensure broad protection.

- Funding Gaps for Early-Stage IP Development: Many deep tech startups struggle with securing funds to file and maintain patents before achieving profitability.

- International Competition and IP Theft: Given the global nature of deep tech, UK firms must contend with IP risks from international competitors, particularly in strategic industries like semiconductors and AI.

The UK has a strong foundation in deep tech innovation, but unlocking its full potential requires a more sophisticated approach to intellectual property management. By addressing funding challenges, refining IP strategies, and fostering investor expertise, the UK can solidify its position as a global leader in deep tech commercialisation.

At Mathys & Squire LLP, we have a profound comprehension of industry standards, intricacies, and the unique challenges entailed in patenting cutting-edge inventions within the dynamic realm of deep tech. For more information on our specialist advice in this sector, visit our website or explore our dedicated Scaleup Quarter platform, tailored for companies ranging from start-ups to university spinouts.

Mathys & Squire have published a report on the use of the Unitary Patent system in the field of healthcare & life sciences, sharing the results of a survey on the patents granted to a selected number of applicants in 2023 and 2024 across four technical areas. The report was compiled by Partner Nicholas Fox and Associate Maxwell Haughey.

Good news! You have just heard that the EPO has decided to grant your healthcare patent application. You must now decide whether to allow the granted patent to be granted as a Unitary Patent in the member states participating in the Unitary Patent Court (UPC) or as a bundle of national patents and potentially file opt-outs to protect the national patents from central revocation in the UPC. You are aware of the various pros and cons of the UPC (see our opt-out brochure for further information), but what is everyone else doing? The pharmaceutical industry has been expected to adopt a cautious approach towards the UPC due to the value of individual patents and the potentially significant economic impact of a patent being revoked in multiple jurisdictions in a single court action. Does this mean that everyone simply opts their healthcare patents out of the UPC?

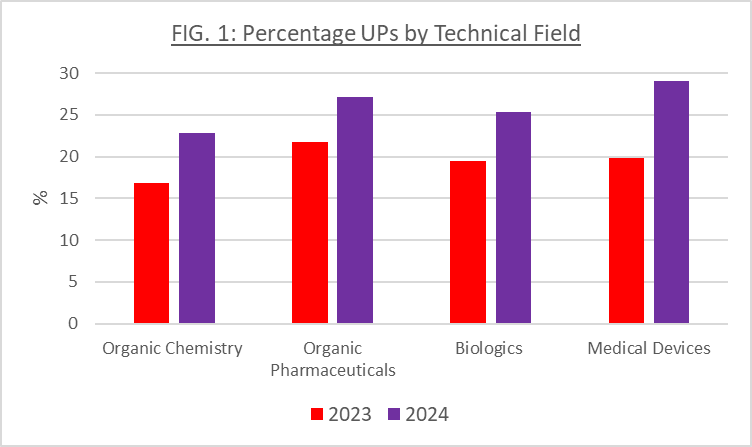

Percentage of Unitary Patents by technical field

The UPC entered into force on 1 June 2023, but it was possible to delay the grant of a European Patent from the beginning of the year until Unitary Patents might be granted. In practice this means that 2024 was the first full year when patent proprietors had the choice of obtaining Unitary Patents, even though, at least theoretically, any European Patent application found in order for grant since 1 January 2023 could have been converted into a Unitary Patent if a patent proprietor chose to do so.

It is perhaps unsurprising then that the percentage of European patents granted in 2024 in healthcare fields which ended up being maintained as Unitary Patents increased. This was true across all healthcare fields sampled. Use of the Unitary Patent was particularly high in the case of medical devices where approximately 30% of all patents granted in Europe in 2024 were maintained as Unitary Patents up from around 20% in 2023. As the graph below (FIG.1) illustrates significant proportions of granted European Patents end up as Unitary Patents subject to the jurisdiction of the UPC across all healthcare fields. Any suggestion that healthcare companies are opting all their patents out from the jurisdiction of the UPC is clearly wrong.

Figure 1: Percentage UPs by Technical Field

But what are specific applicants doing? To answer this question, we have sampled a range of applicants in each of the above technical areas. The sample we selected included most of the largest filers in the healthcare sector in addition to several applicants from related sectors such as agrochemicals and fine chemicals.

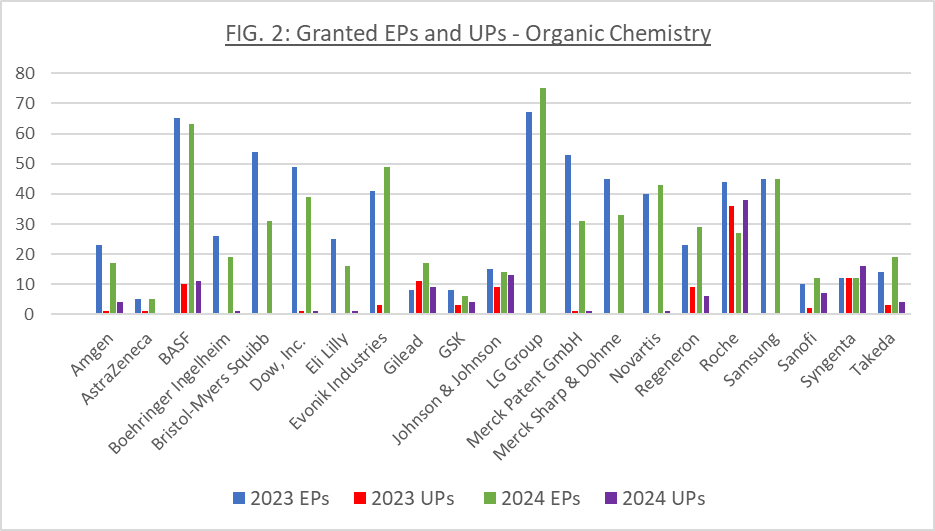

Organic Chemistry

FIG. 2 below shows the results of our survey for major patentees for patent applications relating to organic chemistry. In the graph below we show the numbers of European Patents (EPs) each applicant has chosen to maintain as national patents and the numbers of patents where the applicant has opted to have the patents maintained as Unitary Patents (UPs). The figure then further breaks these numbers down across patents granted in 2023 and 2024 to see if any change in behaviour of an individual applicant can be identified.

Figure 2: Granted EPs and UPs – Organic Chemistry

As can be seen in the graph above, a number of the significant filers in organic chemistry have engaged very little with the Unitary Patent system having either zero or low single digit numbers of Unitary Patents granted in 2023/24. For example, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, LG Group, Merck Sharp & Dohme (Merck & Co Inc.), Novartis, and Samsung all had no Unitary Patents granted in 2023, and at most had a single Unitary Patent granted in 2024. This group includes Bristol-Myers Squibb, LG Group, and Merck Sharp & Dohme who were among the largest filers for patents in this area of technology.

Where an applicant has been very selective about engagement with the Unitary Patent system, it may be the case that a or particular patents relate to technology for which a Unitary Patent is particularly suitable. Potentially, this may explain the single Merck Patent GmbH (Merck KGaA) Unitary Patent granted in 2024. That patent concerned a chemical process which involved multiple individual process steps which potentially could be conducted in different European countries for which protection via a Unitary Patent was particularly suitable.

Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novartis all had no Unitary Patents granted in the field of organic chemistry in 2023/24, and each had a single organic chemistry Unitary Patent granted in 2024. Potentially, these might also have been chosen as “test cases” for using the Unitary Patent system or for specific reasons relating to the individual inventions that the patents cover.

Other applicants have used the Unitary Patent system more widely, for example BASF, Gilead, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Syngenta, and Takeda.

Collectively, the figures indicate that different companies are taking very different approaches to the UPC and the Unitary Patent System. There is no uniformity of approach.

By way of example, Roche and Novartis are both multinational Swiss pharmaceutical corporations ranking in the top five global pharmaceutical companies by revenue. In the field of organic chemistry, Novartis converted none of their European Patents into Unitary Patents in 2023 and obtained only a single Unitary Patent in 2024. This compares with 40 and 43 organic chemistry patents in 2023 and 2024 respectively, where Novartis maintained their patents as a bundle of national rights. In contrast, Roche had 36 organic chemistry Unitary Patents granted in 2023 (compared to 44 European Patents maintained as a bundle of national rights), and this increased to 38 Unitary Patents granted in 2024 (compared to 27 European Patents maintained as a bundle of national rights). Hence, in contrast to Novartis who has yet to really engage with the Unitary Patent system, the majority of Roche’s organic chemistry applications are now being maintained as Unitary Patents.

The upward trend in the proportion of patents maintained as Unitary Patents which is apparent from Roche can also be seen in the figures for other applicants. Thus, for example, Syngenta also had a greater proportion of maintained as Unitary Patents in 2024 compared with 2023 so that in 2024 a majority of Syngenta’s patents in the field of organic chemistry were maintained as Unitary Patents rather than a bundle of national rights (16 Unitary Patents compared with 12 patents maintained as national rights).

Tentatively, this may suggest that some applicants are overcoming their initial caution about the use of the Unitary Patent system. However, as we only have two year’s data, and the data from 2023 is necessarily impacted by the introduction of the Unitary Patent half-way through that year (albeit with the option of selectively delaying patent grant where a proprietor really wished to obtain a Unitary Patent), it is probably too early to tell.

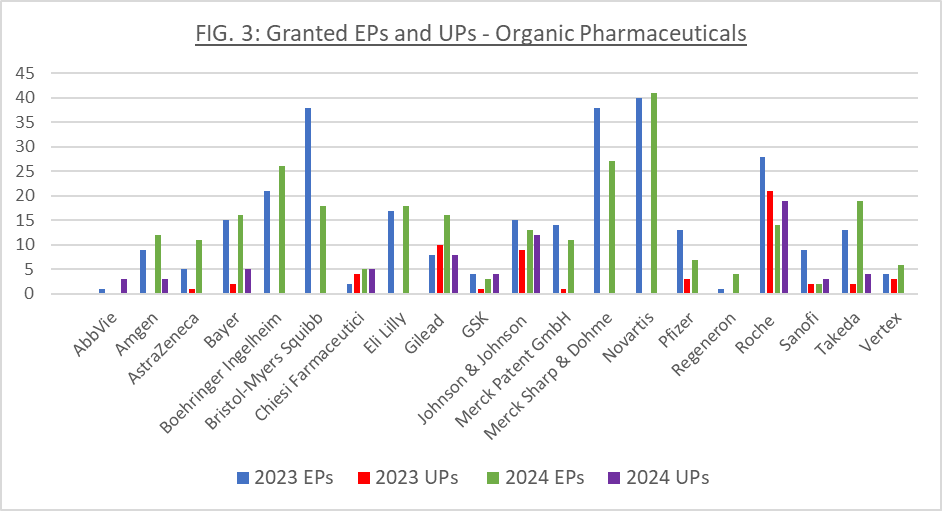

Organic Pharmaceuticals

Similar mixed signals are also shown in the numbers of patents converted into Unitary Patents by major filers in the field of organic pharmaceuticals shown below (FIG. 3)

Figure 3: Granted EPs and UPs – Organic Pharmaceuticals

AbbVie, Bayer, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Gilead, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, Roche, Sanofi, and Takeda all show relatively widespread uptake of Unitary Patents in the field of organic pharmaceuticals.

Chiesi Farmaceutici has chosen to convert the majority of their granted patents into Unitary Patents. This was the case both 2023 and 2024 when 4 and then 5 of Chiesi Farmaceutici patents were converted into Unitary Patents compared to 2 and then 5 patents which were maintained as national rights.

Although the sample size is small, AbbVie had no organic pharmaceutical Unitary Patents granted in 2023 (and a single patent maintained as a bundle of national rights), but 3 Unitary Patents granted in 2024 with no rights not being maintained as Unitary Patents.

Some applicants – Amgen, Bayer, Chiesi Farmaceutici, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, and Takeda – increased their use of the Unitary Patent system in 2024, However, others – AstraZeneca, Merck Patent GmbH, Pfizer, and Vertex – obtained Unitary Patents in 2023 but obtained no Unitary Patents in 2024. Whereas other major players in the field – Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, and Regeneron – have entirely avoided the Unitary Patent system for organic pharmaceutical inventions and have chosen instead to maintain all their European patents as bundles of national rights.

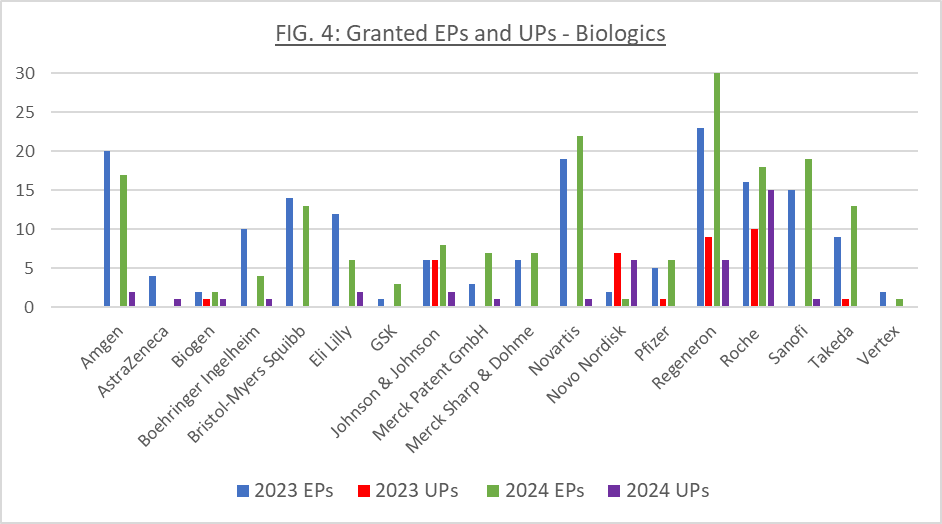

Biologics

FIG. 4 shows a similar analysis, this time in the field of Biologics.

Figure 4: Granted EPs and UPs – Biologics

Apart from Biogen, Johnson & Johnson, Novo Nordisk, Regeneron, and Roche, applicants generally seem to be more reluctant to use the Unitary Patent system for biologics. Of the applicants sampled, only Novo Nordisk obtained Unitary Patents for a majority of their granted patent applications (7 and 6 Unitary Patents in 2023/24, respectively compared to 2 and then 1 patent which was maintained as a bundle of national rights).

The greatest number of biologics Unitary Patents in our sample were granted to Roche. However, that was due to the higher number of patents that Roche obtained compared to the companies in the survey and still represented a minority of Roche’s biologics patents overall (10 and then 15 Unitary Patents in 2023 and 2024 compared with 16 and then 18 patents maintained as national rights in 2023 and 2024 respectively).

Bristol-Myers Squibb and Merck Sharp & Dohme converted none of their European Patents into Unitary Patents in 2023/24, despite these applicants being among the largest filers in this field. Whereas Novartis chose to maintain only a single European patent as a Unitary Patent in 2024, opting for national rights for 19 and then 22 biologics patents in 2023 and 2024 respectively.

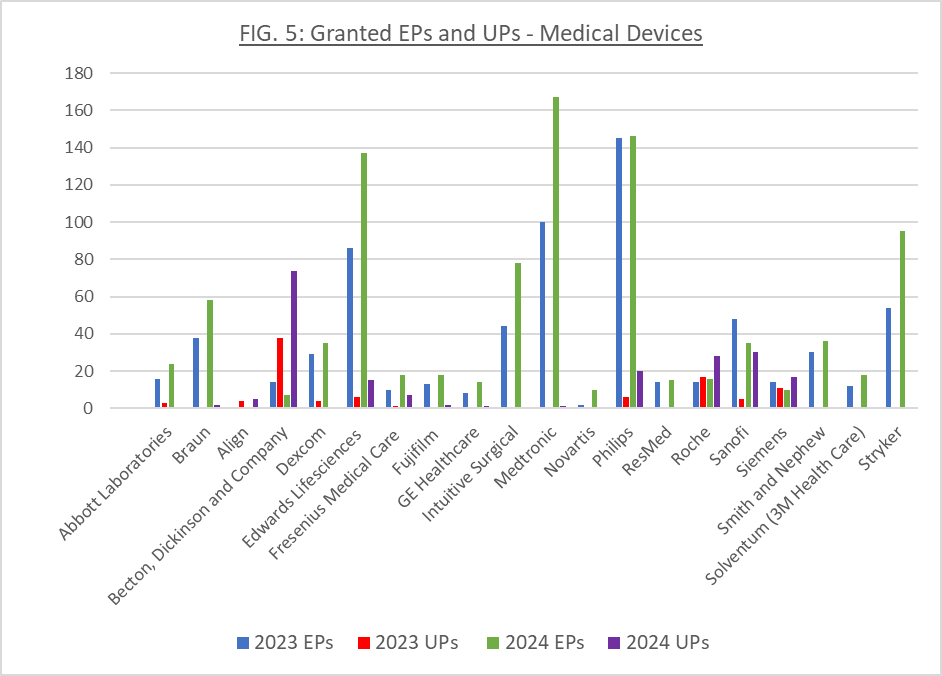

Medical Devices

Medical device applicants appear to be most divided in their adoption of the UPC (FIG. 5).

Figure 5: Granted EPs and UPs – Medical Devices

A significant number of applicants sampled have chosen to not to obtain Unitary Patents – see Intuitive Surgical, Novartis, ResMed, Smith and Nephew, Solventum (3M Health Care), and Stryker. This is particularly significant because some of the largest filers in the field of medical devices have chosen to take this approach.

Other applicants such as Abbott Laboratories, Braun, Dexcom, Fujifilm, GE Healthcare, and Medtronic, had either a single or low single digit number of Unitary Patents granted in 2023/2024, compared with significantly higher number of patents which were maintained as national rights. Of these applicants, all but Abbott Laboratories and Dexcom deferred their adoption of the Unitary Patent system for medical devices until 2024.

On the other hand, Becton, Dickinson and Company is notable for obtaining 38 medical device Unitary Patents in 2023 (compared to 14 patents maintained as national rights). Then in 2024, Becton Dickinson’s number of Unitary Patents was an order of magnitude greater than the number maintained as a bundle of national rights – 74 Unitary Patents compared to 7 maintained as national rights.

All of the medical device patents granted in Europe to Align were maintained as Unitary Patents in both 2023 and 2024. In fact, out of 49 patents granted to Align in Europe in 2023 (in all areas of technology), only a single patent (relating to a computer program) was not maintained as a Unitary Patent.

Other large filers including Edwards Lifesciences and Philips are choosing to obtain a mix of Unitary Patents and bundles of national rights. Although, both companies are opting for the Unitary Patent route for only a minority of their patents, in both cases the numbers of Unitary Patents granted doubled in 2023 compared with 2024. Potentially, this suggests that these companies chose not to delay grant of patents prior to 1 June 2023 just for the opportunity to obtain Unitary Patents which would cause the 2023 numbers to represent grants for only around half a year and that Edwards Lifesciences and Philips have been converting a consistent proportion of their Medical Devices patents into Unitary Patents since then.

Roche, Sanofi, and Siemens had a large proportion of their medical device patents granted as Unitary Patents in both 2023 and 2024 with between 45% and 65% of medical device patents for these three companies being maintained as Unitary Patents in 2024.

Sanofi and Roche provide an interesting example of how take up of the Unitary Patent is impacted by technical field. Looking at the figures for 2024, Sanofi converted a greater proportion of their medical device patents to Unitary Patents (46%) than was the case for organic chemistry patents (37%) or biologics (5%). Similarly, Roche’s figures vary significantly across different fields and in many cases are quite different from those for Sanofi with Roche obtaining Unitary Patents for 64% of their medical device patents, 37% of their organic chemistry patents, 58% of their organic pharmaceutical patents and 45% of their biologics patents.

Conclusions

As shown above, it is clear that at present different companies are adopting very different approaches to the use of the Unitary Patent system and that the approaches are nuanced depending upon the area of technology a patent involves. Widespread adoption of the Unitary Patent has not been limited to European-domiciled companies, with several US applicants now maintaining a significant proportion of patents in Europe as Unitary Patents.

It is clearly not the case that large companies choose to maintain all their patents as national rights, opting the patents out from the jurisdiction of the UPC to protect such rights from central revocation.

How those approaches develop further, only time will tell.

Organised by the General Assembly, the 26th of January is now recognised as the International Day of Clean Energy, enabling the opportunity to reflect and refocus on the collective goals of sustainability. In this article, Associate Jessie Harrison examines the current state of cleantech as we begin the new year.

As we enter 2025, climate change remains a hotly debated topic in global politics.

Last year signalled yet another record breaking rise in global temperatures, however only last week President Trump announced his intention to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement.

In Europe, the European Green Deal has placed pressure on the EU’s commitment to protect the climate. This includes goals of becoming climate neutral by 2050, and reducing emissions by 55% in 2030.

However, based on current trends, the United Nations has declared that the world is not on track to successfully achieve Sustainable Development Goal 7 – ‘Affordable and Clean Energy’ – by 2030.

It is increasingly clear that innovation and new cleantech technologies are essential to achieving these goals.

Cleantech relates to a diverse range of technologies that contribute to reducing our environmental impact. In the energy sector, this includes the likes of innovative renewables, long-duration energy storage, grid flexibility, and green hydrogen.

The Royal Academy of Engineering’s recent ‘State of UK Deeptech 2024’ report identified that, among the seven deep tech areas (manufacturing & materials; robotics, hardware & chips; networks; healthcare; frontier applications; energy; and AI & computing), energy exhibited the strongest growth in deal count between 2018 and 2023 with a compound annual growth rate of 12.9%. Investment in alternative energy sources is increasingly being seen to be both sustainable environmentally and financially, with growing public sector support. Indeed, S&P Global predicts that clean energy technology supply spending will surpass investments in upstream oil and gas for the first time in 2025.

In such an innovation-driven industry, intellectual property plays an important role in the successful development, protection, and commercialisation of new cleantech technologies.

This was clearly demonstrated in a 2024 report by the European Patent Office, EPO, which reported over 750,000 published international patent families in clean and sustainable technologies worldwide across a 25 year period up to 2021. In 2021 alone, almost 15% of all technological inventions disclosed globally related to clean and sustainable inventions.

As we look ahead for 2025, we can expect to see the demand for clean and scalable energy solutions surge, driven by the need to sustainably power the growing number of energy-intensive data centres supporting the AI revolution.

Quantum applications such as quantum computation and quantum cryptography are right at the cutting edge of high tech and as such offer near unlimited potential for innovation within the next decades. As of beginning of this year, Dr. Adrian Holzäpfel, researcher in the field of quantum networks with ten years of experience in the field, joins the Mathys & Squire Physics Team of Munich Partners Dr. Matthias Brittinger and Andreas Wietzke as a patent engineer and strengthens their expertise in this exciting sector.

During his academic career, Dr. Holzäpfel has studied under eminent experts in the field such as Prof. Immanuel Bloch and Prof. Nicolas Gisin and has performed his research activities at renowned institutions such as the University of Geneva, Technical University Munich and the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics (Nobel prize 2023).

We welcome Dr. Holzäpfel on board!

In modern culture, there is an increasing trend for people to opt for plant-based diets. There are many reasons for this, from increased awareness of climate change to personal concerns surrounding animal welfare or health concerns. For those that want to cut down on non-vegan products or trial the change in diet, Veganuary has become an opportune time to do so.

“Naturally” vegan recipes are expected to be made from raw ingredients, stripping back the meat and dairy that are normalised within most diets. However, with the ever-increasing switch to veganism, new technologies, brands, and products have surged, along with increased levels of innovation needed to provide desirable mass-market products.

One developing trend within the market is the replication of foods and ingredients that are widely popular in non-vegan form, such as meat and chocolate. Understandably, the convenience in substituting, rather than avoiding, non-vegan ingredients increases the accessibility of the diet and creates an easier transition between the two lifestyles.

This is clearly an increasing movement, evidenced by The Vegan Society passing their milestone of 70,000 product registrations in September 2024. However, this shift towards the re-design of existing products also necessarily requires technical innovation and, consequently, IP (intellectual property) protection for such innovations can be crucial to avoid others simply copying a product, especially for small businesses wanting to establish a foothold in the industry.

Intellectual Property and Vegan technology

In the past decade, the technology in the market has become increasingly groundbreaking, defying the expectations of what was originally thought possible for vegan eaters. The following businesses have demonstrated what is possible within the industry, but also the importance of protecting their work through IP.

Meat alternatives

Austrian brand Revo Foods have created ultra-realistic, whole-cut plant-based salmon using 3D food printing technology named “THE FILET – inspired by Salmon”. Their product is made from algae, pea protean and mycoprotein, with the extrusion technology allowing fats to be incorporated into a “fibrous protein matrix” that allows the seafood alternatives to achieve the typical flakiness of fish filets. They applied for a patent for their 3D print head with screw extruder called MassFormer.

Dairy alternatives

EVERY, a food tech company led by CEO Arturo Elizondo, have a foundational patent for their vegan egg product. Using precision fermentation, they can brew liquid egg white without the need for chickens. Recombinant ovalbumin is the primary protein found in egg whites and is responsible for its gelling, foaming and binding abilities. The company have been commended for how it ‘tastes, whips and gels like a chicken-derived egg white’.

Alternative cheese

South Korean company Armored Fresh have continued to shake up the dairy-alternative industry through their plant-based cheeses. They pride themselves on their patented technologies, including method of manufacturing vegetable lactic acid bacteria fermented almond milk and a method for producing plant-based cheese using almonds.

Danish food tech company Færm have also developed a method for making vegan cheese that closely mimics the original product. In February this year, they filed for a patent for the process for the manufacture of a legume-based food product, using their B2B company structure to provide their technology to food producers that want to utilise these methods.

‘Bee-free’ Honey

MeliBio, a US company, have applied for patent protection for their plant-based and ‘bee-free’ honey. This invention “replicates the compositional complexity of honey using solely plant-based ingredients”. The product is made with botanical extracts, sugars, and acids to replicate the taste and texture of real honey.

In such an innovative and growing industry, the role of intellectual property continues to play a vital role in supporting advancements that help expand the market. For smaller start-up businesses in particular, IP can provide a foothold for growth in the industry by protecting the core innovations on which their products are based.

If current trends continue then growing innovation in the vegan space can be expected, highlighting the value of strong IP protection to secure the value of innovations in the face of increasing competition.

Commentary by Partner Rebecca Tew and Managing Associate Adam Gilbertson has been featured in IAM, The Business Fashion Magazine, The World Intellectual Property Review and The Patent Lawyer Magazine as they discuss the rise in global patent filings for footwear inventions and Nike’s leadership in IP activity.

Read the extended press release below.

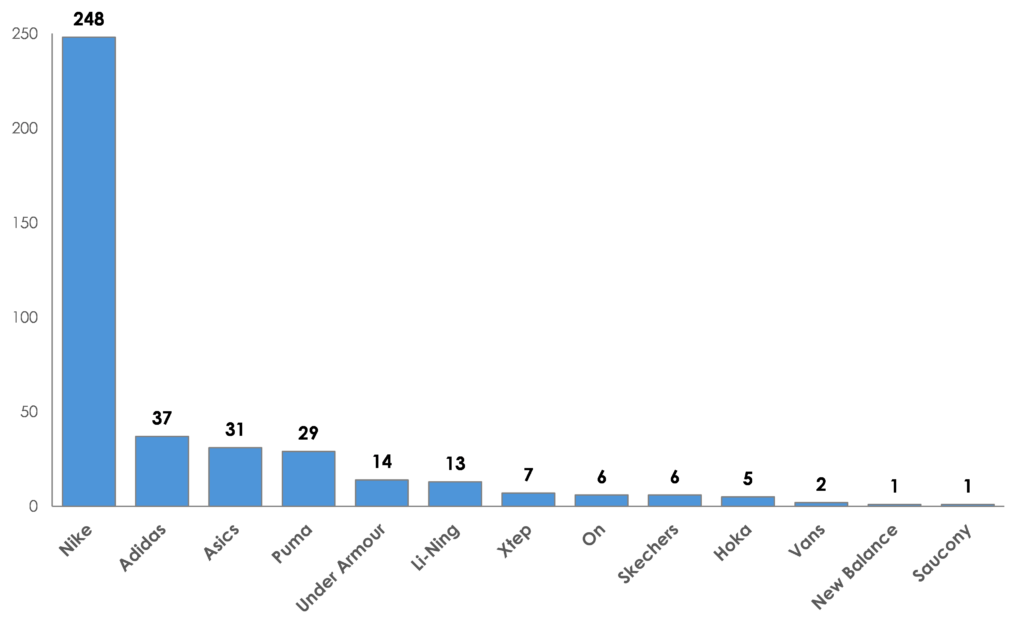

Nike is leading the way with global patent filings for footwear with approximately 250 applications published in the 12 months to June 30 2024 alone* – almost 100 more for the same period than all of its major competitors combined – as the world’s biggest shoe manufacturers compete in a ‘running shoe arms race’, says intellectual property law firm Mathys & Squire.

Nike’s nearest competitor for numbers of footwear patent filings is traditional German rival Adidas, with 37 patent applications publishing in the past 12 months*, amounting to just 15% of Nike’s total (see graph below).

The battle to develop and patent new technology for elite running shoes was triggered in 2017 by the launch of Nike’s first Vaporfly shoe, featuring a full-length carbon fibre plate for increased ‘rebound’ and efficiency when running, producing remarkable yet controversial results.

The resulting development of new shoe technologies has been credited with cutting the men’s marathon record by two minutes and the women’s marathon record by seven minutes since 2017.

The ‘running shoe arms race’ has heated up in recent years, as new entrants to the market, like Li-Ning and Xtep, are putting pressure on the established leaders.

This summer’s Olympic Games saw Nike competing with traditional rivals Adidas, Asics, New Balance and Puma to supply the most advanced shoes to athletes in events such as the marathon. However, this year’s Games also saw less-established brands like Swiss shoemaker On as well as Chinese manufacturers Li-Ning and Xtep supply high-profile runners. Both Chinese challenger brands had runners finish in the top ten of the men’s marathon in Paris in April 2024.

Rebecca Tew, Partner at Mathys & Squire, comments: “This may be the golden age of running shoe innovation.”

Adam Gilbertson, Managing Associate at Mathys & Squire, comments “The right shoe can now deliver a major step forward in a runner’s personal best. The introduction of carbon fibre plates and 40-millimetre foam outsoles has been a game-changer for runners.”

“Established manufactures like Nike have been patenting their shoe technologies for years, but newcomers to the market making these big innovations in running shoes should make sure that their investment in intellectual property is protected and they have a clear IP strategy. What can be patented should be patented in key territories to help prevent competitors copying key technology.”

Rebecca Tew adds that the rise of new running shoe technology has already started to generate patent disputes between footwear manufacturers. US-based running shoemaker Brooks recently sued German competitor Puma for patent infringement in the US, the latest development in a long-running intellectual property dispute between the two companies.

Patent applications for footwear inventions in the last 12 months include:

- A Nike patent filing for an automated shoe tightening mechanism, with a small motor in the heel;

- An Adidas patent filing for a football boot that can change shape based on data provided by sensors located within it; and

- An Xtep patent filing for a graphene-based rebound plate inside the sole.

Number of global patent applications for footwear inventions published in the past year – Nike is by far the most active patent filer

* Source: World Intellectual Property Organisation

As we draw to the end of another successful working year at Mathys & Squire, it is appropriate to take stock of our achievements throughout 2024.

It is a privilege to work with some of the brightest minds within the industry here at Mathys & Squire, and it has therefore been a pleasure to see our staff and partners recognised as IAM Strategy 300: Global Leaders, Managing IP: IP Stars, Managing IP: Rising STARS, The Legal 500: Recommended Individuals, IAM Patent 1000: The World’s Leading Patent Professionals and WTR 1000: Recommended Individuals. Our team is dedicated to achieving the very best for our clients, and it has been great to see our hard work and expertise recognised in this way. Indeed, this dedication has found considerable success this year in terms of a significant number of new clients.

This past year we have also celebrated many personal milestones in our team, including the promotions of Samantha Moodie, Edd Cavanna and Laura Clews into the partnership. Further, Alex Elder, Adam Gilbertson, Lionel Newton, Oliver Parish and Leonard Wright were promoted to Managing Associates.

As we continue to grow, we have welcomed many newcomers to the team. Some of those joining this year include Partner Matthias Brittinger, Managing Associates Chloe Flower and Markus Von Rudno, Associates Danielle Champagne, Emma Pallister and Greg Jones, and Technical Assistants Nathalie Richards, Alícia João, Adrian Salt, Thomas Mead, Sophie Wilson, Daniel Speed, Alexander Osborne, Craig MacGregor-Chatwin and Daniyal Khan. It is a pleasure to take on so many new joiners this year, and we look forward to growing our team and welcoming even more staff in 2025.

We have shown once again the excellence of our internal work processes and management systems through the achievement – for the 8th consecutive year – of our ISO 9001 & 14001 certifications.

Within our community, it has been great to give back, particularly through the charitable donations of the firm. We are pleased to share that we have raised over £3,300 through fundraising and match funding, with Southwark Food Bank (an initiative led by Technical Assistant Nathalie Richards), Movember and Macmillan Cancer Support a selection of the charities that have been positively impacted by our donations.

We have also invested £22,000 in improving diversity, inclusion, social mobility and wellbeing within the IP industry. Through our continued partnership with Career Ready, a non-profit organisation dedicated to bridging the gap between education and employment, we have a 12-month mentorship programme in which our colleagues guide their mentees through the early stages of their career journeys. We have also sponsored two students to go through the In2STEM programme led by In2Science, an initiative which encourages the pursuit of science, technology, engineering and maths based employment by increasing accessibility in these sectors. Finally, we have signed the ’Leaders’ Pledge’ of IP inclusive to underline our genuine commitment to enact positive change within our industry. This includes signatures from Paul Cozens, Caroline Warren and Alan MacDougall.

This year more than ever, we have seen the rewards of our focus on ensuring that our values are at the forefront of all that we do. We strive to ensure that we are Better Together by treating everyone fairly, encouraging diversity, and collaborating effectively within and across our various areas. And by Empowering one another there is always a wide breadth of opportunities for positive change, personal development and progress. The very bedrock of Mathys & Squire is our Clients First approach, upon which our best in class technical, legal and professional expertise is founded. We are indeed fortunate to have such an exceptionally talented team at Mathys & Squire.

Reflecting upon what the firm has achieved this year fills us with an immense sense of pride. Now, looking forward to 2025, we can be more than confident that we will bring this same strength to the new year – a year that marks no less than the 115th year anniversary of Mathys & Squire.

Best Wishes,

Mathys & Squire Managing Partners

In the UK, it is estimated that 100,000 people suffer from strokes each year, equivalent to one stroke every five minutes. Research from the NHS demonstrates the life-changing aftermath they can have, with over 50% of survivors affected by a long-term disability.

Time is a crucial factor for preventing enduring symptoms as it is estimated that a patient loses 2 million brain cells every minute during a stroke. With the devasting impacts of this disease clear, it is not surprising that innovative technologies are being sought to help NHS staff and stroke centres decrease their response time and improve patient outcomes.

The Brainomix 360 Stroke AI tool is a fantastic example of how innovative technologies can unlock improved treatment delivery in the health care sector.

Brainomix launched as a spin-out from the preclinical stroke lab at the University of Oxford in 2010. Their advanced AI algorithms assist in the diagnosis and understanding of each patient’s condition by applying proprietary image processing techniques to brain scans to provide real-time interpretation, enabling more patients to get the right treatment at the right time.

For the NHS, the benefits unlocked by the Brainomix 360 Stroke technology have been vital.

Firstly, analysis of the impact of Brainomix’s 360 Stroke AI tool within the NHS demonstrated a 50 minute reduction in medical treatment time. Especially important in the field of stroke care, reducing the time taken to analyse and interpret test results enables the appropriate treatment for each patient to be identified and delivered at a much faster rate. Not only can AI technologies help in the display and interpretation of results but, as highlighted by David Hargroves (NHS England’s National Clinical Director for Stroke), it can help the confidence of NHS staff in supporting clinical decisions made in a high intensity, time pressured environment.

Secondly, the use of AI has enabled an increase in patient treatment by mechanical thrombectomy (MT). Mechanical thrombectomy is a time-critical intervention which helps patients by reopening a blocked blood vessel in the brain, significantly reducing the risk of long-term stroke impacts. As a result of rolling out the Brainomix 360 Stroke AI tool, it was demonstrated that patients were 70% more likely to receive mechanical thrombectomy (MT) than before.

In addition, through a faster understanding of the need of each patient, communication between hospitals has strengthened. As each patient is promptly assessed, they can be appropriately transferred, getting each patient the right help in the right location with ease.

Today, every stroke centre in England (107 in total) has now rolled out the use of AI in their practice, with research suggesting it now assists 80,000 people who have a stroke every year.

The adoption of innovative technologies in the field of stroke treatment has already demonstrated its potential for meaningful impact, greatly improving patient outcomes and streamlining the delivery of treatment. Yet, there still exists huge opportunity for AI technologies to revolutionise the delivery of medical treatment in the healthcare sector.

Mathys & Squire is proud to be working with Brainomix in the pursuit of protecting their innovative platforms and proprietary technologies.

If you have any questions about pursing patent protection for AI-based technologies in the healthcare sector, please reach out to a member of our team.

We are delighted to announce that we have successfully passed the ISO 9001 & 14001 audit for the 8th year.

ISO certifications are led by the British Assessment Bureau in order to assess and examine businesses, showcasing their dedication to excellence in work processes and management systems.

Our first certification, Quality Assurance (ISO 9001), demonstrates how the firm meets the globally recognised standards, showing our commitment in providing a high level of customer service, delivering consistent performance and continuously improving.

The second certification, Environmental Management (ISO 14001), recognises our commitment to improving environmental performance through efficient use of resources and reduction of waste. From this, it is clear we are taking meaningful steps forward to reducing our carbon footprint.

We are proud to be an environmentally aware firm, and are pleased to be able to formalise our progress and gain recognition for our commitment to delivering a first-class service to our clients.

To find out more about ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 click here.