The UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) has published a new guidance following the pivotal ruling in SkyKick UK Ltd and another v Sky Ltd and others (SkyKick). The updated Practice Amendment Notice 1/25 refines the examination practices at the IPO and outlines the implications of the judgement for new applicants when filing specifications of goods and services. Such changes are to come into effect immediately.

Background

Section 3(6) of the UK Trade Mark Act 1994 prohibits registration of a trade mark “if or to the extent that the application is made in bad faith.” What constitutes ‘bad faith’ is not legislatively defined, however, has been interpreted by the courts. Most notable is the recent Supreme Court Judgement in SkyKick following a long-running dispute between the parties. While the court confirmed a finding of infringement of Sky’s trade marks by SkyKick, it was found that Sky’s registrations contained excessively broad specifications across a range of goods and services for which there were no genuine intention to use the mark, and therefore, partially invalid on bad faith grounds.

Under the new guidance, examiners will now actively consider whether a specification is “so manifestly and self-evidently broad that a bad faith objection should be raised.” It follows that that certain applications claiming all 45 classes or all goods/services in those classes for example, will now automatically trigger an objection.

Looking Ahead

As a general rule, applicants should ensure that their specifications include goods and services which represent “fair and reasonable claims in the context of their business.” Going forward, applicants should exercise caution when filing a vast number of goods and services across a broad range of classes, or when using broad terms such as clothing, software, entertainment etc. That said, a pragmatic balance needs to be struck to not file too narrowly to restrict opportunities for business expansion.

Should an objection be raised by an examiner, applicants must be prepared to explain the commercial rationale behind the goods/services concerned. Paragraph 15 of the PAN 1/25 provides a 2-month period for a response. If the examiner refuses to waive the objection, applicants will still have the opportunity to be heard and to appeal. If the applicant genuinely is going to offer all goods/services applied for and can provide a justifiable commercial rationale and reasoning, we would expect the objection to be overcome.

Finally, opponents and cancellation applicants are also encouraged to be mindful of the changes above. as relying on broad specifications may lead to counterclaims from the other side on bad faith grounds. This has already been happening since the SkyKick judgement though in practice, but it is worth a reminder that this is possible as part of the proceedings before the UKIPO.

Mathys Comment

This is not an unexpected development by the UKIPO, but it will cause challenges for applicants who are used to filing with broad specifications (both in terms of classes and goods within the same class). Whilst the UKIPO does have an effective online tool to assist with drafting specifications, given the drafting of such defines your protection (and scope to challenge moving forwards) we would certainly recommend seeking advice from one of the Mathys trade mark team to ensure a) your specification covers you now (and moving forwards) and b) will ideally not trigger an objection.

Between August and October 2023, the UK government launched its Second Transformation Consultation to support the UKIPO in delivering improved digital services. One key proposal is to change, or potentially abolish, the use of series trade marks.

Series trade marks are a unique feature of the UK system, allowing applicants to register up to six similar marks (e.g. logos in different colours, differences in capitalisation, minor variations of spelling) in a single application at a reduced cost. This option is not available in other systems such as the EUIPO or the Madrid Protocol. Applicant’s were able to apply for up to six marks in a series, in accordance with Section 41(2)(a) of the Trade Marks Act 1994:

”A series of trade marks means a number of trade marks which resemble each other as to their material particulars and differ only as to matters of a non-distinctive character not substantially affecting the identity of the trade mark.”

Series marks are particularly useful when a logo appears in multiple colour variations or has several common adaptations, as they extend protection to all versions. They are also advantageous when a logo includes variations in visual elements, such as differences in colours, icons or stylised text, depending on the context. Overall, series marks offer broad legal protection while allowing for flexibility in how the logo is used across different scenarios. Despite variations in the marks, a series trade mark ensures consistency in the brand identity, protecting the core mark while enabling adaptation for numerous applications.

However, on 10 April 2025, the UKIPO published the consultation report and found that many applicants find series marks confusing. Specifically, 65% of applications are filed without professional representation, and in 2022, 39% were objected to for not meeting the legal criteria for registering a series of trade marks. This can lead to additional costs for applicants who need to file new applications. However, applicants would need to at least double filing costs without the series mark being available if they wanted to file more than one variant of their mark, so it is difficult to see how not having the series mark would lead to a cost saving on the whole. Furthermore, the UKIPO is of the opinion that series marks provide limited additional legal protection, reducing their overall value for money.

While this is arguable as we have found series marks to be a very beneficial tool for brand owners when used correctly, we do acknowledge that the UKIPO’s approach to assessing the validity of a series trade mark application is strict and any variations as to the distinctiveness of the mark to the point where the overall identity and impression of the trade mark has changed, even due to variations of colour, the application can be objected against or refused.

Professional representation is key to making the most out of the series system in the UK and it is somewhat disappointing that the UKIPO have decided to phase these marks out. While existing series marks will remain valid, the UKIPO expects to phase out the option for new applications once its new digital trade mark service launches. A specific date for this change has not yet been confirmed. If you have any marks which could constitute a series it would be beneficial to file them sooner rather than later.

In addition to developments at the UKIPO, as part of its digital transformation, the UKIPO will soon make trade mark and design documents, such as examination reports, available online for the first time through the new One IPO Search tool, bringing patents, trade marks, and designs into one unified platform.

Government response to the Second Transformation Consultation report below on series trade marks applications and more here.

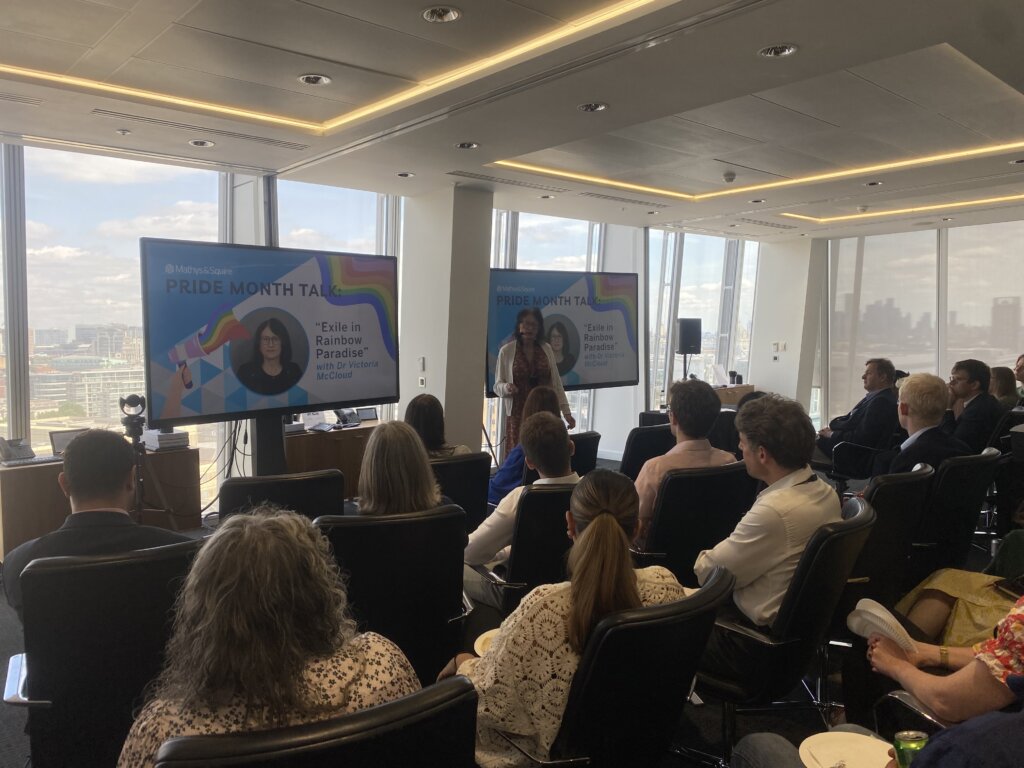

On Wednesday the 25th of June 2025, Mathys & Squire hosted Dr Victoria McCloud, former Judge in the High Court and advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights, in our London office in honour of Pride Month.

From a young age, Victoria discovered a fascination with computers, as well as an acute awareness of human behaviour and interactions – experiencing life through the eyes of a girl as a registered boy at birth. These interests motivated her to pursue a degree in Experimental Psychology and a doctorate in the computational aspects of human vision.

After graduating, she practiced as a barrister, when she came out as a transgender woman, and then went on to be the youngest and first (and only) transgender Master in the UK High Court of Justice.

In 2024, she resigned as a Judge, feeling that there was no longer a place for her as a trans person in the UK court. Now, Victoria McCloud is a freelance public speaker, author and media commentator, raising awareness for issues affecting the LGBTQIA+ community and speaking directly from her experience as a trans woman.

Last year, she featured on the Dow Jones News “Pride of Finance”, whilst this year she reached first place in the Independent Newspaper Pride List and featured in Attitude Magazine’s 101 LGBTQ+ trailblazers 2025.

Victoria gave an educational and engaging talk which followed the timeline of her life whilst delving in to important topics, such as the nature of the UK legal system, changing attitudes towards gender, and her recent move to the “rainbow paradise” of Ireland. She also discussed the topical issue of how the rights of transgender and gay people are under threat in light of the recent Supreme Court Ruling. It was enlightening to gain an insight from someone with a deep understanding of both the law and the trans experience.

We are delighted to announce two new Partners and two new Managing Associates.

Mathys & Squire is delighted to announce a new round of senior promotions to its London office.

Harry Rowe and Dylan Morgan have been appointed as Partners. Helen Springbett and Tom Bosworth have been promoted to Managing Associates.

These appointments recognise their valuable contributions and leadership across Mathys & Squire’s trade mark, design and patent teams.

Harry Rowe is appointed Partner in London

Harry has over a decade of legal expertise specialising in trade mark law issues facing multinational corporations and SMEs. He works across a range of sectors including financial services, life sciences and automotive. Harry has a proven track record handling disputes, prosecutions and enforcement, including litigation. He is a recommended lawyer in the latest edition of The Legal 500.

Dylan Morgan is appointed Partner in London

Dylan has considerable experience drafting and prosecuting UK and European patents, managing global portfolios, and advising on infringement, licensing and IP strategy. He was previously an engineer at the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory. Dylan holds a master’s degree from the University of Cambridge, specialising in aerospace engineering.

Helen Springbett is appointed Managing Associate in London

Helen has extensive experience in patents and designs, specialising in the physics, mechanical engineering and materials science sectors. She has a wealth of expertise in medical informatics and devices, mechanical devices and nanotechnology. Helen holds a PhD in materials science from the University of Cambridge, specialising in the characterisation of quantum dots.

Tom Bosworth is appointed Managing Associate in London

Tom has significant experience in patent drafting, prosecution, and EPO oppositions and appeals. He specialises in cell and gene therapy, vaccines, antibodies, and genomics technologies. He holds a PhD in cardiovascular sciences from the University of Manchester. Tom previously worked in the biotechnology industry prior to his PhD.

Martin MacLean, a Senior Equity Partner at Mathys & Squire, says: “These promotions have all been well earned. Harry, Dylan, Helen and Tom are incredibly talented attorneys whose drive and hard work are an immense asset to our firm.

“We take pride in nurturing and developing our talent, and all four have consistently delivered the highest-quality work to our clients. I’m fully confident they will continue developing their practice and enhancing their expertise.

“We are very excited to welcome Harry and Dylan into our Partnership. Both will help lead our firm on a strategic level and play a crucial role in our growth plans.”

This June marks Pride month, a time to celebrate the talent, creativity and innovation demonstrated by members of the LGBTQIA+ community, and reflect on the challenges and discrimination many would have faced particularly in their professional careers.

Whilst there has been progression over the years, it is no secret that we still live in a time where many are unable to feel empowered as their authentic self. Therefore, by acknowledging the following engineers and technical experts, we not only honour their scientific contributions, but also highlight the importance of visibility and representation. The following people serve as powerful role models to the next generation, inspiring and empowering others to pursue their ambitions with confidence and pride.

Frank Kameny (1925-2011)

Frank Kameny had a passion for astronomy from a young age, majoring in Physics in his degree at Queens College and completing his PhD later at Harvard University. He worked for the Army Map Service, working to develop and analyse astronomical maps during the conflict between the Soviet Union and the US. Unfortunately, he was fired shortly after it came to their attention that he identified as gay, and with his security clearance removed, he was no longer able fulfil this passion. In 1961, he became the first to petition the Supreme Court with a discrimination claim based on sexual orientation, and committed to being a LGBTQIA+ activist, organising protests and assisting others with their discriminatory law suits.

Sally Ride (1951-2012)

On 18 June 1983, Sally Ride became the first American woman to travel to space, as she completed her journey on the Challenger’s STS-7 mission. Beyond her vital work at NASA, she founded Sally Ride Science, a non-profit organisation which encouraged women to pursue STEM subjects. Sally had preferred to keep her identity as part of the LGBTQIA+ community private until after her death, in which she posthumously revealed that she had an intimate relationship with her working partner, Tam O’Shaughnessy. In 2013, the year after her passing, she was honoured with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama.

Edith Windsor (1929-2017)

In the 1960s, Edith Windsor was a pioneering computer programmer who exceeded in her career. She famously worked at IBM for 16 years, reaching the greatest possible position as a Senior Systems Programmer, a feat even more impressive as a woman in this era. She was an LGBTQIA+ activist and played a vital role in the Supreme Court case Windsor vs United States, in which she famously argued for a tax refund after the passing of her partner, which led to the court granting more benefits to same-sex couples. People often reference this as a turning point for same-sex couple in the US, and she is therefore remembered with the utmost respect. In 2013, she was a finalist for TIME magazine’s Person of the Year, and was described by TIME as “the matriarch of the gay-rights movement”.

Nergis Mavalvala (1968-)

Nergis Mavalvala is an astrophysicist who played a key role in the discovery of gravitational waves from the collision of two black holes. In his theory of general relativity, Albert Einstein had theorised this phenomenon, but it was Nergis and the rest of her team who were able to confirm this. Nergis has always been thoroughly committed to her education, completing her doctorate degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Astrophysics. She refers to herself as an “out, queer person of colour”, and dedicates herself to challenging discrimination in STEM.

Audrey Tang (1981-)

Audrey Tang is a computer scientist who first brought attention to their technological skill in 2014 during the Sunflower Protests in Taiwan as an open-source hacker, by helping to stream videos of the movement across the country. Tang later joined the ministry at 35, becoming the first ‘Digital Minister’ and Taiwan’s first transgender and non-binary minister. They have since been involved in revolutionary programmes, such as an educational initiative that helped equip young people with skills to identify fake news stories, as well as developing the ‘Mask Map’ during COVID-19, an online application which showed where masks were available to purchase during a national shortage.

At Mathys & Squire, we believe it is essential that everyone feels empowered to bring their full, authentic selves to work. We are deeply committed to fostering a workplace culture where diversity is celebrated, inclusion is prioritised, and everyone feels respected, valued, and supported.

Click here to read more about our Diversity & Inclusion policies.

IPSS Electra Valentine has co-written an article highlighting the meaning of Juneteenth as part of her role on the IP & ME committee at IP inclusive.

Yesterday marked Juneteenth, a significant day commemorating the end of slavery in the United States. It serves not only as a moment to celebrate freedom, but also an important opportunity to deepen our understanding of Black history, culture, and the ongoing journey toward equality.

The article examines the historical context of this day and considers its relevance and significance for IP professionals based in the UK, highlighting how its themes of freedom, justice, and inclusion resonate within the industry today.

Click here to read more.

We are proud to announce the appointment of Lyle Ellis as head of Mathys & Squire Consulting, the consulting arm of our firm.

Lyle joins Mathys & Squire from KPMG Law, where he served as Senior Manager in the IP Advisory division, advising startups and multinational corporations on IP strategy and operational management.

Lyle brings over 20 years of extensive experience in intellectual property management, strategy, and advisory services. Prior to KPMG, Lyle had a distinguished career as a UK and European Patent Attorney in-house at Vodafone.

Mathys & Squire Consulting advises clients on how they can maximise value from the intellectual property they produce and own. Specialist IP services within that group include IP audits, outsourced IP management, advising on contracts and licenses, and IP valuations.

Lyle brings a deep background in legal and commercial IP strategy, including IP risk management, threat assessment and value maximisation to Mathys & Squire Consulting.

His proven expertise in developing and managing IP portfolios will contribute significantly to the firm’s growth and capabilities, enhancing its ability to provide clients with high-quality, strategic IP advice.

Alan MacDougall, a Senior Equity Partner at Mathys & Squire, says: “We are thrilled to welcome Lyle to the team. His unparalleled expertise in IP will strengthen our capabilities and accelerate our growth. His leadership will undoubtedly enhance our ability to provide exceptional service to clients.”

Lyle Ellis says: “I’m excited to join Mathys & Squire and work with its talented team of consultants and other IP specialists. Mathys & Squire has a fantastic reputation as a law firm and it is also doing some really innovative and important work in the IP consultancy field. I’m looking forward to working with the team to build on that growing track record.”

The Enlarged Board of Appeal has issued a decision confirming that the description and drawings shall always be consulted to interpret the claims when assessing the patentability (i.e. novelty and inventiveness) of an invention.

In their decision on case G1/24, issued on 18th June 2025, the Enlarged Board of Appeal heard facts and arguments concerning a worrying divergence which had occurred in the case law, whereby questions of claim construction and interpretation had sometimes been made with reference to the description and drawings, and other times in isolation of the remainder of the specification. Oftentimes, this difference depended on the clarity of the claims, with it being generally agreed that the description and figures could be considered if the claims were unclear or ambiguous but potentially not otherwise.

In this new decision, the Enlarged Board have rejected any premise that the resources of the patent which are available to assist in interpreting the claims may depend on the clarity of the claims themselves, stating that: “To regard a claim as clear is in itself an act of interpretation, not a prerequisite to construction.” Thus, the decision of the Board fundamentally changes the impact of claim clarity on the assessment of claim construction, harmonising the approach for all claims.

The Board’s decision also serves to harmonise the approach of the EPO with that of the UPC and European national courts, with the Board confirming that their decision was consistent with recent decisions of the UPC, and acknowledging a need and desire for further harmonisation.

This decision is likely to be broadly welcomed by many users of the EPC due to the certainty it provides as to the scope of the patent teaching which may be relied upon for claim construction purposes. By bringing the EPO approach into greater conformity with that of the UPC and national courts, the EPO also increases its ability to grant and maintain robust patents. Alongside these benefits, care should be taken to consider closely the impact of any amendments or differences that may have arisen between the claims and the description or figures of an application to ensure that undesirable constructions are not arrived at which may impact upon the scope and/or patentability of the claims.

If you have any questions as to how this decision may impact on your IP strategy, please reach out to your usual contact at Mathys & Squire, or get in touch through a general enquiry and we would be happy to help.

Clean energy beamed down to Earth. Exotic semiconductors and novel pharmaceuticals manufactured in microgravity. A base on the moon. Asteroid mining. Satellite recycling. Data server farms in orbit. Space tourists.

A new horizon study Space: 2075, issued by the Royal Society, sets out a vision of potential developments in space over the next 50 years. These could be as consequential, the report says, as the Industrial Revolution of the 18th century or the digital revolution of the 20th. But as space

becomes increasingly commercialised, is the present patent system up to the task?

The state of the UK space industry

The UK space industry is worth over £16 billion annually and employs more than 45,000 people. Almost every year since 2000 has seen the incorporation of at least 50 new space-related companies in the UK.

That said, the UK could do better. The UK spends less on space than some similarly-sized nations – less as a % of GDP than France, Italy, Belgium, Germany, as well as even Switzerland and Norway. Attempts to spur the industry have had mixed results. The UK has established over a dozen space innovation clusters, but none of the seven UK spaceports first legislated for in 2018 have as yet resulted in a successful launch.

Meanwhile, for reasons both geopolitical and economic, international competition in the space sector is increasing. National pride, industrial and defence policies have led to approximately a dozen countries now having launch capability. At the same time, the cost of getting material into orbit has fallen. In the last decade, the cost of launching a 1kg payload into low-Earth orbit has fallen from around £15k to £1k. This has consequently lowered a major barrier for new entrants.

It is clear that the UK space industry needs a boost. And indeed, the Royal Society report identifies the need to stimulate the scale-up of UK space SMEs. One recommendation for achieving this is through increasing the confidence of the finance sector. For example, using technical means to reduce the risk of satellite collisions could reduce insurance costs.

What is missing from the report is a discussion of another form of incentive: patents. Investors looking to back a company in an innovation-driven industry such as space will be wanting to know whether they have sufficiently protected their intellectual property to ensure successful commercialisation.

Patent law and the impact of ‘space law’

Here on Earth, most countries of the industrialised world operate a well-established patent system, the foundations of which can be traced back to the Paris Convention for the protection of industrial property of 1883. Although patents are inherently territorial, which is to say they operate at a national level, various international agreements have sought to allow for some degree of interoperability.

However, patent law becomes less clear above the Kármán line, the 100km altitude widely accepted as the beginning of space. Part of the problem is a certain tension between terrestrial patent law and what might be termed ‘space law’, originating in a handful of international agreements drawn up in the 1960s and 70s. The idealistic tone of these early agreements, seeking to codify the peaceful exploration of space, can be seen in how they constrain property rights. The agreements prohibit national appropriation in an attempt to ensure space remains the “common heritage of mankind.”

This is not to say that ownership of IP in space is entirely impossible. Much of the concern of these treaties was the ownership of physical rather than intellectual property. In other words, whether a nation, corporation or individual could lay claim to a celestial body (generally, no). It has subsequently been argued that the treaty language is ambiguous. For example, it is unclear whether it would apply to processed material extracted from such bodies by mining activities.

Who owns innovation beyond Earth?

There is potential for applying ostensibly Earth-bound laws, including those directed to intellectual property, in space. The potential arises from the way the Outer Space treaty (1967) and the registration Convention (1965) allow for jurisdiction over an object launched into space or on a celestial body to reside with the state which launches the body or the state from which the body is launched. Some later agreements, typically multilateral ones in respect of specific endeavours, acknowledge jurisdiction over IP more directly. For example, the ISS agreement (1998) includes specific provisions regarding protection of IP on the international space station, assigning jurisdiction and territory of each station module according to its state of origin. Others, such as the Artemis Accords (2020), merely acknowledge the need for relevant IP provisions without providing any further legal structure.

At present, in much the same way as an “international patent” does not exist, neither are there any provisions for – or immediate prospects of – a “space patent.” And while some countries, notably the US, have explicitly sought to extend the coverage of their national patent law to inventions made in space, many others including the UK have no such provision. This could arguably lead to the situation of a space object being considered to be in the jurisdiction of the UK by virtue of being launched from the UK, yet outside the territorial scope of UK patent law.

How can space innovations be best protected?

The applicability of patent law in orbit (or beyond) remains untested and proving infringement in space is unlikely to be straightforward. In the absence of specific contractual agreement, the best option at present appears to be, rather ironically, to aim primarily for terrestrial protection i.e. to seek a patent monopoly that would be infringed on Earth.

To that end, a careful analysis of what activities are being conducted on Earth needs to be undertaken. And for a product being made in orbit, where it is to be returned to on Earth.

The patent filing strategy also requires careful consideration, not least because territorial decisions made relatively early in the patenting process become locked-in for the duration. This requires due diligence to identify competitors: where relevant space objects are registered (the ‘flag of convenience’ issue) and launch locations both present and future.

So, can the present patent system cope with potential developments in space over the next 50 years? For the next short while, with careful handling, perhaps – but over the long term it seems some updates will be inevitable. The Industrial Revolution led to a substantial overhaul of patent laws; the digital revolution was accompanied by a flood of patent filings pushing the boundaries of patent laws. Would we expect the space revolution to be any different?

In celebration of our 115th anniversary, we are proud to have planted 115 trees in partnership with Trees for Life. Each tree symbolises a year of growth, resilience, and our continued commitment to building a better, greener future.

As we celebrate our 115th anniversary, we have a valuable opportunity to reflect on our history and acknowledge the people, milestones and moments that have helped shape our firm. It is also a time in which we can look ahead with purpose, recognising the vital role that we play in shaping a more sustainable world and promoting positive change for future generations.

At Mathys & Squire, we firmly believe that protecting the environment is not just a responsibility, but a necessity. Through initiatives like this, and through the continued integration of environmentally conscious practices in our day-to-day operations, we are committed to contributing to a more sustainable world.

Click here to find out more about our CSR initiatives.