Gene therapy is revolutionising the field of molecular medicine and the capabilities of therapeutic approaches. Recent developments demonstrate the potential for gene therapy to address some of mankind’s most devastating diseases, unlocking previously unfathomable solutions which could transform people’s lives. As innovation accelerates, strong patent protection is essential to navigate rising IP disputes and safeguard gene therapy advances.

Introduction to gene therapy

Gene therapy is a medical technology which mitigates or eradicates the symptoms of diseases by transferring genetic material to a patient or correcting genetic defects. It can be achieved in several ways.

- Gene replacement delivers a functional copy of a gene to compensate for a defective one, making it especially useful for recessive monogenic diseases.

- Gene silencing reduces the expression of harmful genes, often through RNA interference or CRISPR–Cas13 targeting of pathogenic mRNA.

- Gene editing directly modifies endogenous DNA using tools like CRISPR-Cas9, zinc-finger nucleases, TALENs, or newer base and prime editors. These technologies allow targeted correction or disruption of disease-causing genes with increasing precision.

The genetic material can be delivered to the patient via viral and non-viral systems. For example, viral vectors such as adeno-associated virus (AAV) are preferable for in vivo use due to their safety and tissue specificity. Non-viral systems (such as lipid nanoparticles and polymer-based carriers) usually offer improved safety and flexibility but typically lower delivery efficiency.

Today, gene therapy is applied to an increasingly wide set of diseases. An analysis of patent activity shows that oncology accounts for roughly 32% of the gene therapy market, followed by rare genetic disorders (27%), cardiovascular diseases (15%), and neurological disorders (12%).

Recent innovation in the field

Whilst gene therapy is still predominantly limited to research and clinical trials, with over 250 clinical trials running in Europe and only around 20 therapies on the market, broader clinical adoption is getting closer.

The UK’s Medicine and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) approved the world’s first CRISPR-gene therapy in November 2023 and it is now available on the NHS in England. Named CASGEVY®, the drug (exagamglogene autotemcel) uses CRISPR-Cas9 to alter human stem cells to produce functional rather than defective haemoglobin, treating sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia.

Other advances are also setting the field into motion, such as innovations in delivery methods. Among these, AAVs are emerging as a major force in the gene therapy market. In June this year, Barcelona-based startup, SpliceBio, secured €118 million in a series B finance round to fund their development of AAVs with refined capabilities, able to carry longer genes.

The rapid rise of AI in biomedical research is also transforming how scientists design and test new therapies, including in gene editing. Stanford Medicine researchers have introduced CRISPR-GPT, an AI “copilot” that draws on extensive scientific literature and lab records to propose experimental designs, predict off-target risks, and justify its recommendations.

The patent wars

There are currently over 14,000 patent families related to gene therapy worldwide. Early patents mainly targeted basic delivery mechanisms and methodological approaches, but the focus has grown more specific over time, covering specific disease indications, vector designs and genetic modification techniques.

CRISPR-Cas9 in particular has been the topic of a major dispute over the last decade and the contest for the foundational patent rights is still ongoing. CRISPR-Cas9 was introduced as a programmable gene-editing tool in 2012 by Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, a discovery that later earned them the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Around the same time, Feng Zhang and the Broad Institute demonstrated its use in mammalian cells, triggering a long-running patent battle. This leads to uncertainty and legal risks which impede those who wish to use CRISPR.

CVC

In Europe, one of the two leading CRISPR patent portfolios is held by the team behind the Nobel-winning discovery, collectively known as “CVC” (the University of California, the University of Vienna and Emmanuelle Charpentier). Their core rights are based on the fundamental patent family originating from parent application EP2800811, along with a series of divisional filings. The patents EP2800811 and EP3401400 (one of the divisional applications in the family) were originally maintained by the EPO Opposition Division, but these decisions were appealed. In its preliminary opinions, the Board of Appeal found that neither patent could rely on the earliest priority date because the earliest priority document failed to disclose the essential PAM sequence required by the CRISPR-Cas9 technology, rendering the claims not novel over the Science publication from the same inventors.

CVC decided to withdraw their approval of the granted texts in 2024, effectively revoking both patents to possibly avoid an adverse final decision that could negatively affect their broader CRISPR portfolio (see our relevant article here). The patent family still includes other active members including EP3597749, EP4289948 and EP4570908, with EP3597749 and EP4289948 already facing opposition. We can expect further disputes as the CRISPR patent landscape continues to evolve.

The Broad Institute

On the other hand, the Broad Institute (together with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard College as co-applicants) also obtained early patent rights in Europe based on the patent family originating from parent application EP2771468. The patent was revoked in 2020 on the basis of intervening art that only became citeable due to invalid priority (in which one of the opponents was represented by Mathys & Squire). In this regard, the Board of Appeal held that a priority claim was deemed invalid if a proprietor was unable to show, when challenged, that the applicants for the subsequent application included all of the applicants for the priority application or their successor(s) in title at the time the subsequent application was filed (see our earlier articles here and here).

Interestingly, the recent decision G1/22 issued by the Enlarged Board of Appeal has significantly relaxed the EPO’s approach to “same applicant” priority. The EBA decided that there is a “rebuttable presumption” that the priority applicants approve of the subsequent applicants’ entitlement to priority, regardless of any difference in names (see our earlier article here). The divisional patents EP2784162 and EP2896697, and the relevant patent EP2764103 were originally revoked by the Opposition Division under similar reasons as with EP2771468, but the Board of Appeal have decided to return these cases back to the Opposition Division as the priority entitlement is now considered valid. Opposition proceedings are ongoing, and it will be interesting to see how these cases ultimately unfold.

Recent developments

Other companies have also been entering the legal battlefield in recent years. ToolGen, for example, filed an infringement suit against Vertex’s CASGEVY® therapy in April 2025 in the UK. The ongoing wave of disputes illustrates that the CRISPR and gene therapy patent landscape remains highly competitive. Thus, securing robust patent protection is crucial for companies seeking to commercialise their technologies.

How to protect innovation in gene therapy

Protecting gene therapy technology in Europe requires an early, well-structured patent strategy.

The foundation of any successful patent strategy is a comprehensive freedom-to-operate (FTO) analysis, which should be conducted as early as reasonably possible in the development pipeline. FTO searching allows innovators to identify third-party patents that may block research or manufacture of a gene therapy product. This is especially important in fields such as CRISPR-Cas systems, where multiple parties hold overlapping rights. An FTO review not only helps avoid infringement but can also inform strategic design-arounds, licensing decisions, and the scope of future patent filings.

Equally critical is the issue of valid priority filing, an area that has been at the centre of some of the most high-profile European disputes in gene editing as discussed above. The EPO is well known to be very strict on added matter, and it extends to the assessment of priority validity. The priority filing should include all essential features of the invention and the way for performing the invention that are later claimed. Omissions can result in the loss of the earliest filing date and, consequently, exposure to intervening prior art. Although the recent decision G 1/22 appears to have relaxed the “same applicant” priority rule in Europe, the underlying requirement of adequate technical disclosure remains stringent and fundamental.

Patent drafting

When drafting the patent application itself, a successful strategy typically involves pursuing multiple categories of claims. For gene therapy inventions, this may include:

- Composition of matter claims for the drug product, which might include specific nucleic acid, Cas enzymes, engineered cells, viral vectors, lipid nanoparticles or other delivery vehicles

- Sequence-specific claims for novel nucleic acid sequences

- Medical use claims for using the gene therapy product as a medicament or to treat specific diseases.

- Formulation claims for the specific solutions, buffers or excipients used to stabilise and deliver gene therapy components

- Dosage regimen and administration-route claims for optimised therapeutic windows and dosing approaches

- Manufacturing and process claims for nucleic acid production, cell-expansion protocols, vector-production methods, or purification steps involved in the production of the gene therapy product.

In view of the complexity of gene therapy patents, it is important to seek professional support. The application must be drafted effectively to secure appropriate breadth of protection, while also facilitating a smoother path to grant.

SPCs

Finally, as products approach regulatory approval, innovators might also consider Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs). SPCs extend protection for medicinal products beyond the standard 20-year patent term. This compensates for the time lost during regulatory review. Gene therapy products authorised in the EU may be eligible for SPC protection, provided they meet the regulatory and patent linkage criteria. Our professional team can guide applicants through SPC strategy and the application process (see here for further information).

Gene therapy is advancing rapidly, but its patent landscape remains complex and highly competitive. Careful strategy including strong priority filings, thoughtful claim drafting and early FTO analysis is essential. Robust IP protection allows innovators to focus on advancing therapies rather than defending their inventions.

On the 13th of November, author Ruth Leigh came to our London office in the Shard to join us for this month’s book club and give a talk about her career journey.

Ruth previously worked at Mathys & Squire as one of our support staff and we are pleased to see the success she has achieved following her time here. She has published seven books, including her main book series revolving around the life of the main character, Isabella M. Smugge, an influencer who has just moved to the countryside from London.

We had the opportunity to speak to Ruth about her journey as an author, as well as to look back at her experience at the company twenty-five years ago. In the interview, she looks at how the firm has evolved, highlighting the importance of diversity and inclusion, and shares how her rewarding her time at Mathys & Squire was, putting her in good stead for the rest of her career.

To start things off, can you give us a brief introduction?

These days I’m a full-time writer, but I only started that career full-time in 2022, so it’s still quite new. But I’ve been a freelance writer since 2008. I’ve had an interesting range of careers, looking back. I like to challenge myself, so I’ve done lots of different things.

I’ve been writing fiction since 2021. So far, I’ve written four funny, contemporary books about a TikTok and Instagram influencer, and I’m writing the fifth in the series. I’ve also written a collection of short stories around minor characters in Pride and Prejudice, a poetry book and my latest, a selection of my blogs from 2019-2023.

How long did you work at Mathys & Squire and what did you do?

I came to Mathys & Squire in 1998. Before that, I was working for the Head of Department of Psychology at UCL and it felt like it was time to take a leap. I went to an agency and the job supporting Paul was the first one that came up. I’d never worked in the private sector, and I didn’t know anything about law, but I was used to being in a supportive PA role to quite important people, so it seemed like an obvious progression.

Back then, we were all in one quite small office. I was doing admin work for Paul, but very quickly we started doing other stuff as well. Recruitment was very low key at that time, and rather one-note, so with his encouragement, I added the job of recruitment for Mathys & Squire to my list. I’m delighted to see that some of the staff I helped to recruit are still with the firm. One of our biggest clients was involved in a huge court case while I was there too, so a lot of my time was spent helping with that.

In terms of recruitment, I was very keen to make it more diverse. We were already seen as one of the more go-ahead patent firms, but more diversity was needed. Throughout my time there, I learnt a lot and met some great people, and it was hard work, but I am proud of the fact that by the time I left it looked very different from when I arrived.

In 2003, I was expecting my first child and became a consultant recruiter, working from home. That wasn’t a thing in 2003, so I was breaking new ground there as well.

What was your favourite part about working at Mathys & Squire?

I would say the social life. Our team ended up as quite a big group, so when we managed to get out and about (usually on a Friday evening), we used to have such a good time and I’m still in touch with some of them now, which is lovely.

I do love a challenge and, at Mathys & Squire, every day there was a new one and it really helped me grow positively as a person.

What motivated you to change to a career in writing?

It’s what I’ve always wanted. Apparently, when I was a little child, if anyone said to me, “What are you going to be when you grow up, Ruth?” I would always say, “I’m going to be a writer.” And I think it’s interesting how I worded it. I didn’t say, “I quite fancy being a writer,” or “I might be a writer;” I always said, “I’m going to be a writer.”

And I read all the time. I mean literally all the time. I’d read 15 to 20 books a week if work didn’t get in the way, that’s just my thing. It was the one subject I was naturally good at so it made sense to think that writing would be my career.

My early life wasn’t very happy. When I was 18, I ran away from home to Exeter and I thought, “Ruth, other people have dreams, but that’s not for you. Crush it underfoot and just get on with living your life, that will have to do for you.” So, I put the idea of being a writer to one side and though I would never come back to it again.

I’m glad I did things the way I did and that I didn’t plan it all out, because everything I have done has fed into my writing, including working at Mathys & Squire. I think in book five I’m going to make one of the couples my heroine knows patent attorneys. Why not?

How would you summarise the books you have written?

The main character is called Isabella M Smugge (her name spells out “I Am Smug.”). When I wrote the original blog about her, it was just for fun, creating this ludicrous woman inspired by people I’d seen on social media during lockdown. I’d see these women who were bragging about living their best lives and making banana bread and doing Joe Wicks every morning and I was so sick of it.

I created this character who lives in an incredibly privileged bubble: lots of money, perfect husband, perfect children, perfect house, babbling on Instagram and TikTok about her wonderful life. But I knew that couldn’t be the whole story. So, when I sat down to write the first book, I thought, right, she’s going to have to move out of London to a little village in Suffolk.

She’s narrating it, but she’s an unreliable narrator. She’s telling you how perfect her life is and how everyone loves her, but that’s not the case, and you start to see it through somebody else’s eyes and the cracks start to show. She changes throughout the books, but not too much, because I’m not a fan of books where someone starts off absolutely horrible and by the end, they’re everyone’s best friend. That’s not how it works. Isabella is a lot nicer, but she is still a snob by the time we get to book four.

What is the worst and best part of being a writer?

The worst part is the self-doubt – when you sit there and look at a blank screen and think, “Ruth, you’re a complete fraud. What makes you think anyone’s going to like your stuff?” You spend so much time by yourself, sitting with your own company, and those voices come in and that is hard.

The best bit is when you meet someone or you get an e-mail from a reader telling you that they loved your book and that it touched them. It really matters to me that I can make someone’s life better. People often write to me to say that they’re in a bad place, but that my books are really helping them.

Do you think there are any similarities between your work when you were at Mathys & Squire and your work now?

I’ve never thought about that before, that’s a great question. I think that I often do difficult things in my job now – things that I thought I never could, such as going into a classroom full of 15-year-olds to deliver an inspirational workshop. I can see them thinking, “Great, another boring middle-aged woman banging on about something we hate.” But within five minutes I’ve cracked them. It’s going in and doing something that no one thinks you can do, and that’s what it was like at Mathys & Squire. Within my team, we were doing things we’d never done before, and we were looking at things which seemed unachievable or stupid to even try and trying anyway.

Did you bring anything you learnt whilst working at Mathys & Squire into your career as a writer?

I think it taught me perseverance. I already thought outside of the box, but it increased that quality.

Finally, we can’t end this without touching on the intellectual property side of things. As a writer, copyright protection plays a significant role in what you do. Did you find that you had more knowledge going into it about copyright after working here?

That’s a very interesting question. Yes, it did help me. When I wrote the novels, I was really careful.

With my Issy Smugge book, I work closely with my publisher, who has a set of house rules. When I co-founded a small press and published the other three books through them, no one was telling me what I could write. I had to really think about that, particularly with the Jane Austen book, because I had to know about the law on intellectual property, copyright and public domain. If an author has been dead for seventy years, you can use their words, but there’s something called fair use, so you can’t just quote an entire chapter, because that’s not fair.

Quite often when I’m working with other authors, they’ll ask me questions like that and I’ll find myself talking about IP, and they say, “Wow, how do you know about that?”

I was driving my teenager daughter to college the other day and she was asking what I used to do, so I started describing Mathys & Squire. And I told her about our slightly eccentric client who used to come in every two years with crazy inventions. She was slightly in disbelief that that’s what I used to do. “You did science stuff, Mum? You?” She had a point. I don’t really do science.

I once heard someone say that the patents and trade mark world is like a secret profession. If you say you work in a law firm, everyone knows what you mean. But the minute you mention patents and trade marks, people have no idea what you’re talking about. It’s niche. So, knowing what I knew about trade marks and copyright and inventive step has actually really helped because I’ve not fallen into the pitfalls that other authors sometimes do.

What advice would you give to an artist, whether they’re producing physical art, books or music, on protecting their creation?

You have to check that you’re not infringing copyright. One of the things that’s key in our industry is that you cannot legally quote song lyrics in your books. I got round that, but I did cause my agent some alarm, because I made up a band which appeared in my third book. The editor said, “ Ruth, you can’t do that,” but I explained that it was fine as I invented the band and their back catalogue (one of their songs will be trending on TikTok in book five).

We would like to thank Ruth for taking the time to come back to Mathys & Squire. Mathys & Squire would not function without our support staff, from the people here now to those that have gone but left their mark, and Ruth is just one example of the talent and individuality which we are proud to embrace here.

We are delighted to be the Forum Partner for ELRIG’s UK Forum “Outside the norm”, an event at the University of Warwick, Coventry, exploring engineering biology for drug discovery.

Partner Martin MacLean and Managing Associate Lionel Newton will be representing the firm at ELRIG’s UK Forum “Outside the norm”, taking place on the 13th of November.

Lionel Newton will be delivering a talk that explores how strategic intellectual property (IP) management underpins success in the advanced therapeutics sector. From early-stage spin-outs to clinical development and eventual acquisition, ventures that proactively build and evolve their patent portfolios are best positioned to attract investment, secure partnerships, and sustain competitive advantage. Drawing on real-world experience, including a brief case study, the session highlights how a well-planned IP strategy not only protects innovation but also drives commercial value throughout the therapeutic development.

About ELRIG

ELRIG is a not-for-profit organisation that brings together the global life science and drug discovery community through free-to-attend events. With a network of over 12,000 professionals, it is dedicated to promoting inclusion and accessibility whilst encouraging innovation across the sector. This event will highlight the use of synthetic biology and engineered biological systems in accelerating drug development, discovering new classes of medicines and unlocking previously undruggable targets.

Please reach out to our team if you are interested in arranging a meeting.

For more information on the event, visit the website here.

IPSS Electra Valentine has co-written an article in response to Black History Month, discussing the notion of ‘professionalism’ at work and how we must separate it from Eurocentric standards.

The article examines the discrimination against Black professionals ingrained in what we deem acceptable and ‘smart’ in the workplace, such as attitudes towards natural Black hair, emphasising the importance of allowing and embracing authentic presentation. It highlights that any rules regarding appearance for client contact or formal settings should be limited to reasons of safety, hygiene or product integrity, not style or taste.

The article also features a quote from IP Support Manager at Mathys & Squire, Christine Youpa-Rowe, outlining our firm’s commitment to the Halo Code. The Halo Code is a statement on Mathys & Squire’s stance against discrimination towards Afro hair and an acknowledgement of our staff’s right to embrace all Afro-hairstyles.

You can read the full article here.

Partner Claire Breheny has been featured in ‘New non-alcoholic cocktail brands rise by 19% in two years’ by The Morning Advertiser, ‘Sober curious: How no and low alcohol drinks are redrawing legal lines’ by FoodBev Media and ‘Non-alcoholic cocktails trademarks surge 19% in two years’ by MCA.

In the articles, Claire provides commentary on the growing consumer interest in non-alcoholic beverages which is driving innovation and investment in the industry, as well as shaping trade mark filing activity.

Read the extended press release below.

The number of new alcohol-free cocktail brands being launched in the UK continues to rise with UK trade mark filings for non-alcoholic cocktails jumping 19% in two years to 515 from 433, according to Mathys & Squire, the intellectual property (IP) law firm.

This growth reflects how companies are prioritising alcohol-free product development to meet strong demand from Generation Z consumers seeking healthier, socially-inclusive drinking options.

During the same period, the number of new gin trade marks filed fell 9% from 642 to 582, while rum filings decreased 5% from 662 to 627, demonstrating changing consumer preferences toward alcohol-free alternatives.

However, whisky trademarks moved in the opposite direction, growing 7% from 714 to 761. New trademarks are being filed in order to market more budget whisky brands, with shorter ageing periods, without jeopardising existing upmarket brands.

The surge in non-alcoholic cocktail filings reflects a broader growth in innovation and investment across the broader alcohol-free drinks segment.

Leading companies, including Diageo, are investing significantly in new product launches, alongside marketing campaigns and sponsorships, to capture growth in the expanding alcohol-free market.

Claire Breheny, Head of Trade Marks at Mathys & Squire, says:

“The increase in non-alcoholic cocktail trademarks shows how alcohol free alternatives are being developed for all the main drinks categories.”

“Health trends and Generation Z drinking habits are transforming industry innovation priorities and investment strategies.

“Businesses that fail to innovate effectively risk losing out on one of the fastest-growing and most dynamic market segments in the global drinks industry.”

Is it cute or is it terrifying? No toy has ever caused such a divide in opinion. However, no matter what people think, the impact is the same: everyone has been talking about this mischievous-looking creature. The Labubu was officially the viral sensation of 2025.

Where did Labubu come from – and what now?

The origin of Labubu can be traced back to the mind of artist Kasing Lung, born in China and raised in The Netherlands. His illustrated book trilogy “The Monsters”, published in 2015, unveiled a whimsical world, shaped by his Chinese heritage and fascination with Nordic folklore, and brought various eccentric characters to life, including Labubu.

In 2019, Kasing Lung signed an exclusive licensing agreement with Pop Mart, giving the company commercial operation rights and the ability to transform Labubu from a toy to a powerful IP asset.

However, it was not until 7 years later, at the end of 2024, when the peculiar pet really started jumping into people’s shopping bags. Their scarcity is part of their appeal, with people going to great lengths to track them down, queuing for hours and paying hundreds of pounds for the addictive “blind box” experience. Social media is flooded with people flaunting their Labubus and special-edition Labubus are being sold at auctions for over $100,000.

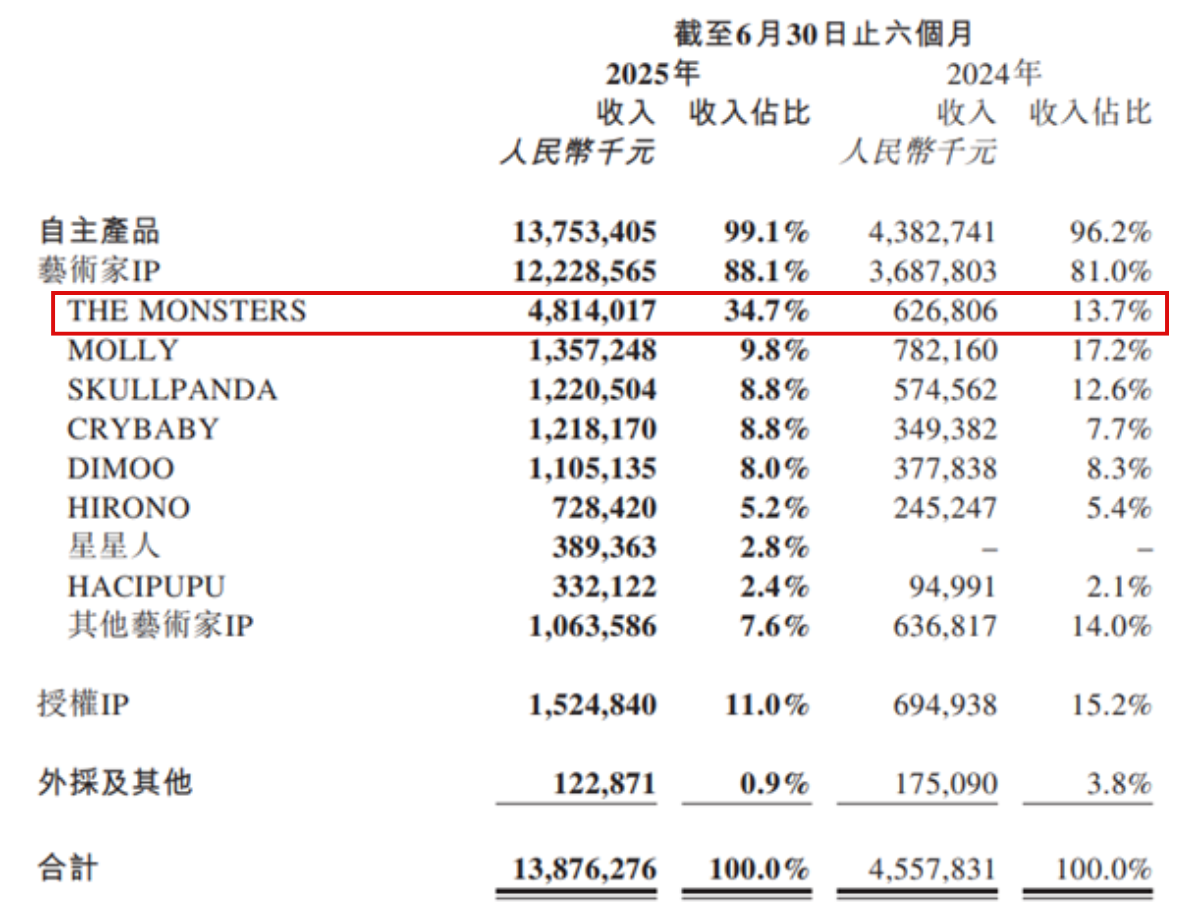

According to Pop Mart’s 2025 Interim Results Announcement, “The Monsters” generated an impressive 4.81 billion yuan (approximately $669.88 million) by 30 June 2025, making it Pop Mart’s most profitable IP.

Pop Mart’s IP strategy

In the toy industry, when products transcend their physical counterparts, becoming distinctive, memorable brands, IP plays a vital role. It allows a story or symbol to become a concrete entity which the owner can safeguard and profit from. With the IP safely in their pocket, Pop Mart was able to spread the Labubu figurines over the globe and watch the money flow in.

Pop Mart displays a robust, multi-layered approach to their IP, encompassing copyright, trade marks, and patents, demonstrating an understanding that design and branding are both highly valuable assets. By 2024, the company held over 1,200 trade marks, 1,600 copyrights and 45 patents.

Pop Mart’s patents mainly cover innovations in product functionality and production techniques, including toy assembly methods, and CNC water transfer printing and related equipment. Design patents, on the other hand, primarily protect the toy’s overall shape, facial expressions, and distinctive visual features such as unique clothing or accessory designs.

After securing its core IP, Pop Mart began taking strong measures against infringers and imitators.

Labubu’s evil twin

It may have seemed like Pop Mart could walk blissfully off into the sunset after hitting the hype sweet spot, but where there is hype, counterfeiters soon follow. The toy industry is a significant victim of the counterfeit market, which in 2022 was valued by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) at $464 billion. Whilst the internet allows a product to gain worldwide popularity, carving a path across the globe also makes it easier for fake versions to appear.

In Labubu land, “Lafufu” has become the widespread term used to refer to the counterfeit toys. “Lafufus” have become almost as sought-after as Labubus for various reasons, including their lower price tag, extra, unique features, or even just a wish to go against the mainstream. They have become so popular that Lafufu manufacturers, small factories which are mainly located in the Guangdong and Hebei provinces in China, are also struggling to meet demand. They may seem like silly, affordable toys but do they represent something more sinister?

Counterfeit goods are a threat to brand value and can seriously harm revenue streams. They can even be health risks to consumers, especially when it comes to children’s toys, as they are often poorly made. Not only are they a threat to Pop Mart and their customers, Chinese authorities are also concerned by what the mass of “Lafufus” means for China’s growing reputation as an IP powerhouse. Labubus are an example of China transforming creativity into business opportunity, rivalling other Asian countries with a significant global cultural influence, such as Japan and South Korea, whilst Lafufus undermine the country’s innovation and prevent fair competition.

Nevertheless, Pop Mart is not giving up. They continue to strengthen their efforts in maintaining their unique position in the market, demonstrating the importance of strong IP protection.

Brand enforcement

A key aspect of enforcing the protected status of a brand is carefully monitoring the market so that you are aware if counterfeit goods appear. Pop Mart has implemented identifiers on their products to make genuine Labubus distinguishable from frauds, such as scannable QR codes, serial numbers and unique packaging design.

Once counterfeit goods are identified, it is important to take rapid action to minimise damage to the brand. Pop Mart’s 2024 Annual Report notes that it “identified more than 10 forged authorisation letters, took down the domain names of 5 overseas websites selling infringing products, initiated 3 infringement lawsuits, and successfully intercepted over 1.3 million infringing products at customs, making every effort to safeguard the Company’s intellectual property.”

In 2019, Pop Mart filed an invalidation request with the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) to challenge the unauthorised registration of the Labubu design patent. The CNIPA panel declared the entire design patent for the Labubu figure (No. ZL201830002145.4), which had been filed and granted to another party in 2018, invalid. The ruling reaffirmed the company’s originality and legitimate ownership of the character’s IP rights.

IP collaboration

Although the internet frenzy may be tailing off, Pop Mart continues to maximise the potential of its IP by forming strategic partnerships with other brands. For example, on the 18th of September, UNIQLO launched a clothing line featuring the “The Monsters” illustrations. This involves drawing up a licensing agreement so that Pop Mart are remunerated for the third-party use of the Labubu brand, as well as to ensure that the use aligns with Pop Mart’s wishes and there is no misuse of their image.

Holding the copyright to his creation, Kasing Lung profits from licensing deals and has now taken Labubu a step further, partnering with luxury Parisian leather brand MOYNAT to release a collection of Labubu-adorned handbags and leather accessories, which became available on the 11th of October.

Conclusion

Some people may think that Labubus have sent the world crazy, but, although their cuteness remains subjective, there is no doubt that they are an insightful case study on business strategy in a digital world, including the necessity of building and maintaining a robust IP portfolio. When the internet means that an individual’s or business’s creation could go viral overnight, a rigorous strategy for protecting IP, as well as surveillance of third-party use, is crucial.

Pop Mart’s success is no coincidence. Its strong IP framework sets a model for the designer toy industry, ensuring early copyright registration, strategic trademark protection and design rights for distinctive products. A vigilant infringement monitoring system allows the company to respond swiftly to counterfeits through legal and administrative action, safeguarding both brand value and market integrity.

An interview with Partner Claire Breheny was recently featured in ‘Growing interest in non-alcoholic beverages opens new opportunities for brands’ by World Trademark Review. Claire provided commentary on how businesses looking to meet the heightened demand for non-alcoholic and low alcohol alternatives must ensure that their intellectual property strategy aligns with their new goals.

The article explores how shifting to non-alcoholic products is likely to have a positive impact for businesses. Firstly, a more extensive product line means a greater number of potential customers and, secondly, product advertising will be less bound by laws on alcohol advertising, making the brand more appealing to licensees. Claire highlights the fact that the market is still evolving and, despite large brands already offering non-alcoholic beverages, there is space for emerging brands to thrive if they position themselves in the right way.

To read the full article click here.

We are honoured to share that Mathys & Squire is a Silver sponsor of the WIPR Trademark and Brand Protection Summit 2025, taking place from the 28th to the 29th of October in San Francisco. Partner Claire Breheny will be attending the event in person.

The World Intellectual Property Review is the principal online publication for professionals in the IP industry, publishing news and guidance on the current issues facing businesses and legal practitioners.

WIPR organises the Trademark and Brand Protection Summit to connect prominent trade mark experts, including both the largest and most innovative brands and leading outside counsel. The event provides a pivotal opportunity to engage with like-minded peers and discover valuable insights into trade mark prosecution and enforcement in light of recent disruption for brand owners, such as AI and domain-related issues.

The program offers expert-led sessions and interactive panels designed to share a wide range of expertise in the latest legislative developments, strategic approaches to safeguarding your brand and how to maintain a competitive edge in an ever-changing global marketplace. On the 28th of October, Head of Trademarks Claire Breheny will be moderating a panel discussion on “Overcoming the Growing Problem of Domain Squatting and Trademark Misuses Online.” Alongside the other speakers, she will be sharing her in-depth knowledge on using innovative tools to detect infringers, and how to combat infringement cost-effectively and quickly.

For more information on the event, visit the website here.

Contact our team

Claire Breheny – Partner | [email protected]

Partners Martin MacLean and Anna Gregson have been featured in ‘Global vaccine patents rise, as data reveals shift in Big Pharma strategy’ in LSIPR, ‘Global vaccine patents up 7% in a year despite US government’s stance’ in Manufacturing Chemist and ‘Vaccine patent applications hit record high, new data reveals’ in Drug Discovery World.

In the articles, Martin and Anna provide commentary on how, despite anti-vaccine rhetoric stemming from parts of the new US administration, the number of vaccine patent applications being filed are still rising steadily after the post-COVID spike, highlighting that traditional vaccine technologies are making way for safer methods following the success of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine.

Read the extended press release below.

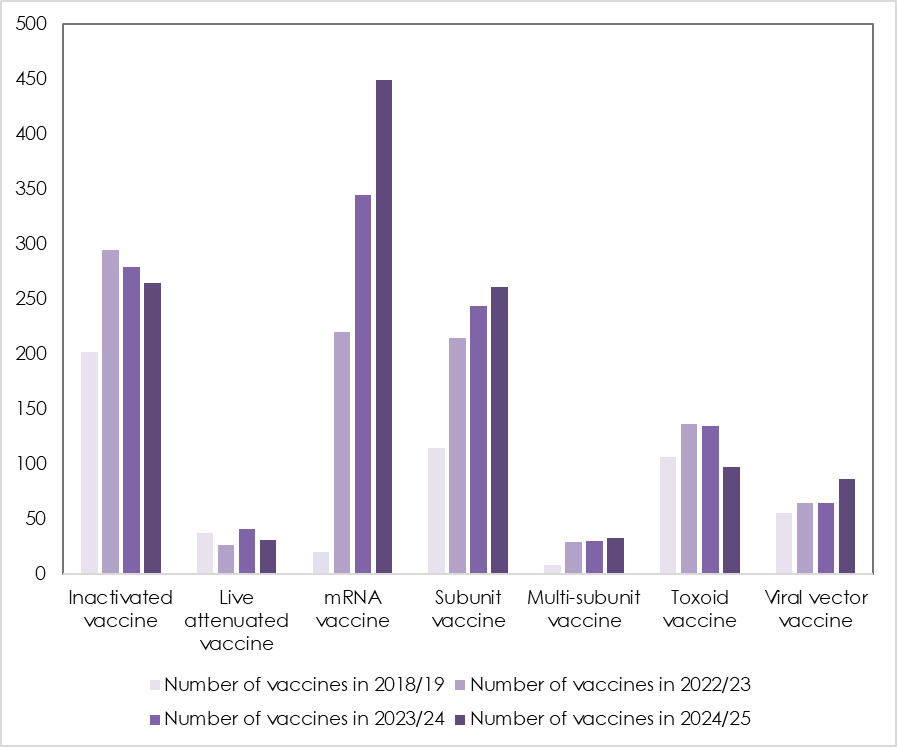

Global vaccine patents applications grew by 7% in the year to June 2025, rising to 1220 from 1135 the previous year, says intellectual property (IP) law firm Mathys & Squire.

Vaccine patent applications increased sharply after the COVID pandemic with 15% growth recorded in 2023/24, when patents applications increased from 983 to 1,135. Even so, the volume of applications is still up 129% compared with 2018/19, when there were just 542.

What is interesting to note is the very clear shift in vaccine strategy that has been adopted by pharmaceutical companies, and in such a short period of time. Traditional vaccine technologies such as toxoid vaccines and attenuated vaccines are being replaced by safer, more agile technologies such as mRNA vaccines.

Patent applications for RNA vaccines now dominate the evolving patent thicket, increasing 31% to 449 in 2024/25, up from 344 the previous year and only 20 in the year 2018/19. RNA vaccines deliver a small immune triggering part of the virus directly into a cell.

Mathys & Squire says vaccine technology is moving away from traditional vaccines to more advanced technologies like DNA and RNA vaccines. Traditional vaccines include ‘toxoid’ vaccine types, which use inactive toxins to prompt an immune response, like the tetanus vaccine, and subunit vaccines use proteins to trigger an immune response.

Consistent with this shift to new technologies, toxoid vaccines saw the sharpest drop in patent applications, with filings down 28% to 97 in 2024/25, from 134 the previous year. Inactivated vaccines saw a 5% drop to 264, from 279 in 2023/24.

Mathys & Squire says the success of the Covid mRNA vaccine shows that using these newer, more agile technologies can deliver effective protection at a lower cost than conventional vaccines. There are also significant safety benefits to the newer technologies.

Traditional vaccines, such as live attenuated vaccines or toxoid vaccines often require the culture of large quantities of the microbes. This requires expensive equipment and reagents and can be associated with safety and containment concerns.

On the other hand, the genetic material used in RNA vaccines is comparatively cheap and easy to produce. Additionally, since RNA vaccines do not contain a pathogen (either active or inactive) they are not infectious, making them safer for patients, clinicians and those involved in their manufacture, says Martin MacLean, Partner at Mathys & Squire.

Anti-vaccine comments from parts of the new US administration may further slow development of vaccines.

Mathys & Squire warns that recent anti-vaccine comments from some US Government officials risks adding to a slowdown in vaccine R&D.

Martin MacLean says: “Vaccine development is an expensive process. Mixed messaging from the Government could deter new investment – and therefore limit the number of new vaccines that can be developed and patented.”

RNA patents boom, and are now the largest number of new patent filings.

* Year end 30 June 2024. Figures are based on international vaccine patent applications published under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) during the 12 months to June 2019, 2023, 2024 and 2025, classified by type: inactivated (264), live attenuated (31), mRNA (449), subunit (261), multi-subunit (32), toxoid (97), viral vector (86).

Managing Associate Richard Jaszek has been featured in WIPR (World Intellectual Property Review) with his article, ‘Is the UK’s £16bn space industry being held back by out-of-date patent law?’

The article highlights how the rapidly advancing innovation in the space sector requires a robust intellectual property framework, the existence of which is ambiguous on account of the territoriality of patent law. According to Richard Jaszek, the UK is at risk of falling behind within the space-tech industry and it’s time to consider whether the nature of our patent law plays a part.

Read the article in full here.