The EPO’s Technical Board of Appeal 3.3.01 in recent decision T421/14 (and related decision T799/16) has provided guidance on when the requirements of sufficiency are met for claims directed to a second (or further) medical use of a known product – in particular where the therapeutic effect is only achieved in a subpopulation of responders and not the patient population as a whole. The decision confirmed that the existence of a group of non-responders does not result in a lack of sufficiency for claims directed to a general population and that the group of non-responders does not need to be excluded.

Established EPO case law for second medical use claims states that the attainment of the claimed therapeutic effect is a functional technical feature of such claims. To meet the requirements of sufficiency, the therapeutic efficacy of the composition and dosage regimen for the claimed indication must be credible. EPO case law has also established that the presence of a non-working embodiment is acceptable, as long as the specification contains information on the criteria needed to identify the working embodiments. Against this background, decision T421/14 considers the issue of sufficiency in a situation where the claim is directed to a general population of patients but encompasses a large group of non-responders.

The claims in question related to a dosage regime comprising aminopyridine for increasing walking speed in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients. MS, like many other diseases, shows a wide variability in pathology which results in only a proportion of patients responding to treatments. The application as filed acknowledged that it was known that only a proportion of patients, estimated to be about one third, responded to treatment with aminopyridine.

The opponent argued that the data within the patent did not demonstrate a therapeutic effect across the full scope of the claims due to the large proportion of the patient population treated being ‘non-responders’. Since the claims did not specify a step of initially identifying a patient as either a responder or non-responder, the opponent argued that the claim scope was incommensurately broad because it encompassed the treatment of patients not responding to the claimed treatment.

The Board of Appeal did not agree with the opponent’s position and stated that “the existence of non-responders is not a reason to deny sufficiency of disclosure” and that non-responders do not have to be excluded or disclaimed. The Board of Appeal also acknowledged that the existence of non-responders is “a common phenomenon which is observed with drugs in many treatment areas” and that it is common practice to treat patients with a drug and change their medication if they do not respond to treatment.

The Board of Appeal held that the criterion of sufficiency of disclosure is met if it can be shown that a relevant proportion of patients benefits from a treatment and that it has acceptable safety, since in these circumstances the skilled person in the art has the necessary technical information to perform the treatment. As the Board notes, the existence of non-responders is a common phenomenon, and innovators will therefore be reassured that in general this does not preclude a second medical use patent from being obtained. Questions remain regarding the requirement that a ‘relevant proportion’ of patients must benefit from the treatment, but it is interesting to note that the Board found that this requirement was met even when only a minority of patients were responders.

Today, 25 November 2020, the EU Commission published a new intellectual property action plan. The action plan, touted as “an intellectual property action plan to support the EU’s recovery and resilience” outlines possible future moves, noting that intangible assets are “the cornerstone of today’s economy”, with IPR-intensive industries generating 29.2% (63 million) of all jobs in the EU during the period 2014-2016, and contributing 45% of the total economic activity (GDP) in the EU worth €6 trillion.

The action plan also notes that the quality of patents granted in Europe is among the highest in the world, and that European innovators are frontrunners in green technologies, and leaders in specific digital technologies, such as connectivity technologies. That being said, the action plan notes that while smart intellectual property (IP) strategies can act as a catalyst for growth, European innovators and creators often fail to grasp the benefits of IP.

The action plan indicates that the Commission is willing to take stronger measures to protect European IP, to increase IP protection amongst European SMEs and to help European companies capitalise on their inventions and creations.

Ambitiously, the action plan also notes that the EU aspires “to be a norm-setter, not a norm-taker” and is keen to seek ambitious IP chapters with high standards of protection in the context of Free Trade Agreements, to help promote a global level playing field.

We summarise some of the key takeaways here.

Unified Patent (UP)

The implementation of the Unified Patent is seen as a priority in the action plan, indicating that it will reduce fragmentation and complexity, and will reduce costs for participants, as well as bridging “the gap between the cost of patent protection in Europe when compared with the US, Japan and other countries”. The action plan also indicates that it will “foster investment in R&D and facilitate the transfer of knowledge across the Single Market”.

SEP licensing

With the introduction of 5G and beyond, the number of standard essential patents (SEPs), as well as the number of SEP holders and implementers, is increasing (for instance, there are over 95,000 unique patents and patent applications supporting 5G). The action plan notes that many of the new players are not familiar with SEP licensing, but will need to enter into SEP arrangements, and that this is particularly challenging for smaller businesses.

One area that has garnered a lot of press attention recently relating to the licensing of SEPs, and in particular to businesses that are perhaps not as familiar with SEP licensing, is that of the automotive sector. The action plan acknowledges this and notes that “although currently the biggest disputes seem to occur in the automotive sector, they may extend further as SEP licensing is relevant also in the health, energy, smart manufacturing, digital and electronics ecosystems.”

To this end, the Commission is considering reforms to further “clarify and improve” the framework governing the declaration, licensing and enforcement of SEPs. This includes potentially creating an independent system of third-party essentiality checks, and follows off the back of a pilot study for essentiality assessments of Standards Essential Patents and a landscape study of potentially essential patents disclosed to ETSI also published alongside the action plan.

Modernising EU design protection

The Commission has indicated that it wants to “modernise” EU design protection “to better reflect the important role design-intensive industries play in the EU economy”. At present, the Commission is asking for stakeholder feedback on the options for future reform. Recent results of an EU evaluation show that the current legislation works well overall and is still broadly fit for purpose. However, the evaluation has also revealed a number of shortcomings, including the fact that design protection is not yet fully “adapted to the digital age” and lacks clarity and robustness in terms of eligible subject matter, scope of rights conferred and their limitations. The Commission also considers that it further involves partly outdated or overly complicated procedures, inappropriate fee levels and fee structure, lack of coherence of the procedural rules at Union and national level, and an incomplete single market for spare parts.

Updating the SPC system

While the Commission notes that, following an evaluation, the Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) framework finds that the EU SPC Regulations “appear to effectively support research on new active ingredient, and thus remain largely fit for purpose”, it believes the EU SPC regime could be strengthened to reduce red tape, improve legal certainty and reduce costs for business. One option being touted is to introduce a centralised (‘unified’) grant procedure, under which a single application would be subjected to a single examination that, if positive, would result in the granting of national SPCs for each of the Member States designated in the application. The creation of a unitary SPC, complementing the future unitary patent, is listed as another option.

Patent pooling in times of crisis

The EU Commission notes how the pandemic has highlighted the importance of effective IP rules and tools to boost innovation and secure fast deployment of critical innovations and technologies, both in Europe and across the globe, but that it sees a need to improve the tools in place to cope with crisis situations. To this end, the action plan includes proposals to introduce possible mechanisms for rapid voluntary IP pooling and better coordination if compulsory licensing is to be used.

Increasing access for SMEs to IP protection and the introduction of an “IP voucher”

The action plan notes that only 9% of EU SMEs have registered IP rights. It aims to help SMEs better manage their IP and improve their competitiveness by giving EU SMEs easier access to information and advice on IP. Through the EU’s public funding programmes and further rolled-out at a national level, EU SMEs will get financial aid to finance so-called IP scans (comprehensive, initial, strategic and professional advice on the added value of IP for the individual SME’s business), as well as certain costs related to IP filings.

This will happen through the implementation of an “IP voucher”, which is made available in co-operation with the EUIPO, providing co-funding of up to €1,500 for:

- IP Scans: up to 75% of the cost and/or

- registration of trade marks and design rights in the EU and its Member States: up to 50% of the application fees.

SMEs will be able to apply as of mid-January for the IP voucher, through a dedicated website. We understand that the voucher will be provided on a “first come first served” basis.

The action plan also indicates the EU Commission’s intention to make it easier for SMEs to leverage their IP when trying to get access to finance, and that this may be done for example through the use of IP valuations.

EU toolbox against counterfeiting

The EU commission notes that counterfeiting is still a major problem for European businesses and proposes that an “EU toolbox” is set up to set out a co-ordinated European approach on counterfeiting. The goal of this EU toolbox should be to specify principles for how rights holders, intermediaries and law enforcement authorities should act, co-operate and share data.

AI and blockchain technologies

The action plan notes that in the current digital revolution, there needs to be a reflection on how and what is to be protected – perhaps a nod to the recent litigation we have seen regarding whether an AI can be considered as an inventor. The action plan in particular notes that questions need to be answered as to whether, and what protection should be given to, products created with the help of AI technologies. A distinction is made between inventions and creations generated with the help of AI and the ones solely created by AI. The action plan notes that the EU Commission’s view is that AI systems should not be treated as authors or inventors, which is the approach taken by the EPO, but that harmonisation gaps and room for improvement remain and the EU Commission has indicated that it intends to engage in stakeholder discussions in this respect.

Conclusion

There is much to take in from the action plan, and we will closely monitor developments in all of the above areas to see what will be implemented and when.

This article was published in Global Banking & Finance Review in December 2020.

We are pleased to announce the appointment of Robin Richardson as associate to our trade mark practice, bringing the team headcount to a record high of 13 (made up of attorneys and paralegals), across our London, Birmingham and Manchester offices.

Robin is an attorney of the High Court of South Africa, a qualified trade mark attorney and soon to be UK qualified solicitor. He has several years of experience in trade mark, domain name and copyright protection, working with clients ranging from large multinationals through to newly formed startup companies. Robin has filed and prosecuted trade mark applications in the UK, EU, Africa and worldwide. He is an accredited domain name adjudicator with the South African Institute of Intellectual Property Law and settled a number of disputes before moving to the UK in 2018.

Robin obtained a B.SocSci and L.LB (Law) from the University of Cape Town and a Masters of Law, specialising in Intellectual Property Law from Queen’s University in Canada. Robin is a Fellow of the South African Institute of Intellectual Property Law and a South African-qualified trade mark practitioner.

After beginning his career with KISCH IP in South Africa where he worked for several years, Robin then joined Womble Bond Dickinson (UK) LLP, based in their Leeds office, in 2018.

Commenting on his appointment, partner and co-head of the Mathys & Squire trade mark team, Gary Johnston, said: “We are delighted to welcome Robin to the firm as our trade mark practice grows. His extensive trade mark skills and international experience will further augment the capabilities of our trade mark practice. Robin has a strong passion for solving domain name, trade mark, copyright and internet based legal issues which will add to our offering to clients. He will be a great asset to the firm.”

Robin Richardson added: “I am thrilled to have the opportunity to be working with the highly regarded team at Mathys & Squire. I share with them the same values and level of client service. I look forward to working with the firm, its innovative clients and contributing to the firm’s continued growth and development.”

This release has been published in World Trademark Review and Intellectual Property Magazine.

The EPO Board of Appeal has now issued its written decision in T 844/18 confirming the revocation of EP-B-2771468, an important CRISPR patent belonging to the Broad Institute, MIT and Harvard. The case was being widely followed due to the priority entitlement issues it raised. James Wilding and Alex Elder of Mathys & Squire represented one of the opponents.

The hearing was covered in our earlier news item here. To recap, the case turned on the issue of ‘same applicant’ priority. The PCT request for the application from which the patent derived had not included all of the applicants for the US provisional applications from which priority was claimed or their successors in title. The proprietors argued that this did not matter, because:

- the EPO does not have the power to assess legal entitlement to priority,

- in the case of joint applicants for a priority application, each can exercise the right of priority without the others, and

- the omitted PCT applicant was not, under US law, an applicant for the relevant invention in the US provisional applications or a successor in title thereto, because they had not contributed to that invention or derived rights from a contributing inventor.

At the hearing, the Board rejected all three arguments, consistent with established EPO case law and practice. With the written decision, we know the Board’s reasons:

In relation to the first argument, the Board concluded that the EPO’s power to assess ‘same applicant’ priority derives from the European Patent Convention (EPC): “Article 87(1) EPC clearly sets out a requirement that the EPO examines the ‘who’ issue of priority entitlement”. The Board rejected the proprietors’ analogy between the determination of entitlement disputes, which the EPO is not empowered to do, and the assessment of ‘same applicant’ priority, which the Board confirmed to be a formal assessment and not substantive.

In relation to the second argument, the Board firmly endorsed the current approach of the EPO, according to which all of the applicants named on a priority application, or their successors in title, must be named on the later European filing in order to introduce priority rights. Article 4A(1) of the Paris Convention and Article 87(1) EPC provide that ‘any person’ who has duly filed an application for a patent enjoys the right of priority, or their successor in title. The Board accepted that the ordinary meaning of ‘any person’ was ambiguous, but found support for the ‘all applicants’ interpretation in the authentic French text of the Paris Convention, in the object and purpose of the Paris Convention, and in the “many decades of EPO and national practice”. The Board further concluded that the bar to overturning the long-established case law and practice “should be very high because of the disruptive effects a change may have.” Those disruptive effects include the potential proliferation of priority-claiming applications and a significant shift in the prior art landscape.

In relation to the third argument, the Board held that it is the Paris Convention that determines who the ‘any person’ is who duly filed a priority application and who therefore holds priority rights. According to the Board, that person is simply “the person or persons who carried out the act of filing”, this requiring a formal assessment without regard to inventorship – consistent with earlier EPO case law. Accordingly, it was the unity of all of the applicants named on the US provisional applications who held priority rights, irrespective of inventive contribution.

In firmly rejecting the proprietors’ three arguments, the Board has maintained the status quo. Perhaps to underscore the point that ‘nothing has changed’, the decision has been coded for non-distribution to other Boards and it will not be published in the Official Journal of the EPO, notwithstanding the attention the case has drawn and the issuance of an EPO press communiqué (published today, 6 November) announcing the written decision. Whether the decision has a significant impact remains to be seen: the question of EPO power to assess legal entitlement to priority is pending in other appeals.

This article was published in The Patent Lawyer Magazine in November 2020.

As covered in our previous article (read the summary here), in September 2020 the LG München I (District Court of Munich I) decided in favour of Nokia in a preliminary injunction against Lenovo, in which the SEP case related to a video standard (H.264 – also known as MPEG-4 part 10), which Lenovo uses in its laptops and PCs.

Shortly after Lenovo appealed the decision against it having to remove the concerned products from its German website, the OLG Munich (Munich Higher Regional Court) made an unexpectedly quick decision on the appeal, and has now stopped the enforcement of the interim injunction. Lenovo’s products can now be ordered again on the company’s homepage.

In the present case (21 O 13026/19), the Court of Appeal has based its decision on the high probability that the patent in dispute lacks legal validity. In the German patent infringement system, the validity of the patent is not examined by the infringement court, but by the Federal Patent Court in a separate procedure (bifurcation). The infringement courts, however, have the possibility to suspend their proceedings if it is highly likely that the patent in dispute lacks legal validity. In the present case, the OLG has thus justified the revocation of the first instance ruling.

The decision of the OLG Munich suspends the preliminary injunction of the LG München, but on the basis of procedural grounds. It remains to be seen whether the Court of Appeal, in its written reasoning, makes further statements in the context of an orbiter dictum, which deals with the application of the FRAND criteria by the court of first instance.

Towards the end of September 2020, the LG München I (District Court of Munich I) decided in favour of Nokia on a preliminary injunction against Lenovo. The subject matter was an SEP case relating to a video standard (H.264 – also known as MPEG-4 part 10), which Lenovo uses in its laptops and PCs. After payment of the security deposit, which was set at €3.25 million by the LG München, Nokia has now enforced the decision and thereby stopped Lenovo from selling the respective products in Germany. The tech company has also had to remove the products concerned from its German website. Lenovo has already announced that it will not accept this decision and has appealed.

This infringement is only a minor issue in the present decision, while the focus is on the application of the FRAND criteria as established by the Court of Justice of the European Union (ECJ) in Huawei v ZTE. The Munich Court found that Lenovo’s efforts to reach a licence agreement were not sufficient within the meaning of the FRAND criteria. In the present case, the communication between the parties appears to have taken place in principle without significant delay, but without reaching an agreement on the monetary side of the FRAND conditions.

In doing so, the Munich Regional Court is following the guidance of the Federal Court of Justice in Sisvel v Haier (K ZR 36/17). Perhaps surprising is the low security deposit of approximately €3 million. This may be one reason why Nokia enforced the decision in order to increase the pressure on the licensee Lenovo, which, in the view of the Munich court, is unwilling to accept. The current decision is a further step towards Munich courts being SEP owner friendly. In particular, it further increases the requirements for SEP users and their willingness to negotiate. This positive development for SEP owners certainly leads to increased caution for SEP users in product development, but particularly in ongoing license negotiations. This could also be seen as judges strengthening the patent rights against the plans of the German government to change patent law.

In this article, which was published in Volume 12, Issue 13 of the International Pharmaceutical Industry (IPI) Journal, Mathys & Squire Partner Martin MacLean demonstrates how, following the case of Regeneron v Kymab, transgenic mice claims have been found insufficient by the Court of Appeal.

The Supreme Court judgment (24 June 2020) sends a clear “no” Brexit message to any big pharma contemplating corporate muscle-flexing of excessively broad patent claims. This ruling overturned the position held by the Court of Appeal that, for patents relating to “a principle of general application”, there was no requirement to teach how to make the full range of claimed products. In this regard, the Court of Appeal held that Regeneron’s contribution to the field extended beyond the products (transgenic mice) that could be made back in 2001, and instead related to the general principle of providing ‘better’ mice (thereby overcoming a prior art immuno-sickness problem inherent to mice transfected with human DNA). With hindsight, the Court of Appeal allowed too much weight to be given to the relative contribution the ‘better’ mice aspect provided in producing a(ny) mouse having commercial utility. In sum, the Supreme Court considered the Court of Appeal had incorrectly watered down the “sufficiency of disclosure” requirement of patent law and, in doing so, this judgment maintains a sensible balance between patent law enforceability and invalidity and provides guidance on what might constitute a ‘principle of general application’ for which broad claim scope might be held valid.

Click here to read the article in full. This provides an update to the original version, which was published in June 2020.

We are delighted to share the news of our client, Poseidon Plastics, has been awarded a £2.6 million grant from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), the national science and research funding agency, as part of its Smart Sustainable Plastic Packaging (SSPP) challenge.

The full press release is available below:

Using its proprietary technology as a platform, Poseidon’s mission is to develop a PET plastic recycling infrastructure on an industrial scale. This grant will be used to commercialise Poseidon’s scientifically proven chemical recycling technology through the construction of its first commercial facility, initially capable of processing 10kpta of waste PET. Construction is planned to start in Teesside in the second quarter of 2021 and will be completed in 2022.

The facility will redirect the equivalent of over one billion bottles per year out of landfills and the environment, to instead be repurposed into consumer packaging and other end-uses by Poseidon’s commercial partners. This facility marks the start of Poseidon’s programme to expand its chemical recycling process across the globe, rapidly expanding its output of recycled plastic feedstock, and reducing the use of PET as a ‘single-use’ plastic worldwide.

Partnering with waste collection experts Biffa Polymers, PET resin producers Alpek Polyester UK and DuPont Teijin Films UK, the University of York’s Green Chemistry Centre of Excellence and polyester fibre end-users, O’Neil’s and GRN Sportswear, Poseidon Plastics will demonstrate how previously unrecyclable post-consumer and post-industrial packaging and film, alongside other hard-to-recycle PET wastes can now be chemically recycled back to virgin-quality PET feedstock, Poseidon rBHETTM, for use in the manufacture of new consumer end-use goods.

By completing the supply chain from waste collection and sorting to feedstock production and PET manufacture through to consumer end-use goods, Poseidon and its partners will achieve a UK-first, a fully circular economy for PET plastic.

Around 80 million tonnes per annum of PET is produced globally, only a quarter of which is recycled. After the end of short first-use cycle, the majority of post-consumer and post-industrial PET plastic is currently incinerated or dumped in landfill, as it is deemed unsuitable as a feedstock for current recycling systems and processes. This is where Poseidon looks to make an immediate and significant difference; PET is lightweight, strong, inexpensive and with Poseidon’s proprietary technology, a valuable feedstock within a closed-loop circular economy.

Martin Atkins, CEO of Poseidon Plastics, commented: “We are delighted that the potential of our technology has been recognised by the government through UK Research and Innovation. This grant, as part of UKRI’s SSPP challenge, represents a significant and tangible commercial step on our way to achieving our ambitious, global-scale recycling targets.

“With the help of Alpek Polyester and our other partners, the new Teesside plant will evidence the scalability of our advanced recycling process and help us towards our core goal of making an immediate, significant, and sustainable impact on the global issue of plastic waste.”

Commenting on the news, Mathys & Squire partner Chris Hamer, who acts for Poseidon Plastics, said: “This is excellent news for Poseidon Plastics, as well as a positive step for green technology companies as the UKRI has invested a significant sum to tackle the important issue of plastic waste recycling. This would not have been possible without the specialist expertise and determination of the team at Poseidon Plastics – I look forward to seeing the construction project begin!”

On the last day of 2019, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) announced the latest amended guidelines for patent examination effective on 1 February 2020. This amendment was announced only three months after the previous amendment made in September 2019. This unusually speedy amendment to the guidelines reflects the Chinese government’s plans to strengthen the protection of IP rights in the fast-growing high-tech fields of artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain.

What’s new

A new section (Part II, Chapter Nine, Section Six, ‘the examination guidelines for inventions that contain algorithms or business rules and methods’) has been added to the guidelines. This new section aims to clarify the examination of inventions relating to AI, internet plus[1], big data and blockchain, which normally contain intellectual activities such as algorithms or business rules and methods.

The new guidelines indicate that the ‘as-a-whole’ principle for considering patentable subject matter (Article 25.1(2) and Article 2.2), as well as assessing novelty and inventive step – technical features and features relating to algorithms or business rules and methods – should not be separated in a claim. Whether a claim constitutes a technical solution should be assessed based on the technical means, the technical problem and the technical effect of the claim as a whole.

The ‘interaction-consideration’ principle for assessing inventive step is as follows: to be considered as contributing to the inventive step of a claim, features relating to algorithms or business rules and methods should be closely integrated with technical features (‘mutual supportive and interactive relations in function’) to form a technical means to solve a technical problem and result in a corresponding technical effect. Otherwise, those features relating to algorithms (in effect mathematical methods) and business rules or methods would be considered non-technical and therefore not relevant when assessing the inventive step of a claim, in a manner similar to that taken in Europe.

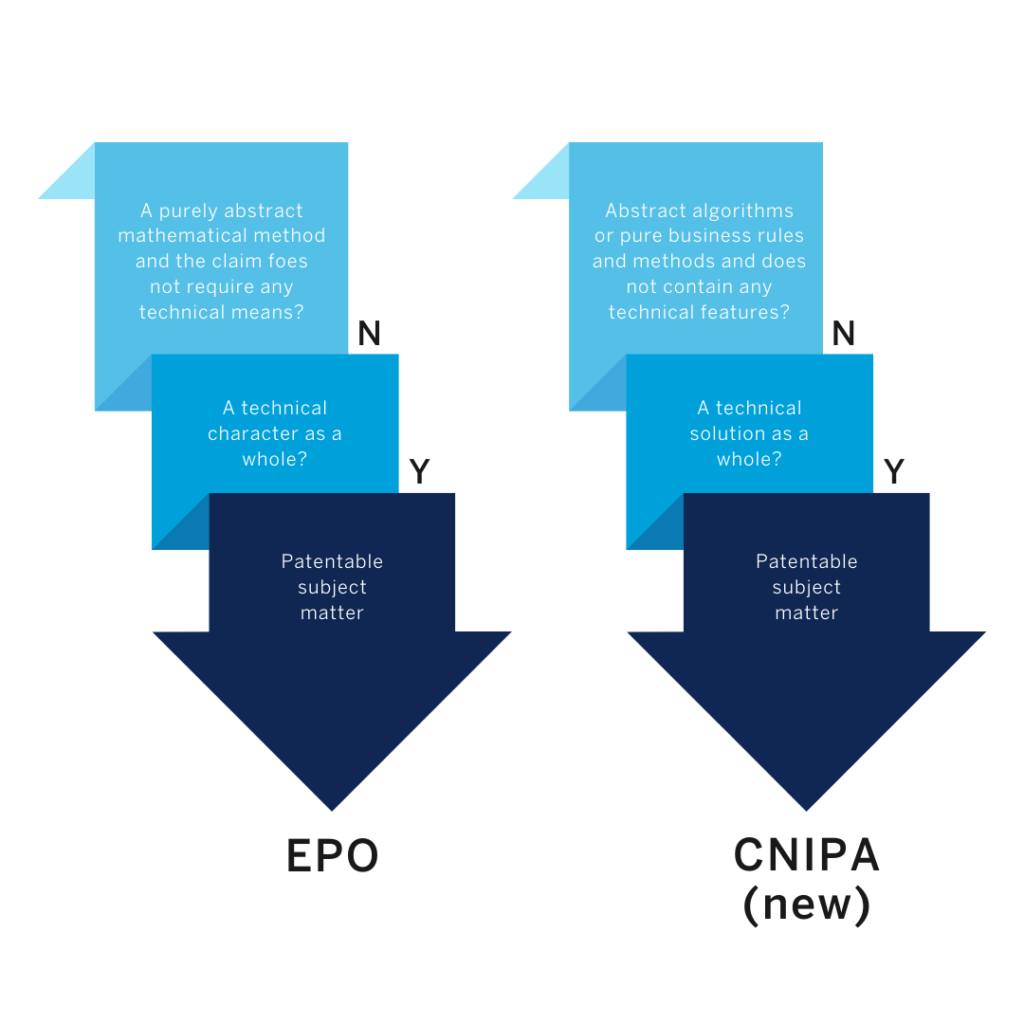

EPO and CNIPA new guidelines

Details about the new section of the Chinese guidelines can be found in Table 1 (emphasis added) with a brief comparison between the European Patent Office (EPO) and the CNIPA guidelines.

| EPO | CNIPA (Part II, Chapter 9, Section 6x) |

| Case Law of the Boards of Appeal of the EPO, I.A.2.2.2 “The exclusion applies if a claim is directed to a purely abstract mathematical method and the claim does not require any technical means”. | 6.1.1 Examination using Article 25.1(2) “If a claim relates to an abstract algorithm or a pure business rule and method, and does not contain any technical features, the claim is excluded as a rule and a method of intellectual activity under Article 25.1(2) and shall not be granted.” |

| Guidelines G-II 3.3 “If a claim is directed either to a method involving the use of technical means (e.g. a computer) or to a device, its subject-matter has a technical character as a whole and is thus not excluded from patentability under Art. 52(2) and (3)“. Case Law of the Boards of Appeal I.D.9.1.1 “In order to be patentable, the subject-matter claimed must therefore have a “technical character” or to be more precise – involve a “technical teaching”, ie an instruction addressed to a skilled person as to how to solve a particular technical problem using particular technical means.” | 6.1.2 Examination using Article 2.2 “If a claim for protection as a whole is not excluded under Article 25.1(2) of the Patent Law, then it is necessary to examine whether it is a technical solution specified in Article 2.2 of the Patent Law. When examining whether a claim containing algorithm or business rule and method features constitutes a technical solution, it is necessary to consider all the features in the claim as a whole. If the technical means recited in the claim uses the laws of nature to solve a technical problem, and thus obtains a technical effect in conformity with the laws of nature, the solution recited in the claim is a technical solution specified in Article 2.2 of the Patent Law.” |

| GL G-VII 5.4 “When assessing the inventive step of such a mixed-type invention, all those features which contribute to the technical character of the invention are taken into account. These also include the features which, when taken in isolation, are non-technical, but do, in the context of the invention, contribute to producing a technical effect serving a technical purpose, thereby contributing to the technical character of the invention. However, features which do not contribute to the technical character of the invention cannot support the presence of an inventive step (T 641/00). Such a situation may arise, for instance, if a feature contributes only to the solution of a non-technical problem, e.g. a problem in a field excluded from patentability (see G‑II, 3 and sub-sections).” | 6.1.3 Examination on novelty and inventive step “In the examination of novelty of an invention patent application containing algorithm or business rule and method features, all the features recited in a claim shall be taken into account, and here all the features include both technical features and algorithm or business rule and method features.” “In the examination of inventive step of an invention patent application that contains both technical features and algorithm or business rule and method features, the technical features should be considered as a whole with the algorithm or business rule and method features that have mutual supportive and interactive relations in function with the technical features. “Mutual supportive and interactive relations in function” means that algorithm or business rule and method features are closely integrated with technical features to form a technical means to solve a technical problem and can obtain a corresponding technical effect. For example, if the algorithm in a claim is applied to a specific technical field and can solve a specific technical problem, then it can be considered that the algorithm features and technical features have mutual supportive and interactive relations in function, and the algorithm features become a part of the adopted technical means, in the examination of inventive step the contribution of the algorithm features to the technical solution should be considered. In another example, if the implementation of business rule and method features in a claim requires an adjustment or an improvement of technical means, then business rule and method features and technical features could be considered to have mutual supportive and interactive relations in function, and in the examination of inventive step the contribution of business rule and method features to the technical solution should be considered. |

CNIPA examples

Section 6.2 provides 10 examples illustrating the application of the new guidelines in various scenarios from both positive and negative aspects. Examples 1 to 6 demonstrate whether the subject matter in the claimed invention is patentable. Example 1 relates to a method for establishing an abstract mathematical model, which should be excluded from patentability under Article 25.1(2). Examples 2 to 6 discuss what constitutes a technical solution in the fields of AI, business models and blockchain specified in Article 2.2 of the guidelines.

For instance, example 4 describes a method for preventing blockchain business nodes from leaking user privacy data in the alliance chain network. This claimed invention addresses a technical problem of providing more secure blockchain data – business nodes only establish connections to limited objects, by carrying the Certificate Authority (CA) certificate in the communication request and configuring the CA trust list in advance to determine whether to establish a connection. Such technical means achieve the technical effect of securing communications between business nodes and reducing the possibility of business nodes leaking private data. Therefore, the solution in this example is a technical solution specified in Article 2.2.

In contrast, example 5 relates to a method for promoting users’ consumption. This method, however, does not constitute a technical problem because a computer is only executed to determine the rebate amount based on the user’s consumption amount according to the specified rules. Therefore, in this application, no technical means are used, and the only effect of this claimed invention is to promote users’ consumption. The subject-matter in this patent application thus is excluded from patentability.

Examples 7 to 10 demonstrate whether the subject matter in patent applications involves an inventive step, which will be compared with EPO’s examples in a later section.

| Section | Title |

| 6.1.1 Article 25.1(2) An abstract algorithm or a pure business rule and method? | Ex. 1 – A method for establishing a mathematical model |

| 6.1.2 Article 2.2 A technical solution? | Ex. 2 – A method for training a convolutional neural network model Ex. 3 – A method for using shared bicycles Ex. 4 – A communication method and device between blockchain nodes Ex. 5 – A method of consumption rebate Ex. 6 – A method for analysing an economic sentiment index based on electricity consumption characteristics |

| 6.1.3 Novelty and inventive step | Ex. 7 – A method for detecting the falling state of a humanoid robot based on multi-sensor information Ex. 9 – A method of logistics distribution Ex. 8 – A multi-robot path planning system based on a cooperative co-evolution and multi-group genetic algorithm Ex. 10 – A method for visualising the evolution of dynamic viewpoints |

EPO v CNIPA – patentable subject matter

For the purposes of comparison, these new guidelines (section 6.1.1 and section 6.1.2) relating to patentable subject matter appear to be close to the EPO’s approach (as compared in the following Figure 1 and in the previous Table 1).

EPO v CNIPA – inventive step

The EPO guidelines (GL G-VII 5.4) and the case law (T 641/00) distinguish between three groups of features:

i) technical features,

ii) non-technical features, and

iii) features which, when taken in isolation, are non-technical, but do, in the context of the invention, contribute to producing a technical effect serving a technical purpose, thereby contributing to the technical character of the invention.

When following the approach set out in the new Chinese guidelines for assessing inventive step (section 6.1.3), algorithm or business rule and method features may be equivalent to the features in the EPO’s group iii. It might be worth noting that the CNIPA currently only considers these two particular kinds of ‘non-technical’ features (i.e. algorithms or business rule and method features) to be able to contribute to inventive step. The CNIPA’s approach seemingly first considers whether algorithm or business rule and method features and more traditional ‘technical features’ interact with each other functionally in the context of the invention to solve a technical problem and result in a corresponding technical effect. If yes, then the contribution of algorithm or business rule and method features should be considered.

| EPO examples (inventive step) |

| 5.4.2.1 Example 1 – Method of facilitating shopping on a mobile device |

| 5.4.2.2 Example 2 – A computer-implemented method for brokering offers and demands in the field of transporting freight |

| 5.4.2.3 Example 3 – A system for the transmission of a broadcast media channel to a remote client over a data connection |

| 5.4.2.4 Example 4 – A computer-implemented method for the numerical simulation of the performance of an electronic circuit subject to 1/f noise |

Two CNIPA examples (example 7* and example 10** detailed in post-script) and two EPO examples (5.4.2.2 example 2 and 5.4.2.4 example 4) are selected to demonstrate whether technical features and algorithm or business rule and method features interact with each other functionally in the context of the invention.

In example 7, it is considered that algorithm features – i.e. the fuzzy algorithm in step (2) – are closely integrated with technical features (i.e. the robot information in step (1)), because the input parameters of the fuzzy algorithm are limited to the robot information to determine the stability state of the humanoid robot. In one EPO example (5.4.2.4 example 4), ‘the mathematically expressed claim features’ when considered in isolation, represent a mathematical method with no technical character. However, these features contribute to the technical character of the method because the claim is limited to a computer-implemented method in which this mathematical method serves a technical purpose of ‘circuit simulation’. In other words, the ‘mathematically expressed claim features’ and the technical features of ‘circuit simulation’ can be considered to interact with each other functionally in the context of the invention.

In example 10, the CNIPA explains that the technical means for visualisation could be used with different sentiment categorisation rules (the algorithm feature). Therefore, the sentiment categorisation rule and the visualisation method do not interact with each other functionally. Similarly, the EPO provides an example in its guidelines (5.4.2.2 example 2) in which the features defining a business method were ‘easily separable’ from the technical features of its computer implementation. Thus, the business method features and technical features cannot be considered to interact with each other functionally in the context of the invention.

Conclusion

To conclude, the new CNIPA guidelines bring some welcome clarity to what was a grey area of determining the patentability of an application involving business rules and methods, algorithms and mathematical methods. Previously, it was very common to see Chinese Examiners assessing inventive step based on divided features in a claim, and there was no clear guidance on how to examine ‘non-technical’ features. The new guidelines, therefore, tend to be more friendly to patent applicants because of the new ‘as-a-whole’ principle and the ‘interaction-consideration’ principle. This fast-track amendment indicates that, in order to keep up with the times, the CNIPA is maintaining a positive attitude towards AI and blockchain-related inventions.

Post-script

Example 7 *

Claim 1 recites

“A method for detecting the falling state of a humanoid robot based on multi-sensor information, which is characterized by the following steps:

(1) fusing attitude sensor information, zero-moment point ZMP sensor information and robot walking stage information to establish a sensor information fusion model with a layered structure;

(2) using the front and rear fuzzy decision system and the left and right fuzzy decision system to determine the stability of the robot in the front and rear direction, and the left and right direction respectively, the specific steps are as follows:

① determining the walking stage of the robot according to the contact between the robot support foot and the ground and offline gait planning;

②applying fuzzy inference algorithm on the position information of ZMP;

③applying fuzzy inference algorithm on the pitch or roll angle of the robot;

④ determining the output membership function;

⑤ determining fuzzy inference rules according to steps ①~④;

⑥ de-fuzzifying.“

D1 is considered as the closest art and discloses step (1) of the method. Therefore, the difference between D1 lies in step (2) – i.e. implementation of the fuzzy decision algorithm. Compared to D1, the technical problem solved by the claimed invention is how to determine the stability state of the robot and accurately predict its possible fall direction. The altitude information, ZMP (Zero Moment Point) position information and walking stage information in step (1) are used as input parameters, and the fuzzy algorithm in step (2) outputs information to determine the stability state of the humanoid robot, which provides a basis for further accurate posture adjustment instructions. Therefore, the algorithm features and technical features have mutual supportive and interactive relations in function, and they are closely integrated and jointly constitute a technical means to solve a technical problem and thus obtain a corresponding technical effect.

Example 10 **

Claim 1 recites

“A method for visualising the evolution of dynamic viewpoints, comprising:

Step 1 – a computing device determines a sentiment membership and sentiment category of the information in the collected information set, the sentiment membership of the information indicates how likely the information belongs to a sentiment category;

Step 2 – the sentiment category is positive, neutral, or negative, the specific categorisation method is: If the value r of the number of likes p divided by the number of dislikes q is greater than the threshold value a, then the sentiment category is considered as positive, if the value r is less than the threshold b, then the sentiment category is considered as negative, if b≤r≤a, then the sentiment category is neutral, wherein a>b;

Step 3 – based on the sentiment category of the information, the geometric layout of the sentiment visualisation of the information set is automatically established, the horizontal axis represents the time of information generation, and the vertical axis represents the amount of information belonging to each sentiment category;

Step 4 – the computing device colours the established geometric layout based on the sentiment membership of the information, and colours the information on each sentiment category layer according to the gradual order of the information colour.”

D1 discloses a sentiment-based visualisation analysis method, where time is represented as a horizontal axis, the width of each colour band represents a measure of sentiment at that time, and different colour bands represent different sentiment.

The difference between the solution of the claimed invention and the closest prior art D1 is the new sentiment categorisation rule proposed in step 2. It should be noted that the same technical means for colouring could be used with different sentiment categorisation rules. Therefore, the sentiment categorisation rule and the visualisation method do not have mutual supportive and interactive relations in function.

In addition, the problem of ‘visualisation’ has been solved in D1. Compared to D1, the claimed invention only proposes a new rule for sentiment categorisation, which does not actually solve any technical problem or make a technical contribution to the art. Consequently, the claimed technical solution of the claimed invention does not involve an inventive step in light of D1.

[1] Similar to Information Superhighway and Industry 4.0, the Chinese government has created its own “Internet Plus” initiative to transform, modernize and equip traditional industries to join the modern economy.

In its recent decision, the EUIPO Fourth Board of Appeal overturned the Opposition Division’s earlier decision in opposition proceedings concerning ex-professional footballer Jürgen Klinsmann and Panini Societá Per Azioni (‘Panini’), which is perhaps best known for producing collectable stickers of footballers and sticker albums.

The marks

The case concerned Mr Klinsmann’s EU designation of international registration no. 1384372 for the above mark for a range of goods in classes 16. 25 and 32 (including printed matter, clothing and beers and non-alcoholic beverages, respectively) and services in class 41 (including sporting activities). Panini opposed the designation on the basis of the following marks:

1. Italian reg. no. 1539690 for services in class 41 (including sporting activities);

2. EU designation of international reg. no. 1282870 for goods in class 32 (including beers and non-alcoholic beverages);

3. Italian reg. no. 1561953 for goods in classes 16 and 25 (including stickers and clothing articles, respectively);

4. Italian reg. no. 1063937 (representation of mark not provided) for goods in classes 16 and 25 (including stickers and clothing articles, respectively);

5. EU reg. no. 4244273 for goods in class 16 (including stickers); and

6. EU reg. no. 4244265 for goods in class 16 (including stickers).

The opposition proceedings

Grounds 1-4 were based on the allegation of a likelihood of confusion between those marks and Mr Klinsmann’s. Grounds 5 and 6 were based on Panini’s alleged reputation in those marks and the allegation that Mr Klinsmann’s use of his mark would take unfair advantage of, or cause detriment to, that reputation.

The Opposition Division found a likelihood of confusion in respect of grounds 1, 2 and 3 and therefore refused the application for all of the contested goods/services and did not proceed to examine the opposition under grounds 5 and 6.

Mr Klinsmann appealed the decision asserting that the marks are dissimilar.

The appeal proceedings

The Board of Appeal found that the respective marks were, as Mr Klinsmann alleged, dissimilar on the basis that Mr Klinsmann’s mark differs from Panini’s marks in that:

- it only consists of a black and white sketch without any contours within the sign itself, which is just black;

- there is a circle around the black sketchy element;

- the silhouette is markedly different in position and direction (the thickest stroke being vertical upwards).

The Board found that “the impression of both marks as a whole is markedly different. There is not even one single ‘element’ that could be singled out from the earlier mark and then be found to ‘match’”. In the absence of any word element, no oral assessment could be performed.

The Board also continued that “the representation of a football player, as a concept, is weak for goods that have to do with football and sports in general. That extends to ‘clothing’ insofar as sportive clothing is covered, and to Class 16 as regards the goods for which the opponent claims an actual use (and reputation), namely stickers of footballers and football books, almanacs or albums”. It found that Mr Klinsmann’s mark would not be perceived unambiguously as a football player, and therefore has no clear concept; as a result there was no conceptual similarity between the marks.

As the Board found that the marks were visually and conceptually dissimilar, it could not find a likelihood of confusion or unfair advantage/detriment. Particularly noteworthy is the fact that, as Panini failed to file adequate proof of use of the mark under ground 6 (which it was requested to do by Mr Klinsmann), the opposition was unfounded in that regard. The same was true for the mark under ground 4.

Commenting on the decision, Harry Rowe, managing associate in the Mathys & Squire trade mark team, said: “As a Tottenham Hotspur fan (Klinsmann being a club legend) and a lover of all things trade marks, this case particularly piqued my interest. The case represents an important example of the narrower scope of protection afforded to figurative marks (as compared to word marks); it shows that one cannot merely rely on slight visual and conceptual similarities for a successful opposition. It also highlights the importance of filing cogent evidence of use (and the need to keep records of such evidence in the event it is required in opposition or cancellation proceedings).”

A version of this article was published in The Trademark Lawyer magazine in October 2020.