In the rapidly evolving world of cosmetics, biotherapeutic molecules, which were once confined to medical and pharmaceutical settings, are now making their way into skincare products, reshaping the landscape of anti-ageing treatments, skin repair and regenerative aesthetics.

Recent trends include the use of stem cell extracts, exosomes, polynucleotides, collagen and endonucleases in skincare products to stimulate the body’s natural healing processes. Moving beyond traditional fillers and Botox, new treatments are harnessing the body’s own biological pathways to restore skin vitality, volume and health. The credibility of using biotherapeutics in cosmetic applications has been bolstered by the formation of the Royal Society of Medicine’s Section of Aesthetic Medicine and Surgery (SAMAS), which was formally established on 1 October 2024. This development signals a growing acceptance of aesthetics within the wider medical community.

In this article, Partner Samantha Moodie and Associate Clare Pratt look at some of the key biotherapeutic molecules gaining traction in cosmetics and provide guidance on effective strategies for protecting these innovations in Europe through the patent system of the European patent office (EPO).

What are the latest trends in biotherapeutic cosmetic products?

Stem Cells

Stem cells have become a buzzword in premium skincare. They are used in cosmetics primarily for their regenerative and anti-ageing properties, although the products typically contain stem cell-derived ingredients such as conditioned media or extracts, rather than live stem cells. Stem cell therapies are being explored for skin rejuvenation, scar reduction, hair restoration and breast reconstruction, among other areas. Stem cell extracts and conditioned media can be applied topically (either alone or in combination with other treatments such as microneedling or laser ablation) or delivered via injection to achieve targeted regenerative effects.

Exosomes

Exosomes are extracellular vesicles, typically 30–150 nanometres in diameter, secreted by a range of cells including adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), immune cells, epithelial cells and even plant cells, referred to as plant-derived extracellular nanoparticles (PDENs). These vesicles carry bioactive cargo such as proteins (e.g. growth factors and cytokines), peptides, lipids, RNA (including mRNA and microRNA), and DNA. Crucial to intercellular communication, aesthetic medicine is increasingly harnessing exosomes as a natural means of restoring skin volume and promoting regeneration to rejuvenate the skin, reduce inflammation, enhance elasticity and hydration, and diminish fine lines, wrinkles and pigmentation. Typically administered via topical serums or creams, they are often combined with microneedling or laser treatments to enhance transdermal penetration and support post-procedural recovery.

Polynucleotides

Polynucleotides (PNs) are increasingly being used in aesthetic dermatology and high-end cosmetics. PNs are long chains of nucleotides derived from DNA or RNA and when injected or applied topically, are thought to promote tissue repair, increase hydration, and improve skin elasticity by stimulating fibroblast activity and collagen synthesis. Originally developed for wound healing and orthopaedics, polynucleotide technology has expanded into aesthetic dermatology.

Collagen

Collagen is the most abundant protein in the skin and connective tissues, providing structure, firmness and elasticity. Its natural decline with age leads to wrinkles, sagging and thinner, drier skin. To address this, topical collagen is often used to hydrate the skin and form a moisture-retaining film, creating a smoother, plumper appearance. Some products use collagen fragments (peptides) or compounds that stimulate collagen synthesis, such as retinoids, vitamin C and peptides (acetyl hexapeptide-3). A growing trend known as “collagen banking” promotes early intervention through skincare, treatments and lifestyle habits to build and preserve collagen reserves, aiming to delay the visible effects of ageing.

Endonucleases and genome-editing enzymes

Endonucleases and genome-editing enzymes, including CRISPR-associated nucleases, are a class of enzymes that can cut DNA strands at specific sites. While primarily known for their gene-editing potential in medicine, certain DNA repair enzymes are now being explored in cosmetics to correct UV-induced DNA damage in skin cells, positioned as anti-ageing or post-sun exposure treatments. Commercial products using liposome-encapsulated endonucleases claim to support DNA repair mechanisms, although the field remains nascent and scientifically complex.

Why is patent protection important in the cosmetic industry?

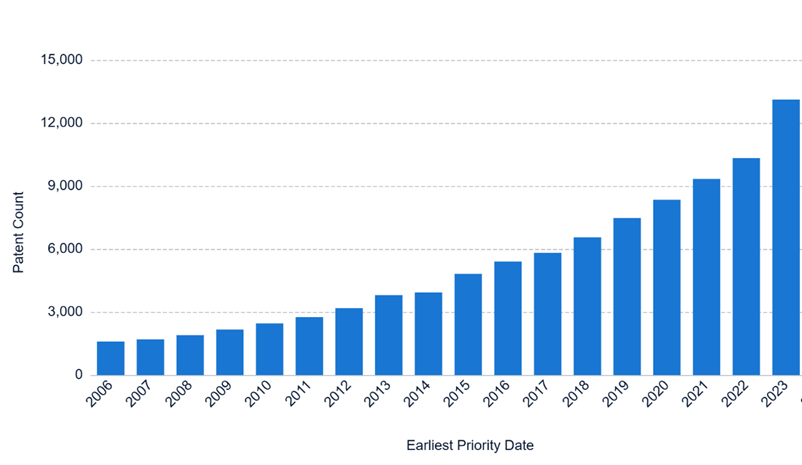

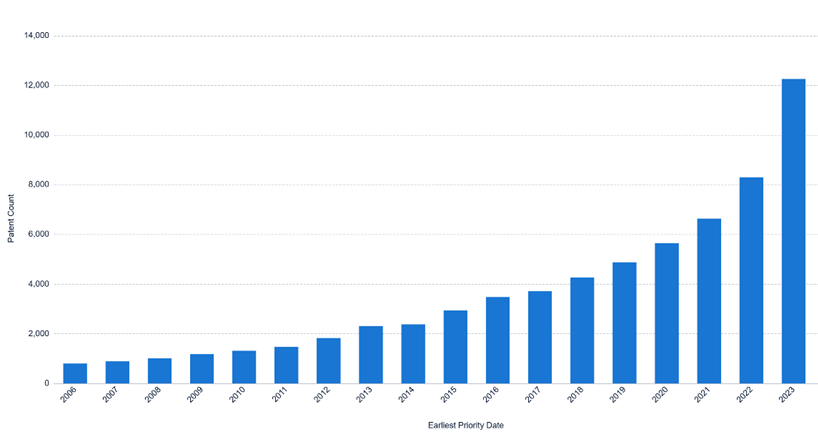

Research and development in the cosmetics industry can be costly, especially research relating to the use of biotherapeutic molecules. Patents play a crucial role in helping companies recover these investments by granting them the legal right to prevent others from making, using, selling or importing their inventions without permission. In addition to protecting innovation, patents offer a competitive advantage, discourage imitation, and can generate commercial value through licensing agreements. Securing intellectual property is often a prerequisite for attracting investment. Recent trends indicate that cosmetic companies are increasingly relying on patents to safeguard their innovations. The number of active patent applications filed globally in the field of cosmetics has grown year on year in the period between 2006 and 2023 (see Figure 1), and there has been a recent surge in the number of active patent applications relating to biotherapeutic cosmetics (see Figure 2).

Figure 1: Active published patent filings, including granted patents, in the field of cosmetics worldwide. The bar chart displays patent families between 2006-2023 for IPC codes relating to “cosmetics” (see methodology).

Figure 2. Active published patent filings, including granted patents, relating to biotherapeutic cosmetics worldwide. The bar chart displays patent families between 2006-2023 for IPC codes relating to “biotherapeutic cosmetics” (see methodology).

What aspect of biotherapeutic cosmetics can we protect in a patent?

Patents can be obtained to protect various aspects of biotherapeutic cosmetics, including the products per se, and their formulations, manufacturing processes and cosmetic uses. The incorporation of biotherapeutics into cosmetics blurs traditional boundaries between medicinal and cosmetic products. This grey area requires careful consideration during patent drafting and prosecution. Therefore, a key question for inventors working in these developing areas of technology is how best to gain patent protection. The optimal patent strategy will depend on whether a product, its formulation or the process for its manufacture is new; whether a new use for a known product has been discovered; and whether the intended use is purely cosmetic or also has a therapeutic effect.

Product claims

Product claims protect the composition or structure of a novel cosmetic product, such as a newly identified plant extract or a newly developed stem cell extract. Product claims are useful in a patent because they grant the Applicant the right to prevent others from making, using, selling or importing the claimed product. To obtain a product claim, the Applicant must demonstrate that the product is novel and inventive. Sufficient information should be provided in the patent application to enable preparation of the claimed product. For example, a product claim may be directed towards an anti-wrinkle cream containing a novel plant-derived molecule that achieves an improved anti-wrinkle effect.

Process claims

Process claimsprotect the method of making a cosmetic product, using, for example, a chemical, biotechnological or mechanical procedure. A process claim in a patent grants the Applicant the right to prevent others from using the claimed process and from using, selling or importing a product obtained directly by the claimed process. To obtain a process claim, the Applicant must demonstrate that the process is novel and inventive, and sufficient information should be provided in the patent application to enable the claimed process to be carried out. For example, a process patent may cover a new method of extracting a natural compound from a plant and incorporating it into a cosmetic product, or a new process for preparing a stem cell extract with improved cosmetic effect.

For many biotherapeutic cosmetics, innovation often stems from discovering new uses for known biological molecules. In this situation, the molecules themselves are not novel and the best approach for obtaining patent protection is to seek protection for the newly identified use. Use claims, therefore, protect a new or improved effect of a cosmetic product, and they grant the Applicant the right to prevent others from using the product for the claimed use.

To obtain a use claim, the Applicant must demonstrate that the claimed use is novel and inventive. Furthermore, sufficient information should be provided in the patent application to enable preparation of the product and use of it to achieve the desired cosmetic effect. The Applicant may also be required to demonstrate that the claimed cosmetic use does not involve an inextricably linked therapeutic effect, which would be considered unpatentable at the European Patent Office (EPO). (See Appendix 1)

To prove infringement of a use claim, the Patentee must demonstrate that an alleged infringer is using the product for the claimed cosmetic use. Use claims can therefore be more challenging to enforce than product or composition claims.

Composition claims

Composition claimsare another useful claim category for protecting a cosmetic product when thebiological molecule itself is known, but the formulation of the product is novel. Composition claims grant the Applicant the right to prevent others from making, using, selling, or importing the claimed formulation. To obtain a composition claim, the Applicant must demonstrate that the composition (or formulation) is novel and inventive, and sufficient information should be provided in the patent application to enable preparation of the claimed composition. Composition claims may need to include reference to the specific concentrations or ratios of the components that are required to achieve the desired cosmetic effect to be considered patentable. Composition claims are easier to enforce than use claims because infringement can be determined based on the composition of the alleged infringing product, rather than how it is used.

Conclusion

Hence, there are a range of ways in which innovations in the field of biotherapeutic cosmetics can be patented. In addition, current trends in patent filings indicate that cosmetic companies are increasingly leveraging the patent system to safeguard their inventions.

In our next article, we will take a closer look at ‘cosmetic use’ claims. As noted in this article, such claims must be drafted with particular care to avoid falling within the EPO’s exclusions relating to therapeutic methods. We will explore the relevant EPO case law on cosmetic use claims and provide practical guidance for drafting robust and compliant patent applications in this evolving area.

Appendix

- (Under the European Patent Convention (EPC), patents cannot be granted for methods of treating the human or animal body by surgery or therapy, or for methods of diagnosis practised on the human or animal body (Article 53(c) EPC). The exclusion under Article 53(c) EPC does not apply to cosmetic uses or treatments. When a compound is identified as having a new cosmetic use, non-therapeutic method claims can be pursued at the EPO. For example, claims may be directed towards: “Use of compound X in the cosmetic treatment of Y”, “cosmetic use of X for purpose Y” or “non-therapeutic use of X for purpose Y”. In such claims, the “cosmetic use” or “non-therapeutic use” language serves as a disclaimer to exclude any effect that may be therapeutic in nature and would otherwise fall under the exclusion from patentability set out in Article 53(c) EPC. However, this disclaimer language is only permissible if the claimed cosmetic effect is not inextricably linked to a therapeutic effect that is achieved when the molecule is used as specified in the claim. In Part 2 of this article, we will further consider the relevant EPO regulations and case law governing cosmetic use claims, offering practical drafting guidance for patent applications in this area.)

Methodology

The data presented in this article was obtained using Patsnap by comparing active patent “simple patent families” between 2006 and 2023 related to specific IPC codes. A simple patent family is a collection of patent documents that are considered to cover a single invention. Patent applications that are members of one simple patent family will all have the same priorities, and continuations and divisionals will be placed in a patent family with the parent application. The IPC codes used to filter the searches were: “field of cosmetics” A61Q and A61K 8/00 in comparison with “biotherapeutic cosmetics”: A61Q and A61K/8/02, A61K/8/03, A61K/8/04, A61K/8/06, A61K/8/11, A61K/8/14, A61K/8/18, A61K/8/64, A61K/8/65, A61K/8/66, A61K/8/67, A61K/8/72, A61K/8/73, A61K/8/88, A61K/8/97, A61K/8/98, and A61K/8/99.