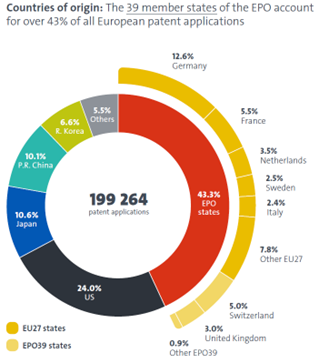

27.3% of all applications filed at the European Patent Office (EPO) in 2024 originated from China, Japan, and Korea. Almost all of such applications claim priority from patent applications filed locally in those countries, which are normally prepared and filed in the local languages. This means that the content of such applications must be translated into an EPO official language (normally English) either when a corresponding European patent application is filed or a PCT application enters the regional phase.

The intricacies of translation

Translation issues can invalidate patents in Europe. Priority claims are only valid if a priority document contains a clear and unambiguous disclosure of a claimed invention. This is a very strict test and minor differences in language can lead to allegations that a claimed invention was not disclosed in an earlier priority application.

Similarly, when a European patent application is derived from a PCT application, whether or not matter is added during prosecution is judged against the content of the original PCT application rather than the content of a translation filed on entry to the regional phase. Again, the EPO’s test for added matter is a strict one – did the original PCT application contain a clear and unambiguous disclosure of a claimed invention? Minor changes in language can result in a patent application failing such a test.

Whenever such issues arise, the EPO is forced to consider the content of documents written in languages other than the working languages of the office. When dealing with languages such as Chinese, Japanese and Korean which are far removed from the European languages with which the EPO is normally familiar, knowledge of how languages work and the quality of translations used can become crucial.

The Opposition against EP2022349

The Opposition against EP2022349, filed by seven Opponents, illustrates how unsatisfactory translations can jeopardise the validity of patents before the EPO.

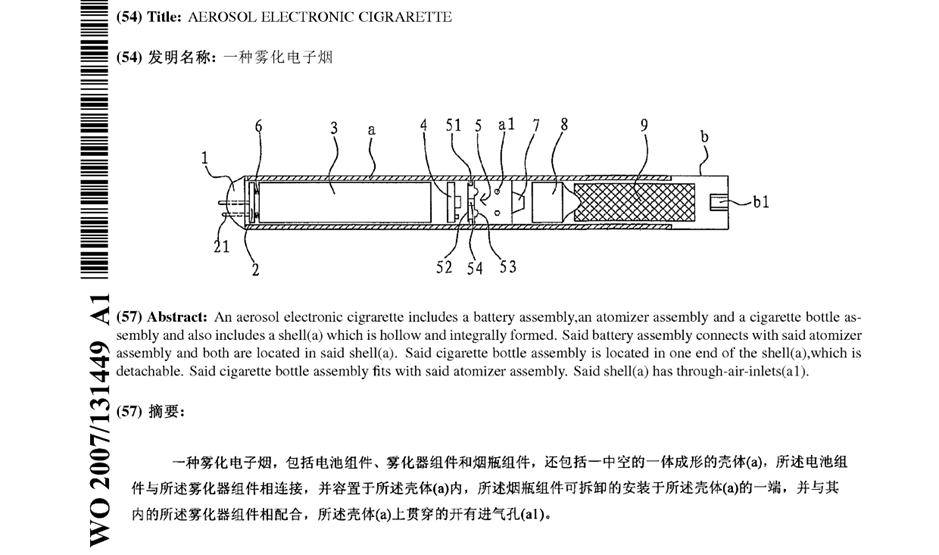

EP2022349 relates to an early vaporiser design for electronic cigarettes. The patent was involved in litigation in the UK and Germany among various e-cigarette companies in the mid-2010s because it represents an early example of an e-cigarette patent which covered modern e-cigarette designs.

The patent was based on a PCT application WO2007131449, originally drafted in Chinese. Unfortunately, the Chinese text itself was less than satisfactory, and the English translation submitted on entry into the European phase was also of limited quality. This later led to numerous added matter issues under Article 123(2) EPC.

Translation issues and Added Matter disputes

Air Inlet(s)

The Opponents objected that the application did not disclose an electronic cigarette having a single air inlet. The patentee explained that the Chinese characters 进气孔used to refer to the air inlets in the original Chinese implicitly referred to “one or more air inlets” because in Chinese if a specific number of air inlets was to be intended this would need to be made explicit in the Chinese (e.g. 一个进气口 one air inlet or 两个进气孔 two air inlets).

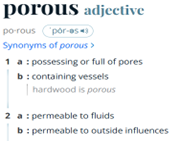

“Perforated” vs “Porous”

The original translation rendered a key term 多孔 (“Duo Kong” two characters literally having separate meanings as “many” and “holes”) as “perforated,” later corrected to “porous.” The Opponents objected that this correction introduced added matter, a point that was upheld by the EPO in a related divisional case.

“Frame” vs “Support Member”

The Opponents objected that 架体 ( “Jia Ti” two characters literally having separate meanings as “frame” and “body”) had a restricted meaning of “frame” and that the translation of 架体 as “support member” added matter.

Conjunctions and Prepositions

Even small linguistic nuances triggered disputes. For example, the location of the air channel in the claim was objected to with an Opponent contending that the original Chinese referred to the air channel being located “in the centre on one end surface of a cigarette holder shell” rather than “in the centre of one end surface of a cigarette holder shell”. This objection was refuted by the patentee with an explanation that in the original Chinese it was clear the central air channel was located in the centre of the surface of the cigarette holder shell.

Resolution and practical lessons

Ultimately the EP Opposition against EP2022349 ended without a formal conclusion on these translation disputes, as the case was withdrawn prior to a final decision. Nevertheless, the case provides a valuable example of issues which can arise when an inaccurate translation is used as well as the manner in which such objections may be overcome – in this case affidavit evidence was filed to explain the differences between English and Chinese.

The EP2022349 Opposition is a cautionary tale for patentees, attorneys, and translators alike. Above all, it reinforces the importance of investing in precise translations and expert linguistic input at the earliest stages of international patent prosecution.

Partner Nicholas Fox has been featured in an exclusive titled “Uptake of Unitary Patents Almost A Third of EU Total” in Law360 and “Report reveals unitary patent strategy of IT and engineering leaders” in the World Intellectual Property Review. This is following Mathys & Squire’s recent report, The Use of the Unitary Patent System in IT & Engineering by Partner Nicholas Fox and Associate Maxwell Haughey.

In these articles, Nicholas Fox offers deeper insights into why industry players within the field of IT & Engineering are becoming more open to the Unitary Patent system, whilst noting that some may still remain cautious on account of certain factors such as the likelihood of patent disputes and the cost of translation.

Read the extended press release below.

EU’s new unitary patents now account for 28% of all new patents granted – but major companies split on patent strategy

The EU’s new unitary patents (UPs) now account for 28% of all European patents granted in 2025 to date, up from 26% last year and 18% in 2023*, says leading intellectual property (IP) law firm Mathys & Squire LLP. Of the 19,000 European patents granted in 2024, 5,300 were maintained as UPs rather than as a bundle of national rights.

Mathys & Squire says that the Unitary Patent System, introduced in 2023, is cost-effective if the objective of patent proprietors is to obtain wide geographical protection in Europe. The cost of maintaining a Unitary Patent is roughly equivalent to the cost of maintaining patent protection in four European countries whilst giving inventors a single patent that applies to eighteen EU member states.

In some circumstances unitary patents can, however, be riskier than maintaining rights as a bundle of national patents. The primary risk is that a single court decision could see the patent revoked in all countries where it has effect.

According to Mathys & Squire’s Use of Unitary Patent System: IT & Engineering report, uptake of UPs varies significantly by technical field. The highest uptake of UPs is in civil engineering, where 39% of European patents granted in 2024 were maintained as UPs, up from 28% in 2023. Within the sectors sampled, the Defence sector had the lowest uptake with only 11% of defence patents granted in 2024 being maintained as UPs, that being an increase from 6% of patents granted in 2023.

Nicholas Fox, Partner at Mathys & Squire and European Patent Attorney, explains that uptake of UPs is typically lower in sectors requiring patents in only a few countries. The Oil and Gas sector is a good example of this. In many cases, oil and gas companies tend to only need patent protection only in the North Sea and hence often only in the UK and Norway. Such companies gain little from using UPs. Businesses in sectors needing broader geographical protection benefit more.

Says Fox: “In many sectors, Unitary patents are fast becoming one of Europe’s main patent types. They’re increasingly displacing the old ‘bundle’ system that requires separate validation in each country. They can be a cost-effective way of securing broad geographic protection for an invention in Europe. Adoption of unitary patents is, however, uneven across different technologies and amongst different companies even when companies operate in similar fields.”

Small businesses make proportionally greater use of unitary patents than large businesses

The slow uptake of UPs in some fields is partly due to translation requirements. In many IT and Engineering fields (e.g. telecoms), European Patents are typically maintained in countries where full translation isn’t needed, including the UK, Germany and France. Maintaining rights only in these countries can be sufficient for many companies operating in these fields.

The need for full translations to obtain a UP can be a significant factor behind the slow adoption rate of UPs in IT and Engineering. For companies with large portfolios, costs can mount up, as patents prosecuted in German or French must be translated into English, and those in English must be translated into any EU language.

This is backed up by research which finds that small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), who normally have far smaller patent portfolios are making greater use of the unitary patent than large businesses. SMEs accounted for just 23% of European patent filings in 2024 but obtained 36% of all UPs. Large businesses accounted for 69% of all European patent filings but only 57% of UPs. Universities and public research organisations account for the remainder of filings and UPs.

Fox says another reason for lower uptake among large businesses is uncertainty over the role of the new Unitary Patent Court (UPC). The UPC centralises patent disputes in a single court with authority across Europe. However, Fox says these concerns should ease as the court builds a track record of high-quality and predictable rulings.

Adds Fox: “Small businesses appear more enthusiastic about the new unitary patent system. The annual renewal fees to maintain multiple national patents account for a bigger share of their budgets than for large businesses.”

“Some large companies have taken a wait-and-see approach to the UPC. The UPC’s rulings have been consistent so far, giving businesses greater confidence in the system. We therefore expect large businesses to gradually increase their use of the unitary patent system.”

“Businesses are still weighing the costs and benefits of the new system. Broad European coverage can be attractive, but in fields with more frequent disputes, the risk of one court deciding everything across Europe is enough to make them hesitate.”

Leading businesses in tech and engineering take sharply different approaches

Mathys & Squire’s research shows significant variations in UP uptake in different sectors and between companies operating in the same sector.

In Automotive and Aerospace, Mercedes-Benz and Airbus have obtained UPs, while BMW, Boeing and Rolls-Royce have yet to meaningfully engage with the new system. Across the wider transport sector, UPs made up 21% of all European patents granted in 2024, up from 14% in 2023.

Similar variations are to be found within the Defence sector. Overall, engagement with the Unitary Patent system in the Defence sector has been limited with only 10% of European Patents in the sector granted in 2024 being maintained as UPs. Many Defence companies have either not engaged at all with the new UP system or have been highly selective in doing so. By way of example, only 6% and 3% of European patents granted in 2024 to Leonardo and Rheinmetal respectively were maintained as UPs. In contrast, BAE Systems chose to maintain 36% of their patents granted in 2024 as UPs and ThyssenKrupp chose to maintain all its European patents granted in 2024 as UPs.

In Digital Communications, UP uptake has also lagged, climbing from 11% in 2023 only to 18% in 2024. Ericson, and Samsung each converted large numbers of their European patents into Unitary Patents. But as with other areas of technology there is significant variation amongst the biggest filers. Some companies, like Lenovo, maintained all of their European patents granted in 2024 as unitary patents, while Google and Microsoft obtained no unitary patents and instead maintained their European patents as bundles of national rights.

The research also shows some large companies vary their level of engagement strategies across different technologies. For example, Qualcomm maintained roughly two-thirds of its semiconductor patents as UPs in 2024. But in the field of digital communications, the share of patents maintained by Qualcomm as UPs was only 30%.

* The 2023 figure shows the share of European patents that were filed as UPs since the regime came into effect

Mathys & Squire Partners Chris Hamer and Laura Clews, and Head of Consulting Lyle Ellis have been featured in “Patents on a Plate” by Protein Production Technology International (PPTI). They provided commentary on how to protect innovations and manage intellectual property in the alternative proteins industry.

The article in PPTI highlights how intellectual property is a crucial pillar of the industry, as innovation within protein production is evolving rapidly in response to growing consumer interest in sustainable and ethical food, from fermentation-based proteins to cell-cultured alternatives. Intellectual property assets, including patents, trade marks and trade secrets, are vital in preventing competitors from exploiting your innovation, but they also play a significant role in shaping how innovation develops.

Partners Chris Hamer and Laura Clews discuss how recent years have seen food companies demonstrating a greater recognition of the importance of IP, for example in attracting investors, as well as the necessity of a robust IP portfolio, spanning multiple jurisdictions, for start-ups in the industry. Head of Consulting Lyle Ellis touches on the tricky balance between maintaining exclusivity and ensuring that key technologies are accessible to others in the sector, evaluating the trade-off between patents and trade secrets.

You can read the full article here.

An interview with Mathys & Squire Partner Stephen Garner was recently featured in ‘The flaw that landed Sanofi a win in the rare disease space’ by Life Sciences Intellectual Property Review. He provided commentary on Sanofi’s wins against Centogene at the European Patent Office in cases for which he was lead counsel.

The cases concerned patents for monitoring and diagnosing Gaucher’s disease, a rare, inherited metabolic disorder, by tracking the levels of a biomarker. Ultimately, the Technical Board of Appeal revoked both patents on account of a lack of key information about how to obtain the antibodies necessary for detecting the biomarker.

In the article in LSIPR, Stephen Garner, who worked alongside Partner Alexander Robinson on the cases, shares his insights on the EPO’s approach to patent disputes and how they tackled the challenges which arose in these cases. His interview highlights how patent attorneys must view each case on its own merits. Although biomarkers are generally patentable at the EPO, in this instance, the biomarker was not a standard antigen, which called into question the use of immunoassays in the claims.

To read the full article click here.

On 15th July 2025, the UK Government released a consultation on SEPs (Standard Essential Patents). With the aim of facilitating innovation for UK businesses in the digital technology industry, the government issued the consultation to better understand implementers and holders’ attitudes towards the SEP ecosystem and what changes will be the most effective in tackling current obstacles to innovation.

Standard Essential Patents

Standard Essential Patents (SEPs) are patents which are essential to a technical standard, e.g. standards developed by IEEE, 3GPP and the like. Technical standards set out how devices interact with one another, such as during the process of wireless communication. The use of these standards enables all devices to seamlessly communicate with one another, regardless of their manufacturer or where they are located in the world. Hence, holders of SEPs must make their patents easily available by adhering to the terms of fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) licensing. A transparent framework for and access to SEPs is vital to facilitate innovation in such technological fields, as well as ensure that different products and services produced by different companies are all safe and compatible.

The use of devices which can wirelessly communicate with other devices is continuing to rise, as Internet of Things (IoT) devices and vehicular wireless communications become more prevalent. Therefore, a greater number of industries and businesses are relying on technical standards so that their devices can communicate with other devices, resulting in an increased interest in SEPs.

Challenges in the SEP ecosystem

The consultation notes that the current ecosystem is somewhat challenging, particularly for smaller enterprises. As the importance of and need for SEPs in more industries rise, any limitations in the SEP framework could significantly impede innovation in technology.

For example, the consultation remarks that there is lack of transparency during SEP licensing processes, especially with regards to pricing, as business privately negotiate license rates (although there is more transparency in markets with developed SEP practices, such as in the field of cellular communications). The nature of these private negotiations leads to license rates remaining private, e.g. through NDAs. There is also no fixed procedure for establishing the rate, and this can result in unnecessarily lengthy timeframes for license agreements, as well as potential overpricing.

The possibility of knowledge and information gaps between implementers and holders of SEPs also extends to the definition of essentiality. Licensees and implementers may not have access to the information needed to determine which patents are truly essential to a standard. The consultation notes that more patents are declared to be SEPs than are actually needed for a technological standard, with the percentage of truly essential declared SEPs being potentially as low as 25-40%. This could be because patent holders have to divulge essentiality very early in the technical standard development process, pushing them to make assumptions. Again, this increases potential costs for licensees as they need to conduct extensive searches to understand which SEPs they must license to implement a standard. Moreover, the legal uncertainty may discourage businesses from entering the market at all.

The consultation and its proposals

Driven by a goal to boost and facilitate innovation in the UK, the consultation focuses on how the SEP ecosystem in the UK can operate more effectively and more transparently to support UK businesses. In releasing the consultation, the government’s main objective is to ensure implementers, especially SMEs, can successfully navigate the SEP ecosystem and FRAND licensing. They hope to explore ways of improving transparency, in terms of both pricing and essentiality, as well as procedures which could enhance efficiency in dispute resolution.

Transparency

The government proposes two main new mechanisms which attempt to address the national challenges mentioned in the previous section.

The Rate Determination Track (RDT) is one such mechanism which the government suggests introducing to the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC). The RDT, if initiated, would be a simpler and more efficient approach to the process of determining the correct license rate. The system would act as a supplement to the existing Small Claims and Multi Claims track.

Another mechanism referred to in the consultation is the provision of searchable standard-related patent information. At present, information on SEPs, including information regarding ownership of those SEPs, is often reported and updated inconsistently, and divulged in a fragmented fashion over multiple sources. To consolidate this information, the consultation proposes the introduction of an additional search function to the One IPO Search service for SEPs. The government is also gathering opinions on whether an essentiality assessment service through the UKIPO would be necessary to further improve transparency in what constitutes an SEP.

Litigation

Finally, the government is also seeking input on various suggestions which they believe will reduce the likelihood of litigation and improve dispute resolution. One such proposal is the implementation of a specialist pre-action protocol for SEP disputes which would potentially reduce information asymmetry, preventing disagreements during licensing and the need for litigation. In addition, the government is requesting feedback on the efficacy of current remedies offered in SEP litigation and on the level of awareness of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) services.

Author’s comment

It is positive to see the government take steps to consult with users of the SEP ecosystem. However, it remains to be seen whether the steps proposed in the consultation will result in meaningful change, particularly for small enterprises as intended. Specifically, IPEC trials, which small enterprises are most likely to favour, are already extremely efficient in respect of the time and costs involved. It is not clear how the proposed RDT could be more efficient in either respect.

A centralised repository of searchable standard-related patent information could be useful, but it remains unclear who will decide which cases are essential and added to the repository (and which cases are not), and how that difficult and subjective decision will be made.

It will be interesting to see what the government proposes once the responses to the consultation have been reviewed. The deadline for responding to the consultation is the 7th of October 2025 and, therefore, further announcements are expected next year.

You can read the full consultation here.

Investment Surges in AI-Driven Drug Discovery

Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as one of the most transformative technologies in recent years. The European Medtech sector saw a surge in investor interest in early 2025, dominated by AI-powered solutions. In Q1 alone, AI startups secured 25% of all European venture capital funding, with AI for drug discovery emerging as one of the leading segments.

Earlier this year, the UK government announced a £82.6 million investment into cancer research using AI, showing a dedication to harnessing the power of AI for cancer care and drug discovery. In June, the Nuffield Department of Medicine announced a new consortium, based in Oxfordshire, which will generate the world’s largest trove of data on how drugs interact with proteins for training AI models. 20 times larger than anything collected over the last 50 years, this collection will allegedly cut drug discovery costs by up to £100 billion.

Confidence in the potential of AI to solve healthcare’s greatest problems is growing, especially in areas like small-molecule drug and antibody design. With pressure to deliver faster, more targeted therapies, AI is becoming a central engine of biomedical innovation.

AI’s Transformative Role in Drug Discovery

AI is revolutionising how we discover new drugs by unlocking speed, scalability and novel insight. Traditionally, identifying new drug targets relies on a mix of intuition, laborious experimentation and trial-and-error. Pharmaceutical companies typically take 10 to 15 years to bring a single drug to market, which can cost up to $2 billion. Despite this effort, only about 10% of candidates entering the trial pipeline eventually succeed.

These are concerning statistics, but AI’s ability to sift through vast biological datasets and carry out predictive modelling could be the answer. AI can assist at virtually every stage of the small molecule drug discovery pipeline, including target identification and validation, hit discovery, lead optimisation, and preclinical assessment.

Reshaping structural biology with AI

The use of AI in structural biology has become crucial for modern drug discovery. AlphaFold, developed by DeepMind, represents one of the most groundbreaking achievements of AI. Its creators, Demis Hassabis and John Jumper, were awarded one half of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for protein structure prediction” in recognition of their work on AlphaFold.

Traditionally, tertiary protein structures have been determined through complex and time-consuming techniques such as X-ray crystallography. In contrast, AlphaFold enables the prediction of protein structures based on amino acid sequences, which are readily available in different databases. AlphaFold has been widely adopted by the scientific community and has become an indispensable tool in structural biology since its public release. It enables medicinal chemists and structural biologists to identify binding pockets, model ligand interactions, and perform in silico docking studies, even for proteins previously considered “undruggable” due to lack of structural data.

The recently released AlphaFold 3 model further advances the field by improving the prediction of protein-ligand interactions, including the binding of antibodies to target proteins. This enhanced capability is expected to significantly accelerate the design and optimisation of therapeutic antibodies, which now represent a critical class of biologic drugs.

AI for target identification and drug design

AI plays a pivotal role in both target identification and drug design. Enabling researchers to identify novel or previously overlooked drug targets, AI algorithms can mine genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic data to prioritise genes or proteins implicated in disease pathways. AI also accelerates the discovery of lead compounds by predicting molecular properties and optimising chemical structures.

One of the most promising recent examples of an AI-discovered drug is rentosertib, which is a small-molecule inhibitor of Traf2- and Nck-interacting kinase (TNIK). TNIK was identified as a potential therapeutic target for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) through AI-powered analysis of gene expression datasets profiling the tissue of patients with IPF. A separate AI platform then designed and optimised the small molecule drug. Remarkably, it took less than 30 months to progress from target discovery to the completion of Phase I clinical trials. In a recently conducted Phase 2a trial, preliminary results showed that rentosertib was well tolerated and led to significant improvements in patients’ conditions compared to the placebo group.

Unlocking the hidden potential of existing drugs through AI

AI can also help identify potential medical uses for existing drugs, and this approach can save time by reducing the need to optimise drug structures and address potential safety issues.

Baricitinib is a Janus kinase (JAK1/2) inhibitor originally developed for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. During the COVID-19 outbreak, researchers used an AI-driven knowledge graph platform to explore existing drugs that could potentially be repurposed to combat SARS-CoV-2. Baricitinib was found to have both antiviral and anti-inflammatory properties which could be useful in treating COVID-19, and the FDA approved it for use in patients with severe COVID-19 soon after.

Intellectual Property: The Strategic Imperative

In the rapidly evolving field of AI-driven drug discovery, intellectual property is more important than ever to attract investment and protect your ideas. Securing patents not only protects novel molecules and AI platforms but also increases a company’s value and positions them as a leader in the competitive marketplace of drug discovery.

A 2024 patent landscape report recorded 1,087 global filings related to AI-enabled small-molecule discovery between 2002 and 2024. Recently, patent filings as well as pending applications in this area have surged, reflecting exciting technological progress.

However, unlike patenting new drugs in the traditional pharmaceutical industry, which could be relatively straight-forward, bringing AI into the mix could complicate things.

AI as the inventor

Despite the growing role of AI in research and development, both the European Patent Office (EPO) and UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) clearly stipulate that AI cannot be named as an inventor on a patent application. In the landmark DABUS cases, where Dr. Stephen Thaler attempted to name AI system, DABUS, as the sole inventor, both jurisdictions rejected the applications on the grounds that only a natural person can be legally named as an inventor. Although AI-generated inventions may still be patentable if a human (such as the deviser of an AI model) claims inventorship, AI itself cannot hold legal rights or be recognised as the originator of a patentable invention.

AI-generated inventions

Inventions such as drug molecules and antibodies designed and/or optimised by AI are patentable under UK and EPO law, provided that they meet the standard legal criteria of novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability. Furthermore, experimental data showing that the AI-designed drugs can achieve specific “technical effects”, such as enhanced efficacy, specificity or binding affinity, is key to securing the grant of a patent.

As with any invention, companies should file early to secure protection, as well as conduct thorough IP searches to avoid infringing on others’ rights. Monitoring existing patent filings in biomarkers and therapeutic targets also allows companies to focus their R&D efforts on drug candidates that can satisfy the patentability requirements of novelty and inventive step.

AI as the invention

In addition, it is advisable to consider obtaining patent protection for any novel AI system which identifies biological targets or designs molecules, not just the output.

Along the same line as algorithms and software, intellectual property law in the UK and Europe views AI models per se as of an abstract mathematical nature and therefore not patentable. However, an AI or machine learning invention may be patentable if it produces a technical effect that serves a technical purpose, either by its application to a field of technology or by being adapted to a specific technical implementation.

In this regard, under EPO practice, AI inventions applied to the specific field of drug discovery may be patentable, especially if such AI models solve clearly defined drug development problems (e.g. improving binding affinity or reducing toxicity). Patent protection may also be available for so-called core AI inventions relying on developments of the fundamental underlying AI techniques, rather than application of an AI model to a particular technical field such as drug discovery. The UK follows a broadly similar approach, with courts applying the Aerotel/Macrossan test, originally devised in the context of general computer-implemented inventions, to assess whether an AI invention is a patentable technical contribution.

Thus, while AI cannot be named as an inventor on a patent application, it can certainly be the subject of patent protection if it contributes to the technical character of an invention. Care must, however, be taken in drafting any patent application directed to such AI inventions.

Conclusion

As AI transforms how we discover and design new medicines, intellectual property becomes a critical pillar for translating technological breakthroughs into lasting competitive advantage.

Given the fast-moving nature of the field, a robust, multi-faceted IP approach is crucial. Other things to consider are leveraging trade secrets as well as patent protection and engaging in strategic licensing, open innovation and partnerships to help ease costs, allow broader access to vital data for AI training, and accelerate development. Most importantly, integrating a comprehensive IP strategy into your research and business activities from the outset will position your company to thrive in this dynamic landscape.

Mathys & Squire have published a report on the use of the Unitary Patent system in the field of IT & engineering, sharing the results of a survey on the patents granted to a selected number of applicants in 2023 and 2024 across six technical areas. The report was compiled by Partner Nicholas Fox and Associate Maxwell Haughey.

The Unitary Patent system came into effect on 1 June 2023. Prior to that date, whenever a European Patent was granted, the European Patent automatically became a bundle of national rights for each of the countries designated in the patent. Such national rights need to be maintained separately. In contrast, a Unitary Patent is a unitary right which provides patent protection across all the member states participating in the Unitary Patent system.

Previously, Mathys & Squire sampled a range of applicants in the healthcare sector and investigated their engagement with the Unitary Patent system (view our report here). The analysis revealed that, contrary to popular belief, there was no blanket approach by healthcare companies to engagement with the Unitary Patent system. Rather, widely diverging approaches between different applicants was observed, ranging from almost universal engagement to widespread avoidance.

On the other hand, concerns which may cause diverging approaches to the Unitary Patent system in the healthcare and life sciences field will be different to concerns which applicants in the field of IT & engineering will have.

Applicants in the IT and telecoms field

In contrast to the life sciences where relatively few, but highly valuable, patents are granted, the number of patents in the electronics fields is much larger. Applicants in the IT and telecoms fields consistently appear at the top of the European Patent Office’s list of most frequent filers. However, unlike the life sciences, where patents are normally validated and maintained in a large number of countries, most electronics patents are only ever maintained in the UK, Germany and France. This is more cost effective as due to the London Agreement, applicants do not need to translate their patent into a national language for the patent to have effect in those countries.

For such applicants, engaging with the Unitary Patent system involves a cost, as a full translation of the patent is required. When applicants are obtaining upwards of 1000 granted patents a year, the costs of such translations (typically around €5,000 per patent) will mount up.

Therefore, continuing with the existing approach of only validating patents in the UK, Germany and France, where protection can be obtained without incurring the translation fees, remains attractive.

Applicants in the engineering field

Compared with IT and telecoms, engineering is a half-way house. The volume of patents in the mechanical and engineering sectors is far lower than in the IT and telecoms fields. However, engineering patents are normally maintained more broadly than IT and telecoms patents – typically in around 4-6 jurisdictions (often the UK, Germany and France, and in addition 2-3 other major jurisdictions often selected from Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands). As such, engineering patents very much hit the sweet spot for using the Unitary Patent system. Where patents have traditionally been maintained more broadly, the Unitary Patent system potentially provides the means for patentees to obtain broad geographical coverage at a lower cost than was possible in the past.

In addition, although Unitary Patents are always subject to the jurisdiction of the Unified Patent Court, and as unitary rights they are always subject to the threat of central invalidation, relatively few IT and engineering patents are ever involved in litigation or are the subject of EPO oppositions compared with the life sciences. Opposition rates rarely exceed 3% and for many of these areas of technology opposition rates of less than 1% are common.

Therefore, the Unitary Patent system potentially provides many upsides for engineering applicants with relatively low levels of risk.

Our report on the Unitary Patent system

Whilst the above theorises their approach, the report reveals how applicants in the IT & engineering fields are engaging with the Unitary Patent system in reality. Mathys & Squire’s survey analyses the number of Unitary Patents granted in 2023 and 2024, across six technical areas: digital communication, semiconductors and microchips, civil engineering, transport, defence, and electrical machinery, apparatus and energy. A range of applicants in each area was also sampled to assess the activity of specific applicants.

In summary, the report shows that approaches to the Unitary Patent system vary significantly. However, in general, the percentages of Unitary Patents observed in all IT and engineering fields were lower than the four healthcare fields covered in our previous report, apart from civil engineering, which is perhaps contrary to expectation.

In addition, the percentage of granted IT & engineering Unitary Patents was higher in 2024 than 2023 across all technical fields, which is unsurprising as Unitary Patents were not available for the first five months of 2023. Although applicants had the option of delaying the grant of patents issued in the first half of 2023 until Unitary Patents became available, it seems that relatively few applicants took advantage of this.

Explore the full Use of the Unitary Patent System in IT & Engineering report to uncover changing trends, specific sector insights and the approach of top filers in the industry.

The highly anticipated trial between Getty Images and Stability AI concluded on June 30, 2025. The case has gained national attention, as it represents a pivotal moment for the future of AI and copyright law in the UK.

On 16 January 2023, Getty Images brought proceedings against Stability AI, alleging that the AI company infringed Getty’s copyright by using millions of Getty’s images to train its generative AI model, Stable Diffusion, and that the outputs produced by the model reproduce substantial parts of these works.

The trial, which began on 9 June 2025, has attracted attention from both the technology and legal sectors, as it raises fundamental questions about how existing intellectual property laws should apply in view of modern generative AI systems.

In this article, Technical Assistant Egheosa Ogbomo and Partner Andrew White analyse the proceedings to date and the potential implications of any future developments.

Who are Stability AI and what is Stable Diffusion?

Stability AI is a UK-based artificial intelligence company which develops the family of Stable Diffusion AI models, open-source image generation tools capable of creating or altering images based on text or image prompts. Stability AI trained the original Stable Diffusion model on a subset of a dataset containing billions of images scraped from the internet.

Claims made by Getty

Copyright infringement claims

Getty alleges that Stability AI committed primary copyright infringement by reproducing substantial parts of millions of its images during Stable Diffusion’s training. This involved downloading, storing and augmenting them. They further claim infringement by making Stable Diffusion publicly available in the UK via Dream Studio and other open-source platforms, thus communicating significant parts of Getty’s works.

Getty alleges secondary infringement by authorising users to reproduce or communicate its works when outputs closely resemble Getty images. Secondary infringement due to the distribution of the trained model (an alleged infringing article) in the UK is another claim.

Trade mark infringement and passing off

In addition, Getty claims infringement of its trade marks, asserting that Stability AI used Getty’s marks without consent when generated outputs include Getty watermarks, causing confusion and exploitation of its reputation. They also allege passing off, arguing that generated images containing Getty logos misrepresent them as Getty-owned or licensed, implying endorsement.

Defences brought by Stability AI

Copyright infringement

Stability AI argues that any copying during data sourcing and training occurred entirely outside the UK, as they stored the datasets abroad. According to them, no infringing work was done in the UK. They claim output-stage infringements are the fault of users, since users control the input prompts and, in the case of image-prompts, the degree of input transformation.

Furthermore, they argue that any reproduced portions of Getty’s works are so minimal that they do not constitute a substantial part of copyrighted works and maintain that Stable Diffusion is not an infringing article. They may also rely on the pastiche defence, asserting that the extent of use of Getty’s work was necessary for pastiche, stating that this use does not affect the market for any originals.

Trade mark infringement and passing off

Stability AI claims that outputs containing Getty trade marks were only created through deliberate efforts by Getty’s legal team and do not reflect its normal commercial use. Furthermore, Stability AI denies any likelihood of confusion or unfair advantage. For passing off, it argues any misrepresentation arises from user actions and that outputs are not sufficiently similar to Getty’s works to mislead the public.

Key case developments so far

Since the trial began, Getty Images have dropped their claims for primary copyright infringement, citing a lack of evidence and knowledgeable witnesses to support the allegations. They also dropped their claims over the model’s training and development, maintaining that infringing acts occurred but that there were no witnesses from Stability AI who could provide clear and comprehensive evidence about the entire training process.

For the claims concerning AI-generated outputs, Getty stated that Stability AI has implemented measures preventing the reproduction of infringing outputs. Getty has been unable to establish that any outputs produced by the models reflect a substantial part of its protected images.

This illustrates the difficulty in proving exactly where the training of an ML model takes place for the purposes of determining infringement, as well as demonstrating that AI-generated images reproduce a ‘substantial part’ of protected original works. While this has narrowed the scope of the dispute, Getty’s claims of secondary infringement and trade mark misuse remain in contention.

What are the implications for IP law?

There remains significant uncertainty over the balance of power between AI developers and content creators on copyright licensing. A win for Stability AI in these proceedings could reduce the incentive for AI developers to seek licences in the UK and may lead some to continue developing models without securing permissions, or to do so outside of the UK. This has prompted questions about whether legislative reforms are needed to address potential gaps in protection. However, extending UK copyright law to cover acts abroad could create conflicts with foreign regimes such as US fair use, risking the UK’s attractiveness for AI research and model development.

There has already been a significant increase in the number of AI-related patent applications globally, with the European Patent Office observing a 45-fold increase in the annual number of AI-related European patent filings since 2015. How UK courts interpret copyright law for AI training and outputs could influence the approach to patent applications for AI-related inventions in the UK. Uncertainty over data use rights may consequently affect the development, disclosure and protection strategies for new AI technologies. Companies already face rising costs of data collection, particularly as new technologies such as Cloudflare’s tool will allow website owners to charge fees for access by web-scraping tools.

A final judgement on the remaining claims is likely to be handed down in the next few months. This will set an eagerly awaited precedent for how UK infringement laws should be interpreted in the age of AI, and large-scale text and data mining.

If you have any questions as to how the outcome of these proceedings may impact your IP strategy, please reach out to your usual contact at Mathys & Squire, or get in touch through a general enquiry and we would be happy to help.

Mathys & Squire Partner Michael Stott was recently featured in ‘EPO appeal board establishes ‘on-sale bar’ with big implications for patent owners’ by IAM Magazine. He provided commentary on the ruling on G1/23, issued by the EPO’s Enlarged Board of Appeal on the 2nd of July.

The ruling concerns the interpretation of prior art, determining in particular when a complex product put on the market should be considered part of the state of art and the extent of “reproducibility” which entails prior art status. Previously following a narrow definition of the “reproducibility requirement” established in the EBA’s G1/92 ruling, the EBA lays down in G1/23 that “a product put on the market before the date of filing of a European patent cannot be excluded from the state of the art […] for the sole reason that its composition or internal structure could not be analysed or reproduced by the skilled person.”

The article in IAM highlights how this new decision will have significant ramifications for the patentability of products across a wide range of technological fields, affecting how innovators approach their IP strategy, including when to file patent applications and the use of trade secrets.

To read the full article click here.

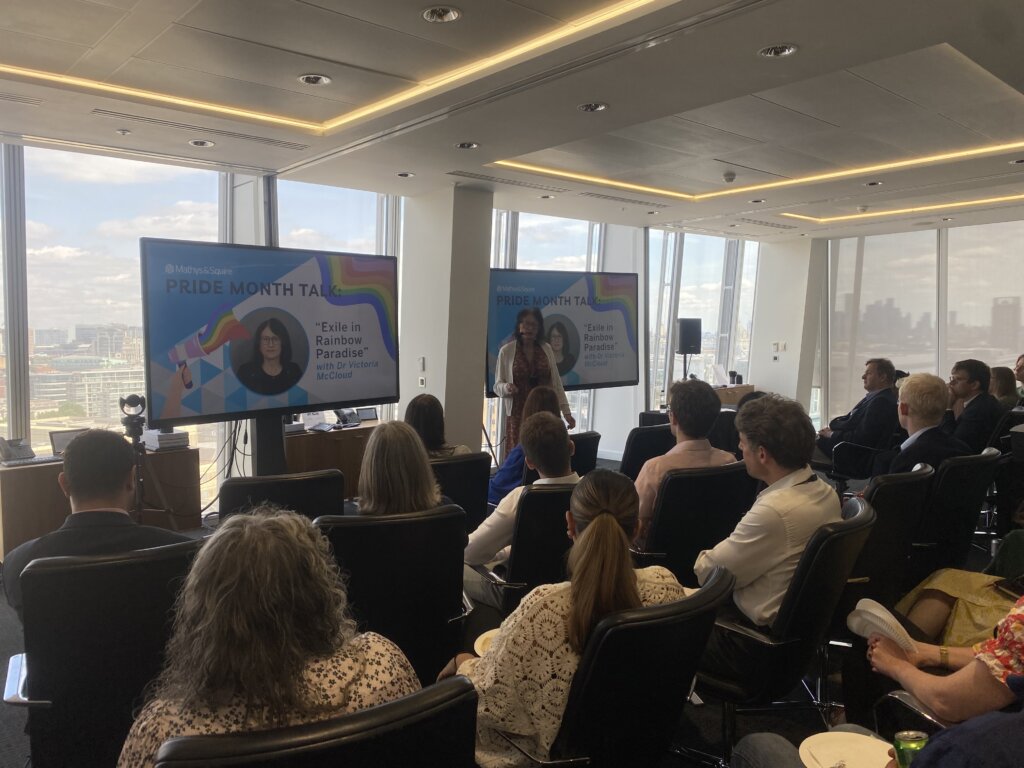

On Wednesday the 25th of June 2025, Mathys & Squire hosted Dr Victoria McCloud, former Judge in the High Court and advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights, in our London office in honour of Pride Month.

From a young age, Victoria discovered a fascination with computers, as well as an acute awareness of human behaviour and interactions – experiencing life through the eyes of a girl as a registered boy at birth. These interests motivated her to pursue a degree in Experimental Psychology and a doctorate in the computational aspects of human vision.

After graduating, she practiced as a barrister, when she came out as a transgender woman, and then went on to be the youngest and first (and only) transgender Master in the UK High Court of Justice.

In 2024, she resigned as a Judge, feeling that there was no longer a place for her as a trans person in the UK court. Now, Victoria McCloud is a freelance public speaker, author and media commentator, raising awareness for issues affecting the LGBTQIA+ community and speaking directly from her experience as a trans woman.

Last year, she featured on the Dow Jones News “Pride of Finance”, whilst this year she reached first place in the Independent Newspaper Pride List and featured in Attitude Magazine’s 101 LGBTQ+ trailblazers 2025.

Victoria gave an educational and engaging talk which followed the timeline of her life whilst delving in to important topics, such as the nature of the UK legal system, changing attitudes towards gender, and her recent move to the “rainbow paradise” of Ireland. She also discussed the topical issue of how the rights of transgender and gay people are under threat in light of the recent Supreme Court Ruling. It was enlightening to gain an insight from someone with a deep understanding of both the law and the trans experience.