For small companies in the medtech space, the most usual exit is to be acquired by a larger corporation. Having seen this process from both sides, through advising a vast number of startups and multi-nationals, I cannot overemphasize how important spending a small amount of time in order to look ahead and get the intellectual property (IP) strategy right at the outset can make a big difference both to the likelihood of a successful acquisition and the sale price.

Following are some top tips on what medtech businesses should do in order to help protect their IP and avoid risks to their inventions.

Think about IP from the outset and start protecting it early on.

If you are successful with your product, potential larger acquirers will want to know:

(a) is it protected, or can it be copied; and

(b) is it free to use or does it infringe someone?

You cannot patent an invention once it has been disclosed publicly, whether in a press release or to potential investors unless those investors are under a non-disclosure agreement (NDA). You should be aware even of teasers which may not go into full detail but make it public enough to render a later patent application obvious. Therefore, it is important that you apply for patent protection prior to disclosing the technical details of your technology. Be wary of including too much speculative information early on as you may reduce the chances of protecting future advances, which could be considered obvious if you hint towards them in earlier applications.

Check that you can show you own the IP.

This is particularly important when you have research and development collaborations or where tech comes from university research/work with healthcare providers. The default in the UK is that the right to patents or designs is owned by the employer of the inventor(s) or designer(s), although this can be altered by agreement. Make sure it is clear from the outset who will own the IP from any collaborations and ensure this is clearly reflected in the IP clauses in the agreement.

Some universities have standard procedures for transferring or licensing the IP, whilst it is harder at others. Ensure you know the terms of your contract and your options before entering into any discussions about who owns the IP and how to transfer it out, if necessary.

Know what IP your competitors have and make a plan for dealing with it.

Third-party IP rights can block you from getting your product to market, lead to potentially lengthy and uncertain litigation, costly settlements or simply make you less attractive to investors. There is a delicate balance as an almost limitless amount of money could be spent searching for and analysing third parties’ IP, whereas doing nothing may result in being surprised by something that really should have been identified before and may have been a simple work-around or might have been effectively neutralised, had it been identified earlier.

Consider third-party observations or oppositions (in Europe) which are much cheaper than litigation or Inter Partes Review (in the US) to help prevent competitors getting IP that may be an issue. Gaining protection which may interfere with competitors’ commercial activities, even if such IP does not directly cover your own, may improve your negotiating position and provide a disincentive for competitors to assert their own IP against you.

Tie in your IP strategy closely to your funding and business plan.

It is not essential to apply for worldwide protection for everything from day one. Work out what you need to protect early on – the key concept is anything you have to disclose publicly to obtain funding – and file a national application with little or no official fees. Defer costs by filing an International PCT application a year later, which puts off the decision on which countries you eventually want to pursue protection in for two and a half years after the initial filing. Include several concepts in one application; you are likely to get an objection that the application relates to multiple inventions but can file divisional or continuation applications later to protect separate concepts, reducing the initial cost of official fees and prosecution.

It is normally quicker and easier to obtain protection for narrower concepts, so if there is a difficult battle and funds are tight, one strategy is to focus on getting something useful protected early on, while ensuring you have basis to protect the broader idea in a divisional or continuation later when you hopefully have more funding. Investors often want to know you have registered IP and showing a few early grants for patents that read directly onto your products can be very helpful.

Aim to achieve good protection in key territories rather than weaker protection everywhere.

Think about the key markets for yourself and your competitors; where your competitors are based and manufacture; and where – normally as a last resort – you would litigate if needed. It would be very unusual to fight litigation in every possible market. The US, Europe – particularly Germany and the UK – and, increasingly China, are normally key territories. But this very much depends on the marketplace and your commercial strategy.

Beware that IP protection differs throughout the world. For example, there are restrictions on patenting medical methods of treatment or diagnosis in Europe. Although, the devices can be protected as can related methods, as long as they do not involve the actual treatment or diagnosis. Taking a strategic view early on may give you better outcomes.

Don’t overlook registered designs and trade mark protection.

Registered designs are relatively cheap; a few hundred to a few thousand pounds, and fairly quick; a few weeks to a few months to obtain as they do not require substantive examination prior to grant. Designs cover products which are novel in appearance (i.e. design), rather than technical innovations.

If you have spent time and money getting your product to look right, whether a web/app interface or a hand-held device, then it is normally worthwhile to obtain registered design protection. If you are successful, your brand may become your biggest asset so set your brand strategy early and don’t do things to weaken it.

Finally – a little good strategic advice early is generally much cheaper and more valuable than scrabbling to resolve problems after they have become serious enough to get your attention.

This article was first published in Medtech Insight in May 2019.

In an episode of CUTalks, Mathys & Squire Partners James Pitchford and Craig Titmus speak to Cambridge University Technology and Enterprise Club (CUTEC) hosts about the secrets of good IP management for founders and business owners.

The podcast covers a range of IP management topics, including types of IP; advice about timing; costs associated with IP for international reach; and examples of tech-based scenarios with IP advice.

To listen to the full podcast, please click here.

On 27th March 2019, the IP Tribunal of the Chinese Supreme People’s Court (the CSPC IP Tribunal) handed down its first judgment of an appeal case since its establishment on 1st January 2019: Xiamen Lucas Auto Parts Co., Ltd. (China, hereinafter “Lucas”), Xiamen FuKe Auto Parts Co. Ltd. (China, hereinafter “FuKe”) v. Valeo Systèmes d’Essuyage (France, hereinafter “Valeo”).

Summary

The CSPC IP tribunal, in its very first judgment, explored the relationship between interim judgment and temporary injunction when they coexisted in a trial. The CSPC judges also discussed claim construction and gave guidelines on the criteria on assessing functional and “means-plus-function” features in its role as a national appeal court.

Background

Valeo is a French supplier of car wipers and sued Lucas, FuKe and Chen Shaoqiang to the Shanghai IP Court for infringing its Chinese patent ZL200610160549.2 (Wiper connector of motor vehicle and the corresponding connecting device) by manufacturing and selling three models of car wipers. The Shanghai IP Court acknowledged the infringement and issued an interim judgment on 22nd January 2019, ordering Lucas and FuKe to immediately stop infringing Valeo’s patent rights. Then Lucas and FuKe filed an appeal to the new CSPC IP tribunal.

The appeal

The CSPC IP tribunal accepted the appeal case on 15th February 2019 and held the public hearing on 27th March 2019. The panel of five judges maintained the interim judgment of the Shanghai IP Court and the judgment was pronounced in court.

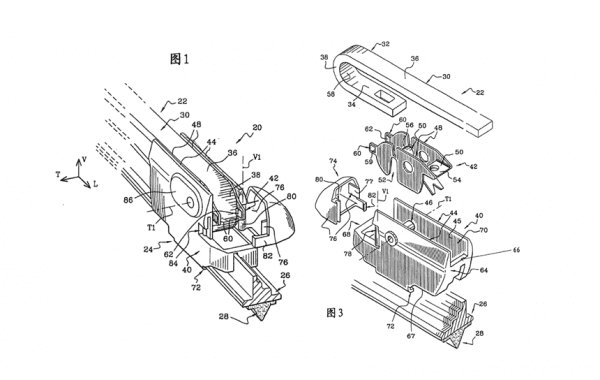

Fig.1 and Fig.3 of Valeo’s Chinese patent ZL200610160549.2

Claim construction

The first core issue discussed in court was whether the alleged infringing products would fall within the scope of claim 1 of Valeo’s patent. In particular, three technical features of claim 1 were analysed by the CSPC judges:

1) Claim 1 recites “a connector (42) of a wiper for securing a connection and articulation between a wiper arm (22) and a component (40) of a wiper blade (24)” (feature 1). Lucas and FuKe claimed that the wiper arm and a component of wiper blade of the alleged infringing products were not directly connected and articulated as recited in claim 1. The CSPC judges disagreed with them and stated that claims and terminologies should be interpreted, from a skilled person’s point of view, based on claims in combination with the description and drawings and cannot be interpreted in isolation, because according to Article 59 of Patent Law of the People’s Republic of China “For the patent right of an invention or a utility model, the scope of protection shall be confined to what is claimed, and the written description and the drawings attached may be used to explain what is claimed”. Firstly, feature 1 itself didn’t exclude indirect connection of the wiper arm and wiper blade, and secondly, paragraphs [0043] and [0044] of the specification and Figs. 1 and 3 show that the wiper arm and the connector were connected, and the connector and a component of the wiper blade were articulated, therefore the connector secured the connection and articulation of the wiper arm and a component of the wiper blade, which means that skilled person would understand that feature 1 didn’t require direct contact of the wiper arm and a component of a wiper blade. Therefore, feature 1 could read onto the alleged infringing products.

2) Whether the alleged infringing products include feature 2 “at least one elastically deformable member (60) – the member (60) locking the connector (42) at an embedded position at the front end (32) of the wiper arm (22)”. Lucas and FuKe argued that the elastic member of the alleged infringing products can only “fix” rather than “lock” the connector. Again, the judges restated that the skilled person reading the original disclosure (the description, claims and drawings), would understand that “locking” in claim 1 does not mean tight “locking” but only “fixing” or “locking to a certain extent” in the context that Valeo’s patent aimed to address a technical problem of accidental disengagement of the connector. The three alleged infringing products all comprise elastic members which are configured to fix the connector or lock the connector to a certain extent at an embedded position at the front end of the wiper arm. Feature 2 thus could also read onto the alleged infringing products.

3) Whether feature 3 “in the closed position, the safety fastener (74) extends toward the locking member (60) for preventing elastic deformation of the locking member (60) and locking the connector (42)” was a “”means-plus-function” feature or not. The CSPC judges overruled the Shanghai IP court’s interpretation of feature 3 as a means-plus-function feature and investigated the boundary of identifying a functional feature. According to Articles 8 of CSPC’s Interpretation (II) of Several Issues concerning the Application of Law in the Patent Infringement Dispute Cases, that if a certain technical feature has defined or implied specific structures, components, steps, conditions or the relationships of a technical solution, even if the technical feature also defines its function or effect, in principle it is not a means-plus-function feature.

In the present case, the judges clarified that feature 3 described the position relationship between the safety fastener and the locking member and also implied a special structure – “the safety fastener extends toward the locking member”. Therefore, feature 3 further contributed position and structural limitations (also seen at paragraphs [0056] of the description) and thus is not to be interpreted as a means-plus-function feature, and its positional, structural and functional limitations should all be considered when the features are compared for infringement analysis.

The judges then found that three models of car wipers had equivalent positional/structural/functional features as feature 3, and again feature 3 could also read onto the alleged infringing car wipers.

In conclusion, the three alleged infringing products therefore fell within the scope of claims 1 of Valeo’s patent.

The interim judgment and the temporary injunction

The second core issue was how to deal with the temporary injunction request in the second instance.

In the first instance, Valeo requested a temporary injunction to stop the defendants from continuing alleged infringing activities. However, the appeal was filed shortly after Shanghai IP Court issued the interim judgment, leaving the temporary injunction request undealt with.

In the second instance, the temporary injunction request was transferred to the CSPC IP tribunal. When dealing with the temporary injunction request in light of the first-instance interim judgment, the CSPC judges applied a special test to see if there would be any urgent damage made to Valeo and if yes, whether the CSPC IP tribunal would be able to make a final decision when the temporary injunction was being processed. In this case, the evidence submitted by Valeo was not sufficient to approve the urgency of damage, and in view of the fact that the judgment was pronounced in court, Valeo’s temporary injunction request was therefore not supported by the CSPC IP tribunal.

An “Innovative” hearing

The CSPC IP tribunal’s first public hearing emphasises the concept of “protecting innovations in an innovative way”:

1) As mentioned at the beginning of this article, this is the first judgment of the CSPC IP tribunal, which was established to handle appeals decided by Chinese Intermediate People’s courts or IP Courts in invention patent cases as well as other highly technical IP cases. Such a national appeal court will unify the criteria of IP trials, help prevent inconsistency of legal application and improve the quality and efficiency of trials.

2) The CSPC IP tribunal, for the first time, explores the relationship between the interim judgment system and the temporary injunction system, and clarifies the conditions when the two systems coexist.

3) The CSPC IP tribunal closed the whole case within an impressive 50 days, from case acceptance to decision delivery. The speedy second-instance decision enabled Shanghai IP court, which made the interim judgment to simplify a complicated first-instance trial, to continue the rest of the trial in good time.

4) The judgment of the CSPC IP tribunal explained in detail the rules for identifying a functional feature and a means-plus-function feature, which is particularly relevant because means-plus-function features are typically interpreted quite narrowly. This decision, encouragingly, interprets the feature of the locking member in a manner such that it is not restrictively interpreted as a means-plus-function feature, perhaps opening the way to more functional claim language being interpreted in such a way in China.

5) Various different forms of technical support were used during the hearing. For example, Augmented Reality (AR) technology was used to display evidence, speech recognition was used to generate transcripts, and a QR code was provided for downloading the decision.

Continuing…

On 23rd, April 2019, the CSPC IP tribunal’s held a public hearing of the first administrative case: appellant Baidu, Inc., Sogou, Inc. and the appellee State Intellectual Property Office Patent Re-examination Board. Due to the complexity of the case, the court did not pronounce a judgment in court. However, we will continue to watch this case and future decisions made by the CSPC IP tribunal.

Mathys & Squire and Food Tech Matters will be co-hosting a VIP pre-launch party to Food Tech Matters 2019.

Food Tech Matters is a meet-up between the best food tech startups from all over the globe, corporates, accelerators and leading food tech investors who attend not only to hear about the latest food tech trends and developments from the experts, but to forge strategic partnerships to accelerate these breakthrough technologies. The event will be held from 25th – 26th June 2019 at The Crystal, London.

As the official IP partner, Mathys & Squire will co-host the VIP pre-launch party at our London office in The Shard. Below are the details:

When: Tuesday, June 18th 2019

Time: 18:00 – 21:00

Where: Mathys & Squire, The Shard, 32 London Bridge Street, SE1 9SG

*Please remember to bring photo ID to enter The Shard

If you’re interested in attending the event, please email the Mathys & Squire Marketing Team by Friday, June 14th 2019.

Mathys & Squire will be at this year’s INTA annual meeting in Boston, from 18th – 22nd May. Our team will be available to discuss all things trade marks, patents and designs, as well as IP strategy and valuation. Please feel free to contact them through their profiles to schedule a meeting.

The INTA Annual Meeting is the largest and most influential gathering of brand owners and intellectual property (IP) professionals from around the world and from across industries. The 141st Annual Meeting in Boston, Massachusetts, will leave you with critical insights, best practices, and knowledge about new market trends to drive your organization forward—as well as with vital connections that will enhance your professional and personal life.

Our INTA team comprising of Gary Johnston, Margaret Arnott, Rebecca Tew and Laura West will be present and are excited to meet new faces.

Please feel free to contact our marketing team on [email protected] if you require more information.

Mathys & Squire and RSM are pleased to be co-hosting ‘An introduction to AI’ during London Tech Week. The event will be held on Monday, June 10th 2019 at 25 Farringdon Street, London, EC4A 4AB.

We will be providing an overview on artificial intelligence (AI) and how it is and will continue to change business operations across a range of functions and industries; what are the challenges when it comes to implementing and utilising AI; as well as the opportunities that can arise in this brave new world.

Schedule

4pm: Registration

4.30pm: Welcome from David Blacher, Head of Media & Technology at RSM

4.35pm: Introduction to AI presented by Neil Sharples, Partner at RSM

5.05pm: IP in relation to AI – challenges and opportunities (presented by Andrew White, Managing Associate at Mathys & Squire)

5.30pm: Drinks and canapés

To register for the event, please RSVP to Saba Ismail.

We talk to Phil Staunton, Managing Director of D2M Innovation Ltd, a design consultancy that helps turn great ideas into brilliant newly manufactured products that sell.

Manufacturing is the stage at which a product finally comes to life and, after many months or even years of planning, designing and re-designing, this is an exciting time in the journey from concept to market. That said, it can also be a daunting stage and one in which speed to market remains key.

Phil Staunton, who founded D2M Innovation in 2010, has over 10 years’ experience of supporting start-up businesses and SMEs develop and launch innovative, new products onto the market. He now specialises in strategic planning of product development to minimise risk and therefore maximise the chances of success.

Phil explains that there are up to 18 main stages of work you are likely to progress through, and his advice is: “Do not compromise on shortcuts that may create bigger issues further down the line. Bear in mind that, often, you will have to choose between quality, cost and time to completion, so make sure you know which are most important to you.

“Make sure that you inform the manufacturer of any particular standards or certification that your product needs to comply with and, ideally, select a manufacturer that is used to working to the standards of the countries where you plan to sell your product.

“The right manufacturing partner is the key to the success of your product, and before you embark on the process of selecting your manufacturer, you will need to have a manufacturing specification for your product, which is a complete representation of the product which provides any suitable manufacturer with the right information for production.”

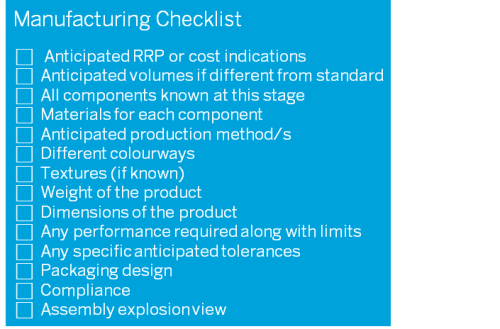

Phil recommends using a checklist, like the one below, to make sure you don’t miss anything important.

Another thing worth considering before the manufacturing specification is completed, is whether or not to consider registered design protection for the product in its final form. This can provide powerful protection for the appearance of your product, and unlike patents, can be put in place quite quickly to guard against copies of your product entering the market very shortly after yours. Not only can this severely affect your own sales, but if the copies are of poor quality your brand can also be badly damaged.

Ultimately, though, Phil adds: “You are not the first entrepreneur following this path. You will probably make mistakes during this process. Learn from these, be reactive, and don’t give up!”

This article was first published in Business & Innovation Magazine in May 2019.

One of the most common issues faced when securing protection in China is the earlier registration of third-party rights, which are then cited against the later application. However, there are various tactics that can be adopted to overcome this hurdle.

Many articles are written about various aspects of the trade mark system in China: the risks of the first-to-file system, the development of the law in recent years, the behaviour of trade mark squatters and the production of counterfeit goods. However, fewer focus on the obstacles encountered when filing in China or offer practical guidance on how to overcome or address these.

For foreign businesses attempting to protect their marks in China, objections throughout the prosecution process are reasonably commonplace for various reasons, including significant differences between China’s legal system and those of other countries. However, in our experience, one of the most common issues is the earlier registration of third-party rights that are then cited against the later application and form a block to its progress. Under the Chinese system, the onus is on the applicant to overcome the possibility of confusion with earlier rights, as compared to it being up to the earlier rights holder to actively object to a later application.

Having assisted many clients over the years that face this exact problem, we have had to consider and develop

several potential strategies and solutions for tackling the issue. Below are a handful of the methods we regularly

use to try to obtain protection.

Pre-filing

Anyone filing in China should be aware that the classification system is unique and that a specification drafted for elsewhere in the world is unlikely to pass the Chinese examination process without some form

of query or objection being raised. Where possible, it is therefore advisable to obtain a full list of the terms included within each relevant sub-class from a Chinese attorney and to consider creating a separate or adapted specification for use in China that either utilises those terms in place of the specification employed in the jurisdiction where the mark was first registered or lists them alongside, to assist with later adaptations.

This will not always be possible (e.g. if filing via the Madrid Protocol or where a priority claim means that a previously drafted specification must be used). However, in instances where the strategy may be employed, it is advisable to consider doing so.

It will be useful from a wider prosecution perspective but can also help to avoid the unnecessary citation of earlier rights. For example, it can often be the inclusion of one term in one sub-class that prompts a citation from the China Trademark Office (CTMO). When, for example, a UK specification has been used, this may be an unnecessarily wide-reaching term that could have been removed or limited prior to examination in order to avoid the citation.

Conduct Searches as Soon as Possible

Pre-empt Objections

Despite the propaganda, the trade mark system in China no longer lives up to its Wild West reputation; there is a wider acknowledgement of the value of intellectual property and the authorities are adapting the law in an attempt to stamp out the dishonest practices that gave rise to the reputation in the first place. However, trade mark squatting is still present and there will always be individuals and businesses that see the financial opportunity presented by the first-tofile system.

For this reason, you will often find that a client’s brand is illegitimately registered in China even before that client has decided to protect the mark itself.

Because of this, as well as the potential existence of legitimately registered earlier rights, it is strongly advisable to conduct searches as soon as there is any indication that the client has an interest in the Chinese

market. Where no obstacles are found, early filing is also strongly recommended to prevent interim disruptive filings by third parties.

Searches and Non-use Actions

One of the most common methods of overcoming the citation of an earlier right is to file a cancellation action against the earlier right on the basis of non-use (i.e. where it has been registered for more than three years and no obvious use can be identified). This is a useful way of removing the citation from the register and thus clearing the way for the client’s application.

However, the process is not always straightforward; if the non-use action has been prompted by an official objection to a trade mark application, the CTMO will not generally agree to suspend examination of the application pending the outcome of the non-use action, thereby leaving the client with no option but to file the non-use action, abandon the application and re-file in the hope that by the time the new application is examined, the non-use action is close to being concluded.

This is why pre-filing searches are so important in China; it is much more beneficial to know about potential citations in advance of filing so that you can instigate those actions early, rather than wait 18 months until you receive a refusal and then potentially have to start from scratch. Indeed, in circumstances where nonuse actions are instigated before either the filing or the provisional refusal is issued, the CTMO is more likely to agree to a suspension pending the outcome of the cancellation action.

Thus, discovering potential citations before filing could lead to the development of a more informed strategy that reduces the time and cost involved in obtaining protection.

Invalidate Earlier Registrations

Where a non-use action is not possible (either because the registration is too young or use is being made in China), clients can also look at pursuing an invalidation action against the cited right.

These can be based upon a number of grounds, including earlier proprietary rights or bad faith; the latter of which is more likely to succeed when there is evidence of squatting and dishonest intentions.

However, such actions are generally difficult to support in the absence of good evidence, a copyright registration or prior use/protection of the mark in relation to virtually identical goods to those included within the cited registration.

Indeed, a handful of our clients have discovered identical logo marks registered in China in classes in which they have no protection and have not previously used their marks. In these circumstances, invalidation

actions failed despite the logo being clearly identical due to the lack of pertinent evidence of use or ownership in relation to the contentious goods or services.

Wait

Sometimes, despite all one’s best efforts, none of these options are viable and it is difficult to identify a route forward. In these circumstances, the client may need to accept that it has to play the long game. Generally if the application was filed by a squatter, there will be no real intention to use it and so you could choose to diarise the three-year non-use date and then pursue non-use proceedings as soon as possible,

while simultaneously re-filing for the client’s mark in the hope of achieving the above-mentioned stay of proceedings, if necessary.

Consider Copyright Protection

In the interim, or even as a defensive mechanism alongside an initial trade mark filing, copyright registration in China can provide a useful addition to a client’s portfolio and additional armour against trade mark

misuse or misappropriation. Indeed, it provides the client with a registered right protecting its stylised mark and it is not limited by the same classification system.

For clients with distinctive logos, a copyright registration can provide a strong alternative right for enforcement purposes. For example, the client can obtain a registered right to record with Customs, and potentially a broader-reaching right to enforce against squatters filing to protect the client’s logo in different classes of goods or services. It is therefore well worth considering.

Purchase Earlier Rights

It is no secret that trade mark squatters will often request huge sums of money in return for the transfer of an earlier trade mark registration for the client’s brand (or something similar). Often the figure put forward is far in excess of the value of that registration, particularly in view of the fact that squatters rarely take the steps to enforce those rights against the rightful owner.

However, in certain circumstances, the purchase of an earlier right may be worth considering – for example, if the value is reasonable in comparison to the cost of pursuing actions at the CTMO, potentially having to re-file and being forced to stall enforcement action in the interim.

Moreover, this could be an option worth considering where a mark is already within the non-use period or very close to that period and thus more vulnerable, or where there was actually a genuine intent to use but it has fallen out of use, or perhaps if there are overseas rights that can be used as leverage in negotiating a commercial relationship that could benefit both parties.

However, do consider who is best to begin those negotiations, as an initial approach from a lawyer is not always looked upon favourably from a cultural perspective.

This article was first published in the June/July 2019 edition of World Trademark Review.

For more information, contact Margaret Arnott or Laura West.

The food and drink industry is one of Europe’s largest manufacturing sectors, with, according to FoodDrinkEurope, an annual turnover of €1,109bn. However, in order to capitalise on this lucrative industry, manufacturers must follow (or more ideally stimulate) changing consumer demands and government initiatives.

One of the most significant recent consumer trends has been the increased demand for healthier foods and drinks. Consumers have become much more conscious of maintaining a healthy and balanced diet and are looking more critically at the ingredients contained within their food and drink.

In recent years there has also been an increased awareness of the methods of manufacture, the inclusion of additives and the sourcing of food and drink ingredients. The desire to live healthier lifestyles has resulted in, among others, an increased demand for new vegetarian and vegan options, nutritionally improved and ‘gut healthy’ foods.

This change in consumer purchasing is reflected in the given drivers for innovation in the food and drink industry, with health food trends (natural, medical and vegetal) reported as showing the greatest increase in 2017, particularly in the soft drink sector, which was recorded as the most innovative sector in 2017.

No doubt this change in manufacturing drivers is, at least partly, related to the new national guidelines, such as those published by Public Health England (PHE), which aim to reduce the amount of sugar in children’s food by 20% by the year 2020, and the general EU benchmark of reducing added sugars in food products by a minimum of 10% by 2020, with respect to the baseline levels of member states at the end of 2015.

But what if consumers grow tired of this healthy lifestyle trend and want to give in to ‘naughty’ urges once again? Is it possible to maintain a healthier lifestyle and continue to eat the comfort foods that we all know and love? Essentially, is it possible for us to have our cake and (quite literally) eat it too?

Fortunately, many food and drink manufacturers have committed extensive time and resources to looking at this exact issue. In recent years, research and innovation in the food and drink industry has not been solely focused on providing new healthy, micronutrient filled foods for us to try. It has also looked at how to make the food and drink products traditionally associated with higher calories and increased amounts of fat, salt and sugar healthier, while maintaining the texture, taste and appearance we have come to expect and enjoy.

Reduced Fat Fish and Chips

Fish and chips is quintessentially British fare, using a batter formed from a slurry of wheat flour and water. However, deep-fried foods

such as these absorb large amounts of oil during cooking, which significantly increases their calorific content and reduces the nutritional value.

Fortunately, VA Whitley & Co Ltd, a UK supplier to the Fish and Chip and Fast Food Trade, has perfected a healthier batter which comprises fava bean flour (from the Vicia faba bean) in place of the traditional wheat flour. The fava bean flour has been found to reduce fat/oil uptake during cooking, while importantly maintaining the familiar colour, texture and taste of traditional fish batter.

Not only does this batter reduce the overall calorific content of the resulting food product, but it also meets many of the other consumer-driven demands of today. For example, the use of fava bean flour provides additional health benefits over wheat flour as it is higher in protein, fibre, and trace minerals. Fava bean flour is also gluten-free, and so is suitable for those among us who are either intolerant to or just prefer to opt for gluten-free alternatives.

Low Sodium Salted Treats

It is well documented the consumption of excessive amounts of sodium can produce detrimental effects on the circulatory system, such as high blood pressure, as well as kidney affections, water retention, and stomach ulcers.

While many manufacturers have gone some way to meet the PHE salt reduction targets, this has to be balanced with a strong consumer demand for the flavour and organoleptic qualities of salt, particularly sodium chloride.

In order to reduce the amount of salt required in food products, ConAgra Foods Ltd, a US based food manufacturer, found that a solution to this conundrum is to use salt with a mean particle size of less than 20 microns. This invention is based on the fact that reducing the mean particle size of salt increases the total surface area of salt for a given weight. The larger surface area of salt acting on the tongue, provides the same salt perception to the consumer but with the advantage of lower amounts of salt. ConAgra’s proprietary Micron Salt, can be found in its Orville Redenbacher’s popcorn.

Healthy Chocolate

“Chocolate is a perfect food, as wholesome as it is delicious, a beneficent restorer of exhausted power…it is the best friend of those engaged in literary pursuits.” – Justus von Liebig.

While chocolate is a favourite treat for many of us, an increased consumption of sugar has been linked to the higher levels of obesity

in the UK, with the Health Survey for England 2017 finding that 64% of adults were either obese or overweight. Obesity has in turn been linked to diseases such as type 2 diabetes. One food product often discussed with respect to the increase in obesity is milk chocolate, as over half of the weight of a chocolate bar may be due to sugar alone.

IMMD SP Z OO, a company specialising in the field of biotechnology, has dedicated research into finding ways to make chocolate healthier for consumers. Its patent (WO 2018/087305) describes a chocolate product comprising a polyphenol-rich plant extract, preferably trans-resveratrol (t-RSV).

The incorporation of polyphenols in milk chocolate has great health implications as polyphenols have been shown to interfere with glucose absorption in the intestine. IMMD SP Z OO also states that the chocolate containing polyphenols can provide ‘antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-hypoxic, vascular supporting and/or other health benefits’.

Low-Fat Baked Goods

Over the years, bread and bakery products have become a staple in our diets. However, compared to other food types, baked goods can contain higher calories and higher amounts of carbohydrates, along with providing fewer vitamins and minerals.

One particular type of baked product which is known for its higher calorie content is puff pastry. Puff pastry is formed from a dough laminate containing many alternating layers of the basic dough and a fat. Fat plays an integral role in forming the puffed final product.

During baking, the water contained within the dough is turned into steam, which is trapped by the thin layers of gluten, causing the dough to expand. The fat layers contained in the dough act as a barrier, preventing the gluten layers from joining together. In order to function as an effective barrier layer, the fat used must contain certain levels of plasticity (to enable the dough to be rolled and folded when creating the laminate structure) and firmness (as softer fats can be absorbed by the dough).

While it would be desirable to produce puffed pastry products which do not weigh as heavily on the calorific scales, this problem cannot be solved by simply using less fat or substituting the fat for a softer alternative, containing lower trans fats.

However, AAK AB, a company specialising in vegetable oil and fats, has developed a reduced fat bakery emulsion that enables the preparation of low-fat puff pastry. In order to reduce the fat content of the emulsion, while still maintaining the required plasticity and firmness, the patented bakery emulsion replaces part of the fat traditionally used with natural additives, such as maltodextrin, which mimic the properties of the fat.

Reduced Sugar Soft Drinks

As discussed above, national organisations, such as PHE, have heavily publicised targets for reducing the sugar content of a range of products that contribute most to children’s sugar intake by at least 20% by 2020.

One organisation taking this challenge head-on is Lucozade Ribena Suntory (LRS), a European based company owned by Japanese manufacturing company, Suntory, which has announced that it aims to reduce the sugar content of all of its existing and new beverages to less than 4.5g per 100 ml (compared to previous 10 to 11g per 100 ml). LRS has managed to remove a staggering 25,500 tons of sugar and 98 billion calories from the company’s annual drinks production and states that this dramatic change has not affected the taste of the soft drinks produced.

So, how are manufacturers meeting these new government-led and consumer-driven targets?

One main method of lowering sugars in food is to replace at least some of the sugar present with sweeteners. Unfortunately, the incorporation of higher amounts of sweeteners can lead to the presence of an off/bitter taste. It is known that the presence of artificial sweeteners within food products not only stimulates the human sweet taste receptors, but also activates bitter taste receptors (TAS2Rs), causing this unpleasant ‘off-taste’.

In recent years, LRS has been reformulating its drinks products in order to reduce sugar content while maintaining a sweet taste. One method of achieving this is discussed in the patent of Suntory Holdings Ltd, WO 2018/225817, which discloses a sweetening composition comprising a combination of natural sugars, high-intensity sweeteners and low concentrations of sodium. The invention utilises the fact that the perceived sweetness of a food or drink product is increased by the presence of sodium.

Protecting Market Share

Producing food and drink products which meet all of these requirements can provide companies with a competitive advantage, but the question remains: how can this advantage be maintained and how do companies prevent competitors reaping the rewards from their research and investment?

We see numerous examples of food and drink manufacturers maximising the effectiveness of their IP protection as they develop innovative product ranges and tests to meet fast-moving consumer demand. IP protection can relate to the finished food product, a specific combination of ingredients or the manufacturing process itself, as well as working with design law to protect the aesthetics of products, the food product itself and its packaging.

This article was first published in the May 2019 edition of Intellectual Property Magazine.

Patents provide an alternative and interesting source of information for identifying emerging technology trends. One such recently observed trend supports a growing interest in the use of indirect biomarkers in diagnostic assays. This article describes the key differences between direct and indirect biomarkers, and illustrates two examples to show how indirect biomarkers are providing new clinical diagnostic opportunities, namely to improve initial triaging of patients in accident and emergency scenarios and to allow rapid and accurate screening of patients carrying a latent tuberculosis infection.

Classical diagnosis of disease-causing agents relies on identification (i.e. direct detection) of a key biomarker that is characteristic of said agent. Examples of such biomarkers include: nucleic acids (detection via polymerase chain reaction hybridisation, sequencing, isothermal amplification); antibodies (detection via ELISA, immunofluorescence (IF)); antigens/ proteins (detection via ELISA, IF); and agent isolation (detection via differential cell culture means). This, in turn, requires knowledge of the infectious agent in question (table 1), and goes together with constant refinement pressures to ensure all newly-emerging variants are also captured. The high specificity typically demonstrated by such biomarkers, however, unfortunately presents an Achilles’ heel when a negative diagnostic outcome is reached such that further intelligence (other than subtractive analysis of the targeted agent per se) can be gleaned.

It should also be noted that the different biomarker types demonstrate their own strengths and weaknesses when assessed in terms of, for example, minimum diagnosis time requirements, transportability, relevant detection window timeframe, and sensitivity (table 2).

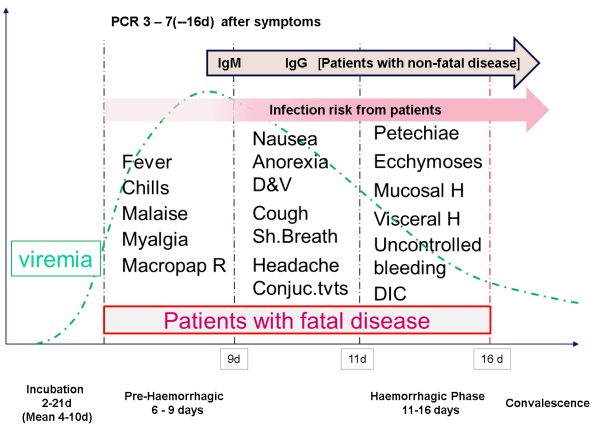

By way of example, the following Ebola case study (figure 1) nicely illustrates the potential criticality of detection window factors that impact both polymerase chain reaction and antibody detection. In more detail, premature use of polymerase chain reaction detection during either the ‘incubation’ or early ‘pre-haemorrhagic’ phases will likely result in a false negative. Similarly, premature use of a diagnostic for IgM up to and including the mid ‘pre-haemorrhagic’ phase would also likely yield a false negative.

Figure 1: Multiple Biomarkers – Ebola case study (source: Prof Nigel Silman, PHE Porton, Salisbury SP4 0JG)

While significant advances have been made with classical biomarker diagnostics, there remains a variety of notable unmet clinical needs:

- rapid, accurate biomarker tests for differential diagnosis;

- biobanks of well characterised clinical

samples;

requisite materials to construct immune-assays and

molecular diagnostics;

true point of care platforms for diagnostic

assays; and

robustness to permit field use.

Is now the time for an alternative (potentially supplementary) approach?

Recent developments with the use of indirect biomarkers (e.g. differential gene expression or metabolism profiles) have attracted significant interest. The use of carefully selected biomarker sets in combination with robust algorithms provide important assay flexibility and allow specificity and/or sensitivity levels to be dialled-up or down as appropriate to achieve an optimal read-out. Moreover, this flexibility provides the means for further interrogation of a clinical scenario where initial diagnosis has failed to identify a positive outcome, and thereby addressing one of the major weaknesses associated with classical biomarkers weaknesses.

By way of example, WO2018/060739 teaches use of a variety of different marker sets can be employed to distinguish between septic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and sepsis, and subsequently to differentiate between important subsets thereof. In more detail, a simple triage diagnostic of this type would find immediate value, for example when assessing a patient who has presented in any emergency scenario. Rapid point of care confirmation that the patient has SIRS would negate the need to administer antibiotics, and potentially represents a huge step forward in improving current antibiotic husbandry.

Similarly, for a patient presenting with sepsis, being able to differentiate between abdominal sepsis and pulmonary sepsis would permit a more informed decision to be made with regard to the type of antibiotic administered (e.g. to target gram positive, or gram negative bacteria). Another interesting biomarker set described allows one to monitor patient recovery and hence to determine more accurately the correct time point for appropriate patient discharge from hospital. This would, of course, help to address current bed capacity problems without compromising patient safety.

By way of further example, WO 2015/170108 teaches use of a variety of biomarker sets for identifying M tuberculosis infection. This infectious cycle of this agent includes an intracellular ‘latency’ phase during which bacilli do not circulate freely within the body, and are therefore particularly difficult to detect. A further setback with the use of classical biomarkers for detecting M tuberculosis is skin testing may be compromised by BCG vaccination and by exposure to environmental mycobacteria. The presence of a large reservoir of asymptomatic individuals latently-infected with mycobacteria presents a major problem for global control of M tuberculosis infections. This is indeed a key priority for many health and immigration authorities, particularly at the ‘point of entry’ for developed countries where the majority of TB cases are imported. The indirect biomarker sets described achieve both accurate and timely diagnosis of early-stage infection where conventional biomarker detection (via cell culture or PCR) is not possible. Possibly of most significant interest, the authors describe use of unique marker sets that provide robust diagnosis of latent M tuberculosis at sensitivity and specificity levels far superior than have been hitherto reported.

These two brief case studies illustrate the huge opportunities indirect biomarkers present for rapid bio-sensing technologies for both the control and prevention of infectious diseases, and related heath- or life-threatening management scenarios.

We urgently need to start moving away from sole reliance on classical biomarkers (noting in particular the impotence of these markers in negative diagnostic output scenarios) and start embracing the new world of indirect biomarkers to detect and characterise important host signature profiles.

This article was first published in the April 2019 edition of Intellectual Property Magazine.