In this article for AgFunderNews, Mathys & Squire partner Michael Stott highlights the importance of food and drink companies protecting their intellectual property in order to prevent competitors from exploiting their innovations.

The food and drink sector is the largest manufacturing sector in the UK — larger than the automotive and aerospace sectors combined. It is home to significant innovation, with companies looking to develop new consumer products and striving to keep up with consumer trends, all while ensuring compliance with evolving industry regulation and keeping pace with commitments to improve green credentials. Protecting the intellectual property (IP) resulting from this research and development can help companies to maintain their competitive advantage by preventing others from exploiting the fruits of their labour. However, the full potential of IP is not always harnessed in the food and drink sector. This article is intended to demystify IP in the food and drink industry and shed light on the full extent of the opportunities available to companies to protect and benefit from their IP, with a particular focus on the role patent protection can play.

Research commissioned by the Food and Drink Federation (FDF) in 2018 to identify both the opportunities available to manufacturers and the barriers to growth found that almost nine in 10 (89%) of food and drink manufacturers in the UK were involved in new product development and that nearly half (46%) of respondents have an on-going collaboration with higher education or research initiatives. Clearly, there is a significant focus within the industry on research and development and a consequence of that is the generation of different forms of protectable IP rights that are of varying value to innovative companies, examples of which include:

Patents – these provide protection for products (including food, drink, packaging and machinery), processes (such as recipes or production methods), and uses of products. Granted patent rights provide the patent holder with a temporary monopoly that means that no one can work the invention covered by the patent (for example, make or use a patented product or operate a patented process) without the patent holder’s permission while the patent is in force.

Trade secrets – these can endure indefinitely if the invention remains a secret (which has worked well for Coca-Cola’s original drink formula). However, they provide no protection if another company independently develops the same product or process, or if they successfully reverse engineer a product.

Registered designs – these provide protection for aesthetic aspects of products, such as packaging or aesthetically-pleasing food products. Some protection is also available for designs which have not been registered (unregistered designs).

Trade marks – these identify a product as being from a particular company and include logos (for example, KitKat’s “have a break…”) as well as branding.

Copyright – this comes into existence automatically and protects only against copying of literary, dramatic, musical or artistic works (e.g. artwork on product packaging or the written form of a recipe).

As is evident to many, trademarks and branding play a vital role in distinguishing products and services in the food and drink sector and it is therefore no surprise that these IP rights are often the initial focus of food and drink businesses. However, the possibility of patent protection should also be an early consideration for innovative companies for much the same reasons as it is, for instance, in the pharmaceutical and automotive industries. Patents can provide the means to ring-fence an area of innovation so that it cannot be exploited by competitors so as to help reinforce a dominant market position.

Trade secrets, or confidential know-how, have been relied upon historically by the food and drink industry to a varying extent to maintain competitive advantage, typically beyond the maximum lifetime of patent protection (20 years). However, trade secrets are only useful to the extent that it remains possible for the know-how to remain secret, and it remains difficult for other parties to replicate the know-how by, for instance, reverse engineering a product. Trade secrets are therefore not always the most appropriate way to protect innovation, particularly as advances in chemical analysis can make reverse engineering more achievable than it has been previously.

Patent protection represents an alternative form of IP protection that, despite not providing indefinite protection that is potentially possible with trade secrets, has a number of benefits to innovator companies. Not only do patents offer a monopoly right, they are assets that can be used to add value to a business that can be attractive to investors and they can be sold or licenced as with other forms of property. Products covered by granted patent rights can also benefit from corporation tax relief, such as the ‘Patent Box’ in the UK. Granted patent rights can also be a useful marketing tool – a stamp of approval that a new product is innovative and unique.

With all the potential benefits offered by patent protection in the food and drink sector, there still can be misconceptions surrounding exactly what forms of innovation may be eligible for patent protection, and it may come as a surprise to some companies that their innovations could be patent protected. In order to be granted a patent, an invention must be new and represent a non-obvious solution to a technical problem. Although the features of an invention which define a contribution over what was previously known must have technical character, an invention does not have to be complex or necessarily the result of ground-breaking or expensive research to be patentable. Some very familiar food products have been the subject of patent protection, including for example rice cakes (EP1025764), granola bars (US 4,451,488), new orange juice formulations (WO 2004/060083), veggie burgers (EP3125699) and even a fast setting donut glaze (EP2101595).

One more common misconception is that recipes (i.e. product preparation processes) cannot be patented. They can. So long as they fulfil the basic requirements set out above. For instance, a recipe for a new fish and chip batter was found to be patentable on that basis that it reduces oil uptake during the frying process (GB2543623). A new bread recipe was found to be patentable for giving improved textural properties (GB2545647). A recipe for an “egg gel” composition was considered patentable on the basis that it confers the organoleptic properties of fresh egg, whilst providing an extended shelf life to confectionary compared to normal egg-containing products (GB2565178). A recipe for preparing oat milk having improved soluble oat protein content was also found to be patentable (EP2953482). Numerous examples of patented recipes exist.

Innovative companies should also remember that process know-how can be just as patent-eligible as the new products they produce, which can open up different opportunities for potential revenue growth. A new feature of a food manufacture process, for instance, might allow a food product to be made with a desirable texture which obviates the need for certain additives to be used or for certain customer cooking steps (e.g. oil frying) to be implemented. For example, a process for preparing low-fat oven-fries involving a super-heated steam treatment step which confers a texture of normal “French fries” without oil frying at home was found to be patentable (US7560128). Process patents can be particularly useful for innovative companies to licence their technology and open up additional revenue streams and can be particularly useful in supplementing product patents in a company’s portfolio.

According to the FDF, 96% of food and drink manufacturing businesses in the UK are small to medium-sized enterprises. It is these smaller companies that may be less familiar with the patenting process and the benefits to their businesses, yet which are actively innovating and potentially overlooking opportunities to exploit the IP that is being generated. Although the costs of obtaining granted patents are not insignificant, these may seem trivial when weighed against the potential value addition to a business, opportunity to obtain a monopoly in the market place, ability to generate revenue through licencing and opportunity to benefit from corporation tax relief associated with the sales of patented products.

This article was first published on AgFunderNews in December 2019.

T 0318/14 concerns an appeal based on an Examining Division’s decision to reject EP 2429542 on the basis of double patenting. EP ‘542 has identical claims to, and claims priority from, granted patent EP 2251021. The Board of Appeal in T 0318/14 affirmed that while there is no statutory basis for a double patenting rejection under the European Patent Convention, that Enlarged Board of Appeal decisions G 1/05 and G 1/06 set out the principles for such a rejection on the basis that an applicant has “no legitimate interest in proceedings leading to the grant of a second patent for the same subject-matter if he already possesses one granted patent therefor.”

Moreover, while G 1/05 and G 1/06 related to divisional applications claiming the same subject-matter, the Board considered that the principles should not be restricted to such situations. Thus, an interesting question arising in T 0318/14 is: ‘does an additional 12 months of patent term enjoyed by applicant for EP ‘542 versus EP ‘021 constitute a “legitimate interest”?’ Indeed, in decision T 1423/07, the Board held that a legitimate interest did exist in a scenario where there were different applicants for the priority document and later European application claiming the same subject-matter.

Nevertheless, the case law in this area is divergent, thus a referral to the Enlarged Board of Appeal was considered appropriate. The questions referred seek to establish:

- whether a European patent application can be refused if it claims the same subject-matter as a European patent granted to the same applicant, which does not form part of the state of the art;

- if so, the conditions for such a refusal and whether these differ for: applications filed on the same date; divisional applications; or applications and their priority filings; and

- whether, in the latter case, the additional 12 months of patent term constitutes a “legitimate interest”.

Needless to say, having answers to each of the referred questions will improve legal certainty in this somewhat grey area of European patent law.

Mathys & Squire has been recognised by JUVE Patent in its inaugural UK rankings. The guide brings together UK patent practices, solicitors and barristers, who, according to the in-depth research carried out by an independent team of journalists, have a leading reputation in the UK patent law market.

Ranked in the category of patent filing, Mathys & Squire has been specifically noted for its expertise in the fields of pharma and biotechnology; medical technology; chemistry; digital communication and computer technology; electronics; and mechanics, process and mechanical engineering.

Partners Chris Hamer and Jane Clark have been individually recommended for their expertise in chemistry and digital communication and computer technology / mechanics, process and mechanical engineering respectively.

For more information and to see the JUVE Patent UK rankings 2020 in full, please click here.

In this article for Open Access Government, we consider the US and UK definition of trade secrets and the impact on protecting intellectual property.

On 15 August 2019, federal prosecutors in the US charged engineer Anthony Levandowski with the theft of trade secrets from Google. Mr Levandowski had previously worked for Google before setting up his own company, in the field of self-driving vehicles, which was eventually purchased by Uber. Mr Levandowski has been released on a $2 million bond and denies the charge.

Uber already settled a corresponding civil case in relation to the theft of trade secrets in February 2018 for $245 million.

What is a trade secret?

In the UK, a trade secret protects information that is secret, has commercial value because it is secret, and has been subject to reasonable steps to keep it secret by the person in control of that information. For example, the recipe for Coca-Cola would be regarded as a trade secret because it fulfils all of these criteria. The recipe has value because no company can make Coca-Cola using the same recipe as only Coca-Cola knows how to do so.

A trade secret is, therefore, an unregistered right in that it is not necessary to request the right from the government. Instead, it subsists automatically as long as the above criteria are met. This is different from registered rights such as patents. Applying for a patent requires that the applicant discloses how the invention may be implemented to the public.

Criminal element

To a UK patent attorney who is used to dealing with trade secrets under UK law, what is interesting is the criminal nature of the US charges. In the UK there are currently no provisions for someone to be charged in this way.

A corresponding civil case in the UK would revolve around the breach of confidentiality, rather than the theft of the intellectual property. As trade secrets are unregistered in UK law they cannot be stolen per se; instead only the obligation to keep them secret can be breached. This means that under current UK law it is not possible to pursue a criminal prosecution directly for theft of trade secrets although it is possible that in the act of stealing trade secrets another crime may be committed that could be prosecuted.

Intellectual property (IP) is a form of property and people may find it is strange that the theft of this property cannot result in a criminal conviction. Indeed, IP is often very valuable hence the $245 million settlement in the US civil case. If someone robbed a bank for such a sum, a long custodial sentence would apply.

Moreover, the UK has recently changed the law so that certain breaches of IP can result in criminal convictions. In 2014, the UK introduced a new criminal offence for the infringement of a registered design, in cases where the infringer is aware that the design is registered.

It, therefore, seems incongruous that the deliberate theft of trade secrets does not have associated with it a criminal offence in this country. This may act as a deterrent to stop others from this practice which can be very damaging to companies. Having such criminal offences in the statute may also promote the UK as a place in which research can be undertaken in the knowledge that the state will help police any theft of the fruits of the research.

How are trade secrets used?

At Mathys & Squire, we specialise in providing commercially relevant advice in all fields of IP, covering patents, trade marks, designs and litigation. For example, as a chartered patent attorney, when a client is filing a new patent application we often ask whether there are certain aspects of the disclosure that the client would rather not be made public.

When filing any patent the trade-off between the registered right, and the public disclosure is important to consider. In the case where the disclosure of some minor implementation details will likely not be relevant to the patentability of the invention, we often advise that these details are not disclosed. This is especially the case now that the ‘best mode’ requirement of US patent law has been removed.

This means that it is now no longer necessary to publicly disclose the best way of implementing the invention in order to get a US patent. As such, there is more scope for keeping certain details secret whilst still applying for patent protection to cover a broad invention.

Having multiple rights can be commercially useful. For example, if a company has a patent to a product, another patent to a method of manufacture of the product, a design to cover the appearance of the product, and then trade secrets in the implementation details of the manufacturing process (for example, temperature ranges and times for the steps of a process, particular adhesives that may be best suited to the application, or particular numerical methods that may be used in controlling the process), then together these rights can form very strong protection.

The use of trade secrets ensures that competitors will find it difficult to replicate the results of the manufacturing process, whilst the registered rights may be used to exclude competitors from the market altogether. Of course, it may be expensive to instigate court proceedings so seeking to discourage other companies from infringing the patents in the first place is ideal. Trade secrets may achieve this by putting up a larger barrier to entry as more research is required in order to produce a product, and a competitor may not be able to manufacture a product of sufficient quality without knowledge of the trade secrets.

We conduct licence negotiations with our clients. Often these licences are for registered rights, such as patents or designs. However, sometimes a licence for a trade secret can be just as valuable. These licences can be more complex to formulate and negotiate, but they show the value of trade secrets.

Of course, the additional value is that a trade secret lasts as long as it is of commercial value, and is kept secret. A patent lasts 20 years, and so for some concepts, such as the Coca-Cola recipe, a trade secret can be much more valuable.

Top tips

It can be useful to precisely define what information constitutes a trade secret. This way employees are aware explicitly of what information must be kept a secret, and what information cannot be taken with them to a new employer.

When an employee leaves a role there is often a debate as to what information constitutes their know-how, which is theirs to take with them, and what information constitutes a trade secret owned by the employer. Accurately identifying the border between these areas can help, especially in fields in which there is a high turnover of staff.

Another tip is to seek registered rights. For example, applying for a patent or a design may enable a company to gain a monopoly right when the patent or design is granted. This means they have the ability to exclude others from the market-place. This negates the risk of stolen trade secrets, as any other employer will be unable to use them for commercial purposes without infringing your rights.

Click here for more information on how we can help to actively enforce your IP rights in the fight against patent infringement, third party infringement, copyright infringement, trademark infringement and theft of trade secrets.

This article was first published on Open Access Government in November 2019.

Mathys & Squire is delighted to announce that its client, Rotolight, a pioneering British technology company which specialises in creating advanced LED lighting products for the cinematic, broadcast and photographic industries, has secured a second round of equity investment from the Development Capital team at leading UK SME investor business, Octopus Investments.

This funding follows on from Octopus Investments’ previous growth capital investment of £5 million in Rotolight earlier this year (click here for previous news story). As part of the larger Octopus Group, which manages over £8.5bn on behalf of retail and institutional investors, Octopus Investments serves as a long-term partner for Rotolight, and its additional funding will support the next stage of the tech company’s ambitious growth plans, including opening offices in the US and the Netherlands.

Mathys & Squire has worked closely with Rotolight almost since its inception to build the company’s significant portfolio of patents and designs. Widely recognised as a leading innovator in the sector, Rotolight has won over 30 awards for technological excellence.

Rotolight CEO, Rod Aaron Gammons, commented: “We are investing millions of pounds in research and development in order to create products with ground-breaking, industry-first features that save time and money, and enhance the creative possibilities for filmmakers and photographers all over the world.”

Commenting on this recent development, Mathys & Squire partner Dani Kramer, who heads up the team working with Rotolight, said: “We are delighted that our client Rotolight has been successful in securing this further funding. The outstanding work that Rod and his team do in this field is acknowledged in their various accolades and demonstrated through their latest innovation – the Titan™ X2. It is a pleasure to be a part of their success in protecting their IP and maximising the value of their patents and designs.”

For more information, read the full press release from Rotolight here.

Congratulations to the Rotolight team!

In this article for Business & Innovation Magazine, we consider the importance of reviewing your intellectual property (IP) at every stage of the product development cycle and making sure you have an adequate IP strategy in place.

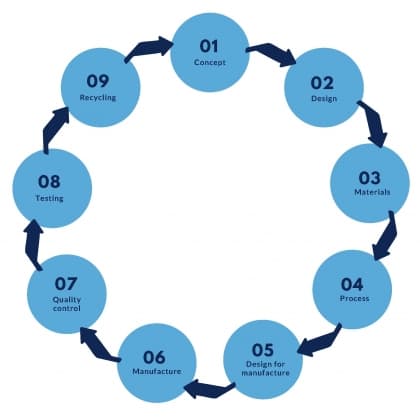

The product development cycle (illustrated below) can be frustrating, especially if you are starting or scaling up a business. It can often take longer, and cost more than expected, so the importance of realistic business plans and budgeting cannot be stressed enough.

As attorneys, we are often asked: ‘When is the best time during the product development process to think about and secure intellectual property?’

The answer is that there is no ‘best’ time or ‘one size fits all’ rule; every case is different and requires a unique strategy. Ideally though, IP would at least be reviewed at every stage of the cycle, to recognise its full value and that your product is adequately protected upon launch.

It is commonly recognised by the business community that a patent can protect a novel technical concept, and that an invention should be kept confidential unless/until a patent application has been filed. What is less clear is when the best time to file this application is. While it is tempting to do so at the concept stage, which may be the right strategy if you need to disclose the invention publicly in order to raise funding, there are some drawbacks.

The invention is likely to evolve over the subsequent stages, so it is important to check along the way that the patent application still covers the invention in its current form and consider ‘topping up’ the application to include new features/technical subject matter within 12 months of filing the application. This deadline applies if the original filing date is to be retained, and if filing corresponding overseas applications.

A registered design (RD) is another type of registered IP, which protects the appearance of a product. Only the product’s appearance is protected, so it’s often best to wait to file an application until it’s ready to be launched. In the UK, US and European community, the law even provides for a so-called ‘grace period’ of 12 months, meaning that you can, in theory, file applications for RDs in those territories up to one year after you have publicly disclosed the product. However, this can be risky, not just because a third party could register something very similar in the intervening period, but also because few other territories offer this allowance, so if your product was disclosed to the public before the effective filing date of your RD in, say, China, the Chinese right would be invalid.

Trade mark (TM) registration also needs to be considered. You may wish to protect your mark in every country that you plan to sell into, but your budget and cash flow must allow for this. Unlike the other registered rights, your TM doesn’t have to be kept confidential until after you have filed a registration application, so an alternative might be to first file in your home markets ahead of the product launch, then file applications for registration in other territories as the market grows, spreading the cost over a longer period of time. It is however important to ensure that you are free to use your chosen TM in the countries to which you are selling (i.e. your use of the TM will not infringe someone else’s rights) and ideally before committing to branded materials.

The message is clear

Get advice early in the product development cycle from a patent or trade mark attorney, and continue to review your IP strategy as the cycle progresses in order to optimise the potential value of your IP and, ultimately, your business. Contact us for a free initial consultation to form a rough strategy of timings and budget for your product development.

This article was first published in the November edition of Business & Innovation Magazine.

The recent ruling of the Nanjing Intermediate People’s Court of Jiangsu Province in a standard essential patent (SEP) royalty dispute between plaintiff Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd., Huawei Terminal Co., Ltd. and Huawei Software Technology Co., Ltd. and defendant Conversant Wireless Licensing Co., Ltd. provides a useful insight into how Chinese courts measure the value of SEPs in the Chinese market.

Background

After acquiring three CN SEP patents (ZL00819208.1, ZL200580038621.8, ZL200680014086.7) from Nokia in 2011/2012 as part of a large patent portfolio acquisition, Conversant contacted Huawei in 2014 about some of the SEPs of the 2G, 3G, 4G and other communication standards used by Huawei that they would need to license from Conversant. However, no agreement was reached between these two companies. In February 2017, Conversant sent a public letter to Huawei, stating that the SEP royalty rate proposed by Huawei in their previous communications did not meet the FRAND requirement.

Meanwhile, in July 2017 in the UK, Conversant sued Huawei and its UK affiliates in the UK High Court, requesting the English court to determine that Huawei infringed four UK patents and rule on the global FRAND license rate for its global patent portfolio (read more here). The court held that Conversant is entitled to enforce its UK SEPs including a FRAND injunction.

Back in China in January 2018, Huawei initiated a non-infringement action against Conversant in the Nanjing Intermediate Court, and requested a determination of SEP royalties for SEPs families including the above three CN patents. Meanwhile, Huawei invalidated all three CN patents, which was been immediately appealed by Conversant. At present, the invalidation case is still under investigation.

Decision

- The court did not support the request by Huawei to confirm that making, disposing and offering to dispose mobile terminal products in China does not infringe the three patents owned by Conversant.

- The SEP royalty rate between Huawei and Conversant in the present case has been confirmed. More details will be discussed in the following section.

- Huawei only needs to pay the above SEP royalty for the 4G mobile terminal products for one patent (ZL200380102135.9).

SEP royalty dispute

In the trial, the dispute centred on the calculation of SEP royalty rates. Conversant proposed to use the Comparable Licenses approach (proposed rates as seen in the left column of the table below), while Huawei proposed to use the Top-Down approach. These two approaches are commonly used in SEP royalty disputes. In the Top-Down method, ‘Top’ refers to the industry’s cumulative royalty, and ‘Down’ refers to the SEP royalty charged by the patentee. In the Comparable Licenses approach, the rates are determined based other license agreements of the same patent. The Nanjing Intermediate Court eventually chose to use the Top-Down approach and set the formula to calculate the Chinese SEP royalty in the present case: the SEP royalty of a single patent family = the cumulative royalty of the standard in China × the contribution ratio of the single patent family. The final calculated SEP royalty is seen in the right column of the table:

| Conversant | Nanjing Intermediate Court |

| Single-mode 2G mobile: 0.032%Multi-mode 3G mobile: 0.181%Multi-mode 4G mobile: 0.13% | Single-mode 2G or 3G terminal product: 0Single-mode 4G terminal product: 0.00225%Multi-mode 2G/3G/4G terminal product: 0.0018% |

Table: A comparison of FRAND royalty proposed by Conversant and ruled by Nanjing Intermediate Court

Conclusion

- This decision provides a useful indication as to how Chinese courts evaluate the value of SEPs in China using the standard of the Chinese market.

- The Comparable Licenses approach in China may be not as important as in other countries because China is not a ‘case-law’ country.

- While the three IP courts (Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou) keep holding their dominant position in IP litigation, a few regional courts have also become popular choices for handling IP cases, for example, the Shenzhen Intermediate Court, the Hangzhou Intermediate Court and the Nanjing Intermediate Court. The Nanjing Intermediate Court is known for speedy trials of technical cases with the help from technical experts, and this case is Nanjing Intermediate Court’s first decision on a SEP Royalty Dispute. We will keep watching whether this decision sets a national standard for SEP Royalty calculation in China.

- As we reported earlier, the IP Tribunal of the Chinese Supreme People’s Court (CSPC) has become a national appeal court since 1 January 2019. In the first trial, the CSPC IP tribunal closed the case within an impressive 50 days, from case acceptance to decision delivery. The decision here of the Nanjing Intermediate Court is open to appeal to the CSPC, and because the CSPC IP tribunal is known to be very fast we would expect a speedy decision if Conversant were to make an appeal to the CSPC IP tribunal.

Mathys & Squire has a dedicated China team with experts from our various sector groups, including IT & software, who keep up to date with the latest industry news in this area. For more information, get in contact with us.

This article was written by technical assistant Sally Gao and managing associate Andrew White.

If the recent weeks of Brexit uncertainty weren’t scream-inducing enough, Halloween is now upon us! Here at Mathys & Squire, we love the scary, the surprising, and most of all the unique, and so we thought we would highlight a few inventions that could make your Halloween celebrations bigger and spookier than ever before…

The decorations

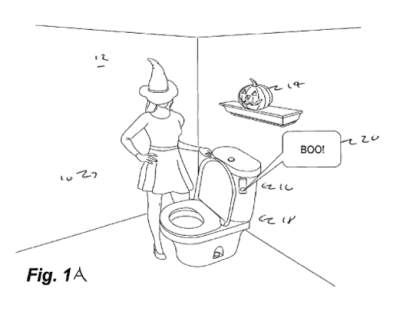

Everyone knows that in order to successfully frighten your party guests, timing is everything – you have to surprise them when they least expect it! With this in mind, US 2012/0060270 discloses an attachable toilet appliance containing a flush responsive audio player. Once triggered, the appliance plays a pre-recorded (and hopefully terrifying) audio message to the user.

Spooky decorations are also a must for any Halloween party, but with increasing demand for healthier food options and a drive to reduce plastic use, how do you frighten your guests whilst being environmentally friendly and avoiding high sugar treats? Fortunately, there seems to be an answer. US 4,827,666 discloses an apparatus for growing squash, cucumbers and other fruits into desired shapes with improved surface details. In particular, US 4,827,666 notes that ‘A zucchini in the likeness of Clark Gable, for example, complete with mustache, would be no ordinary sight on the dinner table’ – we couldn’t agree more – the disembodied head of Clark Gable would indeed be both a uniquely frightening and healthy table decoration!

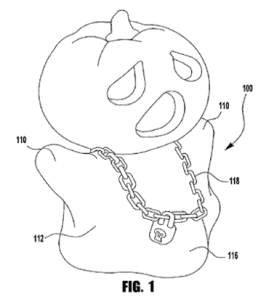

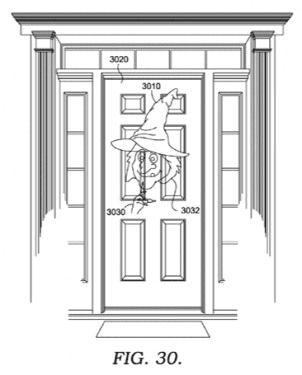

A more traditional Halloween decoration activity involves carving pumpkins, however US 2007/0114336 provides a modernised method of creating these spooky adornments. US 2007/0114336 discloses a decor kit for decorating and accessorising pumpkins, squash, various fruits and vegetables. The kit includes a support base, a covering to surround the support base, and accessories to humanise the carved fruit/vegetable. Our favourite is shown below, we think this ‘hip hop’-looking pumpkin is simply gourd-eous (sorry, at least it wasn’t a Jack the Rapper joke!).

As an alternative, US 2010/0003888 discloses ‘The Regurgitator’, a life size Halloween novelty decoration containing multiple motion sensors triggering different messages when approached from different angles, for example: (Woman screaming with man laughing in background) “THIS IS WHAT YOU GET WHENYOU STAND IN FRONT OF THE REGURGITATOR AAAAAAAAAA” (throw up noises at end). When approached from the front, the man-shaped novelty item will also ‘throw up’ fluid into a metal bucket, while still playing messages. In order to achieve this effect, a fluid jug is located inside the head, wherein fluid contained within the jug will flow through the mouth orifice when triggered. The man-shaped novelty item also contains a bucket attached to the hands in order to catch the expelled fluid.

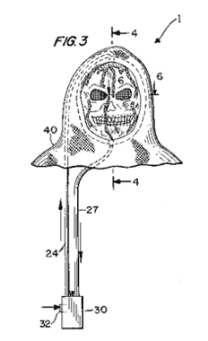

For something a little more high-tech, US 2016/0047536 discloses a novelty decoration which uses light to add human-like features to an inanimate object. The invention includes a film with an image that has been manipulated to provide for a low profile projection of an image onto a vertical surface directly adjacent to the object. The projected image includes an animated face along with audio in the form of music or vocal sounds.

The costume

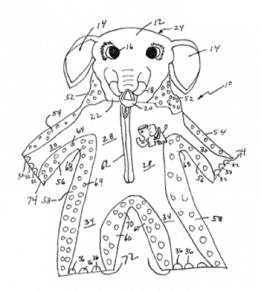

As well as making sure your home is as terrifying as possible, in order to achieve maximum effect, you also need to make sure that you look the part, but how do you decide what to wear when the weather can be so unpredictable? US 2003/0177562 seems to have the solution and discloses a fancy dress costume specifically adapted for changeable weather. In order to improve the comfort of the wearer, this costume is adapted to accommodate not only losses of humidity, but also losses of heat, through the inclusion of vents. Venting is provided in the form of a mesh, net-like material, or other ventilated fabric in the fabrication of the costume. The costume also includes an insulating material disposed over at least a portion of the first garment base.

If your main aim is to scare unsuspecting people, US 6,093,475 discloses a costume element which represents a bleeding body part. The bleeding costume element contains an inner layer which may or may not be transparent and an at least partially transparent outer layer with a passage formed there between. A red blood-like fluid, or any alternative fluid, can be pumped through these passages when desired in order to increase the scariness of your costume as desired.

If you have a ‘ghoulish’ idea for a ‘bloodcurdling’ invention – or any other kind of invention – and need some advice, get in touch with a member of our ‘talon’-ted team today.

The notion of whether or not artificial intelligence (AI) can be deemed eligible as an inventor or not has been challenged recently in the press. In this article for Robotics Law Journal, managing associate Andrew White, an expert in our specialist AI team, explores its implications for patent law.

An artificially intelligent system called DABUS (Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience), developed as part of ‘The Artificial Inventor Project’, is challenging the notion of whether AI can be listed as an ‘inventor’ of patent applications. DABUS has been listed as inventor on two different patent families, pending at the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), European Patent Office (EPO), UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) and Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT).

The AI system, described as a type of ‘Creativity Machine’ by its creator Dr Stephen Thaler, an AI expert based in Missouri, contains a first artificial neural network, made up of a series of smaller neural networks, that has been trained with general information from various knowledge domains, and a second ‘critic’ artificial neural network that acts as a monitor to identify new ideas that are different from its knowledge base.

Can AI be an inventor under current patent laws?

Under the UK Patents Act 1977 and the European Patent Convention, inventorship is restricted to ‘natural persons’. Likewise, in the US, patent laws refer only to ‘individuals’ as eligible inventors. The intention behind this statute was allegedly to stop companies or corporations being listed as inventors (but who can instead own the patent applications) and instead provide recognition to those who developed the inventive concept central to such patents.

In the present case, the Artificial Intelligence Project is keen to emphasise the distinction between inventorship and ownership – while an inventor may often be the owner of an invention, this may not always be the case. For example, employees of a company may have the right to be listed as an inventor, but the patent may belong to the company if the invention was made as part of the inventors’ normal course of duties as part of their employment.

The Artificial Intelligence Project states that its view is that machines should not own patents (but rather the owners of the machines should be the default owner), but that nevertheless the machine should be acknowledged as the inventor if it truly devised the inventive contribution. This is because AI does not have legal personality and, therefore, cannot own property.

What did the AI create?

The inventions contained in the patent applications are described by the Artificial Inventor Project as being the result of an extensive neural system that combines the memories of various learned elements into potential inventions that are then evaluated through the equivalent of affective responses. These affective responses effectively act to either amplify these concepts, or instead general new concepts by generating ‘noise’. The system was previously developed to create surreal art.

One of these inventions is a ‘neural flame’ device, relative to a light-emitting element that flashes at a prescribed frequency and fractal dimension. The other invention relates to a ‘fractal container’, which is a container for beverages that has a wall with a fractal profile which provides a series of fractal elements on the interior and exterior surfaces, forming pits and bulges in the profile which enables multiple containers to be coupled together by inter-engagement of pits and bulges on corresponding ones of the containers. It is claimed that the profile also improves grip, as well as heat transfer into and out of the container.

Is AI likely to be listed as inventors in these cases?

When assessing who should be listed as inventor, while the approach to assessing inventorship is a matter of national law that varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and is not entirely uniform, many jurisdictions require the inventive contribution to be assessed, and then a determination of who came up with the creative or intelligent conception of that inventive contribution – in other words, who came up with the real inventive ‘spark’, i.e. that which distinguishes the invention from that which came before it. This is consistent with the Oxford English Dictionary definition of ‘conception’, which is defined as ‘forming or devising an idea or plan in the mind’.

However the nature of the ‘invention’ is defined, what is generally required is some actual creative or intelligent contribution to the conception phase of the invention, which goes beyond the provision of abstract ideas and the mere execution of ideas on the other. It will be interesting to see where the ideas contained in these patent applications fall on this spectrum.

In the present case, at least, the patent applications are likely to struggle for being formally deficient – for example at the European Patent Office, the applications are likely to fall foul of Article 81 and Rule 19 of the European Patent Convention for not designating the inventor, and if not remedied, refused.

In addition, many people consider that AI is still so primitive at present that it is considered merely a ‘tool’ – it is written by humans, and trained by humans. As such, because it is just a tool, the user of that tool should be listed as the inventor. Many commentators, such as Dr Noam Shemtov, of Queen Mary University of London, who authored a study on inventorship in inventions involving AI activity commissioned by the European Patent Office in February 2019, consider that AI systems that have currently been developed have not yet progressed beyond this stage.

However, with the increasing speed at which AI is developing, it seems that even if in these two cases DABUS is not credited as being the inventor, sooner or later this question will have to be addressed by lawmakers around the world.

Furthermore, it should be noted that aside from the issue of whether or not AI may be listed as inventor in the present case, AI-related inventions (i.e. inventions that make use of AI, for example in drug discovery) are being filed at patent offices around the world at an increasing rate. Many patent offices, such as the European Patent Office, are keen to explain how such inventions are patentable, and recently held a conference in May 2018 on patenting AI inventions.

What are the implications if AI can be listed as an inventor?

Dr Shemtov hypothesises in his study that for an AI to be listed as an inventor under patent laws worldwide, this will require a change to the legal systems and legal frameworks that will involve the creation of a ‘legal or electronic personhood status’. This may be not dissimilar to a system relating to the legal personality of corporations. It may also require a fundamental reassessment of the notion of inventorship with respect to the chain of creation in that it can no longer be based on the idea of creative or intelligent conception, but one which could be described as a ‘functionalist’ approach that looks at the system’s output and contribution.

Although the Artificial Inventor Project states that it considers AI should not own patents because AI does not have legal personality, if indeed AI can be held eligible as inventor, then the question that naturally follows is: why can’t AI then have legal personality also? This would lead to a far-reaching reassessment of ourselves as humans, and society’s relationship with technology. It would have implications for copyright law, civil liability and data protection, to name but a few. For example, with the advent of autonomous vehicles, it may have implications for the question of liability in an accident involving such autonomous vehicles.

Interestingly, the question of whether or not AI may have a legal personality is one that has already been considered by the EU Parliament, who considered that such an assessment of the nature of AI being considered as a legal person was a plausible future development, but one that is currently not warranted by current technical or legal considerations.

This article was originally published in Robotics Law Journal in October 2019.

In Actavis Group PTC EHF and others v ICOS Corporation and another [2019] UKSC 15, the Supreme Court had to consider whether claims directed to a new dosage regime of a drug were obvious. The patent (EP 1173181) was owned by ICOS Corporation and was the subject of an exclusive licence to Eli Lilly & Co. Its claims (including second medical indication claims in both the ‘Swiss-style’ and the newer ‘EPC 2000’ format) covered a dosage regimen of up to 5 mg per day for the compound tadalafil, sold under the brand name Cialis for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Actavis sought to invalidate the patent on the basis of ‘Daugan’, which was the first medical use patent for tadalafil.

At first instance the judge had held that the dosage regime was non-obvious, but this was overturned on appeal. ICOS now sought to reverse the decision of the Court of Appeal.

The Supreme Court upheld the Court of Appeal’s finding of obviousness. In reaching this conclusion, the court listed 10 factors which were ‘relevant considerations’, including whether at the priority date something was ‘obvious to try’ and whether the research leading to the invention was of a ‘routine nature’, as well as whether the results of the research were surprising.

Although ICOS had argued that it was surprising to find that a dosage of 5 mg was effective and associated with reduced side-effects, the court nevertheless agreed with the Court of Appeal that this merely lay “at the end of the familiar path through the routine pre-clinical and clinical trials’ process” given the context of the routine Phase IIb dose-ranging studies in which the dosage had first been tested. Once the dosage had been identified via routine studies, any ‘surprising’ effects associated with it were merely an ‘added benefit’ and not sufficient to confer an inventive step. The court did not provide any guidance as to how the various ‘relevant considerations’ should be weighted, stressing that this would depend on the facts of any particular case. It also explicitly recognised that, in principle, valid dosage regime patents may exist. However, it seems that in many cases dosage regime patents may now be found invalid in the UK unless (for example) there is something unusual or non-routine about the circumstances surrounding identification of the dosage.