Background

The efforts to create a unified patent system in Europe are now well advanced. The agreement on a unified European Patent Court has been coordinated at European level and is now available for ratification by the individual member states of the EU. In order for the agreement to enter into force successfully, it is necessary, among other things, for 13 states to ratify it, including France, the UK and Germany. To date, 16 states have ratified it, including France and the UK. Up until 20 July 2020, the situation was that the only thing missing was ratification in Germany, which was decided in the Bundestag, but against which a constitutional complaint was filed.

Status in Germany

In March 2020, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that the sufficient quorum had not been reached for the decision in the Bundestag. The resolution passed by the Bundestag is therefore not valid. Instead, a new decision is necessary, which must be passed with a two-thirds majority. It is not currently possible to foresee when such a decision can be passed in the current COVID-19 crisis and under the influence of the approaching Bundestag elections next year.

Status in the UK

In April 2018, the UK government ratified the UPC Convention and notified the EU. The UK left the EU on 31 January 2020, and is therefore no longer a member of the EU. As the Unified Patent Court (UPC) Convention only provides for an effect in EU member states, the UPC can no longer have any effect in the UK. According to the present agreement, the central chamber is currently based in Paris, with London and Munich as secondary seats.

On 20 July 2020, the UK actively withdrew its ratification (see full details here).

Opinion of the EU Commission

From the EU Commission’s viewpoint, the ratification process is not affected by Brexit. As can be seen from the 15 July communication, the Commission considers it decisive that the UK was a member of the EU at the time of ratification. The communication also confirms that the UK will no longer participate in the single patent system when it leaves the EU. In relation to ratification, the Commission believes that a legally binding approval in the German Bundestag will bring the Convention into force.

The UK’s withdrawal of the ratification took place only after the communication of the EU Commission, meaning that no statement on this is currently available.

Open questions

It remains questionable whether the withdrawal of the UK ratification prior to the entry into force of the UPC has made it impossible to follow the path prescribed in the Convention. In this case, a possible solution would be for another EU member state to take the place of the UK. It remains to be seen whether this would happen automatically on the basis of the number of patent applications filed by the remaining member states, or whether an EU-wide vote would take place.

One thing that does appear to have been clarified is that a seat of the Central Chamber in London will probably be eliminated.

Visit our Brexit page for more information, or contact the article author, partner Andreas Wietzke, directly.

In this article for Intellectual Property Magazine, Mathys & Squire associate Alexander Robinson analyses the implications of the EPO’s high-profile plant and animal ruling reversal.

In a widely unexpected decision (opinion G3/19), which represents a complete reversal of a position adopted only five years ago, the European Patent Office’s (EPO) highest judicial instance, the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBoA), ruled that plants and animals exclusively obtained by means of “essentially biological processes” cannot be patented.

At the root of the dispute leading to G3/19 is the fact that Article 53(b) of the European Patent Convention (EPC) forbids the patenting of “essentially biological processes for the production of plants or animals”. In its so-called Broccoli/Tomatoes II (G2/12 & G2/13) decisions in 2010, the EBoA clarified that this did not preclude claims to plants or plant material which are obtained through such processes.

This article was published by Intellectual Property Magazine in July 2020 – to read the full version, please click here (subscription required).

Today (15 July 2020) saw the hearing of the EPO Enlarged Board of Appeal in G 1/19 – only the second such hearing ever relating to Computer Implemented Inventions (CIIs) at the EPO. While the case that led to this referral relates to computer simulations, it has the potential to have far-reaching consequences for the patentability of not only simulations, but mathematical methods and their application in computer implemented inventions in general (which is reflected in the large number of amicus curiae briefs filed).

While not being physically present, a number of colleagues at Mathys & Squire LLP attended the hearing virtually via videoconference. The EBoA didn’t issue a decision at the hearing, and the hearing itself was relatively brief. We await their findings with keen interest.

Given the current trajectory of technological development, particularly in the field of machine learning and AI, we are hopeful that the first two questions referred to the Enlarged Board will be answered in the affirmative. To do otherwise might risk development of an unduly negative and restrictive standard for the patentability of CIIs.

Background

EPO Appeals system

Only in rare circumstances, normally where case law developed by Technical Boards of Appeal (TBA) over the years appears to diverge, is a matter referred to the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBoA). For those working in or familiar with the life sciences field, we recently saw such a decision issued in G 3/19 (reported here). In the CII field, the last we had was the referral of the President of the EPO in G 3/08 issued in 2010.

How are CIIs assessed for patentability?

The approach to assessing the patentability of CIIs at the EPO was established in T 641/00 (COMVIK), refined and restated in T 154/04 (Duns Licensing) and expressly approved by the Enlarged Board in G 3/08, the only other referral ever made to the EBoA on this subject.

In summary, the COMVIK approach is first to determine whether the claim includes any technical means (any hardware is enough). Then, if it does (and assuming it is novel) the next step is to determine whether the claim provides a non-obvious technical solution to a technical problem. The EPO does this by assessing which, if any, of the claim features contribute to producing a technical effect. Only those features which do contribute in this way are given any weight when determining obviousness. Those which do not contribute to the solution of a technical problem are deemed to form part of the prior art, given as a “requirements specification” in the objective technical problem to be solved in the “problem and solution” test for inventive step.

A body of established case law in this field has built up over time, and the EPO Guidelines for Examination have also been amended (somewhat recently) to reflect this position.

The revised EPO Guidelines (G-II, 3.3), when discussing the patentability of mathematical methods, note that “A mathematical method may contribute to the technical character of an invention, i.e. contribute to producing a technical effect that serves a technical purpose, by its application to a field of technology and/or by being adapted to a specific technical implementation”. The Guidelines helpfully list a number of examples that may be considered technical, including “simulating the behaviour of an adequately defined class of technical items, or specific technical processes, under technically relevant conditions”.

Importantly, however, the Guidelines and the existing case law suggest that “the mere fact that a mathematical method may serve a technical purpose is not sufficient, either. The claim is to be functionally limited to the technical purpose, either explicitly or implicitly. This can be achieved by establishing a sufficient link between the technical purpose and the mathematical method steps, for example, by specifying how the input and the output of the sequence of mathematical steps relate to the technical purpose so that the mathematical method is causally linked to a technical effect”.

T 1227/05 (Infineon)

A decision that is often referenced in this field is that of T 1227/05 (Infineon). It relates to a computer-implemented method for the numerical simulation of the performance of an electronic circuit subject to noise. The Technical Board of Appeal held the method here to be patentable because the simulation of a circuit subject to a particular type of noise constitutes an adequately defined technical purpose.

Significantly, in the manner it was claimed, the method was functionally limited to that technical purpose. The Board held that a circuit with input channels, noise input channels and output channels whose performance is described by differential equations does indeed constitute an adequately defined class of technical items, the simulation of which may be a functional technical feature.

By contrast, a claim which attempted “the metaspecification of an (undefined) technical purpose” by making mere reference to simulation of a “technical system” was deemed not an adequately defined class of technical items, and therefore not patentable. This contrast may, we believe, be of particular significance in the present referral.

It may also be worth observing that the EPO Guidelines note that “if the claim were not limited to the numerical simulation of an electronic circuit subject to 1/f noise, the mathematical algorithm defined by steps (d1)-(d3) would not serve any technical purpose and would thus not be considered to contribute to the technical character of the claim”.

The appeal (T0489/14) which led to this referral

The appeal, which gave rise to the present referral to the Enlarged Board, relates to “A computer-implemented method of modelling pedestrian crowd movement in an environment”.

The patent application in question indicates that the main purpose of the simulation is its use in a process for designing a venue such as a railway station or a stadium. This is not recited in the claims of the Main and First to Third Auxiliary Requests but it is referenced in the Fourth Auxiliary Request.

Importantly, at Reasons 10 of the decision referring the questions to the EBA, the TBA held (emphasis added):

“10. As to the technicality of simulating crowd movement, the appellant argued that simulating the movement of pedestrians yielded results which were no different from those obtained by modelling an electron using numerical methods. Like the simulation of an electron, the claimed simulation of the movement of pedestrians was based, at least in part, on the laws of physics.

The Board does not disagree with these observations but is not convinced that numerically calculating the trajectory of an object as determined by the laws of physics is in itself a technical task producing a technical effect.”

The Board went on to state (emphasis added):

“11. In the Board’s view, a technical effect requires, at a minimum, a direct link with physical reality, such as a change in or a measurement of a physical entity. Such a link is not present where, for example, the parabolic trajectory followed by a hypothetical object under the influence of gravity is calculated. Nor can the Board detect such a direct link in the process of calculating the trajectories of hypothetical pedestrians as they move through a modelled environment, which is what is claimed here. In fact, the environment being modelled may not exist and may never exist. And the simulation could be run to support purely theoretical scientific investigations, or it could be used to simulate the movement of pedestrians through the virtual world of a video game.

In this context, the Board notes that the Enlarged Board of Appeal in decision G 2/07, reasons 6.4.2.1, stated that “[h]uman intervention, to bring about a result by utilising the forces of nature, pertains to the core of what an invention is understood to be“. It appears to the Board that using a computer to calculate the trajectories of hypothetical pedestrians as they move through a modelled environment does not utilise the forces of nature to bring about a result in any way different from using a computer to perform any other type of calculation.”

The Appellant had referred during the hearing to T 1227/05 (Infineon) and drawn the analogy that simulating the performance of a modelled electrical circuit (which was held patentable there) is much the same as simulating the behaviour of a modelled environment. In the subsequent written decision, the Board agreed with the Appellant’s arguments that T 1227/05 supported their case but noted that they were “not fully convinced by the decision’s reasoning”. They gave two reasons:

“First, although a computer-implemented simulation of a circuit or environment is a tool that can perform a function “typical of modern engineering work”, it assists the engineer only in the cognitive process of verifying the design of the circuit or environment, i.e. of studying the behaviour of the virtual circuit or environment designed. The circuit or environment, when realised, may be a technical object, but the cognitive process of theoretically verifying its design appears to be fundamentally non-technical.”

“Second, the decision appears to rely on the greater speed of the computer-implemented method as an argument for finding technicality. But any algorithmically specified procedure that can be carried out mentally can be carried out more quickly if implemented on a computer, and it is not the case that the implementation of a non-technical method on a computer necessarily results in a process providing a technical contribution going beyond its computer implementation (see e.g. decision T 1670/07 of 11 July 2013, reasons 9).”

The Board also noted that T1227/05 acknowledged a tension with an earlier decision in T 435/91 which required a step of “materially producing the chip so designed” thus tying the subject matter explicitly to a real-world object. The Board noted the growing importance of “numerical development tools” and in particular CIIs, and that “legal certainty in respect of the patentability of such tools is highly desirable”. The Board therefore referred three questions for consideration by the Enlarged Board.

Questions referred to the EBoA

1. In the assessment of inventive step, can the computer-implemented simulation of a technical system or process solve a technical problem by producing a technical effect which goes beyond the simulation’s implementation on a computer, if the computer-implemented simulation is claimed as such?

2. If the answer to the first question is yes, what are the relevant criteria for assessing whether a computer-implemented simulation claimed as such solves a technical problem? In particular, is it a sufficient condition that the simulation is based, at least in part, on technical principles underlying the simulated system or process?

3. What are the answers to the first and second questions if the computer-implemented simulation is claimed as part of a design process, in particular for verifying a design?

The first question

The first question suggests that the applicability of the widely-accepted approach to assessing the patentability of CIIs under inventive step (Article 56 EPC) following the COMVIK decision (T 641/00) is not in question.

However, by using the language “computer implemented simulation of a technical system” (emphasis added) in the question, this presupposes that the system is already technical – which may not be the case here where the system is the behaviour of pedestrians. Instead, the system may be held to be non-technical because, following the reasoning of a very recent decision taken in T 1798/13, it “is not a technical system that the skilled person can improve, or even simulate with the purpose of trying to improve it”.

The use of “as such” language in question 2 was commented on in the amicus briefs because of its apparent relevance to the wording of Article 52(2) EPC, but these issues weren’t raised at the hearing. It remains to be seen whether they will be addressed in the written decision.

The second question

The second question seems to address the idea of whether the simulation is (as set out in the Guidelines) “functionally limited to a technical purpose”.

The EPO’s current Guidelines for Examination say that a generic purpose, such as “simulating or controlling a technical system” is not sufficient, but rather that the technical purpose must be a specific one. Moreover, the mere fact that the mathematical method may possibly serve a technical purpose is not sufficient, either – as held in T 1227/05, the claim must be functionally limited to a specific technical purpose, either explicitly or implicitly.

Interestingly, the EPO Guidelines also note (at G-II, 3.3.2) “In the context of computer-aided design of a specific technical object (product, system or process), the determination of a technical parameter which is intrinsically linked to the functioning of the technical object, where the determination is based on technical considerations, is a technical purpose”.

These Guidelines are of course not binding on the Enlarged Board. Indeed, the Enlarged Board’s answer to the second referral question may very well have direct implications for future revisions of these parts of the Guidelines, and if so a direct impact on practice before Examining Divisions at the EPO.

The third question

The third questions seems most relevant to the claims of the Fourth Auxiliary Request under appeal – where the claims are directed to a method of designing (a model of) a building structure. The TBA noted that this additional step “arguably strengthens the appellant’s case” that T 1227/05 is relevant yet noted that their view was that it didn’t help as “a direct link with physical reality is still absent”.

Our observations of today’s hearing

During the hearing it was interesting that both the Appellant and the President of the EPO argued in favour of computer simulations as such being technical, with the Appellant arguing that simulations serve a technical purpose and therefore must provide a technical effect.

With respect to the second question, both the Appellant and President made analogies between physical and virtual wind-tunnel tests. They both argued in essence that such simulations rely on technical considerations and therefore have to be regarded as technical – in some sense agreeing with the position set out in the EPO Guidelines at G-II, 3.3.2 but they may perhaps have gone further than this in the arguments they made. The President made further reference to an example of raytracing (commonly used in computer games), noting that the raytracing process is based on technical considerations even if the generated imaged is fictitious.

The EBoA didn’t decide anything today, and the overall hearing was relatively brief. They will likely now take some time to consider the submissions, along with the many amicus curiae briefs before issuing their written decision and minutes of the hearing. However, the consensus view amongst our colleagues who ‘attended’ the virtual hearing is that the first two questions should be held in the affirmative. In our view, deciding otherwise may create a relatively negative and restrictive view on the patentability of CIIs in the future, as well as having an adverse knock-on effect on past cases and in protecting AI inventions more widely.

The EPO’s May 2020 decision in G3/19, on the patentability of certain plants, was among the most controversial in the office’s history. In this article for Life Sciences Intellectual Property Review, Mathys & Squire partner Anna Gregson explores the implications.

In its decision G3/19, issued in May, the European Patent Office’s (EPO) Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBA) held that plants, plant material, and animals exclusively obtained by an essentially biological process are not patentable.

G3/19 is the latest chapter in a 20-year history of the protection of plant-related innovation, beginning with the introduction of the EU Biotech Directive in 1998. Before G3/19, the EBA’s last contribution to this saga was the issuance of the consolidated G2/12 and G2/13 (Tomatoes II and Broccoli II) in March 2015.

In those decisions, the EBA concluded that the exclusion of essentially biological processes for the production of plants in article 53(b) of the European Patent Convention (EPC) did not have a negative effect on the allowability of a product claim directed to plants or plant material. These decisions were not popular in some EPC member states, which led to the EU Commission issuing a guidance notice in November 2016 to the effect that the Biotech Directive excluded such products from patentability.

This article was published by LSIPR in July 2020 – to read the full version, please click here (subscription required).

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), the EU’s highest court, has issued its decision in case C-673/18 (Santen). The ruling relates to the interpretation of Article 3(d) of the SPC regulation and it represents a significant divergence from the court’s previous case law. The CJEU’s judgment has negative implications for many SPC applications based on new authorisations for older products (e.g. new medical indications) and is likely to come as a body-blow to pharmaceutical innovator companies. Applicants will need to review their existing SPC portfolios, and revisit their filing strategies for new SPCs.

Santen’s SPC application related to the product, ciclosporin, and was based on a marketing authorisation (‘MA’) that authorised the product for the treatment of keratitis. The application was rejected by the French Patent Office (INPI) because a previous MA had been granted for ciclosporin in 1983, albeit for a different therapeutic indication. The INPI held that the SPC application contravened Article 3(d) of the SPC regulation, because the SPC for ciclosporin was not based on “the first authorisation to place the product on the market as a medicinal product”. Santen appealed this decision, arguing that the SPC should be granted, based on the CJEU’s judgment from 2012 in the Neurim case (C-130/11).

In the Neurim judgment, the question arose as to what is the first MA for SPC purposes under Article 3(d). Neurim had applied for an SPC for the product melatonin based on a patent claiming a certain medical use of melatonin and an MA for melatonin corresponding to the claimed medical use. The SPC application was initially rejected because Neurim had failed to identify an earlier, veterinary MA for melatonin as the first MA in the jurisdiction, notwithstanding the fact that the earlier veterinary use was directed to a different use and was not covered by Neurim’s claims. The CJEU viewed things differently, however, holding that the earlier veterinary MA was no obstacle to an SPC based on a later MA, because the first MA for SPC purposes was one which fell within the limits of protection of the basic patent.

The CJEU ruled in Neurim that, when correctly interpreted, the legislation ‘refers to the marketing authorisation of a product which comes within the limits of the protection conferred by the basic patent relied upon for the purposes of the application for the supplementary protection certificate’. As the veterinary MA for melatonin did not fall within the scope of the patent, it could not be the first MA. Based on this ruling, many patent offices across Europe have granted SPCs for new uses of previously authorised products, even if the earlier authorisation was also for use in humans (unlike the factual situation underlying Neurim).

The Paris Court of Appeal in Santen referred various questions to the CJEU seeking to clarify the scope of the Neurim judgment, to determine the extent to which it could be applied to the Santen application. The CJEU has now answered these questions as follows:

‘Article 3(d) of Regulation (EC) No 469/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 May 2009 concerning the supplementary protection certificate for medicinal products must be interpreted as meaning that a marketing authorisation cannot be considered to be the first marketing authorisation, for the purpose of that provision, where it covers a new therapeutic application of an active ingredient, or of a combination of active ingredients, and that active ingredient or combination has already been the subject of a marketing authorisation for a different therapeutic application.’

In arriving at this conclusion, the CJEU noted that Article 3(d) makes no reference to the limits of protection of the basic patent and stated that ‘contrary to what the Court held in paragraph 27 of the judgment in Neurim, to define the concept of ‘first [MA for the product] as a medicinal product’ for the purpose of Article 3(d) of Regulation No 469/2009, there is no need to take into account the limits of the protection of the basic patent’.

This is consistent with a direction of travel towards a stricter interpretation of the SPC Regulation which was hinted at in last year’s Abraxis decision (C-443/17), in which the CJEU ruled that SPCs could not be granted on the basis of a new MA for a new formulation of a previously-authorised active ingredient. The Court now appears to have gone one step further by contradicting the Neurim judgment itself. Careful consideration of SPC filing strategies will be necessary to mitigate the negative implications of the Santen judgment for SPCs which relied on Neurim.

The trend towards an increasingly strict interpretation of the SPC Regulation will renew debate about whether the protection available under the Regulation, which is now almost 30 years old, is suitable for the needs of the modern pharmaceutical industry. The European Commission is currently reviewing the Regulation with a view to possible revision. Meanwhile, with the CJEU’s jurisdiction in the UK due to lapse at the end of this year, a post-Brexit UK could potentially consider whether a more liberal domestic SPC regime is called for.

For further information on SPCs, visit our specialist page, or contact one of the authors of this article, Peter Arch, Alexander Robinson, David Miller or Stephen Garner.

The German Federal Court of Justice (the Supreme Court) recently issued its written decision in the ongoing dispute between Sisvel v Haier (KZR 36/17). Sisvel manages an LTE and LTE-A (4G) patent pool mainly based on a raft of 4G essential patents acquired from Nokia in 2011/12.

In this decision the Federal Court of Justice made explicit reference to UK case law by citing Judge Justice Birss (J. Birss) in the decision of Unwired Planet v Huawei [2017] EWHC 711 (Pat), and held that an infringer of a Standards Essential Patent (SEP) bears a responsibility to participate in the licence agreement negotiations in a “target-oriented manner” and that “delay tactics” are not consistent with a willingness to conclude a licence agreement in a target-oriented manner.

The decision also holds that a patentee does not have to offer licences at a “uniform tariff” for them to be considered FRAND, which may well have ramifications for how royalty rates of SEPs are calculated for use in other sectors such as the automotive sector.

Facts of the case

The present case was based on European patent EP 852885, originally filed by Nokia in 1996 which relates to data rate negotiation during call set-up between a mobile station and a mobile communication network.

Haier distributed and offered mobile phones and tablets at the International Electronics Fair in Berlin in September 2014. Sisvel considered that these mobile phones and tablets supported the GPRS standard which are under the responsibility of the European Telecommunications Standard Institute (ETSI). In April 2013, Sisvel had made a commitment to ETSI (as they are required to do if they wish to include patents as part of the standard set by ETSI) to licence to Haier the patent on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms, and approached Haier accordingly.

The parties could not agree, so in 2014 Sisvel sued Haier. Sisvel considered the offer of the mobile phones and tablets to infringe their patent rights and ordered Haier to cease and desist, provide information, render accounts, destroy and recall the goods and to establish their obligation to pay damages. The German Regional Court in Düsseldorf sentenced Haier accordingly, finding the patent valid and infringed and dismissing a defence from Haier on the grounds that they had delayed negotiations.

However, at appeal, the Higher Regional Court in Düsseldorf, while finding the patent to still be valid and infringed, did not grant an injunction as it considered Sisvel’s offer to Haier not to be FRAND because its offer to Haier was higher than an offer it had made to another party (Hisense, a Chinese phone maker). In their defence, Sisvel argued that the rate offered to Hisense was below-FRAND due to special circumstances relating to that deal.

Abuse of a dominant position

The decision of the Higher Regional Court in Düsseldorf was appealed to the German Federal Court of Justice, who found that Sisvel as owner of the patent were dominant, in short because the patented technology cannot be substituted by a different technology and still comply with the relevant standard (in continental Europe the issue of SEP disputes is normally decided under the umbrella of competition law, whereas in the UK it is normally under the umbrella of contract law). Because Sisvel were in a dominant position, the question was therefore whether they had abused this dominant position.

The Federal Court did not agree with the Higher Regional Court that this meant that Sisvel had necessarily abused its dominant position. Instead, the Federal Court held that (roughly translated into English from German):

“An action brought by a market-dominant patent holder who has undertaken vis-à-vis a standardization organization to grant licences on FRAND terms may constitute an abuse of his dominant position if and to the extent that it is suitable to prevent products conforming to the standard from entering or remaining available on the market.”

The Federal Court noted that while applications for injunctive relief can be abusive, the owner of an SEP is not prohibited from enforcing their patent by requesting injunctive relief. Instead, an abuse is only found if the infringer is not prepared to take a licence for the SEP on reasonable and non-discriminatory terms, with the Federal Court stating that:

“It therefore constitutes an abuse of the dominant position if the patentee asserts claims for injunction, destruction and recall of products although the infringer has made him an unconditional offer to conclude a licence agreement on conditions which the patentee may not refuse without violating the prohibition of abuse or discrimination.

In addition, an action for assertion of such claims may also be considered abusive if the infringer has not (yet) agreed to conclude a licence agreement under certain reasonable conditions, but the patent proprietor bears the responsibility for this as he has not made sufficient efforts to meet the special responsibility associated with the dominant position and to enable an infringer who is in principle willing to licence to conclude a licence agreement under reasonable conditions.”

In short, the patent proprietor bears a special responsibility in light of their dominant position to sufficiently engage in negotiations for a licence agreement under FRAND conditions.

Non-discriminatory

On the question of whether or not the rate offered to Hisense meant that the offer made to Haier was not FRAND, importantly the Federal Court held that:

“The dominant patentee is not in principle obliged to grant licences in the manner of a “uniform tariff” which grants equal conditions to all users.”

In short, therefore, a patentee is allowed to accept different contractual terms and licence rates if there is an objective justification for the differentiation – for example if they are the best that can be commercially achieved:

“Since appropriate conditions for a contractual relationship, in particular an appropriate price, are regularly not objectively determined, but can only be determined as the result of (possibly similar) negotiated market processes, the serious and goal-oriented participation of the company seeking a licence in the negotiation of appropriate contractual conditions is of decisive importance.”

Onus on the infringer to be willing

However, the infringer also bears a responsibility to be willing– with the Federal Court noting that:

“the infringer, for his part, must clearly and unequivocally declare his willingness to conclude a licence agreement with the patent proprietor on reasonable and non-discriminatory terms and must also subsequently participate in the licence agreement negotiations in a target-oriented manner”.

The Federal Court then made explicit reference to UK case law and cited the decision of J. Birss in Unwired Planet v Huawei [2017] EWHC 711 (Pat) (read Mathys & Squire’s article on this decision here) where J. Birss stated:

“A willing licensee must be one willing to take a FRAND licence on whatever terms are in fact FRAND.”

The Federal Court made it clear that while an infringer may request sufficient information to make a specific FRAND offer, delay tactics are not consistent with a willingness to conclude a licence agreement in a target-oriented manner. The Federal Court noted that the Higher Regional Court had incorrectly assumed that Haier had agreed to conclude a licence agreement on FRAND terms and stating that:

“The Court of Appeal correctly saw that the defendant’s declaration of 12 December 2013, i.e. more than one year after the first infringement notification, did not meet the requirements for an infringer willing to obtain a licence in terms of time alone. An infringer who remains silent for several months on the infringement notification thus regularly indicates that he is not interested in obtaining a licence.”

Conclusion

The Federal Court of Justice therefore found in favour of Sisvel and further awarded damages, holding that they did not in principle constitute an abuse of a dominant position as a patentee can only counter a patentee’s claim for damages with a claim for damages of their own.

UK perspective

While there are differences in how SEP FRAND disputes are handled in the UK and Germany due to the differing application of contract and competition law, the specific references to UK case law in this German Federal Court of Justice decision suggests we are likely to see a more uniform handling of SEP FRAND disputes across Europe.

Furthermore, importantly the finding that a FRAND rate is not set in stone and can vary raises important considerations for other sectors such as the automotive sector. In the telecoms sector, SEP FRAND royalty rates may be calculated as a % of handset sales price – typically 5% for 3G SEPs and as much as 10% for 4G SEPs. Such a calculation wouldn’t seem fair in the automotive field where arguably the importance of the telecommunications technology that is the focus of the SEPs is less than it is for a mobile device. The present decision may therefore pave the way for differing royalty rate calculations depending on the field of use.

German perspective

The Federal Court of Justice follows the steps for FRAND negotiations established by Huawei/ZTE (C-170/13) and the obligations for both parties. It should be noted that the wording used in the communication between the parties could make the difference in assessing if a licence offer or the declaration of willingness to take a licence is in line with the mentioned obligations. Particular care should be taken when such communication is handled on the business side at corporate decision maker level without involvement of the litigation team.

Additionally, the decision mentions the admissibility of portfolio licence deals even if only one patent is part of the infringement litigation. Those potential portfolio licence deals are restricted only that the infringer is not forced to sign up for licence for non-SEPs and that the infringer who plans a product only in a limited geographical area has no disadvantage from such deal. While the geographical restriction is usually less important for telecommunications cases, this may have an impact on how SEP owners have to bundle their patent portfolios.

The Supreme Court judgment (24 June 2020) sends a clear “no” Brexit message to any big pharma contemplating corporate muscle-flexing of excessively broad patent claims. This ruling overturned the position held by the Court of Appeal that, for patents relating to “a principle of general application”, there was no requirement to teach how to make the full range of claimed products. In this regard, the Court of Appeal held that Regeneron’s contribution to the field extended beyond the products (transgenic mice) that could be made back in 2001, and instead related to the general principle of providing ‘better’ mice (thereby overcoming a prior art immuno-sickness problem inherent to mice transfected with human DNA). With hindsight, the Court of Appeal allowed too much weight to be given to post-invention evidence of success submitted by Regeneron, and to the relative contribution the ‘better’ mice aspect provided in producing a(ny) mouse having commercial utility. In sum, the Supreme Court considered the Court of Appeal had incorrectly watered down the “sufficiency of disclosure” requirement of patent law and, in doing so, this judgment maintains a sensible balance between patent law enforceability and invalidity.

Background to the case

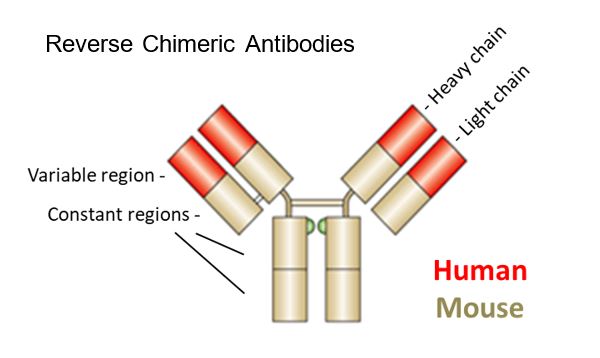

Regeneron obtained two patents with a priority date of 16 February 2001, EP(UK) 1 360 287 (“the 287 Patent”) and EP (UK) 2 264 163 (“the 163 Patent”, a divisional of the 287 Patent). At the priority date there were two main problems associated with the use of mice as a platform for antibody development. First, use of murine antibodies in humans typically resulted in a host rejection response. Secondly, the transfection of mice with human antibody genes was associated with the mice developing a reduced immune response function (and thus reduced antibody titres). Regeneron’s solution to this reduced antibody production capability was to develop a hybrid (chimeric) antibody gene structure, consisting in part of human and in part of murine elements, created by insertion of ‘human variable regions’ into the genome of the mouse, whilst retaining the ‘mouse constant regions’. It is, of course, the ‘variable’ regions that are primarily responsible for antibody recognition of its target antigen, and thus essential for generating antibodies against new targets.

Kymab’s challenge to validity arose in defence to an infringement action brought by Regeneron against Kymab’s commercialisation of its own transgenic mice, “Kymouse”. At first instance (Patents Court), Mr Justice Henry Carr [[2016] EWHC 87 (Pat)] found that the difficulties in producing a hybrid gene structure where the whole of the human variable region was combined with the murine constant region were not taught (enabled) by the technical disclosures offered by the Regeneron patents (even when combined with the common general knowledge at the time of the priority filing), concluding that “at the priority date, the skilled person would not have been able to perform the invention over the whole area claimed without undue burden and without needing inventive skill”. This decision was overturned by the Court of Appeal [[2018] EWCA Civ 671], holding that Regeneron’s patents contained enough information to insert some of the human material into a mouse’s genes. Whilst this would have created a hybrid mouse (as claimed), the prevailing genetic manipulation techniques available imposed a significant limitation on the amount of human DNA that could be transferred. Indeed, said limitations would, at best, have permitted the transfer of up to 5% of the human variable region V segments into a mouse genome. Moreover, the necessary transfection techniques required for transfer of the full human repertoire were not invented until 2011. Thus, the Regeneron patents taught how to make a transgenic mouse having up to 5% of the necessary human repertoire, which as such simply had no meaningful commercial utility. Despite this, however, the Court of Appeal upheld the Regeneron patents on the basis they related to a “principle of general application”, and did not therefore require any teaching of how to make products commensurate with the scope of the claims. Kymab appealed to the Supreme Court.

The claim in question covers a range of mice

The case turned on the relevance or otherwise, of the existence of a very narrow range of mice having amounts (up to 5%) of the human variable domain repertoire, to the question of sufficiency. The appellant submitted that the range was of the highest importance because of its effect upon the ability of a particular type of mouse to produce a wide variety of B cells, and hence its potential to deliver a broad stream of useful antibodies (and thus have an meaningful commercial utility). The respondent/patentee submitted that the existence of this range was irrelevant, because the unique advantage conferred by the use of a Reverse Chimeric Locus, namely a cure for the immunological sickness of the recipient mouse, worked across the whole range, regardless of the amount of the human variable region DNA inserted into the murine genome, because it retained the murine constant region genes.

Lord Briggs reviewed of sufficiency in the UK and EPO

In considering UK cases (Biogen Inc v Medeva plc [1995] RPC 25 and [1997] RPC 1, Kirin-Amgen Inc v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd [2005] RPC 9 Generics (UK) Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2008]; Lord Briggs found that the UK case law provides clear guidance for product claims, in contrast to the situation for a process such as described (EPO case law) in ‘Polypeptides’ (Genentech I/Polypeptide expression (1988) (T 292/85) 1988), reciting Hoffmann on insufficient disclosure: “The patent may claim results which it does not enable, such as making a wide class of products when it enables only one of those products and discloses no principle which would enable others to be made.” (Biogen) “In the case of a product claim, performing the invention for the purposes of section 72(1)(c) means making or otherwise obtaining the product. In the case of a process claim, it means working the process. A product claim is therefore sufficiently enabled if the specification discloses how to make it” (emphasis added).

Lord Briggs set out principles for determining sufficiency

i) The following principles for determining sufficiency were outlined [56]:The requirement of sufficiency imposed by Article 83 of the EPC exists to ensure that the extent of the monopoly conferred by the patent corresponds with the extent of the contribution which it makes to the art.

ii) In the case of a product claim, the contribution to the art is the ability of the skilled person to make the product itself, rather than (if different) the invention.

iii) Patentees are free to choose how widely to frame the range of products for which they claim protection. But they need to ensure that they make no broader claim than is enabled by their disclosure.

iv) The disclosure required of the patentee is such as will, coupled with the common general knowledge existing as at the priority date, be sufficient to enable the skilled person to make substantially all the types or embodiments of products within the scope of the claim. That is what, in the context of a product claim, enablement means.

v) A claim which seeks to protect products which cannot be made by the skilled person using the disclosure in the patent will, subject to de minimis or wholly irrelevant exceptions, be bound to exceed the contribution to the art made by the patent, measured as it must be at the priority date.

vi) This does not mean that the patentee has to demonstrate in the disclosure that every embodiment within the scope of the claim has been tried, tested and proved to have been enabled to be made. Patentees may rely, if they can, upon a principle of general application if it would appear reasonably likely to enable the whole range of products within the scope of the claim to be made. But they take the risk, if challenged, that the supposed general principle will be proved at trial not in fact to enable a significant, relevant, part of the claimed range to be made, as at the priority date.

vii) Nor will a claim which in substance passes the sufficiency test be defeated by dividing the product claim into a range denominated by some wholly irrelevant factor, such as the length of a mouse’s tail. The requirement to show enablement across the whole scope of the claim applies only across a relevant range. Put broadly, the range will be relevant if it is denominated by reference to a variable which significantly affects the value or utility of the product in achieving the purpose for which it is to be made.

viii) Enablement across the scope of a product claim is not established merely by showing that all products within the relevant range will, if and when they can be made, deliver the same general benefit intended to be generated by the invention, regardless how valuable and ground-breaking that invention may prove to be.

Application of those principles to the current case shows that Claim 1 fails for insufficiency, because only a small range of the products could be made, and mice at the more valuable end of the range could not be made.

Interesting observations (unusual nature of the Court of Appeal Order)

Kymab obtained a stay of injunction, order for delivery up and disclosure granted pending an application to appeal to the Supreme Court in respect of Kymab’s collaborative work with humanitarian bodies including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative to treat diseases with unmet clinical need. Under the terms of the stay, Kymab was permitted to ‘dispose or export’ antibodies or mouse serum for the purposes of:

Kymab’s collaborations with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and Heptares Therapeutics Limited; and

For preparing and conducting pre-clinical or clinical trials, antibody producing CHO cells for use by Kymab’s manufacturing CRO Lonza (and which will remain under Kymab’s control) solely for the purposes of manufacturing antibodies under GMP conditions for use in pre-clinical or clinical trials.

Summary

A patent reflects a bargain between the inventor and the public. The inventor gains a time-limited monopoly over the making and use of a product. In return, the public gains the ability to make the product after the expiry of the monopoly. As part of this bargain, the inventor must publish sufficient information to enable a skilled member of the public to make the product. This ensures that patent holders only gain legal protection which is proportional to their actual technical contribution to the art, and encourages inventors to conduct research for the benefit of society. The decision makes a clear distinction between the requirements for a product claim (that the product can be made across the breadth of the claimed range at the effective date of the patent), and a process claim, where the process can be applied to a range of inputs, and will always provide the benefit. Whereas the Court of Appeal gave the patentee a tantalising glimpse of a world where the patentee might receive the benefit for having a good idea, even though they couldn’t make it work across the board, this decision puts the balance back firmly with the public.

For a second year, Mathys & Squire has been ranked as a leading European patent firm as part of the Financial Times’ report: Europe’s Leading Patent Law Firms 2020.

Based on recommendations made by clients and peers, alongside our leading firm ranking for patent prosecution and strategy consultation services, Mathys & Squire has also been recommended for its industrial expertise in the following sectors: Chemistry & Pharmaceuticals and Electrical Engineering.

As part of the research, recommendations from over 2,900 clients and peers were considered, which generated a list of 160 recommended patent law firms from across Europe.

We would like to thank all our clients and contacts who have taken the time to recommended the firm as part of the FT’s research.

To access the full report and rankings tables, please visit the FT website here.

The CJEU has ruled that the shape of technical designs may be eligible for copyright protection, even if the shape is partially dictated by technical function.

This ruling, issued on 11 June 2020, came as a result of a referral from Belgium in a dispute between Brompton, makers of the well-known Brompton foldable bike, and Korean company Get2Get, which manufactures a similar foldable bike. The Brompton bike had previously enjoyed patent protection but, since this has now expired, Brompton brought a case against Get2Get for infringement of their copyright in the shape of their folding bicycle. Get2Get argued that they were simply copying the technical aspect of the foldability of the bike and this inevitably led to a similarity in shape. Therefore, they reasoned, this was not protected by copyright as it was dictated by technical function. While the CJEU agreed that copyright protection does not apply when the shape of a design is dictated solely by technical considerations, it has ruled that copyright may still subsist in a design where the shape is only partially dictated by function. The only criterion is that the design fulfills the originality standard for copyright protection – namely that it is the author’s own intellectual creation resulting from free and creative choices.

Copyright protection in the UK and Europe arises automatically and provides a much longer term of protection than that conferred by patents and designs. Even though an article has previously enjoyed another form of IP protection such as a patent, this decision highlights that it is not precluded from continuing to enjoy copyright protection beyond expiry of this alternative right. Therefore, this ruling emphasises how copyright may form an additional tool in enforcing rights against potential copycat-infringers.

For more information on the protection and registration of designs, visit our webpage here, or to view our registered design FAQs page, please click here.

The EPO’s new Rules of Procedure of the Boards of Appeal (RPBA) came into force on 1 January 2020. Following on from our previous review examining recent case law decisions relating to changes regarding remittance, this briefing highlights two recent cases, T1625/17 and T890/17, which were decided under the new rules.

Amongst other things, the new RPBA codified a stricter approach to the ability of an appealing party to amend their case, which even prior to the new rules had already been developing in the jurisprudence of the Boards of Appeal.

As a very general summary of the new rules, in any appeal the parties must put forward their complete case at the earliest possible opportunity. New evidence and even new arguments may be ruled inadmissible by a Board of Appeal if they could have been filed earlier. Whilst a Board of Appeal does have discretion in this regard, the rules are themselves very strict, and the Boards are using their discretion to apply them strictly, as the two cases summarised below illustrate.

T1625/17

In the decision of the Board of Appeal in T1625/17, a patent proprietor had filed a series of requests for amendment of the claims (so called Auxiliary Requests), but submitted only a cursory argument as to why the amended claims were inventive. The Board of Appeal refused to consider any of these requests for amendment because the notice of appeal did not provide properly reasoned problem and solution arguments for each request.

T890/17

In T890/17, an opponent had raised an objection of lack of novelty based on a prior art document, but had mentioned inventive step only to say that if the claim was found to be novel it would be obvious. The Board found the claim novel, but refused to consider the question of inventive step because the inventive step arguments were deemed not to be properly reasoned and new arguments would not be admitted.

These decisions are not surprising, because they are in line with the new rules and with the jurisprudence which had been developing before the rules came into effect. In practice, parties must make their complete case, including properly substantiated reasoning on all foreseeable issues at the earliest possible opportunity.