In this article, which was published in Volume 12, Issue 13 of the International Pharmaceutical Industry (IPI) Journal, Mathys & Squire Partner Martin MacLean demonstrates how, following the case of Regeneron v Kymab, transgenic mice claims have been found insufficient by the Court of Appeal.

The Supreme Court judgment (24 June 2020) sends a clear “no” Brexit message to any big pharma contemplating corporate muscle-flexing of excessively broad patent claims. This ruling overturned the position held by the Court of Appeal that, for patents relating to “a principle of general application”, there was no requirement to teach how to make the full range of claimed products. In this regard, the Court of Appeal held that Regeneron’s contribution to the field extended beyond the products (transgenic mice) that could be made back in 2001, and instead related to the general principle of providing ‘better’ mice (thereby overcoming a prior art immuno-sickness problem inherent to mice transfected with human DNA). With hindsight, the Court of Appeal allowed too much weight to be given to the relative contribution the ‘better’ mice aspect provided in producing a(ny) mouse having commercial utility. In sum, the Supreme Court considered the Court of Appeal had incorrectly watered down the “sufficiency of disclosure” requirement of patent law and, in doing so, this judgment maintains a sensible balance between patent law enforceability and invalidity and provides guidance on what might constitute a ‘principle of general application’ for which broad claim scope might be held valid.

Click here to read the article in full. This provides an update to the original version, which was published in June 2020.

We are delighted to share the news of our client, Poseidon Plastics, has been awarded a £2.6 million grant from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), the national science and research funding agency, as part of its Smart Sustainable Plastic Packaging (SSPP) challenge.

The full press release is available below:

Using its proprietary technology as a platform, Poseidon’s mission is to develop a PET plastic recycling infrastructure on an industrial scale. This grant will be used to commercialise Poseidon’s scientifically proven chemical recycling technology through the construction of its first commercial facility, initially capable of processing 10kpta of waste PET. Construction is planned to start in Teesside in the second quarter of 2021 and will be completed in 2022.

The facility will redirect the equivalent of over one billion bottles per year out of landfills and the environment, to instead be repurposed into consumer packaging and other end-uses by Poseidon’s commercial partners. This facility marks the start of Poseidon’s programme to expand its chemical recycling process across the globe, rapidly expanding its output of recycled plastic feedstock, and reducing the use of PET as a ‘single-use’ plastic worldwide.

Partnering with waste collection experts Biffa Polymers, PET resin producers Alpek Polyester UK and DuPont Teijin Films UK, the University of York’s Green Chemistry Centre of Excellence and polyester fibre end-users, O’Neil’s and GRN Sportswear, Poseidon Plastics will demonstrate how previously unrecyclable post-consumer and post-industrial packaging and film, alongside other hard-to-recycle PET wastes can now be chemically recycled back to virgin-quality PET feedstock, Poseidon rBHETTM, for use in the manufacture of new consumer end-use goods.

By completing the supply chain from waste collection and sorting to feedstock production and PET manufacture through to consumer end-use goods, Poseidon and its partners will achieve a UK-first, a fully circular economy for PET plastic.

Around 80 million tonnes per annum of PET is produced globally, only a quarter of which is recycled. After the end of short first-use cycle, the majority of post-consumer and post-industrial PET plastic is currently incinerated or dumped in landfill, as it is deemed unsuitable as a feedstock for current recycling systems and processes. This is where Poseidon looks to make an immediate and significant difference; PET is lightweight, strong, inexpensive and with Poseidon’s proprietary technology, a valuable feedstock within a closed-loop circular economy.

Martin Atkins, CEO of Poseidon Plastics, commented: “We are delighted that the potential of our technology has been recognised by the government through UK Research and Innovation. This grant, as part of UKRI’s SSPP challenge, represents a significant and tangible commercial step on our way to achieving our ambitious, global-scale recycling targets.

“With the help of Alpek Polyester and our other partners, the new Teesside plant will evidence the scalability of our advanced recycling process and help us towards our core goal of making an immediate, significant, and sustainable impact on the global issue of plastic waste.”

Commenting on the news, Mathys & Squire partner Chris Hamer, who acts for Poseidon Plastics, said: “This is excellent news for Poseidon Plastics, as well as a positive step for green technology companies as the UKRI has invested a significant sum to tackle the important issue of plastic waste recycling. This would not have been possible without the specialist expertise and determination of the team at Poseidon Plastics – I look forward to seeing the construction project begin!”

On the last day of 2019, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) announced the latest amended guidelines for patent examination effective on 1 February 2020. This amendment was announced only three months after the previous amendment made in September 2019. This unusually speedy amendment to the guidelines reflects the Chinese government’s plans to strengthen the protection of IP rights in the fast-growing high-tech fields of artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain.

What’s new

A new section (Part II, Chapter Nine, Section Six, ‘the examination guidelines for inventions that contain algorithms or business rules and methods’) has been added to the guidelines. This new section aims to clarify the examination of inventions relating to AI, internet plus[1], big data and blockchain, which normally contain intellectual activities such as algorithms or business rules and methods.

The new guidelines indicate that the ‘as-a-whole’ principle for considering patentable subject matter (Article 25.1(2) and Article 2.2), as well as assessing novelty and inventive step – technical features and features relating to algorithms or business rules and methods – should not be separated in a claim. Whether a claim constitutes a technical solution should be assessed based on the technical means, the technical problem and the technical effect of the claim as a whole.

The ‘interaction-consideration’ principle for assessing inventive step is as follows: to be considered as contributing to the inventive step of a claim, features relating to algorithms or business rules and methods should be closely integrated with technical features (‘mutual supportive and interactive relations in function’) to form a technical means to solve a technical problem and result in a corresponding technical effect. Otherwise, those features relating to algorithms (in effect mathematical methods) and business rules or methods would be considered non-technical and therefore not relevant when assessing the inventive step of a claim, in a manner similar to that taken in Europe.

EPO and CNIPA new guidelines

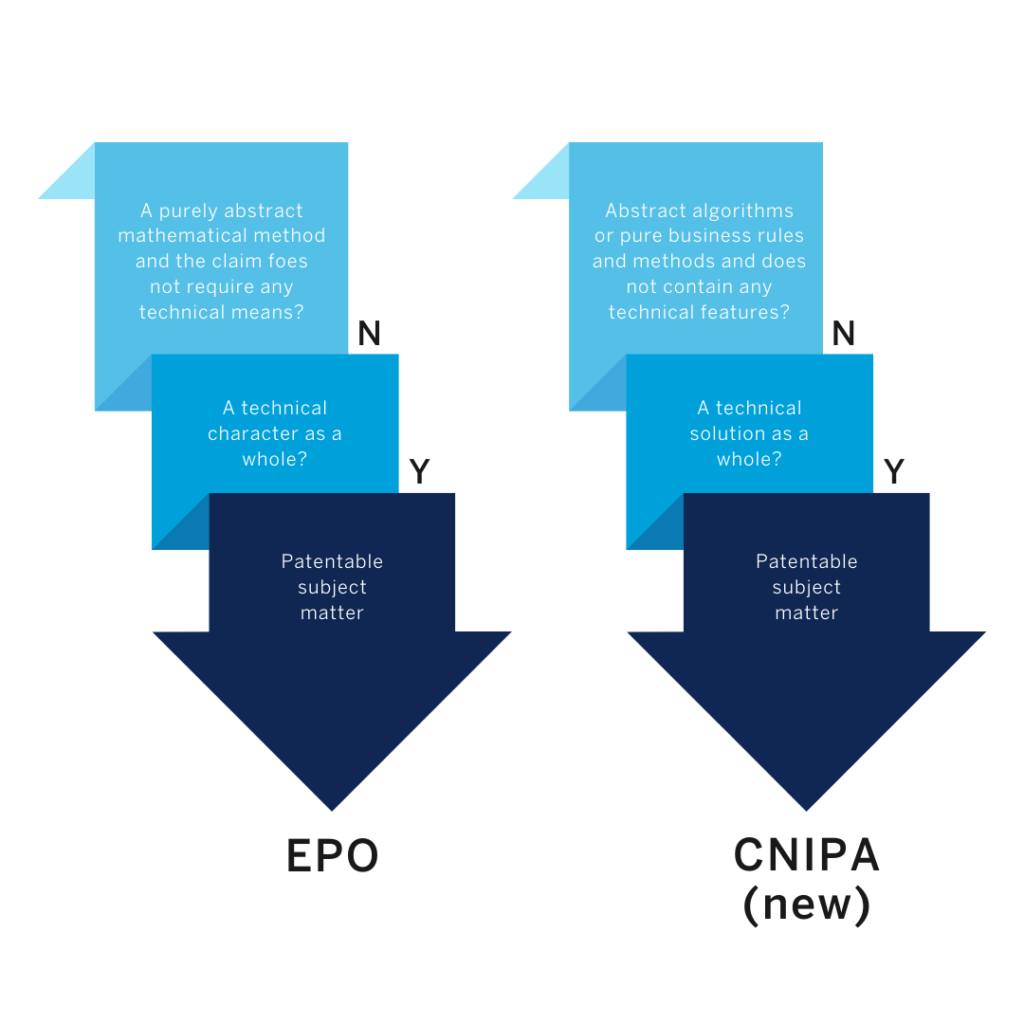

Details about the new section of the Chinese guidelines can be found in Table 1 (emphasis added) with a brief comparison between the European Patent Office (EPO) and the CNIPA guidelines.

| EPO | CNIPA (Part II, Chapter 9, Section 6x) |

| Case Law of the Boards of Appeal of the EPO, I.A.2.2.2 “The exclusion applies if a claim is directed to a purely abstract mathematical method and the claim does not require any technical means”. | 6.1.1 Examination using Article 25.1(2) “If a claim relates to an abstract algorithm or a pure business rule and method, and does not contain any technical features, the claim is excluded as a rule and a method of intellectual activity under Article 25.1(2) and shall not be granted.” |

| Guidelines G-II 3.3 “If a claim is directed either to a method involving the use of technical means (e.g. a computer) or to a device, its subject-matter has a technical character as a whole and is thus not excluded from patentability under Art. 52(2) and (3)“. Case Law of the Boards of Appeal I.D.9.1.1 “In order to be patentable, the subject-matter claimed must therefore have a “technical character” or to be more precise – involve a “technical teaching”, ie an instruction addressed to a skilled person as to how to solve a particular technical problem using particular technical means.” | 6.1.2 Examination using Article 2.2 “If a claim for protection as a whole is not excluded under Article 25.1(2) of the Patent Law, then it is necessary to examine whether it is a technical solution specified in Article 2.2 of the Patent Law. When examining whether a claim containing algorithm or business rule and method features constitutes a technical solution, it is necessary to consider all the features in the claim as a whole. If the technical means recited in the claim uses the laws of nature to solve a technical problem, and thus obtains a technical effect in conformity with the laws of nature, the solution recited in the claim is a technical solution specified in Article 2.2 of the Patent Law.” |

| GL G-VII 5.4 “When assessing the inventive step of such a mixed-type invention, all those features which contribute to the technical character of the invention are taken into account. These also include the features which, when taken in isolation, are non-technical, but do, in the context of the invention, contribute to producing a technical effect serving a technical purpose, thereby contributing to the technical character of the invention. However, features which do not contribute to the technical character of the invention cannot support the presence of an inventive step (T 641/00). Such a situation may arise, for instance, if a feature contributes only to the solution of a non-technical problem, e.g. a problem in a field excluded from patentability (see G‑II, 3 and sub-sections).” | 6.1.3 Examination on novelty and inventive step “In the examination of novelty of an invention patent application containing algorithm or business rule and method features, all the features recited in a claim shall be taken into account, and here all the features include both technical features and algorithm or business rule and method features.” “In the examination of inventive step of an invention patent application that contains both technical features and algorithm or business rule and method features, the technical features should be considered as a whole with the algorithm or business rule and method features that have mutual supportive and interactive relations in function with the technical features. “Mutual supportive and interactive relations in function” means that algorithm or business rule and method features are closely integrated with technical features to form a technical means to solve a technical problem and can obtain a corresponding technical effect. For example, if the algorithm in a claim is applied to a specific technical field and can solve a specific technical problem, then it can be considered that the algorithm features and technical features have mutual supportive and interactive relations in function, and the algorithm features become a part of the adopted technical means, in the examination of inventive step the contribution of the algorithm features to the technical solution should be considered. In another example, if the implementation of business rule and method features in a claim requires an adjustment or an improvement of technical means, then business rule and method features and technical features could be considered to have mutual supportive and interactive relations in function, and in the examination of inventive step the contribution of business rule and method features to the technical solution should be considered. |

CNIPA examples

Section 6.2 provides 10 examples illustrating the application of the new guidelines in various scenarios from both positive and negative aspects. Examples 1 to 6 demonstrate whether the subject matter in the claimed invention is patentable. Example 1 relates to a method for establishing an abstract mathematical model, which should be excluded from patentability under Article 25.1(2). Examples 2 to 6 discuss what constitutes a technical solution in the fields of AI, business models and blockchain specified in Article 2.2 of the guidelines.

For instance, example 4 describes a method for preventing blockchain business nodes from leaking user privacy data in the alliance chain network. This claimed invention addresses a technical problem of providing more secure blockchain data – business nodes only establish connections to limited objects, by carrying the Certificate Authority (CA) certificate in the communication request and configuring the CA trust list in advance to determine whether to establish a connection. Such technical means achieve the technical effect of securing communications between business nodes and reducing the possibility of business nodes leaking private data. Therefore, the solution in this example is a technical solution specified in Article 2.2.

In contrast, example 5 relates to a method for promoting users’ consumption. This method, however, does not constitute a technical problem because a computer is only executed to determine the rebate amount based on the user’s consumption amount according to the specified rules. Therefore, in this application, no technical means are used, and the only effect of this claimed invention is to promote users’ consumption. The subject-matter in this patent application thus is excluded from patentability.

Examples 7 to 10 demonstrate whether the subject matter in patent applications involves an inventive step, which will be compared with EPO’s examples in a later section.

| Section | Title |

| 6.1.1 Article 25.1(2) An abstract algorithm or a pure business rule and method? | Ex. 1 – A method for establishing a mathematical model |

| 6.1.2 Article 2.2 A technical solution? | Ex. 2 – A method for training a convolutional neural network model Ex. 3 – A method for using shared bicycles Ex. 4 – A communication method and device between blockchain nodes Ex. 5 – A method of consumption rebate Ex. 6 – A method for analysing an economic sentiment index based on electricity consumption characteristics |

| 6.1.3 Novelty and inventive step | Ex. 7 – A method for detecting the falling state of a humanoid robot based on multi-sensor information Ex. 9 – A method of logistics distribution Ex. 8 – A multi-robot path planning system based on a cooperative co-evolution and multi-group genetic algorithm Ex. 10 – A method for visualising the evolution of dynamic viewpoints |

EPO v CNIPA – patentable subject matter

For the purposes of comparison, these new guidelines (section 6.1.1 and section 6.1.2) relating to patentable subject matter appear to be close to the EPO’s approach (as compared in the following Figure 1 and in the previous Table 1).

EPO v CNIPA – inventive step

The EPO guidelines (GL G-VII 5.4) and the case law (T 641/00) distinguish between three groups of features:

i) technical features,

ii) non-technical features, and

iii) features which, when taken in isolation, are non-technical, but do, in the context of the invention, contribute to producing a technical effect serving a technical purpose, thereby contributing to the technical character of the invention.

When following the approach set out in the new Chinese guidelines for assessing inventive step (section 6.1.3), algorithm or business rule and method features may be equivalent to the features in the EPO’s group iii. It might be worth noting that the CNIPA currently only considers these two particular kinds of ‘non-technical’ features (i.e. algorithms or business rule and method features) to be able to contribute to inventive step. The CNIPA’s approach seemingly first considers whether algorithm or business rule and method features and more traditional ‘technical features’ interact with each other functionally in the context of the invention to solve a technical problem and result in a corresponding technical effect. If yes, then the contribution of algorithm or business rule and method features should be considered.

| EPO examples (inventive step) |

| 5.4.2.1 Example 1 – Method of facilitating shopping on a mobile device |

| 5.4.2.2 Example 2 – A computer-implemented method for brokering offers and demands in the field of transporting freight |

| 5.4.2.3 Example 3 – A system for the transmission of a broadcast media channel to a remote client over a data connection |

| 5.4.2.4 Example 4 – A computer-implemented method for the numerical simulation of the performance of an electronic circuit subject to 1/f noise |

Two CNIPA examples (example 7* and example 10** detailed in post-script) and two EPO examples (5.4.2.2 example 2 and 5.4.2.4 example 4) are selected to demonstrate whether technical features and algorithm or business rule and method features interact with each other functionally in the context of the invention.

In example 7, it is considered that algorithm features – i.e. the fuzzy algorithm in step (2) – are closely integrated with technical features (i.e. the robot information in step (1)), because the input parameters of the fuzzy algorithm are limited to the robot information to determine the stability state of the humanoid robot. In one EPO example (5.4.2.4 example 4), ‘the mathematically expressed claim features’ when considered in isolation, represent a mathematical method with no technical character. However, these features contribute to the technical character of the method because the claim is limited to a computer-implemented method in which this mathematical method serves a technical purpose of ‘circuit simulation’. In other words, the ‘mathematically expressed claim features’ and the technical features of ‘circuit simulation’ can be considered to interact with each other functionally in the context of the invention.

In example 10, the CNIPA explains that the technical means for visualisation could be used with different sentiment categorisation rules (the algorithm feature). Therefore, the sentiment categorisation rule and the visualisation method do not interact with each other functionally. Similarly, the EPO provides an example in its guidelines (5.4.2.2 example 2) in which the features defining a business method were ‘easily separable’ from the technical features of its computer implementation. Thus, the business method features and technical features cannot be considered to interact with each other functionally in the context of the invention.

Conclusion

To conclude, the new CNIPA guidelines bring some welcome clarity to what was a grey area of determining the patentability of an application involving business rules and methods, algorithms and mathematical methods. Previously, it was very common to see Chinese Examiners assessing inventive step based on divided features in a claim, and there was no clear guidance on how to examine ‘non-technical’ features. The new guidelines, therefore, tend to be more friendly to patent applicants because of the new ‘as-a-whole’ principle and the ‘interaction-consideration’ principle. This fast-track amendment indicates that, in order to keep up with the times, the CNIPA is maintaining a positive attitude towards AI and blockchain-related inventions.

Post-script

Example 7 *

Claim 1 recites

“A method for detecting the falling state of a humanoid robot based on multi-sensor information, which is characterized by the following steps:

(1) fusing attitude sensor information, zero-moment point ZMP sensor information and robot walking stage information to establish a sensor information fusion model with a layered structure;

(2) using the front and rear fuzzy decision system and the left and right fuzzy decision system to determine the stability of the robot in the front and rear direction, and the left and right direction respectively, the specific steps are as follows:

① determining the walking stage of the robot according to the contact between the robot support foot and the ground and offline gait planning;

②applying fuzzy inference algorithm on the position information of ZMP;

③applying fuzzy inference algorithm on the pitch or roll angle of the robot;

④ determining the output membership function;

⑤ determining fuzzy inference rules according to steps ①~④;

⑥ de-fuzzifying.“

D1 is considered as the closest art and discloses step (1) of the method. Therefore, the difference between D1 lies in step (2) – i.e. implementation of the fuzzy decision algorithm. Compared to D1, the technical problem solved by the claimed invention is how to determine the stability state of the robot and accurately predict its possible fall direction. The altitude information, ZMP (Zero Moment Point) position information and walking stage information in step (1) are used as input parameters, and the fuzzy algorithm in step (2) outputs information to determine the stability state of the humanoid robot, which provides a basis for further accurate posture adjustment instructions. Therefore, the algorithm features and technical features have mutual supportive and interactive relations in function, and they are closely integrated and jointly constitute a technical means to solve a technical problem and thus obtain a corresponding technical effect.

Example 10 **

Claim 1 recites

“A method for visualising the evolution of dynamic viewpoints, comprising:

Step 1 – a computing device determines a sentiment membership and sentiment category of the information in the collected information set, the sentiment membership of the information indicates how likely the information belongs to a sentiment category;

Step 2 – the sentiment category is positive, neutral, or negative, the specific categorisation method is: If the value r of the number of likes p divided by the number of dislikes q is greater than the threshold value a, then the sentiment category is considered as positive, if the value r is less than the threshold b, then the sentiment category is considered as negative, if b≤r≤a, then the sentiment category is neutral, wherein a>b;

Step 3 – based on the sentiment category of the information, the geometric layout of the sentiment visualisation of the information set is automatically established, the horizontal axis represents the time of information generation, and the vertical axis represents the amount of information belonging to each sentiment category;

Step 4 – the computing device colours the established geometric layout based on the sentiment membership of the information, and colours the information on each sentiment category layer according to the gradual order of the information colour.”

D1 discloses a sentiment-based visualisation analysis method, where time is represented as a horizontal axis, the width of each colour band represents a measure of sentiment at that time, and different colour bands represent different sentiment.

The difference between the solution of the claimed invention and the closest prior art D1 is the new sentiment categorisation rule proposed in step 2. It should be noted that the same technical means for colouring could be used with different sentiment categorisation rules. Therefore, the sentiment categorisation rule and the visualisation method do not have mutual supportive and interactive relations in function.

In addition, the problem of ‘visualisation’ has been solved in D1. Compared to D1, the claimed invention only proposes a new rule for sentiment categorisation, which does not actually solve any technical problem or make a technical contribution to the art. Consequently, the claimed technical solution of the claimed invention does not involve an inventive step in light of D1.

[1] Similar to Information Superhighway and Industry 4.0, the Chinese government has created its own “Internet Plus” initiative to transform, modernize and equip traditional industries to join the modern economy.

In its recent decision, the EUIPO Fourth Board of Appeal overturned the Opposition Division’s earlier decision in opposition proceedings concerning ex-professional footballer Jürgen Klinsmann and Panini Societá Per Azioni (‘Panini’), which is perhaps best known for producing collectable stickers of footballers and sticker albums.

The marks

The case concerned Mr Klinsmann’s EU designation of international registration no. 1384372 for the above mark for a range of goods in classes 16. 25 and 32 (including printed matter, clothing and beers and non-alcoholic beverages, respectively) and services in class 41 (including sporting activities). Panini opposed the designation on the basis of the following marks:

1. Italian reg. no. 1539690 for services in class 41 (including sporting activities);

2. EU designation of international reg. no. 1282870 for goods in class 32 (including beers and non-alcoholic beverages);

3. Italian reg. no. 1561953 for goods in classes 16 and 25 (including stickers and clothing articles, respectively);

4. Italian reg. no. 1063937 (representation of mark not provided) for goods in classes 16 and 25 (including stickers and clothing articles, respectively);

5. EU reg. no. 4244273 for goods in class 16 (including stickers); and

6. EU reg. no. 4244265 for goods in class 16 (including stickers).

The opposition proceedings

Grounds 1-4 were based on the allegation of a likelihood of confusion between those marks and Mr Klinsmann’s. Grounds 5 and 6 were based on Panini’s alleged reputation in those marks and the allegation that Mr Klinsmann’s use of his mark would take unfair advantage of, or cause detriment to, that reputation.

The Opposition Division found a likelihood of confusion in respect of grounds 1, 2 and 3 and therefore refused the application for all of the contested goods/services and did not proceed to examine the opposition under grounds 5 and 6.

Mr Klinsmann appealed the decision asserting that the marks are dissimilar.

The appeal proceedings

The Board of Appeal found that the respective marks were, as Mr Klinsmann alleged, dissimilar on the basis that Mr Klinsmann’s mark differs from Panini’s marks in that:

- it only consists of a black and white sketch without any contours within the sign itself, which is just black;

- there is a circle around the black sketchy element;

- the silhouette is markedly different in position and direction (the thickest stroke being vertical upwards).

The Board found that “the impression of both marks as a whole is markedly different. There is not even one single ‘element’ that could be singled out from the earlier mark and then be found to ‘match’”. In the absence of any word element, no oral assessment could be performed.

The Board also continued that “the representation of a football player, as a concept, is weak for goods that have to do with football and sports in general. That extends to ‘clothing’ insofar as sportive clothing is covered, and to Class 16 as regards the goods for which the opponent claims an actual use (and reputation), namely stickers of footballers and football books, almanacs or albums”. It found that Mr Klinsmann’s mark would not be perceived unambiguously as a football player, and therefore has no clear concept; as a result there was no conceptual similarity between the marks.

As the Board found that the marks were visually and conceptually dissimilar, it could not find a likelihood of confusion or unfair advantage/detriment. Particularly noteworthy is the fact that, as Panini failed to file adequate proof of use of the mark under ground 6 (which it was requested to do by Mr Klinsmann), the opposition was unfounded in that regard. The same was true for the mark under ground 4.

Commenting on the decision, Harry Rowe, managing associate in the Mathys & Squire trade mark team, said: “As a Tottenham Hotspur fan (Klinsmann being a club legend) and a lover of all things trade marks, this case particularly piqued my interest. The case represents an important example of the narrower scope of protection afforded to figurative marks (as compared to word marks); it shows that one cannot merely rely on slight visual and conceptual similarities for a successful opposition. It also highlights the importance of filing cogent evidence of use (and the need to keep records of such evidence in the event it is required in opposition or cancellation proceedings).”

A version of this article was published in The Trademark Lawyer magazine in October 2020.

In this article for Intellectual Property Magazine, partner Andrew White discusses how the automotive ‘patent battles’ are heating up in light of the Nokia dispute.

The automotive standards essential patents (SEPs) wars are heating up. The decision of the Mannheim regional court in Germany, which was announced on 18 August 2020, secured a win for Nokia against the Mercedes carmaker Daimler, but many questions still remain. In particular, it is still not clear whether Tier 1 suppliers are required to be the licencees of any relevant SEPs or whether it is the carmakers themselves.

The decision related to only one of 10 connected suits filed by Nokia against Daimler, and the litigation has garnered much attention from other car makers, suppliers and even politicians. While the eye-wateringly high bond of €7bn required by Nokia to obtain an injunction against Daimler is very high, Nokia claims it will help bring Daimler back to the negotiating table. The decision itself also raises questions as to the conduct of the patent holder (Nokia), and it is expected that if Daimler is to appeal the decision, clarification would be sought from the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

This article was originally published in Intellectual Property Magazine in October 2020 – click here to read the full version (login required).

In this article for The Patent Lawyer, partners Sean Leach and Andrew White lay out a general roadmap to help non-European practitioners navigate the landscape.

Partners Sean Leach, Andrew White and Juliet Redhouse have hosted a webinar on this topic – click here to download a recording.

A patent or patent application in the hands of a third-party, which covers a product which you wish to exploit presents a difficult challenge, and even more so if it is in a foreign jurisdiction. Preliminary qualitative research indicates that, in the US at least, the options to monitor and mitigate risks from European patents are not widely known. All but the most internationally focused US and Chinese attorneys use the European procedures infrequently, and their clients even less so.

Whether defending patent infringement action, reducing the risk posed by such actions, applying for complete or partial revocation of a patent, or opposing grant of a problem patent in the first place European jurisdictions offer many effective options, which by comparison with similar measures in the US are low-cost, low-risk and procedurally simple. Much can be done anonymously, and there are very good tactical reasons to take advantage of the possibility to remain anonymous.

In addition to these helpful features of the European procedural and legal landscape there are other issues, such as bifurcation in Germany and the losing party’s liability for the other side’s legal costs, which can represent very significant risks in their own right.

The background – patents granted by the EPO

The EPO provides a centralised examination procedure, through which a single application granted by the EPO is turned into a bundle of independent national patents.

Each patent must be dealt with separately after grant in the courts of each relevant national jurisdiction. Complete revocation of a granted European patent may thus require court proceedings in multiple jurisdictions, each conducted in a different language, under different evidential and procedural standards.

To a third-party to whom a European patent presents a risk, it is thus far better to take action at the EPO when possible. This can be done by filing so called “observations”, or by filing an opposition within a nine month time window after grant to have the patent revoked centrally at the EPO. Both can be done anonymously, which conveys a very significant tactical benefit because arguments can be advanced without constraining the conduct of future proceedings and because a patent proprietor forced to amend by an anonymous opponent cannot know the infringement target which they are aiming to hit.

In EPO proceedings there is no discovery or disclosure obligation on the parties, and only a very limited liability for the other side’s costs. There is no estoppel, the quality of the decisions is high and the rules of evidence and the standards applied by the EPO mean that outcomes are, by comparison to national proceedings, straightforward, fast and predictable.

1. Before grant: the options to attack an EPO or national application prior to grant in Europe

So-called “third-party observations” can be filed anonymously at the EPO at any point until the patent grants (and can even be filed against PCT applications before they enter the European Regional Phase).

The best time to file third party observations is thus early in examination before minds have been made up, and so the Examiner will be obliged to take them into account (the EPO Guidelines state that if the observations call into question the patentability of the invention in whole or in part, they must be taken into account). Experience suggests that unless the issue of patentability is prima facie clear, the observations may be less effective than one might hope. On the other hand, if the observations are fully substantiated and filed prior to any communication of intended grant, the EPO will normally issue a new office action within three months of their receipt.

The objections likely to fare best are clear added matter objections and clear novelty objections. Importantly, in Europe there is generally no presumption of validity. This is significant because a document being cited during prosecution does not mean that a national court will presume that a patent is valid over that document.

A potential downside to third party observations is that the applicant may amend the patent application so as to strengthen it. Thus there may be attacks which could be made but which would be much better saved for an Opposition (see below). However, an applicant responding to anonymous observations does not have any infringement target in mind. It may thus be possible, by carefully calibrated attacks, to shepherd an applicant toward a desirable amendment to clear a product without them ever having been aware of it.

2. Post-grant: the EPO opposition procedure, and its German national equivalent

As noted above, once a European patent application grants, it is converted into national rights, and litigation must be done at a national level at national courts. This can rapidly become expensive. One tactic adopted by some is to litigate in a single territory first and use the outcome of that litigating to force mediation/an agreement elsewhere. However, even adopting such a tactic, costs will be higher. For example, the cost of patent litigation in the English courts (even via the relatively cheaper Intellectual Property Enterprise Court) is typically measured in multiples of hundreds of thousands of pounds with further costs if there is an appeal.

By comparison, the cost of most EPO oppositions is generally less than £100K in all but the most complex cases, and simple cases can be won for far less. At the time of writing this article, an opposition (including detailed professional searches for prior art) could be concluded for about £30K-70K, and takes around two to four years to complete. Normally, first instance proceedings culminate in an in-person hearing at the EPO. An opposition decision can be appealed, which can add another two to four years and further cost – although appeals can be accelerated.

The EPO issues on average around 2000 opposition decisions a year, and roughly 30% result in the patent being upheld as granted, about 30% result in the patent being revoked, with the remaining 40% resulting in the patent being maintained in amended form. Therefore, opposition proceedings represent a good prospect of having the scope of a granted patent changed in some form or other.

To take advantage of the Opposition procedure it is of course necessary to be aware of the patent within the nine month Opposition period. Only during this window of opportunity can the patent be challenged centrally at the EPO. It is therefore prudent to search for competitors’ patent applications at the EPO and to monitor their progress. If the Opposition window is missed it cannot be reopened.

3. Post-grant: the options to control risk from national patents after grant and EP patents outside the EPO opposition period

a. UKIPO infringement and validity opinions

If the opposition period has been missed, or if it simply isn’t relevant (e.g. the patent was filed directly in a selected number of European territories) there are still options available to challenge and cast doubt on the validity of granted patents in Europe without costly court proceedings.

In the UK it is possible to obtain an opinion from the UKIPO either relating to the validity of the patent and/or as regards infringement. Opinions are fast and low cost and can be used to influence the conduct of later proceedings, and may have implications for awards of costs. Opinions can be requested anonymously.

UKIPO validity opinions are limited to issues of novelty and inventive step. The official fee is around £200 and the request can be filed against any patent or SPC, even if it is no longer in force. A list of opinions issued last year can be found here. The patentee is given an opportunity to comment, and the UKIPO will normally issue a validity opinion within three months. The opinion is non-binding, but the UKIPO can revoke a patent in cases where the patent is clearly invalid. This is rare. The procedure for obtaining an opinion on validity is relatively new, and to date 90 opinions have been issued, with 43 finding the patent to be invalid. Only 36 final decisions have been issued, with about half resulting in the patent being amended. In six cases the patent has been revoked.

Infringement opinions follow similar procedure and are also non-binding, but may serve as a useful negotiation tool to avoid or resolve a potential dispute.

b. Revocation actions in the national courts & before the UKIPO

In the UK, a revocation action can be taken before the UKIPO or the courts (The Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC) or the High Court (Patents Court)). The action can be raised on essentially the same grounds as for an EPO opposition. If action is taken before the UKIPO, a typical timeframe may be between 6 months to a year. Notably, decisions from the UKIPO can be appealed to the Patents Court. While a revocation action cannot be filed anonymously, any individual or legal entity can apply for revocation and (unlike e.g. in the US), there is no requirement for any threatened or actual proceedings.

If action is taken before the IPEC or Patents Court, it would probably take around 12 months to go to trial. Notably an application for revocation can be stayed pending the outcome of any pending EPO opposition proceedings.

The costs of the proceedings will be determined by the complexity of the case but may typically be in the range of £10,000 to £30,000 before the UK IPO, £50,000 to £200,000 before IPEC and £250,000 to £1,000,000 or even higher before the Patents Court. In English litigation, the losing party generally has to pay the other side’s costs. While costs are limited before the UKIPO and IPEC (in the IPEC the costs are capped at £50,000), in the Patents Court there is no limit on the award of costs

Whilst the procedure before the courts of each jurisdiction is independent, and courts in different European countries do sometimes reach different conclusions on the same patents, a successful outcome from the court of a major jurisdiction is likely to at least influence proceedings in other territories.

c. Bifurcation and protective briefs in Germany

In Germany validity and infringement are dealt with separately (in so-called bifurcated proceedings). It is thus possible for a patentee to obtain a preliminary injunction very quickly and without any invalidity defence even being considered.

To defend against this risk a protective brief can be filed pre-emptively at a German court setting out arguments against infringement or validity of the patent concerned. It is only disclosed to the patentee if they apply for a preliminary injunction. The benefit of a protective brief is that it ensures an invalidity defence must be addressed by the patentee and considered by the court before a preliminary injunction can be issued.

Conclusion

We have had a series of conversations with non-European attorneys to understand their view of European patent risk. The conclusion we drew from those conversations is that the monitoring and watching that most European attorneys do for their clients is not adopted as widely outside Europe as it could be. When faced with a European patent or patent application which presents a risk, forewarned is most certainly forearmed. The EPO opposition procedure is predictable, fast, and low cost. More people should use it. Although such action before the EPO has much to recommend it, there are also a range of options available in national jurisdictions to control risk without launching revocation proceedings as a first resort.

This article was first published in the Sept/Oct 2020 edition of The Patent Lawyer (pp. 76-79).

With antibodies accounting for seven out of the top ten global drugs¹, it is of critical importance that those companies that invest huge sums of money into R&D in this technology space are able to protect their investment from unlawful competition. Whilst the patent system provides a pretty good framework for achieving this, the approaches taken by patent offices in different parts of the world can vary widely, potentially impacting one’s ability to secure optimal patent protection (in terms of territorial scope and/or patent claim scope). Unsurprisingly, therefore, the risk of failing to achieve commercially viable patent protection in a key jurisdiction (plus loss of an important revenue stream) provides a strong incentive to operate at the highest possible patentability threshold. Here, we will focus on the European Patent Office (EPO), and on the key issues you will likely need to address in order to obtain patent protection in Europe for a new antibody therapeutic.

Obtaining Patent Protection for Antibody Subject-matter at the EPO

For antibodies directed at a new target, such as a new antigen structure that has not been targeted before, it may be possible to obtain broad patent protection at the EPO for antibodies that bind specifically to that target. However, these broad patents are becoming less common because it is now unusual to discover such a new target. Most antibody patents, therefore, relate to antibodies that bind to a known target, and where other antibodies binding to the same target have been described.

The EPO allows the patenting of new antibodies, but only when said antibodies also demonstrate an unexpected technical effect (i.e. an inventive step) when compared to antibodies that were known before. Unlike some patent offices around the world, which may concede that a new antibody is inventive because of a unique structure or sequence it possesses when compared with previously known antibodies, a difference in structure or sequence alone is not enough to establish inventive step at the EPO. Moreover, this remains the case irrespective of whether said unique structure or sequence maps to the framework regions or to the complementary determining regions (CDRs) of the antibody. Thus, a new antibody against a known target will only be considered inventive by the EPO if it shows an unexpected property, or if it was unexpected that such an antibody could be produced at all.

A key component of the EPO’s reasoning is that many techniques in the field of antibody production are routine, and that antibodies against a given target can be produced in large numbers without any inventive input being needed. For example, the EPO considers it routine to immunise animals with an antigen, to obtain a large number of different antibodies against that antigen that are produced by the animals, and to screen the resulting antibodies to confirm binding to the antigen of interest. Because the generation of antibodies in such immunisation methods is essentially random, the EPO assumes that essentially all antibodies against that antigen could be found eventually by just routine trial and error experiments, given a sufficient amount of time and resources. As a starting point, therefore, the EPO will assume that any antibody that has been produced against a known target could have been found in a routine way, and so is not inventive. Thus, the burden lies with the applicant of a patent application to convince the EPO otherwise.

The EPO also considers that other techniques in the antibody field, such as humanisation and affinity maturation, are now routine, and again that trial and error would eventually produce any effective humanised or affinity matured variants of a starting antibody. This suggests that over time, it may become increasingly difficult to persuade the EPO that antibody claims are inventive, as more techniques for antibody production, optimisation and selection become routine in the field. Thus, for new antibodies that bind to a known target (particularly if other antibodies against that target are known), the applicant must demonstrate there is something that makes said antibodies surprisingly better than other antibodies that were known to bind to the same antigen (else surprisingly better than would have been expected based on what was known about the target antigen and corresponding antibodies).

In theory, any kind of advantage can be relied upon. For example, this might relate to the way that the antibody binds to its target, such as improved specificity, cross-reactivity, or affinity; it might relate to improved properties of the antibody in vivo or in vitro, such as improved pharmacokinetic properties, low immunogenicity, or improved biological activity; or it might be based on other properties of the antibody which do not relate directly to its binding properties, such as improved storage stability, improved formulation properties or improved expression levels.

In practice, any advantage relied on must be surprising in its own context. For example, for a humanised antibody, the EPO might reasonably expect that it will have reduced immunogenicity compared to an antibody that is not humanised, so such a technical effect alone is unlikely to be enough to confer an inventive step. However, if a humanised antibody were to retain a high affinity for its target antigen, this might reasonably be considered surprising and thus supportive of an inventive step. Conversely, if an asserted technical effect is found to be unsurprising, then it is unlikely the EPO will allow any patent claim to the antibody, irrespective of whether the antibody in question is defined by reference to all six CDR sequences, both variable domain sequences, or even the full amino acid sequence of the antibody molecule. In such scenarios, even a very narrow “picture” claim is unlikely to be awarded.

Having established the presence of an unexpected technical effect (and thus inventive step), the next question to be considered by the EPO is that of claim scope. Namely, how broad can I claim variants of the antibody?

This assessment flows from analysis of the scientific principles that underpin the asserted unexpected technical effect, and attempts to ensure that the scope of patent claim awarded is commensurate with the level of scientific contribution the invention provides above and beyond the prior art. To put this another way, the EPO’s general approach is the unexpected technical effect relied on to support inventive step must be demonstrated across the full scope of the awarded patent claims. In more detail, it must be at least technically credible that all the antibodies across the scope of your defined claims demonstrate the same unexpected technical effect / advantage. The EPO’s analysis will, therefore, involve considering the properties or features of your antibody that are responsible for that advantage.

For example, you may be able to establish that your antibody is inventive because it has particular binding selectivity for one antigen and not to another. If your inventive step is based on the binding specificity or selectivity of your antibody, then the EPO is likely to take the view that the advantage might reasonably be shared by other antibodies that have the same set of six CDRs, or both variable domain sequences of your antibody. For this type of advantage, the EPO will, therefore, usually insist that you limit your patent claims to antibodies that include all six CDR sequences, or both variable domain sequences, of your antibody. It can be possible to obtain broader protection than this, but to do so, it is likely that you will need evidence that the same advantage is also found for other antibodies that do not have these particular sets of sequences. For example, to obtain a patent that does not require all six CDR sequences to be present, you might need data showing that antibodies with fewer than six CDRs, or antibodies having particular variations in the CDR sequences, will retain the same inventive advantage. The scope of patent claims that you will obtain will depend upon the related antibody sequences that you can persuade the EPO will retain the inventive advantage.

Another common advantage that is used to establish an inventive step at the EPO is improved affinity. The EPO considers that the choice of framework regions, as well as the CDR sequences themselves, may considerably influence antibody affinity. This means that if inventive step is based solely on an antibody having improved affinity for a target, then the EPO is likely to require the framework regions and the CDR sequences to be defined in the patent claim. In practice, this means that you will be asked to limit your patent claims to antibodies having the same heavy and light chain variable region sequences as your antibody. Again, if you wish to obtain broader patent scope, then it is likely that the EPO will require supporting evidence that the improved affinity would be retained with other framework.

The same principles will be applied by the EPO to any advantage that you are relying upon to obtain an inventive step. If the advantage is linked to a particular structure or feature of your antibody, then the EPO is likely to require that structure or feature to be defined in the claims. For example, if your advantage relates to improved effector functions, then the EPO may require particular Fe domain sequences to be recited in the claims. If the advantage relates to a physical property of the antibody, such as its stability or production yield, then the EPO may consider that to be a property of the molecule as a whole, and so require the full antibody sequences to be defined in the claims.

If you need to rely on a technical advantage over other antibodies, then how can you establish that such an advantage exists, and when do you need to provide that information? The EPO considers that it must be derivable from your original patent application that the invention had been made before that application was filed. This does not mean that your patent application needs to provide absolute proof of the advantage. Indeed, it may not be possible to include the ideal comparisons in your application to prove that an advantage exists. For example, the EPO requires that an inventive step is established when compared to what it considers to be the “closest prior art”. In this field, that is likely to be an earlier antibody that binds to the same antigen and that has similar properties. However, you may not know at the time of the patent application being filed what other antibodies may exist to the same target, and you may not be able to determine which antibody the EPO will later consider to be the “closest”. Even if you are aware of earlier publications describing other antibodies, those antibodies may not be publicly available, and so it may not be possible to carry out any direct comparison in order to confirm that an advantage exists.

What the EPO will look for in the patent application is enough information to make it technically plausible that the advantage would be achieved. Your patent application might include data demonstrating particular effects or measuring particular parameters for your antibody, and might, therefore, provide data that could be used for a subsequent comparison with other antibodies, or it might include technical reasons why an effect or advantage can be plausibly derived from the available data.

If you can meet this threshold and persuade the EPO that your advantage was technically plausible from the information in your original patent application, then you may be permitted to rely on additional evidence, not included in the original patent application, to confirm the existence of the advantage. For example, you may be able to submit in vivo data confirming effects that were shown in vitro, or you may be able to submit comparative data confirming that your antibody does show an improvement when compared to particular antibodies that the EPO has selected as the “closest”.

In conclusion, the EPO takes a technical and scientific approach when considering inventions in the antibody field. Every case will be judged on its own facts, but in general, the EPO will start from a number of preconceptions about what could have been done in a routine way, and the burden is likely on you to counter those preconceptions in order to persuade the EPO that your antibody is inventive.

An antibody that is new, and that is effective at binding its desired target, is unlikely to be considered inventive by the EPO unless it also exhibits some kind of unexpected technical effect (e.g. an advantage) when compared to other antibodies against the same target. This is worth considering when you draft a new patent application in this field. Ideally, your patent application will include some data supporting the superior properties of your antibody, or it will at least include a technical rationale to make it credible that your antibody has such an advantage. You should also consider the scope of claim that the EPO is likely to allow based on the advantages that you can establish. If you want to obtain broader claims than are likely to be allowed by default, then you may need to obtain more data before filing the application, to show that your advantage can be obtained with a broader range of antibodies than might otherwise be expected. Most importantly, when preparing a patent specification, you should think ahead to present a tiered range of (plausible) technical effects that may be relied on to provide potential fallback positions during prosecution and beyond.

This article was originally published in the International Biopharmaceutical Industry Journal.

1. Urquhart (2020) Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 19: 228

Fintech places particular demands on high frequency computing (HPC) that requires significant investment into computing resources such as CPU and GPU, in addition to the requirements of data scientists’ and quants’ time to maintain a complex and ever-evolving code base. New, more effective solutions are required as sophistication of regulations and increased risks grow.

Machine learning (ML) is also increasing in prevalence. In so-called supervised learning, ML models are trained on input data sets that have known outcomes; they are then able to ‘learn’ from these and predict outcomes for new input data sets.

The intellectual property (IP) in such techniques is of enormous value. Over the last few years, there have been significant changes in the legal landscape, both in terms of trade secrets protection and what is eligible for patent protection in major jurisdictions. More changes are coming. This article explains some of the challenges surrounding IP in this area and gives practical direction in how to approach the issue.

Changes in the legal landscape – risks and mitigations

The main patent granting authority for Europe (the EPO) is preparing to issue a landmark decision on the granting of patents for the computational techniques used for ML and the modelling of complex systems. There is justifiable speculation that that decision will herald a more liberal approach to the granting of patents in this area – many of which may have clear relevance to the fintech sector. This is important and financial institutions should take note.

Patent infringement represents a very significant hazard. For an infringer in financial services, the cost of paying damages to the patent holder could be just one of the problems they face because a patent holder may obtain an injunction overnight to prevent use of a patented technology. The infringer may thus be forced to withdraw service from a client immediately. If such sudden disruption of service causes consequential losses for the client, the infringer may be liable to their client for those losses. This is to say nothing of the damage to the client relationship, and the not insignificant financial cost and reputational damage of being found to have infringed a patent.

Patents are unique amongst IP rights in the fintech space. Confidential information and trade secrets in Europe only provide a private contractual right against those who have agreed to confidentiality. Copyright is a little broader, but direct or indirect copying must be proven if copyright is to be enforced. Neither copyright nor trade secrets offer any protection outside these limited bounds. Patents on the other hand can be enforced against anyone who uses a technology, regardless if they learned it honestly or created it independently themselves.

This poses a problem: how can fintech innovators protect themselves against patent risk?

Help is at hand: the strategies that have been used in other fields of engineering for decades can be applied directly to fintech. Innovators must conduct sensible patents searches to identify the most likely risks. If found early, problem patents can be opposed at the EPO before they come into force, because defending against them later is at least two orders of magnitude costlier and riskier. This cannot catch everything however, so the most widely used strategy for controlling risk from third party patents is to secure patents of one’s own. The aim of this ‘defensive strategy’ is that one’s own patents present a risk to the competition, or at least cover desirable technology. A competitor who knows they might themselves infringe a patent is unlikely to assert their own patents against the holder of that patent. This strategy has kept the peace in the telecoms and electronics industries for generations, and a leading patents judge once described it as “the only rational way to use the patent system”. What makes the ‘smartphone wars’ newsworthy is that they buck this decades’ long trend.

Case study

Dmitri Golubentsev is the founder of Matlogica, a young fintech startup offering a niche proposition for large financial organisations focused on improving risk management capabilities in terms of performance and cost effectiveness. As a challenger startup, Dmitri says he has proven that the technology their competitors do not believe is possible brings demonstrated and significant performance improvements.

Technology designed to improve performance of applications built using high-level, object-oriented languages has always been challenging to protect with patents. However, Matlogica’s approach works by breaking down and rebuilding the primal code into a recorded function, which is thread safe and can be safely executed on multicore systems. This provides a technical benefit which is the basis of patentable technology.

A complete strategy

There is more to life than patents. Any business operates in a landscape of commercial relationships. The IP and trade secret issues which arise in that landscape just add a further dimension to the existing considerations

in managing those relationships. Other factors may be more or less important at different stages, but taking careful and measured steps at the right time can increase leverage and achieve significant market impact. These steps can be as simple as just ensuring sensitive information is handled properly; ensuring that agreements with development partners are properly drafted and address the key IP issues; or identifying patentable inventions and choosing when to protect them.

Asked to comment for this article, Dmitri said: “Although we are now publicly recognised by leading experts as a breakthrough technology, it is natural to expect some friction during our business’ first steps. By investing in IP, we are not only reducing our barrier for entry, but also increasing chances for partnerships with established vendors. Our patent and IP position allows us to approach a wide range of potential clients, partners and competitors without risk of the technology being easily copied.”

It is common for fintech businesses to overlook these questions, or assume that technology is not patentable, or that questions of ownership can be dealt with once the value in a technology has been demonstrated. Experience shows that this is not the right approach: the value of simple steps done early cannot be overstated.

A version of this article was originally published in The Patent Magazine in October 2020, and a version of this article featured in Fintech Bulletin in September 2020.

We are pleased to announce that Mathys & Squire has maintained its tier 1 ranking for the PATMA: Patent Attorneys category in the latest edition of The Legal 500 – the definitive guide to the legal market.

As well as top tier recognition for our patent practice, our trade mark team has once again been recommended in the PATMA: Trade Mark Attorneys category. Patent partners Jane Clark, Paul Cozens, Chris Hamer, Alan MacDougall and Martin MacLean, alongside trade mark partners Margaret Arnott and Gary Johnston, have been ranked as Recommended Lawyers in this year’s guide, with Anna Gregson, Philippa Griffin and Craig Titmus recognised as Key Lawyers:

‘Jane Clark is a pre-eminent prosecutor who is always my first choice. [She makes herself] available for all important matters as well as many less important matters.’

‘Paul Cozens produces work of a consistently high quality and is very commercial. He is especially adept at dealing with software in the context of engineering.’

‘The individuals we work with in Mathys & Squire are all highly skilled, clear, driven and provide excellent service, especially under pressure. We would like to single out Chris Hamer, who has been exemplary. Chris is equally at home working with us on patent filings and advice one minute and the next advising CEOs and board members on the status of IP and influencing our commercial strategy. He is always available no matter what time of day.’

‘Anna Gregson and Martin MacLean are accessible, knowledgeable and provide a really outstanding, can-do attitude.’

‘Margaret Arnott has played a hands-on role in managing all of our trade mark work, and promptly makes herself available to discuss matters and management issues. She has quickly adapted the way her team works to meet our operational requirements and manage costs.’

‘Margaret Arnott explains everything in plain English, which makes decision-making much more straightforward.’

‘The team under Margaret Arnott’s lead are well organised, reliable and responsive. We value their timely reminders and also that they are always keen to provide advice and support.’

‘Craig Titmus is an exceptional lawyer. He has read our patent so carefully and thoughtfully that his work with the patent offices tends to result in our favour. He presents the commentary and issues with such clarity that we don’t need a legal interpreter to understand and respond to them. This saves a lot of time and fees. Besides being a really clever lawyer, Craig is a truly nice person. We hope to work with him for all of our IP and patents going forward.’

Praise for Mathys & Squire’s patent practice includes:

‘The team has an excellent technical understanding of our technology area, which is very niche and hard for most individuals to grasp. This makes the patent development process so much easier. During the process of trying to get the invention down on paper, the team are able to suggest areas of potential innovation or to point out common knowledge at a very early stage, saving time and money but at the same time potentially generating new commercial IP in the form of sub patents.’

‘Broad experience across the range of technologies that my company has exposure to.’

‘Extremely responsive and eager to understand my company’s needs. Flexible and accommodating when it comes to matching expectations regarding timing and budget.’

‘The Mathys & Squire team has made the entire process of the patent application an exceptional experience. We have received appropriate advice to enable us to gain better positioning. Their billing is also transparent and has shown good value for money compared to other firms we work with.’

‘Showed great technological knowledge and effective support in prosecution in front of the EPO. Cost effective and very responsive.’

‘The diversity of patent concepts we bring forward in our field across a range of activities is always met by a team of experts with relevant expertise to draft patents quickly, enhance our concepts and provide assurance to our sponsors on the novelty and enforceability of our IP. We have always had priority for important filings. Advice to support our commercial partnerships and their strategic direction has always been generous and valuable.’

‘Mathys & Squire LLP really can’t do enough for you. If you want a firm that will go the extra mile and provide industry-leading client service then I would wholeheartedly recommend them. We have entrusted our most important patent portfolio to them and continue to be impressed by the diligent, professional and successful way they have managed the prosecution.’

‘Approachable and friendly, which is a key factor. Very knowledgeable in all manners of managing, and applying for, IP. Very swift in their response time.’

Our trade mark practice received the following feedback:

‘A partner-led service which has made a strong effort to meet our requirements and adapt to changes within the business.’

‘Very much like working with people who are members of the same team as you.’

‘The team provide us with in-depth knowledge and expertise in relation to all trade mark matters and provide pragmatic advice whether we are registering new trade marks or taking steps to protect existing ones.’

For full details of our rankings in The Legal 500 2021 guide, please click here.

We would like to thank all our clients and contacts who took part in the research, and congratulate our individual attorneys who have been ranked in this year’s guide.

One-stop platform offers small business community access to insightful information and connections to help facilitate the startup process.

We are delighted to announce the launch of our Scaleup Quarter, a one-stop microsite resource focused on smaller and growing businesses, including startups, scaleups and SMEs, to harness their passion and energy for innovation and provide crucial IP services that are dynamic and energetic, adding value and supporting businesses as they grow.

While IP is an important (although often overlooked) aspect of a business’ success in its growth journey, we have partnered with other agencies, accelerators and incubators, including GrantTree, Royal Academy of Engineering Enterprise Hub, Startupbootcamp ASPIRE, and Connected Places Catapult, to offer a full spectrum of early-stage business services. The Scaleup Quarter will provide integrated services and support for growing businesses and entrepreneurs, offering access to bespoke IP advice at each stage of growth as well as building a community where these businesses, individuals, investors, supporters and advisers can come together and learn from those who have already built and scaled up their businesses.

As virtually everything a business creates sets it apart from its competitors and is likely to attract some form of IP, including patents, trade marks, design rights, copyright, trade secrets and IP agreements, it is important to recognise the significance of IP to any business and the importance of protecting it. Mathys & Squire’s Scaleup Quarter provides comprehensive access to a range of tools, resources and content in a single location.

Commenting on the launch, partner Andrew White said: “Startup and scaleup businesses often overlook the vital competitive advantage to be gained by identifying, strategising, protecting and even commercialising IP at the right time in a company’s development. Our Scaleup Quarter offers dynamic businesses at the frontline of innovation an opportunity to utilise our resources, created by an expert team of industry and sector specialists, and join a community of like-minded entrepreneurs.”

To find out more about the Scaleup Quarter and how we can help support your growing business, visit our microsite. To keep up to date with our most recent posts, follow our LinkedIn page: Mathys & Squire Scaleup Quarter.

This article has been featured in Startups Magazine and The Patent Lawyer Magazine.