Mathys & Squire partners Anna Gregson, Dani Kramer and Martin MacLean have been featured in the inaugural IAM Strategy 300 Global Leaders guide.

The guide shines a light on specialists from the major IP markets across North America, Europe and Asia, with a wide range of expertise in IP-intensive sectors such as high-tech and life sciences. Consisting of interviews with these leading strategists, the guide provides insight into how their careers have developed, their thoughts on key trends in the market and their top tips for other IP practitioners looking to progress.

The full Global Leaders interviews are available here: the ‘commercially savvy’ and ‘ultimate safe pair of hands’ Anna Gregson; ‘highly intelligent, vastly knowledgeable and committed to excellence’ Dani Kramer; and ‘one of the top guns of the UK life sciences patent scene’ Martin MacLean.

There is a range of IP options available to manufacturers looking to protect their treasured recipes, whether through copyright, a trade secret or a patent, but how do you know if your tasty treat is eligible and, if so, which IP right you can secure? In this article, published in Baking Europe in December 2020, managing associate Laura Clews provides a brief overview of the options available, along with benefits and pitfalls of each for you to chew over…

The festive period is now upon us, so thoughts turn to spending time with our families, decorating the tree and, of course, food. At this time of year, food and drink manufacturers provide unique twists on classic treats and decadent desserts designed to tickle every taste bud. It is common to spend more on food and drink during the holidays and perhaps even treat ourselves to some luxury priced goods. Statistics by GoCompare Money predicted that, collectively, British households would spend £4.7 billion on food and drink products over the Christmas period in 2018. Accordingly, for manufacturers that manage to produce the ‘must have’ items of the year, Christmas can be a very profitable time. But how do you prevent other manufacturers copying your culinary creations and reducing your market share? Essentially, is it possible to protect a recipe?

Can I copyright a recipe?

Copyright is an exclusive legal right that arises automatically on the creation of an original work and can be used to prevent others from using or commercially exploiting this work without permission. Copyright protects, amongst other things, literary creations, artistic works, original non-literary written work and the layout of published editions of written works, but does this IP right extend to recipes?

Unfortunately, under UK law, copyright protection does not encompass a collection of ingredients or a list of instructions (such as the method steps contained in a recipe which are considered merely functional). Therefore, following a recipe to produce a particular food or drink product would not infringe any copyright of the original author.

Some copyright protection may be provided in the particular literary expression used to describe the method steps of your recipe, however, this protection would not prevent others from publishing your recipe as long as it has been expressed in a different way.

General concepts or ideas cannot be protected under copyright either, and so producers of next year’s cronut would not be able to prevent other companies constructing and/or publishing recipes to make the same or a similar treat (unless other forms of IP protection are in place).

Copyright protection afforded to an author is dependent on national law and so can vary depending on the country in which the original work is considered, however many countries around the world are Contracting Parties to the Berne Convention. The Berne Convention defines minimum standards of protection under copyright (i.e. the same protection must be given to works originating in other Contracting States as would be provided for works originating in that state) and the minimum duration of protection (generally 50 years after the death of the author with the exception of applied art, cinematographic and photographic works) under copyright law.

Is it best to keep recipes as a trade secret?

Trade secrets encompass any information that is commercially valuable to a company, including secret recipes. In accordance with The Trade Secrets (Enforcement, etc.) Regulations 2018, to ensure that your recipe is covered as a trade secret you simply need to demonstrate that:

(a) it is secret in the sense that it is not generally known among, or readily accessible to, people who normally deal with that kind of information

(b) it has commercial value because it is secret, and

(c) reasonable steps have been taken in order to keep the information secret.

The requirement of ‘reasonable steps’ can include password protecting documents containing essential information and marking them as ‘confidential’, ensuring trade secrets are protected in employment contracts, using confidentiality agreements – such as non-disclosure agreements – when discussing confidential information with anyone outside your company, limiting the number of people with access to the information, and training staff members on how confidential information should be handled.

While there is no uniform legal framework globally for a ‘trade secret’, in general, unfair practices with regards to confidential information, such as breach of contract or breach of confidence, are considered actionable. Similarly, the remedies available for unlawful acquisition and use of trade secrets can vary based on the legal system in place. For example, trade secrets in the US are governed by The Economic Espionage Act (EEA), under which the theft of a trade secret can result in imprisonment and fines.

What are the benefits of trade secrets?

The basic requirements to ensure that your recipe is classed as a trade secret are simple to implement, cost-efficient and provide effective protection in some cases. Furthermore, the protection provided by a trade secret will remain in force for as long as that information remains secret.

In addition, ownership of a trade secret can be used as an effective marketing strategy, creating hype and mystery around your product. Some of the best-known examples of trade secrets in the food and drink industry include recipes for Coca Cola and the KFC coating (containing a blend of 11 herbs and spices). Both companies publicise the extreme methods employed to ensure that these recipes do not fall into the wrong hands, emphasising just how special and unique their products are. For example, Coca Cola states that the only notation of its recipe is stored in a purpose built vault at the company headquarters in Atlanta and only two senior executives know the secret formula at any one time (these staff members are, of course, forbidden to travel on the same plane). Similarly, KFC has publicised that its secret recipe is secured in a vault in Louisville, which has been reinforced with two feet of concrete to ensure that competitors cannot tunnel or drill into the vault.

In the event that a third party unlawfully obtains or uses information classed as a trade secret, possible remedies available to the owner under UK law include: obtaining a court order (i.e. an injunction) to prevent the use or disclosure of the trade secret, recall or destruction of any infringing goods from the market and monetary relief in the form of damages.

What are the potential issues with trade secrets?

Trade secrets can be useful where it is difficult (if not impossible) to derive the ingredients or process used to produce the food or drink product. However, they do not provide protection if another company legitimately produces the same product or manufacturing process. They also do not provide protection if a third party is able simply to reverse-engineer the product.

Further challenges may arise as a result of the UK’s Food Labelling Regulations, which require food and drink products with two or more ingredients (including additives) to provide a list of the ingredients in order of weight (with a few exceptions). Accordingly, if your secret recipe relies on the inclusion of a specific ingredient, you may be required to publicly disclose this information.

For some companies, patents may provide a more reliable form of protection particularly where a consumable product could be reverse-engineered, if the essential ingredients must be disclosed because of UK Regulations, or if there are other competitors/potential competitors working towards the same target product.

What protection do patents provide for recipes?

A patent is an IP right granted by a specific country’s government for a limited time period, typically 20 years from the date of filing. Where a patent is directed to a product, it allows the owner to stop others from making, using, offering for sale, selling, or importing that product within the territory for which the patent has been granted. For a specific process, the owner can prevent others from using that process within the relevant territory without the patent owner’s consent.

What can be protected?

A variety of food and drink inventions are suitable for patent protection – for example where the product has an improved taste, texture or appearance whilst reducing fat or sugar content; a combination of ingredients which produce a synergistic effect; a non-obvious substitution for a commonly used ingredient (for example, E numbers); and methods of altering the flavour profile of products.

Faster or more cost-effective manufacturing methods; methods of producing new products or method steps which provide an unexpected result can also be suitable for patent protection.

In the same way that trade secrets can be used to publicise particular food and drink products, owning a patent can also increase public awareness and interest. In one example, as highlighted in numerous articles/blog posts, Nestlé developed a method of producing porous particles containing sugar which could be used to reduce the sugar content of confectionery without detrimentally affecting the sweet taste expected by consumers (see WO 2017/093309).

What criteria do I need to meet?

In order to obtain a granted patent, most territories require the inventor to at least demonstrate that the invention is novel, involves an inventive step and is capable of industrial application.

Novelty

The claimed invention must not be publicly disclosed before the date on which the application is filed -e.g. publicising your invention on the company website/blog/social media, selling the product, or displaying it a tradeshow (where someone might determine the novel features from the product itself) could invalidate any later filed patent application.

For this reason, it is essential that manufacturers avoid discussing the invention with anyone outside their company (e.g. investors or suppliers) before the date on which the patent is filed, or, if this cannot be avoided, ensure that confidentially agreements are in place beforehand.

Inventive step

The claimed invention must also provide a non-obvious solution to a technical problem in view of what was known before the filing date of the patent application. Essentially, the invention must be shown to go beyond standard development within that field. The assessment of inventive step can vary depending on the particular jurisdiction in question and so it is often beneficial to seek professional advice from a local attorney when determining whether your invention would likely be considered to meet this requirement.

Industrial application

It is necessary also to show that the claimed invention is capable of exploitation within an industry. Most products and processes within the food and drink industry inherently meet this requirement.

What are the potential issues?

Patenting inventions can be a costly process, especially as the number of territories in which you require protection increases, so it is beneficial, particularly for start-up companies, to carry out a critical assessment of where their product or process will be sold. Alternatively, if their company does not intend to exploit the invention, it is important to determine where they are most likely to license the product/process.

As patent protection typically only lasts for 20 years from the date on which the application is filed, it is worth noting that upon expiration, the recipe, product or process can be freely used by other companies.

Whilst there are different options available for protecting the delectable creations developed by food and drink manufacturers, the type of protection best suited to these products can depend on the product itself and, of course, the commercial strategy of the business.

Mathys & Squire is delighted to have been recognised in JUVE Patent’s UK rankings 2021. Now in its second year, the guide brings together UK patent practices, solicitors and barristers with leading reputations in the UK patent law market.

Despite the challenging events that took place in 2020 (the global coronavirus pandemic, Brexit and the UK’s withdrawal from the UPC agreement to name just a few), JUVE Patent’s research has shown that ‘the UK’s patent lawyers have held on tight’ and that the ‘market remains more or less stable’, in the face of adversity.

For the second year, Mathys & Squire has been featured as a recommended firm in the category of Patent Filing – specifically in the fields of pharma and biotechnology; medical technology; chemistry; digital communication and computer technology; electronics; and mechanics, process and mechanical engineering.

Partner Chris Hamer has received a specialist Leading Individual ranking in this year’s guide, one of only 10 UK patent attorneys noted for their technical speciality – see here.

Chris Hamer and Jane Clark have retained their Recommended Individual status for a second year for their expertise in ‘Chemistry’ and ‘Digital communication & computer technology/mechanics, process and mechanical engineering’ respectively, while Hazel Ford and Philippa Griffin have been newly awarded rankings in the 2021 guide as Recommended Individuals in the fields of ‘Pharma and biotechnology’.

To see the JUVE Patent UK rankings for 2021 in full, please click here.

Just two months after the UK Supreme Court’s decision (as reported here) which held that a UK court has the jurisdiction to set global SEP rates, the Shenzhen Intermediate Court made the first decision ever (Guangdong Oppo Mobile Telecommunications Corporation, Ltd v Sharp Corporation) to confirm a Chinese court’s jurisdiction to determine global FRAND rates for SEPs.

Background

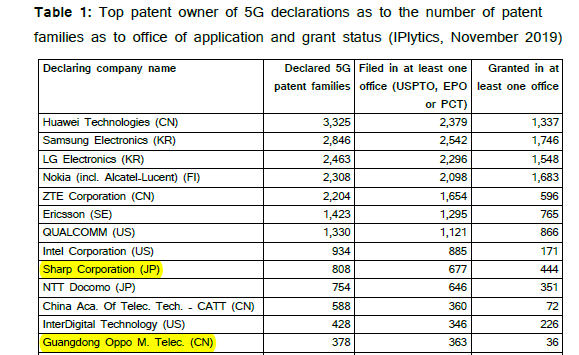

Guangdong Oppo Mobile Telecommunications Corp., Ltd (Oppo) is a Chinese company specialising in electronic and mobile communication products such as smartphones, audio devices and power banks. Sharp Corporation (Sharp) is a Japanese corporation that designs and manufactures electronic products. In the latest 5G patent report released by IPLytics, both Sharp and OPPO ranked as top patent owners of 5G patents (as one indicator of leadership in the telecoms industry) and Oppo was described as a company ‘newly entered into the market’.

Back in October 2018, Sharp sent Oppo a list that included a large number of SEP patents that Sharp was willing to license to Oppo. Oppo and Sharp then started licensing negotiations in February 2019. During the negotiations, Sharp filed patent infringement lawsuits against Oppo in both Japan and Germany for infringing its 4G/LTE patents.

The case

In March 2020, Oppo filed the first instance case against Sharp at the Shenzhen Intermediate Court for:

- Sharp’s breach of FRAND terms during the licensing negotiation, including ‘coercing Oppo into negotiation using infringement injunctions, overpricing and unreasonably delaying the negotiation’;

- global SEP rates of Sharp’s 3G, 4G and Wi-Fi SEP portfolio; and

- a compensation of 3 million RMB (350,000 GBP) for the breach of FRAND terms from Sharp.

The decision

Sharp raised an objection to the Shenzhen Intermediate Court’s jurisdiction over this SEP licensing dispute, arguing that the case should be dealt by a Japan Court, and that the global SEP rates for Sharp’s 3G, 4G and Wi-Fi SEP portfolio is beyond the jurisdiction of the Shenzhen Intermediate Court. The Shenzhen Intermediate Court made a decision in respect of Sharp’s jurisdiction objection in October 2020, as follows:

Whether a Chinese court has jurisdiction over the case

In light of the fact that an SEP licensing dispute is neither a typical contract dispute nor a typical infringement dispute, the Shenzhen Intermediate Court considered a few factors to determine the jurisdiction, such as whether the implementation of the patent or the performance of the contract, is within the territory of China – i.e. whether the SEP licensing dispute is properly connected with China. If one of such actions is within the territory of China, the case shall be deemed to have a proper connection with China and the Chinese court shall have jurisdiction over the case.

In the present case, the plaintiff Oppo is a Chinese company and its production, research and development take place in China. The defendant Sharp is the patentee of the Chinese patents and has property interests in China. Therefore, the court held that the case is properly connected with China and the Chinese court thus has jurisdiction over the case.

Whether the Chinese SEP rates should be separated from the global SEP rates

The court first pointed out that evidently, the previous licensing negotiation between the two parties concerned the global SEP rates of Sharp’s 3G, 4G and Wi-Fi SEP portfolio.

Secondly, the court held that global SEP rates will improve the overall efficiency by solving the dispute between the two parties fundamentally and avoiding multiple litigations in different countries – and therefore such global SEP rates are in line with the intent of FRAND terms and should not be separated from the Chinese SEP rates.

Conclusion

This might be one of the first cases worldwide that involves setting global rates for Wi-Fi SEPs. The consideration of global SEP rates has thus expanded from cellular networks such as 3G and 4G to WLAN.

Perhaps more importantly, this decision holds that a Chinese court is competent to hear issues relating to the setting of global FRAND rates for SEP patents, much like the UK Supreme Court recently held that it was competent to decide on the setting of global FRAND rates for SEP patents. However, this first instance decision was ruled by an intermediate court in China. Therefore, the decision may be appealed, and it will be interesting to see whether this decision will be upheld by the Chinese Supreme People’s Court.

The EPO’s Technical Board of Appeal 3.3.01 in recent decision T421/14 (and related decision T799/16) has provided guidance on when the requirements of sufficiency are met for claims directed to a second (or further) medical use of a known product – in particular where the therapeutic effect is only achieved in a subpopulation of responders and not the patient population as a whole. The decision confirmed that the existence of a group of non-responders does not result in a lack of sufficiency for claims directed to a general population and that the group of non-responders does not need to be excluded.

Established EPO case law for second medical use claims states that the attainment of the claimed therapeutic effect is a functional technical feature of such claims. To meet the requirements of sufficiency, the therapeutic efficacy of the composition and dosage regimen for the claimed indication must be credible. EPO case law has also established that the presence of a non-working embodiment is acceptable, as long as the specification contains information on the criteria needed to identify the working embodiments. Against this background, decision T421/14 considers the issue of sufficiency in a situation where the claim is directed to a general population of patients but encompasses a large group of non-responders.

The claims in question related to a dosage regime comprising aminopyridine for increasing walking speed in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients. MS, like many other diseases, shows a wide variability in pathology which results in only a proportion of patients responding to treatments. The application as filed acknowledged that it was known that only a proportion of patients, estimated to be about one third, responded to treatment with aminopyridine.

The opponent argued that the data within the patent did not demonstrate a therapeutic effect across the full scope of the claims due to the large proportion of the patient population treated being ‘non-responders’. Since the claims did not specify a step of initially identifying a patient as either a responder or non-responder, the opponent argued that the claim scope was incommensurately broad because it encompassed the treatment of patients not responding to the claimed treatment.

The Board of Appeal did not agree with the opponent’s position and stated that “the existence of non-responders is not a reason to deny sufficiency of disclosure” and that non-responders do not have to be excluded or disclaimed. The Board of Appeal also acknowledged that the existence of non-responders is “a common phenomenon which is observed with drugs in many treatment areas” and that it is common practice to treat patients with a drug and change their medication if they do not respond to treatment.

The Board of Appeal held that the criterion of sufficiency of disclosure is met if it can be shown that a relevant proportion of patients benefits from a treatment and that it has acceptable safety, since in these circumstances the skilled person in the art has the necessary technical information to perform the treatment. As the Board notes, the existence of non-responders is a common phenomenon, and innovators will therefore be reassured that in general this does not preclude a second medical use patent from being obtained. Questions remain regarding the requirement that a ‘relevant proportion’ of patients must benefit from the treatment, but it is interesting to note that the Board found that this requirement was met even when only a minority of patients were responders.

Today, 25 November 2020, the EU Commission published a new intellectual property action plan. The action plan, touted as “an intellectual property action plan to support the EU’s recovery and resilience” outlines possible future moves, noting that intangible assets are “the cornerstone of today’s economy”, with IPR-intensive industries generating 29.2% (63 million) of all jobs in the EU during the period 2014-2016, and contributing 45% of the total economic activity (GDP) in the EU worth €6 trillion.

The action plan also notes that the quality of patents granted in Europe is among the highest in the world, and that European innovators are frontrunners in green technologies, and leaders in specific digital technologies, such as connectivity technologies. That being said, the action plan notes that while smart intellectual property (IP) strategies can act as a catalyst for growth, European innovators and creators often fail to grasp the benefits of IP.

The action plan indicates that the Commission is willing to take stronger measures to protect European IP, to increase IP protection amongst European SMEs and to help European companies capitalise on their inventions and creations.

Ambitiously, the action plan also notes that the EU aspires “to be a norm-setter, not a norm-taker” and is keen to seek ambitious IP chapters with high standards of protection in the context of Free Trade Agreements, to help promote a global level playing field.

We summarise some of the key takeaways here.

Unified Patent (UP)

The implementation of the Unified Patent is seen as a priority in the action plan, indicating that it will reduce fragmentation and complexity, and will reduce costs for participants, as well as bridging “the gap between the cost of patent protection in Europe when compared with the US, Japan and other countries”. The action plan also indicates that it will “foster investment in R&D and facilitate the transfer of knowledge across the Single Market”.

SEP licensing

With the introduction of 5G and beyond, the number of standard essential patents (SEPs), as well as the number of SEP holders and implementers, is increasing (for instance, there are over 95,000 unique patents and patent applications supporting 5G). The action plan notes that many of the new players are not familiar with SEP licensing, but will need to enter into SEP arrangements, and that this is particularly challenging for smaller businesses.

One area that has garnered a lot of press attention recently relating to the licensing of SEPs, and in particular to businesses that are perhaps not as familiar with SEP licensing, is that of the automotive sector. The action plan acknowledges this and notes that “although currently the biggest disputes seem to occur in the automotive sector, they may extend further as SEP licensing is relevant also in the health, energy, smart manufacturing, digital and electronics ecosystems.”

To this end, the Commission is considering reforms to further “clarify and improve” the framework governing the declaration, licensing and enforcement of SEPs. This includes potentially creating an independent system of third-party essentiality checks, and follows off the back of a pilot study for essentiality assessments of Standards Essential Patents and a landscape study of potentially essential patents disclosed to ETSI also published alongside the action plan.

Modernising EU design protection

The Commission has indicated that it wants to “modernise” EU design protection “to better reflect the important role design-intensive industries play in the EU economy”. At present, the Commission is asking for stakeholder feedback on the options for future reform. Recent results of an EU evaluation show that the current legislation works well overall and is still broadly fit for purpose. However, the evaluation has also revealed a number of shortcomings, including the fact that design protection is not yet fully “adapted to the digital age” and lacks clarity and robustness in terms of eligible subject matter, scope of rights conferred and their limitations. The Commission also considers that it further involves partly outdated or overly complicated procedures, inappropriate fee levels and fee structure, lack of coherence of the procedural rules at Union and national level, and an incomplete single market for spare parts.

Updating the SPC system

While the Commission notes that, following an evaluation, the Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) framework finds that the EU SPC Regulations “appear to effectively support research on new active ingredient, and thus remain largely fit for purpose”, it believes the EU SPC regime could be strengthened to reduce red tape, improve legal certainty and reduce costs for business. One option being touted is to introduce a centralised (‘unified’) grant procedure, under which a single application would be subjected to a single examination that, if positive, would result in the granting of national SPCs for each of the Member States designated in the application. The creation of a unitary SPC, complementing the future unitary patent, is listed as another option.

Patent pooling in times of crisis

The EU Commission notes how the pandemic has highlighted the importance of effective IP rules and tools to boost innovation and secure fast deployment of critical innovations and technologies, both in Europe and across the globe, but that it sees a need to improve the tools in place to cope with crisis situations. To this end, the action plan includes proposals to introduce possible mechanisms for rapid voluntary IP pooling and better coordination if compulsory licensing is to be used.

Increasing access for SMEs to IP protection and the introduction of an “IP voucher”

The action plan notes that only 9% of EU SMEs have registered IP rights. It aims to help SMEs better manage their IP and improve their competitiveness by giving EU SMEs easier access to information and advice on IP. Through the EU’s public funding programmes and further rolled-out at a national level, EU SMEs will get financial aid to finance so-called IP scans (comprehensive, initial, strategic and professional advice on the added value of IP for the individual SME’s business), as well as certain costs related to IP filings.

This will happen through the implementation of an “IP voucher”, which is made available in co-operation with the EUIPO, providing co-funding of up to €1,500 for:

- IP Scans: up to 75% of the cost and/or

- registration of trade marks and design rights in the EU and its Member States: up to 50% of the application fees.

SMEs will be able to apply as of mid-January for the IP voucher, through a dedicated website. We understand that the voucher will be provided on a “first come first served” basis.

The action plan also indicates the EU Commission’s intention to make it easier for SMEs to leverage their IP when trying to get access to finance, and that this may be done for example through the use of IP valuations.

EU toolbox against counterfeiting

The EU commission notes that counterfeiting is still a major problem for European businesses and proposes that an “EU toolbox” is set up to set out a co-ordinated European approach on counterfeiting. The goal of this EU toolbox should be to specify principles for how rights holders, intermediaries and law enforcement authorities should act, co-operate and share data.

AI and blockchain technologies

The action plan notes that in the current digital revolution, there needs to be a reflection on how and what is to be protected – perhaps a nod to the recent litigation we have seen regarding whether an AI can be considered as an inventor. The action plan in particular notes that questions need to be answered as to whether, and what protection should be given to, products created with the help of AI technologies. A distinction is made between inventions and creations generated with the help of AI and the ones solely created by AI. The action plan notes that the EU Commission’s view is that AI systems should not be treated as authors or inventors, which is the approach taken by the EPO, but that harmonisation gaps and room for improvement remain and the EU Commission has indicated that it intends to engage in stakeholder discussions in this respect.

Conclusion

There is much to take in from the action plan, and we will closely monitor developments in all of the above areas to see what will be implemented and when.

This article was published in Global Banking & Finance Review in December 2020.

We are pleased to announce the appointment of Robin Richardson as associate to our trade mark practice, bringing the team headcount to a record high of 13 (made up of attorneys and paralegals), across our London, Birmingham and Manchester offices.

Robin is an attorney of the High Court of South Africa, a qualified trade mark attorney and soon to be UK qualified solicitor. He has several years of experience in trade mark, domain name and copyright protection, working with clients ranging from large multinationals through to newly formed startup companies. Robin has filed and prosecuted trade mark applications in the UK, EU, Africa and worldwide. He is an accredited domain name adjudicator with the South African Institute of Intellectual Property Law and settled a number of disputes before moving to the UK in 2018.

Robin obtained a B.SocSci and L.LB (Law) from the University of Cape Town and a Masters of Law, specialising in Intellectual Property Law from Queen’s University in Canada. Robin is a Fellow of the South African Institute of Intellectual Property Law and a South African-qualified trade mark practitioner.

After beginning his career with KISCH IP in South Africa where he worked for several years, Robin then joined Womble Bond Dickinson (UK) LLP, based in their Leeds office, in 2018.

Commenting on his appointment, partner and co-head of the Mathys & Squire trade mark team, Gary Johnston, said: “We are delighted to welcome Robin to the firm as our trade mark practice grows. His extensive trade mark skills and international experience will further augment the capabilities of our trade mark practice. Robin has a strong passion for solving domain name, trade mark, copyright and internet based legal issues which will add to our offering to clients. He will be a great asset to the firm.”

Robin Richardson added: “I am thrilled to have the opportunity to be working with the highly regarded team at Mathys & Squire. I share with them the same values and level of client service. I look forward to working with the firm, its innovative clients and contributing to the firm’s continued growth and development.”

This release has been published in World Trademark Review and Intellectual Property Magazine.

The EPO Board of Appeal has now issued its written decision in T 844/18 confirming the revocation of EP-B-2771468, an important CRISPR patent belonging to the Broad Institute, MIT and Harvard. The case was being widely followed due to the priority entitlement issues it raised. James Wilding and Alex Elder of Mathys & Squire represented one of the opponents.

The hearing was covered in our earlier news item here. To recap, the case turned on the issue of ‘same applicant’ priority. The PCT request for the application from which the patent derived had not included all of the applicants for the US provisional applications from which priority was claimed or their successors in title. The proprietors argued that this did not matter, because:

- the EPO does not have the power to assess legal entitlement to priority,

- in the case of joint applicants for a priority application, each can exercise the right of priority without the others, and

- the omitted PCT applicant was not, under US law, an applicant for the relevant invention in the US provisional applications or a successor in title thereto, because they had not contributed to that invention or derived rights from a contributing inventor.

At the hearing, the Board rejected all three arguments, consistent with established EPO case law and practice. With the written decision, we know the Board’s reasons:

In relation to the first argument, the Board concluded that the EPO’s power to assess ‘same applicant’ priority derives from the European Patent Convention (EPC): “Article 87(1) EPC clearly sets out a requirement that the EPO examines the ‘who’ issue of priority entitlement”. The Board rejected the proprietors’ analogy between the determination of entitlement disputes, which the EPO is not empowered to do, and the assessment of ‘same applicant’ priority, which the Board confirmed to be a formal assessment and not substantive.

In relation to the second argument, the Board firmly endorsed the current approach of the EPO, according to which all of the applicants named on a priority application, or their successors in title, must be named on the later European filing in order to introduce priority rights. Article 4A(1) of the Paris Convention and Article 87(1) EPC provide that ‘any person’ who has duly filed an application for a patent enjoys the right of priority, or their successor in title. The Board accepted that the ordinary meaning of ‘any person’ was ambiguous, but found support for the ‘all applicants’ interpretation in the authentic French text of the Paris Convention, in the object and purpose of the Paris Convention, and in the “many decades of EPO and national practice”. The Board further concluded that the bar to overturning the long-established case law and practice “should be very high because of the disruptive effects a change may have.” Those disruptive effects include the potential proliferation of priority-claiming applications and a significant shift in the prior art landscape.

In relation to the third argument, the Board held that it is the Paris Convention that determines who the ‘any person’ is who duly filed a priority application and who therefore holds priority rights. According to the Board, that person is simply “the person or persons who carried out the act of filing”, this requiring a formal assessment without regard to inventorship – consistent with earlier EPO case law. Accordingly, it was the unity of all of the applicants named on the US provisional applications who held priority rights, irrespective of inventive contribution.

In firmly rejecting the proprietors’ three arguments, the Board has maintained the status quo. Perhaps to underscore the point that ‘nothing has changed’, the decision has been coded for non-distribution to other Boards and it will not be published in the Official Journal of the EPO, notwithstanding the attention the case has drawn and the issuance of an EPO press communiqué (published today, 6 November) announcing the written decision. Whether the decision has a significant impact remains to be seen: the question of EPO power to assess legal entitlement to priority is pending in other appeals.

This article was published in The Patent Lawyer Magazine in November 2020.

As covered in our previous article (read the summary here), in September 2020 the LG München I (District Court of Munich I) decided in favour of Nokia in a preliminary injunction against Lenovo, in which the SEP case related to a video standard (H.264 – also known as MPEG-4 part 10), which Lenovo uses in its laptops and PCs.

Shortly after Lenovo appealed the decision against it having to remove the concerned products from its German website, the OLG Munich (Munich Higher Regional Court) made an unexpectedly quick decision on the appeal, and has now stopped the enforcement of the interim injunction. Lenovo’s products can now be ordered again on the company’s homepage.

In the present case (21 O 13026/19), the Court of Appeal has based its decision on the high probability that the patent in dispute lacks legal validity. In the German patent infringement system, the validity of the patent is not examined by the infringement court, but by the Federal Patent Court in a separate procedure (bifurcation). The infringement courts, however, have the possibility to suspend their proceedings if it is highly likely that the patent in dispute lacks legal validity. In the present case, the OLG has thus justified the revocation of the first instance ruling.

The decision of the OLG Munich suspends the preliminary injunction of the LG München, but on the basis of procedural grounds. It remains to be seen whether the Court of Appeal, in its written reasoning, makes further statements in the context of an orbiter dictum, which deals with the application of the FRAND criteria by the court of first instance.

Towards the end of September 2020, the LG München I (District Court of Munich I) decided in favour of Nokia on a preliminary injunction against Lenovo. The subject matter was an SEP case relating to a video standard (H.264 – also known as MPEG-4 part 10), which Lenovo uses in its laptops and PCs. After payment of the security deposit, which was set at €3.25 million by the LG München, Nokia has now enforced the decision and thereby stopped Lenovo from selling the respective products in Germany. The tech company has also had to remove the products concerned from its German website. Lenovo has already announced that it will not accept this decision and has appealed.

This infringement is only a minor issue in the present decision, while the focus is on the application of the FRAND criteria as established by the Court of Justice of the European Union (ECJ) in Huawei v ZTE. The Munich Court found that Lenovo’s efforts to reach a licence agreement were not sufficient within the meaning of the FRAND criteria. In the present case, the communication between the parties appears to have taken place in principle without significant delay, but without reaching an agreement on the monetary side of the FRAND conditions.

In doing so, the Munich Regional Court is following the guidance of the Federal Court of Justice in Sisvel v Haier (K ZR 36/17). Perhaps surprising is the low security deposit of approximately €3 million. This may be one reason why Nokia enforced the decision in order to increase the pressure on the licensee Lenovo, which, in the view of the Munich court, is unwilling to accept. The current decision is a further step towards Munich courts being SEP owner friendly. In particular, it further increases the requirements for SEP users and their willingness to negotiate. This positive development for SEP owners certainly leads to increased caution for SEP users in product development, but particularly in ongoing license negotiations. This could also be seen as judges strengthening the patent rights against the plans of the German government to change patent law.