Data provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in an article by The Times, Tech Register, World Intellectual Property Review, Institute of Export and International Trade and City A.M. highlighting a surge in trade mark oppositions following Brexit.

An extended version of the release is available below.

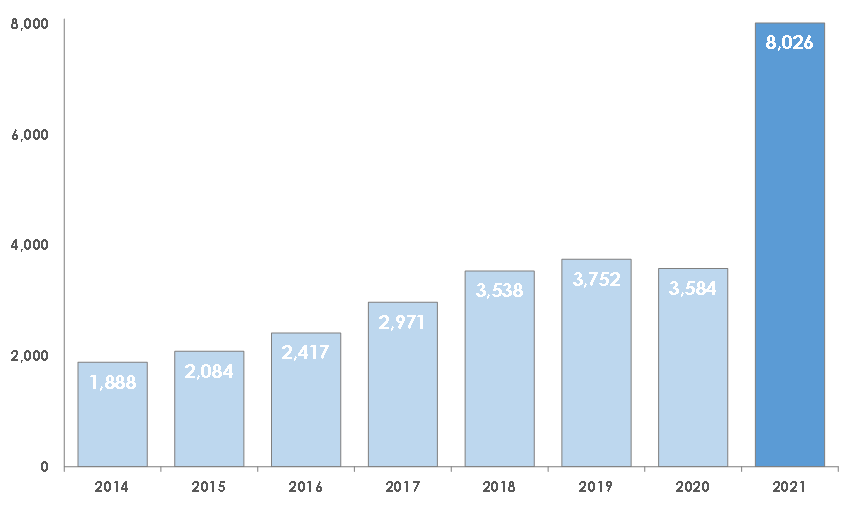

The number of oppositions to UK trade mark applications has more than doubled to a record high of 8,026 in 2021, up from 3,584 in 2020* says leading intellectual property law firm Mathys & Squire.

Mathys & Squire explains that the rise in disputes over UK trade marks has been driven by Brexit. The UK left the EU trade mark system in January 2021, meaning that any business wishing to protect a trade mark in the UK now needs to make a separate application in the UK. This has caused a major rush to file trade mark applications, resulting in a surge in the number of oppositions being filed.

Earlier this year research from Mathys & Squire found there had been a record number of applications for trade marks, with 195,000 applied for in 2020/21, up 54% from 127,000 in 2019/20**.

The Intellectual Property Office (IPO), the government agency that handles trade mark, patent and design registrations, was recently forced to recruit more than 100 new staff to clear a backlog of trade mark applications. This elevated level of trade mark applications – and disputes related to them – is likely to be a long term trend as the UK’s departure from the European Union trade mark system is a permanent one.

Disputes over trade marks, known as trade mark oppositions, occur when a business files a trade mark application with the IPO and another person or business attempts to ‘block’ it. The IPO will determine in opposition proceedings whether a trade mark application should be refused on the basis of an earlier right or other grounds such as bad faith.

Recent disputes over well-known trade marks in the UK have included:

- Amazon opposed an application by a Dubai-based coffee producer covering a range of food and drinks products a similar mark.

- McDonald’s opposed an application to register the trade mark ‘McVegan’ in the UK – it won and was awarded costs.

- Shine TV, the producer of the BBC’s MasterChef TV series, successfully opposed three applications for marks incorporating the words “MASTER CHEF ACADEMY” for education and training services.

Harry Rowe, Managing Associate at Mathys & Squire, comments: “The Brexit-fuelled dash to file trade marks in the UK has inevitably led to more disputes. Businesses need to ensure that they police the register to maintain the distinctiveness and value of their brands.”

“It is likely that this is no short-term spike in disputes – this is what trade mark protection in the UK is now going to look like.”

“Brexit has opened up a whole new battlefield for businesses with valuable brands to protect. Prior to Brexit, trade mark owners could protect their trade mark across all the EU member states in one application. Now that the UK is no longer covered in an EU trade mark, trade mark owners must file two separate applications in order to achieve the same protection.”

“There is now twice as much ground to cover for businesses seeking to protect their investment in their brands.”

Number of trade mark oppositions in the UK surges post-Brexit

* Year end December 31 2021. Source: Intellectual Property Office

** Year end October 31 2021. Source: Intellectual Property Office

UPDATE as of 19 October 2023

The European Patent Office (EPO)’s ‘10-day rule’ will cease to exist from 1 November 2023. From that date, EPO communications will be deemed to be delivered on the same date which they show, rather than 10 days later (as occurs at present). Click here to find out more.

Users of the European patent system will be familiar with the European Patent Office’s (EPO) ’10-day rule’. This is a legal fiction under which official communications from the EPO are normally deemed to have been delivered to the recipient 10 days after the date which they bear. In many cases, it is the end of the 10-day period which is relevant for calculating deadlines, even if the communication was received before then. While not strictly accurate, some users are in the habit of regarding the 10 days as a ‘grace period’ for response to EPO communications.

Although this rule originated as a ‘buffer’ to take into account delays in receiving documents by post, it has continued to be applicable even as the EPO has increasingly moved towards electronic communication. However, this now looks set to change.

At a meeting held by the EPO Committee on patent law on Thursday 12 May 2022, a proposal for ‘dropping’ the 10-day notification rule was preliminarily approved. The proposal still needs to be approved at the Administrative Council meeting in June, but assuming it passes there too, we can expect this change to come into force on 1 February 2023. The proposed change will abolish the 10-day rule regardless of whether communications are delivered electronically or by post.

Essentially, this means that the EPO’s provisions on notification will be brought in line with the PCT, such that the date of a communication will be considered the date of notification and be decisive for determining the expiry of an applicable deadline. As a safeguard against late delivery of communications, the EPO has proposed measures to extend deadlines in cases where delivery of a document is disputed, and it can be established that a document was delivered to the addressee more than seven days after the date it bears. Here the burden will be on the EPO to establish when the document was actually delivered, unlike the PCT, which places the burden on the applicant to prove late receipt.

The proposal to abolish the 10-day rule is part of a wider strategy to support digital transformation in the patent grant procedure. The changes also acknowledge that today’s reality of rapid postal services and electronic communication is very different to the paper-based world that much of the EPC is based on.

Other proposed changes permit transmission of prior art citations to applicants online rather than on paper, acknowledging that such citations might not always be simple written documents but might also be in multimedia formats. The EPO also proposes to rewrite the rules relating to the format of patent application documents in order to relax many of the (now largely obsolete) requirements relating to paper size, quality and formatting, which were designed for documents filed in hard copy. Notably, amendments to the rules on drawings seem to suggest that the EPO might in future allow applicants to submit colour drawings, which would be a very welcome change for applicants in many technical fields. These changes (amongst others in the overall proposal) are proposed to come into force on 1 November 2022, earlier than the proposed notification changes. We will continue to provide updates as more developments at the EPO are made public.

Data provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in an article by The Trademark Lawyer, highlighting a surge in trade marks owned by online fast fashion retailers.

The number of trade marks owned by online fast fashion retailers such as Asos, Boohoo and Shein has increased by 163% from 136 to 358 in the last five years*, shows new research by leading intellectual property law firm Mathys & Squire.

Mathys & Squire says the expansion of the trade mark portfolios reflects the development of fast-moving e-retailers into fully-fledged, multi-brand fashion houses. Key to this strategy is acquiring a formidable portfolio of intellectual property (IP), including both established brands and new trademarks.

Mathys & Squire explains that the size of these e-retailers’ trade mark portfolios is catching up with that of the traditional high street fashion giants. In comparison, the top 10 fashion retailers in the UK by turnover** own a portfolio of 949 trademarks.

Mathys & Squire says expanding their IP portfolios should help fast fashion companies boost their profits, as brand owners typically receive greater profit margins than resellers.

Rebecca Tew, trade mark attorney at Mathys & Squire says: “The growth in the trade mark portfolios of online fashion retailers shows that they are now going toe-to-toe with established high street brands.”

“This expansion of fast fashions brands’ IP portfolios could help boost profit margins in the future.”

Online fast fashion brands such as Asos and Boohoo have begun to rival established high street brands in the size of their IP portfolios. Boohoo now owns 108 UK trade marks, more than Primark (104) and H&M (89), while Asos owns 194 – more than Zara owner Inditex and just shy of Superdry’s 201.Much of this growth comes from acquiring the brands of distressed high street chains such as Karen Millen and Arcadia’s Topshop and Dorothy Perkins.

Mathys & Squire says that there remains value in many legacy brands, including those whose stores have gone into administration.

Rebecca Tew adds: “The way in which online fast fashion retailers have snapped up distressed high street brands highlights that the value of brands can outlast the value of bricks-and-mortar stores. Established brands bring with them name recognition and a loyal following. When combined with the lower overheads of online only retail, the appeal of adding these names to their ‘own brand’ portfolios seems clear.”

“Covid has undoubtedly accelerated the already growing trend towards online shopping, leaving online-only labels in a strong position for future growth.”

*Year ending 31 December, data from Intellectual Property Office

**Largest high street clothing brands by turnover

The 2022 edition of Managing IP’s IP STARS directory has now been released and Mathys & Squire is delighted to have six practitioners named ‘IP Stars’.

We are pleased to congratulate Jane Clark, Paul Cozens and Hazel Ford, who have all been named as ‘Patent stars’, as well as Margaret Arnott, Gary Johnston and Rebecca Tew, who have been ranked ‘Trade mark stars’. Additionally, Philippa Griffin, David Hobson and Andrew White have been featured as ‘Notable practitioners’ in the latest guide.

These IP Stars are senior practitioners who have been recommended or identified as leaders in their firm and/or jurisdiction. Rising star rankings are due to be released in September 2022.

For more information, and to view the rankings in full, visit the IP STARS website here.

Data provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in an article by City A.M. highlighting UK litigation funders’ increased interest in intellectual property cases. Click here to read the article in City A.M.

Eight of the UK’s top 10 litigation funders* are now actively looking to fund intellectual property (IP) cases, says leading intellectual property law firm Mathys & Squire.

Litigation funders pay the legal costs of a litigant’s case in exchange for a share of any damages if the case is won or settled. If the case loses, the litigant owes the funder nothing.

Litigation funding has emerged as a major new asset class for institutional investors over the last decade, meaning there is significant capital to invest in strong intellectual property claims.

IP litigation is a particularly good fit for litigation funding as cases involving the infringement of patents, trade marks and registered designs can be complex, lengthy and international in nature. The cost of pursuing these kinds of claims, often against very deep-pocketed defendants, makes third party funding essential. Of course, the potential for a healthy return, particularly in the US, is another key factor as to why funders find these kind of claims attractive. Even for smaller companies bringing claims, the settlement sums can be significant.

Andreas Wietzke, Partner at Mathys & Squire, says: “Litigation funders see IP cases as a key area to deploy their capital.”

Leading global litigation funder Woodsford says that a particularly attractive growth area for litigation funding is cases of patent infringement by a US corporation against a smaller business such as a UK startup. It is disappointingly common for major tech businesses to meet with startups to discuss their IP under an NDA and then copy their idea, in breach of the NDA.

IP infringement cases in the US can result in very substantial damages being awarded. In 2020, Apple was ordered to pay the California Institute of Technology $838m in a case brought over Wi-Fi technology. In 2016, Inedix Pharmaceuticals won $2.54bn from Gilead Sciences in a dispute over hepatitis C drugs. The year before that, Smartflash Technologies was awarded $533m in damages from Apple related to software patent infringement.

Mitesh Modha, Director at Woodsford says: “Tech giants often assume a small startup won’t have the resources to pursue a potentially expensive and time-consuming patent infringement case. Litigation funders are increasingly enabling David to fight back against Goliath.”

Mathys & Squire says that the availability of litigation funding for UK businesses to pursue IP claims in the US makes it more economically viable to register IP in the US at an early stage. The possibility of pursuing cases using a litigation funder has also led to more UK businesses examining their catalogues of IP for possible instances of infringement by US tech businesses.

Andreas Wietzke says: “Registering your IP in the US can pay for itself many times over if that IP is compromised by an American company.”

“Given the potential for a huge settlement, many companies may have parts of their IP portfolios that have been infringed in the US that are equivalent to ‘Rembrandts in the attic’.”

Small businesses benefit from the increase in litigation funding for IP disputes as it will allow them to challenge the infringement of their IP by larger businesses without having to risk their own cash.

Larger corporations can also benefit from litigation funding through agreements for funders to actively pursue cases on their behalf. This way large businesses can defend their IP portfolios without having to expend resources on actively monitoring infringements themselves.

Andreas Wietzke adds: “For smaller businesses, using a litigation funder means more capital to invest in growth. For bigger businesses, it can allow them to completely outsource IP defence and take it off the senior management agenda.”

“Litigation funding increases the value of IP in particular for smaller companies. For some of them the cooperation with a litigation funder can even be symbiotic, when the startup is interested in an injunction to secure the market and the funder gets a significant part of the financial benefit.”

If a litigation funder wins a patent case on behalf of a company in one EU country then its sets a non-binding precedent in other EU countries – making it easier for the funder to collect damages across the EU. The upcoming Unified Patent Court (UPC) will boost this by offering an EU wide litigation option providing one ruling to be enforced in all participating countries.

*The Top 10 UK litigation funders by assets

(C) Naomi Korn Associates & Mathys & Squire 2022. Some Rights Reserved. These case studies are licensed for reuse under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike Licence.

The following case study has been taken from the “Implications of COVID-19 on SMEs – Reassessing the Role of IP in Multiple Sectors and Industries” report written by Naomi Korn Associates and Mathys & Squire Consulting, November 2021. This case study reviews the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SMEs (from early 2020 through to the first quarter of 2021). It focuses on the industries most affected by the crisis and whether intellectual property (IP) and IP management may have helped mitigate its impact through adaptation and change.

Sector overview

The logistics sector has been one of the worst affected industries by the COVID-19 pandemic and continues to suffer setbacks due to renewed lockdowns, travel limitations, and an overall decreased demand. This has required changes to be made by companies which are adapting to a significant consumer demand decrease. Some businesses had to adapt their business proposition and market strategy, to aid the move from physical stores to e-commerce platforms. This pandemic has seen a shift from a transport system focused on the movement of large workforces, to providing a service reducing physical contact, yet still capable of transporting food, personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical supplies.

Analysis

Following the spread of the coronavirus in early 2020, the logistics sector has been severely impacted, with notable reduction across ocean, land, and air freight. At the beginning of the pandemic, Chinese ocean freight saw a 10% reduction in cargo transportation journeys, while there was a 20% drop in air freight, largely due to a sharp drop-off in passenger flights, which often also carry cargo. It is notable that air travel has been heavily impacted due to the social distancing requirements in place and trying to reduce the transmission of the virus. An increase in blank sailing due to decreased demand, delays in air travel due to reduced capacity, and a parallel increase in air freight rates, have all contributed to an increased demand for land and rail freight instead. However, localised lockdowns and travel restrictions have also negatively impacted the feasibility of land freight travel [1].

Overall, these reductions have created cash flow problems for many in the logistics industry, with the continued presence of the virus resulting in tens of thousands of people losing their jobs or being placed on furlough, while planned investment in the industry has either been frozen or cancelled. A recent study has shown a 67%-77% drop in public spending on travel in the US, UK, and Germany in the first half of 2020 [2], with large airlines such as Virgin Australia and Flybe declaring bankruptcy in 2020 due to cash flow limitations from flight cancellations and a substantial drop in consumer demand.

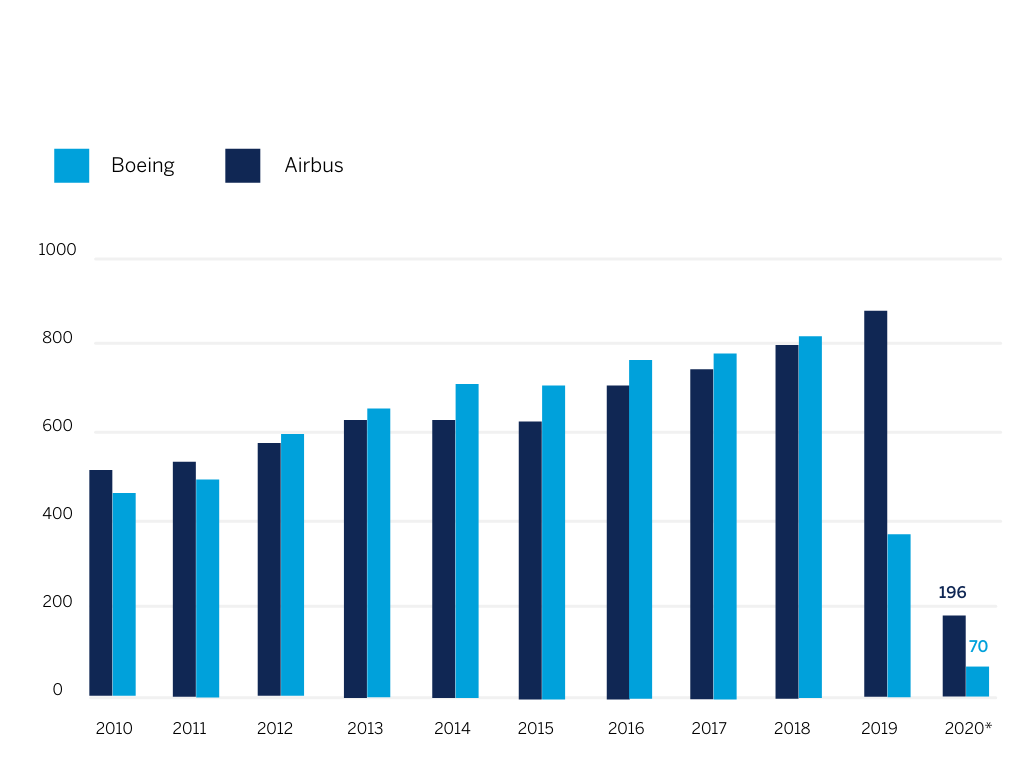

As indicated in Figure 1 below, aerospace manufacturers have also experienced a drastic reduction in demand for new aircrafts. This not only impacts large market players but also the entire supply chain, comprising SMEs from all over the world. The pandemic is expected to cause a contraction in the global air freight forwarding market of between 2%-4% [3]. However, it may also be the case that as normality returns after the pandemic, the aerospace industry starts to reallocate fleets to exclusively serve the air cargo demand, thereby reducing the number of mixed passenger/cargo flights, which are more susceptible to the effects of the pandemic [4].

Crisis critical products [5] such as medical supplies, disinfectant, PPE, and general groceries have seen a significant uptick, although not without challenges in procurement of supply and issues of quality earlier in the pandemic. There has been significant disruption to production value chains, in particular in Asia, as well as trade embargoes and restrictions on movement of certain goods. Consequently, this is likely to increase logistics costs across certain parts of the world for specific goods due to tight regulatory controls and concerns surrounding spreading of the virus.

Business models have also been forced to change, with suppliers increasingly turning to e-commerce platforms, an increased use of electronic cargo visibility and traceability platforms, as well as increased use of automation, robotics, drones and autonomous vehicles [6]. In the longer term, these changes are likely to significantly impact how businesses run and what innovation strategy they develop to further grow. In response to the pandemic and a change in consumer demand, the Chinese company JD developed an Emergency Resources Information Platform (ERIP) for intelligent demand planning, supply risk identification, and visualised tracking for production processes. The ERIP also offers IoT connected automated warehouse management systems and automated guided vehicles to improve efficiency for last-mile logistics, for instance to hospital staff and those under quarantine in Wuhan [7]. Similarly, US based Refraction AI is currently testing last-mile robotics delivery vehicles in Ann Arbor, with vehicles running on the roads, as opposed to footpaths, thereby increasing delivery speeds.

Regarding the response from the logistics industry, there are several lessons that can be learnt about IP management. Companies in the logistics industry have adapted to the digitalisation of the sector by innovating and improving their offering, to match current consumer demands. Thanks to their already existing IP portfolios, as well as new IP assets created through adaptation, companies in the logistics sector have been able to underpin new business and technology models for the protection and exploitation of these assets. Some of the inventions including remote inventory management systems, remote workforce management systems, track and trace systems and digital service delivery. These inventions are protected by copyright, trade secrets and in some cases patents, protecting the IP assets from being infringed on by competitors.

The pandemic has accelerated the digitalisation and generation of robust digital capabilities in the logistics sector and moving forward, these inventions will keep increasing efficiency and reducing costs. As the pandemic begins to come under control, it is the management and protection of these inventions, as well as their importance in contributing to revenues and building value, that management teams must understand.

The Intellectual Property Office of Singapore (IPOS) believes that IP assets and digitalisation go hand in hand and governments and businesses should be seeking to build an ecosystem, focusing on the protection and utilisation of these IP assets, arising from digitalisation. In this context, IPOS has launched an acceleration program designed to expedite the patent granting process to facilitate quicker commercial utilisation of those assets [8]. Recognition of the importance of intangible assets is growing in this sector with a 6.6% increase in transport related patent filings observed by the EPO in 2019, with digital technology and autonomous vehicles patents responsible for much of this growth. In this context, the Chinese logistics firm, JD Logistics has rolled out a fleet of 100 vehicles in Changsu for deliveries home, as well as to hospitals.

However, while the boom in e-commerce has led to significant growth, for many companies it has also led to a marked increase in cases of IP infringement. This raises additional questions surrounding IP responsibility within the logistics supply chain, where traditionally responsibility has been placed on the producer, rather than the retailer or shipper. Moving forward, where patent owners are unable or unwilling to pursue the infringing manufacturer, they may begin to pursue the end retailer or shipper, with significant impacts on the whole supply chain as a likely result. The outcome of current legal cases in the US in this context may potentially spark the revision of supplier agreements from the point of IP protection, as well as opening the supply chain for the analysis of IP risk, thereby having a significant impact on the retail and logistics sectors overall. There is also a need for governments around the world to review their IP enforcement regulations to assist struggling industries, like the logistics industry and support them to enable global economic recovery.

Naomi Korn Associates is one of the UK’s specialists in copyright, data protection and licensing support services.

Mathys & Squire Consulting is an intellectual property consulting team that can support all businesses in capitalising intangible assets.

Naomi Korn Associates and Mathys & Squire Consulting are working in partnership across multiple industries to provide innovative consultancy IP support services.

[1] World Bank Group (2020): The Impact of Covid-19 on Logistics, International Finance Corporation

[2] Statista (2020): Covid-19 Barometer 2020, Statista

[3] Transport Intelligence (2020) Global Freight Forwarding Market Sizing 2020 Covid-19 Impact Analysis, Transport Intelligence

[4] World Bank Group (2020)

[5] Tietze, Vimalnath, Aristodemou, & Molloy (2020): Crisis-Critical Intellectual Property: Findings from the Covid-19 Pandemic, University of Cambridge

[6] World Bank Group (2020)

[7] Capgemini (2020): How digital innovations enabled supply chains to remain operational during the COVID-19 outbreak

[8] IPOS (2021): Acceleration Programmes, https://www.ipos.gov.sg/protect-ip/apply-for-a-patent/accelerated-programmes

We are pleased to announce the appointment of a biotech Partner Iain Armstrong.

Iain has over 20 years’ experience advising clients in the life sciences field, providing practical and pragmatic advice through the entire patent process. He has a particular interest in stem cell technologies, wound healing, and cell therapies (such as CARs), reflecting his background in cell biology. Iain also works extensively on inventions relating to antibody therapeutics, diagnostics, and personalised medicines.

The firm’s new Partner joins Mathys & Squire from IP law firm HGF, where he worked with multiple universities, research organisations and startups across the world. Iain’s practice concentrates primarily on the therapeutic applications of biological inventions, with a particular focus on technologies relating to cell biology.

Martin MacLean, Partner and head of the life sciences team at Mathys & Squire, comments: “I’m absolutely delighted to welcome Iain onboard; it’s a coup for Mathys & Squire to attract a senior attorney of Iain’s calibre. His energy and enthusiasm speak volumes and his track record is exemplary. Iain’s appointment is a major step in furthering Mathys & Squire’s strategic development in the life and medical sciences sectors. His extensive biotech knowledge and legal experience will prove a significant long-term asset to the firm.”

This release has been published in Pro-Manchester, The Patent Lawyer and Juve Patent.

Update: 12 May 2022

T 1444/20 of 28 April 2022 cites and agrees with T 1989/19, finding that “claim-like clauses” in the description, labelled as “specific embodiments of the invention”, did not need to be deleted for the claims to comply with Article 84 EPC. See Reasons, 2.4, which states “the numbered embodiments (…) of the description under the heading “Specific embodiments of the invention” cannot be mistaken for claims, since it is evident that they are part of the description text, and they are not denoted as “claims” either”. Thus, in this instance, the specific embodiments did not result in a lack of clarity of the actual claim, and did not need to be removed.

A recent Board of Appeal decision returns to the topic of description amendments. T 1024/18 is the first decision on the subject since T 1989/18, and indeed the first decision to cite T 1989/19. This new decision appears to backtrack on T 1989/18 – description amendments are likely here to stay.

As a reminder, in T 1989/18, published in December 2021, the Board held there was no legal basis for a requirement to amend the description in line with allowable claims. The decision contradicted earlier decisions, such as T 1808/06, on which the EPO Guidelines wording was primarily based, where it was held that the description must be adapted so that the claims are supported by the description (Article 84 EPC).

The decision also came despite examiners typically insisting on this being completed before agreeing to grant the patent application and despite the revision to the EPO’s Guidelines for Examination in March 2021, which had altered the extent to which examiners should expect the description to be amended (see, e.g., H-V, 2.7 and F-IV, 4.3). As a further reminder, the Guidelines were revised again in March 2022, providing some further clarity on the expected amendments, but not substantially changing the requirements compared to the 2021 guidelines.

The changes to the Guidelines and strict adherence by the examiners increased the care and attention that needed to be taken over amending the description in line with claims, thus increasing workload to attorneys and subsequently, of course, cost to clients. The decision in T 1989/18 therefore appeared to offer some hope that examiners might not adhere to the new Guidelines quite so strictly, and release some of this burden from attorneys and applicants alike.

In T 1024/18, however, EP 2609899 was revoked because an amended description had not been filed with the allowable amended claims on appeal. The Board in this case held that Article 84 EPC required the description to be consistent with the claims throughout, such that the claims are supported by the description as a whole, and it seems the Board of T 1024/18 considered that the previous Board of T 1989/19 placed more emphasis on the clarity element of Article 84 EPC, and insufficient emphasis on support.

It is interesting to note that the two decisions have been treated differently already by the EPO: T 1989/18 was given a ‘D’ distribution (i.e., not distributed to other Boards) and did not appear as a ‘Selected Decision’ on the Boards of Appeal website, whereas 1989/18 was given a ‘C’ distribution (distributed to other Chairpersons)[1] and is a ‘Selected Decision’ on the website. This different treatment may imply the EPO’s feelings towards the topic – that T 1989/18 is merely a slight curveball in proceedings, and that T 1024/18 reinforces decisions that came before it where it was held that the description must be amended in line with the allowable claims.

Indeed, two subsequent decisions also seem to support this. In T 0120/20, the respondent (patent proprietor) argued that following T 1989/18, there was no general provision in the EPC that required an adaptation of the description. However, the Board rejected this line of argument, stating (in 10.2 of the decision), that they did not follow decision T 1989/18, instead agreeing with T 1024/18. In addition, although not explicitly citing either T 1989/18 or T 1024/18, the board in T 2613/18 held that a claim which is inconsistent with the description is not supported by the description under Article 84 EPC (see 2.1.1 of the decision), indicating that Boards of Appeal in general may be more likely to follow T 1024/18 than T 1989/18.

Considering the ongoing conflict and attention to the subject, we expect there will be more decisions that cite T 1989/18 and T 1024/18 and discuss the matter further. We will review these with interest if and when such decisions are issued. It is also possible that the issue could become subject of discussions in the EPO user reviews as part of the Guidelines for Examination revision processes, and that in time a referral to the Enlarged Board of Appeal to settle the matter could be made. Again, if this happens, we will be paying close attention.

The above is not intended to provide legal advice: if you have any questions, please get in touch.

[1] “B” decisions are distributed to Chairpersons and Members; “A” decisions are published in the Official Journal of the EPO.

To celebrate World Intellectual Property Day 2022, Mathys & Squire has collaborated with three SME leaders on a series of articles, exploring innovation and the impact IP has had on each business.

In the final interview of our series, we spoke to Toni Schneider, COO of Ostique, a UK company offering innovative and affordable ostomy care products.

1. How is your idea/invention creating a better future?

There have been incremental developments in ostomy care over the last few decades, yet despite this, products still impact on ostomates’ daily activities and psychological wellbeing. Even the most body-confident ostomates find current products stigmatising and the lack of choice frustrating.

We create innovative and aesthetically empathetic ostomy care products, as we believe that everyone living or adapting to life with a stoma deserves ostomy care that not only delivers on functional needs, but also supports them mentally and physically. We understand that there can be stigmas and challenges that people with stomas will face, and with our product we hope to improve their quality of life for a better future.

2. What were the challenges you or your team faced when growing your business?

Similar to other young businesses, we needed to raise funds to grow our operations and have found the process of fundraising to be challenging. However, we are overcoming this challenge by ensuring we get our brand into the marketplace and connecting with the various networks that support businesses looking to fundraise.

Furthermore, due to the nature of our work, when COVID restriction took place, we were unable to run a few of our daily activities, such as carry out patient focus groups. Despite this, we were very quick to adapt our process and took sessions online, and sent products via post to individual participants.

3. What role does IP play in protecting your invention and supporting your business objectives?

IP is very important to our business, as we invest heavily in developing new and innovative products which address the significant issues of existing ostomy product offerings. We also recognise the vital commercial importance of protecting the company’s innovations to prevent other players in this space from free-riding on our developments. Our IP strategy is thus to seek robust protection for all of Ostique’s IP, where commercially appropriate to do so.

Our earliest patent applications in fact pre-date the incorporation of Ostique as a company (they were filed in the name of our founder Stephanie and were later transferred to Ostique) – emphasising the fact that defensibility has been a core pillar for us from the very start.

4. What advice would you give to your younger self to better navigate your journey?

My advice would be to believe in yourself, self-doubt and imposter syndrome can be your worst enemy and limit your progression. I was fortunate to have a very supportive network of family and friends to encourage myself and Ostique’s CEO, Stephanie.

Also, trust the path you are following, I started a career in law and then founded my own business with my friend. Although I stopped practising law, I use so many of the transferable skills that I learnt to run the business today. Finally, trust your gut!!

5. What forward-looking plans do you have to ensure an even better future for your business and/or the wider society?

We have specific milestones for Ostique to grow and we continue to focus on working with patients impacted by stoma surgery and help integrate them into society, whilst promoting awareness and social inclusion.

6. What activities do you carry out to ensure your business keeps innovating?

We keep an eye on the market as well as ensuring we are signed up to the relevant publications and newsletters to hear the latest industry news. We also consistently collaborate with patients, care-givers, nurses, clinicians and academics to receive feedback to input into our innovative products.

Mathys & Squire recognises the invaluable contribution inventors and innovative businesses offer to building a better future, and we are also aware of some of the challenges they might face. In an effort to help entrepreneurs, startups and scaleup businesses protect their inventions, we launched the Scaleup Quarter, a microsite with resources and a tailored offering for SMEs.

For more information, contact a member of our team.

(C) Naomi Korn Associates & Mathys & Squire 2022. Some Rights Reserved. These case studies are licensed for reuse under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike Licence. The contents should not be considered legal advice. If such legal advice is required, the opinion of a suitably qualified legal professional should be sought.

The following case study has been taken from the “Implications of COVID-19 on SMEs – Reassessing the Role of IP in Multiple Sectors and Industries” report written by Naomi Korn Associates and Mathys & Squire Consulting, November 2021. This case study reviews the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SMEs (from early 2020 through to the first quarter of 2021). It focuses on the industries most affected by the crisis and whether intellectual property (IP) and IP management may have helped mitigate its impact through adaptation and change.

Sector overview

COVID-19 has had an enormous and perhaps irreparable impact on the retail sector worldwide, with social distancing requirements, lockdowns and dwindling sales pushing many businesses to bankruptcy and expediting the shift from physical stores to digital shopping. It is estimated that the pandemic has accelerated the move towards digitalisation by at least five years.

It has also been revealed that department stores experienced a 60% sales decline in 2020, while e-commerce businesses saw sales soar by 20%. The marked decrease in sales from physical stores has pushed large department stores such as Century 21 into administration, while SMEs found themselves struggling to survive in the competitive online environment. A 2019 study estimated that digitalisation is integral to increase global GDP growth[1], which further reinforces the need for businesses to embrace digital technologies to weather the pandemic and ensure rapid recovery[2].

Another consequence of the pandemic is the disruption of traditional supply chains, highlighting the importance of having a more localised supply chain, to support local businesses and increase their brand awareness. In hindsight, this can be a way to counter some of the gradual decline of the high street stores in the UK and many other countries worldwide.

Analysis

Despite the challenges faced by the retail industry, there have been several success stories, most notably e-retail platform such as Ocado, and Amazon, as well as food delivery services such as Uber Eats, Deliveroo and Just Eat. These platforms have grown from strength to strength with large portions of the population now doing most of their shopping online. Although items such as clothing saw a decline in sales overall, other items such as groceries, PPE, alcohol, entertainment, home improvement or construction materials grew by 10%-15%, largely due to people isolating and further lockdown restrictions. Many companies have pivoted to this new normal in two main ways: by offering online shopping with the order being shipped to the customer; or via a “buy online and pick-up in store” / “click and collect” option, where the item is simply collected at the store entrance, with minimum interaction. Amazon experienced a 40% sales growth in 2020 due to the pandemic, whilst US based Walmart saw a 97% increase in its e-commerce sales in Q2 of 2020 alone.

In order to meet these increasing requirements, many of these companies have developed new technical innovations, both in terms of e-commerce platforms and user interfaces, but also modes of processing and delivering such high volumes of online orders. Multi-channel distribution approaches have allowed businesses to provide greater flexibility and less reliance on a single point of the supply chain[3]. It is worth noting however, that the increased exposure for businesses through digitalisation and e-commerce also increases the risk of potential counterfeiting and IP theft. The traditional focus on protection of registered rights and employee know-how may be insufficient, with a pivot towards cyber security becoming increasingly important. It is also progressively vital that as businesses ‘go digital’, by turning to e-commerce platforms or developing their own software solutions. With such solutions, it is important that businesses understand their responsibilities and obligations when using open source code, especially when looking to commercialise their own solution containing open source software.

Ocado, a leading provider of grocery delivery and logistics, is a good example of a business that has created additional value for through its innovations and licensing of IP to third parties. At the same time, Ocado has been able to foster innovation in adjacent areas through its venture program, supporting and acquiring disruptive technologies. This is achieved by expanding the Ocado patent portfolio, which now covers innovations relating to its core competencies surrounding AI and machine learning; robotics; IoT and edge intelligence; simulation; and modelling and forecasting. In this way, Ocado uses its IP as a foundation layer for a wider defensive strategy, while at the same time ensuring awareness of competitor strategies, what impact they have on Ocado and how to react.

In the meantime, home delivery giants such as Amazon have amassed large patent portfolios, including some IP rights that are relevant to the e-retail sector, such as drones, drone noise reduction, order management systems, mobile loading platforms, and autonomous vehicles. Ocado has also recently expressed its interest in autonomous vehicle technology for self-driving vans through a $13.8 million investment in autonomous vehicle technology company Oxbotica. The use of drone technology for deliveries is now beginning to extend beyond large behemoths such as Amazon, to startups such as Manna in Ireland, trialling grocery and medicine deliveries with supermarket chain Tesco, which estimates the market to be worth £10 billion in the UK alone over the coming years. UK supermarket chain Asda, owned by US giant Walmart, is also planning to trial drone delivery using drone firm Flytrex.

It is clear that the field of automation and logistics must improve to meet the demand of the e-commerce market, and with that, many large companies are already developing new innovations to meet customers’ expectations. However, these will be supported largely by innovators, especially SMEs, that will need to carefully protect their inventions, to maintain a position for themselves in this growing ecosystem. It has been noted that numerous companies, including Heineken and Philip Morris, have had to adapt their IP strategies to reflect the explosive growth in e-commerce platforms. Increasing sales channels have also dramatically increased the number of cases of infringement. This increase in counterfeiting has been influenced by significant changes in supply chains and rapid digitalisation, and has led to a number of malevolent parties taking the opportunity to monetise on someone’s invention or design, resulting in significant seizures of counterfeit branded products, including masks[4]. To combat these issues, many brand owners are now looking to online tools to help monitor and track potential infringements and, where relevant, initiate enforcement actions. Heineken has indicated that it has moved to single user-friendly online tools that allow monitoring of all their brands across different platforms. Ultimately, a company’s brand and its brand assets will remain an important point for business leverage and revenue production moving forward. For those utilising e-commerce platforms, it is likely that there will be an increased level of cooperation and collaboration between brand owners and platform providers to detect infringement and discourage the sale of counterfeit goods. Moreover, in response to an increase in passing off any counterfeit products, companies that are successfully operating through e-commerce platforms have utilised trade mark and design protection across multiple jurisdictions, to both protect their brand and at the same time deter any potential counterfeiters.

Naomi Korn Associates is one of the UK’s specialists in copyright, data protection and licensing support services.

Mathys & Squire Consulting is an intellectual property consulting team that can support all businesses in capitalising intangible assets.

Naomi Korn Associates and Mathys & Squire Consulting are working in partnership across multiple industries to provide innovative consultancy IP support services.

[1] (UNCTAD, 2020, pp. Summary of adoption of E-commerce legislation worldwide)

[2] (The Commonwealth, 2020, pp. Trade, Oceans and Natural Resources Directorate of the Commonwealth Secretariat Leveraging, Digital Connectivity for Post-COVID Competitiveness and Recovery)

[3] (Fabeil, Pazim, & Langgat, 2020, pp. Journal of Economics and Business, The Impact of Covid-19 pandemic crisis on micro-enterprises: Entrepreneurs perspective on business continuity and recovery strategy)

[4] (International Chamber of Commerce, 2020, pp. Disruptions caused by Covid-19 increase the risk of your business encountering illicit trade risks)