As London hosts DSEI UK, one of the world’s largest defence trade shows, a look at how the patent system deals with matters of national security.

Each year, a very small number of patent applications are classified as secret and vanish into the patent system without trace, re-emerging perhaps only years later, if at all. What does that mean in practice? How can the idea of such secret patents be reconciled with the rationale for having patents? And can there continue to be a place for secret patents given the ways of modern innovation?

A not so secret history

Britain in the 1850s. The time of the Great Exhibition and the Crimean War. The government, having only recently set up the Patent Office, moves to halt publication of John Macintosh’s patent application for “Incendiary materials for use in warfare”, which proposes means for attacking the port at Sevastopol. The application is eventually allowed to publish, but only after the war concludes with a peace treaty. The appetite for secrecy having been whetted, the government soon passes an Act formalising the process of restricting publication of certain patent applications. And then for good measure establishes the first Official Secrets Act.

Secret patents (strictly, only ever applications) have existed ever since. Over the subsequent decades, restrictions were issued for various military innovations: artillery fuses, rifled ordnance, explosives and, somewhat alarmingly, mechanisms for synchronising a machine gun to fire through aircraft propeller blades. Later restrictions were applied to radar, atomic weapons and the hovercraft. We know of some of these secret patents because they were subsequently declassified. Many others have not been. Some perhaps never will be.

The usual reason given for preventing publication of certain patent applications was, and is, that they describe inventions which would be problematic for national security should they ever become public. This also prevented details of sensitive inventions moving abroad; no country would wish to cede a potential technological advantage to a foreign adversary. But another reason was that successive governments wanted to bolster their own national arms manufacturing industries.

This led to some friction between the Patent Office, which had initial access to the patent applications and insisted on maintaining inventor confidentiality, and the military, which wanted access to the inventions as early as possible.

Caught in the middle, inventors would sometimes be frustrated that commercial opportunities were lost because a patent had been classified. At other times patriotic (or commercial) offers of inventions would be ignored or rebuffed by the government. Compensation, when offered, was sometimes generous but not always.

All the while, the attitude to secret patents was evolving. World events influenced what was invented as much as what the government considered necessary to keep secret and for how long. The net effect tended to a ratcheting up of restrictions.

The 1930s saw arguments for abolition of secret patents entirely. Perhaps, it was argued, it would be more effective to publish all patent applications and so confuse adversaries as to what was actually being adopted. Or perhaps full disclosure would serve to suggest that there must be something even better being kept secret. Such thinking was scuppered by the onset of another world war, which prompted additional defence regulations, and the subsequent Cold War which saw a further tightening up of secrecy laws.

Once something makes it into law it can be difficult to remove. When the UK Patents Act was last fundamentally revised, in 1977, the Lords proposed removing security provisions from the Act altogether, only for the relevant sections to be promptly re-inserted by the Commons. “We can go on living with it for the time being,” was one legislator’s observation. And so we do.

Secret patents in practice

The process at the UK IPO for handling secret patents is governed by sections 22 & 23 of the UK Patents Act (1977), which allows for patent applications deemed “prejudicial to national security” to be withheld from publication. Not only the application, but the information disclosed within it. The process is both universal and unusual, in that all UK patent applications are subject to it, at least initially, but the latter stages are so rare that most patent attorneys are unlikely ever to encounter them.

Every patent application filed at the UK IPO – whether national, European or international PCT applications – is routed via “Room GR70”. There, one of a small team of patent examiners reviews the contents of the application and consults a document provided by the Ministry of Defence. In the vast majority of cases, patent applications proceed as normal. Very occasionally, however, an application takes a different path.

These applications are marked according to their perceived sensitivity (Official, Official Sensitive, Secret or Top Secret, with possible additional caveats) and subsequently searched and examined in the usual way, but otherwise, while the restrictions are in place, they remain in a form of patent purgatory: they cannot be published, so they cannot be granted.

While the decision to issue a secrecy direction lies initially with the UK IPO, ultimately it is for the government to decide whether or not to maintain it. Reviews are done periodically, but for the applicant the process is opaque; the restrictions may simply be lifted at any time.

Once a section 22 direction has been issued, the resulting restrictions are onerous and the overheads considerable. Patent attorneys require the relevant level of security clearance to work on such applications, and their offices need to be suitably secure. It is forbidden to communicate the content of the application to others without permission. Breaching the restrictions is a criminal offence, punishable by fine and/or up to 2 years imprisonment. Permission must be sought to discuss the subject matter for commercial purposes or for filing related patent applications abroad.

Unless the government sees fit to declassify a secret patent the restrictions remain in place, essentially in perpetuity. The only way to discharge the responsibility for keeping secret the related papers is to withdraw the patent application.

Secret patent technologies

The term “prejudicial to national security”, which determines which patents become secret, is not precisely defined. Some technologies (such as those relating to nuclear, chemical and biological weapons) are self-evidently problematic, but others become so as technologies and threats evolve. Previous concerns about IEDs are now worries about drones and AI. A partially redacted version of the list made public over a decade ago detailed over 40 categories of technology, some likely expected (“fighting vehicles”), some somewhat vague (“specialist surveillance devices”), others remarkably specific (“accelerometers of accuracy better than 10-3g”). The contents of the full list, however, are classified.

Despite the seemingly broad scope of the restricted technologies list, the bar for an application to be classified appears to be high. Even a brief search of a patents database will show many applications with an explicitly stated military purpose, albeit an applicant simply stating that an invention is of relevance to the military does not necessarily make it so. And some applicants, wary of the restrictions which might be imposed, deliberately avoid describing their inventions in ways which may result in their patent applications being classified.

Secret patents by numbers

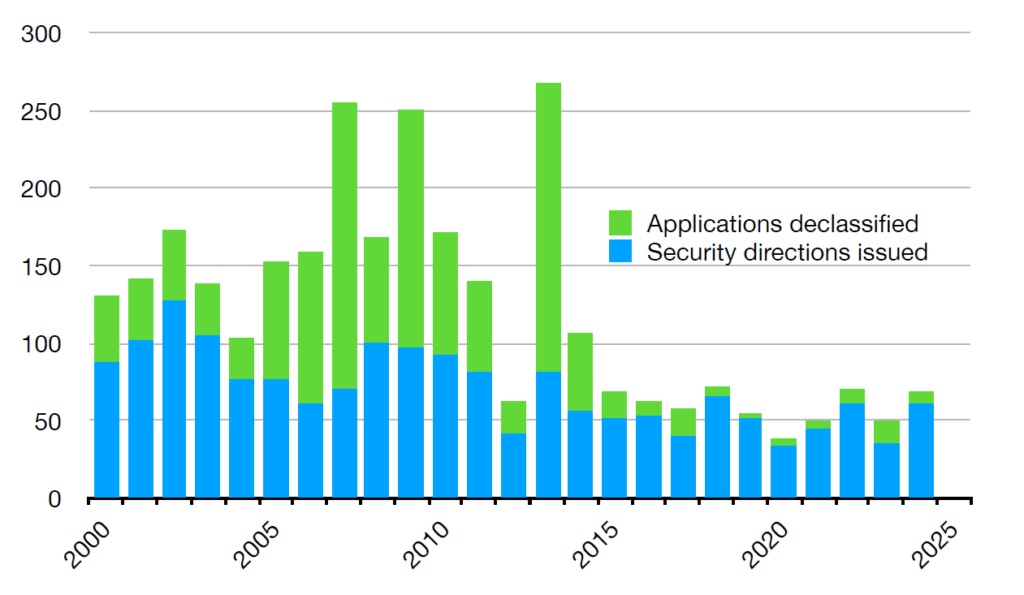

Inevitably, there is limited information on the number of secret patent applications. From the limited statistics reported by the UK IPO, it issues a secrecy direction on average once a week, a tiny fraction of the approximately 20,000 patent filings it handles each year (so unlikely to be a good metric for assessing the current state of innovation in the defence industry). Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of applications issued with such directions are filed by defence industry applicants, directly to the secrecy office.

Of all the patent applications filed since 2000, 1,755 were subject to secrecy directions, of which 1,100 of these directions remain in force. Meanwhile, 1,255 applications were declassified. The rate of declassification has evidently decreased sharply over the last couple of decades. However, since the total number of secret patents, including those which pre-date 2000, is not publicly known, it is unclear whether this decrease is because off an increased emphasis on secrecy or simply a result of fewer secret patents remaining to declassify. Restrictions on some particularly sensitive applications, such as those relating to the development of nuclear weapons, have reportedly been in place for over 80 years and are expected to remain so indefinitely.

The future of secret patents

Secret patents have a long history. But is there a place for them in the present world? The style and pace of military innovation has changed greatly since secret patents were first introduced. Barriers to entry are lower. There is less reliance on bespoke heavy engineering, more on software and AI. Many technologies are dual-use rather than exclusively military. What is proving most “prejudicial to national security” is now often based on commercial off-the-shelf products, many of which are cheap, easily available and able to be rapidly deployed in response to changing circumstances. Digital technologies have also allowed technology to be easily, widely distributed. There has been a democratisation of military technology. Innovation is (yet again) outpacing and side-stepping legislation.

So what purpose do secret patents serve? How effective have secret patents been in preventing the dissemination of technology? They are, in a sense, an attempt by governments to prevent genies from escaping their bottles. The list of proscribed technologies is very broad. There are very many bottles; is it realistic to expect to stopper them all? Historically, the significance of some inventions has been under-appreciated. In truth, while we may wish that certain inventions should not be widely available (see nuclear weapons), it is probably wishful thinking that they will remain so (see nuclear proliferation). Neither do secret patents prevent independent invention. Or espionage. What they do provide is a sense that a tide is being held back. More reassurance than reality.

Secret patents are an anachronism and are becoming increasingly irrelevant. They exist despite their inherent contradiction. The foundation of the patent system is a deal between the state and the applicant, wherein the state grants an exclusive, time-limited commercial rights in exchange for the public receiving a full description of how the invention works. Patents ostensibly exist to encourage the dissemination of inventions. Secret patents run counter to this ethos. Yet despite minor revisions over the years, and serious proposals to abolish the secrecy provisions altogether, secret patents persist. It seems we will need to go on living with them for the time being.

Sources

- Inventions and Official Secrecy: A History of Secret Patents in the United Kingdom, T. H. O’Dell,

Oxford University Press (1994) - UK IPO Facts and figures (2024)

- UK IPO Guidance Guidance: Technology prejudicial to national security or public safety