SpaceX is reportedly going public, in what may be one of the largest IPOs ever. What do we know about its patent portfolio? And what can we learn from its patent strategy?

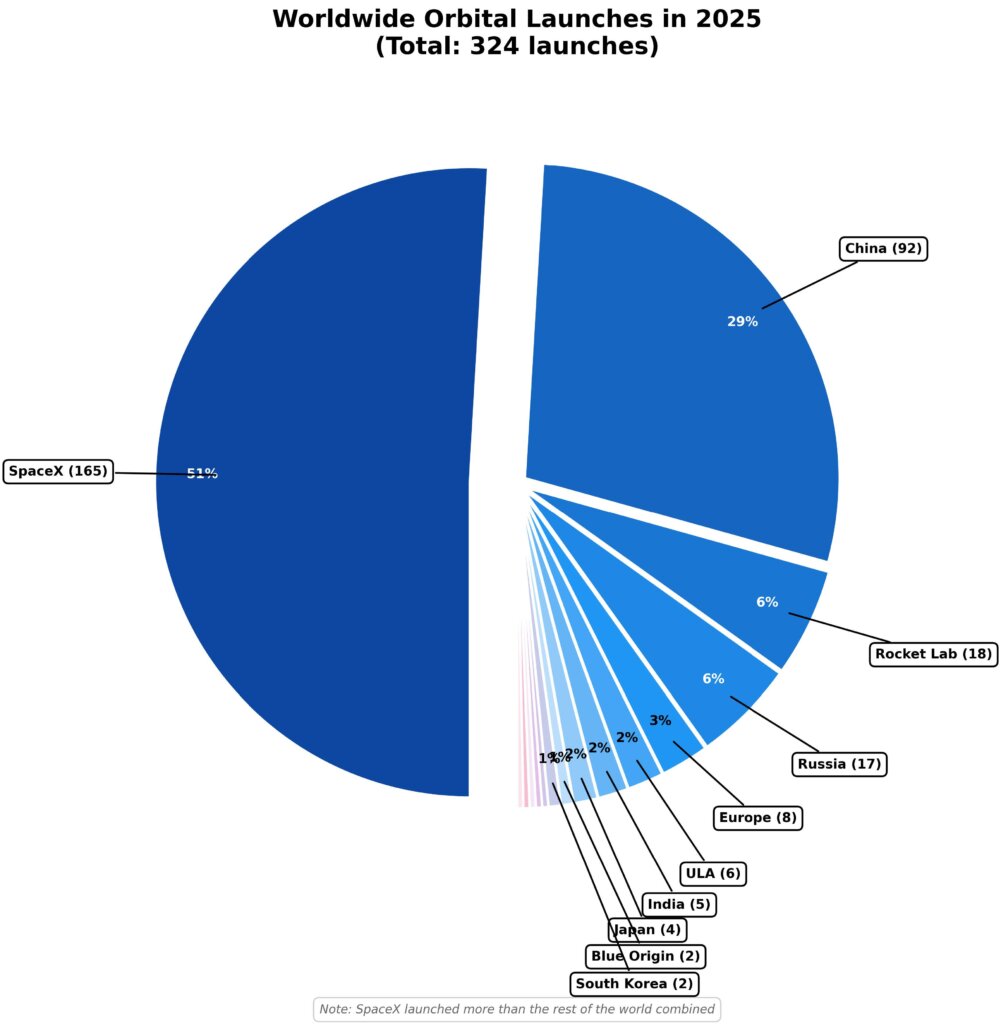

Since its founding in 2002, SpaceX has become the world’s dominant space company. The competition, for now, is not even close. Founded with the aim of significantly decreasing the costs of launching into orbit, saved from bankruptcy by the timely securing of generous government contracts to supply the international Space Station, SpaceX has been a media fixture with dramatic innovations, including the reusable Falcon 9 launch vehicle and the ‘chopsticks’ landing of its successor, Starship. SpaceX now averages 2-3 launches every week; in 2025, it was responsible for 50% of all orbital launches worldwide, 80% of ones in the US. These figures seem only likely to increase in the near term as even competitors find themselves relying on SpaceX to launch their satellites.

Now its CEO, Elon Musk, is said to be pondering taking SpaceX public. With an estimated valuation which has surged in the last year from $400 billion to $800 billion and some think could even reach $1.5 trillion, it would be one of the largest IPOs in history. What the billions expected to be raised from the sale would be used for is anyone’s guess. Some speculations are developing data centres in space to support the incessant demands of AI, aligning Musk’s other ventures xAI and Tesla for an anticipated convergence of AI and robotics technologies, or perhaps space manufacturing, and the stated ultimate goal: Mars. The plans would no doubt be grand.

SpaceX’s patent portfolio

SpaceX’s patenting strategy is perhaps not what one might expect; its patent portfolio

proves to be almost as idiosyncratic as its founder.

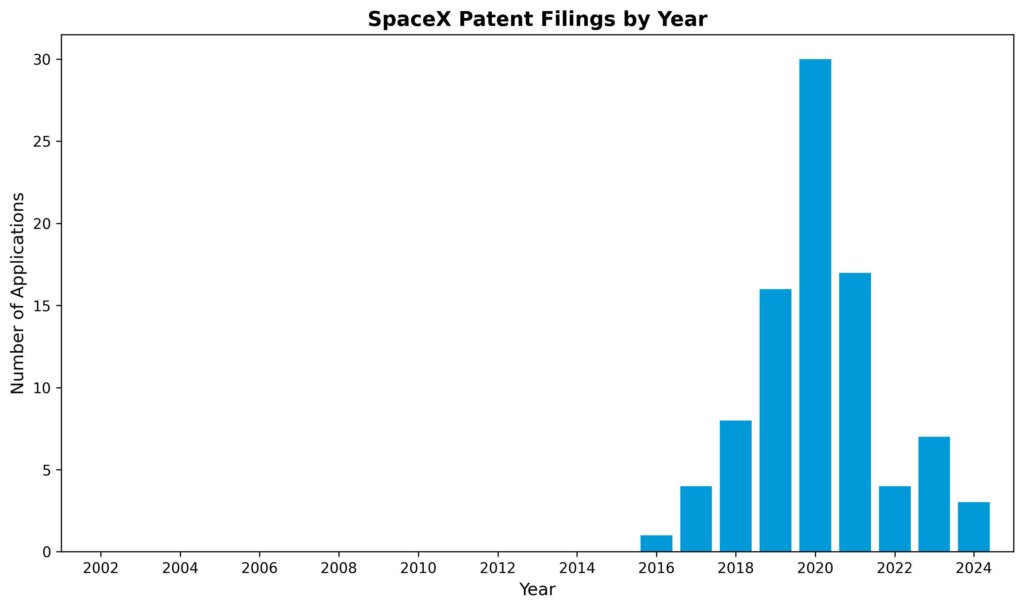

What is formally the Space Exploration Technologies Corp has a portfolio of nearly 100 distinct patent families. However, for over a decade of initial development SpaceX was not pursuing patent protection at all. Whatever the truth about Musk’s oft-quoted quip at the time that patents were “for the weak”, this position has evidently changed.

Why the change? Starlink. Since first launching in 2019, the wholly-owned subsidiary, with its constellation of now over 9,000 satellites providing internet connectivity worldwide, has itself grown to a dominant position, being responsible for two-thirds of active Earth-orbiting satellites. Starlink has been critical in providing SpaceX with a steady source of income.

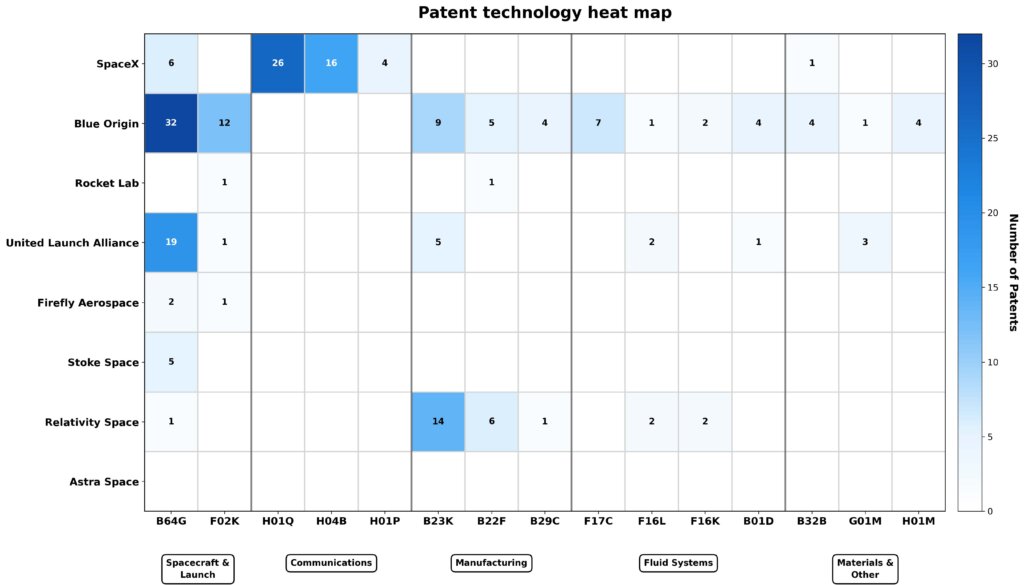

SpaceX’s patent filings now span various technologies relating to satellite communications, including antennas, printed circuitry, transmission systems and waveguides. This makes sense for technology implemented in widely available consumer products. There are even some design patents for the distinctive Starlink antennas. What is notably missing is any patent coverage for the launch systems themselves, whether for the rocket engines (Raptor, Draco), launch vehicles (Falcon, Starship) or spacecraft (Dragon).

A look at SpaceX’s competitors

SpaceX’s strategy is at odds with its launch start-up competitors, of which there are increasingly many. The burgeoning commercialisation of space has led to a flurry of space start-ups developing launch capability, at least two of which – Jeff Bezo’s Blue Origin and Rocket Lab – feature in the worldwide top-ten of launch providers (ULA, the United Launch Alliance, is actually a joint-venture between established aerospace giants Lockheed Martin and Boeing). Launching into orbit is no longer the exclusive provision of nation states.

When we compare the subject matter of patent filings, we find these competitors – Blue Origin in particular – are seeking patent protection for a broad range of launch-related technologies, including manufacturing, fluid systems and materials. Not so SpaceX, which has focused exclusively on Starlink.

Mapping SpaceX’s patents

Another curiosity is where SpaceX file for patents. As would be expected for a US-based company (and all SpaceX employees are required to be US citizens), initial patent applications are filed in the US. However, interest in patent rights beyond the US is very limited: only a dozen international applications, barely a third of the portfolio pursued elsewhere, essentially only in Germany and Taiwan. This is a highly geographically targeted patent filing strategy: protection for where there is relevant

The lack of patent protection beyond the US suggests perhaps some confidence at SpaceX that any non-US companies will not become commercial competitors within any realistic timescale, even allowing for the maximum 20-year patent term.

An evaluation of SpaceX’s patent strategy

While we can only speculate as to why SpaceX has avoided seeking patent protection for what might be considered its core technology, the lack of a comprehensive patent portfolio adds to the difficulty of assessing the long-term worth of SpaceX. In the near-term, Starlink appears to be more valuable on account of its steady income stream. Yet it is the launch capabilities which are the crown jewels and those appear to be unprotected by patents.

Admittedly, patents directed to the launch systems may be difficult to enforce, especially once launch has occurred and it becomes difficult to secure physical evidence of any infringement. Also, the applicability of patent law in space is not always clear. While the US has amended its patent law to supposedly extend to space, many other countries have not.

A more prosaic reason comes from another Musk quote, that he does not want to provide a “recipe book” for competitors, referencing China specifically; patent specifications require a full disclosure of the pertinent technical details.

Instead, SpaceX appears to protect its IP in launch technology via trade secrets. This comes with its own risks.

Although some SpaceX employees have over a decade of service, a demanding work schedule and culture differences (and despite financial incentives to stay and disincentives to leave) mean turnover rates for those with up to 5 years of experience are high. Employment contracts may have strict IP protections provisions, but know-how and experience may nevertheless simply walk out the door. SpaceX employees would be highly valuable elsewhere, including at legacy aerospace companies.

The spectre of industrial espionage also looms large, something of which SpaceX are evidently concerned: a Russian cosmonaut was recently removed from the SpaceX crew for allegedly photographing a rocket engine and other sensitive material with a smartphone.

The future of SpaceX

Imitation, the sincerest form of flattery, is now a realistic possibility. Several commercial competitors in China, such as LansSpace, have been testing launch vehicles which appear remarkably similar to those of SpaceX. The lack of formal IP protection there leaves everything open to copying.

Starlink, too, is not immune from competition. Others are sensing commercial opportunities; nation states do not want to become reliant on a single provider led by a mercurial CEO. Both are deploying constellations of their own: Amazon with its Kuiper and TeraWave; China (which blocks Starlink) has SpaceSail. Even Europe is getting in on the act with OneWeb. Such is the number of LEO satellites planned that there are genuine concerns that the Kessler Syndrome, where the amount of space debris that makes certain orbits unstable, will become a reality.

The risk to SpaceX’s dominance is clear. And there is form: Tesla is no longer the world’s largest electric vehicle company; BYD is.

Final thoughts

What can we conclude? That for a technology company patents are only one tool. It is entirely possible to operate with a hybrid approach: patents to protect income streams, especially if dependent on technology which is straightforward to reverse-engineer, geographically targeted at potential rival manufacturers; trade secrets for core technology which may be difficult to protect anyway.

There is another reading. SpaceX is sui generis. Whether its patent strategy can be used by other companies is unclear. Few companies can draw on the Musk celebrity which is an intrinsic part of the way SpaceX operates. But technology leads are not eternal; many once ubiquitous companies – Kodak, Blackberry, perhaps now Intel – have found themselves losing their way and being overtaken. Likewise SpaceX’s lead, which may at present appear unassailable, is likely only temporary. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why SpaceX might be going public sooner rather than later.