This article had been covered by IP Fray Law360 and World IP Review (WIPR).

On 21 November 2023, Mathys & Squire lodged a request under Rule 262.1(b) of the UPC’s Rules of Procedure requesting that the Court make available all written pleadings and evidence filed in relation to a case between Astellas and Healios KK. Finally, on 4 November 2024, over 11 months later, the UPC court have ordered that Mathys & Squire should have access to the pleadings as requested in unredacted form.

Public access to pleadings and evidence filed with the UPC registry is written into the Unified Patent Court Agreement with Article 45 UPCA promising that proceedings “shall be open to the public unless the Court decides to make them confidential, to the extent necessary, in the interest of one of the parties or other affected persons, or in the general interest of justice or public order.”

The extensive delays in granting Mathys & Squire access to court documents demonstrate the extent to which this promised public access in anything approaching a reasonable timescale has proven illusory in relation to ongoing cases as the following timeline of the case demonstrates.

| 21 Nov 2023 | Mathys & Squire files public access request |

| 12 Dec 2023 | Court issues preliminary order informing parties of an intention to suspend the application pending a decision in Ocado v Autostore appeal |

| 28 Dec 2023 | Case suspended pending a decision in Ocado v Autostore |

| 10 Apr 2024 | Ocado v Autostore decision issues – case restarts |

| 1 May 2024 | Mathys & Squire provide Court with comments on Ocado v Autostore |

| 22 May 2024 | Court sets 5 June deadline for parties’ responses |

| 5 Jun 2024 | Astellas provides comments on Ocado v Autostore appeal |

| 19 Jun 2024 | Astellas and Healios KK inform Court of out of court settlement |

| 24 Jul 2024 | Court publishes an order confirming settlement of underlying proceedings and sets date of 16 August for parties to comment on access request if Mathys & Squire confirm that the access request is maintained |

| 22 Aug 2024 | Court orders Mathys & Squire to be provided access to the court documents subject to redactions requested by Astellas and additional redactions imposed by Court |

| 12 Sept 2024 | Copies of redacted documents provided to Mathys & Squire |

| 1 Oct 2024 | Mathys & Squire files a request to have Astellas’ redactions removed |

| 3 Oct 2024 | Mathys & Squire files request for Court to provide copies of unpublished orders referred to in the case |

| 17 Oct 2024 | Mathys & Squire files request for Court to remove erroneous Court-imposed redaction and provide copies of erroneously omitted documents |

| 4 Nov 2024 | Court orders Astellas’ redactions removed, provides missing documents and removes erroneous Court redactions |

When access to the pleadings was initially granted in September, the documents were subjected both to redactions that had been requested by Astellas’ representatives and those imposed by the Court.

Review of the documents revealed that some documents filed during the case had not been provided to us. Indeed, those documents were not listed in the electronic case management system and their existence only became apparent because they were referred to elsewhere in the pleadings. Review of the documents also revealed that many of the redactions imposed by the court were inconsistent, unnecessary and clearly went beyond those necessary in the interests of any of the parties or the general interest of justice or public order.

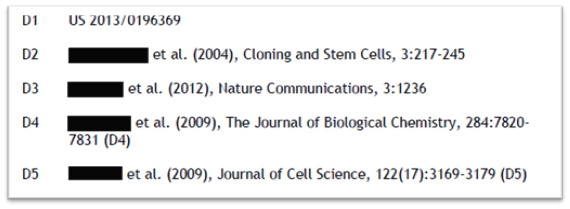

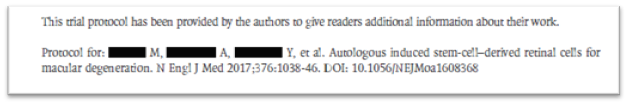

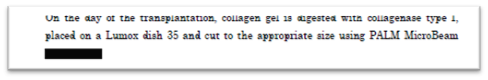

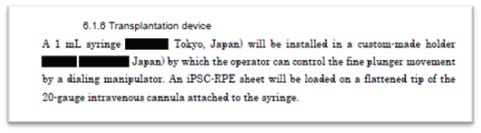

Examples of some of the more bizarre redactions imposed by the court included redactions of names of commercially-available laboratory equipment and reagents, standard experimental protocols, arbitrary portions of headers, figure labels and tables of contents. Titles of academic papers cited as prior art and identified by the names of their authors had also been randomly redacted, as had routine publicly-available information such as the names of inventors and public officials, and random portions of electronic signature blocks. In many cases redaction had been inconsistent, with the same information being redacted or not redacted in different copies of documents provided by the Court.

Examples of this highly inconsistent approach to redaction are illustrated below.

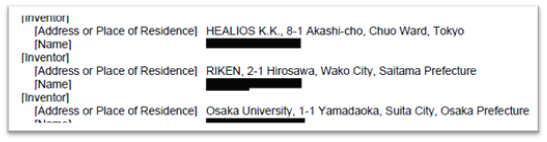

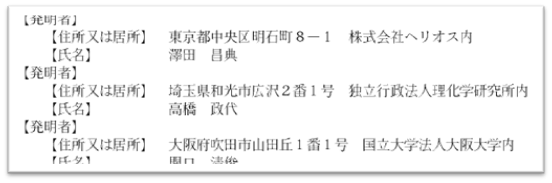

A). Inventors’ names redacted from translation of priority document while left unredacted in Japanese original in copy provided by Court

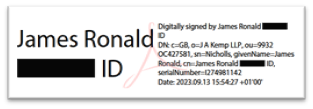

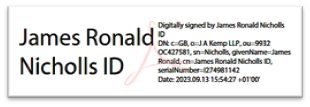

B). Two versions of a signature block included in a document provided by the Court multiple times – one with redactions, a second where the Court considered that redactions were not necessary

C). Examples of Court redactions of titles of prior art documents

D). Random redaction of names of laboratory equipment manufacturers from documents provided by Court

E). Partial redaction of figure labels in a publicly-available prior art document

It also appeared from the redactions that the Court intended to keep the identities of the parties’ expert witnesses confidential; however, this objective was defeated by the fact that the witnesses’ names were visible in the filenames given to their witness statements as listed in the case management system.

In addition, reading through the documentation, it was apparent that the pleadings and evidence referred to multiple Court orders which, contrary to the UPC Rules of Procedure, had not been published.

Further correspondence with the Registrar has revealed the causes of some, but not all, of these errors.

Apparently, the Court uses an anonymization tool which should theoretically only redact personal information present in pleadings and evidence. However, as is evidenced by the above, this tool is unreliable and information is misidentified leading to errors. Only by making a further application to the Court could (some of) these erroneous redactions be removed.

The Court’s failure to publish court orders as required by Rule 262.1(a) of the Court’s Rules of Procedure, which states that “decisions and orders made by the Court shall be published”, arises due to a conflict between this rule and Rule 34.2 (c) of the Rules Governing the Registry of the Unified Patent Court. That rule imposes on the Registrar an obligation to ensure that the UPC website contains a “collection of the final decisions and orders of the Court of general interest, as well as any corresponding translations of the headnotes and/or decisions in English, French and German”. This has been interpreted by the Court as limiting the decisions and orders which they need to publish. The hierarchy between the Rules of Procedure and the Rules Governing the Registry is not clear, but the Registry obviously considers itself to be bound primarily by the latter.

The practical effect of the Registry’s interpretation of the Rules is that it is incredibly difficult for third parties to monitor the progress of cases through the Court. Most of the orders the Court issues are orders specific to a case which would inform third parties regarding how a case is proceeding. But none of those orders ever see the light of day.

Regrettably, the Court’s Rules of Procedure place significant barriers on any third parties wanting to establish what is happening in a case before the Court. In February 2024, the Court interpreted its rules as requiring third parties wanting access to court documents to go to the expense of engaging representatives in order to file such requests. Since then, several divisions of the Court have taken (e.g. here, here, and here) a narrow view of the public interest in obtaining information about ongoing court cases and an expansive view of excluding the public from access to pleadings. These decisions are based on the grounds of the potential impact on the integrity of proceedings should members of the public actually obtain access to documents filed with the Court.

The Court took a very leisurely approach to progressing our access request, taking nearly a year to provide the requested documents. The result of the delays was that the case we wished to observe was settled before we obtained sight of any pleadings.

The Court’s erroneous redactions and the Registrar’s failure to comply with the Court’s orders then required us to make yet further applications to see the pleadings in full, as did a request by one of the parties to redact a portion of the pleadings, a request which the Court ultimately found to be unjustified.

Ultimately, the access request was successful. However, the extensive submissions required to obtain sight of the pleadings demonstrates the difficulties that third parties have in obtaining any information about disputes pending before the Court.