International Men’s Day is being held on 19 November 2024. The UK International Men’s Day team promote this day as an opportunity for us all to work towards shared objectives which are applied equally to men and boys irrespective of their age, ability, social background, ethnicity, sexuality, gender identity, religious belief and relationship status.

The six key pillars of International Men’s Day are:

(1) To promote positive male role models; not just movie stars and sports men but everyday, working class men who are living decent, honest lives.

(2) To celebrate men’s positive contributions; to society, community, family, marriage, child care, and to the environment.

(3) To focus on men’s health and wellbeing; social, emotional, physical and spiritual.

(4) To highlight discrimination against males; in areas of social services, social attitudes and expectations, and law.

(5) To improve gender relations and promote gender equality.

(6) To create a safer, better world; where people can be safe and grow to reach their full potential.

There are many aspects to men’s health and wellbeing, but improving men’s mental health is a particularly important goal. Although poor mental health does not discriminate between genders, approximately 75% of suicides in the UK are male. It has been suggested that work and financial pressures, feeling less able to talk about mental health, and outdated views of masculinity e.g., an expectation to be “tough” and being told to “man up”, are all contributing factors. Sadly, despite the clear need to support men’s mental health, only a third of NHS mental health referrals are for men.

Gardening has recently been used to improve mental health in the UK. GPs are now starting to “prescribe” gardening to patients living with anxiety, depression, and loneliness. Patients are given a plant to look after and are invited to join local community gardening projects with other residents. GPs have acknowledged physical, mental, and emotional benefits from as little as two hours gardening a week.

There are many different types of gardening ranging from weeding, mowing the lawn, and deadheading in larger gardens, to maintaining window boxes and balcony gardens which are more common in cities. Speak to friends and neighbours and find out what grows well in your local area. Visit a local garden centre with a friend, colleague, neighbour or relative, and learn more about plants and how to look after them. Garden centres stock a wide variety of houseplants – some are suited to bright suntraps and sunny windowsills, and others prefer a shady corner or more humid environment. Some houseplants require more specialist care than others so be sure to ask for help if you need to.

Houseplants have been found to reduce stress. A recent study measured the blood pressure and heart rate of participants while either completing a short computer-based task or repotting a houseplant. The researchers observed lower heart rates and blood pressure for the group performing the repotting task.

Several research groups have investigated the effect of indoor plants on productivity and creativity. One study reported an increase in the productivity of college students performing a timed computer-based task when plants were introduced to the environment.

There are also many physical health benefits to gardening. For example, there have been studies that suggest the physical activity involved in gardening can reduce the risk of developing prostate cancer – a disease that is expected to affect 1 in 8 men at some point in their lifetime. Gardening can help with weight management and can reduce the risk of developing other conditions including type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Talk to friends and colleagues about your houseplants and share tips for looking after them. Share cuttings and recommendations for the best plants to grow. Some houseplants that are particularly good for propagating are spider plants, money plants, monstera, and pothos. If you have one of these and someone says that they like it or it looks like it is doing well, offer them a cutting.

Try different types of gardening and see what works best for you. Perhaps you like growing vegetables or flowers from seed – seeing something grow and mature. You could plant bulbs in the spring and watch them come up year after year and spread to different parts of your garden. Maybe you prefer buying little plants/seedlings and potting up containers and window boxes. If outdoor space is limited then try going to a terrarium workshop and making something for your desk.

Gardens can also help develop friendships and a sense of community and belonging. Get together with friends and family for a BBQ or picnic in the garden. Join a local allotment and meet other people interested in growing vegetables and cut flowers. Plant native flowers to encourage biodiversity and watch wildlife using your garden. For more information on community gardening groups in your area, check out the RHS community gardening directory.

Whatever space you have, big or small, outside or inside, make some time to encourage a relative, friend, colleague, or neighbour to enjoy gardening with you this International Men’s Day.

The Supreme Court has partially overturned the Court of Appeal ruling and has provided further guidance on what can amount to bad faith.

The Supreme Court has found that the Court of Appeal was wrong to reverse the decision reached by the High Court on bad faith but was correct in its decision on infringement.

The Supreme Court has found that:

- The High Court was correct in finding that seeking protection for a trade mark in broad categories without commercial justification to use the mark for all goods and services applied for can amount to bad faith. This is especially the case for anyone applying for the registration of marks “with the intention obtaining an exclusive right for purposes other than those falling within the functions of a trade mark, namely purely as a legal weapon against third parties”

It was found that “Sky had applied for and secured these registrations across a great range of goods and services which they never had any intention to sell or provide, and yet they were prepared to deploy the full armoury presented by these SKY marks”

- The Court of Appeal was, however, right to find that, on the basis of the narrowed specifications of goods and services, infringement by Cloud Migration service had not been established; but no error had been made in relation to a finding of infringement in respect of Cloud Backup service.

- Additionally, the EU Trade Mark Regulation (the “EUTM Regulation”) continues to have direct effect in the context of proceedings pending before a United Kingdom court designated as an EU trade mark court prior to the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020 (“IP completion day”).

This judgment warns applicants to avoid registering trade marks for goods and services they do not intend to use, or to create a ‘legal weapon’ or monopoly over a wide range of goods and services. The implications of this decisions could mean that existing registrations face cancellation actions if the proprietor cannot demonstrate that, at the time of application, there was a reasonable prospect of using the mark for all or some of goods and services covered by the registration. Going forward, Applicants should be mindful when drafting their specification to ensure it doesn’t expose their trade mark to a bad faith challenge.

A more detailed analysis of the judgement and its implications will follow.

Find a link to the judgement here.

Mathys & Squire Partners Martin MacLean and Rebecca Tew have recently been featured in an exclusive interview for Lawyer Monthly Magazine sharing their expertise on their strategies for trade mark and patent management.

Click here to read the feature.

This article had been covered by IP Fray Law360 and World IP Review (WIPR).

On 21 November 2023, Mathys & Squire lodged a request under Rule 262.1(b) of the UPC’s Rules of Procedure requesting that the Court make available all written pleadings and evidence filed in relation to a case between Astellas and Healios KK. Finally, on 4 November 2024, over 11 months later, the UPC court have ordered that Mathys & Squire should have access to the pleadings as requested in unredacted form.

Public access to pleadings and evidence filed with the UPC registry is written into the Unified Patent Court Agreement with Article 45 UPCA promising that proceedings “shall be open to the public unless the Court decides to make them confidential, to the extent necessary, in the interest of one of the parties or other affected persons, or in the general interest of justice or public order.”

The extensive delays in granting Mathys & Squire access to court documents demonstrate the extent to which this promised public access in anything approaching a reasonable timescale has proven illusory in relation to ongoing cases as the following timeline of the case demonstrates.

| 21 Nov 2023 | Mathys & Squire files public access request |

| 12 Dec 2023 | Court issues preliminary order informing parties of an intention to suspend the application pending a decision in Ocado v Autostore appeal |

| 28 Dec 2023 | Case suspended pending a decision in Ocado v Autostore |

| 10 Apr 2024 | Ocado v Autostore decision issues – case restarts |

| 1 May 2024 | Mathys & Squire provide Court with comments on Ocado v Autostore |

| 22 May 2024 | Court sets 5 June deadline for parties’ responses |

| 5 Jun 2024 | Astellas provides comments on Ocado v Autostore appeal |

| 19 Jun 2024 | Astellas and Healios KK inform Court of out of court settlement |

| 24 Jul 2024 | Court publishes an order confirming settlement of underlying proceedings and sets date of 16 August for parties to comment on access request if Mathys & Squire confirm that the access request is maintained |

| 22 Aug 2024 | Court orders Mathys & Squire to be provided access to the court documents subject to redactions requested by Astellas and additional redactions imposed by Court |

| 12 Sept 2024 | Copies of redacted documents provided to Mathys & Squire |

| 1 Oct 2024 | Mathys & Squire files a request to have Astellas’ redactions removed |

| 3 Oct 2024 | Mathys & Squire files request for Court to provide copies of unpublished orders referred to in the case |

| 17 Oct 2024 | Mathys & Squire files request for Court to remove erroneous Court-imposed redaction and provide copies of erroneously omitted documents |

| 4 Nov 2024 | Court orders Astellas’ redactions removed, provides missing documents and removes erroneous Court redactions |

When access to the pleadings was initially granted in September, the documents were subjected both to redactions that had been requested by Astellas’ representatives and those imposed by the Court.

Review of the documents revealed that some documents filed during the case had not been provided to us. Indeed, those documents were not listed in the electronic case management system and their existence only became apparent because they were referred to elsewhere in the pleadings. Review of the documents also revealed that many of the redactions imposed by the court were inconsistent, unnecessary and clearly went beyond those necessary in the interests of any of the parties or the general interest of justice or public order.

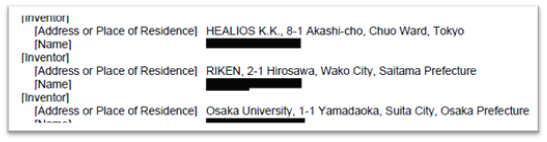

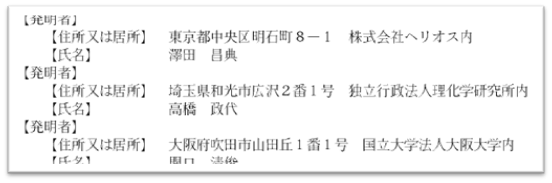

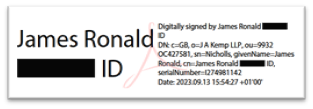

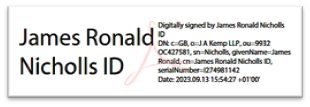

Examples of some of the more bizarre redactions imposed by the court included redactions of names of commercially-available laboratory equipment and reagents, standard experimental protocols, arbitrary portions of headers, figure labels and tables of contents. Titles of academic papers cited as prior art and identified by the names of their authors had also been randomly redacted, as had routine publicly-available information such as the names of inventors and public officials, and random portions of electronic signature blocks. In many cases redaction had been inconsistent, with the same information being redacted or not redacted in different copies of documents provided by the Court.

Examples of this highly inconsistent approach to redaction are illustrated below.

A). Inventors’ names redacted from translation of priority document while left unredacted in Japanese original in copy provided by Court

B). Two versions of a signature block included in a document provided by the Court multiple times – one with redactions, a second where the Court considered that redactions were not necessary

C). Examples of Court redactions of titles of prior art documents

D). Random redaction of names of laboratory equipment manufacturers from documents provided by Court

E). Partial redaction of figure labels in a publicly-available prior art document

It also appeared from the redactions that the Court intended to keep the identities of the parties’ expert witnesses confidential; however, this objective was defeated by the fact that the witnesses’ names were visible in the filenames given to their witness statements as listed in the case management system.

In addition, reading through the documentation, it was apparent that the pleadings and evidence referred to multiple Court orders which, contrary to the UPC Rules of Procedure, had not been published.

Further correspondence with the Registrar has revealed the causes of some, but not all, of these errors.

Apparently, the Court uses an anonymization tool which should theoretically only redact personal information present in pleadings and evidence. However, as is evidenced by the above, this tool is unreliable and information is misidentified leading to errors. Only by making a further application to the Court could (some of) these erroneous redactions be removed.

The Court’s failure to publish court orders as required by Rule 262.1(a) of the Court’s Rules of Procedure, which states that “decisions and orders made by the Court shall be published”, arises due to a conflict between this rule and Rule 34.2 (c) of the Rules Governing the Registry of the Unified Patent Court. That rule imposes on the Registrar an obligation to ensure that the UPC website contains a “collection of the final decisions and orders of the Court of general interest, as well as any corresponding translations of the headnotes and/or decisions in English, French and German”. This has been interpreted by the Court as limiting the decisions and orders which they need to publish. The hierarchy between the Rules of Procedure and the Rules Governing the Registry is not clear, but the Registry obviously considers itself to be bound primarily by the latter.

The practical effect of the Registry’s interpretation of the Rules is that it is incredibly difficult for third parties to monitor the progress of cases through the Court. Most of the orders the Court issues are orders specific to a case which would inform third parties regarding how a case is proceeding. But none of those orders ever see the light of day.

Regrettably, the Court’s Rules of Procedure place significant barriers on any third parties wanting to establish what is happening in a case before the Court. In February 2024, the Court interpreted its rules as requiring third parties wanting access to court documents to go to the expense of engaging representatives in order to file such requests. Since then, several divisions of the Court have taken (e.g. here, here, and here) a narrow view of the public interest in obtaining information about ongoing court cases and an expansive view of excluding the public from access to pleadings. These decisions are based on the grounds of the potential impact on the integrity of proceedings should members of the public actually obtain access to documents filed with the Court.

The Court took a very leisurely approach to progressing our access request, taking nearly a year to provide the requested documents. The result of the delays was that the case we wished to observe was settled before we obtained sight of any pleadings.

The Court’s erroneous redactions and the Registrar’s failure to comply with the Court’s orders then required us to make yet further applications to see the pleadings in full, as did a request by one of the parties to redact a portion of the pleadings, a request which the Court ultimately found to be unjustified.

Ultimately, the access request was successful. However, the extensive submissions required to obtain sight of the pleadings demonstrates the difficulties that third parties have in obtaining any information about disputes pending before the Court.

A recent report by the European Patent Office [1] has revealed that 10% of all inventions for which a European patent application has been filed are generated by university research conducted in Europe (measured in terms of number of patent applications filed at the European Patent Office).

The report is based on data collected between 2000 and 2020 featuring 1,200 European universities that have directly filed patent applications at the EPO, or that have university-affiliated researchers named as inventors on ‘indirect’ patent applications. Roughly two-thirds of the ‘university-generated’ patent applications fall into this ‘indirect’ category – i.e., the applications are filed by other entities such as small and medium-sized enterprises (including spin-out companies), not by the universities themselves.

The UK seems to perform consistently well, and ranks third for the total number of universities filing European patent applications per country, and number of academic European patent applications filed per country overall (following Germany and France). Of the 131 UK universities that filed at least one European patent application between 2000-2020, the University of Oxford is the UK’s leading institution, filing the most European patent applications of any UK-based university (1,660 in total). The average number of European patent applications filed by a UK-based university is approximately 100, but the data is heavily skewed: four universities filed over 1,000 patent applications each, and only six others filed between 300-1000 patent applications each. Of course, there will be differences in size and resources between universities, but some institutions may be missing opportunities to exploit and monetize university-generated IP more widely.

Statistics on applications made jointly by universities with a co-owner may shed further light on this skew in the UK data: in France, 79% of university-originating patent applications are filed with a co-owner, frequently a large public research organisation such as CNRS or INSERM. In contrast, only 10% of British universities file patent applications with a co-owner. Given the similarities between the sizes of the British and French populations and economies, one interpretation of this difference might suggest that UK university IP currently being left by the wayside could be unlocked by an enhanced role for UK public research organisations, such as the research councils or UKRI, in the commercialisation of research. Alternatively, smaller UK universities with limited resources could create shared technology transfer organisations to fulfil a similar role, as recommended in the UK Government’s recent independent review of university spin-outs. [2]

It is encouraging to see that UK startup businesses are particularly well-represented in the study. For example, 281 UK startups filed a total of 853 European patent applications relating to university-generated inventions between 2015 and 2019 (more startups and more startup-filed applications than any other country in the study).

In addition, four UK universities appear in the top eight academic institutions associated with startups that have filed patent applications to university-generated inventions: Oxford is joined by the University of Cambridge, Imperial College London, and University College London (perhaps unsurprisingly, the same four universities who filed more than 1000 European patent applications each across the study period). Indeed, the University of Cambridge is the second highest in this particular list (associated with 93 startups who filed European patent applications between 2000-2020) – just pipped to the post by ETH Zurich (101 startups).

Despite this success, the report comments on the “European paradox” and the difficulties of transforming advantages in academic research into applied technological and economic performance, compared to other advanced economies such as the US. The report suggests one reason for this is the difference in startup landscape between the US and Europe. The study also references Mario Draghi’s report on the future of European competitiveness [3] and Enrico Letta’s report on the future of the Single Market [4], which point to a fragmented innovation ecosystem across Europe as being central to Europe’s struggle to translate innovation into commercialisation. That 10% of startups with European academic patents are headquartered in the US (as reported in the EPO’s findings) highlights this struggle, as does Imperial College’s launch of a new science and tech hub in San Francisco [5]. Further emphasising the apparent ease of startup building and scaling in the US compared to Europe is Entrepreneur First (EF)’s recent development – whilst first launched in Europe in 2011, EF now requires all its startups to move to California for part of the EF programme and to officially incorporate their companies in the US. Changes to the innovation ecosystem are needed to retain startups using university-generated innovations in Europe.

To try and aid connections between potential investors and startups, the EPO Observatory on Patents and Technology has launched the Deep Tech Finder (DTF) [6], a digital platform designed to easily identify and analyse startups based within EPO member states that have filed European patent applications (and who may be seeking funding or business partners).

At Mathys & Squire, we understand that startup and scaleup businesses are at the frontline of innovation. We have expertise in supporting such businesses identify, protect and commercialise IP in every industry and sector. If you would like to find out more about how we can help you with your IP needs, please get in contact with our dedicated ‘Scaleup Quarter’.

[1] “The role of European universities in patenting and innovation”

[2] Independent review of university spin-out companies – GOV.UK

[3] EU competitiveness: Looking ahead

[4] Much more than a market report by Enrico Letta

[5] Imperial to strengthen Transatlantic tech cooperation with new hub

[6] Explore deep tech in Europe – EPO

About a year ago, the Enlarged Board of Appeal issued its decision in G 1/22 (consolidated with G 2/22), which significantly relaxed the EPO’s approach to ‘same applicant’ priority. Under the old approach, life could be tough: a priority claim was deemed invalid if a proprietor was unable to show, when challenged, that the applicants for the subsequent application included all of the applicants for the priority application or their successor(s) in title at the time the subsequent application was filed. Then the sun came out: the Enlarged Board held that there is a strong, rebuttable presumption that the priority applicants approve of the subsequent applicants’ entitlement to priority, regardless of any difference in names. See our earlier report here.

The CRISPR cases provide a striking example of this shift in the law.

Prior to G 1/22, Board of Appeal 3.3.8 upheld a decision of the EPO opposition division revoking an important CRISPR patent belonging to Broad, MIT and Harvard on the basis of intervening art that only became citeable because the subsequent applicants did not include one of the priority applicants or its successor title (and notwithstanding a plea from the proprietors for the EPO to take a more relaxed approach to ‘same applicant’ priority). See our reports of T 844/18 here and here.

Now, post-G 1/22, the same issue has come before Board 3.3.8 (albeit in a slightly different composition) in the context of a divisional of the revoked patent in case T 2360/19 (consolidated with T 2516/19 and T 2689/19, where the same issue also arose). How did the proprietors fare? Much better. The Board held that the omission of the relevant party from the subsequent application was of no consequence in view of the strong presumption in favour of priority entitlement. Essentially the same EPO tribunal with essentially the same set of facts before it came to the opposite conclusion on priority.

T 2360/19 is also noteworthy because of the Board’s finding that evidence of a dispute between the proprietors and the omitted party was not sufficient to rebut the strong presumption in favour of priority.

The dispute arose because the proprietors had filed the subsequent application (the PCT application from which the European family derived) without naming one of the priority applicants (Luciano Marraffini) or his successor in title (the Rockefeller University) on the PCT request form. The dispute was settled in 2018 by an arbitrator who decided that Marraffini should not be named as an inventor and Rockefeller should not be named as a proprietor of the PCT application. However, the opponents argued that the existence of the dispute proved there was no agreement on the transfer of priority rights belonging to Marraffini/Rockefeller.

The Board was of the contrary view – it saw the dispute as supporting the presumption of validity of the priority claim, because Marraffini and Rockefeller had wanted to be named in the PCT application, and therefore it was not credible that either of them would have acted in a way to invalidate the priority claim, particularly when the very purpose of the arbitration settlement was to safeguard the inventions made by Marraffini and others. The Board furthermore identified the settlement as an ex-post (retroactive) agreement on the transfer of priority rights, in line with the Enlarged Board’s suggestion in G 1/22 that the EPO should accept such agreements.

Interestingly, the settlement was not actually decisive to the outcome in T 2360/19 though. The Board held that the result would have been the same even in the absence of the settlement evidence, because “As also reiterated in G 1/22 … There is always a party who is entitled to claim priority, even if this party has to be determined in a national proceedings (with this being the same if the dispute is settled outside the courts, by way of amicable settlement or arbitration, as is the case here) … only the rebuttable presumption of a priority right guarantees that … this right is not ‘lost’ somewhere in an inventorship dispute.” The logic seems to be that, to the extent such a dispute has any bearing on the claim to priority of a patent, then the presumption is that the outcome of the dispute will entail preservation of the priority claim. This chimes with the Enlarged Board’s comment in G 1/22 that the EPC explicitly foresees the ex tunc assignment of priority rights in the context of disputes on the right to the patent before national courts, and that, in view of legal certainty, third parties can never fully rely on the invalidity of a priority claim.

What would it take to rebut the presumption that the subsequent applicants are entitled to claim priority? The Enlarged Board gave the example of party acting in bad faith. Thus, if evidence is provided that subsequent applicants filed a subsequent application without the agreement of a priority applicant or its successor in title, and that the priority applicant/successor does not and never did agree to the priority claim, then this might be enough to rebut the presumption. However, that is very different from the situation in T 2360/19, where the proprietors filed a statement from Rockefeller after the arbitration was concluded confirming that the university had been aware that the other proprietors were filing a series of PCT applications on CRISPR technology based on an inventorship determination, and that the university agrees that the correct parties were named on those PCT applications.

The case in T 2360/19 has now been remitted to the opposition division for examination of the other grounds of opposition. The decision, and that in each of the other consolidated cases, is likely to have broader significance for the proprietors though, because they omitted Marraffini/Rockefeller from many other PCT applications that contain the same priority claims. Whether the proprietors fare well before the opposition division following remittal remains to be seen – Board 3.3.8 recently issued a preliminary opinion in which it found a lack of enabling disclosure in the priority application for a similar CRISPR patent belonging to the University of California and others, which the proprietors then self-revoked, as reported here.

Historically, women’s health has been greatly underfunded and under-researched. Nowhere is this gender-biased neglect more evident than in the research and clinical management of menopause symptoms. In response, World Menopause Day, held every year on 18 October, aims to raise awareness of the symptoms and impact of menopause and highlight the options available for supporting those going through the menopause transition.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines menopause as “the permanent cessation of menstruation resulting from loss of ovarian follicular activity”.

In the UK, the average age for menopause is 51. However, spontaneous (natural) early menopause affects approximately 5% of the population before the age of 45 whilst premature menopause, defined as menopause before the age of 40, occurs in approximately 1% of women. It has been estimated that over one billion women globally will be perimenopausal or postmenopausal by 2030 and nearly 50 million people are expected to reach menopause each year.

Whilst a natural part of ageing, menopause often has a significant impact on personal, social and professional quality of life. Alarmingly, research from the Fawcett Society indicates that 10% of women have left the workplace due to the symptoms of menopause whilst a 2019 survey found that three in five menopausal people were negatively affected at work.

Classic symptoms of menopause include hot flushes (vasomotor symptoms), mood changes such as anxiety and depressive symptoms, urogenital symptoms including sexual dysfunction, incontinence and urinary tract infections, disturbed sleep, impaired verbal memory and musculoskeletal pain. For many, these symptoms are severe and debilitating. Even those who do not experience severe symptoms are at risk of long-term effects including increased risk of cardiometabolic disease, diabetes, bone loss and cancers associated with increased abdominal fat (e.g., breast, colon and endometrial cancer).

Symptoms are likely underdiagnosed and undertreated. For many, hot flushes are the only symptom they attribute to menopause, meaning that other symptoms are left inadequately managed. Many are hesitant to ask for help in case their symptoms are dismissed by medical professionals as a normal part of ageing.

Nevertheless, pharmacological treatments are available. The gold standard treatment for menopause symptoms is hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which aims to replace hormones lost during the menopause transition (i.e., oestrogen and progesterone). However, patient confidence in the safety of HRT was severely damaged following the publication of the 2002 Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study and the 2003 UK Million Women Study (MWS) which first linked HRT to increased risk of blood clots and stroke and a small absolute increased risk of breast cancer respectively. The resultant decline in HRT prescribing cast doubt over the commercial returns within the women’s health sector. As such, pharmacological innovation for menopause treatment has largely been limited to novel combinations of oestrogen and progesterone (e.g. synthetic or bioidentical forms) and formulations optimised for different routes of administration (e.g., oral tablets, patches, suppositories, gels or sprays).

More recently, interest in the menopause market has been piqued by the success of novel nonhormonal therapies such as fezolinetant. This next generation of therapeutics stems from the research of neuropathologist Prof Naomi Rance, who identified a specific group of neurons in the hypothalamus (a part of the brain that controls body temperature) that become overactive and enlarged in the brains of menopausal people. However, whilst fezolinetant has been approved by the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and is currently available via private prescription, it is not yet available via the National Health Service (NHS).

Faced with “medical gaslighting” and a dearth of suitable therapeutics, tech-savvy women are increasingly taking matters into their own hands and turning to technology to ease their menopause symptoms; the result being a boom in the FemTech (“female technology”) industry and rich pickings for innovators.

A notable example is Vira Health’s Stella app, which aims to provide a personalised treatment plan (for example, cognitive behavioural therapy, sleep scheduling, pelvic floor exercises) based on specific symptoms, machine learning, and lifestyle preferences. Devices aimed at relieving the symptoms of hot flushes include the Menopod, which was featured on an episode of Canadian Dragons Den, and the Thermaband Zone.

In such a rapidly growing market, innovators would be wise to develop a strategy for protecting and exploiting their intellectual property at an early stage. If in doubt, your patent attorney will be able to guide you.

In a surprise move, the representatives acting on behalf of UC Berkley defending CRISPR patents in appeal proceedings before the EPO have withdrawn their approval of the texts of the patents thereby revoking them and bringing the appeal proceedings to an end. When doing so, the representatives justified the withdrawal referencing “serious procedural concerns” arising from the Board of Appeal handling of appeal T2229/19, a decision Mathys & Squire are seeking to reverse through an application for Petition for Review.

In T2229/19 a Board held as inadmissible a request to delete two dependent claims solely on the grounds that although the deletion would have addressed all the objections considered so far, the deletion would not prima facie overcome the Board’s preliminary opinion on a different, yet to be discussed issue, namely sufficiency of disclosure.

In the CRISPR appeal, UC Berkely’s representatives concluded that given that the chairperson and rapporteur in their appeal were also members of the Board in T2229/19, the risk that the Board would adopt a similar approach in their appeal was such that the Patentees could not “be expected to expose the Nobel-prize winning invention protected by the … patent[s] to the repercussions of a decision handed down under such circumstances, when other members [of the patent family were] still at a stage where the Patentees [could] ensure that they [would] ultimately be fully heard on all substantive issues.”

It is highly unusual for a patentee to withdraw their approval of the text of a patent during appeal proceedings and accompany such a withdrawal with an expansive statement as to why a patent is valid and why the patentees have concerns about the expected handling of a case by a Board of Appeal.

It could well be that UC Berkley were merely providing cover for a withdrawal which will significantly delay the EPO making a final ruling on the validity of a patent. Certainly, that was the view of the representatives of the opponents who described the withdrawal as “a transparent move to avoid any possibility of an adverse decision” which they claimed was “justified by a (spurious and hypothetical) concern about the future conduct of the Board.”

However, if UC Berkley’s concerns are to be taken at face value, they raise serious questions about the EPO Boards of Appeal and in particular the Rules of Procedure which were introduced in 2020.

Those Rules of Procedure sought to emphasise that EPO Appeals should be restricted to a review of the proceedings at first instance and reduce the extent to which new matters might be raised on appeal. However, it is evident, that in some areas this has led to inconsistencies in approach. In our Petition for Review we noted that two distinct approaches [1] to the deletion of dependent claims during appeal proceedings (neither of which had been followed by the Board in that case) had arisen.

UC Berkely noted that our Petition for Review against T2229/19 could be pending for quite some time. Although the Petition for Review procedure was intended to be as simple and short as possible and prior to 2020, Petitions for Review were typically resolved in around 10 months, evidently that is no longer the case as was clearly demonstrated with the four-and-a-half year time period taken to resolve the Petition for Review in R1/20 which was finally resolved in July this year.

In the meantime, even though a Petition for Review is pending against it, T2229/19 serves as a potential precedent to be followed in other EPO Appeals and indeed recently another EPO Board of Appeal in T172/22 referred to T2229/19 as a precedent for refusing to allow claims to be deleted during appeal proceedings.

When Board of Appeal decisions result in the filing of Petitions for Review and cause the withdrawal of high-profile appeals, the apparent inability of the EPO to rule on such Petitions in a timely manner is very concerning.

[1] T1480/16 vs T1224/15

Partner Nicholas Fox has been featured in the ‘’This is a big problem’: The CRISPR controversy and the ‘mess’ at the heart of the EPO’s appeals boards’’ article by Sarah Speight published by WIPR and LSIPR discussing a request by CRISPR scientists to withdraw their patents over allegations of mishandling by the EPO’s Board of Appeals has thrust a ‘’fundamentally unfair, uncertain system’ into sharp focus.

Here is a short extract from the articles:

‘’…It’s seriously unusual for one set of patent attorneys in another set of proceedings to refer to another case in the way that they have done,” says Mathys & Squire partner Nicholas Fox, who filed the Ipsen complaint…

….”The fundamental issue here is discretion,” he adds. “It’s the discretion of the board, and it’s causing [problems], particularly for amendments or later amendments’’…

This article was first written for and published in WIPR and LSIPR on 27 September 2024. Please visit WIPR and LSIPR to read the full articles.

The UK remains highly ranked in terms of global innovation, but is the UK’s science and technology scene missing a trick when it comes to optimizing value for their innovations through international patent protection?

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) recently published the 2024 edition of its annual report of the Global Innovation Index, ranking world economies on various metrics considered pertinent to fostering innovation. Although the UK was overtaken by Singapore in this year’s edition, it remains highly innovative at a respectably 5th overall rank. Switzerland, Sweden and the United States maintain their top three overall ranks of the 2023 edition.

A recent report by the Chartered Institute of Patent Attorneys (CIPA), based on the 2023 edition of the Global Innovation Index, has however highlighted the UK’s relatively lower ranking on metrics related to international patenting activities. The UK ranks 19th and 20th in the number of multi-jurisdictional patent family filings and in the number of PCT application filings, adjusted for purchasing power parity GDP, respectively. This is well below the economies ranked higher overall in the Global Innovation Index (i.e. Switzerland, Sweden, the United States and Singapore), and is also behind comparable economies such as Germany, France, the Netherland, South Korea or Japan.

The benefits of geographical diversification over a patent strategy focussing only on a single country can be significant. Protection in several key jurisdictions allows increased value to be derived from a patent portfolio, be it in the form of a competitive edge in a larger overall market or in the form of increased revenue obtained by licensing patent rights across different regions. Competitors are deterred more effectively from challenging a patent in view of the increased potential costs and legal risks of multi-jurisdictional litigation. In addition, investors may place increasing value on multi-jurisdictional patent families, thus elevating the valuation of a business.

Why British businesses, despite their high capacity for innovation, pursue international patent protection at a lower rate than businesses in competitive economies remains an open question. CIPA’s analysis shows that the lower number of overseas filings by UK applicants may well be attributed to lower rates of filing at the European Patent Office (EPO) and in China. Given that EPO member states and China make up a significant proportion of British export markets, these lower rates of filings are surprising.

Ultimately, the number of jurisdictions in which to pursue patent protection remains a business decision. While it is not pragmatic in most technology areas to file in tens of jurisdictions, a focus on several key jurisdictions may elevate the value derived from innovation and ensure that business interests are well protected in an increasingly globalized economy.