On Wednesday the 25th of June 2025, Mathys & Squire hosted Dr Victoria McCloud, former Judge in the High Court and advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights, in our London office in honour of Pride Month.

From a young age, Victoria discovered a fascination with computers, as well as an acute awareness of human behaviour and interactions – experiencing life through the eyes of a girl as a registered boy at birth. These interests motivated her to pursue a degree in Experimental Psychology and a doctorate in the computational aspects of human vision.

After graduating, she practiced as a barrister, when she came out as a transgender woman, and then went on to be the youngest and first (and only) transgender Master in the UK High Court of Justice.

In 2024, she resigned as a Judge, feeling that there was no longer a place for her as a trans person in the UK court. Now, Victoria McCloud is a freelance public speaker, author and media commentator, raising awareness for issues affecting the LGBTQIA+ community and speaking directly from her experience as a trans woman.

Last year, she featured on the Dow Jones News “Pride of Finance”, whilst this year she reached first place in the Independent Newspaper Pride List and featured in Attitude Magazine’s 101 LGBTQ+ trailblazers 2025.

Victoria gave an educational and engaging talk which followed the timeline of her life whilst delving in to important topics, such as the nature of the UK legal system, changing attitudes towards gender, and her recent move to the “rainbow paradise” of Ireland. She also discussed the topical issue of how the rights of transgender and gay people are under threat in light of the recent Supreme Court Ruling. It was enlightening to gain an insight from someone with a deep understanding of both the law and the trans experience.

We are delighted to announce two new Partners and two new Managing Associates.

Mathys & Squire is delighted to announce a new round of senior promotions to its London office.

Harry Rowe and Dylan Morgan have been appointed as Partners. Helen Springbett and Tom Bosworth have been promoted to Managing Associates.

These appointments recognise their valuable contributions and leadership across Mathys & Squire’s trade mark, design and patent teams.

Harry Rowe is appointed Partner in London

Harry has over a decade of legal expertise specialising in trade mark law issues facing multinational corporations and SMEs. He works across a range of sectors including financial services, life sciences and automotive. Harry has a proven track record handling disputes, prosecutions and enforcement, including litigation. He is a recommended lawyer in the latest edition of The Legal 500.

Dylan Morgan is appointed Partner in London

Dylan has considerable experience drafting and prosecuting UK and European patents, managing global portfolios, and advising on infringement, licensing and IP strategy. He was previously an engineer at the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory. Dylan holds a master’s degree from the University of Cambridge, specialising in aerospace engineering.

Helen Springbett is appointed Managing Associate in London

Helen has extensive experience in patents and designs, specialising in the physics, mechanical engineering and materials science sectors. She has a wealth of expertise in medical informatics and devices, mechanical devices and nanotechnology. Helen holds a PhD in materials science from the University of Cambridge, specialising in the characterisation of quantum dots.

Tom Bosworth is appointed Managing Associate in London

Tom has significant experience in patent drafting, prosecution, and EPO oppositions and appeals. He specialises in cell and gene therapy, vaccines, antibodies, and genomics technologies. He holds a PhD in cardiovascular sciences from the University of Manchester. Tom previously worked in the biotechnology industry prior to his PhD.

Martin MacLean, a Senior Equity Partner at Mathys & Squire, says: “These promotions have all been well earned. Harry, Dylan, Helen and Tom are incredibly talented attorneys whose drive and hard work are an immense asset to our firm.

“We take pride in nurturing and developing our talent, and all four have consistently delivered the highest-quality work to our clients. I’m fully confident they will continue developing their practice and enhancing their expertise.

“We are very excited to welcome Harry and Dylan into our Partnership. Both will help lead our firm on a strategic level and play a crucial role in our growth plans.”

This press release has been featured in Law360 and New Law Journal.

This June marks Pride month, a time to celebrate the talent, creativity and innovation demonstrated by members of the LGBTQIA+ community, and reflect on the challenges and discrimination many would have faced particularly in their professional careers.

Whilst there has been progression over the years, it is no secret that we still live in a time where many are unable to feel empowered as their authentic self. Therefore, by acknowledging the following engineers and technical experts, we not only honour their scientific contributions, but also highlight the importance of visibility and representation. The following people serve as powerful role models to the next generation, inspiring and empowering others to pursue their ambitions with confidence and pride.

Frank Kameny (1925-2011)

Frank Kameny had a passion for astronomy from a young age, majoring in Physics in his degree at Queens College and completing his PhD later at Harvard University. He worked for the Army Map Service, working to develop and analyse astronomical maps during the conflict between the Soviet Union and the US. Unfortunately, he was fired shortly after it came to their attention that he identified as gay, and with his security clearance removed, he was no longer able fulfil this passion. In 1961, he became the first to petition the Supreme Court with a discrimination claim based on sexual orientation, and committed to being a LGBTQIA+ activist, organising protests and assisting others with their discriminatory law suits.

Sally Ride (1951-2012)

On 18 June 1983, Sally Ride became the first American woman to travel to space, as she completed her journey on the Challenger’s STS-7 mission. Beyond her vital work at NASA, she founded Sally Ride Science, a non-profit organisation which encouraged women to pursue STEM subjects. Sally had preferred to keep her identity as part of the LGBTQIA+ community private until after her death, in which she posthumously revealed that she had an intimate relationship with her working partner, Tam O’Shaughnessy. In 2013, the year after her passing, she was honoured with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama.

Edith Windsor (1929-2017)

In the 1960s, Edith Windsor was a pioneering computer programmer who exceeded in her career. She famously worked at IBM for 16 years, reaching the greatest possible position as a Senior Systems Programmer, a feat even more impressive as a woman in this era. She was an LGBTQIA+ activist and played a vital role in the Supreme Court case Windsor vs United States, in which she famously argued for a tax refund after the passing of her partner, which led to the court granting more benefits to same-sex couples. People often reference this as a turning point for same-sex couple in the US, and she is therefore remembered with the utmost respect. In 2013, she was a finalist for TIME magazine’s Person of the Year, and was described by TIME as “the matriarch of the gay-rights movement”.

Nergis Mavalvala (1968-)

Nergis Mavalvala is an astrophysicist who played a key role in the discovery of gravitational waves from the collision of two black holes. In his theory of general relativity, Albert Einstein had theorised this phenomenon, but it was Nergis and the rest of her team who were able to confirm this. Nergis has always been thoroughly committed to her education, completing her doctorate degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Astrophysics. She refers to herself as an “out, queer person of colour”, and dedicates herself to challenging discrimination in STEM.

Audrey Tang (1981-)

Audrey Tang is a computer scientist who first brought attention to their technological skill in 2014 during the Sunflower Protests in Taiwan as an open-source hacker, by helping to stream videos of the movement across the country. Tang later joined the ministry at 35, becoming the first ‘Digital Minister’ and Taiwan’s first transgender and non-binary minister. They have since been involved in revolutionary programmes, such as an educational initiative that helped equip young people with skills to identify fake news stories, as well as developing the ‘Mask Map’ during COVID-19, an online application which showed where masks were available to purchase during a national shortage.

At Mathys & Squire, we believe it is essential that everyone feels empowered to bring their full, authentic selves to work. We are deeply committed to fostering a workplace culture where diversity is celebrated, inclusion is prioritised, and everyone feels respected, valued, and supported.

Click here to read more about our Diversity & Inclusion policies.

IPSS Electra Valentine has co-written an article highlighting the meaning of Juneteenth as part of her role on the IP & ME committee at IP inclusive.

Yesterday marked Juneteenth, a significant day commemorating the end of slavery in the United States. It serves not only as a moment to celebrate freedom, but also an important opportunity to deepen our understanding of Black history, culture, and the ongoing journey toward equality.

The article examines the historical context of this day and considers its relevance and significance for IP professionals based in the UK, highlighting how its themes of freedom, justice, and inclusion resonate within the industry today.

Click here to read more.

We are proud to announce the appointment of Lyle Ellis as head of Mathys & Squire Consulting, the consulting arm of our firm.

Lyle joins Mathys & Squire from KPMG Law, where he served as Senior Manager in the IP Advisory division, advising startups and multinational corporations on IP strategy and operational management.

Lyle brings over 20 years of extensive experience in intellectual property management, strategy, and advisory services. Prior to KPMG, Lyle had a distinguished career as a UK and European Patent Attorney in-house at Vodafone.

Mathys & Squire Consulting advises clients on how they can maximise value from the intellectual property they produce and own. Specialist IP services within that group include IP audits, outsourced IP management, advising on contracts and licenses, and IP valuations.

Lyle brings a deep background in legal and commercial IP strategy, including IP risk management, threat assessment and value maximisation to Mathys & Squire Consulting.

His proven expertise in developing and managing IP portfolios will contribute significantly to the firm’s growth and capabilities, enhancing its ability to provide clients with high-quality, strategic IP advice.

Alan MacDougall, a Senior Equity Partner at Mathys & Squire, says: “We are thrilled to welcome Lyle to the team. His unparalleled expertise in IP will strengthen our capabilities and accelerate our growth. His leadership will undoubtedly enhance our ability to provide exceptional service to clients.”

Lyle Ellis says: “I’m excited to join Mathys & Squire and work with its talented team of consultants and other IP specialists. Mathys & Squire has a fantastic reputation as a law firm and it is also doing some really innovative and important work in the IP consultancy field. I’m looking forward to working with the team to build on that growing track record.”

The Enlarged Board of Appeal has issued a decision confirming that the description and drawings shall always be consulted to interpret the claims when assessing the patentability (i.e. novelty and inventiveness) of an invention.

In their decision on case G1/24, issued on 18th June 2025, the Enlarged Board of Appeal heard facts and arguments concerning a worrying divergence which had occurred in the case law, whereby questions of claim construction and interpretation had sometimes been made with reference to the description and drawings, and other times in isolation of the remainder of the specification. Oftentimes, this difference depended on the clarity of the claims, with it being generally agreed that the description and figures could be considered if the claims were unclear or ambiguous but potentially not otherwise.

In this new decision, the Enlarged Board have rejected any premise that the resources of the patent which are available to assist in interpreting the claims may depend on the clarity of the claims themselves, stating that: “To regard a claim as clear is in itself an act of interpretation, not a prerequisite to construction.” Thus, the decision of the Board fundamentally changes the impact of claim clarity on the assessment of claim construction, harmonising the approach for all claims.

The Board’s decision also serves to harmonise the approach of the EPO with that of the UPC and European national courts, with the Board confirming that their decision was consistent with recent decisions of the UPC, and acknowledging a need and desire for further harmonisation.

This decision is likely to be broadly welcomed by many users of the EPC due to the certainty it provides as to the scope of the patent teaching which may be relied upon for claim construction purposes. By bringing the EPO approach into greater conformity with that of the UPC and national courts, the EPO also increases its ability to grant and maintain robust patents. Alongside these benefits, care should be taken to consider closely the impact of any amendments or differences that may have arisen between the claims and the description or figures of an application to ensure that undesirable constructions are not arrived at which may impact upon the scope and/or patentability of the claims.

If you have any questions as to how this decision may impact on your IP strategy, please reach out to your usual contact at Mathys & Squire, or get in touch through a general enquiry and we would be happy to help.

Clean energy beamed down to Earth. Exotic semiconductors and novel pharmaceuticals manufactured in microgravity. A base on the moon. Asteroid mining. Satellite recycling. Data server farms in orbit. Space tourists.

A new horizon study Space: 2075, issued by the Royal Society, sets out a vision of potential developments in space over the next 50 years. These could be as consequential, the report says, as the Industrial Revolution of the 18th century or the digital revolution of the 20th. But as space

becomes increasingly commercialised, is the present patent system up to the task?

The state of the UK space industry

The UK space industry is worth over £16 billion annually and employs more than 45,000 people. Almost every year since 2000 has seen the incorporation of at least 50 new space-related companies in the UK.

That said, the UK could do better. The UK spends less on space than some similarly-sized nations – less as a % of GDP than France, Italy, Belgium, Germany, as well as even Switzerland and Norway. Attempts to spur the industry have had mixed results. The UK has established over a dozen space innovation clusters, but none of the seven UK spaceports first legislated for in 2018 have as yet resulted in a successful launch.

Meanwhile, for reasons both geopolitical and economic, international competition in the space sector is increasing. National pride, industrial and defence policies have led to approximately a dozen countries now having launch capability. At the same time, the cost of getting material into orbit has fallen. In the last decade, the cost of launching a 1kg payload into low-Earth orbit has fallen from around £15k to £1k. This has consequently lowered a major barrier for new entrants.

It is clear that the UK space industry needs a boost. And indeed, the Royal Society report identifies the need to stimulate the scale-up of UK space SMEs. One recommendation for achieving this is through increasing the confidence of the finance sector. For example, using technical means to reduce the risk of satellite collisions could reduce insurance costs.

What is missing from the report is a discussion of another form of incentive: patents. Investors looking to back a company in an innovation-driven industry such as space will be wanting to know whether they have sufficiently protected their intellectual property to ensure successful commercialisation.

Patent law and the impact of ‘space law’

Here on Earth, most countries of the industrialised world operate a well-established patent system, the foundations of which can be traced back to the Paris Convention for the protection of industrial property of 1883. Although patents are inherently territorial, which is to say they operate at a national level, various international agreements have sought to allow for some degree of interoperability.

However, patent law becomes less clear above the Kármán line, the 100km altitude widely accepted as the beginning of space. Part of the problem is a certain tension between terrestrial patent law and what might be termed ‘space law’, originating in a handful of international agreements drawn up in the 1960s and 70s. The idealistic tone of these early agreements, seeking to codify the peaceful exploration of space, can be seen in how they constrain property rights. The agreements prohibit national appropriation in an attempt to ensure space remains the “common heritage of mankind.”

This is not to say that ownership of IP in space is entirely impossible. Much of the concern of these treaties was the ownership of physical rather than intellectual property. In other words, whether a nation, corporation or individual could lay claim to a celestial body (generally, no). It has subsequently been argued that the treaty language is ambiguous. For example, it is unclear whether it would apply to processed material extracted from such bodies by mining activities.

Who owns innovation beyond Earth?

There is potential for applying ostensibly Earth-bound laws, including those directed to intellectual property, in space. The potential arises from the way the Outer Space treaty (1967) and the registration Convention (1965) allow for jurisdiction over an object launched into space or on a celestial body to reside with the state which launches the body or the state from which the body is launched. Some later agreements, typically multilateral ones in respect of specific endeavours, acknowledge jurisdiction over IP more directly. For example, the ISS agreement (1998) includes specific provisions regarding protection of IP on the international space station, assigning jurisdiction and territory of each station module according to its state of origin. Others, such as the Artemis Accords (2020), merely acknowledge the need for relevant IP provisions without providing any further legal structure.

At present, in much the same way as an “international patent” does not exist, neither are there any provisions for – or immediate prospects of – a “space patent.” And while some countries, notably the US, have explicitly sought to extend the coverage of their national patent law to inventions made in space, many others including the UK have no such provision. This could arguably lead to the situation of a space object being considered to be in the jurisdiction of the UK by virtue of being launched from the UK, yet outside the territorial scope of UK patent law.

How can space innovations be best protected?

The applicability of patent law in orbit (or beyond) remains untested and proving infringement in space is unlikely to be straightforward. In the absence of specific contractual agreement, the best option at present appears to be, rather ironically, to aim primarily for terrestrial protection i.e. to seek a patent monopoly that would be infringed on Earth.

To that end, a careful analysis of what activities are being conducted on Earth needs to be undertaken. And for a product being made in orbit, where it is to be returned to on Earth.

The patent filing strategy also requires careful consideration, not least because territorial decisions made relatively early in the patenting process become locked-in for the duration. This requires due diligence to identify competitors: where relevant space objects are registered (the ‘flag of convenience’ issue) and launch locations both present and future.

So, can the present patent system cope with potential developments in space over the next 50 years? For the next short while, with careful handling, perhaps – but over the long term it seems some updates will be inevitable. The Industrial Revolution led to a substantial overhaul of patent laws; the digital revolution was accompanied by a flood of patent filings pushing the boundaries of patent laws. Would we expect the space revolution to be any different?

In celebration of our 115th anniversary, we are proud to have planted 115 trees in partnership with Trees for Life. Each tree symbolises a year of growth, resilience, and our continued commitment to building a better, greener future.

As we celebrate our 115th anniversary, we have a valuable opportunity to reflect on our history and acknowledge the people, milestones and moments that have helped shape our firm. It is also a time in which we can look ahead with purpose, recognising the vital role that we play in shaping a more sustainable world and promoting positive change for future generations.

At Mathys & Squire, we firmly believe that protecting the environment is not just a responsibility, but a necessity. Through initiatives like this, and through the continued integration of environmentally conscious practices in our day-to-day operations, we are committed to contributing to a more sustainable world.

Click here to find out more about our CSR initiatives.

World Environment Day, held each year on 5 June and led by the United Nations, raises awareness of the threats facing our planet — and what we can do to address them. In recognition of this day, we explore how the dream of limitless clean energy may be closer than we think. While solar and wind have laid the foundation, newer technologies like hydrogen and nuclear fusion are gaining momentum — and at the heart of their progress lies innovation and intellectual property (IP).

The growing pressure on power

Global energy demand is soaring — driven by the rise of electric vehicles, energy-intensive manufacturing, and the rapid expansion of AI, data centres and digital infrastructure. Electricity demand alone has grown at twice the rate of overall energy consumption over the past decade. By 2030, it is projected to rise by 6,750 terawatt-hours — more than the current combined usage of the US and EU. Data centres alone could account for 20% of that growth.

On top of this, electricity production remains the largest source of global CO₂ emissions. Without a rapid shift to cleaner energy sources, meeting climate goals over the next five to twenty-five years will be all but impossible.

A green transition underway

Fortunately, change is in motion. As we discussed in our 2025 Clean Tech Trends report, the renewable energy sector is accelerating. Global leaders — from policymakers to scientists — are striving to decarbonise the energy system while also tackling energy poverty, aiming to deliver clean, affordable power for all.

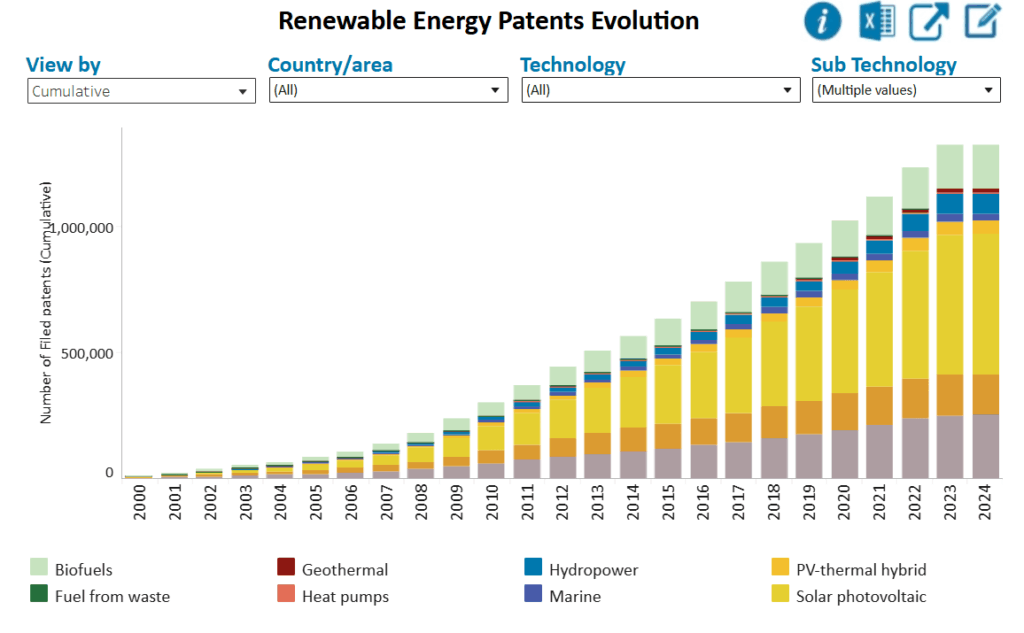

Solar and wind continue to dominate patent filings, accounting for 58% and 19% of renewable energy patents filed in 2024, respectively (See adjacent graph; source).

But despite their success, intermittent supply and grid strain limit their scalability. The question now is: what comes next?

Hydrogen: clean, flexible, scalable energy

Hydrogen is emerging as one of the most promising alternatives. Hydrogen fuel cells produce electricity by combining hydrogen and oxygen — emitting only water and heat. These cells can be integrated into existing infrastructure, making them highly adaptable.

Beyond cutting emissions, hydrogen offers an opportunity to decentralise power generation, which could ease grid pressure and benefit regions lacking reliable solar or wind resources. Companies like GeoPura argue that hydrogen could be the answer to both the AI energy boom and the electrification of transport, especially in the face of projected grid connection delays of up to 15 years.

Government and industry support is also growing. A 2024 white paper from Bosch, Centrica, and Ceres outlined hydrogen’s role in decarbonising UK power through solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs). And yet, a challenge remains: while hydrogen fuel cells are green, the hydrogen used to power them often isn’t. As of 2024, only around 1% of global hydrogen is produced via low-emission methods like electrolysis — the rest is derived from fossil fuels. Scaling up ‘green hydrogen’ production will be crucial.

Momentum is building. In 2024, the UK committed £2 billion to fund 11 commercial electrolytic hydrogen projects, attracting an additional £413 million in private investment. In the US, Electric Hydrogen is delivering a 100MW electrolyser system capable of producing 45 tonnes of hydrogen per day with minimal emissions. According to the International Energy Association’s Global Hydrogen Review 2024, annual production of low-emissions hydrogen could reach 49 Mtpa H2 by 2030, up from 1 Mtpa H2 in 2024.

The pace of innovation is clear — but sustained progress requires more than technology alone.

Fusion energy: approaching a breakthrough?

Looking ahead, nuclear fusion could become the ultimate clean energy source. By fusing light atomic nuclei — typically deuterium and tritium — fusion releases vast amounts of energy without carbon emissions. One gram of fuel can generate the same energy as 20 tonnes of coal. With deuterium abundantly available in seawater and new tritium breeding techniques in development (e.g. by the likes of Oxford Sigma), fusion promises safe, scalable, and virtually limitless power.

Compared to nuclear fission, fusion produces significantly less radioactive waste, with materials becoming safe in around 100 years — not thousands, and carries a much lower risk of catastrophic failure.

Once considered a far-off fantasy, fusion is now edging closer to reality. In 2025, the EU unveiled its Competitiveness Compass, a roadmap that includes a new fusion strategy and public-private partnerships. The ITER project in France continues to make progress, while the UK has committed £410 million to develop the STEP prototype fusion plant, expected to be operational in the 2040s.

Why intellectual property matters

As hydrogen and fusion technologies scale up, the role of intellectual property becomes more critical than ever. Both fields face substantial barriers: long R&D timelines, high capital costs, and complex global supply chains. In this environment, IP provides innovators with a strategic advantage — helping protect their ideas, attract investment and support market growth.

IP and access to funding

In the hydrogen sector, around half of international patent families in the period 2011-2020 related to hydrogen production technology, with most of the patents filed in 2020 shifting toward greener hydrogen production methods.

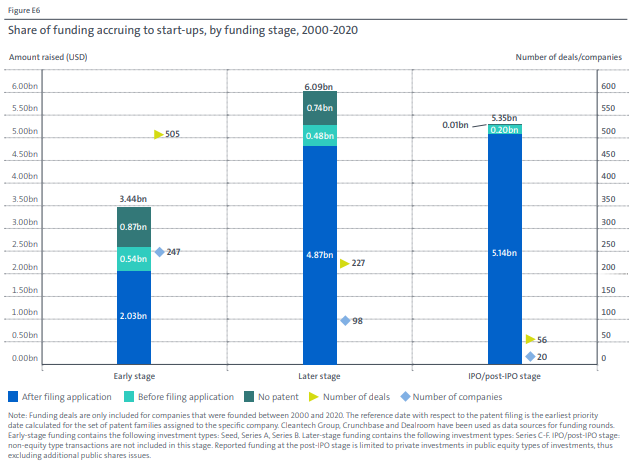

It has been found recently that over 80% of late-stage venture capital funding in the hydrogen sector has gone to companies with existing patent applications. (See above graph; source)

In comparison, in the fusion space, innovators have commonly eschewed the pursuit of patents, believing commercial fusion to be too far off for a 20-year patent term to be relevant. That logic is now shifting, particularly as US-based fusion firms with robust patent strategies dominate funding rounds.

IP and collaboration

IP does more than protect inventions — it creates the legal scaffolding that enables meaningful collaboration. In frontier technologies like hydrogen and fusion, where development costs are high and technical expertise is globally dispersed, innovation increasingly happens across borders and between sectors. Whether it’s a private company building on public R&D or international teams co-developing fusion reactors, clear and enforceable IP rights are essential to align incentives, manage shared risk and ensure fair returns. In this way, IP acts not as a barrier, but as a bridge — fostering the trust needed to turn bold ideas into shared progress.

IP and market confidence

In emerging clean energy sectors such as hydrogen and fusion, IP will serve as a key instrument of market confidence. Hydrogen and fusion technologies are often capital-intensive, complex, and years away from profitability. For investors, robust IP portfolios will provide assurance that a company’s innovations are both unique and defensible — that they are not merely speculative science projects, but investable propositions. Patents thus have a key role in transforming R&D into tangible, protectable assets, offering a degree of certainty in an otherwise uncertain innovation landscape. With greater certainty provided, IP in turn can help channel private capital into high-impact green technologies, accelerating their path from lab bench to power grid.

A tool for global impact

This World Environment Day, we find ourselves at a turning point. Hydrogen and fusion have the potential to reshape the global energy landscape — but realising that promise will require coordinated innovation, investment and policy support.

IP will play a central role. Not just as a tool for protection, but as a foundation for confidence, cooperation and commercialisation. To fully unlock its potential, we must also embrace IP models that support responsible licensing, open innovation and global access. If we succeed, IP may become one of our most powerful tools in the fight against climate change.

Managing IP has published its 2025 edition of the IP STARS legal directory. The directory acknowledges the most exceptional practitioners across a range of IP practice areas and more than 50 jurisdictions.

IP STARS is the leading specialist guide showcasing the legal practitioners best-equipped to handle contentious and non-contentious issues within intellectual property law. The research analysts determine the annual ranking using firm submissions, client interviews and online surveys.

We are delighted to announce that Partners Paul Cozens and Hazel Ford have been named as ‘Patent Stars.’ Out of our Trade Mark team, Partners Gary Johnston and Rebecca Tew have been recognised as ‘Trade Mark Stars.’ In addition, Consultant Partner Jane Clark and Partners Philippa Griffin, Nicholas Fox, David Hobson, Martin MacLean and Andrew White have been praised as ‘Notable Practitioners.’ Partner Laura Clews has also been newly featured as a ‘Notable Practitioner.’

The 2025 Rising Star rankings are due to be released in September 2025.

The firm is also pleased to have maintained its ranking ‘Trade mark prosecution’ in the 2025 directory. The firm rankings for ‘Patent prosecution’ will be announced at the end of the month.

For more information and to view the rankings in full, visit the IP STARS website here.