The European Patent Office (EPO) has issued updates for two cases being considered by the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBA); G 2/19 and G 1/18.

In the Autumn of 2017, the EPO’s Boards of Appeal moved from their location in central Munich to Haar, a suburb near to Munich but which is a separate municipality. In G 2/19, the EBA was, in essence, asked to decide whether holding oral proceedings in Haar was compliant with the EPC. The board has now said yes, it is compliant.

The decision in G 2/19 was good news for G 1/18, which was heard in Haar. This case relates to a point of law referred to the EBA by the President of the EPO, namely whether an appeal filed outside the two-month time limit of Article 108 EPC is to be deemed as ‘not filed’ or as ‘inadmissible’ – this determines whether or not the appeal fee (currently €2,255) can be reimbursed. The EBA has now issued an opinion that a failure to meet the two-month deadline of Article 108 EPC means that the appeal is deemed not to have been filed, and that an appeal fee paid under those circumstances should be reimbursed by the EPO.

For further information about these recent cases, or for any other general queries about EPO prosecution, opposition and appeal work, please get in touch with the Mathys & Squire team.

Amid changing technology trends, more rare earth metals are required to meet our needs – and patent protection may be one solution. In this article for Managing Intellectual Property, Mathys & Squire Partner Chris Hamer and Managing Associate Laura Clews, explain more.

Technology is a fundamental part of our everyday life, including how we communicate, travel, entertain ourselves and even how we power our gadgets, but very few of us ever question how sustainable our ever-increasing dependence on technology actually is.

What are rare earth metals?

Until recently, most people were unaware of the central role that rare earth metals play in modern day life. While this little group of metals may not be present in significant volumes within current technology, they are responsible for making technology smaller, lighter and more powerful than before. Rare earth metals are used in everything from optical fibres to mobile phones; catalytic converters to green technology; and are even responsible for providing the sharper and more vivid colours in our flat screen televisions and tablets. These metals have even been identified as essential for modern day defence applications, for example in guidance systems, lasers, and radar and sonar systems.

Given our increasing dependence on technology, our desire to own the latest gadgets and ever-expanding research into green technology, how can we ensure that there is a sufficient supply (both actual and economic) of these rare earth metals to meet our needs?

Fortunately, rare earth metals, such as cerium (Ce), dysprosium (Dy), lanthanum (La), neodymium (Nd), scandium (Sc), terbium (Tb), thulium (Tm), ytterbium (Yb) and yttrium (Y), are not as rare per se as the name suggests; in fact, they are relatively abundant in nature. The main barrier to supplying these metals is that they are only found in low concentrations in remote parts of the world and are hazardous and costly to mine and process.

One important area of developing technology is renewable energy. At the 2015 Paris Climate Conference, it was agreed to increase efforts to limit climate change, including increasing the use of electric vehicles. Several countries have set ambitious sales and/or stock targets regarding vehicle electrification as guidance for creating national roadmaps and for gathering support from policymakers. Among various uptake scenarios, the International Energy Agency and the Electric Vehicles Initiative, a multi-government policy forum, presented an aggregated global deployment target of 7.2 million in annual sales of electric vehicles and 24 million in vehicles stock by 2020.

Most electric vehicles (with the exception of Teslas) use neodymium iron boron permanent magnets (NdFeB), which are essential for the production of high-performance electric motors. Such magnets contain neodymium (Nd), praseodymium (Pr), and dysprosium (Dy) rare earth elements.

Based on current technology, a permanent magnet synchronous-traction motor for an electric vehicle needs between 1 and 2 kg NdFeB (Neodymium Iron Boron) depending on the motor power, car size, model, etc. Therefore, based on the current technology, to meet the global deployment target of 7.2 million electric vehicle sales in 2020, between 7,200 and 14,400 tonnes of NdFeB magnets would need to be manufactured. This would inevitably require a significant increase in the annual demand for NdFeB magnets in electric vehicles by up to 14 times in just five years.

In addition, many wind turbines also rely on NdFeB magnets to function. In 2015, the global demand in rare earth metals for permanent magnets for use in wind turbines was around 2,500 tonnes. Due to the increasing demand for renewable energy, this value has been predicted to increase to 7,000 tonnes in 2020.

The two examples presented above simply highlight the dramatic increase in demand for rare earth metals in the coming years and does not even take into consideration the reported 1.5 billion smartphones sold in 2017 or the estimated 16 million smartwatches sold by Apple in 2017.

While global resources of rare earth metals have been estimated at around 110 million tonnes, the global supply of these metals is limited due to the cost, complexity and environmentally hazardous process of extracting and separating them, as well as the producers themselves.

At present, China accounts for around 90 to 95% of the global market for rare earth metals. As the environmental regulations in China are not as strict as those in Europe or the US, it has been possible for China to produce these metals at a much lower cost compared to other countries and, therefore, out-compete mines like Mountain Pass in the US. However, recent global economic issues mean there is significant risk in there only being a single large supplier.

Profile 1: Seren Technologies

One UK company tackling this issue head on is Seren Technologies. This business has developed a revolutionary extraction method for recycling rare earth methods using ionic liquids. An ionic liquid is a salt in which the ions are poorly coordinated, resulting in these solvents being liquid below 100°C, or even at room temperature. One benefit of using ionic liquids in recycling methods is that they have lower levels of volatility and flammability compared to the organic solvents (such as those used in previously-known recycling methods), providing a safer and more environmentally-friendly method. In fact, this new recycling process has been reported to have an environmental footprint that is one hundred times smaller than other known recycling methods.

Seren Technologies’ research is based on the use of hydrophobic ionic liquids comprising a nitrogen donor and additional electron donating groups which act as a molecular recognition ligand to improve the selectivity and levels of recovery of rare earth metals. It has been reported that this new patented process (WO 2018/109483) can separate mixtures of dysprosium and neodymium with a selectivity of over 1000:1 in a single processing step, meaning that this research can not only lead to increased levels of recycled rare earth metals but that this can be achieved in a less time-consuming, more cost-efficient and a more environmentally-friendly way.

Seren Technologies opened its pre-commercial permanent magnet recycling plant at the Wilton Centre in the north of England on December 3 2018, illustrating 98% selectivity of rare earth metals in a single separation step, taking only two hours, marking a significant reduction in the time required to select these rare earth metals.

With the aim to bring this technology to market on an industrial scale, it could represent a significant leap forward in the viability of recycling rare earth metals in a safer and more economically-viable way.

Extraction and purification

The process of extracting and purifying rare earth metals typically requires the following steps:

- extraction of a rare earth metal-containing material – for example mining an ore containing rare earth metals;

- increasing the concentration of the rare earth material;

- purifying the rare earth metal containing material – this is most commonly achieved through solvent extraction (the process of partially removing a substance from one solution by dissolving it in another, immiscible solvent in which it is more soluble), wherein the separated metals are in the form of carbonates, oxalates or hydroxides. However, due to the similar physical and chemical properties of rare earth metals, it can be difficult to separate these mixtures into individual components, so producing a full separation of rare earth metal may require hundreds of process steps; and

- refining the extracted rare earth metals – using complex processing including converting separated rare earth compounds to metals using molten salt electrolysis and metallothermic reduction methods; such methods require large electrical inputs.

Previously, recycling methods for rare earth materials have often been based on a multiple-stage solvent extraction, such as the one discussed above, requiring large amounts of chemicals and energy input. While several alternative methods have been proposed over the years, very few have been scaled up and tested at the required production volumes.

Profile 2: Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Across the pond, the US government has been funding research into methods of effectively recycling rare earth metals. One project, by the Worcester Polytechnic Institute, has focussed on extracting rare earth metals from machinery without the requirement of first dismantling the machine to be recycled. Typically, rare earth materials are contained within the inner most parts of the machine and are, therefore, not readily accessible. Accordingly, previously known methods have required substantial time and cost in order to access the relevant machinery part for recycling.

In response to these issues, Worcester Polytechnic Institute has produced a low-temperature method of extracting rare earth metals from fragmented end-of-life machinery. The patented method (US 2016/208364) requires the steps of first demagnetisation of the metal through heating, for example, the end-of-life machinery can be heated in a furnace at a temperature of at least 400°C for 60 minutes in order to demagnetise metals contained therein. The material is then shredded to break the present magnets. Finally, the rare earth metals are extracted through the use of a leaching solution via hydrochloric acid to produce a solution of the dissolved magnet material, followed by precipitating the rare earth metals using oxalic acid.

It has been reported that the method provides recovery efficiencies of up to 82% with rare earth metals having a purity of over 99%.

Rare earth metals and politics

The vast majority of the global market for rare earth metals is dependent on the production in China. However, does this considerable reliance on one source of rare earth metals make technology, renewable energy and defence markets vulnerable?

In 2010, China announced that the amount of rare earth metals to be exported would be reduced due to domestic requirements and concerns over the environmental effects of mining. The amount of rare earth metals exported from China was dramatically reduced from 50,145 tonnes in 2009 to 31,130 tonnes in 2012, causing a sharp increase in the cost of exported rare earth metals. In 2012, Japan, the US and the EU complained to the World Trade Organization (WTO) about these restrictions. Although China cited environmental reasons for the reduction of export quotas, the WTO ruled on 26 March 2014 that China’s export limits violated the WTO rules. However, the amount of rare earth metal ores mined in China in 2016-2017 only amounted to around 105,000 tonnes.

Therefore, the current supply of rare earth metals is failing to meet the ever-increasing demand in the modern world.

To add further concerns, it would seem that politics can also play a significant role in the supply of rare earth metals from China and, therefore, the possibility of manufacturing technology and defence applications.

In 2010, China reportedly blocked exports of rare earth metals to Japan for a period of time following a dispute regarding the detention of a Chinese fishing trawler captain, however the dispute between these two countries was ultimately resolved and exportation of the metals resumed.

Worryingly, it seems that history may be repeating itself following a statement made in May by US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer regarding a proposition to increase tariffs on imports from China:

“Earlier today, at the direction of the president, the United States increased the level of tariffs from 10% to 25% on approximately $200 billion worth of Chinese imports. The president also ordered us to begin the process of raising tariffs on essentially all remaining imports from China, which are valued at approximately $300 billion.”

Clearly, China does not consider the enforcement of these new US tariffs to be reasonable and there is concern that China may use its considerable dominance in the supply of rare earth metals as leverage in this trade dispute. Reporting comments by Wang Shouwen, a vice commerce minister for China, the newspaper News of the Communist Party of China said that:

“Even after China overcame difficulties to find pragmatic solutions to many issues raised by the US, it still wanted a yard after China offered an inch,” said Wang, who is part of the Chinese negotiating team, noting that the US insisted on ‘unreasonable’ demands, including terms that violate China’s sovereignty.”

In view of this ongoing dispute, there is growing concern that China will consider restricting the export of rare earth metals to the US in retaliation if the tariff increase on the importation of Chinese goods is not lifted (not surprisingly, rare earth metals were excluded from US tariff increases).

Profile 3: Iowa State University Research Foundation

Further research funded by the US government includes the work by the Iowa State University Research Foundation (US 2018/312941). The disclosed method recycles rare earth metal-containing materials from end-of-life products such as permanent magnets from computer hard disk drives, electric motors and batteries. The patented process comprises the steps of contacting the rare earth metal-containing material with an aqueous solution of a copper (II) salt to dissolve the material in the solution. The dissolved rare earth metal is then precipitated from the aqueous solution as rare earth metal oxalate, sulphate or phosphate. The precipitate is then calcined to produce a rare earth metal oxide.

It has been reported that the above method can provide over 99% purity of the rare earth metals in the form of oxides, sulphates or phosphates.

Recycling rare earth metals

As fears grow that the availability of rare earth metals may soon be restricted, many companies outside of China are looking at ways to limit their dependency on China for the supply of rare earth metals, and are now turning to possible alternative components or funding research into methods of recycling these precious metals. The ability to provide an environmentally-friendly, cost-effective method of recycling rare earth metals providing higher levels of purity and selectivity could meet a significant percentage of the demand in, for example, EU countries, the US and Japan, but does such a process exist?

While recycling rare earth metals (often referred to as ‘urban mining’) would be a fitting solution to the current crisis, previously used methods of recycling rare earth metals still require the use of toxic/hazardous chemicals; a large number of processing steps (therefore requiring high process times, which increase the costs of the recovered metals); and have poor selectivity, meaning that lower amounts of rare earth metals are actually recovered from the recycling process. All of these issues are leaving many countries wondering how they can possibly keep up with the growing demand for these versatile metals.

Fortunately, many companies have undertaken significant research to resolve these problems. Given that the global rare earth metal market was reported to be worth $8.10 billion in 2018 and has been estimated to be worth $14.43 billion by 2025, the companies researching cost-effective and highly selective recycling methods are, of course, carefully protecting these innovative methods from third party use. For example, obtaining patent protection, with particular emphasis on protecting these methods in many of the countries in which such a recycling process may be performed, plays a significant role in the essential IP protection (see profiles 1, 2 and 3).

As some companies, such as Seren Technologies (see profile 1), seem to be close to making their recycling methods available to the public, it would seem a real possibility that the amount of rare earth metal that can be efficiently recycled can be significantly increased in the near future, thereby reducing our dependence on external providers. However, whether this can be achieved before the cost of these metals increases as an effect of ever-growing demand or further political turmoil remains to be seen.

For more information about patent protection, please visit our patents page.

This article was first published by Managing Intellectual Property – available here (login required).

This Saturday, 20 July 2019, marks 50 years since Neil Armstrong first stepped on the moon, and inspired millions around the world to enter careers in science and engineering.

In the intervening years, we have seen a shift in innovation in the space sector from previously state-owned activities to now private and commercial activities, operated by the likes of SpaceX, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic. As a consequence, the protection of intellectual property in the space sector is rapidly increasing.

Blue Origin LLC, for example, have a number of patents granted to innovations ranging from multiple stage rocket systems and new composite structures for aerospace vehicles, to methods for compensating for wind prior to engaging airborne propulsion devices for enabling reusable launch vehicles to land.

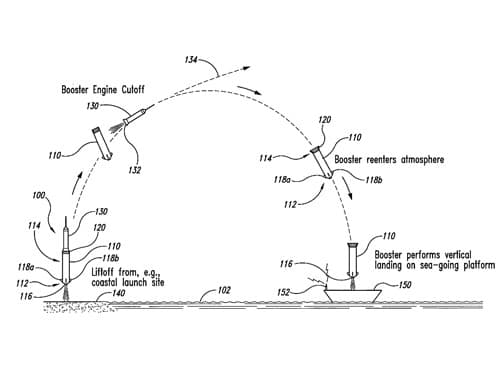

Figure 1 U.S. Patent 8678321, “Sea landing of space launch vehicles and associated systems and methods”

Why protect innovations that are going to be used in space?

Because intellectual property (IP) rights are territorial rights, at first sight, the thought of protecting inventions that are going to be used in space may seem counter-intuitive.

However, the US Patent Act (35 U.S.C.§ 105) states that any invention made, used or sold in outer space onboard a spacecraft that is under the jurisdiction or control of the USA is considered to be made, used or sold on US territory. Therefore US patents may indeed cover activities in outer space.

While many other countries don’t have similar provisions written into law, there are reasons those active in the space sector should look to cover territories other than just the US. For example, before a satellite or innovation is actually in space, it is typically designed and made somewhere on Earth. Patent rights can therefore cover those activities that take place on Earth.

However, careful thought needs to be given as to how such patents are drafted and where they are filed – what activities are you specifically looking to cover? If the patent is to be directed to a physical object – e.g. a rocket or engine – then obtaining protection in territories where the object is designed, made and likely to be launched from (both by you and a competitor) seems prudent. But what if the patent is to be directed towards a new method – such as a new way a satellite may communicate with objects on Earth? In such cases the patent claims need to be carefully drafted to capture only the activities that are performed on Earth within their scope – otherwise there may be a case of “divided infringement” where the patent is never actually infringed because not all steps of the claimed method are performed in the territory which the patent covers.

The space sector in the UK is growing fast

A recent report from the House of Commons Committee on Exiting the European Union noted that the UK space sector has trebled in size in real terms since 2000 and captures between 6.3 and 7.7 % of the global market, with a turnover in 2014/15 of £13.7 billion. This figure looks set to grow.

The UK is a world leader in the development of small- and micro-satellites, and the UK Government has committed to enabling low-cost space launch from the UK by 2021, with the view to developing commercial spaceports in the UK. The protection of the intellectual property in such small- and microsatellites is as important as it is for intellectual property in any sector. If such small- and microsatellites are to be launched in the UK, then patents covering the UK will cover the making, importing or use of any such satellites in the UK, which is particularly relevant if they are to be launched from the UK.

There are therefore good reasons why those active in the space sector should consider obtaining patent protection as part of a wider overall IP strategy that acts to help preserve their R&D investment and helps them to achieve their long-term commercial goals.

The team here at Mathys & Squire has specialist expertise in protecting IP in the aerospace sector and already work with a number of businesses active in this thriving industry. If you are looking to protect the innovations in your business, please get in touch with us today.

The extended version of this article has been published by Managing Intellectual Property – available here (login required).

We are delighted to share the new Mathys & Squire logo and brand.

Since Mathys & Squire was founded in 1910, the firm has grown and changed shape in many ways. From the move of our London office in 2014 from Holborn to the iconic The Shard, the acquisition of Coller IP in 2018, various new offices opening around the UK, to a brand-new office in Munich on 1 July 2019. We thought it was time to reflect our modern, innovative approach by refreshing and modernising our brand.

An important challenge in refreshing our logo was to meet the requirements of today’s ever-changing world; after over a century in the marketplace, Mathys & Squire’s new logo now represents a full-service firm with well-established IP specialists, leading the field with insight, innovation and quality.

Our constant strive for excellence is instilled in everyone who works in the firm and our unrelenting focus on delivering the best client service in the industry is what keeps pushing us forward.

To find out more about Mathys & Squire, click here.

Before:

After:

Mathys & Squire has featured in the Financial Times’ report of ‘Europe’s Leading Patent Law Firms 2019‘.

2,727 clients and peers participated in the survey, with several thousand recommendations being made to recognise Europe’s leading firms for patent prosecution and patent strategy consultation services.

Patent law firms could be recommended both in general and for specific categories that covered a range of specialist services. Mathys & Squire is delighted to announce that it has been recommended in the following sectors:

A full copy of the report can be accessed via the Financial Times website – here.

In this article for Managing Intellectual Property, Mathys & Squire Associate Alex Robinson provides expert commentary on whether the revised rules of procedure at the EPO’s Boards of Appeal are likely to improve efficiency.

Revised rules of procedure at the EPO’s Boards of Appeal and their focus on avoiding late amendments and submissions could see parties ‘front-load’ their arguments at an earlier stage, causing a headache for first instance divisions, lawyers say.

The revised rules were adopted after the latest meeting of the EPO’s oversight body, the Administrative Council (AC), at the end of June.

Among the changes are stricter measures for dealing with submissions made during an appeal and a tweaking of the rules on when cases can be remitted back to the decision of first instance.

The revised rules, intended to combat the EPO’s backlog, will come into force in January next year. Alex Robinson, patent attorney at Mathys & Squire in London, says the tightening up of amendments at the appeal stage could result in a “precautionary front-loading” of requests, amendments and supporting evidence into first instance proceedings.

Article 12 of the revised rules clarifies that any amendment to a party’s appeal case after it has filed its initial grounds of appeal will be “subject to the party’s justification and may be admitted only at the discretion of the board.”

Robinson says parties may take a precautionary approach in light of this and try to account for “every possible permutation of issues in documents filed in first instance proceedings.”

This, he says, would allow parties to keep the opportunity to address every possible point should the need arise during a subsequent appeal. He notes, however, that this could increase the workload of the first instance divisions.

Robinson says the boards were already quite strict on this, but that “by putting it into the black letter of the rules,” the EPO has taken away some of the discretion that the boards theoretically have under the current rules.

The new rules will not apply to cases where the grounds of appeal are filed before the start of 2020, or where a summons to oral proceedings has already been issued by then.

Robinson says this may prompt “a flurry of activity” in the next six months as attorneys whose cases would otherwise be subject to the new rules try and get in as many arguments and amendments as they can now, so as not to fall foul of any stringency in the revised rules.

Patent ping pong

A major reason behind the rule changes – approved during the AC meeting of June 26 to 27 – is to avoid first instance decisions being appealed and patents then entering a ‘ping-pong scenario’ between the first instance and appeal stages, adding to the office’s overall backlog.

Article 11 of the revised rules now says the board shall not remit a case unless ‘special reasons present themselves for doing so’.

Previously this part of the rules stated that the board shall remit a case to the department of first instance if fundamental deficiencies are apparent in the first instance proceedings, ‘unless special reasons present themselves for doing otherwise’.

Robinson notes that if a patentee appeals against a first instance decision, the boards will quite often send a case back, but that the new rules clarify that this will only happen if special procedural reasons are highlighted.

Robinson says: “The backlog is notorious and it’s a laudable objective to try and combat this. But some of the rules could be seen as using a sledgehammer to crack a nut.”

The EPO’s backlog is regularly bemoaned. However, critics have previously told Managing IP that the office’s latest strategic plan shows there is too much focus on trying to grant patents quickly rather than ensuring they are of sufficient quality.

The revised rules, although positive in limiting the scope for reassessment, could muddle things further by overloading first instance divisions with claims that may not be relevant at the time.

This article was first published in Managing Intellectual Property – click here to read the full piece via their website (login required).

All roads lead to Rome, all Silk Roads lead to China. With the latest, most ambitious Chinese initiative dawning upon us, it is essential for IP right holders to factor in the changes and challenges that come along with the One Belt One Road (OBOR) strategy.

What is the OBOR?

The OBOR is a Chinese strategy which was initiated in 2013. Its aim is to forge closer economic ties by linking Europe and Asia through an improved transport infrastructure, consisting mainly of new rail routes, called ‘belts’, and new maritime routes, confusingly called ‘roads’.

The strategy has gained popularity rapidly, with over 80 countries adhering to the overall initiative since 2013.

The threat

One of the ‘belts’ connects China with Europe, with trains arriving in Paris and London and one of the main ‘roads’ will start in China and reach Italy through the Suez Canal, connecting with ports in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Seychelles and Africa on the way.

We are, therefore, witnessing the development of a fast transport system that joins together new production countries in Southeast Asia, Central Asia and Africa, with western countries of destination. Add in the lower costs of production, the increasing number of free-trade zones and the less stringent customs controls along the OBOR routes and you’ve got yourself a very favourable environment for counterfeiting and organised crime activities.

The maritime routes will remain cheaper and thus preferred by counterfeiters in some instances, while the new railways provide for much faster transport, which could serve as a more appropriate method of ferrying a wide range of ‘limited life’ goods, such as pharmaceuticals and foodstuffs.

UK, EU and the OBOR

The European Commission has stated that the EU will be the final destination for at least one-third of Chinese exports, with an estimated value in excess of $600 billion per year. By 2020, it is suggested that this could reach $1 trillion.

With the UK set to leave the EU, right holders are concerned that due to a potential bilateral trade deal with China, the UK will become the destination for huge volumes of counterfeit goods, but that the UK will not deploy the corresponding levels of additional customs control. Moreover, there are concerns that post-Brexit, the cooperation between EU and UK customs could suffer, with the EU limiting access to its information and intelligence.

The solution?

In light of all this, both EU and UK right holders call for long term, policy preparation for the development of the OBOR strategy. They urge the West to take the initiative and improve the customs control capacity at ports, free zones and rail stops, and lobby for better control and expertise in the Southeast Asian, Central Asian and Eastern European countries.

As for the relations between the UK and the EU, right holders believe it vital that the two parties take joint responsibility and work together to ensure safety and security, even after Brexit concludes. This will certainly be a work in progress and we will be sure to keep you updated as things progress.

IP rights are valuable business assets and can be an important source of financing.

Virtually everything your business creates, that sets it apart from your competitors, is likely to attract some form of intellectual property (IP). It is, therefore, important to understand the significance of IP to your business and how you go about protecting it.

Registered rights such as patents, trade marks and Registered Designs are reasonably widely familiar, but many businesses are unaware of their less tangible, unregistered IP rights, that exist automatically when something is created, and require no registration procedure. These could, in fact, be hugely valuable assets in their own right. Examples include copyright, unregistered design rights, database rights, semiconductor topography rights, know-how, confidential information and trade secrets. It is well known, for example, that the Coca Cola recipe is one of the most valuable trade secrets in the world, and continues to set them apart from their competitors.

Here are some top tips on how to protect your business’ IP:

Identify what IP your business has (or could have)

IP cannot add value or help to grow your business if you don’t know it’s there. It doesn’t just help to protect the things that make your business unique, but can also help you to raise crucial funds in order to grow your business.

Understand the unregistered IP rights that already exist within your business

It is rare for a business to have no IP at all, so even if you don’t have any registrable IP, you may have unregistered rights which can be just as valuable.

Know when to keep your ideas confidential and when it is safe to share them

Whether it’s a trade secret or a patentable invention, confidentiality can be a crucial part of your IP strategy.

Identify registrable IP to best protect the key USPs of your business

Strategic use of registered IP, such as patents, designs and trade marks, can protect your USPs to give you the competitive advantage to grow your business or attract investment.

Create an IP strategy to help secure funding

Whether you need to borrow against the value of your IP, secure grant funding or attract investment, the right IP strategy can help, whereas a weak or non-existent IP strategy can be detrimental.

Understand the financing options available to you

Investment (whether private equity, angel, grant-based or even crowdfunding) is not the only way to finance your business for growth. Sometimes, a more attractive, and potentially quicker, option is to simply borrow the money you need to implement your growth strategy.

There are a number of ways for a small business to borrow money to fund their growth, such as these peer-to-peer websites: Funding Circle, RateSetter and Zopa.

However, not all businesses are sufficiently ‘creditworthy’ to consider what is essentially an unsecured loan, and this is where your IP could really help. IP rights are not only valuable business assets, but they can also be an important source of financing, because an ever-increasing number of lending institutions are extending their businesses to provide loans on the basis of IP, and some banks use IP assets as a credit enhancer, so knowledge and understanding of all of your IP rights could be crucial.

The management and protection of your IP should be seen as an ongoing discipline that is aligned with, and an integral part of, your business planning and strategy. Unless assets are protected, why would a third party invest if there is nothing to stop rivals from copying ideas and innovation?

This article was first published in Business Game Changer magazine in July 2019.

You’ve had a great idea for a new product, so what do you do next?

In this article for Business & Innovation Magazine, we provide some top tips on raising funding in order to develop your business.

Some degree of product design is likely to be needed and you would expect the result of that, in the first instance, to be a minimum viable product (MVP) or working prototype that can be tested and ‘tweaked’ before the design is finalised for manufacture. This is, of course, a very simple description of what can often be a rather lengthy and complex journey which doesn’t end there, and, somehow, needs to be funded until sales revenue starts to cover the overheads.

In general, a new or growing business may (potentially) go through several rounds of funding to raise capital as it progresses along the road from concept to market, and these funding rounds can be broken into three broad categories, namely:

- Pre-seed

- Seed

- Series A (and even B, C, D, etc.)

Raising capital can, in itself, be an arduous and frustrating process, but pre-seed funding, in particular, can be exceptionally difficult, because this is the capital you need for early-stage product development of an MVP, testing and finalising the product design. Not only that, you may need to pay for intellectual property registrations, market research, branding, etc. out of this capital, and yet you may not yet have anything viable for potential investors to buy into, nor anything tangible to borrow against.

There are a number of different ways to raise pre-seed funding, and although they are not all covered here, broadly speaking, many startup and scale-up ventures raise their pre-seed capital by one (or a combination) of:

- crowdfunding;

- grant funding;

- private (angel or personal)

- investment; and

- R&D tax credits.

With the exception of R&D tax credits, all successful bids for investment/funding are likely to have one thing in common: getting the message right.

So how do you go about getting your message across and attracting the right investors?

It is rarely possible to effectively do everything that needs to be done yourself, and it is crucial to have an effective core team and good relationships with at least a couple of credible service providers, such as an intellectual property attorney, product designer, branding specialist and marketing expert. It is this network of people that you want an investor to recognise as credible and sufficiently effective to take the business to the next stage.

Su Copeland of Priddey Marketing explains: “It isn’t easy to find the right investors, and doing so requires knowing where to find them and then having an attractive pitch.”

There is no doubt that the start-up journey is long and often complex. It almost always takes longer and costs more than you probably expected, but with the right people around you, and the right advice at the right time, you are much more likely to succeed in the end. Su has provided her top 10 tips below.

Top 10 tips for attracting investors

|

Das hochrangige Unternehmen für geistiges Eigentum, Mathys & Squire LLP, treibt seine Expansion in Europa voran. So hat es heute die strategische Ergänzung eines äußerst respektierten Münchner IP-Teams verkündet, das unter der Leitung von Dr. Gerold Fiesser steht. Nachdem erst kürzlich neue Büros im Vereinigten Königreich eröffnet wurden, verfügt das Unternehmen nun über zehn Standorte im Vereinigten Königreich sowie auf Kontinentaleuropa, einschließlich in Paris, Luxemburg und München.

Dr. Gerold Fiesser, einer der führenden Patentanwälte Deutschlands, schließt sich Mathys & Squire in München mit seinen Kunden und einem Team des deutschen IP-Unternehmens Herzog Fiesser & Partner Patentanwälte, das er 2010 mitbegründete, an.

Begleitet wird er dabei von Dr. Giuditta Biagini, Dr. Lorraine Aleandri-Hachgenei und Dr. Kirstin Wenck sowie von angehenden AnwältInnen und einem Supportpersonal. Zudem wird dem neuen Team zusätzlich technische Unterstützung aller anderen Mathys & Squire-Büros zugutekommen.

Dr. Fiesser ist ein deutscher und europäischer Patentanwalt sowie Anwalt für Markenrecht und Designschutz. Er ist in allen Gebieten des Patent- und Markenrechts tätig, wobei seine Schwerpunkte auf der Einreichung und Weiterverfolgung von Patentanmeldungen, Einspruchs- und Beschwerdeverfahren sowie Patentstreitigkeiten liegen, die sich auf Konsumgüter, Life-Sciences und die Sektoren der organischen Chemie und Polymerchemie, einschließlich persönliche Pflegeartikel und ihre Zusammensetzungen, Schönheitsprodukte, Anwendungen von Polymerchemie und Polymeren sowie Zusatzstoffe, Öle und Fette, beziehen.

Als qualifizierte italienische und europäische Patentanwältin spezialisiert sich Dr. Giuditta Biagini auf die Vorbereitung von Gutachten zur Ausübungsfreiheit und Validität, Patentanmeldeverfahren sowie Einspruchs- und Beschwerdeverfahren im Bereich der Chemie, pharmazeutischen Chemie und der Polymere.

Dr. Lorraine Aleandri-Hachgenei ist eine deutsche und europäische Patentanwältin, Anwältin für Markenrecht und Designschutz sowie US-amerikanische Patentvertreterin. Ihre Fachgebiete umfassen Einsprüche, Beschwerden, Gutachten zur Ausübungsfreiheit, Rechtsstreitigkeiten und Due Diligence. Aleandri-Hachgeneis Tätigkeit fokussiert sich auf Chemie, Physik und Ingenieurwesen, einschließlich medizinische Produkte und pharmazeutische Verabreichungsprodukte.

Dr. Kirstin Wenck ist eine deutsche und europäische Patentanwältin sowie Anwältin für Markenrecht und Designschutz. Ihre Tätigkeitsschwerpunkte umfassen die Betreuung von Patenterteilungs- und Einspruchsverfahren sowie Markenerteilungs- und Einspruchsverfahren auf dem Gebiet der organischen Chemie und der Polymer- und Biochemie.

Über den Zusammenschluss mit dem neuen Mathys & Squire-Büro sagte Dr. Gerold Fiesser: „Mein Team und ich freuen uns, Teil eines solch renommierten und hochrangigen Unternehmens zu werden. Einer der Schlüsselfaktoren für den Zusammenschluss war das positive Ethos, das wir teilen, sowie die aufrichtige Begeisterung zusammenzuarbeiten, um all unsere Kunden auf höchstem Niveau zufriedenzustellen.“

Fiesser meinte weiter: „Mathys & Squires Größe, internationale Reichweite und großer Support im Vereinigten Königreich, in den USA und in Asien werden für unsere Kunden in wichtigen internationalen IP-Jurisdiktionen von großem Vorteil sein. Zudem können wir dem internationalen Kundenstamm von Mathys & Squire, wie auch seinem Kundenstamm aus dem Vereinigten Königreich, durch unsere weitreichende Erfahrung und geografische Nähe zum Europäischen Patentamt, zum Deutschen Patent- und Markenamt sowie zum Deutschen Bundespatentgericht bestmöglich dienen.“

Dr. Paul Cozens, Seniorpartner von Mathys & Squire, meinte: „Wir sind wirklich hocherfreut, dass sich Gerold und sein Team dem Unternehmen in München anschließen. Uns war es wichtig, nicht nur ein bewährtes Team, das sich der Ausübung höchst qualitativer Arbeit widmet, sondern auch Menschen zu finden, die sich gut in unsere inklusive und freundliche Kultur eingliedern und mit uns und unseren Kunden weiterwachsen. Wir genießen seit einiger Zeit eine große Präsenz in Europa und das Büro in München wird perfekt mit unseren Teams im Vereinigten Königreich und in Paris und Luxemburg harmonieren. Nach dem Brexit ist eine anerkannte Expertise innerhalb der EU von absoluter Wichtigkeit, um unsere internationalen Kunden zufriedenzustellen.“