The UK Government, via the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), recently announced a call for views on new proposals to improve and strengthen UK clinical trial legislation.

In brief, the consultation is designed to seek opinions on proposals to update clinical trial legislation with a view to increasing patient and public involvement, improving diversity of trial participants, streamlining approvals and enhancing transparency.

The responses will help the UK Government assess whether changes to the legislation can help make the UK a hotspot for the research and development of new healthcare products, with the aim of promoting innovation whilst protecting patients and trial participants.

Why is this consultation happening?

The Medicines and Medical Devices Act 2021 provides the powers to update the legislation for clinical trials. Since the UK left the European Union in 2020, the Government is seeking to position the UK as a go-to sovereign regulatory environment for clinical trials. The Government also intends to support the development of innovative medicines and ensure that the UK retains and grows its reputation as world leading life sciences base, generating opportunities for skilled jobs.

This consultation supports a wider programme of work in relation to developing and optimising the UK’s clinical research environment as part of the UK Government’s Saving and Improving Lives: The Future of UK Clinical Research Delivery and its implementation initiative, as well as its Life Sciences Vision.

What will the consultation focus on?

The call for views focuses on a number of specific areas:

- Patient and public involvement – in particular, how to focus trials on patients to achieve the best outcomes, and to address barriers to participation to make trials as inclusive as possible.

- Research transparency – to make sure that trial findings benefit the research community, participants, health professionals and other stakeholders.

- Clinical trial approval process – streamlining processes to support quicker timelines for approval and provide a competitive advantage when running trials in the UK.

- Research ethics – to safeguard the rights, safety, dignity and well-being of people taking part in clinical trials.

- Simplifying obtaining informed consent in cluster trials to encourage update in lower risk trials.

- Safety reporting – balancing high standards of participant safety whilst removing reporting requirements that burden investigators without improving safety.

- Good clinical practice – updating principles to ensure flexibility and applicability across a range of trial types.

- Appropriate sanctions – to ensure proportionate and strong regulatory oversight.

- Manufacturing and assembly – in particular, labelling requirements for auxiliary medicinal products and for authorised products to allow for risk-adapted labelling.

Responding to the consultation

The call for views will run until 11pm on 14 March 2022 – respondents must submit a completed response form (available online). The form sets out a number of questions further breaking down the key areas described above.

What happens after 14 March 2022?

After the deadline, the UK Government will consider the responses and we can expect the publication of a formal report summary in due course. The call for views states that the information obtained will inform the Government’s decision on any potential changes to the clinical trials legislation and to support the clinical research ecosystem.

We are pleased to see the attention the UK Government is dedicating to promoting innovation and creativity within the UK using IP frameworks. If any clients or contacts have views on any of the questions the consultation seeks answers on, we would be happy to hear their thoughts.

In this article for The Patent Lawyer Magazine, Partner Andreas Wietzke discusses Blackberry’s announcement on selling its non-core patent portfolio to Catapult IP Innovations Inc. and discusses the implications of this decision.

Earlier this month, software company Blackberry announced it was selling its non-core (those relating to mobile devices and wireless networking) patent portfolio to Catapult IP Innovations Inc. for $600 million. While the patents included in the portfolio don’t relate to Blackberry’s current core business, they operate in the mobile communications sector, which is likely the most litigation-intensive technology area in the patent system in the last few years. It can therefore be assumed that there will be a corresponding increase in exploitation through licensing efforts and related patent infringement proceedings.

As in previous years, extensive patent pools of mobile phone companies in particular offer investment opportunities for large fund companies. This allows companies to generate returns from their research & development (R&D) investments even after the products in question are no longer available on the market or a product area is completely abandoned, as in the case for Blackberry. However, this form of exploitation is not without controversy.

Potential users of patents sold and exploited in this way are particularly critical of the fact that they now see themselves exposed to a change in risk and a potential increased likelihood of legal action. While in a patent dispute between competitors there are usually extensive negotiation options due to mutual dependencies, pure patent investors have an exclusive interest in the economic exploitation of the acquired property rights through licensing income. Although this may significantly reduce the negotiation options in an infringement dispute, it does not fundamentally contradict the core idea of the patent system. Rather, an IP right exploited in this way is also based on an R&D investment originally made by a company and a developed technological innovation. As a result of its innovative strength, at least part of the exploitation success also flows back to this company in the form of the sales price of its patents.

While this development could be viewed critically by potential users of the protected technology, such investments can also be seen as a further strengthening of the patent system. From the point of view of a selling company, investments in development and innovation can contribute economically even if market success is not achievable in other areas, such as manufacturing effort, market share, marketing effort, etc. In other words, by adopting a proactive protection strategy at an early stage of development work, a company can create economic security for its investments. In fact, one of the original purposes of the patent system was to provide such protection for research investments. For this economic protection, it is now possible to make use of the ‘exploitation service’ of the investment companies, so to speak, without having to take legal action of one’s own.

The general concept of patent protection is based on an exchange between the state and the company. In return for publishing a technical solution as part of the patent application, the company receives a time-limited monopoly for commercial exploitation. Access to this monopoly is limited by the grant requirements, and automatic publication serves to accelerate technical development by spurring other companies to develop better solutions. The use of sold patents by patent exploiters does not change this core concept. Rather, it similarly encourages all market participants to actively invest in innovation themselves, thereby advancing the technology.

It can even be argued that the possibility of selling a patent to an investor means that other companies must in principle take its protective effect more seriously than before, since soft factors – such as mutual dependencies or a strong imbalance in the economic power of the two parties – no longer play a role as a result of the possibility of sale. With this view, the development of the exploitation opportunity through asset deals (such as the recent Blackberry example) can also be considered a positive addition to the patent system, as it secures the investments of companies to a further extent.

Following the preceding argument, the fact that company patents are considered as independent assets actually strengthens the value of the patent system and the individual property rights. This applies in particular to small and medium-sized enterprises, which have so far been exposed to a vast imbalance of power as patent owners against large corporations in patent disputes. If the current high volume patent sales, which receive much media attention, are still in the majority, this concept also seems to be transferable to smaller scopes without causing significant issues. Purchases of small patent bundles, individual patents or even the pure investment in an infringement dispute, are also conceivable.

One could therefore summarise that for innovation-driven companies, particularly startups and scaleups, the current development can be viewed positively. However, to the same extent, especially in large companies, an adjustment of the risk assessment for potential infringements of third-party intellectual property rights may be necessary, which includes the possibility of exploitation by sale. The trend towards more active use of the patent system, however, does not seem to contradict the basic idea of increasing the strength of innovation and the speed of its development.

In the interest of balance, a potential problem area from a business and a societal perspective, remains fairness in negotiating the cost of the licence. The much-discussed relationship between user risk (automatic injunction) and patent holder risk (defeat in infringement proceedings/loss of property right) has in fact already led to an adjustment of the law in Germany. I for one am excited to see how patent owners, patent users, the courts and the legislature will respond to future IP asset deals.

The big-bang date for implementation of the new WIPO sequence listing standard ST.26 is fast approaching. All new PCT and national/regional applications filed on or after 1 July 2022 will need to be ST.26-compliant. Ahead of the upcoming changes, we summarise the key considerations and things to watch out for.

In the life sciences and biotechnology fields, many patent offices require a formal sequence listing to be filed with any patent application disclosing nucleic acid or amino acid sequences. The sequence listing includes all the disclosed sequences in a standardised electronic format that allows for easier processing and analysis by patent offices around the world.

The current standard format for these sequence listings – ST.25 – was established by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in 1998, but will no longer be accepted for PCT and national/regional applications with a filing date on or after 1 July 2022. From then, all new filings must comply with the new WIPO standard ST.26.

As there will be no transition period, it is important to be aware of the changes from ST.25 to ST.26 well in advance of 1 July 2022.

Summary of changes from ST.25 to ST.26

One of the major changes in ST.26 is that sequence listings must be in electronic XML format, rather than TXT format. The XML format is designed to improve data compatibility with public searchable databases (including NCBI GenBank and EMBL-EBI) and should therefore make analysis of the sequences by patent offices simpler. As a result of this change, many features must be represented differently under ST.26, compared with ST.25, including:

- Amino acids must be represented by their one letter code, instead of their three letter code

- Uracil and thymine must both be represented by ‘t’, instead of ‘u’ for uracil and ‘t’ for thymine

- Any annotated features will require strictly defined locations

To reflect modern developments in biotechnology, it will now be mandatory to include and annotate:

- Nucleotide analogues (e.g. PNA or GNA)

- D-amino acids

- Linear portions of branched sequences

- The molecule type, which must be further specified beyond DNA/RNA/AA using a defined list (e.g. mRNA, transcribed RNA or viral cRNA)

In addition, sequence listings must no longer include:

- Sequences having fewer than 10 specifically defined nucleotides (i.e. nucleotides other than ‘n’)

- Sequences having fewer than four specifically defined amino acids (i.e. amino acids other than ‘X’)

Full details of the ST.26 standard can be found here.

Key considerations for a smooth transition to ST.26

First and foremost, for any upcoming filings expected to contain nucleic acid or amino acid sequences, it is important to be clear on whether the sequence listing will need to comply with the ST.25 or ST.26 standard.

If a PCT application filed before 1 July 2022 enters the EP or GB phase after that date, ST.25 will continue to apply to the EP or GB application. However, other new filings from 1 July 2022 must comply with ST.26, including new applications claiming priority from an application filed before 1 July 2022, and new European divisional applications.

In some cases, it will be necessary to convert an existing ST.25 sequence listing into the new ST.26 format for use in a new application. For example, the EPO has confirmed that for divisional applications filed from 1 July 2022, which derive from a parent application filed before 1 July 2022, conversion of the parent ST.25 sequence listing into an ST.26-compliant listing will be necessary, along with a declaration that the new sequence listing does not add subject matter beyond the parent application. In contrast, the UKIPO requires sequence listings accompanying new GB divisional applications to be supplied in the same format as the parent application.

Applicants should be aware that additional time may be required to prepare ST.26-compliant listings, or to convert an existing ST.25 listing into the ST.26 format, particularly those which contain sequences affected by the changes, such as:

- Sequences containing nucleotide analogues or D-amino acids

- DNA containing uracil or RNA containing thymine

- Branched sequences

- Sequences with other feature annotations

Moreover, great care should be taken to avoid adding or deleting subject matter when transforming ST.25 sequence listings to ST.26-compliant listings for applications claiming an earlier priority date or European divisional applications. This could be a particular issue if the converted ST.26 sequence listing may be filed at the European Patent Office (EPO), in view of the strict approach taken by the EPO on both added subject matter and priority entitlement.

WIPO suggests that the potential impact of ST.25 to ST.26 conversion should be taken into account when drafting an original (ST.25) sequence listing and application. Of course, in most cases where conversion of an ST.25 sequence listing to ST.26 will be needed, it is too late for that because the ST.25 listing has already been filed. However, if applicants are planning to file a first application before 1 July 2022, they can take steps to avoid future added matter and priority issues in converting that sequence listing to ST.26. For example, features that will become mandatory under ST.26, but which are not covered by ST.25, can be included in the application body as a pre-emptive measure.

Finally, if a sequence listing is filed in the incorrect format, the applicant will probably be invited to file a new listing in the correct format. At least at the EPO, such late filing of the correct listing will incur an official fee. Additionally, only sequence listings filed in the correct format are exempt from official page fees at the EPO. Therefore, an ST.25 sequence listing which is filed as part of an application which is subject to the new ST.26 standard may incur significant official fees (due to the considerable length of most sequence listings). It is worth taking the time to ensure that the correct sequence listing format is used when the application is filed.

The above is not intended to provide legal advice: if you have any questions about how these changes may affect your applications, please get in touch.

Research carried out by Mathys & Squire, around the rise in global patents related to blockchain technology, has featured in an article published by City A.M. – click here to read the feature (p. 14).

An extended version of the article is available below.

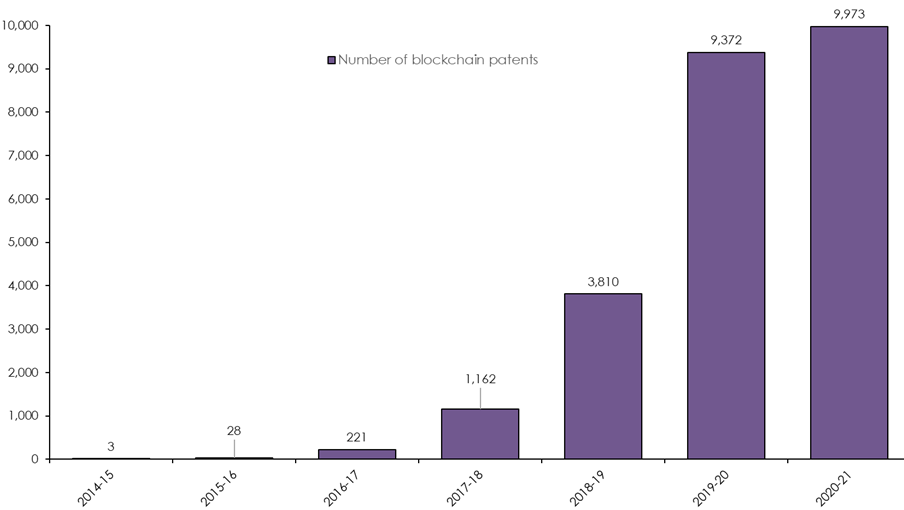

There have been a record 9,973 global patents related to blockchain filed in the past year*, up from 3,810 two years earlier, shows new research carried out by Mathys & Squire.

The rush to secure new commercial applications for blockchain technology is driving R&D in the space. The development of new uses for NFTs and attempts to make core blockchain technology less carbon intensive are particular areas of focus for software houses.

Blockchain technology has the potential to help make supply chain data more reliable and up-to-date. The technology could help eliminate counterfeiting and trace the movement of goods within the supply chain. Possible applications include secure event ticketing and validating ethical supply chains – from organic food to conflict-free diamonds.

Dani Kramer, Partner at Mathys & Squire says: “Blockchain has the capacity to revolutionise sectors as diverse as insurance, healthcare and urban planning. The race to capture new commercial applications is the driving force behind R&D and patent filing in this area.”

“Cryptocurrency is just one element of blockchain technology. It’s a misconception that blockchain is only applicable to cryptocurrency trading or NFTs in the art market.”

Beyond blockchain’s more well-known applications, our research reveals technology for many other potential uses of blockchain has been patented in the last year, including:

- allowing insurers to analyse vehicle sensor data and build user profiles;

- enabling the secure storage and transmission of medical information;

- optimising traffic flows in urban areas; and

- optimising energy efficiency within the power grid.

Fears over crypto carbon footprint drives blockchain innovation

Another key area of innovation in the last year has been to make core blockchain technology greener after criticism of its carbon footprint. In 2019, Bitcoin mining consumed as much energy as the Netherlands**. Earlier this year Elon Musk u-turned on accepting Bitcoin as payment for Tesla vehicles over environmental concerns.

Efforts to make blockchain greener have focused on cryptocurrencies, with alternatives to energy-intensive ‘proof of work’ system of verifying transactions. Proof of work uses so much energy because to verify crypto transfers it requires computers to solve increasingly complex mathematical problems.

Dani Kramer says: “While the environmental impact remains a concern, crypto developers are already coming up with ways to reduce the carbon footprint of cryptocurrencies. Other blockchain applications, for example in the field of energy efficiency, already hold the potential to reduce emissions.”

The majority of blockchain patents for the last year (5,714 – 57% of the total) were Chinese in origin. The US came in second place, with 1,729 (17% of the total). 53 patents originated in the UK – just 0.5% of the global figure. Major filers for 2020-21 include insurance company Ping An, Chinese payment platform Alipay and US technology company IBM.

Number of blockchain patents filed per year

* Patents filed with World Intellectual Property Organization, year ending 30 September 2021

** University of Cambridge and International Energy Agency

In this article for The Patent Lawyer Magazine, Partners Andrew White and Anna Gregson discuss the importance of protecting IP as an asset, even years before commercial use, in one of the largest growth opportunity markets: deep tech.

Deep tech is a term most frequently used in the investment community and tends to refer to businesses that are very research & development (R&D) intensive, using innovative and emerging technologies to solve a particular problem. Deep tech commonly refers to technologies such as advanced materials, synthetic biology, artificial intelligence (AI), or quantum technologies, although many deep tech startups today are combining these technologies – for example where AI and synthetic biology intersect, with 96% of deep tech ventures using at least two technologies. Deep tech companies are therefore very IP-rich, with about 70% of such ventures owning patents related to their products or services.

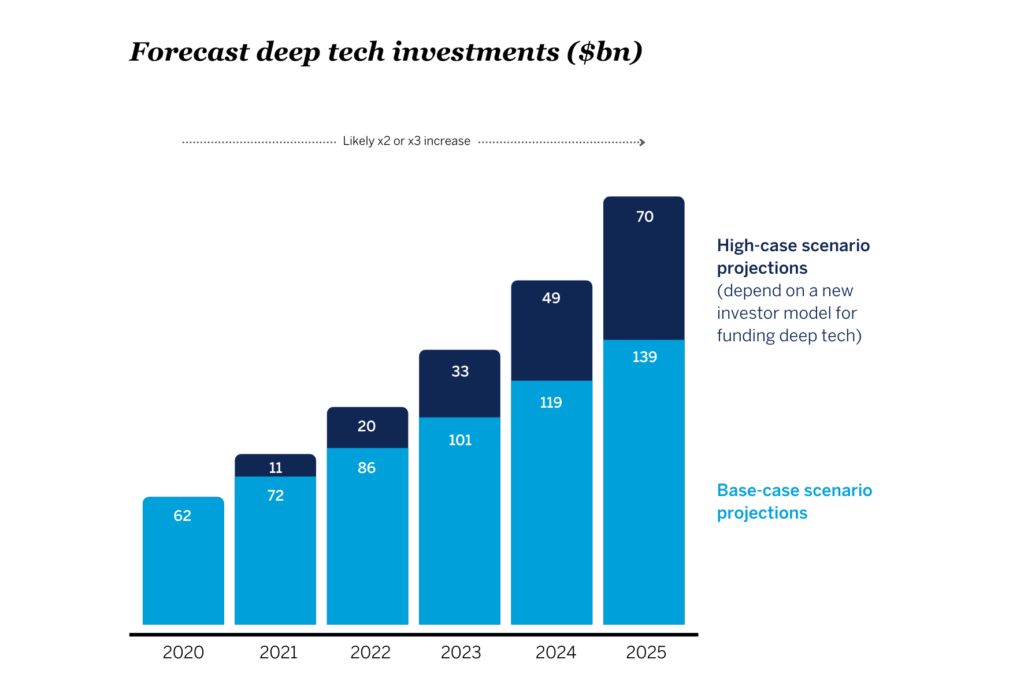

Deep tech is being seen increasingly as a massive growth opportunity. As shown in the figure below, the amount of capital put into this space has grown fourfold, from $15bn in 2016, to more than $60bn in 2020, and it is estimated that deep tech investments will grow to about $140bn by 2025, with investment in AI and synthetic biology attracting two-thirds of deep tech investment last year.

About 83% of deep tech ventures involve designing and building a physical product. Their digital proficiency is focused on using artificial intelligence, machine learning and advanced computation to explore frontiers in physics, chemistry and biology.

(Data taken from https://www.bcg.com/publications/2021/overcoming-challenges-investing-in-digital-technology)

Deep tech companies are likely to be disruptors; incumbent companies, particularly in industries like energy, chemicals and agriculture, will probably be disrupted by deep tech if they don’t engage with this community soon.

As can be seen in the chart below, deep tech companies can also be extremely lucrative, with companies such as Impossible Foods being valued at around $10bn this year:

(Data taken from https://www.bcg.com/publications/2021/overcoming-challenges-investing-in-digital-technology)

Pushing technological frontiers

Deep tech has the potential to reinvigorate established sectors, such as drug R&D, where costs to develop a new drug have doubled each decade for the last 70 years. By providing opportunities to apply tools and principles such as network data science and deep learning to overcome the ‘biology bottleneck’, deep tech has the potential to significantly reduce costs in drug development.

Deep tech also opens the commercial potential of newer sectors, such as synthetic biology, where the confluence of developments in IT, systems theory and biology enables synthetic biology to move beyond the laboratory into commercial use. Despite the emergent nature of synthetic biology, there are already examples demonstrating its scope and disruptive potential, such as designer bacteria capable of producing as diverse materials as precursors for anti-malarials, to spider silk proteins, biologically based logic gates and synthetic organelles.

Why do you need to protect your IP?

Because of their IP-rich and R&D heavy nature, it may be many years before a deep tech startup successfully commercialises its innovation and emerges from the infamous ‘valley of death’. IP may be the only real asset a deep tech startup has for a number of years, so protecting that IP and developing an effective IP strategy is therefore critical to its success.

Investors recognise this and many will want to see a robust IP strategy in place before investing. Deep tech startups need to engage with IP early and often, developing their own IP pipeline (including patents, trade secrets and other relevant IP) and also considering third party IP and freedom-to-operate. Particularly for products where lead times can be long, such as for new drugs that require regulatory approval, a strong pipeline with downstream IP is vital.

Exit strategy

Depending on its business goals, effectively protecting IP can dramatically affect the exit of a deep tech startup. For example, building up a strong and effective IP portfolio can drastically increase the value of the business, whether the exit is via acquisition or IPO. This may yield a higher return on investment for those early-stage investors, as well as the founding team. In the longer term, for many deep tech startups, a strong IP portfolio is also essential because they may be entering and disrupting a crowded and well-established market. Without strong IP in place, they may not be able to survive. If a startup has patents of their own, these can be used defensively; if sued by a well-established competitor, having patent rights of your own can present you with the option to cross-license rather than engage in costly and time-consuming litigation.

To patent or to keep secret?

A common question faced by many deep tech startups is whether to patent at all, or whether to keep their innovation secret in the form of a trade secret. For many, the question comes down to whether a third party is able to reverse-engineer or take apart their innovation and determine how it works. For example, can a user of a software platform understand how an AI algorithm works if all the user does is send some data to a cloud platform, and receive some answers in return? In such cases an effective trade secret policy may be sufficient. One benefit of a trade secret policy is that it doesn’t have to cost lots of money, and it can last indefinitely, provided the secret can be kept. The obvious downsides are that there may be leakage of your trade secrets over time, and by keeping your innovation a secret it doesn’t prevent a third party independently inventing and then patenting their own solution which may in turn limit your ability to work your invention, even if you had been using it prior to their patent filing.

Advantages of a patent are that it encourages investment, collaboration and joint development work, as the patent holder can freely disclose their invention in the knowledge that they are protected by the patent. Patents can also be an indicator of both ownership and technical credibility; they can be used to convince investors that you own the technology that you say you do and that what you are working on is truly innovative.

Partnerships with bigger players

By virtue of their complex and cross-disciplinary nature, many deep tech startups must collaborate to implement their solutions. This presents its own set of challenges and opportunities. For example, the ownership of any resulting IP (often referred to as foreground IP) needs to be established, and for many collaborators they will want a share in this foreground IP. This presents a challenge to the startup who may consider that they hold much of the original (background) IP that attracted the collaborator in the first place.

Deep tech startups should therefore be mindful not only to negotiate a strong and effective IP agreement, but should also consider filing patents before any work begins as part of the collaboration. Filing IP beforehand means it can be pushed into the background IP and therefore the startup can retain ownership of more of the IP in the space.

As with any field, deep tech startups should also be using non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) whenever they discuss any elements of the technology with a third party. However, even if you have an NDA, they are notoriously difficult to enforce and once your idea becomes public it can be very difficult to retain ownership of the innovation. Therefore, if a patent application can be filed even before discussions under an NDA have taken place, this will strengthen your IP position.

Opportunities and challenges

It therefore appears that there are plenty of opportunities for deep tech startups, and the volume of investment pouring in is only set to increase. It is also clear that startups in the deep tech space need to devise and implement a truly effective IP strategy if they are to survive and be successful. For more information on IP specifically relating to startup businesses, visit the Mathys & Squire Scaleup Quarter.

This article was published in The Patent Lawyer Magazine in February 2022.

The European Patent Office (EPO) has announced it will be increasing official fees by approximately 2.5% from 1 April 2022 – two years since its last fee increase in April 2020. Full details of the increases are available via the EPO website.

Those with the largest increase (~3%) include application filing fees and renewal fees, while additional page fees, international search fees and further processing of delayed payments will remain at their current cost. The majority of official fees paid on or after 1 April 2022 will be charged at the new rate (although a six month grace period until 1 October 2022 has been confirmed if an official fee is paid at the pre-April 2022 rate). As stated by the EPO, it will be “deemed to have been validly paid if the deficit is made good within two months of an invitation to that effect from the [EPO]”.

Applicants can save money by paying fees early, ahead of the 1 April 2022 fee increase date, even if the official deadline for paying the fee is not until later in the year. Some fee payments, such as requesting examination and paying renewal fees, can be performed several months ahead of the official deadline so applicants may find it worthwhile to review their patent portfolios to check what fee payments are due over the next few months. A key example that could result in significant savings is entering the European regional phase early (i.e. before 1 April 2022). By doing this, applicants can save up to €115 per application (around 3% of the official fees). Although this would involve attending to the formalities to enter the European regional phase early, it would not bring forward other costs associated with the application as there is no need to request early processing of the application should an applicant choose this option.

We recommend applicants check their pending PCT applications now to decide whether to enter the European regional phase early to take advantage of the cost savings.

For more information about the fee increases and how they may affect your European patent portfolio, and to discuss your options in filing early to save costs, please get in touch with your usual Mathys & Squire attorney, or send us an enquiry here.

Update: 9 March 2022

Having reviewed the final 2022 version which is now in force, there are no substantive changes compared to the preview, which the article is based on. With that in mind, the below summary still stands correct and those changes are still relevant.

The European Patent Office (EPO) has published a preview of its revised Guidelines for 2022, which are due to come into force as of 1 March 2022. While a high-level summary of the major changes has been provided by the EPO, here we discuss some of the changes we consider to be most relevant.

Amending the description

One of the major changes last year was directed to stricter guidance for amending the description. Although the EPO indicated the updates were made to reflect the current process, in practice, much more time and attention is now required to comply with the updated Guidelines.

The EPO appears to have taken on board comments from users as part of the consultation process, at least to some extent, and F-IV, 4.3 has been further revised – although perhaps to not the extent that some may have wished for. For example, instead of requiring the removal (or prominent marking as not being claimed) of embodiments no longer encompassed by the amended claims, it is only subject-matter that is inconsistent with the claims that needs to be deleted (or marked as not falling within subject-matter for which protection is sought).

If an embodiment comprises further features which are not claimed as dependent claims, this is not an inconsistency – as long as the combination of the features in the embodiment is encompassed by the subject-matter of an independent claim.

Examples of inconsistencies are also provided, such as the presence of an alternative feature which has a broader or different meaning than a feature of the independent claim, or if the embodiment comprises a feature which is demonstrably incompatible with an independent claim. Claim-like clauses still ought to be deleted.

The revised Guidelines emphasise further that terms such as “disclosure”, “example”, “aspect” or similar are not sufficient replacements for “embodiment” or “invention” in relation to inconsistencies. However, the revised Guidelines indicate benefit of the doubt ought to be given to applicants where it is unclear if an embodiment is consistent with the claims.

Of course, the revisions were likely finalised before the recent decision in T 1989/18 from December 2021, in which the Board held there is no legal basis in the EPC or elsewhere that requires a description must be amended in line with the claims. The summary of the changes to the Guidelines includes a footnote clearly stating that amendments introduced are intended to remove potential misinterpretation of EPO practice, and that the amendments have been extensively discussed with external and internal users to clarify how the established practice is applied. It seems likely that this will be an ongoing subject, and it remains to be seen whether the decision in T 1989/18 will have an impact on EPO practice.

Priority considerations

A-III, 6.1 provides clarification relating to transfer of priority rights citing T 844/18: where the previous application was filed by joint applicants, all these applicants must be amongst the applicants of the later European patent application or have transferred their rights in the priority application to the applicant of the later European patent application.

A-III, 6.12 is amended to reflect that the EPO now also performs searches for the national offices of Albania and Croatia, and that the EPO now includes in the file of a European patent application a copy of the search results referred to in Rule 141(1), thus exempting the applicant from filing said copy, where the priority of a first filing is made in People’s Republic of China and Sweden.

Finally, F-VI, 1.5 has been revised with further guidance on determining partial priority when only a part of the subject-matter encompassed by a generic “OR” claim is entitled to the priority date of a previous application, in line with G1/15. The revised Guidelines emphasise that, where a part of an application (e.g. EP-Y) already appears in an earlier application (e.g. EP-X), a later application (e.g. EP-Z) cannot validly claim priority from that part (e.g. in EP-Y).

Of course, this year (as reported here) we have recently had the referrals of G1/22 and G2/22 relating to formal entitlement to priority; it is expected that a decision on this will not be issued in time for the next revision cycle of the Guidelines (coming into effect in March 2023), but we will of course update you as soon as there are developments in this matter.

Biological inventions

A-IV, 4.1 now emphasises that for Euro-PCT applications, the document satisfying the EPO that the depositor of a biological material has authorised the applicant to refer to the deposited biological material in the application, and has given unreserved and irrevocable consent to the deposited material being made available to the public, must be provided to the International Bureau before completion of the technical preparations for international publication.

Due to the upcoming implementation of the new WIPO Standard ST.26 for sequence listings that will apply to applications filed on and after 1 July 2022, several sections – in particular A-IV, 5 – have been amended. The changes to the new standard compared to ST.25 are quite extensive and deserve their own separate due care and attention. The revised Guidelines note that detailed information on the changes in practice required by this new standard will be published in the Official Journal of the EPO well in advance.

Relatedly, A-IV, 5.1 provides further clarification relating to the filing of a sequence listing as a missing part of the description under vary rare conditions, and the situations in which this may occur or alternatively in which the applicant will be invited to file a standard-compliant sequence listing. We suggest always referring to SEQ ID NOs, so that if the corresponding sequences cannot be identified in the filed description documents, it is obvious that such sequences are missing.

We also note that there are new examples of matter contrary to morality (see G-II, 4.1) and genetically modified animals as patentable biotechnological inventions (see G-II, 5.2). Finally, further to the extensive edits regarding antibodies in 2021, the description of antibodies has been slightly revised in G-II, 5.6, which now states that instead of requiring all six CDRs to be defined, it is “the number of CDRs required for binding” which ought to be defined.

Technical effects of mathematical methods

Guidance under G-II, 3.3 (Mathematical methods) and 3.3.2 (Simulation, design or modelling) has been updated to reflect G1/19, which confirmed the COMVIK approach for computer-implemented simulations. Further examples have been added, and simulations that are abstract are differentiated from those simulations that interact with physical reality. For the former, the simulation must output data with a potential technical effect, the effect being produced when the data is used in a technical manner. For the latter, a technical contribution can be made regardless the use of results coming from the simulation.

G-II, 3.5.2 (Schemes, rules and methods for playing games) and 3.6.3 (Data retrieval, formats and structures) have also been revised with new examples of technical effects, and G-VII, 5 (Problem-solution approach) also features additional references to the COMVIK approach and G1/19 for mixed-type inventions, including new examples of applying the problem-solution approach to such claims.

Identity checks in oral proceedings

Provisions for checking the identity and authorisations of participants at oral proceedings have been revised, under E-III, 8.3.1, particularly in relation to oral proceedings held by videoconference. Copies of identity documents for parties or their representatives can be filed via EPO online filing options no later than two days prior to the oral proceedings or, at the beginning of the oral proceedings, via email to the address provided to the parties.

The identification must visibly show the full name and picture of the person concerned, but these documents are not made part of the public file. Accompanying persons can have their identity confirmed by the relevant representative.

Inventor/applicant’s location

A-III, 5.3 has been revised to reflect Amended Rule 19(1) EPC (as of April 2021): it is now clearly specified that the country and place of residence may also be that of the applicant (instead of the inventor), in line with commonly accepted practice.

Note that the country and place of residence must be specified, wherein the place of residence is the city or municipality, i.e. not the province or region, where the inventor or applicant permanently resides and should preferably include the postal code.

Extension of time limits

The revised section on the scope of application of Rule 134 (E-VIII, 1.6.3.2), i.e. the extension of periods due to which at least one EPO filing office not being open for receipt of document, now specifically lists some additional periods. These include the opposition period under Article 99(1), the period for entry into the European phase under Rule 159(1), the expiry of the period to pay renewal fees with an additional fee under Rule 51(2), the expiry of the periods under Rule 51(3) and Rule 51(4), the due date for the renewal fees for a divisional application and the beginning of the four-month period under Rule 51(3) and the date of the start of the search.

Revised Guidelines for Search and Examination at the EPO as PCT authority

The Guidelines for Search and Examination at the EPO as PCT authority have also been revised, with the biggest changes in part A.

In particular, A-VI, 6 contains a new section (1.6) on the applicant’s entitlement to claim priority, similar to the changes in the main EPO Guidelines, A-III. Again, where the previous application was filed by joint applicants, all these applicants must be amongst the applicants of the later patent application or have transferred their rights in the priority application to the applicant of the later patent application.

In addition, A-VI, 1.5 now clarifies that if no request for restoration of priority has been filed by the applicant in the procedure before the EPO as RO (if the request has been rejected), the applicant may file a (new) request in the national phase (i.e. in procedures before the EPO as designated Office or any other designated Office).

A new chapter relating to languages has also been added as A-VII, which provides more detailed guidance on admissible languages on filing, international applications filed in multiple language and languages of proceedings and written submissions.

Furthermore, the revised EPO-PCT Guidelines note that the “record copy” transmitted to the IB is considered a true copy (authentic text) of the international application for the purposes of PCT procedures. If a pre-converted document has also been submitted with the international application, it can be used as a fallback in the event of conversion errors.

Summary

It is important to be aware of the revisions that will be applicable from 1 March 2022, in particular the clarifications relating to priority, biotechnology and computer-implemented inventions, and for another year running, amending the description in line with the claims.

The above is not intended to provide legal advice: if you have any questions about how these changes may affect your applications or patents, please get in touch.

Mathys & Squire Partners Anna Gregson, Dani Kramer and Martin MacLean have been featured in the 2022 edition of IAM Strategy 300 Global Leaders.

The guide highlights professionals whose approach to intellectual property is regarded by peers as truly strategic in nature, drawing from the worlds of private practice, consulting and other service providers, with specialists from the major IP markets in North America, Europe and Asia.

IAM says: A perceptive IP strategist, Anna Gregson keeps the wider commercial picture in mind in all her endeavours as a prosecution partner, counsellor and IP protector. She understands her clients at a business level and is brilliant at tailoring her approach and solutions accordingly.

IAM says: Dani Kramer practices at the cutting-edge of innovation in several high-technology fields such as AI, semiconductors and internet television and has been pivotal in securing vital protections for his diverse clients. He understands the how and the why and is both technically adept and commercial.

IAM says: Martin MacLean is a go-to for complex patent briefs thanks to his portfolio management dexterity, striking hit rate in EPO hearings and extensive deal experience. He has a deep understanding of the life sciences industry and its commercial drivers.

We would like to thank each of our clients, contacts and peers who took the time to participate in the research. IAM’s Strategy 300 Global Leaders guide for 2022 is available here.

In a development that could have a significant impact on how priority is assessed in Europe, EPO Board of Appeal 3.3.4 has just referred the following two questions to the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBA) in case T 1513/17 (consolidated with T 2719/19) concerning formal entitlement to priority:

I. Does the EPC confer jurisdiction on the EPO to determine whether a party validly claims to be a successor in title as referred to in Article 87(1)(b) EPC?

II. If question I is answered in the affirmative

Can a party B validly rely on the priority right claimed in a PCT-application for the purpose of claiming priority rights under Article 87(1) EPC

in the case where

- a PCT-application designates party A as applicant for the US only and party B as applicant for other designated States, including regional European patent protection and

- the PCT-application claims priority from an earlier patent application that designates party A as the applicant and

- the priority claimed in the PCT-application is in compliance with Article 4 of the Paris Convention?

The first question asks whether the EPO has the power to determine whether a priority right has been validly transferred. According to established case law and practice, the EPO does have that power, as recently confirmed by Board of Appeal 3.3.8 in the CRISPR/Cas appeal case, T 844/18 (see our news items here and here). However, that power has also been questioned ex officio in communications from other Boards. The failure to introduce priority rights into a European application can of course have devastating consequences for validity, and therefore, if the EBA should answer the first question in the negative, then this would represent a significant relaxation of the EPO’s priority rules. Given established case law, it is possible the EBA will decline to answer the first question.

The second question essentially asks whether naming the applicant for a first filing as applicant for the US only in a PCT application claiming priority thereto is enough for the purposes of introducing priority rights into the European designation. This scenario commonly arises when a US provisional application is filed in the names of the inventors, and a subsequent PCT application is filed naming those inventors as applicants for the US and someone else as applicant for other jurisdictions. EPO opposition divisions have recently been applying what the Board in T 1513/17 calls the ‘PCT joint applicants approach’, whereby the EPO merely checks whether all applicants on a priority application are named as PCT applicants, irrespective of whether they are designated as applicants for Europe or whether priority rights were validly transferred to the applicants for Europe. The Board in T1513/17 concluded that the validity of PCT joint applicants approach is not clear-cut and that guidance from the EBA is required.

It is possible that the EPO will opt to stay pending proceedings in cases where formal entitlement to priority is determinative, following the approach taken in other recent referrals.

We will provide further updates as the EBA referral progresses.

As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic and spending increased time at home, many of us have taken a greater interest in what we eat, which has continued even beyond the banana bread craze of 2020. Consumers have become ever more scrupulous when considering what benefits and harms the food we eat can have, not only to ourselves, but also our planet. It is therefore unsurprising that the biggest food trends we see emerging in 2022 are focused around health benefits and reducing damage to our environment.

Reinventing the coffee cup

If coffee is not only your drink of choice, but also an essential to get you through the working day, you are not alone! In the UK, around 2.5 billion coffees in disposable cups are sold each year. However, only 0.25% of these cups are recycled. Such low levels of recycling are mainly due to the fact that most disposable cups cannot be disposed of in mixed or paper recycling bins. Specialist equipment is required to remove the thin plastic or wax layer present in many cups (providing a waterproof/temperature controlling barrier) before recycling is possible. This process is both costly and time-consuming, meaning that the vast majority of disposable cups end up in landfill sites.

Given the amount of disposable coffee cups used each year and the length of time each cup requires to decompose – for example coffee cups containing polyethylene can take around 30 years to fully decompose – a solution to this problem is urgently needed if we are to continue to enjoy our morning beverage (and for some of us, continue to function like a normal human being!). We anticipate developments in the structure and manufacturing of coffee cups, as well as their recycling, in 2022 as the problem only becomes more pressing.

Biodegradable plastics

Cleantech companies are seeking to tackle this problem by developing biodegradable plastics which degrade in a much shorter timeframe than traditionally used materials. One company looking to provide such a solution is London-based Polymateria Ltd, through the development of a ‘drop-in’ additive containing catalysts and co-catalysts which can be included during the plastic manufacturing process. Following a specified dormant period, the catalysts act to break down both the crystalline and amorphous regions of the plastic, such that the material will degrade to form a wax-like substance without any harmful microplastics being produced. Fungi and bacteria can then fully consume the wax-like material.

Ploymateria Ltd states that its long service life plastic degrades in six months to three years, whereas the short life service plastic will degrade in less than six months – a significant improvement on the materials currently being used.

Edible containers

As an alternative, rather than looking at ways of reducing the degradation time of materials for containers, some companies have focused on developing containers that produce zero waste following their use: enter the edible container. Many startup companies are developing edible packaging and containers from foodstuffs such as rice flour, wheat, potato starch and milk proteins.

London-based startup Notpla has created Ooho, a liquid encapsulated in a waterproof and edible film made from seaweed. Users can eat the film if they wish, or – if that doesn’t appeal – the film will simply biodegrade in four to six weeks.

Notpla’s patent application (WO 2018/172781) states that these edible membranes are formed from alginate, a water soluble biopolymer extracted from seaweed. In particular, alginate is blended with a thickening material, such as starch or cellulose, to form a paste. The paste can then be extruded to form a membrane and a calcium rich ion solution is then added to produce a cross-linked matrix suitable for storing liquids. Of course, multiple layers of the edible membrane can be produced, allowing the consumer to simply remove the outermost layer before consumption, thereby overcoming the need for additional storage containers for hygiene reasons.

Whilst this invention represents an exciting step forward, for such containers to become fully integrated into everyday life, it may be necessary to develop resealable containers which can store greater quantities of fluids.

One particular product which has been immediately integrated into our everyday life is the edible coffee cup. Many startup companies are developing such products, including Scottish startup Biobite, Bulgarian based Cupffee, Ukrainian company Lekorna and Moldova-based Wayris. These edible coffee cups typically comprise a wafer or biscuit based cup which has been developed to prevent the immediate absorption of the liquid they contain. Depending on the brand selected, the edible cups reportedly stay crispy for between 20 and 60 minutes and can remain leakproof for up to 12 hours.

It has been estimated by a transparency market research company that the demand for edible packaging could increase on average by 6.9% yearly until 2024, at which time the edible packaging market would be worth almost $2 billion worldwide. On this basis, and the fact it is always nice to have an extra snack, we are expecting to see many more edible containers emerging over the next year.

Potato milk

Over the last few years, there has been a sustained increase in the number of people turning to vegetarian and vegan diets, or simply reducing the amount of animal-based products they consume. The main drivers for these lifestyle changes include health, environmental and economic reasons. Food and drink manufactures have responded to the increased demand by developing a range of exciting plant-based products. Amongst these are the plant-based alternatives to milk, including rice, oat, almond, soya and pea. However, there have been some reports suggesting that these plant-based alternatives may still be damaging to the environment. For example, almond production requires high water consumption which can lead to droughting effects, as well as carbon emissions resulting from the need to transport these drupes from the countries in which they are grown. Similarly, rice production requires large volumes of water and can be associated with the production of greenhouse gases due to the presence of methane-producing bacteria, which grows in the waterlogged soil of rice paddies. In addition, some of the dairy-free milk products produced are not suitable for those with allergies.

To address some of these issues, a new plant-based milk is expected to gain momentum in 2022: potato milk. Considered to be more environmentally friendly as it requires less land to grow the product, potato milk also produces less CO2 (thanks to the ability to grow these vegetables locally), and requires significantly less water than some other milk alternatives. Potato milk does not contain any added sugar, gluten, lactose or soya and can provide health benefits in the form of vitamin D, B12 and folic acid.

In February 2022, Waitrose is set to begin selling the potato milk brand ‘Dug’, owned by Swedish company Veg of Lund. According to a patent application of Veg of Lund (WO 2020/112009), the milk alterative is a potato emulsion comprising of (unsurprisingly) potatoes, sugar, a vegetable emulsifier, oil, vegetable protein and water. Whilst we always encourage the development of new food and drink products, only time will tell if this new product will take a significant share of a market which has been reported to be worth nearly £400 million a year in the UK alone.

CBD wine

The demand for CBD-based products has been growing in recent years as a result of a change in consumer perception (cannabidiol, a non-psychoactive compound found in the flower of the cannabis plant). This compound has now become associated with numerous health benefits including treating medical aliments, such as Alzheimer’s, epilepsy, pain, stress and anxiety. This shift in consumer perception of CBD-based products is due, at least in part, to the increasing amounts of medical research on the effects of CBD and the rising publicity of the health benefits associated with the compound.

In the UK alone, the CBD market is estimated as being worth £300 million and is expected to increase up to as much as £1 billion by 2025. As a result, companies in the food and drink industry have been quick to provide a variety of CBD-infused products in order to meet this new demand. The latest product to emerge from this trend is CBD-infused wine, which is expected to be popular with consumers this year. CBD wines typically have a lower alcohol content, meaning that consumers generally intake lower amounts of alcohol, providing further health benefits.

Chewable toothpaste

Although not strictly within the food and drink category, chewable toothpaste is set to be a big trend in the next year. As it turns out, recycling toothpaste tubes is actually quite tricky due to the fact that the tubes are often made out of different types of plastic and contain a metal liner to keep the toothpaste fresh. These waste containers are therefore often too complex to recycle at present. A further concern related to the currently manufactured toothpaste tubes is that they form microplastics during degradation, which can be damaging to the environment. Due to growing awareness of the pressures on landfill sites, consumers are now looking to alternative containers or products that will enable them to reduce the amount of plastic waste produced.

An emerging alternative to traditional toothpaste tubes are chewable toothpaste tablets. These solid tablets can be chewed into a paste before the user brushes their teeth with a damp toothbrush in a similar manner to that of traditional toothpaste. According to some reports, the global toothpaste tablet market could be worth US$152.3 million by 2026. The main selling point of these products is that they can be provided in glass or recyclable plastic bottles, and therefore are more environmentally friendly. Chewable toothpaste tablets typically comprise common ingredients found in toothpaste, such as xylitol, calcium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, tartaric acid derivatives and fluoride.