A recent decision by the Boards of Appeal at the European Patent Office (EPO) looks at the exceptions to patentability under Article 53(c) EPC, and how they apply to method claims which do not explicitly recite a treatment step.

Article 53(c) EPC excludes from patentability methods for the treatment of the human or animal body by surgery or therapy, as well as diagnostic methods practised on the body.

In the present case, the claims relate to a method of managing delivery of an orthodontic ‘treatment plan’, and recite steps performed before and after administration of orthodontic appliances to a patient (notably, the claims do not recite the administration step itself). During examination, the Examining Division refused the application under Article 53(c) EPC on the basis that the claims “implicitly comprise an orthodontic treatment step”.

During the appeal proceedings, the Applicant acknowledged that the unspecified administration step was a prerequisite for performing the method, but (citing G 1/07 and T 329/94) argued that the absence of an explicit administration step meant that the claims do not fall foul of Article 53(c) EPC.

The Board disagreed with the parallels drawn between the present invention and with G 1/07 and T 329/94. Whereas G 1/07 and T 329/94 dealt with cases in which there was no functional link between the claimed method and the effects produced by the device on the body, the presently claimed method steps were deemed to be functionally linked with (and incomplete without) the administration step.

The Board noted that “it is not necessary for a claim to explicitly (…) mention a therapeutic method step (…) to be excluded from patentability. It is sufficient that the claimed method encompasses such a step (see G 1/07, grounds 4.1 to 4.3…)” (see Reasons, 1.2). The unspecified administration step was therefore held to be an essential feature which must be taken into account when assessing Article 53(c) EPC.

The Board therefore agreed with the Examining Division and maintained the decision to refuse the application under Article 53(c) EPC.

Although the Unified Patent Court (UPC) is anticipated to open its doors around March 2023 and European patent holders and applicants are busy reviewing their European patent portfolios to decide whether to opt out of its jurisdiction, the ability to formally select Unitary Patent protection is not yet available.

The transitional measures of the EPO – delay of grant as well as an ‘early request for unitary effect’ (for details, please click here) – will only come into force once the so-called sunrise period starts. This will be three to four months prior to the start of the UPC. Neither of these dates have ultimately been confirmed yet.

Thus, if you have already received your 71(3) communication, you will need to rely on other intervening measures if you want to have the opportunity. Such measures may make it possible to bridge the time until the transitional measures are in place. Whether or not this is possible for you will depend on the individual circumstances and details of your case and will need to be evaluated and discussed on a case by case basis.

Leading intellectual property law firm Mathys & Squire has announced a series of Partner promotions and two new Managing Associates. The promotions form part of the firm’s growth strategy and reflect the firm’s commitment to professional development and career progression.

Alan MacDougall says: “We are delighted to announce these promotions following a very strong year for Mathys & Squire. Our new Equity Partners, Partners and Managing Associates have all played a crucial part in Mathys & Squire’s recent growth and successes. They have the proven knowledge and experience to deliver for our clients and help continue the growth of the firm.”

In recognition of their contribution, the following Partners have been promoted within the equity partnership:

- Dani Kramer (London) – Dani manages the international patent portfolios of large corporates, focusing on fields such as software, AI and machine learning, as well as electrical and electronic engineering.

- Catherine Booth (Manchester) – Catherine works across the technical fields of healthcare, engineering, and telecoms. Her practice includes the creation and management of IP portfolios, litigation and other disputes.

- James Wilding (London) – James’ practice includes European Patent Office prosecution and opposition work in the life sciences sector. He has particular expertise in immunology, vaccines and gene editing.

- Andreas Wietzke (Munich) – Andreas has significant experience in obtaining, defending and enforcing national and international patents, with technical expertise spanning the fields of software, telecoms, medical devices and mechanical engineering.

The firm is also pleased to announce two Partners have been promoted to Equity Partners:

- Andrew White (London) – Andrew manages international portfolios in the medtech, software, telecoms and automotive fields. He is an expert in deep tech inventions in fields such as AI and blockchain, as well as technologies related to consumer healthcare.

- David Hobson (London) – David has a background in biochemistry and advises clients within the biotechnology, pharmaceutical and food & beverage sectors. He has extensive experience in patent drafting and multi-jurisdictional prosecutions.

Annabel Hector and Alexander Robinson have been promoted and are now Partners. Annabel has experience in litigation with her technical expertise spanning the fields of mechanical and structural engineering. Alexander’s experience includes the defence of commercially significant patents against multi-party oppositions. His technical expertise lies in chemical sciences and pharmaceuticals. Both Annabel and Alexander are London-based.

Edward Cavanna and Thomas Fraser are newly promoted Managing Associates in Mathys & Squire’s London office. Edward is experienced in drafting and prosecuting UK and European patent applications, especially in the fields of software, materials and green energy. Tom’s technical expertise lies in IT and electronics, including AI and machine learning. His practice includes drafting and prosecuting patent applications in the UK, Europe and US.

Alan MacDougall says: “We are passionate about providing our employees opportunities to maximise their potential and are delighted to offer them a promotion and the recognition they deserve. Mathys & Squire is proud to have them on our team and is looking forward to continuing to grow our practice together.”

Serving legal proceedings can be a necessary, but potentially troublesome legal requirement – and using the usual methods of service (personal service, first class post, leaving at a specified place, or via electronic communication) can be particularly tricky in situations where potential defendants are being purposely evasive. A recent decision from the UK High Court offers an alternative method, albeit one that is applicable only in very specific circumstances.

In this decision (D’Aloia v Binance Holdings & Others [2022]), Fabrizio D’Aloia has been allowed to serve proceedings via non-fungible tokens (NFT) airdrop to a digital wallet. The background to the case is that Mr D’Aloia had transferred a large number of cryptocurrency tokens to a purported trading account, which he later realised was fraudulent. Mr D’Aloia was able to trace these tokens to digital wallets associated with Binance (among other exchanges). Thereafter, in an attempt to recover these assets, D’Aloia sought an injunction and also sought – and was granted – permission to serve the (unknown) owners of the digital wallets via NFT airdrop to those digital wallets as well as via email.

This ruling thus enables the contacting of parties of unknown identity or address in a straightforward manner via NFT airdrop. At the present time, there seem to be rather limited circumstances in which this method might be applicable, specifically in cases of cryptocurrency misappropriation. However, if blockchains become more pervasive through society in the coming years – and more people have links to known digital wallets – this method of service might become more widely applicable. One could imagine a future in which various types of legal proceedings are served by NFT Airdrop to a wallet associated with a defendant. And this sort of rapid and undeniable service of proceedings via NFT, which would leave an immutable record on a blockchain, would offer immediately apparent benefits over the slower and more difficult to evidence service of proceedings via post.

A similar ruling was made earlier this year in the US in LCX AG, -v- John Does Nos. 1 – 25, so perhaps more countries will follow soon.

Although these cases are of course not relevant to the patenting of blockchain technology, these decisions do at least indicate that blockchains are being used for an increasingly diverse range of purposes and are increasingly finding acceptance from governmental bodies. One slightly tangential takeaway then from a patent point of view – that is particularly relevant in the UK (which currently takes a harsher view of blockchain applications than other jurisdictions) – is that it is worthwhile for applicants to think about potential (non-cryptocurrency) uses of blockchains and to describe these uses in any patent application. Linking blockchain technologies to practical uses will often be helpful for avoiding subject matter objections in patent applications.

Data provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in articles by The Manufacturer, The Resource, Circular Online and The Patent Lawyer providing an update on Chinese companies leading the charge for ‘holy grail’ of clear recycled PET.

An extended version of the release is available below.

A record 2,149 patents for plastic recycling were filed last year, up 7% from 2021 and an eightfold increase since 2016, says Mathys & Squire, the intellectual property firm.

Mathys & Squire says the plastic recycling industry is competing to develop technology that will produce clear recycled plastic. Current recycled plastic has a yellow or grey tinge, unlike the clear colour that consumers expect of a premium product.

A vast range of methods for separating and sorting clear recycled PET is being tested, including the use of fans, centrifuges, lasers and optical lenses. The main priority is to achieve a higher quality ‘feed’ of recycled plastic that will provide the desired lack of colour.

Global brands are searching for a source of clear recycled plastic due to consumer and regulatory pressure to reduce or even eliminate virgin plastic from their supply chains. Coca-Cola and Pepsi have each pledged to use at least 50% recycled PET by 2030.

85m tonnes of PET plastic is produced globally per year. Mathys & Squire says that given the pressures on corporates to use more recycled PET, the company that perfects clear recycled plastic stands to generate very large revenues from licensing its technology.

Chris Hamer, Partner at Mathys & Squire said: “The race is on to develop the holy grail of cost-effective, clear recycled PET. That is the key driver behind the surge in innovation we have seen in this area.”

“Stakeholders are increasingly demanding low-carbon products, which in turn is creating a huge market for recycled plastics.”

“Whoever can develop a cost-effective method of producing clear recycled plastic will be able to tap into what some major players estimate to be a potential £100 billion market.”

Last year Chinese companies filed 1,970 patents relating to plastic recycling, 1,937 more than second place India. China is leading the way in patent filings as the country is in the middle of a single-use plastic crackdown.

In July of last year, China’s National Development and Reform Commission which oversees economic planning of mainland China published a “five-year plan” to boost plastic recycling and incineration capabilities. The five-year plan also commits to greatly reducing the use of single-use plastics.

Community design regulation (CDR) dictates that “A community design shall not subsist in features of appearance of a product which are solely dictated by its technical function” (Article 8(1) CDR). The rationale behind this, as indicated by the EU Design Directive, is to prevent technological innovation being hampered by design protection – such innovation should instead be protected by patents, which of course enjoy a shorter term, and are required to undergo substantive examination before grant.

It goes further to say that a design shall not subsist in features whose “exact form and dimensions” are required for the product “to be mechanically connected to or placed in, around or against another product so that either product may perform its function” (Article 8(2) CDR). This allows for free competition to provide and purchase products which fit to other products.

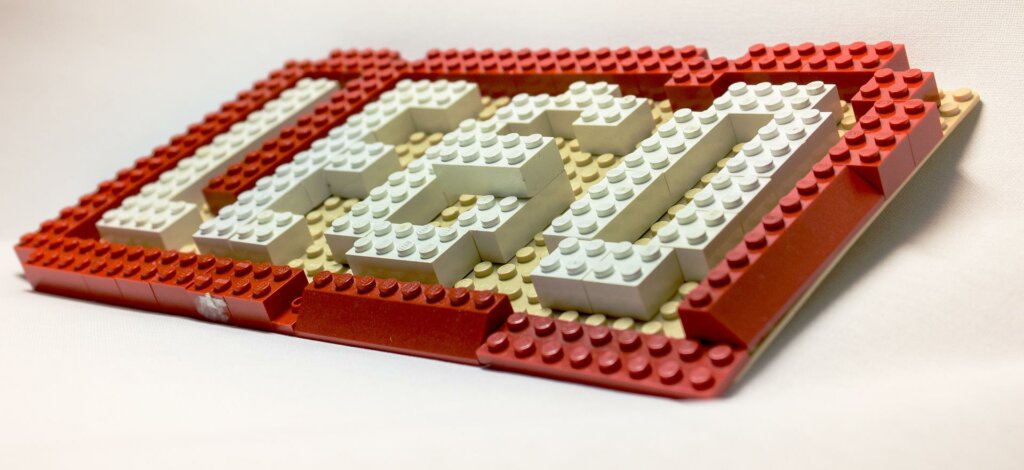

However, the situation becomes a little more complex when considering modular products, which can be assembled in a variety of manners. An important aspect of the design of such products naturally relates to how they can be fitted together. The Regulations therefore include an exemption that a design shall “subsist in a design serving the purpose of allowing the multiple assembly or connection of mutually interchangeable products within a modular system” (Article 8(3) CDR), a caveat which has gained the moniker ‘the LEGO Exemption’.

However, a product can fall under the remit of several of these paragraphs, and it may not always be clear just what can be registered. A recent judgement by the EUIPO’s Board of Appeal (following a judgement by the General Court) has considered the relationship between the technical function of a design and its modular nature – fittingly – in relation to LEGO bricks.

A design relating to a LEGO building block was previously declared invalid by the EUIPO Board of Appeal as its features were considered to be “solely dictated by their technical function”. The General Court since annulled this decision, stating that the Board of Appeal must consider the exemption for modular products (Article 8(3) CDR).

Upon reconsidering the case, the Board again decided that the design did indeed fall within the scope of both Article 8(1) CDR and Article 8(2) CDR, as its features are “solely dictated by its technical function” and having exact “form and dimensions … to be mechanically connected to or placed in, around or against another product so that either product may perform its function”. However, this time it was not the end of the matter.

The Board was then compelled to determine whether the design fulfilled the exemption of Article 8(3) CDR relating to modular systems. Citing that the bricks “can be assembled with, and disassembled from, other bricks of the set in different ways to build numerous varying creations”, it was decided that this exemption was indeed fulfilled, and therefore the design registration was deemed to be valid.

This decision is perhaps unsurprising, the Board themselves even stating that “LEGO bricks are probably the best-known example of such a modular system”. It therefore seems likely that LEGO systems will continue to act as a guiding example of when this exemption may be applied, and it will be interesting to see what other modular systems will also be considered to fall within this ‘LEGO exemption’. From a broader perspective – this decision also seems in line with the intended purpose of Article 8(3) CDR – as, indeed, it seems only just that designers of clever and complex interconnecting systems be fairly rewarded.

(C) Naomi Korn Associates & Mathys & Squire 2022. Some Rights Reserved. These case studies are licensed for reuse under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike Licence.

The following case study has been taken from the “Implications of Covid-19 on SMEs – reassessing the role of IP in multiple sectors and industries” report written by Naomi Korn Associates and Mathys & Squire Consulting, November 2021. This case study reviews the impact on SMEs (small, medium enterprises) of the COVID-19 pandemic since its appearance in early 2020 through the first quarter of 2021. It focuses on the industries most affected by the crisis and whether intellectual property (IP) and IP management may have helped mitigate its impact through adaptation and change.

Sector overview

While many industries and sectors have seen consumer demand plummet and have been faced with furloughing and layoffs, the wider healthcare and medical sectors have faced extremely high demand for services. Requirements for social distancing and minimising contact have seen the rise of new innovations surrounding robotics and telehealth solutions. Transformative developments using blockchain technology, allowing for exchange of information across products, services and medical practitioners have also experienced an increase in innovation. This is evident thanks to the announcement of Healthcare Innovator Philips that it is investing in a pivot towards telehealth. In the post-COVID-19 world, a permissioned and private blockchain will have a pivotal role in the digitisation of the healthcare industry and creation of new digital health solutions.

Analysis

While telehealth technologies were already present, it has been estimated that the level of telehealth visits has increased by 50-175 times the pre-COVID-19 levels with many patients now viewing the technology favourably. Many institutions have retrained their staff to provide innovative telehealth services, including virtual patient waiting rooms, robotics, connections to peripheral devices for remote diagnostics, cloud based clinical trials and electronic prescriptions services. This represents a change in the business model used in the sector, with up to 76% of surveyed patients indicating that they would use telehealth technology moving forward. For example, the Singapore-based startup Homage, matches families and caregivers, providing home visits, telehealth consultations and medications delivery, through an integrated platform accessible by patients, medical staff, and other care providers, and keeping medical information, and prescriptions all in one healthcare management tool. The US company Radiologex offers a blockchain-based healthcare ecosystem, called R-DEE – a dedicated industry product for global healthcare that enables easy and secure communication and collaboration for all users.

The present pandemic has catalysed interest in contact-free continuous monitoring (CFCM) devices and approaches, such as the virus screening platform Clearstep, which allows patients a user-friendly way to check their symptoms, exposure and risk levels, and receive tailored advice and routes for potential care. Such approaches allow for a limitation of physical contact, reduction in in-person contact and the need for medical staff to gown up. It is estimated that 5% of COVID-19 patients may require ICU treatment, and with an ever-increasing infection rate, and coping with a reduced workforce, telehealth technologies offer medical staff a route to treat those infected, while reducing the chance of further transmission or quarantine requirements. The Israeli company Earlysense has developed CFCM technology for continuous patient monitoring, including heart rate, respiratory rate and motion monitoring, as well as dashboards for overview of activity per patient or even per facility. We note that in February 2021 this technology was acquired by US-based technology company Hillrom, with the company licensing the technology back to EarlySense who will continue to make new developments, including next-generation AI based sensing technologies for remote patient care.

Tele-ICU technology has enabled remote consultations, thereby taking off some of the pressures associated with limited staff and PPE shortages. Research has shown that such systems may result in a reduction in mortality rates by 15%-60% and a significant reduction in the length of hospital stays[1]. This advantage continues beyond this point with telehealth allowing continued monitoring of recovered COVID-19 patients once they have left medical facilities. This seismic impact of COVID-19 on the healthcare sector has resulted in a telemedicine market worth more than $49.9 billion, expected to increase by a CAGR of 40.4%, reaching a value of $194 billion in 2023. The United States represents the largest market, followed by Asia Pacific and Europe.

In this sector, numerous companies, medical facilities, and inventors have developed novel solutions. Prior to the pandemic, a US-based company had developed a cloud-based, HIPAA-compliant platform called Vidyo to conduct patient consultations and to communicate between physicians and hospitals. However, with the arrival of COVID-19 several healthcare providers in the US found that with additional hardware, this already approved system could be easily rolled out across the hospital. French company Tessan has developed a connected telemedicine cabin, which has been already installed in several pharmacies in France. These cabins are fitted with several medical devices and remotely connected to doctors, who can act based on the output when required, without the need for the patient to enter the hospital. The pandemic has also sparked the development of Iceland’s SidekickHealth, a gamified digital therapeutics platform combining clinical validation with gamification, behavioural economics, and AI to deliver a personalised patient experience. Companies have also stepped up to offer royalty free licensing of patented technologies to healthcare providers through the Open Covid Pledge to aid in the fight against COVID -19. This includes patents relating to a variety of technologies including network-based healthcare information systems from AT&T, Wi-Fi enabled open-clinics from Hewlett Packard Enterprise, disease diagnostics technologies from Fujitsu, and protein detection technologies from Sandia.

A recent lawsuit filed by Teladoc Health against American Well over infringement of robotics and real time connection patents is a testament to the increase in patent litigation amongst telehealth companies and providers. It also highlights the importance of securing suitable protection of intellectual property assets from the beginning, especially when regulations are being relaxed to ease provision of care for patients.

The technical innovations used to provide telehealth services are rich in data, with the AI models they contain being trained on data generated by sensors, apps, and patient interactions. One of the main points of concern in the use of these technologies relates to data protection and its secure storage, as well as many innovations being developed in their own right just to deal with these issues. Telehealth solutions and the related data provide a wide range of intellectual property assets, which should be suitably protected.

A well-known telehealth platform may be recognised through a known trade mark or logo, while the software behind the platform may be copyright or in some cases patent protected. Algorithms behind a certain telehealth software are likely to be protected as trade secrets, whilst user interfaces or layouts may be protected by design rights. In all cases, such telehealth platforms represent a mix of intangible assets, which must be carefully managed by any business operating in this sector. Furthermore, the move towards telehealth and blockchain enabled systems, represents the formation of new business models, leaving existing players needing to strategically pivot their strategies to focus on more innovative opportunities[2].

[1] Naik, Gupta, Singh, Soni, & Puri, 2020, pp. Real-Time Smart Patient Monitoring and Assessment Amid COVID-19 Pandemic – an Alternative Approach to Remote Monitoring

[2] Morgan, Anokhin, Ofstein, & Friske, 2020, p. SME response to major exogenous shocks: The bright and dark sides of business model pivoting

Naomi Korn Associates is one of the UK’s specialists in copyright, data protection and licensing support services.

Mathys & Squire Consulting is an intellectual property consulting team that can support all businesses in capitalising intangible assets.

Naomi Korn Associates and Mathys & Squire Consulting are working in partnership across multiple industries to provide innovative consultancy IP support services.

Following the launch of a consultation on intellectual property (IP) and artificial intelligence (AI) towards the end of last year, the UK Government have now released their formal response summarising the outcome.

The consultation was designed to seek opinions on the issues surrounding IP – in particular copyright and patents – and AI as a tool for innovation and creation.

Three key areas were looked at:

- Copyright protection for computer-generated works without a human author. These are currently protected in the UK for 50 years, but the consultation looked at whether they should they be protected at all, and if so, how.

- Licensing or exceptions to copyright for text and data mining, which is often significant in AI use and development.

- Whether and how AI-devised inventions should be protected by patents.

Several options were presented for each area and respondents were asked to indicate which of three options they would prefer, where “option 0” for all three areas represented “no legal change”.

Based on the results of the consultation, the UK Government are not planning any changes to UK patent law or copyright laws relating to computer-generated works, though notes that they will keep these areas of law under review.

The UK Government is, however, planning to introduce a new copyright and database exception which allows text and data mining for any purpose. Rights holders will still have safeguards to protect their content so they can choose the platform where they make their works available, and charge for access.

We will continue to monitor for updates and will of course provide more information relating to any changes as we become aware of it.

Data provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in articles by City A.M. and The Patent Lawyer providing an update on the launch of the Unified Patent Court.

An extended version of the release is available below.

Europe’s new one-stop shop for IP enforcement – the Unified Patent Court – took a major step forward on Friday 8 July 2022, as 90 new judges began to be informed that their applications to sit on the court have been successful. Mathys & Squire, the leading intellectual property law firm, says that the Unified Patent Court is no longer a distant prospect but an imminent reality for businesses and inventors in the UK and across Europe.

The Administrative Committee of the Unified Patent Court received over 1,000 applications from judges across Europe. Of these, 90 have been selected to serve on the court.

The new court will serve as a single point of contact for litigation of IP infringement within participating countries – which could potentially save businesses thousands in legal costs.

After many years of delay, the Unified Patent Court is finally taking shape. First agreed in 2013 – but subject to numerous delays in domestic ratification – the court will soon clear one of its last major hurdles on the road to full implementation.

Andreas Wietzke, Partner at Mathys & Squire says: “The letters being sent out from now onwards will give the Unified Patent Court what a court needs most – judges. The UPC has been on the horizon for decades but now finally is taking shape.”

“UK & European businesses which have long been looking forward to a simplified and cost-efficient patent litigation system can now be increasingly confident that this is just around the corner.”

“Businesses now need to prepare for the UPC to become a reality and work out their strategy for maximising their IP protection across Europe.”

Mathys & Squire is delighted to be ranked in the latest edition of the IAM Patent 1000: The World’s Leading Patent Professionals 2022 directory – the ‘go-to’ guide identifying ‘top patent professionals in key jurisdictions around the globe’. The guide is compiled based on feedback following an extensive research process involving around 1,800 interviews over five months.

Aside from our firm ranking, ten of our Mathys & Squire attorneys have been recognised as Recommended Individuals: Partners Paul Cozens, Martin MacLean, Alan MacDougall, Jane Clark, Chris Hamer, Andrew White, Dani Kramer, Anna Gregson, Craig Titmus, as well as James Pitchford.

Our attorneys have been praised as a “forward-thinking and technically skilled team with a dedication to premium client service”. We are pleased that “Mathys & Squire has maintained its position as a top choice for patent prosecution across the United Kingdom and Europe.”