From developments in the world of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), to the exploration of space, there have been numerous advancements and trends in the fields of science and technology that have garnered attention. IP has played a crucial role and has allowed innovators to reach new horizons with the help of IP protection. In this article, we have focused on some of the most exciting and influential trends that have dominated throughout 2022.

Artificial intelligence and progress in patentability

AI and ML have gone from strength to strength in the last couple of years – and the development of these technologies shows no sign of slowing down. Moving forward, it is clear – as it has been for a while – that AI will play a considerable role in our everyday lives. With these types of technology becoming progressively more commercialised, and with an increasing number of AI/ML patent applications making their way through the various patent offices, there is an escalating amount of consideration of the patentability of these technologies. For example, the UK Intellectual Property Office has recently released a guidance note on the protection of AI inventions. While this guidance note is far from perfect, it is an indication of the desire for patent offices to provide more concrete guidance for an uncertain area. As AI/ML patent applications become increasingly commercialised, we might expect to see a commensurate number of court decisions that provide further guidance for applicants.

Free-from sector continues to grow throughout 2022

The market for free-from products, which include non-dairy milk, low or no-alcohol beverages, and meat alternatives, has seen significant growth throughout 2022 due to a variety of factors. This includes health concerns, increasing awareness of food sensitivities, and concerns about the environmental impact of traditional meat and dairy products. This market is now predicted to be worth $1 trillion by 2026. Leading companies, like Unilever, are looking to significantly expand their offerings in this space in order to compete for some of this ballooning market share. As a result, there is expected to be intense competition among established free-from brands, new entrants, and traditional food and drink companies hoping to enter the market. However, as the cost of living rises, innovation relating to more cost effective methods of producing these products may come to the forefront.

Brands in this growing market are becoming more aware of the effectiveness of IP in safeguarding their market share. For example, on 9 March 2022, Impossible Foods Inc started infringement proceedings against Motif FoodWorks. Impossible Foods considers Motif’s sale of HEMAMITM – a bovine myoglobin composition which “tastes and smells like meat because it uses the same naturally occurring heme protein”, along with burgers produced containing the HEMAMITM molecule, to infringe the claims of their patent. In response, Motif FoodWorks has requested a review of the validity of Impossible Food’s patent. In addition to the legal risks, brands must also consider the potential impact on their reputation when pursuing litigation, as exemplified by Oatly’s unsuccessful suit against Glebe Farm Foods, which led to negative publicity and social media backlash. As the free-from market continues to expand, the potential for intellectual property disputes will also increase. While legal action may be necessary in some cases, the cost of litigation is a factor to be taken into consideration. Depending on the facts of the case, alternative methods for resolving disputes may be worth exploring.

Blockchain – is there a chance of a crypto comeback?

Publicly traded cryptocurrencies have suffered huge losses in the past few months, and several prominent exchanges have collapsed, so at first glance blockchain might seem to be a doomed technology. However, blockchain continues to be an area of interest across many industries and a substantial number of patent applications are still being filed for this technology. While the days of rampant speculation and valuations built on hype alone seem likely to be at an end, there does still seem to be potential for blockchain technologies to make it to market.

While cryptocurrencies and blockchain are synonymous to much of the population, many blockchain innovations – and patent applications – are not directed towards cryptocurrencies, so even if the cryptocurrency markets do not recover there is no reason to think the recent troubles are a death knell for all blockchain technologies. And from an IP point of view, the increased scrutiny of blockchains might well increase the relevance of patent protection. With hype and good marketing no longer being sufficient to gain the attention of investors, evidence of innovation is likely to become an ever more important factor in bringing blockchains to market.

Personalised therapies are on the rise

2022 has been another exciting year for personalised cell immunotherapies. These take immune cells and modify them so that they can kill cells in the body associated with a disease. To date, they have normally used the patient’s own cells, but this year saw important steps in the development of treatments based on donor cells. These have long been sought after, as they remove the need to tailor an individual’s own cells, and allow treatments to be made available faster, and potentially for a larger number of patients.

Two stories of particular interest occurred at the end of the year. Base editing was successfully used for the first time to create modified T-cells that provided a therapy for a patient with otherwise untreatable T-cell leukaemia. The complex approach was needed to allow the modified cells to kill cancerous T-cells, but not damage each other. The treatment proved a great success, and appeared to completely eradicate the cancer. In other exciting news, the European Commission issued the world’s first marketing authorisation for an ‘off the shelf’ T-cell immunotherapy based on modified cells obtained from healthy donors.

Climate change continues to spark clean tech development

In 2022, we have seen the continued growth of clean tech, with particular developments in clean energy generation and technologies to adapt to the impact of climate change. One of the most notable technological developments has been the recent announcement that scientists at the National Ignition Facility have achieved nuclear fusion ignition, producing a hydrogen fusion reaction that released more energy than was required to initiate the reaction. This is a significant milestone towards building the first nuclear fusion power plant which – if achieved – could produce energy without releasing greenhouse gases and without generating the radioactive by-products associated with nuclear fission power.

Technological trends in clean tech are also likely to be influenced by the outcomes of the COP27 conference, especially the agreement regarding a ‘loss and damage’ fund for vulnerable countries. The fund will help developing nations adapt to climate change by financing innovation in areas such as sea defences or breeding crops that can better withstand drought. All these adaptations will require fast paced innovation to help keep up with the implications of climate change, leading to an increase in inventions and patent applications relating to climate adaptation technologies.

Unified Patent Court makes great strides – prepare for 2023 launch

Following a series of setbacks and delays in previous years, 2022 was a year in which the long-awaited Unitary Patent (UP) and Unified Patent Court (UPC) finally began to pick up momentum.

The year began with Austria becoming the thirteenth country to formally ratify the Protocol on Provisional Application, a necessary move to allow the final stages of preparatory work for the UPC to commence. These included the official recruitment and appointment of judges and court staff, and the finalisation of the Court’s IT systems. Selection and appointment of judges took place, with the final list (barring two remaining vacancies) being made public in October. However, some questions remain as to how conflicts of interest will be managed given the fact that the judicial appointments include a number of practitioners working in-house or in private practice, who will be permitted to act as UPC judges on a part-time basis.

Another significant development took place when the Netherlands pulled out of the race to host the section of the UPC’s Central Division which had originally been destined for London. This leaves Italy – specifically, Milan – as the only publicly-declared candidate to host the “London” section, which will deal with life sciences and pharma cases, with Paris and Munich hosting the other sections of the Central Division. With five months to go before the UPC is expected to open its doors, might we expect an official announcement on the final arrangements for the Central Division in the in the next couple of months?

Amid all this progress, it was expected that Germany would complete its ratification of the UPC Agreement in December 2022, paving the way for an April launch date. However, problems with finalising the electronic case management system gave rise to a last-minute delay. It’s now expected that Germany will complete its ratification in February 2023, with the start of the ‘sunrise period’ (allowing early registration of opt-outs) scheduled for 1 March 2023 and the opening of the UPC on 1 June 2023.

Although predictions of launch dates have come and gone in the past, it really looks like 2023 will be the year of the UPC and the UP system. Now is the time to make decisions whether to leave existing patent portfolios within the UPC’s jurisdiction or to opt out, as well as whether to use the UPC for infringement/revocation actions, and to decide on whether to validate European patents as UPs once the possibility becomes available.

Conclusion

The future is always uncertain and there are many possibilities for what could happen in the world of science and technology. One question that remains is whether cryptocurrencies will regain popularity and whether plant-based diets will continue to be a trend. However, there is one development that is certain to bring significant change to the field of intellectual property: the implementation of the UPC. With the biggest change to European patent law in decades now just months away, the Mathys & Squire team will be there to provide advice at every step of the way.

Mathys & Squire is delighted to have been recognised in JUVE Patent’s UK rankings 2023. We are pleased to report that we have had a record number of Partners individually recommended in this year’s guide.

The 2023 edition brings together UK patent practices, solicitors and barristers, who, according to the in-depth research carried out by a team of journalists, have a leading reputation in the UK patent law market. As well as a practice-wide recommendation for the firm, four of our Partners have maintained their status as Recommended Individuals: Hazel Ford and Philippa Griffin (for ‘Pharma and biotechnology‘), Chris Hamer (for ‘Chemistry‘) and Jane Clark (for ‘Digital communication and computer technology‘ / ‘Mechanics, process and mechanical engineering‘), whilst James Wilding has been newly ranked in the 2023 guide in the fields of ‘Pharma and biotechnology’.

Partner Chris Hamer has also maintained his specialist Leading Individual ranking this year for his expertise in chemistry, one of only eight UK patent attorneys noted for their technical speciality.

To see the JUVE Patent UK 2023 rankings in full, please click here.

Mathys & Squire Partners Anna Gregson, Dani Kramer, Sean Leach and Martin MacLean have been featured in the 2023 edition of IAM Strategy 300 Global Leaders.

The guide showcases the top experts in intellectual property, whose approach is regarded as truly strategic in nature, drawing from the worlds of private practice, consulting and other service providers.

IAM says: Anna Gregson is a smart, considerate, and reliable business partner to universities, SMEs, and multinational organisations. She exhibits a thorough awareness of the market and understands the importance of intellectual property to a company’s overall business plan.

IAM says: With a thorough understanding of UK and EPO patent law, Dani Kramer is an extremely intelligent, well-informed, and dedicated to providing excellent client services. He bridges the gap between parties and his ability to tackle any problem is remarkable.

IAM says: Sean Leach is a superb patent attorney who stays current with technological advancements and has a broad but in-depth understanding of the field. He has outstanding communication skills, and his customer focus is second to none.

IAM says: Martin MacLean offers insightful guidance on intellectual property issues that is both practical and future-focused in its analysis of business and market trends. He takes a sophisticated and personalised approach to his work, and his strong portfolio management skills are an excellent asset.

We would like to thank each of our clients, contacts and peers who took the time to participate in the research. The full 2023 edition of the guide is available here.

Data and commentary provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in an article by Nutraceuticals World, providing an update on the growth of the medicinal gummies market.

A condensed version of the article is available below.

Nutraceuticals (i.e. supplements, functional foods and functional beverages) continue to grow in popularity amongst consumers, reflecting a more active approach to health and wellbeing awareness and management, and a shift toward a preventative healthcare paradigm. According to estimates from Research and Markets, the global nutraceutical market (covering supplements, as well as functional foods and beverages) is valued at US$330.6 billion for 2022 and is projected to reach US$441.7 billion by 2026, growing at a rate of 7.8% over the period.

Since starting out as a gelatinous confectionary, gummy sweets were first commandeered as a popular oral delivery vehicle for vitamin and mineral supplements for children in the mid-1990s. Unsurprisingly, those that enjoyed gummy vitamins as children have retained an affection for them into adulthood. Nevertheless, the gummy vitamin market has been dynamic in evolving and innovating to cater for broad consumer preferences to attract new gummy converts, particularly those who have ‘pill fatigue’. With that in mind, vitamin gummies can now be formulated to be plant-based, low sugar or sugar free, and free from artificial flavours or colourings.

What have been the stumbling blocks to medicinal gummies?

Given the popularity of gummies in the nutraceutical sector and prevailing issues with patient adherence, particularly with poor tasting paediatric oral medicaments and patients suffering chronic conditions, it might not be surprising that pharmaceutical companies would consider the viability of the gummy as a vehicle for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), in order to improve patient experience with certain oral medications.

Historically, there have been a number of reasons which have stalled the gummy’s use as a vehicle for APIs. The reliance on heat in traditional gummy manufacture can have unwanted effects on medicament stability compared with normal pharmaceutical tabletting processes. Moreover, gummies are not typically protected by films (e.g. in a blister pack), which can also contribute to stability and degradation issues. Indeed, in the nutraceutical sector, it is not uncommon to use excess amounts of a vitamin or supplement during gummy manufacture to counteract a level of degradation of the active during processing or storage. This is not an acceptable scenario in the pharmaceutical industry where dosage level is of paramount importance and APIs can be extremely expensive.

Another problem can relate to the solubility and/or chemical stability of APIs in the gummy formulation itself. The particular API may, for instance, undergo unwanted reactions with components of the gummy formulation or lack sufficient solubility within it, which can complicate the accurate dosing of API in individual gummies. A further issue relates to potential microbial contamination resulting from the use of traditional gummy manufacturing processes, which can fall short of required pharmaceutical standards.

However, it seems that more recent innovations in gummy formulation and manufacture have improved compatibility, such that medicinal gummies might be a realistic offering in the future.

Process innovation

Traditional gummy manufacture has relied on the use of a ‘starch mogul’ system which relies on a starch-based mould within which the gummy formulation is deposited, set and removed, before the starch is recycled. However, the use of starch/recycled starch moulds can pose difficulties in maintaining sufficient hygiene levels and ensuring that there is no cross-contamination, particularly for pharmaceutical grade products.

Manufacturers have looked to provide alternative starch-free systems to overcome those problems and one of the latest inventions includes enabling a gelatine gummy mixture to be deposited into silicone or metal-based moulds, or directly into blister packs, as a hygienic alternative to starch-moguls. This not only elevates hygiene levels up to pharmaceutical standards it also reduces gelatine setting times from approximately 24 hours to less than 15 minutes, thereby increasing output potential significantly.

Centre-filled gummies

Another development that may offer the greatest impact in bringing medicinal gummies to market is the centre-filled gummy, in which a gummy outer shell is provided with a liquid core. Different gelatine formulations have been developed that are increasingly compatible with low temperature processing. However, the centre-filled gummy allows separation of gummy formulation ingredients in the shell, which may be processed at high temperature, from those of a liquid core formulation which contain functional ingredients (such as APIs).

The separation can also prevent unwanted interactions between functional ingredients and those of the gummy formulation, whilst the gummy shell can act as a barrier to the functional core, thereby having a protective effect, helping to ensure adequate stability and shelf life to functional ingredients. The liquid core can also facilitate more accurate dosing of an active functional ingredient in an individual gummy, so that there can be certainty in dose levels to satisfy pharmaceutical requirements.

First investigational new drug (IND) application

An illustration that the tide may finally be turning toward medicinal gummies is also in the award of a first IND (140312) from the FDA in respect of Seattle Gummy Company’s allergy gummy medication. The company also claims to have a large pipeline of gummy drugs in development, with patent applications having been filed to gummy compositions with APIs, including antihistamines and analgesics (WO 2022/119959 A1, US2021386732 A1).

Summary

Given the continuing growth of gummies in the nutraceutical sector and the shift in consumer preferences, it seems that pharmaceutical companies would be missing a trick not to develop their own gummy product lines for their APIs, particularly with the threat of a patent cliff as original APIs come off patent.

The gummy sector is a particularly fast-growing branch of the nutraceutical sector and there appear to be signs that historic barriers to the use of gummies as an oral delivery vehicle for APIs are being removed by continued innovation in the sector. Given the popularity of gummies in the nutraceutical space, it seems only a matter of time before medicinal gummies are available, particularly to paediatric or geriatric patients, or those with chronic conditions, where traditional pill form medicaments may be poorly tolerated or there may be issues with non-adherence to treatment regimes.

In an appeal decision against the Receiving Section’s decision holding that an EP application was not to be treated as a divisional application, where the joint applicants were not identical to those of the parent EP application, the Board of Appeal confirmed that Rule 22(3) EPC is not applicable in case of universal succession.

Background

On the basis of an EP application filed by five joint applicants, a divisional application was filed in the name of four of the same five applicants (applicants 1, 3, 4 and 5) and a newly named applicant 2. A day after the divisional application was filed, the parent application was actively withdrawn. Due to the discrepancy in identity of applicant 2, the Receiving Section considered that the requirements of Rule 36(1) EPC were not met, and so decided that the application was not to be treated as a divisional application. Although the applicants filed proof by means of documents of merger showing that the original applicant 2 had merged into the newly named applicant before the filing date of the divisional application, the Receiving Section maintained that a divisional application could only be filed by the registered applicants of the parent application. Since the withdrawal of the parent application had already become effective, a transfer of rights of applicants of the parent application could no longer be registered. This decision of the Receiving Section was appealed by the applicants.

Reasons

In the reasons for the decision, the Board of Appeal acknowledged that the evidence on file showed that the newly named applicant is the universal successor of applicant 2. Regarding universal succession, they confirmed three prior Technical Board of Appeal decisions which held that universal succession is not a transfer of rights, such that universal succession can be considered as an exception to Rule 22(3) EPC (see T 15/01, T 6/05 and T 2357/12).

For a systematic assessment on the requirement of identity of applicants for divisional applications, the Board of Appeal established the meaning of “transfer” in the context of Rule 22 EPC as follows (point 4.4 of the reasons):

“Under Article 71 [EPC] a patent application is an object whose property can be transferred, or over which rights can be constituted and transferred. … Therefore, the transfer of a European patent application has the effect of making a patent application the property of another person.

The only provision relating to the conditions under which the transfer of a patent application may take place is Article 72 EPC, which states that “[a]n assignment of a European patent application shall be made in writing and shall require the signature of the parties to the contract”. Although Article 72 EPC governs formal requirements, the only reference made in the EPC to the transfer of a patent application is in the form of an assignment contract.” … Moreover, Rule 143(1)(w) EPC states that the European Patent Register must contain entries concerning the rights and transfer of such rights relating to an application or a European patent where the Implementing Regulations provide that they are to be recorded. Hence, it can be inferred from that provision that not all kind of transfers of rights need to be registered, but only those explicitly mentioned in the Implementing Regulations. In so far as Rules 22 to 24 EPC provide that transfers, licences and other rights in a patent application must be registered, the provisions of Rule 143(1) EPC can only be understood if the term “transfer” in Rule 22 EPC does not include all means of acquiring ownership of a patent application.”

An interpretation of Rule 22 EPC in view of its purpose, led the Board of Appeal to reach the same conclusion. In point 4.5 of the reasons, the Board held that:

“The intention of Rule 22 EPC is to ensure the informational role of the European Patent Register and to avoid any ambiguity as to who owns a patent application during proceedings before the EPO. … [These requirements] are justified when transferring a patent application by assignment, since only a specifically designated right is transferred to a third party and the former patent proprietor, i.e. the assignor, continues to exist. There are therefore two legal entities that still exist, and it is important to be able to determine, by consulting the Register, the extent of the rights whose ownership has been transferred and the identity of the owner.

However, in the case of universal succession, the entirety of the assets are transferred automatically as a result of the disappearance of the legal personality of the patent application’s owner. Consequently, there is no risk of confusion between two legal entities that could be considered owners of the patent application, nor regarding the extent of the rights transferred, since all assets remain united.”

The Board of Appeal concluded by stating explicitly that the notion of “transfer” in Rule 22 EPC should be interpreted as not covering universal succession, such that none of the requirements laid down in Rule 22 EPC is applicable to such cases. The Board thus set aside the decision of the Receiving Section to refuse to consider the application in suit as being a divisional application.

Comments and takeaways

Decision J 7/21 provides a welcome confirmation from a legal Board of Appeal that universal succession is considered an exception to the requirements under Rule 22(3) EPC. However, Rule 22(3) EPC is to be applied in cases of a transfer of rights where the former owner continues to exist.

Thus, where rights have passed by universal succession, recording a change in ownership of the parent application prior to filing of the divisional application is recommendable in case there is any question about the effectiveness of the change. In case of a transfer of rights by contract, e.g. by assignment, it seems to remain the case that the divisional application should be filed in the same name which is recorded against the parent application.

It should also be kept in mind in this context that transfers can only be registered for pending applications, i.e., where the withdrawal of an application is final, it can no longer be transferred (see, e.g. J 10/93). Particular care should therefore be taken when filing divisional applications where the parent application is intended to be withdrawn.

Commentary provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in an article by The Patent Lawyer, providing an update on the UPC and ‘patent trolls’.

An extended version of the press release is available below.

‘Patent trolls’, or ‘Non-practicing entities’ as they are generally now known, are companies that use patent rights to earn income from third parties, rather than producing their own goods or services under the patent rights. They often do this by litigating against businesses that they allege are infringing the patents owned.

Under the new laws of the Unified Patent Court, a company facing a patent infringement claim will have as little as two months to prepare their defence. Such a short period of time may be too little for a company to build a proper, robust defence in a complex case.

At present in national litigation, defendants normally have between four to six months to prepare their arguments, including usually an extensive search for prior art (i.e. evidence that the invention is already known or is obvious).

‘Patent trolls’ are expected to deliberately refrain from notifying the alleged patent infringer of the pending litigation until the very last minute, leaving them at a considerable disadvantage.

Chris Hamer, Partner at Mathys & Squire, says the narrow timeframe could make it significantly more difficult for defendants to prepare an effective defence.

Chris Hamer explains: “Some businesses may not even be aware that they are infringing a patent. Eight weeks is very little time for a business to review a summons, instruct legal counsel and come up with a successful defence. Patentees will be only too willing to exploit this advantage for them.”

Even if a patent troll is unsuccessful in enforcing their patent rights, they may only have to pay a small proportion of the other party’s legal costs in cases heard in the UPC. This could act as an incentive to pursue litigation.

Recoverable costs under the UPC are capped at €2m (for a case valued at more than €50m). The UPC also has the discretion to lower the cap if the amount threatens the economic viability of the company. In the UK (which is not under the remit of the UPC), recoverable costs are uncapped and the losing party could typically expect to pay 60-80% of the victor’s costs.

Andreas Wietzke, Partner at Mathys & Squire says: “For patent trolls, pursuing a case in the UPC could be a gamble worth making. If they are successful in blocking use of a patent, the injunction will apply to all selected jurisdictions within the UPC. Even if they lose the case, the potential for cost recovery is considerably lower than in countries such as the UK and US.”

“There has been concerns that the problem that the US has with patent trolls could spread to Europe. The UPC rules do seem to make the environment much more inviting to them.”

“If you are a corporate what you will need to do is set up internal systems so that as soon as a claim comes in you can respond quickly and prepare your case. If you don’t respond quickly you’ll not only be on the back foot, you could just lose by default.”

Data and commentary provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in articles by World IP Review and The Patent Lawyer, providing an update on the rapid growth in design applications.

An extended version of the press release is available below.

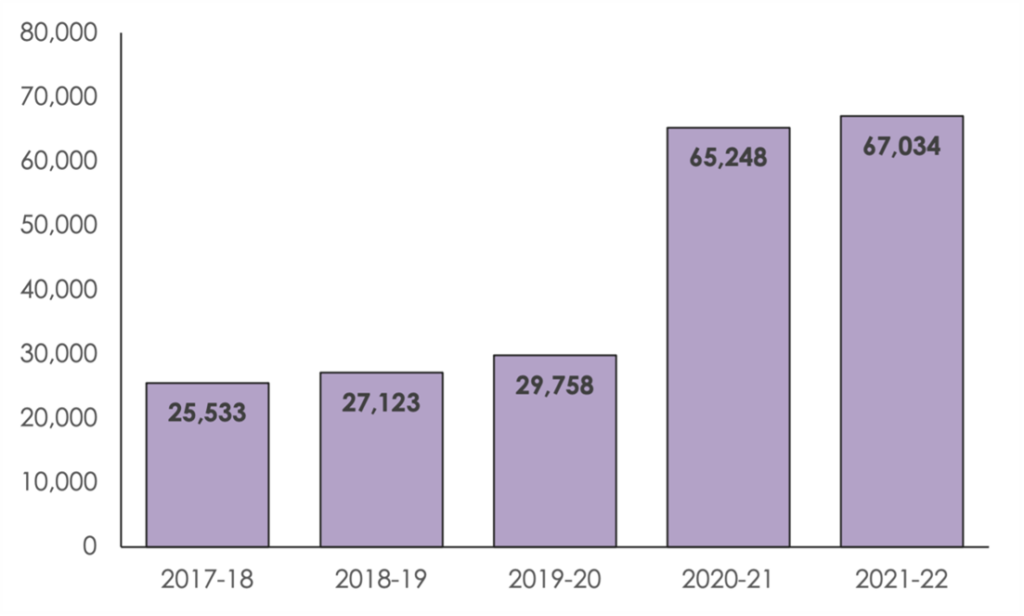

The number of applications made to the Intellectual Property Office to protect product design rights jumped to a record high 67,034 in the past year* up from 65,248 the previous year, says leading intellectual property law firm, Mathys & Squire.

In the past year, an average of 5,586 design applications were filed each month. In the year leading up to Brexit**, the average number of monthly applications was 2,480.

Brexit has prompted a rush for businesses to file new applications in both the UK and the EU to protect product designs. Since the end of the Brexit ‘transition period’ on January 1st 2021, the UK no longer falls under the scope of EU registered designs, which offer protection across all member countries of the EU. As a result, businesses now have to register a product design in both the UK and in the EU to obtain the protection that they would have once obtained via a single EU registered design application.

Design rights protect the appearance of a product such as its lines, contours, shape, colour, texture or the ornamentation of the product. Design rights can extend to include digital media products, such as computer game characters or graphic designs.

Mathys & Squire says design is a crucial aspect of product differentiation and it is becoming increasingly important for businesses to protect this often hotly-contested area of IP. Failure to take adequate protection could make it more difficult for them to scale up. Investors may decide that without protections for design, a business is not a safe investment prospect and withdraw financing.

Max Thoma, Managing Associate at Mathys & Squire says: “Design applications have seen a sharp spike in the last year and these figures are likely to remain high, as businesses will continue to have to register designs in both the UK and Europe.”

“Not having adequate protections in place for designs could have significant ramifications for businesses. Investors are increasingly keen to see that design rights and other IP is properly protected before they invest. That means failure to protect rights could see businesses miss out on crucial opportunities to grow.”

In addition to securing vital investment, registering designs is vital to ensure your IP is legally enforceable and competitors cannot enter the market with similar products.

Companies that have taken legal action over design rights include:

- The manufacturer of children’s luggage manufacturer, Trunki, and a discount competitor, Kiddee Case. The Supreme Court ruled that Kiddee Case did not infringe registered design rights, prompting a backlash from designers and entrepreneurs who argued that the ruling left the IP of British businesses vulnerable

- Apple accused Samsung of copying the shape of its iPhone series in the latter’s Galaxy range, which Apple claimed was an infringement of its registered designs. The UK High Court ruled in Samsung’s favour, ordering Apple to publish a notice on its website confirming there was no registered Community design infringement

*Year-end September 30th 2022

**2019-20

The Unified Patent Court (UPC) – which is expected to launch in April 2023 – will have jurisdiction not only for patent litigation, but also for litigation involving supplementary protection certificates (SPCs) issued for medicinal products and plant protection products. The types of patents for which the UPC will have jurisdiction are well-defined, but analysis by Mathys & Squire’s SPC team has identified some areas of uncertainty when it comes to SPCs.

These uncertainties relate particularly to SPCs which are in force at the launch date of the UPC, and potentially also to SPCs which were previously granted but which are no longer in force by that date. As such, these uncertainties are likely to be especially relevant during the early years of the UPC’s operation, and should be taken into account by SPC holders when deciding whether to opt their SPCs out of the UPC’s jurisdiction.

A brief summary of the problems is set out below. For those who are interested in the legal position, a more detailed analysis of the problematic provisions in the UPC Agreement and Rules can be accessed here.

The problems in brief

Due to a discrepancy in how the UPC Agreement (UPCA) defines the jurisdiction of the UPC with respect to patents vs. its jurisdiction with respect to SPCs, there is a lack of clarity over whether the UPC will have jurisdiction over SPCs which are in force on the date when the UPC officially opens its doors, i.e. where the underlying ‘basic patent’ has expired; and whether the UPC will have jurisdiction over SPCs which have ceased to have effect prior to that date (e.g. for retroactive assertion of those SPCs against historical infringements and/or for retroactive invalidation of those SPCs, subject to any applicable limitation periods).

In brief, European patents which have ‘lapsed’ prior to entry of the UPCA into force are excluded from the UPC’s jurisdiction (Article 3(c) UPCA). However, when it comes to SPCs, the wording of the UPCA seems to give the UPC jurisdiction over any SPC “issued for a product protected by a [European] patent” (Article 3(b) UPC) without explicit limitation as to the status of the SPC or its underlying patent. Thus, in essence, Article 3(b) might be interpreted as meaning that an SPC could fall under the UPC’s jurisdiction even if the patent forming the basis for that SPC is excluded from the UPC’s jurisdiction by operation of Article 3(c) – and potentially even if the SPC itself is no longer in force.

If the UPC does have jurisdiction over SPCs in such circumstances, there is also a potential discrepancy between the UPCA and the Rules of Procedure of the Unified Patent Court which renders it unclear whether, using the mechanism provided under the current Rules, such SPCs can be opted out of the UPC’s jurisdiction during the ‘sunrise period’ of three months before the UPCA enters into force or during the ‘transitional period’ of at least seven years which will follow (Articles 83(1) and 83(3) UPCA). In essence, it is unclear whether the Rules as currently constituted are appropriate to implement the opt-out procedure in respect of such SPCs.

In brief, this is because under Rule 5.2 the route to opt out an SPC is to opt out the underlying patent. Although Rule 5.1permits opt-outs to be registered for “expired” patents, it is not clear whether this rule can be applied to patents which expired prior to the entry of the UPCA into force. One interpretation suggests that Rule 5.1 can only apply to patents which would otherwise have been within the UPC’s jurisdiction before their expiry, i.e., patents which expire after the date on which the UPCA enters into force. Under this interpretation, a situation potentially then arises in which the UPC has jurisdiction via Article 3(b) over SPCs based on patents which expired prior to entry into force of the UPCA, but those SPCs cannot be opted out using the mechanism provided under the current rules.

In this context it may perhaps be relevant that Article 3(c) employs the term “lapsed” to refer to patents which are not in force, whereas Rule 5.1 employs the term “expired”. If these terms are intended to differ in scope, this could potentially offer a solution to the opt-out problem identified above – but with possible ramifications for the UPC’s jurisdiction over lapsed or expired patents, which are explored further in our detailed analysis.

As a further point of uncertainty, if the UPC does have jurisdiction over SPCs which are no longer in force when the UPCA enters into force, it is unclear how far back that jurisdiction might extend. This is due to a lack of harmonisation of limitation periods in the national laws of participating states, and the lack of a uniform statute of limitations in the UPC legal texts. This creates uncertainty surrounding the possibility of retroactive UPC litigation concerning such SPCs.

Summary and recommendations

As there are several possible ways of interpreting the provisions of the UPCA and Rules relating to SPCs, it seems quite possible that the UPC itself will be asked to decide on the correct interpretation if a suitable case is brought before it in its early years.

Although it is unclear whether expired SPCs and/or those which are in force when the UPCA enters into force will as a matter of fact fall under the UPC’s jurisdiction, the factors which we have identified above may play an important role when considering whether or not to seek to opt such SPCs out of the UPC’s jurisdiction.

SPC holders who are averse to the prospect of centralised revocation through the UPC may wish to take a precautionary approach, despite the uncertainties above, and attempt to lodge opt-outs in respect of the patents underlying such SPCs using the mechanism presently provided by the Rules, in order to opt the SPCs out of the UPC’s jurisdiction.

Download the full legal analysis here.

To discuss any of the issues raised above in more detail, please feel free to contact our experienced life sciences & chemistry team.

Following reports in October that the Administrative Council of the European Patent Office (EPO) had passed “a new package of rule changes intended to adapt the rules of the EPO to the digital age”, the EPO Administrative Council has now published official confirmation of this update.

The decision of the Administrative Council of 13 October 2022 amends a number of Rules under the Implementing Regulations of the European Patent Convention (EPC). These amendments confirm, amongst other changes, the abolition of the ‘10-day rule’ for notification of documents; instead, documents will be deemed to be delivered on the date that they bear.

A safeguard is provided by amended Rules 126 and 127 in the event that documents fail to reach the addressee, in which case the EPO bears the burden of proof to establish that documents were delivered and to establish the date on which they were delivered. If a document is received more than seven days after the date shown on the document, the period for response will be extended at its end by the number of days exceeding seven. This brings EPO practice more closely into alignment with similar provisions under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) for international patent applications.

The EPO’s decision confirms that this change will enter into force on 1 November 2023 and apply to documents notified by the EPO on or after the same date.

Other rule changes approved by the Administrative Council, which come into force on 1 February 2023, relate to the requirements for the formatting of the application documents. At present, the Rules contain prescriptive requirements relating to (for instance) page margins, the presentation of drawings, and text size and spacing. In recent years, many of these rules have not been strictly enforced, especially with the decline of paper-based filing. The amended rules no longer contain these detailed provisions, but instead grant the EPO President a wide discretionary power to determine suitable requirements. This seems to be intended to allow greater flexibility to adapt the EPO’s practices for electronically-filed documents.

A further rule change as of 1 February 2023 relates to the provision of search results. At present, when a European search report is drawn up, the EPO is required to transmit this to the applicant together with copies of any cited documents. An amendment to Rule 65 now removes the requirement for the EPO to ‘transmit’ copies of the cited documents, and instead specifies that the EPO should “make available” copies of those documents. It remains to be seen how this will be implemented, but one possibility mentioned in the EPO’s detailed proposal document is that the EPO will make citations available in a digital repository rather than sending them directly to applicants. Among other things, this rule change is intended to allow for easier citation of ‘non-traditional’ references such as videos and other multimedia presentations.

The full details of the changes, including their context within the EPO’s Strategic Plan 2023, are now available through the published proposal document.

Semiconductor shortage continues to be an issue worldwide for the tech sector. Even the introduction of economic packages, such as the US CHIPS and Science Act, which aims to invest $280 billion to bolster their national semiconductor capacity, have done little to boost confidence in global semiconductor reserves. Now, new policies coming out of Washington could have major implications on global semiconductor trade.

Last month, the US government released a regulatory filing that went relatively unnoticed, particularly when considering its context in terms of the global ramifications that could proceed. The US government has announced the implementation of additional export controls on their semiconductor manufacturing items, implementing trade barriers to 28 entities, all located in China.

Whilst finished semiconductors are seldom made in the US itself, manufacturing entities within China rely on US imports of resources for their chip production. This is yet another blow in the semiconductor trade war ongoing between these two global tech giants, one which may be seen as a US attempt to hinder China’s technological ambitions, as highlighted in their latest five-year plan.

As trade negotiations continue, Europe has been significantly impacted by these global changes to semiconductor trade. In the immediate fallout of these export controls, there is considerable uncertainty for European chip firms when considering trade with their US and Chinese clients. There is also great concern amongst private companies across Europe, as to the unintended consequences the US government’s actions will have on international supply chains, and more pressingly, how the Chinese government will respond to these serious trade regulations.

The implications on trade within the EU can already be seen. As the US went ahead with these restrictions without any public consultation or conference with international allies, nations have been caught off guard, and confidence in future chip supplies has slipped. It is vital governments and their representatives communicate that the new trade restrictions will have no impact on European technology competitiveness, whilst also ensuring that the US-EU Trade and Technology Council (TTC) keeps its legitimacy as a body responsible for the discussion of transatlantic trade controls.

Where the US CHIPS act saw massive amounts of investment funnelled into semiconductor research and development, a more inclusive STEM workforce, and bolstered semiconductor capacity, the European CHIPS act is still a moot point with no concrete legislation. Now more than ever, a regional European semiconductor investment policy is needed to combat some of this global uncertainty. The semiconductor industry has now become a complex economic environment, one which Europe needs to ensure it can navigate if it wants to maintain its standing within the worldwide tech sector.

Although a cemented legislative CHIPS act for Europe appears to be some way off, it is clear that Europe is attempting to develop a more independent tech manufacturing sector. In April of this year, the European Commission put forward the possibility of a European CHIPS act equivalent, with aims to boost Europe’s share of global chip manufacturing from 10% to 20% in the coming years. This act aims to boost investment for technological capability and capacity, as well as to provide some levels of strategic autonomy for Europe moving forward. If this investment package becomes a solid reality, European governments can feel more comfortable when considering the trade regulative activities of the likes of China and the US.