The European Patent Office (EPO) has published a draft version of the amended Guidelines for Examination which will enter into force on 1 March 2023. A summary of the main changes is included below.

Unified Patent Court

With the Unified Patent Court (UPC) sunrise period also due to begin on 1 March 2023, the Guidelines have been amended to extend existing provisions relating to national proceedings to include proceedings before the UPC. For example, where an infringement action in respect of a European patent is pending before a national court of a contracting state or the UPC, a party to the opposition proceedings may request accelerated processing (E-VIII, 5).

In addition, Guidelines C-IV, 7.2 introduce guidance on national prior rights in view of their importance for applicants in proceedings before the UPC. This section reflects the recently introduced practice under which the examiner expands the top-up search scope at the grant stage to include national applications and patents of the contracting states in so far as they are present in the EPO’s databases. The division informs the applicant about the outcome of the top-up search for national prior rights and any documents that are considered prima facie relevant for the application are communicated to the applicant.

Oral proceedings by videoconference

In accordance with the OJ EPO Decision 2022, A103, the wording of the Guidelines has been updated to recite that oral proceedings are held by videoconference, or, in exceptional circumstances, where there are serious reasons against holding the oral proceedings by videoconference, they may be held on the premises of the EPO (E-III, 1.2).

The guidance has also been updated to reflect the procedure for when technical problems occur such that the oral proceedings held by videoconference cannot be conducted openly and fairly, for example due to a total or partial breakdown in communication.

If the sound or image transmission of any of the participants taking part in the oral proceedings is lost, the chair will stop the proceedings until the transmission is re-established. If a participant is disconnected for more than a few minutes, a member of the division will contact that party to see if they are having technical problems. Any relevant information will be shared with all parties. If a party reconnects after a temporary connection failure, the chair will make sure that no information has been missed. Some arguments might have to be repeated.

If, despite all efforts of the participants, technical problems prevent the oral proceedings by videoconference from being conducted in accordance with the parties’ rights under Art. 113 and Art. 116, the videoconference will be terminated. A new summons to oral proceedings will be issued. As a rule, new oral proceedings will be held by videoconference unless there are serious reasons for not doing so (E-III, 8.2.3).

This may provide peace of mind to all parties involved in videoconference oral proceedings.

Summons to oral proceedings as the first action in examination of a divisional application

Part C-III, 5 of the Guidelines has also been updated to include a list of exceptional cases whereby the examining division may exceptionally issue a summons to oral proceedings as the first action in examination of a divisional application. Such exceptional circumstances include if:

- the parent application was refused or withdrawn and there is no prospect of a grant for the divisional application, even taking into account the applicant’s reply to the search opinion;

- the content of the claims on file is substantially the same as or broader than the subject matter of claims which were examined for the refused or withdrawn parent application, or which served as a basis for the search of the divisional application, and

- one or more of the objections which are crucial to the outcome of the examination procedure, and which were raised in the search opinion established for the divisional application, in the refusal of the parent or in a communication issued for the withdrawn parent still apply.

Correction of erroneously filed application documents or parts

Section A-II, 6 of the new Guidelines has been introduced to reflect new Rule 56(a) of the Implementing Regulations which entered into force on 1 November 2022 (OJ EPO 2022, A3). This new provision relates to procedures by which an applicant can correct “erroneously filed” parts of a European patent application. This brings the European Patent Court (EPC) into conformity with PCT Rule 20.5bis which also allows correction of erroneously filed elements of an international application. Previously, the EPC only provided provisions by which ‘missing parts’ could be filed (Rule 56).

The application is examined on filing to check that it is entitled to a date of filing. If, during this check, the EPO establishes that the description, claims or drawings (or parts of them) appear to have been erroneously filed, it will invite the applicant to file the correct documents within a time limit of two months of a communication under Rules 56(1) and 56a(1).

Alternatively, if, within two months of the original date of filing, applicants notice that they filed erroneous application documents or parts, they should, of their own motion, file correct application documents or parts as soon as possible under Rule 56a(3). The guidelines set out that whether documents were erroneously filed depends only on the applicant’s statement as to what was intended. No further evidence is required by the EPO.

As with missing parts, if, after the filing date, the applicant corrects erroneously filed application documents, then the date of filing does not change, provided that all of the following criteria are satisfied:

- the correct application documents (or parts) are filed within the applicable time limit (the applicable time limit being the later of (i) two months from the original filing date, or (ii) two months from a communication under Rules 56(1) and 56a(1) to file the correct documents);

- the application claims priority on the date on which the requirements of Rule 40(1) were fulfilled;

- the applicant requests that the correct application documents be based on the claimed priority in order to avoid a change in the date of filing, and does so within the applicable time limit;

- the correct application documents are completely contained in the priority application;

- the applicant files a copy of the priority application within the applicable time limit unless such a copy is already available to the EPO under Rule 53(2);

- where the priority application is not in an official language of the EPO, the applicant files a translation into one of those languages within the applicable time limit unless such a translation is already available to the EPO under Rule 53(3); and

- the applicant indicates where in the priority application and, if applicable, where in its translation, the correct application documents are completely contained, and does so within the applicable time limit.

It is also worth noting that erroneously filed application documents remain in the file, even if they are considered not to form part of the application as filed. As such, following publication of the application, the erroneous application documents or parts are open to file inspection.

Erroneously filed sequence listings may also be corrected under Rule 56a (A-IV, 5.2).

Sequence listings

The updated Guidelines also confirm the EPO’s position that an ST.26 sequence listing must be filed for all divisional applications, regardless of whether the parent application was filed prior to ST.26 coming into force.

The Guidelines state that, since the content of the disclosure of the invention is the responsibility of the applicants, any sequence listing which is to form part of the description must be filed by the applicant. The sequence listing of the earlier application is, thus, not automatically added to the dossier of the divisional application if:

- the applicant files an ST.26-compliant sequence listing as part of the divisional application’s description; or

- the sequence listing available in the earlier application does not comply with WIPO Standard ST.26 (A-IV, 5.4).

This comes despite concerns that the requirement for all divisional sequence listings to be in ST.26 format places an unnecessary burden on users, as well as concerns that the requirement may force applicants to add matter in cases where the ST.25 sequence listing contained less information than the ST.26 sequence listing.

Contracting states to the EPC

Montenegro has also been added to the list of EPC contracting states following the effect of its ratification on 1 October 2022 (General, 6). As such, Bosnia and Herzegovina is now the only remaining extension state (A-III, 12).

Consultation

The EPO has invited comments on the updated Guidelines by way of a consultation running until 4 April 2023. More information on the consultation can be found here.

Following the Decision of the Administrative Council of 14 December 2022, the European Patent Office (EPO) has announced a general increase in official fees by 4-6% from 1 April 2023 – just a year after its last fee increase in April 2022. Full breakdown of the increases is available on the EPO website.

The fees with the largest increase include excess pages, excess claims per claim 16-50, and examination, whilst the filing fee for an application in character-coded format is the only one to decrease in price.

With the increases in mind, it might be sensible to pay certain fees early, before the rates go up. For example, requesting examination and paying renewal fees can be performed several months ahead of the official deadline so applicants may find it worthwhile to review their patent portfolios and check if any fee payments can be made ahead of the 1 April 2023.

For more information about the fee increases and how they may affect you, as well as to discuss any potential cost savings, please get in touch with your usual Mathys & Squire attorney, or send us an enquiry.

Data and commentary provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in articles by The Times, The Patent Lawyer, UK Tech News, L’Entrepreneur, Business & Innovation Magazine , Facts Chronicle, World Intellectual Property Review and The Business Magazine providing an update on the rapid growth in semiconductor patents applications.

An extended version of the press release is available below.

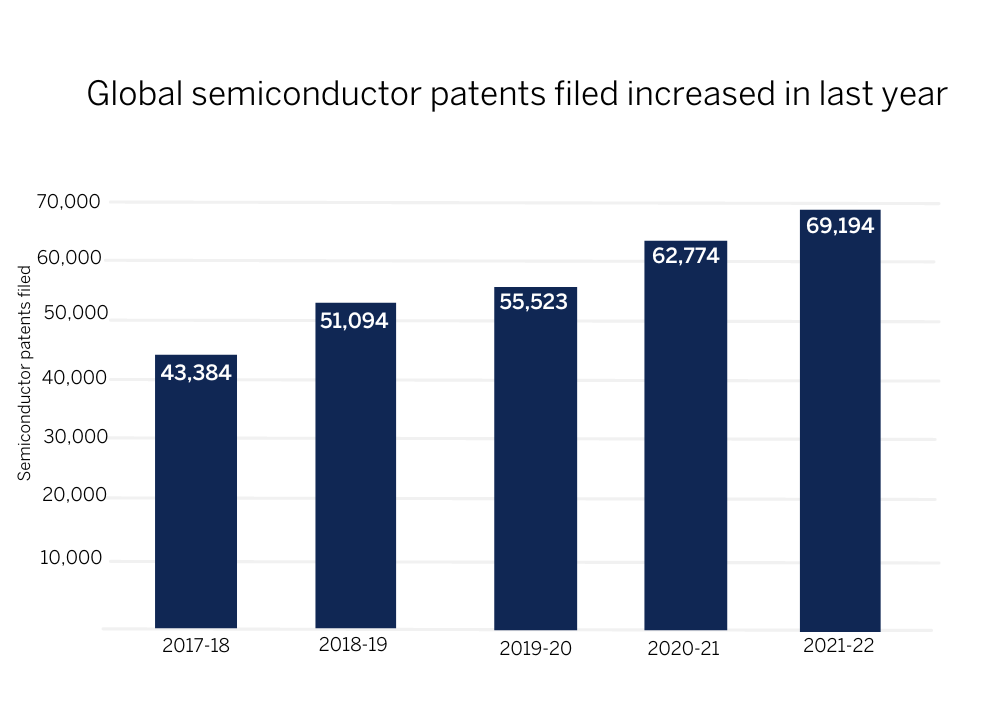

There have been a record 69,190 global patents for semiconductors filed in the past year*, up 59% from 43,380 five years ago and 9% more than the 62,770 filed in 2020/21, shows new research by Mathys & Squire, the leading intellectual property law firm.

R&D in the semiconductor industry has underpinned the growth in technology and the intense competition within the sector has ensured that innovation continues at a fierce pace.

The global semiconductor industry is forecast to be worth $1 trillion by the end of this decade – up from $590 billion in 2021**.

US giants Intel and AMD have been locked in a years-long rivalry to dominate market share within computers by designing ever faster, higher-capacity processors. Meanwhile companies such as Cambridge-based Arm have targeted semiconductor design for mobile devices. Such intense commercial rivalries often lead to the active filing and enforcement of patents.

By 2030, the automotive sector is predicted to make-up 15% of global demand for semiconductors, up from 8% in 2021***. Another key area of growth is the ‘Internet of Things’, including everything from wearable tech to smart homes and even smart cities.

As rising geopolitical tensions have led to trade barriers for key technologies, Governments have taken steps to secure their access to semiconductors.

Last year, the US Congress passed the CHIPS and Science Act, which allocated $280 billion to promote the research and manufacture of semiconductors in the United States. The European Union is currently considering a European Chips Act in order to boost Europe’s semiconductor industry.

As the growth of domestic semiconductor industries becomes a feature of more countries’ industrial policies, we can expect new patent filings to continue as businesses seek to protect and monetise their technological advances.

China filed 55% of global semiconductor patents in the past year

In 2021-22, 55% of semiconductor patents (37,865) were Chinese in origin. China has placed a major focus on boosting domestic semiconductor production in order to reduce dependence on western technologies.

The largest individual filer in 2021/22 was semiconductor giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) Limited, which was responsible for 4,793 patents – 7% of all patents worldwide.

18,223 of the patents filed in the last year (26% of the total) were filed in the United States. The top US filer was California-based Applied Materials Inc, with 209 patents, followed by SanDisk (50 patents) and IBM (49 patents).

In contrast, the UK accounted for only 179 patents, just 0.26% of the global total.

Edd Cavanna, Managing Associate at Mathys & Squire, says: “Governments are increasingly concerned about the fragility of global supply chains and are taking steps to promote semiconductor research and production domestically. New technologies which emerge from this global technology race will be protected by patents which are likely to be fiercely enforced.”

“Global powers such as the US, China and the EU are competing to be leaders in semiconductor technology. That says it all regarding their importance for the future of the economy.”

“However, the UK lags behind other parts of the world in developing semiconductor technology. The UK Government may wish to consider whether current funding structures provide enough support to research and development in this vital field.”

*Year end September 30 2022, Source: World Intellectual Property Organization

**Source: McKinsey

***Source: McKinsey

Germany has finalised its approval of the Unified Patent Court (UPC), opening the UPC’s case management system and kicking off the court’s sunrise period from 1 March. The start date for the UPC is now 1 June 2023.

Germany’s move brings closer the biggest development in European IP law since the creation of the European Patent Office in 1977. The UPC has been an aspiration for the EU for half a century with several attempts at introducing a single European patent court blocked over the years before a breakthrough was finally made in 2013. Following a number of other challenges over the last few years, the UPC is on the precipice of finally coming into force.

The UPC – presiding exclusive jurisdiction over European patent litigation – means businesses will only need to make one legal claim to enforce their patents across Europe. Costs will reduce so much that they will be comparable to making a claim in only one country previously. The new process will also make it more convenient to enforce patents across Europe for UK and EU businesses.

The start of the UPC’s sunrise period means businesses have three months to decide whether to opt their patents out of the UPC before full commencement. Businesses that anticipate having to defend their patents may wish to exercise their opt-out. Opting out would prevent competitors from ‘knocking-out’ their patent across Europe in a single judgement, making it easier to defend their patents from challenges.

Andreas Wietzke, Partner at Mathys & Squire says, “UK businesses need to seriously consider whether it is best for them to opt out of the UPC now that the Sunrise Period has begun.”

“The UPC has long been a dream for the EU and provides many benefits for those wanting to enforce their patents across the single market. But for existing patent holders, it could mean an increased risk that their IP will be challenged, with a single judgement able to ‘knock-out’ patents that had applied in several jurisdictions across Europe.”

“The ease at which patents could be challenged may incentivise competitors to gamble and discover if they can disrupt their competition now that it is more convenient and cheaper to do so. UK businesses have three months to decide how to best protect their IP before the UPC goes into full effect.”

The UPC was first agreed in 2013 but was held up for years by the domestic ratification processes of member states. Germany’s final approval of the system means that it is set to become fully operational in three months once the sunrise period elapses.

French luxury brand Hermès has prevailed in a significant US court case after a year-long trade mark battle. Mason Rothchild’s ‘MetaBirkin’ non-fungible tokens (NFTs) were found to violate Hermès’ trade marks for its renowned Birkin bag, making Rothschild liable for trade mark infringement, trade mark dilution, and cybersquatting.

The trial is one of its kind, in which we see the interplay of intellectual property law, fashion and technology. It has also set an important precedent on what may be considered artistic expression and how NFTs are viewed in the eyes of intellectual property law.

The Birkin bag

Introduced in 1984 and named after the actress Jane Birkin, the Hermès Birkin bag quickly became iconic and is one of the most sought-after items in the fashion world. It is undeniable that the Birkin bag, manufactured in France with precise and distinctive craftsmanship, has evolved into a symbol of status and luxury and is known for its exclusivity. For the opportunity to own a Birkinbag, customers must have a purchase history with the brand and may often wait months or years to be offered one.

Hermès owns trade mark rights in the Hermès and Birkin marks and trade dress rights in the Birkin bag design.

The Hermès v Rothschild case

In 2021, Rothschild began selling MetaBirkin NFTs which portray reworked Birkin bags made of fur with vibrant colours and designs, rather than the conventional leather of the genuine Hermès bag and priced equivalently to a real Birkin bag.

Rothschild claimed that his MetaBirkin NFT project was an “artistic experiment” which provided commentary on Hermès’ manufacturing and examined society’s fixation on status symbols and luxury bags.

Upon discovery of MetaBirkin, the luxury brand filed a lawsuit in January 2022.

Hermès contended that Rothschild had capitalised on its goodwill; the NFTs were only bought because of the Birkin name which led consumers to assume the goods were formally affiliated with the brand and endorsed by Hermès themselves. Hermès contends that Rothschild not only used its Birkin mark without authorisation but also benefited openly from doing so by selling and reselling NFTs.

Rothschild relied on a fair use defence as per the First Amendment of the U.S. constitution and claimed that the NFTs are an act of artistic expression rather than trying to pass the artwork off as being associated with Hermès, drawing parallels with Andy Warhol’s paintings of Campbell’s soup cans.

Rothschild also relied on the ‘Rogers’ legal test. The criteria, which was first established in the Rogers v Grimaldi case from 1989, permits artists to use a trade mark without obtaining permission so long as it satisfies a basic requirement of artistic relevance and does not deliberately mislead consumers.

Although Hermès does not yet sell NFTs, unlike some of its peers in the luxury fashion world, the company’s global general counsel Nicolas Martin has commented there are plans to break into the metaverse, but this has been hindered by Rothschild as there will always be a reference to MetaBirkin.

The jury ruled in favour of Hermès, finding that Rothschild’s unauthorised versions of the Birkin bag constituted trade mark infringement, trade mark dilution, and cybersquatting as Rothschild used the MetaBirkins.com domain name, which the court determined was confusingly similar to that already of the luxury fashion house, awarding Hermès $133,000 in damages.

The jury also found that because of Rothschild’s unauthorised use of the bag as an NFT, this was not an artistic expression as it was explicitly misleading to consumers and therefore not a protected form of speech under the First Amendment of the U.S. constitution. The jury found that the ‘MetaBirkin’ was more akin to consumer goods, which are subject to trade mark regulations, than free speech-protected works of art, and that Rothschild did this to profit from Hermès’ goodwill.

Implications

This trial marks a win for IP protection for luxury brands in general, but perhaps the law lags behind innovation. While this case is the first to explore what constitutes “artistic expression” in the context of NFTs and IP, it is very fact specific and there is still much to consider regarding the legal issues presented by this new digital form of expression. It is the first of many judgements we can expect to see as the technology and ecosystem around NFTs continue to evolve and courts are required to provide more guidance on what constitutes infringement in the trade mark world and metaverse.

There is also some guidance on how intellectual property law is applied to digital assets and NFTs for artists and those working in this space, particularly in light of ongoing legal disputes such as Nike v StockX.

Questions do remain unanswered, and it may not be all over for Rothschild as there could be a possible appeal.

A trade mark dispute between Jack Daniels and VIP Products, around a dog chew toy resembling the Jack Daniels bottle, will be heard by the US Supreme Court. Although this case involves parody and trade mark law rather than NFTs, it could serve as a precedent for the conflict between freedom of expression and commerce, which will contribute to expanding the initial parameters set here in Hermès v Rothschild and help continue to define the scope of trade mark law in the digital age.

Mathys & Squire is delighted to announce that our trade mark team has been recommended in the latest World Trademark Review (WTR) 1000 guide. Praised for “having a specialised knowledge of trade marks”, as well as “adopting a client-oriented approach and delivering high quality results”, Gary Johnston and Margaret Arnott are also named as Recommended Individuals.

The WTR 1000 directory illustrates the depth of expertise available to clients, serving as the definitive tool for those seeking outstanding trade mark services worldwide. Now in its thirteenth year, the guide researchers have spent four months analysing the trade mark legal services market through an extensive interview process. Mathys & Squire has been recommended for its work in the trade mark field, specifically in the ‘prosecution and strategy’ category. Our “team of experts share their clients’ ambition, passion and entrepreneurial spirit, going above and beyond what is expected when it comes to service delivery.”

Alongside our firm ranking, Partners Margaret (recommended in the categories of ‘Enforcement & Litigation’ and ‘Prosecution & Strategy’) and Gary (recommended in the category of ‘Prosecution & Strategy’) have received the following feedback:

“Margaret is practically a trade mark encyclopaedia. She can answer any question that a client may have and knows how to get great results. Margaret is also very pragmatic and will always provide the full picture prior to assisting in the decision making process.”

“Gary is an experienced, commercial and pragmatic lawyer who is highly knowledgeable about IP.”

We would like to thank each of our clients, contacts and peers who took the time to participate in the research. For more information and to see the full WTR 1000 rankings, please click here.

On 24 January 2023, the Science and Security Board (SASB) of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists announced that the hands of the Doomsday Clock have been moved forward. The clock, which is a universally recognised indicator of the world’s vulnerability to global catastrophe caused by manmade technologies, now stands at 90 seconds to midnight. The primary reason for moving the Doomsday Clock forward was said to be the war in Ukraine, notably the increased risk of nuclear war.

However, the SASB also consider the war to undermine global efforts to combat climate change. In particular, the SASB state that “countries dependent on Russian oil and gas have sought to diversify their supplies and suppliers, leading to expanded investment in natural gas exactly when such investment should have been shrinking.” The announcement is thus another reminder of the importance of investing in research and development of green energy if we are to mitigate a global climate catastrophe.

One such form of green energy is solar energy, however, sunlight is an intermittent energy source meaning that it is not always reliable. Therefore, we need an efficient means of converting solar energy into another form of energy. This is where artificial photosynthesis may be useful. Plants can survive for periods without sunlight because during the day sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide are converted into chemical energy in the form of sugar.

The ultimate goal of artificial photosynthesis is to mimic this reaction, but on a larger scale and in a more controlled environment. It is hoped that the products produced by artificial photosynthesis could be used in the production of fuel (e.g. for cars), but also for supporting the growth of crops (e.g. using the acetate produced during artificial photosynthesis) in areas of extreme temperatures, drought, floods, and perhaps, even in space.

Historically, artificial photosynthesis involves a photoelectrochemical (PEC) cell comprising a system that activates a photosensitive substance, such as a semiconductor, submerged in a liquid solution to trigger the chemical reaction. More recently, chemical engineers at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland developed a prototype of an ‘artificial leaf’ which enables water to be harvested directly from humid air using a novel gas diffusion electrode.

The artificial leaf comprises a small transparent wafer of glass fibres that is made by blending and compressing glass wool fibres into a wafer. The wafer is then coated with a thin porous transparent film of a conductor (fluorine-doped tin oxide) which functions as a gas-electrode. A second coating comprising a sunlight absorbing semiconductor material (i.e. copper(i) thiocyanate) is then applied.

Importantly, the novel gas electrodes have two key characteristics. Firstly, unlike previous gas diffusion electrodes, which are typically made from opaque carbon-based materials and are used in fuel cells which do not require sunlight (e.g. zinc-air batteries and nickel-metal hydride batteries) the electrodes used in the artificial leaf are transparent to maximise sunlight exposure of the semiconductor coating. Secondly, the electrodes are porous to maximise the contact with the water in the air. Specifically, unlike PEC cells which comprise a flat surface onto which the semiconductor material is applied, the artificial leaf comprises a three-dimensional structure that vastly increases the surface area to maximise contact with water in the air. The resulting artificial leaf is able to absorb light and convert gas-phase water into hydrogen.

Although, as with other forms of artificial photosynthesis, the solar to hydrogen conversion efficiency of the artificial leaf is relatively low, the prototype offers an important proof of principle that PEC cells can be adapted to use gas-phase water. It is hoped that following optimisation of, for example, the pore size, thickness of the coatings, and the semiconductor and catalyst used, the artificial leaf may be used in solar cells in both arid and humid environments.

Some sources suggest that the artificial photosynthesis market size will grow from 62 million USD in 2022 to 185 million USD in 2030. Currently, the market appears to be largely driven by government funding and grants for research and development (R&D), however, private companies are also increasingly investing in their own R&D. It is perhaps unsurprising that there has been an upwards trend in the number of patent filings relating to this field. Whilst there is still a way to go before the technology is ready for mass consumption, there are encouraging signs that we are moving ever closer to a truly reliable green energy source.

Peter Drucker and Edwards Deming are most often cited as saying that “you can’t manage/improve what you don’t measure.” How do you know which intellectual property (IP) rights to devote more resources to, if you do not know what value it is bringing to the business?

Unlike tangible assets such as cars, houses and machinery, intangible assets (IA) add value through contributions to creating revenue. Examples of IAs include intellectual assets, intellectual capital, and intellectual property. It is not only registered IP rights, such as patents, trade marks, and designs that add value, but the people, contracts, databases, trade secrets, know-how and business efficiencies as well. All of these can be individually valued, or as a combination within a product or service.

Such assets are created by virtue of our skills, experience, and innovative ability to solve problems, hence the intellectual and intangible labels. Businesses and organisations need to understand what intangible assets they possess, identify where these add value to the business or organisation, and finally, put a value on these assets. This process is what we call IA/IP valuation.

Usually, most valuation exercises take place following a trigger event which necessitates it, like a sale, licence agreement, investment round, calculating loss of earnings through infringement of IP, transfer pricing arrangements or even insolvency.

However, there are many benefits to getting ahead of trigger events and starting early. It is advised to get a formal valuation done right after an IP audit. The best practice would also entail updating it regularly as you generate new IAs and relinquish others – it is all about actively managing your portfolio and knowing its value, which can often open up unthought avenues for commercial gain.

Despite its significance and benefits, IP valuation is still shrouded in mystery. The common methods of its calculation fall into three main categories and the differentiating circumstances are the deciding factor as to which one is used. These are the cost method, market method and income method, all conceptually easy to understand, and not just based upon accounting and financial considerations alone, but also a market view of the company, its position within the market and opportunities for growth, including an analysis of risk, a consideration which can greatly affect value.

The cost method looks at the cost to reproduce either the exact same asset, a replication, or a similar asset with the same utility. The premise of value here is that no one would want to pay more for an asset which they could generate internally from scratch. Other considerations include how the asset has aged, or become obsolete, which reduces value. A drawback is that this does not actually give the company an indication of value, but rather opportunity cost and therefore ignores the value which owning the asset contributes to future income.

The market method for IP valuation works the same way as it does for tangible asset valuation. It involves investigating the market prices for a similar house on the same street for example, or the same age and make of a car. Just like a house will be adjusted for having an extension or larger garden, a patent value must be adjusted for countries where it is granted, field of use, claims cover and other factors. This method relies heavily on a liquid market with a lot of exact transactions, which is hard to find in an intangible asset class. Again, it only looks at the current market value, not considering the future capability to generate income.

Considering the drawbacks and the limited usefulness of the above methods, the most common measure of value for IAs and IP is the income method, which looks at financial modelling and forecasts for the business using the IP asset. The cash flows are calculated and then discounted back to today’s value using the discounted cash flow method. This method gives a more realistic valuation in terms of earning capacity and capabilities for the IP over time.

The full process of conducting an IP valuation exercise is supported by a team of people with expertise in financial modelling, market and risk analysis, sector specific knowledge, as well as IP from a commercial and legal perspective. Expert involvement allows for a comprehensive and reliable analysis of the assets and market in question, resulting in an accurate valuation.

Our Mathys & Squire Consulting team is well equipped to answer any further questions you may have.

A recent judgement has been handed down relating to ownership of employee inventions in an academic context which is of relevance to all universities in the UK. The decision of Oxford University Innovation Limited (OUI) vs Oxford Nanoimaging Limited (ONI) was handed down at the end of December 2022, relating to the fairness of revenue split and ownership of invention between OUI and ONI; the judge finding in favour of OUI.

The key issue was whether, or to what extent, OUI were entitled to the rights of inventions made by inventor Mr Jing which was made more complicated by Mr Jing having been a research intern and subsequently a DPhil student at the University of Oxford.

OUI are a wholly owned subsidiary of the University of Oxford and manage the university’s technology transfer and consulting activities. Formed in 1987, OUI has managed the creation of 196 spinout companies and still has shares in 160 of them. ONI is one such spinout; they are a biotech company that focus on making desktop-sized super-resolution microscopes. They were formed in early 2016 and supported by OUI in return for equity to commercialise the research work of Mr Jing (then a DPhil student), Professor Achillefs Kapanidis and Dr Crawford.

Under its statues (specifically Statute XVI, Part B) the University of Oxford owns any intellectual property (IP) created by employees, students or anyone using their facilities, with the IP then being assigned to OUI. In this case, the IP was licenced to ONI in return for 50% equity; OUI bringing the case to court as it claimed around £700,000 in unpaid royalties as a result of their equity share, with ONI refuting that OUI had the rights to them.

One issue the case revolved around was whether Mr Jing was considered to be a ‘consumer’ and thus would be offered protection under the Consumer Rights Act of 2015. The judge commented that there was little case law to guide his decision, instead relying on two guidance notes published by the Competition and Markets Authority in 2015. These describe how undergraduate students are generally to be considered consumers for the maintenance of student confidence in the Higher Education (HE) sector, even if they seek to pursue a career related to their studies in the future. From this starting point and equating features of their respective courses (requirement for certain careers, payments to a HE body etc.), the judge found that in general a DPhil student should also be treated as a consumer. The judge found no reasons specific to Mr Jing in this case that he should not be treated as a consumer.

Another issue the court sought to answer, having concluded Mr Jing to be a consumer, was whether the university’s IP Statute were ‘unfair’ within the meaning of the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations. The judge commented that he felt Mr Jing was defending the case to improve the position of students within the university, rather than doing so for personal benefit. ONI defended on grounds relating to fairness, wording, and implementation of the university’s IP policy.

Despite finding the IP policy to be poorly and too broadly worded, the judge ruled that the policy had been implemented fairly, especially in light of an IP Advisory Group meeting in 2017 that decided to amend the policy to improve its accuracy and ease of understanding and application. For comparison, the judge discusses other UK and US institutions and their share of equity in related inventions. In the US these range from 5% at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to 100% at California Institute of Technology, and in the UK from 20% at the University of Cambridge to 67% at the University of Bath. These are however just headline figures; Cambridge for instance stating their share to be negotiable whilst there is nothing said of non-equity benefits received (such as research funding) due to promotion by an organisation such as OUI.

This case once again raises the question of ownership of invention. Although OUI did not challenge that Mr Jing alone devised the licensed IP, his position as an intern for seven months, prior to commencing his DPhil studies, and the unusual way in which he was employed (being contracted on a three month contract but paid for seven months) could have become a focal point within proceedings had ONI distinctly raised this issue. As it was, Mr Jing was under the university’s IP Statutes which at the time required equity to be split equally between the inventors and the university. The judge didn’t find this to be unfair, however it is interesting to note that Oxford University have since updated and modified their equity split in favour of inventors: the default equity split is 80% for founder researchers and 20% for the university with a 90/10 share being agreed in some situations.

The judge found that OUI’s equity split was within the range of other UK universities and that the concept behind the successful microscope design had been developed in an Oxford lab, by an Oxford professor and assisted by a team of researchers funded by research councils. OUI was therefore well within their right to claim their share of revenue due to the support they provided to ONI.

As a result, the judge found that OUI were entitled to the royalties from the success of ONI. The judgement here should however serve as a reminder to ensure any policy or agreement relating to IP is clear and understood by all parties involved. It further exemplifies the need to agree on IP ownership in an academic context, particularly when there may be a power imbalance between senior and junior members of a HE body.

According to the existing case law of the Boards of Appeal, the standard of proof applicable to allegations of public prior use – when the evidence is in the sphere of both parties – is ‘the balance of probability’. However, when the evidence lies entirely in the sphere of the opponent, usually a higher standard of proof, i.e. ‘beyond any reasonable doubt’ (up to the hilt), applies. The two standards would entail a different degree of proof that an alleged fact is correct or has occurred.

In T 464/20, the Board stresses that the most relevant question is whether the deciding body is convinced that an alleged fact is correct or has occurred. In the case at hand, the opposition division, in acknowledging the public prior use, applied the ‘balance of probability’ standard. The appellant/patentee objected that the applied standard was not the correct one, because only the respondent/opponent had the control of the evidence.

In the decision, in a quite cumbersome sentence, the Board reasoned that even if the Board followed the patentee’s view that practically all the evidence was within the opponent’s control, the Board would still have to be convinced that the choice of the ‘balance of probability’ standard was not correct. The Board was not convinced of the incorrectness of the choice of the standard by the opposition division. In this regard, the Board noted that the opposition division correctly did not base its decision exclusively on the question whether the alleged facts were probable; rather, they were convinced of their correctness. Indeed, the opposition division was convinced both that the delivery of the product at issue was not exclusively in the hands of the opponent and that it had actually occurred.

The Board further relied on two previous Boards of Appeal decisions to support its opinion.

They referred to T 548/08, in particular reasons 4 to 11. T 548/08 deals with the type of standard of proof (‘beyond any reasonable doubt’ versus ‘the balance of probability’) to be applied to assess whether an internet disclosure forms part of the prior art. The Board commented that it was aware of the different views expressed in the case law on the standard to be applied.

However, the Board stated that the European Patent Convention’s (EPC) overarching principle of free evaluation of evidence (referring to decision G 1/12, OJ EPO 2014, A114, point 31) would reconcile the two different points of view. G 1/12’s reason 31 states that the proceedings before the European Patent Office (EPO) are conducted in accordance with the principle of free evaluation of evidence and that this principle would be contradicted by laying down firm rules of evidence defining the extent to which certain types of evidence were, or were not, convincing.

Accordingly, in reason 11, the Board stressed that the facts on which any finding of public availability is to be based must be established with a sufficient degree of certainty in order to convince the competent organ of the EPO that the facts have indeed occurred. This holds true even if the determination is made on the basis of probabilities and not on the basis of absolute certainty (‘beyond any reasonable doubt’).

T 768/20, in particular reason 2.1.2, is the second decision mentioned. This decision addresses the point whether, in assessing Art. 123(2) EPC, the implicit disclosure of a certain feature had to be proven beyond any reasonable doubt. The Board found that the applicable standard is ‘beyond any reasonable doubt’. However, the Board noted in reason 2.1.2:

“Incidentally, the Board wishes to point out that the practical relevance of the distinction between the “balance of probabilities” standard and the “beyond reasonable doubt” standard is often overestimated. Both standards are only fulfilled if the deciding body is persuaded that the alleged fact is true, which is not a matter of “just tipping the balance slightly” (see decision T 545/08, point 8 of the reasons). This is also confirmed by the passage in case law, section III.G.4.3.1, according to which “the balance of probabilities standard [is] met if, after evaluating the evidence, a board [is] persuaded one way or the other” (underlining by this board).”

The Board of T 464/20 then considered the available evidence and concurred with the opposition division that the public prior use was ‘sufficiently’ proved.

Decisions T 464/20, T 545/08 and T 768/20 deal with the standard of proof in different contexts (prior use, internet disclosure, Art. 123(2) EPC). In each of these cases, the competent Board, without denying the distinction between the two standards, appears to emphasise that what matters is that the deciding body is convinced that the alleged fact is correct or has occurred. Therefore, in the case of the standard of probability, it is not sufficient to show that an alleged fact has merely “probably” occurred.