The Enlarged Board of Appeal has just issued its decision in consolidated cases G 1/22 and G 2/22 concerning the EPO’s competence to determine ‘same applicant’ priority issues and the assessment of priority in a PCT application (see our earlier coverage here and here). The decision seems to mark a dramatic relaxation of the EPO’s approach to same-applicant priority, and thus it is strongly pro-applicant/patentee.

First question

The Enlarged Board was asked to answer two questions, the first of which it rephrased thus:

“Is the EPO competent to assess whether a party is entitled to claim priority under Article 87(1) EPC?”

The question was answered as follows:

“The European Patent Office is competent to assess whether a party is entitled to claim priority under Article 87(1) EPC.

There is a rebuttable presumption under the autonomous law of the EPC that the applicant claiming priority in accordance with Article 88(1) EPC and the corresponding Implementing Regulations is entitled to claim priority.”

The first part of the answer does not change current practice: the EPO can continue to assess all aspects of the right of priority. The Enlarged Board held that priority rights are autonomous and that their creation, existence and effects are governed only by the EPC and Paris Convention. A contrast was drawn in this regard with entitlement to a European application, which is governed by national laws and assessed by national courts. The Enlarged Board further recognised the importance of comprehensively assessing patentability, which would only be possible if the EPO has the power to assess priority entitlement.

The second part of the answer signals a major change in the EPO’s approach to assessing priority entitlement. Under the autonomous law of the EPC, it is apparently now enough for the priority applicant to have consented to a priority claim in a subsequent application, there being no formal requirements laid down in this regard (“the EPO should … accept informal or tacit transfers of priority rights”), and the presumption being that consent was given. The presumption of entitlement is rebuttable because “in rare exceptional cases the priority applicant may have legitimate reasons not to allow the subsequent applicant to rely on the priority.” However, the rebuttable presumption is also “strong … under normal circumstances”, and thus a party challenging entitlement to priority “can … not just raise speculative doubts but must demonstrate that specific facts support doubts about the subsequent applicant’s entitlement to priority”.

Support for the rebuttable presumption is said to be found “taking into account (i) that the priority applicant or its legal predecessor must under normal circumstances be presumed to accept the subsequent applicant’s reliance on the priority right, (ii) the lack of formal requirements for the transfer of priority rights and (iii) the necessary cooperation of the priority applicant with the subsequent applicant in order to allow the latter to rely on the priority right.” A priority-claiming application is of course often filed before the priority application is published, thus implying a degree of cooperation between the priority applicant and subsequent applicant.

On the face of it, the new rebuttable presumption approach could put an end to many attacks on same-applicant priority in EPO opposition proceedings – an opponent may have to prove that the applicant for a subsequent application did not obtain consent from the priority applicant in order to claim priority, e.g. the subsequent applicant acted in bad faith. Indeed, the Enlarged Board envisages that the approach “substantially limits the possibility of third parties, including opponents, to successfully challenge priority entitlement.”

In further good news for applicants and patentees, the Enlarged Board also suggests that it should now be possible to fix those rare chain of title priority issues that do arise retroactively: “If there are jurisdictions that allow an ex post (‘nunc pro tunc’) transfer of priority rights …, the EPC should not apply higher standards.”

Second question

The second question, which applied if the Enlarged Board found that the EPO has jurisdiction to determine same-applicant priority, reads thus:

“Can a party B validly rely on the priority right claimed in a PCT-application for the purpose of claiming priority rights under Article 87(1) EPC in the case where

1) a PCT-application designates party A as applicant for the US only and party B as applicant for other designated States, including regional European patent protection and

2) the PCT-application claims priority from an earlier patent application that designates party A as the applicant and

3) the priority claimed in the PCT-application is in compliance with Article 4 of the Paris Convention?”

The Enlarged Board answered the question as follows:

“The rebuttable presumption also applies in situations where the European patent application derives from a PCT application and/or where the priority applicant(s) are not identical with the subsequent applicant(s).

In a situation where a PCT application is jointly filed by parties A and B, (i) designating party A for one or more designated States and party B for one or more other designated States, and (ii) claiming priority from an earlier patent application designating party A as the applicant, the joint filing implies an agreement between parties A and B allowing party B to rely on the priority, unless there are substantial factual indications to the contrary.”

The answer is not surprising in view of the answer to the first question. The threshold for disputing such an agreement between parties A and B is again high: “factual indications … of a substantial nature” are needed, e.g. evidence that “an agreement on the use of the priority right has not been reached or is fundamentally flawed”.

Conclusion

Many patents have been revoked by the EPO based on intervening art deemed relevant because priority entitlement was challenged and the patentee could not provide sufficient proof that the applicant for the European application (or international application designating Europe) was the successor in title to the priority applicant when the European application was filed. It seems likely that in many of these cases, the priority claim would be deemed valid under the rebuttable presumption approach. The Enlarged Board’s decision thus seems to mark a major relaxation of the EPO’s approach to same-applicant priority.

Whether European national courts and the Unified Patent Court also now adopt the rebuttable presumption approach remains to be seen. However, it seems unlikely that the Enlarged Board’s decision will be ignored in these other jurisdictions.

This decision relates to an unusual case of added matter and how considerations typically relevant to sufficiency of disclosure impacted its assessment.

In this case, basis for an amended claim deriving (only) from an example was considered to be undermined by the apparent failure of the medical treatment described in the example to achieve the technical effect required by the main claim. In short, a second medical use claim cannot find basis in an example which does not successfully achieve the therapeutic effect set out in the claims.

The claim in question included the following features:

- “A vaccine comprising in combination non-live antigens of Lawsonia intracellularis, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and Porcine circo virus,” – triplet product combination

- “for use in protection against Lawsonia intracellularis, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and porcine circo virus” – use limitation

- “by intramuscular administration of the vaccine only once.“ – dosage regimen

Example 3 of the application as filed included, amongst other things, two groups of animal subjects (piglets) which were injected intramuscularly with the triple vaccine combination product of Claim 1. One group was injected only once – as per the dosage regimen of Claim 1 – and another group was injected with a booster shot, thus receiving two doses of the combination vaccine and therefore falling outside of the dosage regimen of Claim 1. The example reported that a detectable level of antibodies for Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae was present only in the booster shot group and not in the single dose group (nor in a control group receiving no vaccine). Example 3 thus made clear that the single administration of the vaccine, as claimed, was not successful.

The patent in question was initially opposed on the grounds of added matter (Art. 123(2) EPC) and sufficiency of disclosure (Art 83 EPC) and was revoked at first instance for failing to meet the requirements of sufficiency of disclosure only. The Opposition Division held that: “achieving the purpose recited in the claim was only a matter of sufficiency of disclosure, not of added subject matter” (see T 2593/11, Reasons 3.4).

However, during the appeal against this decision by the proprietor, the Board of Appeal took the view that the technical feature of protection against all three pathogens using the claimed (single administration) dosage regime was not in fact adequately disclosed in the application as filed. At the hearing, the Board considered added matter (Article 123(2) EPC) first and ultimately revoked the patent on that ground without needing to consider sufficiency of disclosure, in contrast with the first instance proceedings.

Whilst it may seem strange for the particular result of an example to be decisive in whether or not a claim to a medical use can be considered to have basis in the application as filed, the Board’s decision makes more sense in light of established case law on novelty of second medical use claims.

“Mere statements that a particular therapy is being explored do not amount to a novelty-destroying disclosure of a second medical use claim which includes the achievement of this therapy as a technical feature” (T 1859/08, Reasons 13).

“A document that describes the administration of a compound to diseased subjects but neither explicitly nor implicitly discloses an effective treatment of the disease by this compound does not directly and unambiguously disclose this treatment” (T 239/16, Reasons 5.2 and 5.3).

Although these earlier decisions relate to novelty, the Board held the view that “the concept of disclosure must be the same for the purposes of Articles 54 and 123 EPC (in view of G 2/10, G 1/03).” In other words, a disclosure that would not be enabling in the sense of novelty, would also not be able to provide basis for an amendment.

When these decisions are considered, it seems clear that an example lacking any positive results cannot, in and of itself, be considered to disclose a medical use, where a positive outcome or improvement/benefit is normally considered implicit in a claim to the treatment or prevention of a disease or condition. This is clearly the case even if the intent or purpose of the example was to evidence that particular claimed treatment.

Nevertheless, it is clear that this decision applies only to the scenario where the example alone is being assessed for basis and not alongside other disclosures in the specification as filed which might normally be expected to be present. As many readers will know, using a specific example as basis for an amendment to a claim under European Patent Office (EPO) practice can often fall foul of added matter issues, particularly when only certain features are extracted (‘cherry picked’) from the example and imported into a claim and other features are left behind (as in the case of an ‘intermediate generalisation’).

In this particular case, the Board could seemingly have further justified the finding of added matter on the basis that there is an inextricable link in Example 3 of the claimed (single administration) dosage regime and a failure to inoculate against Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Importing the dosage regime from the example, without also the failed result reported therein, could therefore also be characterised as an unallowable intermediate generalisation under EPO practice.

This decision reaffirms the importance of providing disclosure of technical effects in the description, and not just confining them to discussion in the context of a specific example, in order for such disclosures to potentially serve as basis for a claim amendment under EPO practice. It also potentially adds further to an opponent’s toolkit in objecting to scenarios in which a claimed technical effect is based only on disclosures taken from examples, particularly where there is any ambiguity over the results achieved in those examples.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in the field of Chemistry to Moungi G. Bawendi, at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Louis E. Brus, at Columbia University, and Alexei I. Ekimov at Nanocrystals Technology Inc., for their roles in the discovery and synthesis of quantum dots.

Quantum dots are semiconducting nanoparticles having diameters as small as a few nanometres. Quantum dots are often made up of only a few thousand atoms. To put this in perspective, a quantum dot has the same relationship to the size of a football, as the football has to the size of the Earth. Due to their size, quantum dots have certain properties of both bulk semiconductor materials and individual atoms or molecules, making them useful across various applications.

When quantum dots are illuminated, electrons are excited from their valence band into their conductance band (photoexcitation). When the excited electron drops back into the valence band, energy is released in the form of light. This is a phenomenon known as photoluminescence. The optoelectronic properties of quantum dots can be adjusted by changing their size and possibly even their shape. The wavelength of the photoluminescence can therefore be fine-tuned in order to emit a specific desired wavelength of visible light.

Quantum dots were first intentionally prepared by Alexei Ekimov during experiments on the effects of dopants on the colour of glass. Ekimov discovered that glass containing copper chloride crystals would have a different colour depending on the crystal’s size. However, Ekimov lived in the Soviet Union where his work was not accessible to scientists on the other side of the iron curtain. Unaware of Ekimov’s work, Louis Brus was the first to prepare quantum dots floating freely in a solution. Brus was working with cadmium sulphide nanoparticles when he discovered that their optical properties would change over time as the particles grew in size.

Almost a decade later, a major breakthrough was achieved by Moungi Bawendi who succeeded in growing nanocrystals of reliable and specific sizes. Bawendi’s preparation methods were easy to use and made quantum dot science much more accessible to scientists around the world.

Today, quantum dots find application in various optoelectronic devices. The light emitting properties of quantum dots are useful in the emerging technology of quantum dot display screens. Quantum dot displays allow for the wavelength emitted by the quantum dots to be precisely controlled. This results in vibrant and true-to-life colour reproduction, surpassing that of conventional LCD and OLED displays. Quantum dot displays offer a more visually impressive display as well as being more eco-friendly and energy-efficient than conventional display devices.

Quantum dots are also capable of the very similar process of turning light into electricity, which forms the basis of solar cells. Unlike traditional solar cell materials, quantum dots can have a wide range of band gaps depending on their size. This means that by taking advantage of mixtures of quantum dot sizes, these mixtures can be made to absorb a wide range of wavelengths from the sun’s rays. This can lead to much more efficient electricity production than is possible using conventional solar panels, which only absorb a narrow range of wavelengths allowing much of the energy to go to waste.

It is clear that Ekimov, Brus, and Bawendi have made a considerable scientific contribution, which will enable whole new fields of research and technology to be realised. Development of new quantum dot based optoelectronic devices is ongoing and is certainly an area in which we expect to see more exciting developments in the future.

We are thrilled to share that Mathys & Squire has upheld its position in the 2024 edition of The Legal 500 for both PATMA: Patent Attorneys and PATMA: Trade Mark Attorneys categories. It is with great satisfaction that we announce a notable increase in the number of our fee earners receiving individual recommendations in this year’s guide.

Patent Partners Chris Hamer, Alan MacDougall, Martin MacLean, Jane Clark, Paul Cozens, Dani Kramer, Philippa Griffin, Juliet Redhouse, James Wilding, Sean Leach, James Pitchford, and Managing Associate Laura Clews who have been listed in the guide for a number of years, as well as Annabel Hector and Andreas Wietzke, who are newly ranked, are all featured in the 2024 edition of the directory.

Mathys & Squire’s trade mark team has also received recognition in the directory. From our trade mark practice, Partners Margaret Arnott, Rebecca Tew andGary Johnston, and Managing Associate Harry Rowe, have been ranked.

The firm received glowing testimonials for its patent and trade mark practices:

“The key strengths that Mathys & Squire brings to their patent practice are legal excellence, strong communication skills, and unparalleled dedication to client matters.”

“Mathys & Squire is highly recommended for is exceptional professionalism, expertise, and commitment to providing high-quality legal advice. The team’s depth of knowledge in IP law is evident in the insightful guidance it provides.”

“Jane Clark is very experienced in prosecution and oppositions in the field of medical technology.”

“Dani Kramer is highly recommended as an experienced professional with a proven track record in IP matters. He brings valuable expertise and strategic insights to clients, and his dedication and knowledge make him a reliable choice for IP-related services.”

“Andreas Wietzke is highly recommended with extensive experience and expertise in IP law. He provides exceptional legal counsel and support, and his dedication, professionalism, and strategic insights make him a valuable asset in navigating complex IP matters.”

“Paul Cozens has stand-out analysis and industry nous.”

“Annabel Hector is excellent at patent prosecution.”

“Juliet Redhouse’s legal abilities, scientific and technical knowledge, and client engagement is exceptional.”

“Gary Johnston has enormous experience and sound common sense.”

“The trade mark team has proven to be professional, efficient, and reliable.”

“Margaret Arnott’s experience and guidance is valued.”

For full details of our rankings in The Legal 500 2024 guide, please click here.

We extend our gratitude to all our clients and connections who participated in the research, and we extend our congratulations to our individual attorneys who have earned rankings in this year’s guide.

Black History Month is a time to honour and celebrate the significant contributions of black people in various fields throughout history. While we often reflect on the great leaders and civil rights activists, it’s equally important to acknowledge the black innovators and inventors who have made lasting impacts on the world. In this article, we pay tribute to some of the most remarkable individuals whose innovations and inventions have left an indelible mark on science, technology, and medicine.

Lewis Latimer’s profound impact on electrical engineering and the lightbulb

Latimer (1848-1928) was a brilliant inventor and draftsman whose contributions to electrical engineering were foundational to the development of the modern lightbulb. As a key member of Thomas Edison’s team, Latimer played a critical role in improving the design of the incandescent lightbulb, developing a more efficient and longer-lasting filament. His work not only extended the practicality of electric lighting but also paved the way for the widespread adoption of electricity in homes and businesses.

Granville T. Woods’ legacy in the railway industry

A prolific inventor, Woods (1856-1910) held more than 60 patents in various fields, primarily focused on electrical and mechanical innovations. One of his most notable inventions was the multiplex telegraph, which greatly improved the efficiency of communication. Woods’ inventions also extended to the railway industry, where he developed a variety of safety devices and systems that improved the safety and efficiency of rail travel.

George Washington Carver’s transformation of the agricultural industry

Carver (c.1860-1943) was an agricultural scientist and inventor whose work revolutionised farming practices. Born into slavery in the 1860s, he overcame immense challenges to become one of the most influential botanists and inventors of his time. He is best known for his extensive research on peanuts and sweet potatoes, discovering hundreds of innovative uses for these crops. Carver’s inventions ranged from new peanut-based food products to cosmetics and industrial materials, fundamentally transforming the agricultural industry and improving the livelihoods of countless farmers.

Majorie Stewart Joyner’s permanent wave machine

A successful cosmetologist and businesswoman, Joyner (1896-1994) received a patent for her invention of a permanent wave machine in 1928. Her invention revolutionised the way hair styling and haircare were approached, making the process more efficient and accessible.

Charles Drew’s innovative influence on blood transfusion medicine

Dr. Drew (1904-1950) was a renowned physician, surgeon, and medical researcher who made groundbreaking contributions to the field of blood transfusion and blood banking. During World War II, he established the first successful large-scale blood bank program, saving countless lives. Drew’s research on blood plasma preservation and separation techniques laid the foundation for modern blood transfusion medicine, ensuring the safe storage and transport of blood products for medical emergencies.

Patricia Bath’s lasting impact on cataract surgery

An ophthalmologist, inventor, and advocate for healthcare equality, Bath (1942-2019) received a patent for her invention, the Laserphaco Probe, which revolutionised cataract surgery by making it more precise and less invasive. Dr. Bath’s groundbreaking work not only restored sight to countless patients but also inspired future generations of black innovators in the medical field.

Maggie Aderin-Pocock’s contributions to space science and innovation

Dr. Aderin-Pocock (1968-) is a British space scientist and science communicator. She is best known for her work in engineering, and holds several patents related to her inventions, including devices designed to improve observational instruments for space telescopes.

During Black History Month, we celebrate the legacy of black innovators and inventors whose contributions have shaped our world for the better. Their work not only improved the lives of their contemporaries but continue to benefit humanity today. As we honour their achievements, let us also remember the importance of fostering diversity and inclusion in all fields to ensure that future generations of innovators have the opportunity to make their mark on history.

Intellectual property (IP) is a key asset for life sciences companies, especially in the form of patents. Valuation of these crucial assets requires a deep understanding of how the industry works and its characteristics.

Drug development and healthcare innovations require significant financing and long timelines to get to the market. Alongside this, the industry’s development milestones are defined by the regulatory process of approval, and due to the very uncertain nature of life sciences research, the outcome is binary. Either the project is a success and brings hundreds of millions to billions of dollars of revenue, or it is a failure, with an average of 92.1% of developments in the pharmaceutical sector not succeeding. Companies mitigate this risk by working on a diverse portfolio, and once one project is successful, its revenues cover the losses incurred by other projects (similar to the venture capital model).

Understanding the value of IP and projects in the life sciences sector allows the owners to make better strategic decisions about its prioritisation, budgeting, licensing or even abandonment.

Valuing the IP in life sciences businesses is complex as there are several factors to be considered, each with its own intricacies, complexities, and uncertainties. These include:

- The reason for valuation – this can be for licensing, fundraising, asset backed lending, mergers and acquisitions, litigation, or accounting purposes.

- The stage of the IP being valued and its details.

- The cashflow forecast attributed to the IP, its timing and success rates. These can be further split into:

a. Costs required to take the innovation (protected by the IP) to market;

b. Sales generated once the product (protected by the IP) reaches the market;

c. The likely timeline for development and sales; and

d. The probability of success for the innovation at each stage/key milestone. - The discount rate to be used when calculating the present value of the future cashflows.

The purpose of the valuation has impact on what type of valuation model is used. Similarly, the details of the IP, its stage, and what product it protects influence the factors involved in the valuation – modelling of the potential sales, discount rate, costs of development, probability of success.

For pharmaceutical companies, patents are the most important type of IP, and one would look at least at the following to get an understanding of the asset – ownership of IP and any outstanding contractual provisions, stage of prosecution, remaining useful lifetime, patent landscape/freedom to operate, any legal actions, examination of the patent and opinions from the examiner(s), and what product it protects or is likely to protect (especially in early stages of life sciences developments, as it is very difficult to pinpoint the exact designation of the drug). The reason patents are so important in the pharmaceutical industry is that once a drug comes out of patent protection, sales plummet drastically due to generic drugs taking market share and offering lower prices than the drug previously protected by a patent.

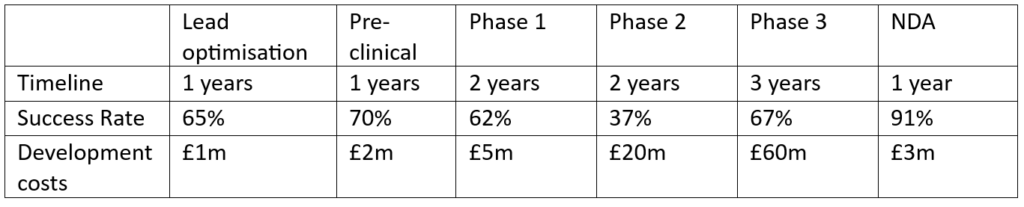

The life sciences development process is very well defined, from lead drug candidate to Phase 3 and New Drug Application, but the timelines, costs, success factors, and potential sales, all depend upon disease area and specifics of the IP/technology. The development information required for an IP valuation is outlined in the table below with some hypothetical numbers.

Once the drug candidate reaches the market, it starts generating sales to cover the development costs of all the failed projects and begins to produce profits for the company. The revenue can be modelled with a sales curve as the drug enters the market and the peak sales, which are the highest sales number a drug will reach during its patent protection lifetime. They can be determined from existing data about average or median sales numbers for a certain disease category, or with a bottom-up approach. The latter approach estimates the peak sales number based on the patient population numbers for the drug (population for geographies of interest, epidemiology, symptomatic population, diagnosed patients, access to health care, treatment rate, etc.), market share (indication, strength of the company in the disease area, brand power, etc.), and price.

There are four main methods that are used for valuing life sciences IP – the discounted cash flow method, the risk adjusted discounted cash flow method (decision tree), Monte Carlo valuation and real options valuation. We will demonstrate the different methods in a future article, further exploring the life sciences IP valuation process.

Mathys & Squire Consulting has experience in valuing life sciences and biotech related IP. Please get in touch with any IP valuation enquiries you might have.

The 2023 Global Innovation Index (GII) has been formally unveiled by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). This latest GII assesses 132 nations, monitoring worldwide innovation patterns in the midst of a challenging landscape marked by sluggish economic rebound from the COVID-19 pandemic, elevated interest rates, and geopolitical tensions. Nonetheless, it also reflects the potential of forthcoming innovation waves in the digital age and deep science, along with ongoing technological advancements.

For the 13th consecutive year, Switzerland secures the leading position, with Sweden, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Singapore following closely. In terms of innovation progress over the past decade, middle-income economies such as China, Turkey, India, Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia and Iran have made substantial strides, although China has now slipped out of the ten following their improved 2022 ranking.

Results of the global top 100 Science & Technology cluster rankings

The 2023 GII also continues to examine the most prominent technology innovation hubs for the year. These ‘science and technology (S&T) hubs’ focus on the global centres of innovation characterised by the greatest concentration of scientific authors and inventors.

Tokyo–Yokohama in Japan continues to maintain its leading position, with Shenzhen–Hong Kong–Guangzhou in China closely trailing, followed by Seoul in the Republic of Korea.

Among S&T-intensive clusters relative to population density, Cambridge in the United Kingdom and San Jose–San Francisco, CA, in the United States take the top two spots. Oxford in the United Kingdom, Eindhoven in the Netherlands, and Boston–Cambridge, MA, in the United States follow suit. Notably, Munich in Germany has also secured a place in the global top 10 most S&T-intensive clusters.

For the first time, China leads the list of countries with the highest number of clusters among the top 100, boasting a total of 24. The United States comes in second with 21 clusters, followed by Germany with nine.

The Global Innovation Tracker 2023

The Global Innovation Tracker monitors essential patterns in investments related to innovation, gauges the speed of technological advancements and their acceptance, and assesses the consequential socioeconomic outcomes.

It is important to understand how innovation is adapting amid the worldwide turbulence generated by increased inflation, escalating interest rates, and geopolitical tensions in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the latest findings from the Global Innovation Tracker, emerging breakthrough technologies are still offering fresh prospects, yet the societal effects of innovation remain limited.

Key findings from the past year include a mixed performance in science and innovation investment, particularly in light of numerous challenges, and a downturn in innovation financing. While the number of scientific publications continued to rise, the growth rate was slower. Projections indicate an expected real term increase in global government R&D budgets, and major corporate spenders substantially increased their R&D expenditure. However, it remains uncertain whether this can offset the impact of rising inflation. International patent filings stagnated, and venture capital investments experienced a significant decline in value, following the exceptionally high levels seen in previous years, reflecting a deteriorating climate for risk financing.

In the realms of information technology, health, mobility, and energy, significant technological advancements persist, creating fresh opportunities for global development. Computing power remains historically robust, and the costs associated with renewable energy and genome sequencing continue to decrease. A noticeable uptick in technology adoption is gradually expanding access to safe sanitation and connectivity. Electric vehicle adoption is on the rise, and there is a growing demand for increased automation, leading to greater robot installations. However, for most innovation indicators, overall adoption rates still fall in the medium-to-low range, and many countries continue to face insufficient availability of radiotherapy for cancer treatment.

The socioeconomic impact of innovation remains limited. The COVID-19 crisis has disrupted labour productivity, which has currently reached a standstill, and life expectancy has declined for a second consecutive year (although healthy life expectancy is increasing, albeit at a slower pace). Carbon dioxide emissions have continued to grow, albeit at a slower rate than the post-pandemic surge seen in 2021, with no global reductions on the horizon.

The 2023 GII paints a complex picture of the global innovation landscape. In the face of formidable challenges such as the lingering economic effects of COVID-19, alongside growing geopolitical tensions, businesses around the world are now navigating the new innovation landscape in which we find ourselves.

Over the past few months, recent decisions concerning the notion of plausibility and the ability to rely on evidence not provided at the time of filing have been released both at the European Patent Office (EPO) and in the UK. This article will explore the rulings from both jurisdictions and determine the extent to which the two are aligned.

Brief background

The concept of plausibility does not appear in either the Patents Act or the European Patent Convention. Nonetheless, in recent years it has become a major talking point, forming the basis of several decisions across both jurisdictions. Plausibility generally concerns the idea that something (e.g., a technical effect) must have been plausible to the skilled person at the time of filing, and largely relates to what was disclosed in the application as originally filed.

Europe – G2/21

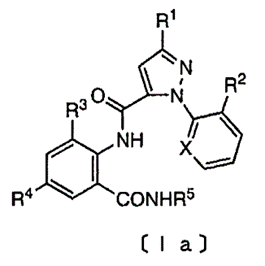

The decision stemmed from European patent 2484209, which relates to an insecticide made up of a particular combination of compounds. Specifically, claim 1 of the granted patent relates to a composition comprising two insecticidal compounds – thiamethoxam and ‘a compound of formula 1a.’ A template for formula 1a is shown below.

The claim itself defines R1-R5 and X as particular chemical groups, and also excludes three particular compounds from falling under the scope of formula 1a. Although the cited prior art had disclosed thiamethoxam and compounds of the aforementioned formula 1a individually, no combination of the two had been recited. With regard to inventive step, the applicant argued that the technical effect of this specific combination was a synergistic effect of the compounds against two particular species of moth and provided data to support this.

The granted patent was opposed, during which the opponent filed new data which appeared to contradict the proprietor’s arguments by suggesting that a combination of thiamethoxam and chlorantraniliprole (a compound that falls within the scope of formula 1a) did not have a synergistic effect against one of the two moth species. This would mean that the technical effect was not achieved across the whole scope of the claims.

In response to this, the proprietor provided post-published evidence in the form of data allegedly showing that the synergistic effect was achieved against a third species of moth. The Opposition Division was satisfied that the technical effect could therefore be reformulated as providing a synergistic effect against the third moth species. While the Opponent did not dispute this, they did argue that this synergistic effect against the third species of moth was not plausible from the application as originally filed and so requested that the post-published evidence be dismissed.

The subsequent decision to reject the Opposition was appealed, with the case eventually making its way up to the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBA) in a bid to ascertain the extent to which the post-published evidence could be relied on.

Ahead of the ruling, it was anticipated that the EBA would align their decision with one of the three so-called standards of plausibility, which are described below.

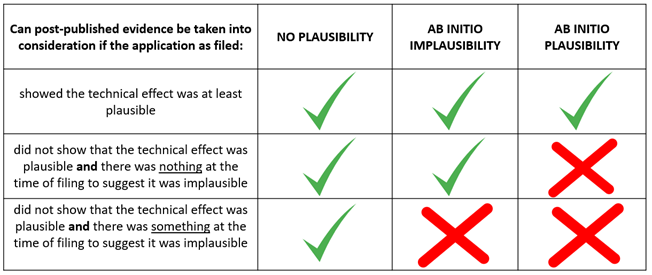

Standards of plausibility

- No plausibility – this is the lowest bar for plausibility; in fact, it rejects the concept all together. If this standard were to be applied, it would mean that post-published evidence could be considered regardless of detail and regardless of whether a technical effect would have been plausible. Such an approach is inconsistent with the EPO’s problem-solution approach, and so it was never envisaged that this standard would be applied.

- Ab initio implausibility – this is an intermediate bar, which states that post-published evidence can only be disregarded if there is a legitimate doubt that the technical effect on the filing date of the application. As long as the technical effect would have been plausible, the evidence can be admitted. In such an instance, the burden of proof would rest on an Opponent to show that the technical effect was not plausible.

- Ab initio plausibility – this is the highest bar for plausibility, which states that post-published evidence can only be taken into account if there is legitimate reason to believe that the technical effect had been achieved at the filing date. The default assumption is that the effect is implausible, and the onus would be on the applicant to show that the effect was in fact plausible at the time of filing.

The below table helps to summarise what types of evidence can be admitted according to the three different standards.

The Board of Appeal provided the following questions to the EBA.

- Should an exception to the principle of free evaluation of evidence be accepted in that post-published evidence must be disregarded on the ground that the proof of the effect rests exclusively on the post-published evidence?

- If the answer is yes, can the post-published evidence be taken into consideration if, based on the information in the patent application in suit or the common general knowledge, the skilled person at the filing date of the patent application in suit would have considered the effect plausible?

In other words, should the ‘ab initio plausibility’ standard be applied?

- If the answer to the first question is yes, can the post-published evidence be taken into consideration if, based on the information in the patent application in suit or the common general knowledge, the skilled person at the filing date of the patent application in suit would have seen no reason to consider the effect implausible?

In other words, should the ‘ab initio implausibility’ standard be applied?

In response to question 1, the EBA concluded that the principle of free evaluation of evidence could not be used to disregard evidence per se, since doing so could deprive a party of the basic legal procedural right to be heard and to provide evidence. As such, evidence submitted to prove a technical effect relied upon for inventive step may not be disregarded solely on the ground that such evidence was post-published.

Turning to questions 2 and 3, the EBA (perhaps wisely) steered away from the concept of plausibility. Noting that the term itself “does not amount to a distinctive legal concept or a specific patent law requirement under the EPC”, the EBA deemed plausibility to be nothing more than a ‘generic catchword’ and instead focused the issue at hand towards precisely what the skilled person would have understood from the application at the time of filing, rather than what they might have considered credible.

With this in mind, the EBA came to the conclusion that a technical effect may be relied upon for inventive step if the skilled person, having the common general knowledge in mind and based on the application as originally filed, would consider the technical effect as being encompassed by the technical teaching and embodied by the same originally disclosed invention. On this basis, the patentee was able to rely on their post-published evidence concerning the third moth species and so the claims were found to be inventive. The appeal was therefore dismissed.

A key point to note from this is that there is no requirement for such a technical effect to be directly supported by data in the original application – an effect that is only supported by post-published evidence may still be sufficient to be considered as encompassed by the technical teachings within.

The outcome is largely positive news for applicants, since it has avoided some of the difficulties that may have arisen from a verdict falling directly within the constraints of the ab initio plausibility standard. The fact that post-published evidence can be relied on will be particularly welcome news to applicants for whom early filings are a necessity. Nonetheless, the ruling does swing the burden of proof back to the applicant, and it will therefore be crucial for applicants to strike a balance between getting applications on file promptly and ensuring that there is sufficient data to support any technical assertions made later on during prosecution.

UK – Sandoz v BMS ([2023] EWCA Civ 472)

Prior to this decision, the benchmark for plausibility in the UK was Warner-Lambert v Actavis, in which it was ruled that that a patent specification must render plausible, at the filing date of the application, that the technical effect embodied in the claimed invention can be achieved. The ruling laid the ground for the UK Courts to treat plausibility as a valid legal concept (despite the fact that it does not appear in the Patents Act) and has ensured that it remains part of the common vernacular among UK attorneys.

However, as described above, the EPO decision G 2/21 seemingly renounced plausibility as a legal concept. This left the UK Courts in an awkward position whereby the Supreme Court deemed plausibility to be a legal concept and requirement for grant, yet the EPO deemed the opposite. It was therefore hoped that the present ruling might be able to reconcile these two decisions.

The case stemmed from European patent EP(UK) 1427415. Claim 1 was directed towards apixaban, an anticoagulant medical compound. This compound is a factor Xa inhibitor, and the alleged technical effect of the claim was the compound’s use against thromboembolic disorders (e.g., blood clots).

The specification itself had no specific data to directly support apixaban’s usefulness against such disorders. Indeed, the closest the description came to this was a section in which it recites that “a number of compounds of the present invention were found to exhibit a Ki of <10 µM, thereby confirming the utility of the compounds of the present invention as effective Xa inhibitors.” While this generic statement suggests that a large number of compounds (including apixaban) could be used as inhibitors of factor Xa, there was no data specifically showing apixaban’s capabilities in this regard. Nonetheless, the application proceeded to grant, after which a revocation action was brought by Sandoz and Teva on the grounds of sufficiency and inventive step, due to the supposed lack of plausibility.

The High Court deemed that apixaban’s use as a factor Xa inhibitor would not have been plausible to the skilled person at the time of filing, and therefore found the patent to lack sufficiency and inventive step. BMS appealed, arguing that “in the case of a claim to a single chemical compound, there is no requirement that the specification makes it plausible that the compound is useful.” BMS further argued that “it is sufficient that the specification discloses the structure of the compound and a method of synthesis and contains an assertion of potential utility for the compound, provided that that assertion is not manifestly speculative or wrong.”

Rather than aligning with the EPO on the matter of plausibility, the Court of Appeal conceded that, at least in this instance, it was bound by the Supreme Court decision in Warner-Lambert v Actavis. The recent EBA decision in Europe did not merit a departure from the precedent set in the UK Courts. Arnold LJ deemed that the earlier Supreme Court majority decision in Warner-Lambert was equivalent to an ab initio plausibility test (with the minority decision relating to an ab initio implausibility test), and despite considering several of the points raised in G 2/21, held that the plausibility standard set out in Warner-Lambert should remain the same. With reference to G 2/21, he commented that the EBA decision should be treated as an endorsement of the ab initio plausibility standard that formed the basis of the majority decision in Warner-Lambert, using this as justification not to deviate from the earlier Supreme Court ruling.

Arnold LJ subsequently upheld the decision of the High Court and ruled that post-published data could not be used as a substitute for sufficient disclosure in the specification. In his remarks, he stated that the description “gives the skilled team no reason for thinking that there is a reasonable prospect that the assertion will prove to be true”, adding that “it is therefore speculative.”

Whether or not BMS attempt to elevate the matter to the Supreme Court remains to be seen, but in any case, the idea of plausibility in UK patents will remain a hot topic. The Supreme Court is due to hear the appeal of Fibrogen v Akabia in March 2024, which will no doubt build upon the decisions made in Sandoz vs BMS.

For the time being, it appears that rather than aligning, the plausibility approaches in the UK and in Europe are diverging further. In particular, the UK approach appears to be less favourable to applicants than its European counterpart, and applicants are advised to ensure that they have sufficient data in their specifications to back up any technical assertions that may be made during prosecution.

Mathys & Squire is delighted that Partners Sean Leach, Anna Gregson, Dani Kramer and Martin MacLean have all been identified in the 2023 edition of IAM Strategy 300: The World’s Leading IP Strategists. This prestigious acknowledgment celebrates individuals who are at the forefront of crafting and executing strategies to optimise the worth of intellectual property (IP) portfolios. The guide features professionals from various backgrounds, including service providers, corporations, research institutions, and universities, who are driving innovation in IP strategy development and implementation.

Recognised as top-tier experts in IP strategy, these individuals are selected through confidential nominations and subjected to thorough research interviews with senior figures from the global IP sector, including senior corporate IP managers across North America, Europe, and Asia, as well as external IP service providers. After this meticulous assessment, only those possessing outstanding skill sets and profound understanding of IP value generation, creation, and administration earn a spot in the IAM Strategy 300.

The 2023 rankings are available via the IAM website.

We would like to thank our clients and contacts who took the time to provide feedback to the research team at IAM Strategy 300.

We are pleased to announce the appointment of a Partner and Head of Trade Marks Helen Cawley.

With over 20 years’ of experience in the trade mark field, both in-house and in private practice, Helen joins from European intellectual property law firm D Young & Co LLP. Helen’s expertise lies in contentious matters, as well as clearance searches and prosecution work.

Helen’s role at Mathys & Squire will be to further develop the trade mark practice, with an emphasis on long term strategic growth.

Throughout her career, Helen has gained a wealth of experience in trade mark prosecution and portfolio management, and is well known for her work on oppositions and cancellation actions for multinational brands, as well as non-profit organisations.

She is a member of the Chartered Institute of Trade Mark Attorneys (CITMA) and the International Trade Mark Association (INTA). Helen regularly attends INTA conferences – both the Annual and Leadership meetings. Regular travel has enabled Helen to develop a strong network of contacts throughout the world, most notably in the USA and Japan.

Helen has also overseen training and development of trade mark attorneys as well as trade mark paralegals and all related support services.

Alan MacDougall, a senior Partner at Mathys & Squire, says: “We are very excited to welcome Helen to our team of trade mark attorneys. Trade marks is an area that we have been growing as a firm and is an important part of our overall strategy.”

Helen’s experience will stand Mathys & Squire in good stead as we look to take our trade mark practice to the next level.”

Helen Cawley says: “I am delighted to be joining Mathys & Squire and thrilled to have the opportunity to lead their renowned trade marks team. Together, we can take the next major step in furthering our strategic development and growth.”

This release has been published in The Trademark Lawyer and Solicitors Journal.