An article by Partner Andrew White and Associate Jessie Harrison has been published in IAM Magazine giving insight on why the UK patent system needs an overhaul to better accommodate AI-related innovations and foster a more conducive environment for technological progress.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is driving innovation across a host of industries, from healthcare and finance to transportation and entertainment. However, the UK’s patent system seems to be struggling to keep pace with these rapid advancements. As the innovation landscape changes, this article will explore why the UK patent system requires an overhaul to better accommodate AI-related innovations and promote a more conducive environment for technological advancement.

The global artificial intelligence market size is expected to grow twentyfold between 2021 and 2030, from about USD 100 billion in 2021 to nearly USD 2,000 billion in 2030 (Statista 2023). In order to position the UK as a global centre for AI and data-driven innovation, it is important to ensure that the UK can provide the best environment for developing and commercialising AI technologies.

This article, first written for and published in IAM Magazine on 31 August 2024, considers the current ambiguity in UK patent law and its competitive disadvantage from a global perspective. To read the full article, click here.

Commentary by Partner Nicholas Fox has been featured in Law360, Global Legal Post, World Intellectual Property Review, Managing Intellectual Property, Commercial Dispute Resolution, Solicitors Journal, discussing the Unified Patent Court’s (UPC) decision to grant Mathys & Squire’s access to evidence in a Unified Patent Court case between Astellas and Healios.

Read the extended press release below.

Background

Mathys & Squire, the intellectual property law firm, had brought a test case to try and improve the transparency of the operations of the UPC. Previously commented on the following articles:

- Mathys & Squire files UPC test case in support of open justice

- Court hearing on public access to evidence in Unified Patent Court to be held in February 2024

- UPC Court of Appeal interprets law narrowly in transparency test case

- A further blow to transparency at the UPC?

- UPC releases pleadings to the public, but questions remain

- Update on Mathys & Squire test case in support of open justice

- Are written proceedings before the UPC truly public? A tale of three access requests

In recent decisions the UPC had been restricting the access of third parties to pleadings and evidence in UPC cases that should have been accessible on request.

The principles of openness and transparency in Court proceedings and the rights of third parties to access public documents are well established principles in International and European law.

The UPC is a new court system (just over a year old) which will have the power to enforce patents across much of the European Union.

Comments from Nicholas Fox, Partner at Intellectual Property Law firm Mathys & Squire: “We are delighted that the Unified Patent Court has finally granted our request to access the pleadings in this case.”

“However, the way in which our request has been processed still raises significant concerns about the UPC commitment to transparency and open justice.”

“It has taken more than 8 months for the court to process our request. The exceptionally slow processing of the request has delayed our access until after the underlying case was settled.”

“The Judge-Rapporteur has previously stated an intent that the access request would be processed “expeditiously” as soon as an appeal relating to another document access request had been concluded. Those appeal proceedings concluded on 10 April and yet the Court has taken more than 4 months to process our application and issue a decision granting our access request.”

“So far, the UPC has yet to grant access to written pleadings and evidence in a case prior to an underlying matter being concluded.”

The European leg of ‘TAYLOR SWIFT THE ERAS TOUR’ has concluded, leaving fans ‘Enchanted’ as Taylor Swift continues her 152-date global tour, breaking records along the way. She surpassed Michael Jackson’s record for the most performances at Wembley by an international artist during a single tour, with eight nights at the iconic venue. In the UK alone, Swift performed to nearly 1.2 million fans, contributing an estimated £1 billion to the nation’s economy. The singer-songwriter is undoubtedly a huge success and has managed to build on her creative talents to establish a global brand. In the highly competitive and ever-evolving landscape of the music and entertainment industry, Intellectual Property is a crucial asset for artists and Taylor is definitely not ‘Fearless’ when it comes to protecting her IP.

Brand recognition on this scale requires consistent promotion and exposure with the risk that creative works and unique elements are easily accessed and reproduced. To protect her interests, Taylor Swift has registered numerous trade marks at the UKIPO (and internationally), including her name ‘TAYLOR SWIFT’, her fan base ‘SWIFTIES’, albums such as ‘FOLKLORE ALBUM’ and iconic song lyrics such as ‘CAN YOU JUST NOT STEP ON OUR GOWNS’. All of these are synonymous with the distinctive brand, image, and musical style that her SWIFTIES love and the artist’s foresight in securing registered protection has allowed her to promote and commercialise her brand with the assurance that legal protection is in place. All vital for building a loyal fan base and creating long-term success.

Trade marks can be licensed or franchised, creating additional revenue streams which in this case have proven very valuable. Merchandising is a significant income source in the entertainment industry and by having her song lyrics and phrases registered as trade marks, Taylor is able to control any merchandise associated with her brand. When fans purchase products bearing the trade marks of their favourite artists or bands, they contribute to the overall revenue generated beyond just music sales and concert tickets. Forbes reported that the Eras Tour merchandise generated $200 million in 2023. Just in case you were thinking about using ‘TAYLOR SWIFT THE ERAS TOUR’ to create any merch, it is already protected and has been with effect from April 2023, before the tour was announced. Establishing rights ahead of launch or promotion has maintained a competitive edge and provided Taylor’s people with the tools they need to address any early, unauthorised attempts to profit from the tour. This strategy is one that other artists and online creators can use to protect their popularity and success, particularly in a world where songs and catch phrases can quickly go viral and be widely adopted.

Taylor has also had to manage challenges with the laws of Copyright following her move in November 2018 to a new record label.

In the UK, copyright is governed by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, which safeguards original works such as literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic creations, including sound recordings. The US equivalent, the Copyright Act of 1976, protects ‘original works of authorship’ that are fixed in a tangible medium of expression. This includes literary, musical, dramatic, and artistic works, as well as sound recordings. The copyright for a musical track can be divided into two parts: the musical composition, which includes the lyrics and melody and is typically controlled by the artist, songwriter, or composer, and the sound recording, often referred to as “the master” which is generally managed by the record label. This division can lead to conflicting interests, as record labels and managers involved in the recording process seek to profit from their share of the copyright royalties.

For Taylor Swift, this meant that while she owned the copyright to the musical compositions of her albums, the masters for her first six studio albums were held by her then record label, Big Machine Records. This ownership gave the label control over her ability to perform her original music and allowed them to continue profiting from licensing these songs for use in television and film. Following her split with the label, Swift’s highly publicised dispute with Big Machine Records brought significant media attention to the issue, underscoring important aspects of copyright law in the music industry.

Taylor Swift’s, decision to re-record her earlier albums and brand them as ‘TAYLOR’S VERSION’ has been a strategic and well-advised move, allowing her to avoid copyright issues with the original sound recordings and reclaim control over her master’s and music licensing. Additionally, the name and registered trade mark of the re-recordings, ‘TAYLOR’S VERSION’, has become a powerful marketing tool, gaining widespread recognition and appearing on merchandise, promotional campaigns, and even featured on the Transport for London map during her tour!

Taylor’s fans were easily convinced to purchase and stream only ‘TAYLOR’S VERSION’ of their favourite tracks whilst the surrounding publicity raised the artist’s profile even further and has no doubt boosted her already huge fan base.

Adding to her record-breaking achievements, ‘Fearless (Taylor’s Version)’ was Taylor’s first re-recorded album and the first re-recorded album to ever reach No. 1 on the Billboard charts. According to Billboard, ‘Fearless (Taylor’s Version)’ has earned 1.81 million equivalent album units, while the original version of Fearless has earned 535,000 equivalent album units. Since its release, Fearless (Taylor’s Version) has earned more than 3 times as many units as the original. Since the release of ‘Red (Taylor’s Version)’, another chart topper, the re-recording has earned 3.32 million equivalent album units, compared to 390,000 units for the original ‘Red’ album. Contributing to the impressive album unit totals for the two previously re-recorded albums, ‘Fearless (Taylor’s Version)’ has accumulated 1.47 billion on-demand song streams since its release, compared to the 680.39 million streams for the original ‘Fearless’ in the same timeframe. Similarly, since its release in November 2021, ‘Red (Taylor’s Version)’ has achieved 2.86 billion on-demand song streams, while the original ‘Red’ has earned 476.48 million. Although the original albums still receive millions of streams, ‘TAYLORS VERSION’ has significantly surpassed them, redirecting the associated royalties.

Key takeaways:

Taylor Swift’s IP strategy has significantly strengthened her brand, provided robust legal protection, and created lucrative commercial opportunities. Her copyright dispute has highlighted the often-restrictive nature of contracts for emerging artists and the importance of IP awareness in considering any commercial arrangement. Swift has shown current and emerging artists how effectively managing intellectual property can be a powerful marketing tool, helping to differentiate themselves and protect their achievements. By registering trade marks for her name, signatures, tours, fanbase and lyrics (Taylor has over 500 registrations internationally, the earliest dating back 17 years to 2007), reclaiming control of her masters through ‘TAYLOR’S VERSION’, she illustrates how effective IP management can drive long-term success in the competitive music industry while safeguarding her brand and ‘REPUTATION’ from unauthorised use. In the end, Taylor Swift’s relationship with IP has indeed turned out to be a ‘Love Story’.

Mathys & Squire Partner Nicholas Fox has been prominently featured in a recent article by the Solicitors Journal, which discusses the Unified Patent Court’s (UPC) decision to grant the firm access to crucial evidence in a patent dispute between Astellas and Healios. The article highlights Mathys & Squire’s significant role in challenging the court’s approach to transparency, as the firm sought access to documents that were initially restricted by the UPC.

In his comments, Nicholas Fox expressed mixed feelings about the court’s decision. On the one hand, he acknowledged the positive outcome of finally gaining access to the requested documents, which marks a step forward in promoting transparency within the newly established UPC system. He states that this victory reflects Mathys & Squire’s commitment to enhancing openness in the judicial process, particularly in the context of the UPC, which has only been operational for just over a year and is still refining its procedures. However, Fox also voiced serious concerns regarding how the UPC handled the access request.

He emphasised the considerable delay in processing the request, noting that it took more than eight months for the court to grant access which resulted in the case being settled shortly before the access request was finally granted.” This delay, according to Fox, undermined the value of the access granted, as it prevented third parties from monitoring the case in real-time.

To read the full article click here.

Mathys & Squire Managing Associate Harry Rowe was recently featured in ‘’Claiming X: lessons from the controversial rebrand that cost Twitter $3.2 billion in brand value ‘’ article by World Trademark Review (WTR) and provided commentary on how the company’s trademark protection strategy looks a year on.

Harry Rowe says: ’’…Trademark examiners at the EUIPO have, in recent years, adopted a stricter approach regarding the level of distinctiveness required for a trademark to be registrable…’’

This comment was first written for and published in WTR on 24 July 2024, to read the full article click here.

One of the first tasks of the new UK Minister for AI, Feryal Clark MP, should be to make it easier for companies to patent AI models in the UK says Andrew White, Partner, of Mathys & Squire the intellectual property law firm.

Andrew White says that reforming patent rules should be a key part of the Government’s efforts to attract more investment into the UK’s IT industry.

Detail on proposed legislation related to AI was dropped from last week’s King’s Speech. However, Andrew White says that introducing reforms to make the UK more welcoming to AI investment could ensure that the UK starts to catch up with other countries like France, China and the US that have taken more of a lead in AI.

Andrew explains that at present the UK’s rules on patenting AI technology are restrictive and complex and make it too difficult to patent AI inventions, in particular inventions relating to a new or improved AI model, such as Large Language Models.

In both the UK and other major economies, it is possible to patent a novel way of using AI to solve a problem, but it is often not possible to patent the AI itself (“core AI”), such as a new form of Large Language Model. AI-based inventions, and in particular those directed to “core AI”, are often excluded from being patented as being seen by the UK’s Intellectual Property Office as a “program for a computer” or a “mathematical model”.

A High Court case Emotional Perception AI vs UKIPO had offered a route for patenting Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), but the UK’s Intellectual Property Office has actually very recently successfully challenged that decision in the Court of Appeal, shutting down one of the few routes in the UK to patent an AI invention.

Adds Andrew: “The UK’s rules for patenting technology have developed over the last 30 plus years and are in need of a proper review to see that they are fit for purpose. Many IP lawyers think that the law over patenting fundamental AI technology in the UK has become antiquated.”

“Without a proper reform we can’t expect that the courts will adapt to help the UK take a lead in AI.”

“Allowing the patenting of a wider group of AI inventions would automatically create an advantage for the UK over other jurisdictions.”

The fates of three requests for access to pleadings and evidence filed with the Unified Patent Court (UPC) demonstrate how the judges of the UPC are still struggling with the court’s commitment to transparency and open justice.

Rule 262.1(b) of the UPC Rules of Procedure provides that: “written pleadings and evidence, lodged at the Court and recorded in the Registry, shall be available to the public upon reasoned request.” Although this would appear to demonstrate a strong commitment to transparent public justice, the speed with which access requests are being processed raises questions as to whether pleadings and evidence will ever be made available to the public in advance of a final decision on a matter.

Orders issued in the last few days by the Paris Section of the Central Division, the Local Division in The Hague, and the Munich Section of the Central Division illustrate these problems.

Success in Paris

The Paris Section of the Central Division of the UPC has granted Mathys & Squire access to the pleadings and evidence filed by the parties in the BITZER Electronics v Carrier Corporation dispute regarding the revocation of European patent number EP 3414708. The order granting access has not been published by the UPC but we have made a copy available here.

We filed our request while proceedings were ongoing, primarily because the evidence on the Court’s Case Management System (CMS) appeared to indicate that Carrier Corporation had lodged a request to opt EP 3414708 out of the jurisdiction of the UPC two weeks before BITZER Electronics filed their revocation action on 27 July 2023. This raised interesting questions. Was the Central Division hearing a revocation action on an apparently opted-out patent? Was there something about Carrier’s opt-out request which rendered it invalid? Would that error apply to other opt-out requests placing the validity of those opt-outs in doubt?

Adding to the mystery, an earlier order in the same case (which had denied access to a third party seeking certain other documents) referred to the opt-out request as an “intermediate opt-out”. The summary of facts in that order and the names of certain documents in the CMS suggested that the opt-out had been filed in between an earlier version of the revocation action which was deficient in some way, and a later version which had been corrected.

The actual answer was far more prosaic. Having been granted access to the pleadings filed with the Court, it is now apparent that the date when BITZER’s revocation action had been filed has been incorrectly recorded in the CMS. BITZER’s revocation action had in fact been filed on 28 June 2023 and corrected on 7 July 2023, both of these dates being before Carrier had applied to opt EP 3414708 out of the jurisdiction of the UPC and not after. The opt-out request had simply been filed too late. The origin of the incorrect dates in the CMS remains an enigma.

Our access request, which raised no objections from the parties to the underlying litigation, took 54 days or just under 2 months to process from filing on 5 June 2024 to a final decision on 29 July.

Meanwhile in The Hague

The day before the Paris Section granted Mathys & Squire instant access to the BITZER v Carrier pleadings, the Local Division in The Hague ruled on a request for access to pleadings in the pending dispute between Abbott Diabetes Care and Sibio Technology.

In that case, the Judge-Rapporteur granted a member of the public access to selected pleadings relating to an earlier Preliminary Injunction application in the pending Abbott v Sibio case. Such access was granted over objections raised by the parties to the underlying proceedings. Access was delayed for 15 days from the date of the order to give the parties the opportunity to appeal the decision.

The Hague Local Division processed the access request in the Abbott v Sibio case far faster than the Paris Section.

The request filed before the Local Division in The Hague was filed on 3 July 2024, meaning that The Hague Local Division has ruled on this request in 26 days, which included the time to provide the parties to the litigation the opportunity to comment on the request.

The wheels of justice

The relative speed with which the court decisions in The Hague and in Paris issued is in contrast with the speed, or rather lack thereof, with which the Munich Section of the Central Division is processing another access request that Mathys & Squire filed with the Court. That request, which is still pending, was filed over 8 months ago on 21 November 2023.

Although much of that delay was due to the Munich Section’s decision to stay the application pending the decision of the UPC Court of Appeal in Ocado v Autostore, compared with The Hague Local Division and Paris Section of the Central Division the processing of the request by the Munich Section since the Ocado decision appears positively glacial.

The UPC Court of Appeal issued its decision in Ocado v Autostore on 10 April 2024 and we provided our comments on the Ocado v Autostore appeal to the Court at the beginning of May. The Munich Section then set a deadline of 5 June for the parties to the litigation where we were requesting access to provide comments. Another 7 weeks would then pass before the Munich Section wrote to inform us that the parties had settled the litigation, asking whether this would cause us to withdraw our access request. We promptly responded to inform the court that it did not. However, access still has not been granted as the Court has provided the parties until mid-August to file yet further comments and request redaction of documents before issuing a ruling on our request.

Hence, despite the Munich Section having stated an intent that our access request would be processed “expeditiously” once the outcome of the Ocado v Autostore appeal was known, any substantive decision on the request will not be issued until more than 4 months after the outcome of the appeal was published, within which time the parties to the underlying action have settled their dispute.

How public is “public access”?

The Court’s handling of these requests raises questions about its commitment to open justice. Hearings before the Court are public and yet the Court of Appeal’s reasoning in Ocado suggests that access to the written pleadings forming the basis for those hearings may be restricted while proceedings are ongoing. While the Court left that question open to some extent, if this approach is followed it will leave the public in the unsatisfactory position of being able to attend oral hearings before the UPC, but not to know the details of the case in advance or to have access to documents which would help them to understand the arguments made at the hearing.

Our requests in the Paris and Munich Sections of the Central Division were filed during ongoing proceedings. However, the issuance of a decision concluding the BITZER Electronics v Carrier Corporation proceedings on the same day that we were granted access to the pleadings meant that the Paris Section did not have to address the questions left open by the Court of Appeal regarding access to pleadings during on-going litigation. Nor will the Munich Section have to address that question in their final ruling on the pending access request as the parties to that case settled their dispute during the lengthy time period the Munich Section has taken to process our application.

Although the processing of a request by The Hague Division in less than a month is encouraging, the longer timescales observed in other divisions of the UPC have effectively amounted to a de facto bar on public access to pleadings until after the conclusion of those cases without the Courts ever needing to make a formal ruling on this question.

However, even in The Hague, access to the pleadings prior to the conclusion of an underlying case is not certain as the decision of The Hague Local Division is still subject to the possibility of an appeal which, if filed, would further delay the release of the pleadings in that case. Nor will The Hague decision provide a third party with access to the written pleadings and evidence relating to the substantive dispute between Abbott and Sibio as the third party has limited their request to pleadings concerning the concluded preliminary injunction application in that case.

The chance to see whether the Court will ever grant access to the written pleadings and evidence forming the basis for a dispute pending before the court will have to wait for another day.

As we reported on in 2022, the UKIPO has been working with stakeholders to assist in the challenges faced by industry with respect to standards essential patents (SEPs). This work has resulted in the recent launch of the UKIPO’s “SEPs Resource Hub”.

As many readers will be aware, patents which protect a technology which are deemed essential to implementing a technical standard are known as SEPs. Such technical standards set out how devices interact with each other, such as cellular communication devices which operate in accordance with wireless communication standards (e.g. 3GPP). Use of these standards enable devices to seamlessly communicate with one another, wherever they are located in the world, as long as they are using (and hence implement) the same technical standards.

The SEPs Resource Hub (Hub) seeks to provide a one-stop repository of guidance and signposting for UK businesses as they interact with technical standards and standard setting organisations, enter negotiations in respect of SEPs, as well as matters relating to dispute resolution in the context of SEPs. Having such a Hub will assist businesses to better understand and traverse the often-complex world of SEPs.

The Hub also provides a very useful summary of UK SEPs Case Law, a glossary of SEP related terms, and international SEPs-specific resources. The IPO have noted that the Hub will continue to be updated and evolve over time.

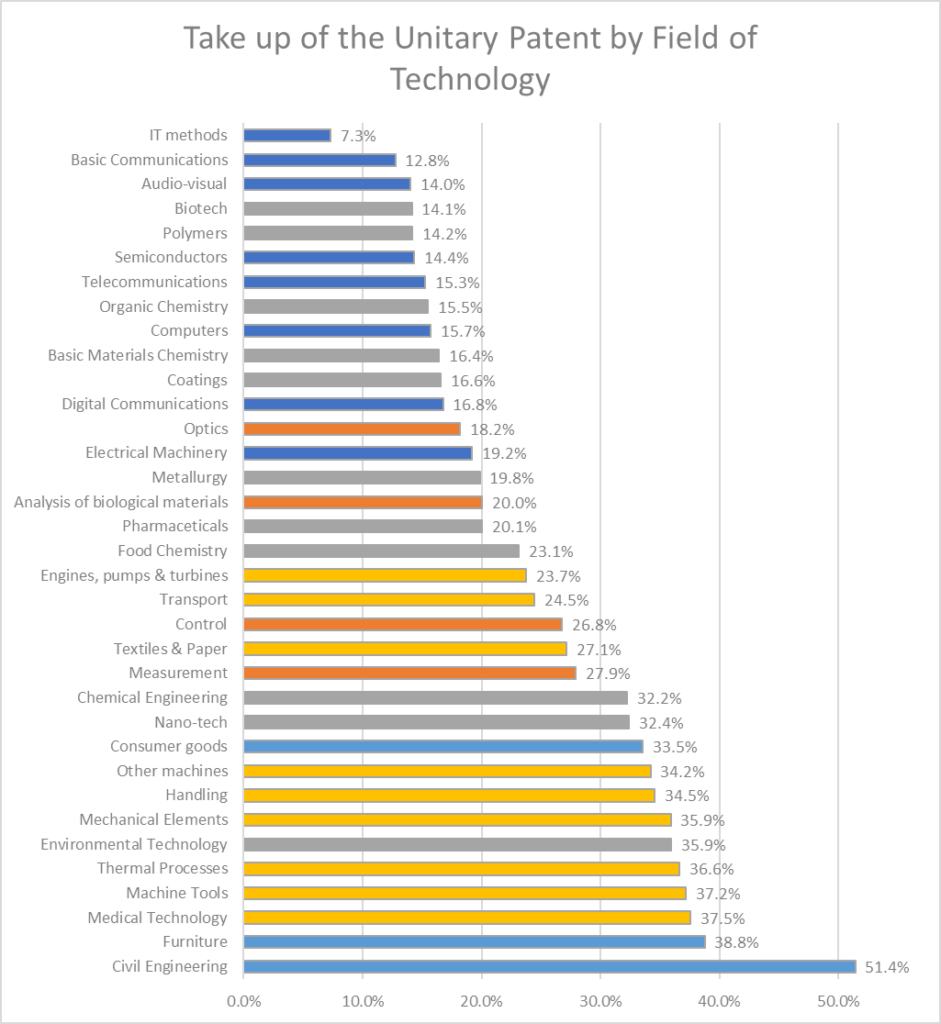

Since March, the rate at which European patents granted by the European Patent Office (EPO) are converted to Unitary Patents has risen from 18% to 24.3%, an increase of 35%. The figures provided by the EPO, indicate that this increase has occurred across all technologies, but the rate of increase has been far more significant in some technology areas than others, indicating that reluctance to use the Unitary patent system in such areas is declining.

The graph above illustrates the current rates of use of the Unitary patent in different technology areas. The different colours in the graph correspond to the EPO’s broad technology areas: Electricity (Dark Blue), Chemistry and Life Sciences (Grey), Instruments (Orange), Mechanical Engineering (Yellow) and Other Fields (Light Blue).

Compared with 4 months ago, the overall ordering of adoption of the Unitary patents in different technical fields is little changed. However, the proportion of patents being granted which have been converted to Unitary Patents has increased considerably.

Civil engineering and Furniture remain the areas of technology where Unitary patents are most popular. The increase in take-up in these fields from 40% to 51.4% in the case of Civil Engineering and from 30% to 38.8% amounts to increases of about 30% in both fields, only slightly behind the average 35% increase of take up Unitary Patents across the board.

More dramatic increases in uptake have occurred in other technical areas, in particular Semiconductors where the rate of uptake has nearly doubled from 7.3% in March to 14.4% in July.

Uptake has increased by 50% in Polymers (previously 9.2%, now 14.2%), Audio Visual (previously 9.2%, now 14%), and Computers (previously 9.8%, now 15.7%) where uptake was previously relatively low, as well as areas where uptake was already previously higher such as Thermal Processes (previously 24.5%, now 36.6%) and Medical Technology (previously 24.4%, now 37.5%).

A notable outlier in this more general increase in enthusiasm for the use of the Unitary patent is IT Methods, which remains the area of technology in which the uptake for Unitary patents remains the lowest at 7.3%. Although this is an increase on the 6.4% uptake rate previously reported in March, this change only amounts to an increase of 14%, less than half of the average of 35% across all technologies.

The significant increases in the use of the Unitary patent in the last few months indicates that many more companies are now choosing to convert at least some of their European patents into Unitary patents. This will ultimately lead to an increase in the numbers of patents which are subject to the jurisdiction of the Unified Patent Court as Unitary patents are always subject to the jurisdiction of the Court and cannot be opted-out from the jurisdiction.

However, it is also clear that in the majority of technical fields, at least for the time being, most patents will remain European patents.

On 19 July 2024, the Court of Appeal under Lord Justice Birss handed down its judgement on the case of Comptroller – General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks v Emotional Perception AI Limited [2024] EWCA Civ 825. The Court of Appeal judgement overturns the first instance decision of the High Court and upholds the decision of the UKIPO Hearing Officer.

The judgement held that:

- A computer is “a machine which processes information” (see reasons 61 and 68).

- A computer program is “a set of instructions for a computer to do something”, i.e. “to process information in a particular way” (see reasons 61).

- An artificial neural network (ANN), however it is implemented (in hardware or software), is a computer (see reasons 68).

- The weights and biases of an ANN, however it is implemented, are a computer program (see reasons 68 and 70)

- The sending of an improved recommendation is not a technical effect because its effect is subjective and cognitive in nature, not technical (see reasons 79 and 81). This is in line with the EPO’s approach.

- Emotional Perception’s invention is excluded for being a computer program as such (see reasons 83).

The full Court of Appeal decision can be found here.

In response to the issuance of the decision, the UKIPO has suspended its guidance on the examination of patent applications relating to artificial intelligence. It remains to be seen whether the UKIPO’s practice will now revert to that before the first instance decision was issued last November, whereby ANNs are treated no differently to any other form of computer implemented invention.