Mathys & Squire is proud to be ranked as a leading European patent firm by the Financial Times (FT) in their 2023 report.

The annual list is based on recommendations by clients and peers, as compiled by the FT’s research partner Statista. As well as being featured as a leading patent firm, Mathys & Squire has also been recognised in five specialist areas of industrial expertise this year: ‘Biotechnology, Food & Healthcare‘, ‘Chemistry & Pharmaceuticals‘, ‘Electrical Engineering & Physics’, ‘IT & Software‘, and ‘Mechanical Engineering.’

We would like to thank all our clients and contacts who have taken the time to recommended the firm as part of the FT’s research.

To access the full report and rankings tables, please visit the FT website here.

Bioinformatics is a rapidly growing field that combines biology, computer science, and statistics to analyse biological data. The field has become increasingly important in recent years due to the explosion of data generated by advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies.

The field has played a crucial role in advancing our understanding of genetics, genomics, and personalised medicine. However, there is a common misconception that many of the key aspects of these inventions are unpatentable such as features of genomic pipelines e.g clustering or aligning. There are of course, challenges to patenting bioinformatics methods but it can and is being done at an increasing rate.

Rise of bioinformatic-related patents

Patenting in the field of bioinformatics is not new. In fact, the first bioinformatics-related patent was filed in 1988. However, it was not until the early 2000s that the number of bioinformatics-related patents began to increase significantly. This initial increase was driven by the rapid advances in DNA sequencing technologies, which enabled researchers to generate vast amounts of genetic data. These advances led to the development of new bioinformatics tools and methods for analysing and interpreting this data.

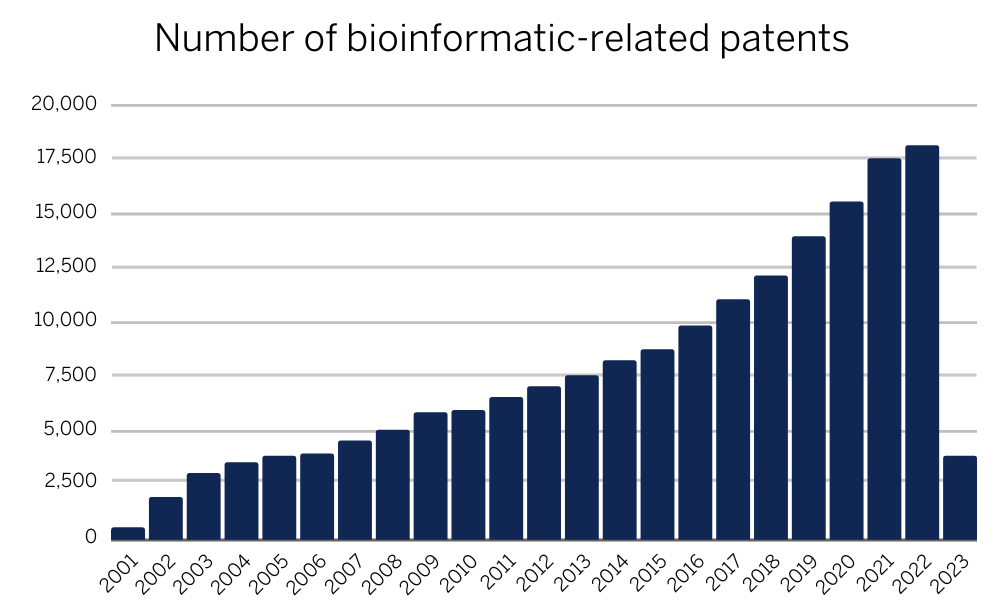

Figure 1: Increasing global trend of bioinformatics-related patents (data acquired from IP Quants)

In recent years, the number of bioinformatics-related patents has continued to increase. According to a report by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the number of bioinformatics-related patent applications increased by an average of 13.2% per year between 2013 and 2018 (Intellectual property protection indicators 2019). From data available since 2001, there has been a year-on-year increase in bioinformatics-related patents with a record-breaking number of patents filed in 2022 at just over 18,000 which is set to be broken again in 2023.

The increase in bioinformatics-related patents can be attributed to several factors.

- First, the growth of the biotechnology industry has led to increased investment in research and development. This has resulted in the development of new bioinformatics tools and methods for analysing biological data, which are often patented to protect intellectual property rights.

- Second, the availability of large datasets, such as those generated by the Human Genome Project, has made it possible to identify new targets for drug development and personalised medicine. These targets can be patented to protect the commercial rights of the companies that develop them.

- Finally, the increase in bioinformatics-related patents can also be attributed to advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning. These technologies are being used to analyse biological data and develop new algorithms for predicting disease risk, drug efficacy, and other important factors.

Growth in the bioinformatics market

The bioinformatics market is also a rapidly growing industry commercially, with a wide range of players offering products and services in the field. The global bioinformatics market in terms of revenue was estimated to be worth $10.1 billion in 2022 and is poised to reach $18.7 billion by 2027. Some of the major players in the bioinformatics market include:

- Illumina: Illumina is a leading provider of DNA sequencing and genotyping technologies. The company’s products are used in a variety of applications, including cancer research, infectious disease monitoring, and personalised medicine.

- Thermo Fisher Scientific: Thermo Fisher Scientific is a global provider of scientific and laboratory equipment, reagents, and services. The company offers a range of bioinformatics products, including software for genomic analysis, data management, and interpretation.

- Qiagen: Qiagen is a provider of sample and assay technologies for molecular diagnostics, applied testing, and academic research. The company offers a range of bioinformatics products, including software for genomic data analysis, interpretation, and visualisation.

To give an example, according to data acquired form IP Quants, Illumina Inc has over 470 patents relating to the bioinformatics field ranging from neural network-based pipeline to deep learning-based approaches, highlighting the diversity of technology available to patent within this field. These are just a few examples of the major players in the bioinformatics market. However, it is not only in industry where we have observed a rise in bioinformatics-related patents. There is a similar trend in academia. For example, the University of California has filed over 2000 patent application between 2002 and 2023, highlighting the academic interest in this field.

As the field continues to grow and evolve, new players are likely to emerge, offering innovative products and services to meet the growing demand for bioinformatics solutions.

Conclusions

The increase in bioinformatics-related patents reflects the growing importance of this field in advancing our understanding of genetics, genomics, and personalised medicine. As the field continues to evolve and expand, we can expect to see even more exciting developments and innovations in the future. It is important for researchers, industry professionals, and patent professionals to stay informed and engaged in this rapidly changing field.

A recent case at the European Patent Office (EPO) Boards of Appeal, T 1806/18, held a known drug dispersed in apple sauce and orally administered to treat its authorised condition could be inventive – despite such a formulation having been disclosed as being administered to healthy individuals in clinical trial documents.

Request

The Appellant-Proprietor appealed the decision of the Opposition Division (OD) to revoke the patent. Claim 1 of the main request read (in simplified form):

“A pyrimidylaminobenzamide of formula (I) … [the compound known as nilotinib] or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, for use in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), wherein the compound … is orally administered dispersed in apple sauce.”

Novelty

A key cited prior art document was a document from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) relating to a paediatric investigation plan (PIP) for nilotinib (document D1). D1 included three clinical study protocols: a first study in which the bioavailabilities of nilotinib capsules and dispersions in apple sauce or yoghurt were to be assessed in healthy adult volunteers, and second and third studies in which paediatric CML patients were to be administered nilotinib formulations (with no explicit mention of a dispersion in apple sauce). Whilst nilotinib was known to be effective at treating CML in adults, outcomes for none of the three trials were known by the priority date of the patent. Even though the studies were to include very young children who would not be able to swallow the capsule formulation, the Board held that “this fact does not allow concluding with certainty that this patient subset will receive the nilotinib/apple sauce formulation” (section 6.10 of the reasons), agreeing with the OD’s finding of novelty.

Inventive step

Of interest, the Board agreed with the Respondents-Opponents’ argument that the first study described in D1 was a suitable starting point for the assessment of inventive step, i.e., that this could be considered as a closest prior art disclosure despite the lack of results.

However, the Board disagreed with the Respondents’ argument that safety issues should not be considered when formulating the objective technical problem (OTP) to be solved because the reported safety issues were related to the specific use of apple sauce and not the distinguishing feature, i.e., the therapy. Instead, the Board approved of the Appellant’s reference to decision T 2506/12, which held that for a treatment to be effective, it must meet the criterion of efficacy and acceptable safety.

The Board then disagreed with the Respondents that the formulation was obvious based on D1 in light of the common general knowledge (CGK). The Board pointed to D6, that provided evidence that formulation with different foods altering the bioavailability of drugs in unpredictable ways was CGK. The Board also pointed to D58, which compared formulations of a different drug product in or with different foods, including in apple sauce, and showed there was differing drug bioavailability depending on the specific food type. D58 reports that the authors were surprised when small amounts of apple sauce caused significant delays in gastric emptying. The Board took this as further evidence of unpredictability and concluded the skilled person would not have been able to predict whether apple sauce would have any effect, and if so, how much, on the oral bioavailability of nilotinib. The Board also held that the skilled person would have been aware of other documents (e.g., D21) teaching that nilotinib can have potentially life-threatening adverse events when taken with food.

In reaching this conclusion, the Board made an interesting comment about the attitude of the skilled person when starting from D1. In particular, the Board agreed with the Respondents that “the skilled person would not have adopted a try-and-see attitude in solving the posed technical problem”, but went on to state that “this does not make the unpredictability of the food effect irrational. The fact that a clinical study is announced in a prior art disclosure does not automatically mean that its outcome was predictable and that a reasonable expectation of success had to be acknowledged.” (section 7.21 of the reasons).

The Board also dismissed the Respondents’ argument that the fact that the PIP applicant in D1 was the originator of the nilotinib capsule formulation would indicate that the applicant had a reasonable expectation of success with the claimed formulation (and that this could be inferred by the skilled person). Whilst the Board did not doubt the credibility of the content of D1, it stressed that “the respondents did not explain why the clinicians of the PIP applicant – despite being aware of the known unpredictability of the food effect of apple sauce on nilotinib – would still have had a reasonable expectation that the nilotinib/apple sauce formulation would exhibit an oral nilotinib bioavailability in healthy human adults comparable to that of the [commercial] capsule formulation” (section 7.52 of the reasons). The Board drew a distinction on the facts over decision T 239/16, which had been cited by the Respondents, on the basis that (i) the closest prior art in that case was a phase 2 clinical study; and (ii) there was no knowledge in the state of the art to diminish an expectation of success in the proposed treatment. By contrast, in the case at issue the closest prior art was a pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers, the result of which was unpredictable.

As there was no reasonable expectation of success based on D1 (or other documents) that the apple sauce formulation would have a comparable bioavailability to the capsule formulation, and hence be effective in treating CML, claim 1 was held inventive, overturning the OD’s decision.

Take home messages

This case further builds on established case law that the disclosure of planned clinical trials or clinical trials without published results do not mean the outcome of such trials is predictable, or that a reasonable expectation for success has to be acknowledged (see, for example, T 239/16). In this respect, it provides some comfort for patentees and innovators, although the Board does stress repeatedly that the correct approach will depend strongly on the facts of the case.

This particular case goes to show that even when a regulatory authority has approved a planned clinical trial in the intended patient group, a claim to the proposed treatment can still involve an inventive step. The case further illustrates how unpredictable effects of drug formulations can form the basis of a valid medical indication claim at the EPO.

Pride Month is a time to celebrate the accomplishments, resilience, and contributions of the LGBTQIA+ community. While progress has been made towards equality and acceptance, it is important to recognise the trailblazing innovators who have left an indelible mark on the world.

From groundbreaking scientific discoveries to transformative technological advancements, LGBTQIA+ individuals have played a crucial role in shaping our society. In this article, we at Mathys & Squire celebrate the achievements of some remarkable innovators and inventors who have inspired change and left an important legacy.

Alan Turing unleashed the power of computing

Alan Turing, a gay mathematician, logician, and computer scientist, is widely regarded as the father of modern computer science. His work during World War II in cracking the German enigma code was instrumental in the allied victory. Alan’s conceptualisation of the Turing machine laid the groundwork for modern computing and artificial intelligence. Despite his brilliance, Turing faced persecution due to his sexuality, reminding us of the profound impact discrimination can have on human potential.

Lynn Conway pioneered microelectronics

Lynn Conway, a transgender woman, is an esteemed computer scientist and electrical engineer known for her invaluable work in the field of microelectronics. Her innovative research on the very large scale integration chip design revolutionised computer architecture. Conway’s work has been instrumental in enabling the development of modern computers, smartphones, and other electronic devices. She is an advocate for transgender rights and has been an inspiration to countless aspiring engineers.

Martine Rothblatt pushed the boundaries in biotechnology

Martine Rothblatt, a transgender entrepreneur, lawyer, and author, has made significant contributions to the fields of biotechnology and healthcare. As the founder of United Therapeutics, Rothblatt focused on developing treatments for pulmonary hypertension. She also spearheaded advancements in xenotransplantation, the transplantation of organs between species, with a focus on utilising pig organs to address the organ shortage crisis. Rothblatt’s work exemplifies the potential for innovation when diverse perspectives are embraced.

Benjamin Barres revolutionised neuroscience

Dr. Benjamin Barres was a transgender neurobiologist, whose innovative work contributed to our understanding of the brain and its functions. His research focused on glial cells, which were once considered passive support cells but are now known to play a critical role in brain development and function. Barres’s work challenged prevailing dogmas and opened new avenues of exploration in neuroscience. He was an outspoken advocate for gender equality in academia and worked to address the underrepresentation of women and transgender individuals in science.

Chien-Shiung Wu transformed nuclear physics

Dr. Chien-Shiung Wu, a lesbian physicist, made groundbreaking contributions in the field of nuclear physics. Known as the ‘first lady of physics’, Wu played a pivotal role in disproving the law of conservation of parity, which had been considered a fundamental law of physics. Her experiments, including one known as the Wu experiment, provided evidence for the violation of parity symmetry in weak interactions. Wu’s work fundamentally reshaped our understanding of the fundamental forces of nature. Despite facing gender and racial discrimination during her career, she persevered and left an indelible mark on the field of physics.

Sarah McBride fighting for LGBTQIA+ rights

While not an inventor in the traditional sense, Sarah McBride, a transgender activist, is an innovator in the realm of LGBTQIA+ rights and political advocacy. As the first openly transgender person to speak at a major party convention in the United States, McBride has been a prominent voice for equality and inclusion. Her work focuses on advancing legislation to protect LGBTQIA+ individuals from discrimination, and she continues to inspire others with her advocacy and commitment to social justice.

Tim Cook revolutionising the technology landscape

Tim Cook is a prominent figure in the technology industry and the CEO of Apple Inc. He succeeded Steve Jobs and has been instrumental in shaping the company’s success. Cook, who is openly gay, has been a vocal advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights and workplace inclusion. Under Cook’s leadership, Apple has continued to innovate and introduce groundbreaking products, revolutionising the technology landscape. Cook’s emphasis on user-friendly design, sustainability, and privacy has garnered praise and contributed to Apple’s continued growth and influence. His strategic vision and commitment to excellence have solidified Apple’s position as one of the world’s leading technology companies.

As we celebrate Pride Month, it is essential to recognise the invaluable work of LGBTQIA+ innovators and inventors who have reshaped the world with their brilliance and courage. From Alan Turing’s pioneering work in computing to Lynn Conway’s transformative research in microelectronics, these individuals have left a legacy that extends far beyond their respective fields. Their achievements serve as a testament to the power of diversity, inclusivity, and the limitless potential of human ingenuity. Mathys & Squire continues to honour and support LGBTQIA+ innovators as we strive for a future where everyone can thrive and contribute their unique talents to building a better world.

Last month, Amazon released their Brand Protection Report for 2022. Claiming to have invested over $1.2 billion and devoting 15,000 personnel to their brand protection initiatives, we look at some of the statistics and measures highlighting Amazon’s ongoing efforts to scale intellectual property (IP) protection and tackle the problem of counterfeits.

Robust proactive controls

Reportedly scanning over eight billion listings daily, Amazon states that controls such as seller verification and continuous monitoring have reduced the number of ‘bad actor’ attempts to create new selling accounts by more than 50%, year on year.

This will be reassuring for brands knowing that these measures have meant that apparently 99% of listings are proactively removed when suspected of being fraudulent, infringing or counterfeit.

Powerful tools to protect brands

Launched in 2017, Amazon’s Brand Registry provides brands with various automated protections to ensure their IP rights are protected. Amazon reports that these measures have seen a reduction of over 35% in the number of infringement notices submitted by brands compared to 2021.

Amazon also collaborates with the United States Patent and Trademark Office, working to ensure fraudulent applications and registrations are not used to enrol in its Brand Registry. They report that the partnership to date has identified and blocked over 5,000 false or abusive brands from enrolling in the Brand Registry.

Patent holders can also benefit from the Amazon Patent Evaluation Express, which allows neutral evaluation of a potentially infringing product in less time than a traditional lawsuit.

Holding bad actors to account

Amazon’s global Counterfeit Crimes Unit has reportedly succeeded in removing over six million counterfeit products from the global supply chain, claiming more than 1,300 criminals have been pursued through litigation and criminal referrals.

Protecting and educating customers

Partnerships with bodies such as the US Chamber of Commerce and the International Trademark Association show Amazon’s continued commitment to limit the reach of counterfeit goods and educate consumers.

Many brand owners will be keen to register their trade marks on the Brand Registry. Depending on the territory in which the trade mark is protected, brand owners would require either a pending application or registration in order to utilise the Brand Registry.

The Mathys & Squire team is happy to assist clients in filing trade mark applications and obtaining trade mark registrations for this purpose.

Data and commentary provided by Mathys & Squire has featured in articles by Environment Journal and The Patent Lawyer providing an update on the decline in Green Channel patent applications.

An extended version of the press release is available below.

The number of Green Channel patent applications in the UK has fallen by 47% within the last year, decreasing from 313 applications in 2021* to 166 applications in 2022*, says intellectual property law firm Mathys & Squire.

The Intellectual Property Office’s Green Channel was introduced in 2009 to encourage the development of more environmentally friendly technology by providing a quicker route for the patenting of that technology. It allows inventors of eco-friendly products to bypass the years’ long wait and obtain patents two to three times faster than they otherwise would.

The decline in the number of Green Channel applications may be because the benefits offered by the scheme aren’t enough of an incentive for smaller companies.

Posy Drywood, Partner at Mathys & Squire says that a better way of encouraging the development and patenting of green technology would be for the UK Government to pay for fees due to the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) for green patents.

Patent applications submitted through the IPO’s current Green Channel are fast-tracked through the evaluation process. However, the sooner a patent is approved, the sooner patent fees are due.

The Green Channel’s accelerated processing means that applicants have less time to gather the necessary funds, which isn’t always ideal for small businesses that may struggle to pay. In this way, speeding up the patent process could discourage small businesses from using the Green Channel.

Posy Drywood adds: “If we want to see a substantial increase in green technology created by the UK, just speeding up the patent application process is not going to cut it. Small businesses need more than that to make using the Green Channel worthwhile. As green technology is so important to the growth of the UK economy, subsidising green patent applications should be considered.”

“While fast-tracking the application process is a benefit, it also speeds up the time in which applicants have to pay their patent fees. That may be a deterrent to small businesses, especially as we enter into a period of economic uncertainty.”

“In its current state, the Green Channel isn’t working as effectively as it could do to promote more green technology. A better way to encourage greater IP production is to make patenting those products more affordable.”

*Year-end December 31

Owners of retained EU plant variety rights (PVRs) need to take action by 1 January 2024 in order to maintain these rights.

As was widely reported at the time, Brexit affected the protection afforded by various types of community intellectual property, including community plant variety rights (CPVRs).

Applicants with pending CPVR applications have already had to take action to convert their applications into corresponding UK plant breeders’ rights (PBRs).

However, holders of granted CPVRs have not, to-date, needed to take any action, as all varieties granted a CPVR by the end of the Brexit transition period were automatically given protection via a corresponding right under UK legislation. These are referred to by the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) as ‘retained EU PVRs’, and will have the same duration of protection as that remaining for the granted CPVR.

This automatic creation of retained EU PVRs has generated a massive number of new entries (>30,000) in the UK’s Variety Tracking System (VTS) database that require significant administration and management by APHA.

To assist in the management of these retained EU PVRs, APHA has announced that holders of such rights will need to proactively confirm that they wish to retain these rights.

In particular, the holders of retained EU PVRs need to provide APHA with:

- confirmation that they are the correct holder of the retained EU PVR;

- an express indication of which of their retained EU PVRs are to be maintained or surrendered (this information can be provided by completing Annex 1, which has been compiled by APHA and lists all retained EU PVRs, and has been provided by APHA to all rights holders);

- an address for service in the UK or the name and address of an agent within the UK (provided via a completed Authorisation of Agent (PVS11) form); and

- any changes to the details of the rights holder should be recorded on a completed APHA Assignments of Rights form (PVS10), together with a copy of the Community Plant Variety Office register excerpt showing that the EU holder of the rights has changed.

Once this information has been provided to APHA, the VTS will generate a UK grant number for each retained EU PVR, and this will be published in the Seed Gazette.

APHA has indicated that this information should be provided by 1 January 2024. After this date, the controller may formally request a UK address for service or a UK agent. If the information is still not provided for a given retained EU PVR, APHA may terminate said right if satisfied that the holder of the rights has failed to comply with a request under regulation 6 of the Plant Breeders’ Rights (Amendment etc) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019.

In view of the large number of retained EU PVRs that need to be migrated to the VTS, APHA is strongly advising holders of retained EU PVRs to provide the requested information well in advance of 1 January 2024.

If you need any assistance regarding confirming maintenance of your retained EU PVRs, please contact the author, or your usual Mathys contact.

The UK Government has appointed seven high-profile science and technology leaders to the new Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) Startup Board. These non-executive directors include the likes of astronaut Tim Peake, McLaren founder Ron Dennis, Professor of natural sciences Jason Chin (Trinity College, Cambridge), and Shonnel Malani, Managing Partner at Advent International, who will serve as lead non-executive board member.

The DSIT was established in February with a mission to cement the UK’s position as a science and technology superpower by 2030. Since then, it has announced funding of hundreds of millions of pounds for innovation accelerators, continued research into the field of life sciences and the development of laboratories, and has published strategies for growth in the artificial intelligence, quantum, and wireless infrastructure sectors.

The newly appointed non-executive board members will provide strategic guidance and insight as the department focuses on driving economic growth, creating jobs, and improving the lives of citizens through science, technology, and innovation. They will serve for nine months on an initial startup board that will nurture DSIT through its first year of existence, before a permanent board is recruited in due course.

Science and technology Secretary Michelle Donelan expressed the government’s commitment to incorporating the best and brightest minds from the science and tech worlds at every level of decision making in the government. The success of the DSIT, according to Donelan, will play a crucial role in delivering long-term economic growth, which is a priority for the UK Government.

In response to his appointment to the board, astronaut Tim Peake said that “As a former test pilot and astronaut, who has taken part in more than 250 scientific experiments for the European Space Agency and international partners, I hope to bring a wealth of experience of how science, technology and innovation are critical to both learning and development.”

The appointment of these high-profile figures to the DSIT Startup Board demonstrates the UK Government’s determination to advance the country’s science and technology leadership and agenda. It is also an opportunity for the private and public sectors to collaborate on innovative areas that will transform lives and drive economic growth across the country.

The appointment of these non-executive directors brings a wealth of experience and expertise to the DSIT, furthering the department’s ability to achieve its goal of making the UK a science and technology superpower in the coming years.

The European Commission published their proposals for new regulations on standards essential patents (SEPs), compulsory licensing of patents in crisis situations, and revised legislation on supplementary protection certificates (SPCs). These proposals, implemented by the European Commission, will only directly affect the European Union (EU) and not the UK.

Proposed regulations on standards essential patents

Of all of these proposals, the proposed new regulation on SEPs is perhaps the most contentious, having been leaked on 24 March 2023. This was commented on widely in the press and among the global patent community, including in a letter by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI), a post by IP Europe, and a post on LinkedIn by Fabian Gonell, Chief Licensing Lawyer at Qualcomm, who went so far as to say that the “draft regulation would upend patent rights in Europe and have a host of unintended consequences.” By contrast, Apple (an implementer) has been very active in lobbying for the current version of the draft regulation. Commentators have noted that is because the draft regulation would be pro-licensee and anti-patentee, and might well encourage ‘hold-out’ behaviour where an unwilling licensee could delay enforcement.

The proposals include assigning to the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), which currently administers community trade marks and community designs but does not yet have any patent expertise, the task of building an SEP register and a procedure for determining FRAND rates for SEPs. This also includes the option for regular checks (instigated by either implementer or SEP owner) to determine whether a sample of up to 100 patents are indeed essential – although the results of this are not legally binding. However, ETSI noted in their letter that they already maintain their own database of essentiality declarations and also technical specifications. The proposed regulations also impose an obligation on bodies such as ETSI to provide certain information to EUIPO which would place a significant burden on them, in particular relating to known implementations of the standard, which ETSI have said even they do not have the tools or resources to comply with.

With regards to determining FRAND rates for SEPs, this can be initiated upon request by an implementer or SEP owner and is to be completed within nine months and facilitated by ‘conciliators’ which shall be chosen by the parties from a group proposed by the EUIPO. However, commentators have questioned whether any imposed FRAND rate determination by two ‘conciliators’ (and without appeals available) at the EUIPO, an institution that until now has never dealt with patents before, resulting in a non-binding result in a very short timeframe, would work in practice, as it will unlikely be respected in the market.

IP Europe noted that the proposed new regulation is damaging for:

- departing radically from existing precedent, without sufficient data;

- turning over management of SEPs to an agency with no previous experience with patents or standards;

- creating an unpredictable and unbalanced system which will further delay licence negotiations and royalty payments, potentially for many years;

- ignoring the EU’s commitments under the World Trade Organisation’s TRIPS Agreement and TBT Agreement, and the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights to defend patent rights; and

- imposing an artificial and premature cap on aggregate royalties for implementations of a standard with a process that is open to misuse.

Compulsory licensing

The Commission notes that the new rules foresee a new EU-wide compulsory licensing instrument that would complement EU crisis instruments, such as the Single Market Emergency Instrument, HERA regulations and the Chips Act. The Commission states that in light of the COVID-19 crisis, these new rules would further enhance the EU’s resilience to crises, by ensuring access to key patented products and technologies, should voluntary agreements not be available or adequate.

Supplementary protection certificates

The proposal also introduces a unitary SPC to complement the Unitary Patent, along with a centralised examination procedure to be implemented by the EUIPO.

2023 EU SME fund

Concurrently with the proposal, the 2023 SME fund was also announced making vouchers available for SMEs to save up to €1,500 on their patent registration costs.

The European Commission’s proposals for new regulations on SEPs, compulsory licensing of patents in crisis situations, and revised legislation on SPCs have stirred up a lot of debate and commentary within the global patent community. While some, such as Apple, have actively lobbied for the proposed changes, others have expressed concerns about the potential unintended consequences of the regulations, particularly the new regulation on SEPs.

Nevertheless, the Commission argues that these new rules would boost innovation and investment within the EU, enhance the region’s resilience to crises, and support SMEs through the 2023 SME fund. It remains to be seen how these proposed regulations will be received and implemented within the EU and beyond.

The dispute began in 2022 when Lidl launched proceedings against Tesco, alleging that Tesco’s use of its ‘Clubcard Prices’ sign (Fig. 1 – yellow circle in a blue square with the words “Clubcard Prices” in the middle) amounted to trade mark and copyright infringement of its own Lidl mark (Fig. 1 – yellow circle, surrounded by a red ring in a blue square containing the word “Lidl” ) as well as its registration for the same design but without any text (the wordless mark).

Both marks comprise a yellow circle on a blue square, used by Tesco since September 2020 to advertise its Clubcard Prices loyalty discount scheme and indicate which products are eligible, and by Lidl in its main logo.

Lidl alleged that Tesco’s use of the yellow circle against a blue square was intended to deliberately take advantage of Lidl’s reputation as a discount supermarket and that consumers are likely to believe that Tesco’s mark is Lidl’s. Essentially, Tesco is “seeking deliberately to ride on the coat tails of Lidl’s reputation as a ‘discounter’ supermarket known for the provision of value.”

Tesco filed a counterclaim, arguing that:

- Lidl has never made genuine use if its wordless mark and that the registration should be revoked or declared invalid based on non-use.

- Lidl’s application to register the mark was filed in bad faith.

Drawing on arguments from Sky v SkyKick, Tesco alleged that the wordless mark was registered by Lidl as a legal weapon, a product of its trade mark filing strategy. There was, Tesco claimed, no intention by Lidl to use the mark in commerce, only to widen its legal monopoly right.

Tesco also accused Lidl of ‘evergreening’ by filing successive trade mark applications periodically for the wordless mark in 2002, 2005, 2007 and 2021 in order to refresh the grace period and avoid having to prove genuine use, drawing arguments from Hasbro Inc v EUIPO.

Lidl made an interim application to the Court to strike out Tesco’s counterclaim that some of Lidl’s registrations should be invalidated for bad faith and for permission to rely at trial on survey evidence in relation to the distinctiveness of its trade marks. The High Court agreed with Lidl on both counts and claimed that Tesco had not produced sufficient evidence to rebut the presumption that Lidl’s application had been made in good faith. The court held that mere lack of intention to use the trade mark did not constitute bad faith and struck out Tesco’s bad faith counterclaims. Tesco appealed.

Tesco’s grounds of appeal

Tesco argued that the High Court had:

- Failed to apply the correct test to the striking out application under rule 3.4(2)(a) of the Civil Procedure Rules, and that it had also failed to consider that bad faith is a developing area of the law.

- Failed to consider all of the alleged facts and inferences in its bad faith counterclaims in the context of Lidl’s infringement case, considering that no disclosure had yet been given by Lidl as to its intentions when registering the wordless mark.

On this premise, the Court of Appeal granted the appeal.

Court of Appeal decision

While disagreeing with Tesco’s argument that the judge had applied the incorrect test, the Court of Appeal did agree that Smith J had neglected to consider bad faith as growing field of law and failed to properly consider the pleaded facts.

Tesco’s first claim alleged that the wordless mark (first registered in 1995) was applied for without any intention of using the mark, but instead as a way of securing a wider legal monopoly than afforded by the mark used by Lidl since 1987 and registered in 2011 as a mark with text. The Court relied on Ferrero SpA’s Trade Marks [2004] RPC 29 and Target Ventures Group Ltd v EUIPO case T-273/19. In both cases, the proprietors’ registrations of new marks, which were not intended to be used in the course of trade but instead designed solely to extend the scope of existing registrations amounted to bad faith. The Court of Appeal held that it was wrong for the High Court judge to say that Tesco’s allegations were “no more than assertion”, as all allegations must be assumed to be true unless shown to be manifestly unsustainable. Lidl could have presented evidence to show that this allegation was unsustainable but had not done so.

On Tesco’s second claim that the re-filing of the wordless mark amounted to ‘evergreening’ and should be declared invalid, it relied upon Hasbro Inc v EUIPO Case T-663/19, in which the General Court found that Hasbro had acted in bad faith by re-filing its ‘MONOPOLY’ mark to avoid having to provide proof of use. Tesco alleged that Lidl’s re-filing activity supported the bad faith claim.

The Court of Appeal reversed the High Court’s decision to strike out Tesco’s bad faith counterclaims and held that Tesco had raised “sufficient objective indicia to give rise to a real prospect of the presumption of good faith being overcome so as to shift the evidential burden to the applicant for registration to explain its intentions.” Tesco had substantiated its pleadings sufficiently.

Where are we now: back in the High Court and going round in circles

In addition to providing a reminder of the legislative and judicial context for the concept of bad faith, the Court of Appeal’s decision provides useful insight into two specific types of activity that may result in a finding of bad faith: filing for ‘defensive’ marks and ‘evergreening’ marks, as well as highlighting that the concept of bad faith is a developing area of UK law.

We return full circle and on 7 February, the trial began at the High Court which will now reconsider Lidl’s initial claims of trade mark infringement and Tesco’s counterclaims of non-use and bad faith. The case will provide further guidance on various issues, such as the threshold needed to be met in satisfying the bad faith criteria, the process of ‘evergreening’, and what is meant by lack of intention to use a mark. We may also expect guidance on the use of wordless marks as well as the relevance of survey evidence in establishing the distinctiveness of trade marks.

Given the highly anticipated Sky v SkyKick appeal to the Supreme Court in June this year, which will further investigate the notion of bad faith, we can expect to see additional clarity in this area of law and an opportunity to define the rules.

Just like its own mark, Lidl seems to be going round in circles; a discount retailer, well known for invoking recognised supermarket brands with its lookalikes, is now ironically claiming that consumers will think of Lidl when using their Tesco Clubcard. In the meantime, we will keep an eye on both cases as we anticipate the judgements.